Lilith

Lilith (Hebrew לילית) is a female demon figure found in Mesopotamian mythology and Jewish folklore, associated with sexual temptation, storms, disease, illness, and death. In some Jewish mystical writings she is said to be the first wife of Adam, who refused to lie under him, and voluntarily left the Garden of Eden. She was especially feared in medieval Judaism for her purported ability to harm young children, and amulets were once worn to protect children from Lilith's harm.

Historically, the figure of Lilith first appeared in a class of wind and storm demons known as Lilitu, in Sumer, circa 3000 B.C.E. Corresponding versions of the demon were found in ancient Babylonian culture, eventually influencing the demonology of medieval Rabbinic Judaism. Lilith would become a part of Jewish lore as a night demon and was later adopted into Christianity as a "screech owl" in the King James version of the Bible.

Two primary characteristics are found in ancient and medieval legends about Lilith: first, she was seen as the incarnation of lust, causing men to be led astray, and, second, Lilith was viewed as a child-killing witch, who strangled helpless neonates. These two aspects of the Lilith legend seemed to have evolved separately, in there is hardly a tale where Lilith encompasses both roles.

The rabbinical story of Lilith offers an alternative view of the biblical creation story, seeing Lilith as Adam's first wife instead of Eve. Due to Lilith's supposed independence from Adam, she has been called "the world's first feminist."

Etymology

The Hebrew Lilith and Akkadian Lńęlńętu are female adjectives from the Proto-Semitic root LYL "night", literally translating to nocturnal "female night being/demon," although cuneiform inscriptions where Lńęlńęt and Lńęlńętu refers to disease-bearing wind spirits exist.[1] The Akkadian Lil-itu ("lady air") may be a reference to the Sumerian goddess Ninlil (also "lady air"), Goddess of the South wind and wife of Enlil. The story of Adapa tells how Adapa broke the wings of the south wind, for which he feared he would be punished with death. In ancient Iraq, the south wind was associated with the onset of summer dust storms and general ill-health. The corresponding Akkadian masculine lńęl√Ľ shows no nisba suffix and compares to Sumerian (kiskil-) lilla.

Many scholars place the origin of the phonetic name "Lilith" at somewhere around 700 B.C.E.[2]

Mythology

Mesopotamian Lilitu

Around 3000 B.C.E., Lilith's first appearance was as a class of Sumerian storm spirits called Lilitu. The Lilitu were said to prey upon children and women, and were described as associated with lions, storms, desert, and disease. Early portrayals of lilitu are known as having Zu bird talons for feet and wings.[2] Later accounts depict lilitu as a name for one figure and several spirits. Similar demons from the same class are recorded around this time frame. Lilu, a succubus, Ardat lili ("Lilith's handmaid"), who would come to men in their sleep and beget children from them, and Irdu lili, the succubus counterpart to Ardat lili.[3] These demons were originally storm and wind demons, however later etymology made them into night demons.

Babylonian texts depict Lilith as the prostitute of the goddess Ishtar. Similarly, older Sumerian accounts state that Lilitu is called the handmaiden of Inanna or 'hand of Inanna'. The texts say that "Inanna has sent the beautiful, unmarried, and seductive prostitute Lilitu out into the fields and streets in order to lead men astray."[4]

Identical to the Babylo-Sumerian Lilitu, the Akkadian Ardat-Lili and the Assyrian La-bar-tu presided over temple prostitution. Ardat is derived from "ardatu," a title of prostitutes and young unmarried women, meaning "maiden". Like Lilith, Ardat Lili was a figure of disease and uncleanliness.

Lilith is also identified with ki-sikil-lil-la-ke. a female being in the Sumerian prologue to the Gilgamesh epic.[5][6] Ki-sikil-lil-la-ke is sometimes translated as "Lila's maiden," "companion," "his beloved" or "maid," and she is described as the "gladdener of all hearts" and "maiden who screeches constantly."[2]

The earliest reference to a demon similar to Lilith and companion of Lillake/Lilith is on the Sumerian king list, where Gilgamesh's father is named as Lillu.[5] Little is known of Lillu (or Lilu, Lila) and he was said to disturb women in their sleep and function as an incubus. [7]

