Alexander Hamilton

| Alexander Hamilton |

|---|

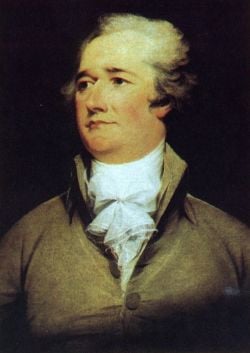

A portrait of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull, 1792

|

| Born |

| January 11, 1755 Nevis, British West Indies |

| Died |

| July 12, 1804 New York City, New York, United States |

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757 – July 12, 1804) was an American politician, statesman, writer, lawyer, and soldier. One of the United States' most prominent and brilliant early constitutional lawyers, he was an influential delegate to the United States Constitutional Convention and one of the principal authors of the Federalist Papers, which expounded and urged the ratification of the U.S. Constitution to skeptical New Yorkers. The Federalist Papers—and Hamilton's contributions to them—remain today a standard source on the original intent of the document.

Hamilton put the new United States of America onto a sound economic footing as its first and most influential Secretary of the Treasury, establishing the foundations for American capitalism, including the First Bank of the United States, public credit, and stock and commodity exchanges. To promote his national vision and defend against the differing political visions of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, Hamilton led efforts to found the first political party in the United States, the Federalist Party, which he dominated until his death. Despite charges by political opponents that he despised the masses and was a monarchist at heart, he was, in fact, deeply committed to the republican principles of the young constitutional republic.

Hamilton's nationalist vision was rejected in the Jeffersonian triumph of 1800, but Presidents James Madison and James Monroe would emulate many of his programs as they too set up a national bank, tariffs, internal improvements, and an army and navy. The later Whig and Republican parties adopted many of Hamilton's themes but never recognized him as a direct inspiration until about 1900.

Historians regard Hamilton as the Founding Father who advocated for the principles of a strong centralized federal government and loose interpretation of the Constitution's various provisions. He supported a strong national defense, aid to and protection of infant industries, solid national finances based on debt that linked the national government to the wealthy men across the country, and strong banks. His Report on Manufactures envisioned an industrial nation in what was then a rural agricultural country.

Although he was a devoted husband and father, Hamilton was politically tainted by entrapment in a sexual scandal. Throughout his meteoric political career, he both suffered and dispensed vitriolic abuse, ultimately leading to his death in a duel at the hands of his long-time political nemesis, Vice President Aaron Burr, in Weehawken, New Jersey, in 1804.

Early years

Alexander Hamilton was born illegitimately in the West Indies island of Nevis to James Hamilton, a businessman from Scotland, and Rachel Fawcett Lavien of French Huguenot descent, who was then married to another man. (The couple lived apart from one another under an order of legal separation. Re-marriage was forbidden by law at the time.) There is some uncertainty as to the year of Hamilton's birth. Throughout his life, Hamilton stated that it was 1757, and that year went unquestioned for centuries. More recent examinations of probate court records at St. Croix indicate the year was 1755 (though the year is not explicitly noted) and for several decades it has been the more commonly cited year. According to Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow, Hamilton may have misrepresented his age upon entering King's College (now Columbia College) because he was relatively old for a university freshman, which may explain the discrepancy between the court records and Hamilton's own statements about his birth year. The day, January 11, can be neither substantiated nor refuted, and is still commonly accepted.

Hamilton was always sensitive to the fact that, under the laws of the time, he was born illegitimate. Hamilton's childhood was Dickensian. His father abandoned him—with considerable emotional brutality, even for the times—in the course of jettisoning Hamilton's mother. Business misfortunes having caused his father's bankruptcy, and his mother having died suddenly of a fever in 1768, young Hamilton was thrown upon the care of maternal relatives at St. Croix, where he entered the counting house of Nicholas Cruger to work as a clerk. Shortly thereafter, Cruger, going abroad, left the boy in charge of the business. Improbably, Hamilton made a success of it, with the business being his first real education. He gained, in the course of it, an ease dealing with, and even commanding, men much older than himself; and French, an accomplishment common enough in the Antilles, but very rare in the continental colonies, and very useful in his later life to George Washington's staff.