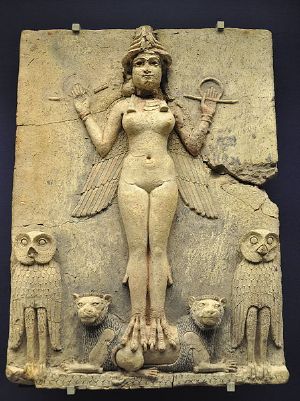

Burney Relief

The Gilgamesh passage has, in turn, been applied by some to the Burney Relief, which dates to roughly 1950 B.C.E. and is a sculpture of a woman with bird talons and flanked by owls. The relief is Babylonian, not Sumerian or Assyrian, as sometimes described. While the relief may depict the demon Kisikil-lilla-ke or Lilitu of the Gilgamesh passage, it might be a goddess. The piece is dated roughly about the same time as the Gilgamesh fragment featuring Lilith, this, in turn was used translate it as Lilith/Lillake, along with other characteristics of the female being in the Gilgamesh passage. The key identification is with the bird feet and owls. She is wearing a multiple-horned mitre and has wings, both indications of high divinity. The objects in both her hands are symbols of divine authority. However, the relief is also thought to be of the Sumerian goddess Inanna (or her underworld sister Ereshkigal) and some scholars currently regard the connection with this relief and Lilitu/Lillake as dubious.[8] According to the Anchor Bible Dictionary:

"Two sources of information previously used to define Lilith are both suspect. Kramer translated Ki-sikil-lil-la-ke as "Lilith", in a Sumerian Gilgamesh fragment. The text relates an incident where this female takes up lodging in a tree trunk which has a Zu-bird perched in the branches and a snake living in the roots. This text was used to interpret a sculpture of a woman with bird talons for feet as being a depiction of Lilith. From the beginning this interpretation was questioned so that after some debate neither the female in the story, nor the figure is assumed to be Lilith."[9]

Lilith is further associated with the Anzu bird, (Kramer translates the Anzu as owls, but most often its translated as eagle, vulture, or a bird of prey.) lions, owls, and serpents, which eventually became her cult animals. It is from this mythology that the later Kabbalah depictions of Lilith as a serpent in the Garden of Eden and her associations with serpents are probably drawn. Other legends describe the malevolent Anzu birds as a "lion-headed" and pictures them as an eagle monster,[10] likewise to this a later amulet from Arslan Tash site features a sphinx-like creature with wings devouring a child and has an incantation against Lilith or similar demons, incorporating Lilith's cult animals of lions and owls or birds.[2]

The relief was purchased by the British Museum in London for its 250th anniversary celebrations. Since then it was renamed "Queen of the Night" and has toured museums around Britain.

Lilith seems to have inherited another Mesopotamian demon's myths.[2] Lamashtu was considered to be a demi-goddess. Many incantations against her mention her status as a daughter of heaven and exercising her free will over infants. This makes her different from the rest of the demons in Mesopotamia. Unlike her demonic peers, Lamashtu was not instructed by the gods to do her malevolence, she did it on her own accord. She was said to seduce men, harm pregnant women, mothers, and neonates, kill foliage, drink blood, and was a cause of disease, sickness, and death. The space between her legs is as a scorpion, corresponding to the astrological sign of Scorpio. (Scorpio rules the genitals and sex organs.) Her head is that of a lion, she has Anzu bird feet like Lilitu and is lion headed, her breasts are suckled by a pig and a dog, and she rides the back of a donkey.[11]

Greek Mythology

Another similar monster was the Greek Lamia, who likewise governed a class of child-stealing lamia-demons. Lamia bore the title "child-killer" and, like Lilith, was feared for her malevolence, like Lilith.[12] She is described as having a human upper body from the waist up and a serpentine body from the waist down.[2] Some depictions of Lamia picture her as having wings and feet of a bird, rather than being half serpent, similar to the earlier reliefs of Greek Sirens and the Lilitu. One source states simply that she is a daughter of the goddess Hecate. Another says that Lamia was subsequently cursed by the goddess Hera to have stillborn children because of her association with Zeus. Alternately, Hera slayed all of Lamia's children (except Scylla) in anger that Lamia slept with her husband, Zeus. The grief is said to have caused Lamia to turn into a monster that took revenge on mothers by stealing their children and devouring them: "Lamia had a vicious sexual appetite that matched her cannibalistic appetite for children. She was notorious for being a vampiric spirit and loved sucking men’s blood."[2]

Her gift was the "mark of a Sibyl," a gift of second sight. However, she was "cursed" to never be able to shut her eyes so that she would forever obsess over her dead children. Taking pity on Lamia, Zeus give her the ability to take her eyes out and in from her eye sockets.[2]

Karina of Arabic lore is considered to be Lilith‚Äôs equal. She is mentioned as a child stealing and child killing witch. In this context, Karina plays the role of a ‚Äúshadow‚ÄĚ of a woman and a corresponding male demon, Karin, is the ‚Äúshadow‚ÄĚ of a man. Should a woman marry her Karina marries the man‚Äôs Karin. When the woman becomes pregnant is when Karina will cause her chaos. She will try to drive the woman out and take her place, cause a miscarriage by striking the woman and if the woman succeeds in having children than her Karina will have the same amount of children she does. The Karina will continuously try to create discord among the woman and her husband. Here, Karina plays the role of disrupter of marital relations, akin to one of Lilith‚Äôs roles in Jewish tradition.[2]

Lilith in the Bible

The only occurrence of Lilith in the Hebrew Bible is found in the Book of Isaiah 34:14, describing the desolation of Edom:

"The wild beasts of the desert shall also meet with the wild beasts of the island, and the satyr shall cry to his fellow; the "screech owl" also shall rest there, and find for herself a place of rest." (KJV)

This passage refers to Yahweh’s day of vengeance, when the land will be transformed into desolate wilderness.

Isaiah dates to the sixth century B.C.E., and the presence of Hebrews (Jews) in Babylon would coincide with the attested references to the Lńęlńętu in Babylonian demonology. Thus, Lilith was known in ancient Israel of the eighth century B.C.E. The fact that she found a place of rest in the desert from this passage seems to allude to the Sumerian Gilgamesh incident: after Lilith fled into the desert she apparently found repose there.[3]

Schrader (Jahrbuch f√ľr Protestantische Theologie, 1. 128) and Levy (ZDMG 9. 470, 484) suggest that Lilith was a goddess of the night, known also by the Jewish exiles in Babylon. Evidence for Lilith being a goddess rather than a demon is lacking.

The Septuagint translates onokentauros, apparently for lack of a better word, since also the sa Ņir "satyrs" earlier in the verse are translated with daimon onokentauros. The "wild beasts of the island and the desert" are omitted altogether, and the "crying to his fellow" is also done by the daimon onokentauros.

The screech owl translation of the King James Version of the Bible (1611 C.E.)is without precedent, and apparently together with the "owl" (yanŇ°up, probably a water bird) in 34:11, and the "great owl" (qippoz, properly a snake,) of 34:15 an attempt to render the eerie atmosphere of the passage by choosing suitable animals for difficult-to-translate Hebrew words. It should be noted that this particular species of owl is associated with the vampiric Strix (a nocturnal bird of ill omen that fed on human flesh and blood) of Roman legend.[13]

Later translations include:

- night-owl (Young, 1898)

- night monster (American Standard Version, 1901; NASB, 1995)

- vampires (Moffatt Translation, 1922)

- night hag (Revised Standard Version, 1947)

- lilith (New American Bible, 1970)

- night creature (NIV, 1978; NKJV, 1982; NLT, 1996)

- nightjar (New World Translation, 1984).

Jewish tradition

A Hebrew tradition exists in which an amulet is inscribed with the names of three angels (Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof) and placed around the neck of newborn boys in order to protect them from the lilin until their circumcision. There is also a Hebrew tradition to wait three years before a boy's hair is cut so as to attempt to trick Lilith into thinking the child is a girl so that the boy's life may be spared.

Dead Sea scrolls

The appearance of Lilith in the Dead Sea Scrolls is somewhat more contentious, with one indisputable reference in the Song for a Sage (4Q510-511), and a promising additional allusion found by A. Baumgarten in The Seductress (4Q184). The first and irrefutable Lilith reference in the Song occurs in 4Q510, fragment 1:

"And I, the Instructor, proclaim His glorious splendour so as to frighten and to te[rrify] all the spirits of the destroying angels, spirits of the bastards, demons, Lilith, howlers, and [desert dwellers‚Ķ] and those which fall upon men without warning to lead them astray from a spirit of understanding and to make their heart and their [‚Ķ] desolate during the present dominion of wickedness and predetermined time of humiliations for the sons of lig[ht], by the guilt of the ages of [those] smitten by iniquity ‚Äď not for eternal destruction, [bu]t for an era of humiliation for transgression."

Akin to Isaiah 34:14, this liturgical text both cautions against the presence of supernatural malevolence and assumes familiarity with Lilith; distinct from the biblical text, however, this passage does not function under any socio-political agenda, but instead serves in the same capacity as An Exorcism (4Q560) and Songs to Disperse Demons (11Q11) insomuch that it comprises incantations ‚Äď comparable to the Arslan Tash relief examined above ‚Äď used to "help protect the faithful against the power of these spirits." The text is thus an exorcism hymn.