He also, Chernow argues, came by his lifelong hatred of slavery there. His Caribbean home kept an enormous slave population down by iron laws and exemplary acts of terror, which confronted Hamilton with slavery on a daily basis. That knowledge, not materialism, underlay his later barely-veiled contempt for the supposedly idealistic agrarian theories of the Jeffersonians. Hamilton knew that their ideal society was built on the very real backs of black slaves. He rightly saw modernity and capitalism dooming that system.

As a teenager, Hamilton wrote a letter, published in a local paper, about a hurricane that had severely battered the West Indies. The letter was so dramatically written that it caused a sensation amongst the townspeople. They soon raised enough money to fund his passage to New York for an education. After six months in Elizabeth, New Jersey, he settled in New York City in 1772, and began grammar school. Later, he attended King's College, originally studying anatomy with the intent of becoming a doctor.

Revolutionary War

During this time, anti-British sentiment was growing in the American colonies. A visit to Boston seems to have thoroughly confirmed the conclusion, to which reason had already led him, that he should cast in his fortunes with the colonists. And Hamilton threw himself into their cause with ardor. In 1774-1775, he wrote two influential anonymous pamphlets that were attributed to John Jay; they show remarkable maturity ability, and rank highly amongst the political arguments of the time. To support the colonists, he organized fellow King's College students into a kind of artillery company, was awarded its captaincy on examination, and won the interest of Nathanael Greene and George Washington by the proficiency and bravery he displayed in the campaign of 1776 around New York City. He and his King's College compatriots briefly, but seriously, engaged the British in one of the earliest shooting confrontations of the American Revolutionary War.

Hamilton joined Washington's staff in March 1777 with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, and served for four years as his private secretary and confidential aide. The important duties with which he was entrusted attest Washington's entire confidence in his abilities and character, then and afterward. Indeed, reciprocal confidence and respect took the place of personal attachment in their relations.

But Hamilton was ambitious for military glory. It was an ambition he never lost. He became impatient of detention in what he regarded as a position of unpleasant dependence, and (February 1781) he seized a slight reprimand administered by Washington as an excuse for abandoning his staff position. But, later, he secured a field command through Washington and won laurels at Yorktown; there, Hamilton led an infantry regiment that assaulted and captured Redoubt Number 10 of the British fortifications in the siege of Yorktown.

Political career

After the war, he served as a member of the Congress of the Confederation from 1782 to 1783, and then retired to open his own law office in New York City. He founded the Bank of New York, now the oldest ongoing banking organization in the United States, in 1784. His public career resumed when he attended the Annapolis Convention as a delegate in 1786, and drafted its resolution for a Constitutional Convention.

He also served in the New York State Legislature and attended the U.S. Constitutional Convention in 1787. Throughout the convention's proceedings, Hamilton argued consistently for a strong central government, including a king-like president (minus the familial inheritance of power), and an upper legislative body based on the English House of Lords. For this, he was long derided by political foes as a monarchist. Hamilton opposed equal representation in the proposed Senate, saying that the concept "shocks too much the ideas of justice and every human feeling." He also wanted senators to serve for life, subject to good behavior. Finally, Hamilton strongly advocated the abolition of slavery.

Federalist Papers

Although the U.S. Constitution that the convention eventually produced was much less oligarchic than Hamilton had proposed, and the tenures of those exercising power were shorter than he desired, he was active in the successful campaign for its ratification in New York. He made the largest single contribution to the authorship of the Federalist Papers (writing 51 of the 85 that were published), which were extremely influential in that state and others during the debates over ratification, and are still often cited as examples of the Founders' rationale in writing the Constitution as they did.

Secretary of the Treasury

On the advice of a merchant named Robert Morris, with whom he had discussed economics as an aide-de-camp during the American Revolutionary War, President George Washington appointed Hamilton as the first Secretary of the Treasury when the first Congress passed an act establishing the Treasury Department. Hamilton served in that post from September 11, 1789 until January 31, 1795. It is for his tenure as Treasury secretary that Hamilton is considered one of America's greatest early statesmen.

Hamilton's term was marked by innovation, planning and masterful reports. In office for barely a month, he proposed the creation of a seagoing branch of the military to discourage smuggling and enhance tax collections. The following summer, Congress authorized a Revenue Marine force of ten cutters, the precursor to the United States Coast Guard. He also played a crucial role in creating the United States Navy (through the Naval Act of 1794). Hamilton's perceptive and creative mind, coupled with a driving ambition to set his ideas in motion, resulted in many proposals to Congress. His proposals included a plan for import duties (tariffs) and excise taxes for raising revenue and encouraging American manufacturing and for funding the Revolutionary War debt, which included debts owed by the states. He also developed plans for a congressional charter for the First Bank of the United States.

In 1790, Hamilton put forth a plan to deal with the immense national debt (which consisted of foreign, domestic and state debts), proposing to pay off all foreign debt to help restore national credit, which would then enable the nation to issue bonds to pay off the domestic debt. He reasoned that this would help ensure that the "aristocracy of wealth and talent" had a stake in the success of the new government. His plan was for the federal government to assume the individual states' debts, which would stabilize the country and ensure their loyalty to the union. It would work because creditors need the federal government to thrive in order to be paid.

Hamilton also asked for a whiskey tax and a high import tariff to help pay for the debt and increase domestic manufacturing (Report on Manufactures). Congress gave him the whiskey tax and the tariff but at a rate lower than he had wished. Finally, Hamilton asked for the creation of a national bank (First Bank of the United States) to help the government fulfill its financial obligations and create some income due to interest on loans and power to create a national currency through issuance of public credit. Hamilton's economic plan is significant not only for its restoration of the nation's credit and its attempt to deal with the United States' financial difficulties and dependence on the British Empire for manufactured goods, but also because it resulted in the first national political parties.

Contrary to popular belief, Hamilton did not believe in perpetual debt. He thought it was a weakness that should be avoided except under exceptional circumstances. He had set up a sinking fund that would have paid off all government debt, and wrote numerous articles denouncing perpetual government debt. [1] [2] [3][4]

He published the Report on the Public Credit[5] in January 1790. It was a milestone in American financial history, marking the end of an era of slipshod finance and debt repudiation which had virtually ruined American credit. The secret of British economic superiority and stable government, Hamilton argued, was its successful handling of debt.

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson strongly opposed all of Hamilton's financial plans, arguing that a bank was unconstitutional, that the original debt holders often sold their certificates and the new owners—who mostly lived in the North—were not really worthy enough. Hamilton argued that the rich and powerful men of every state who held the state debt certificates would give their loyalty to the national government, and without that loyalty the new nation would risk not having enough credit to fight a future war. After six months of rancorous debate, Hamilton, Jefferson and Madison met and worked out the Compromise of 1790.[6] The national capital would move from New York City to Philadelphia for ten years, and then permanently to what would later be called Washington, D.C. (District of Columbia), and both the funding of the Confederation debt and the assumption of the states' debts would pass Congress. Furthermore, the Northern anti-slavery forces would allow the removal of the capital to a slave state.

During Hamilton's tenure as Secretary of the Treasury, strong opposition to taxing liquor led to the Whiskey Rebellion in Western Pennsylvania and Virginia in 1794. Hamilton felt compliance with the laws was important, so he accompanied President Washington, General "Light Horse" Harry Lee and federal troops to help put down the insurrection, virtually without bloodshed.

Hamilton as an industrialist

Hamilton was among the first to recognize the larger transformations of industry and capitalism of his era, in particular the trend toward larger-scale manufacturing financed through credit. In 1778, he visited the Great Falls of the Passaic River in northern New Jersey and saw that the falls could one day be harnessed to provide power for a manufacturing center on the site. As Secretary of the Treasury, he put this plan into motion, helping to found the Society for the Establishment of Useful Manufactures, a private corporation that would use the power of the falls to operate mills. Although the company did not succeed in its original purpose, it leased the land around the falls to other mill ventures and continued to operate for over a century and a half.

Alexander Hamilton's support for protective import tariffs solidifies him as an important early supporter of protectionist trade policies. He preceded Friedrich List in this field being the advocate of traditional infant industry argument according to which industry should be protected from foreign competition so that it can survive until it becomes internationally competitive.

Out of the Cabinet

Hamilton's resignation as Secretary of the Treasury in 1795 as a result of an extramarital affair did not remove him from public life. With the resumption of his law practice, he remained close to Washington as an adviser and friend. Hamilton influenced Washington in the composition of his Farewell Address, and Washington often consulted with him, as did members of his Cabinet. Relations between Hamilton and Washington's successor, John Adams, however, were frequently strained. Adams resented Hamilton's influence with Washington, and considered him overambitious and scandalous in his private life; Hamilton compared Adams unfavorably with Washington, and thought him erratic and fussy. During the Quasi-War of 1798-1800, and with Washington's strong endorsement, Adams very reluctantly appointed Hamilton a Major General of the Army.