Another text discovered at Qumran, conventionally associated with the Book of Proverbs, credibly also appropriates the Lilith tradition in its description of a precarious, winsome woman ‚Äď The Seductress (4Q184). The ancient poem ‚Äď dated to the first century B.C.E. but plausibly much older ‚Äď describes a dangerous woman and consequently warns against encounters with her. Customarily, the woman depicted in this text is equated to the "strange woman" of Proverbs 2 and 5, and for good reason; the parallels are instantly recognizable:

"Her house sinks down to death,

And her course leads to the shades. All who go to her cannot return And find again the paths of life."

(Proverbs 2:18-19)

"Her gates are gates of death,

and from the entrance of the house she sets out towards Sheol. None of those who enter there will ever return, and all who possess her will descend to the Pit."

(4Q184)

However, what this association does not take into account are additional descriptions of the "Seductress" from Qumran that cannot be found attributed to the "strange woman" of Proverbs; namely, her horns and her wings: "a multitude of sins is in her wings." The woman illustrated in Proverbs is without question a prostitute, or at the very least the representation of one, and the sort of individual with whom that text‚Äôs community would have been familiar. The "Seductress" of the Qumran text, conversely, could not possibly have represented an existent social threat given the constraints of this particular ascetic community. Instead, the Qumran text utilizes the imagery of Proverbs to explicate a much broader, supernatural threat ‚Äď the threat of the demoness Lilith.

Talmud

Although the Talmudic references to Lilith are sparse, these passages provide the most comprehensive insight into the demoness yet seen in Judaic literature that both echo Lilith’s Mesopotamian origins and prefigure her future as the perceived exegetical enigma of the Genesis account. Recalling the Lilith we have seen, Talmudic allusions to Lilith illustrate her essential wings and long hair, dating back to her earliest extant mention in Gilgamesh:

"Rab Judah citing Samuel ruled: If an abortion had the likeness of Lilith its mother is unclean by reason of the birth, for it is a child but it has wings." (Niddah 24b)

More unique to the Talmud with regard to Lilith is her insalubrious carnality, alluded to in The Seductress but expanded upon here sans unspecific metaphors as the demoness assuming the form of a woman in order to sexually take men by force while they sleep:

- "R. Hanina said: One may not sleep in a house alone [in a lonely house], and whoever sleeps in a house alone is seized by Lilith." (Shabbath 151b)

Yet the most innovative perception of Lilith offered by the Talmud appears earlier in ‚ÄėErubin, and is more than likely inadvertently responsible for the fate of the Lilith myth for centuries to come:

- "R. Jeremiah b. Eleazar further stated: In all those years [130 years after his expulsion from the Garden of Eden] during which Adam was under the ban he begot ghosts and male demons and female demons [or night demons], for it is said in Scripture, And Adam lived a hundred and thirty years and begot a son in own likeness, after his own image, from which it follows that until that time he did not beget after his own image‚ĶWhen he saw that through him death was ordained as punishment he spent a hundred and thirty years in fasting, severed connection with his wife for a hundred and thirty years, and wore clothes of fig on his body for a hundred and thirty years. ‚Äď That statement [of R. Jeremiah] was made in reference to the semen which he emitted accidentally." (‚ÄėErubin 18b)

Comparing Erubin 18b and Shabbath 151b with the later passage from the Zohar: ‚ÄúShe wanders about at night, vexing the sons of men and causing them to defile themselves (19b),‚ÄĚ it appears clear that this Talmudic passage indicates such an averse union between Adam and Lilith.

Folk tradition

The Alphabet of Ben Sira, one of the earliest literary parodies in Hebrew literature, is considered to be the oldest form of the story of Lilith as Adam's first wife. Whether or not this certain tradition is older is not known. Scholars tend to date Ben Sira between eighth and tenth centuries. Its real author is anonymous, but it is falsely attributed to the sage Ben Sira. The amulets used against Lilith that were thought to derive from this tradition are in fact, dated as being much older.[14] While the concept of Eve having a predecessor is not exclusive to Ben Sira, or new, and can be found in Genesis Rabbah, the idea that this predecessor was Lilith is. According to Gershom Scholem, the author of the Zohar, R. Moses de Leon, was aware of the folk tradition of Lilith, as well another story, possibly older, that may be conflicting.[15]