Adams had also held it right to retain Washington's cabinet, except for cause; he found, in 1800, that they were answering to Hamilton, rather than himself, and fired several of them. Hamilton also wrote a pamphlet which was highly critical of Adams (although it closed with a tepid endorsement) which badly hurt Adams' 1800 re-election campaign and split the Federalist Party, contributing to the victory of the Democratic-Republican Party, led by Jefferson, in the election of 1800.

Although Jefferson had beaten Adams, both he and his nominal running mate, Aaron Burr, received 73 votes in the Electoral College. At the time, electors did not cast distinct ballots for a President and Vice President, but rather each had two votes, with the highest vote-getter becoming President, and the second-place finisher becoming Vice President. (In large part as a result of this election, the Twelfth Amendment was proposed and ratified, adopting the method under which presidential elections are held today.) With Jefferson and Burr tied, the United States House of Representatives had to choose between the two men. Several Federalists who opposed Jefferson supported Burr, but Hamilton reluctantly threw his weight behind Jefferson, causing one Federalist congressman to abstain from voting after 36 tied ballots. This ensured that Jefferson was elected president rather than Burr. Even though Hamilton did not like Jefferson and disagreed with him on many issues, he was quoted as saying, "At least Jefferson was honest." Burr then became vice president. When it became clear that he would not be asked to run again with Jefferson, Burr sought the New York governorship in 1804, but was badly defeated.

Duel with Aaron Burr

Soon after the election, a newspaper referred to a "despicable opinion" attributed to Hamilton about Burr. This probably resulted from comments Hamilton made in private, sarcastically questioning Burr's integrity. Sensing a chance to regain political honor, Burr demanded an apology. Hamilton refused on the grounds that he could not recall the instance.

After an exchange of testy letters, and despite the attempts of mutual friends to avert a confrontation, a duel was nevertheless scheduled for July 11, 1804 along the bank of the Hudson River beneath a rocky ledge in Weehawken, New Jersey.

At dawn, the duel began, and Vice President Aaron Burr shot Hamilton. Hamilton's shot was fired into the air away from his opponent. A letter that he wrote the night before the duel state: "I have resolved, if our interview [duel] is conducted in the usual manner, and it pleases God to give me the opportunity, to reserve and throw away my first fire, and I have thoughts even of reserving my second fire." The circumstances of the duel, and Hamilton's actual intentions, are still disputed; the guns were obtained by Hamilton, they have survived, and they have a hair-trigger setting that may be switched on or off.

After considerable suffering, Hamilton died the next day and was buried in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery in Manhattan (Hamilton was Episcopalian). Governor Robert Morris, a political ally of Hamiltons, gave the eulogy at his funeral and secretly established a fund to support his widow and children; Hamilton's oldest son, Philip, had previously been killed in a duel in Weehawken in 1801, defending his father's honor.

Personal life

In spring 1779, Hamilton asked his friend John Laurens to find him a wife in South Carolina:

"She must be young—handsome (I lay most stress upon a good shape) Sensible (a little learning will do)—well bred…chaste and tender (I am an enthusiast in my notions of fidelity and fondness) of some good nature—a great deal of generosity (she must neither love money nor scolding, for I dislike equally a termagant and an economist)—In politics, I am indifferent what side she may be of—I think I have arguments that will safely convert her to mine—As to religion a moderate stock will satisfy me—She must believe in God and hate a saint. But as to fortune, the larger stock of that the better."[7]

Hamilton however found his own bride—one who matched his specifications. On December 14, 1780, he married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of Gen. Philip Schuyler, and thus joined one of the richest and most political families in the state of New York.

Affair

In 1794, Hamilton became intimately involved in an extramarital affair with a woman named Maria Reynolds that badly damaged his reputation and prevented him from rising further in politics. Reynolds's husband, James, blackmailed Hamilton for money, though he was content to permit sexual liaisons between Hamilton and his wife. When James Reynolds was arrested for counterfeiting, he contacted several prominent Jeffersonian Republicans, most notably James Monroe. When they visited Hamilton with their suspicions of malfeasance, he insisted he was innocent of any misconduct in public office, while admitting to an affair with Maria Reynolds.

Monroe promised to keep details from public knowledge, but Thomas Jefferson had no such compunctions. When rumors began to spread, Hamilton was forced to publish a confession of his affair, which shocked his family and supporters. A duel with Monroe over his supposed breach of confidentiality was averted by then-Senator Aaron Burr. Ironically, Burr would later represent Maria Reynolds in her divorce lawsuit, leading some to suspect he set Hamilton up. However, Hamilton's relationship with Burr had long been cordial during their years together as prominent New York trial lawyers.

Hamilton's widow Elizabeth (known as Eliza or Betsy) survived him for 50 years, until 1854; Hamilton had referred to her as "best of wives and best of women." Despite the Reynolds affair, Alexander and Eliza were very close and as a widow she always strove to guard his reputation and enhance his standing in American history.

Legacy

From the start, Hamilton set a precedent as a Cabinet member by dreaming up federal programs, writing them in the form of reports, pushing for their approval by appearing in person to argue them on the floor of Congress, and then implementing them. Hamilton did this brilliantly and forcefully, setting a high standard for administrative competence.

Another of Hamilton's legacies is his strongly pro-federal interpretation of the U.S. Constitution. Although the Constitution was drafted in a way that was somewhat ambiguous as to the balance of power between federal and state governments, Hamilton consistently took the side of greater federal power at the expense of states.

As Secretary of the Treasury, he established—against the intense opposition of Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson—the country's first national bank. Hamilton justified the creation of this bank, and other robust federal powers, on Congress' constitutional powers to issue currency, to regulate interstate commerce, and anything else that would be "necessary and proper." Jefferson, on the other hand, took a stricter view of the Constitution: parsing the text carefully, he found no specific authorization for a national bank. This controversy was eventually settled by the Supreme Court of the United States in McCulloch v. Maryland, which in essence adopted Hamilton's view, granting the federal government broad freedom to select the best means to execute its constitutionally enumerated powers, specifically the doctrine of implied powers.

Hamilton’s portrait began to appear during the Civil War on the $2, $5, $10, and $50 notes. His face continues to grace the front of the ten dollar bill, but after the death of Ronald Reagan, some suggested replacing Hamilton with Reagan; Hamilton has, however, survived. Hamilton also appears on the $500 Series EE Savings Bond.

Hamilton's upper Manhattan home is preserved as Hamilton Grange National Memorial.

Hamilton College and Columbia College

Alexander Hamilton served as one of the first trustees of the Hamilton-Oneida Academy when Samuel Kirkland opened the missionary school in 1793. When the academy received a college charter in 1812 the school was formally named Hamilton College. There is a prominent statue of Alexander Hamilton in front of the school's chapel (commonly referred to as the "Al-Ham" statue) and the Burke Library] has an extensive collection of Hamilton's personal documents. Additionally, the college is in possession of a number of Hamilton's personal artifacts which are periodically exhibited as a part of the college collection.

Columbia College, Hamilton's alma mater, whose students formed his makeshift artillery company and fired some of the first shots against the British, has many official memorials to Hamilton. The College's main classroom building for the humanities is Hamilton Hall, and a large statue of Hamilton stands in front of it. In a sense Hamilton himself was indirectly responsible for the former King's College patriotically renaming itself Columbia College after the Revolution. Hamilton, in a famous episode which Chernow confirms, helped a student mob chase the school's Tory headmaster out a window, and onto a boat back to England.

Writings

- Federalist Papers under the shared pseudonym "Publius" by Alexander Hamilton (c. 52 articles), James Madison (28 articles) and John Jay (five articles)

- Hamilton: Writings by Alexander Hamilton (2001, ISBN 1931082049)

- Report on Manufactures, his economic program for the United States.

- Report on Public Credit, his financial program for the United States.

Notes

- ↑ Harold C. Syrett, (ed.)The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 27 vols., (NY: Columbia University Press, 6: 98-106)

- ↑ Report on Public Debt, (January 1790)

- ↑ Harold C. Syrett, (ed.)The Papers of Alexander Hamilton. 27 vols., (NY: Columbia University Press, 12: 570)

- ↑ National Gazette, Philadelphia:(October 16, 1792).

- ↑ Full text of the Report on the Public Credit. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ First Federal Congress Project.The Compromise of 1790.gwu.edu. Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- ↑ Broadus Mitchell. Alexander Hamilton. (NY: Macmillan, 1957-1962. 1, 199)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Secondary sources

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. Jay's Treaty. New York: Macmillan, 1923.

- Brookhiser, Richard. Alexander Hamilton, American. NY: Free Press, 1999. ISBN 0684839199

- Chernow, Ron. Alexander Hamilton, NY: Penguin Books, 2004. ISBN 1594200092

- Elkins, Stanley M. and Eric McKitrick. The Age of Federalism: the Early Public Years 1788–1800. NY: Oxford University Press, 1994. ISBN 0195068904 (scholarly history of the 1790s)

- Ellis, Joseph J. Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002. ISBN 0375405445 (won Pulitzer Prize)

- Flexner, James Thomas. The Young Hamilton: A Biography. NY: Fordham University Press, 1997. ISBN 0823217906

- Fleming, Thomas. Duel: Alexander Hamilton, Aaron Burr, and the Future of America. NY: Basic Books, 2000. ISBN 0465017371

- Knott, Stephen F. Alexander Hamilton and the Persistence of Myth. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2002. ISBN 0700611576

- [Lodge, Henry Cabot] George Washington, (Vol. 2, 1899 covers 1783-1799) online at Project Gutenberg Retrieved August 13, 2007.

- McDonald, Forrest. Alexander Hamilton: A Biography. NY: Norton, 1982. ISBN 039330048X (intellectual history focused on Hamilton's republicanism)

- Miller, John C. Alexander Hamilton: Portrait in Paradox. NY: Harper, 1959. ISBN 978-0060129750 (full-length scholarly biography)

- Mitchell, Broadus. Alexander Hamilton, (2 vols), NY: Macmillan 1957-62. (scholarly biography)

- Nettels, Curtis P. The Emergence of a National Economy, 1775-1815. NY: Harper & Row, 1962. (The standard economic history) ASIN B000GK7DVI

- Randall, Willard Sterne. Alexander Hamilton: A Life. NY: HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 0060195495

- Rossiter, Clinton. Alexander Hamilton and the Constitution. NY: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1964. (a conservative appraisal)

- Sharp, James. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 0300055307 (scholarly synthesis)

- Sheehan, Colleen. "Madison V. Hamilton: The Battle Over Republicanism And The Role Of Public Opinion," American Political Science Review 98(3) (2004): 405-424.

- Stourzh, Gerald. Alexander Hamilton and the Idea of Republican Government. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1970. ISBN 0804707243 (intellectual history)

- White, Leonard D. The Federalists. NY: Macmillan Co, 1949. (coverage of how the Treasury and other departments were created and operated)

- White, Richard D. "Political Economy and Statesmanship: Smith, Hamilton, and the Foundation of the Commercial Republic." Public Administration Review 60 (2000).

Primary sources

- Cooke, Jacob E. (ed) Alexander Hamilton: A Profile. NY: Hill and Wang, 1967. (short excerpts from Alexander Hamilton and his critics) ISBN 978-0809002023

- Cunningham, Noble E. Jefferson vs. Hamilton: Confrontations that Shaped a Nation. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2000. ISBN 0312085850 (short collection of primary sources with commentary)

- Frisch, Morton J. (ed.) Selected Writings and Speeches of Alexander Hamilton. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, 1985. ISBN 0844735515

- Hamilton, Alexander. Alexander Hamilton: Writings. NY: Literary Classic of the US (Library of America edition), 2001. ISBN 1931082049 (over 1000 pages)

- Morris, Richard. (ed) Alexander Hamilton and the Founding of the Nation. NY: Harper & Row, 1957. ASIN B006HVAJPC

- Syrett, Harold C. (ed) The Papers of Alexander Hamilton, (27 vols) NY: Columbia University Press, 1961-1987. ISBN 0231089260

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Hamilton's Report on Manufactures (Columbia University Press)

- The Rise and Fall of Alexander Hamilton by Ian Finseth

- Hamilton's Congressional biography

- Alexander Hamilton: Debate over a National Bank (Feb 23, 1791)

- Alexander Hamilton by C.C. Hazewell.

- Alexander Hamilton by Henry Cabot Lodge.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.