The idea that Adam had a wife prior to Eve may have developed from an interpretation of the Book of Genesis and its dual creation accounts; while Genesis 2:22 describes God's creation of Eve from Adam's rib, an earlier passage, 1:27, already indicates that a woman had been made: "So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them." The text places Lilith's creation after God's words in Genesis 2:18 that "it is not good for man to be alone". He forms Lilith out of the clay from which he made Adam, but the two bicker. Lilith claims that since she and Adam were created in the same way, they were equal, and she refuses to "lie below" him:

After God created Adam, who was alone, He said, 'It is not good for man to be alone.' He then created a woman for Adam, from the earth, as He had created Adam himself, and called her Lilith. Adam and Lilith immediately began to fight. She said, 'I will not lie below,' and he said, 'I will not lie beneath you, but only on top. For you are fit only to be in the bottom position, while I am to be the superior one.' Lilith responded, 'We are equal to each other inasmuch as we were both created from the earth.' But they would not listen to one another. When Lilith saw this, she pronounced the Ineffable Name and flew away into the air.

Adam stood in prayer before his Creator: 'Sovereign of the universe!' he said, 'the woman you gave me has run away.' At once, the Holy One, blessed be He, sent these three angels Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof, to bring her back. "Said the Holy One to Adam, 'If she agrees to come back, what is made is good. If not, she must permit one hundred of her children to die every day.' The angels left God and pursued Lilith, whom they overtook in the midst of the sea, in the mighty waters wherein the Egyptians were destined to drown. They told her God's word, but she did not wish to return. The angels said, 'We shall drown you in the sea.'

"'Leave me!' she said. 'I was created only to cause sickness to infants. If the infant is male, I have dominion over him for eight days after his birth, and if female, for twenty days.' "When the angels heard Lilith's words, they insisted she go back. But she swore to them by the name of the living and eternal God: 'Whenever I see you or your names or your forms in an amulet, I will have no power over that infant.' She also agreed to have one hundred of her children die every day. Accordingly, every day one hundred demons perish, and for the same reason, we write the angels names on the amulets of young children. When Lilith sees their names, she remembers her oath, and the child recovers."

The background and purpose of The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is unclear. It is a collection of 22 stories (one for each letter of the Hebrew alphabet) about heroes of the Bible and Talmud; it may have been a collection of folktales, a refutation of Christian, Karaite, or other separatist movements; its content seems so offensive to contemporary Jews that it was even suggested that it could be an anti-Jewish satire,[16] although, in any case, the text was accepted by the Jewish mystics of medieval Germany.

The Alphabet of Ben-Sira is the earliest surviving source of the story, and the conception that Lilith was Adam's first wife became only widely known with the seventeenth century Lexicon Talmudicum of Johannes Buxtorf.

In the folk tradition that arose in the early Middle Ages, Lilith, a dominate female demon, became identified with Asmodeus, King of Demons, as his queen. Asmodeus was already well known by this time because of the legends about him in the Talmud. Thus, the merging of Lilith and Asmodeus was inevitable.[17] The fecund myth of Lilith grew to include legends about another world and by some accounts this other world existed side by side with this one, Yenne Velt is Yiddish for this described "Other World." In this case, Asmodeus and Lilith were believed to procreate demonic offspring endlessly and spread chaos at every turn.[17] Many disasters were blamed on both of them, causing wine to turn into vinegar, men to be impotent, women unable to give birth, and it was Lilith who was blamed for the loss of infant life. The presence of Lilith and her cohorts were considered very real at this time.

Two primary characteristics are seen in these legends about Lilith: Lilith as the incarnation of lust, causing men to be led astray, and Lilith as a child killing witch, who strangles helpless neonates. These two aspects of the Lilith legend seemed to have evolved separately, in there is hardly a tale were Lilith encompasses both roles.[17] But the aspect of the witch-like role that Lilith plays broadens her archetype of the destructive side of witchcraft. Such stories are commonly found among Jewish folklore.[17]

It is said that "every mirror is a passage into the Otherworld and leads to the cave that Lilith went to after she had abandoned Adam and Eden for all time." In this cave, Lilith takes up demon lovers, who father upon her multitudes of demons who flock from the cave and infest the world. When these demons want to return they simply enter the nearest mirror.[17]

In Horace (De Arte Poetica liber, 340), Hieronymus of Cardia translated Lilith as Lamia, a witch who steals children, similar to the Breton Korrigan, in Greek mythology described as a Libyan queen who mated with Zeus. After Zeus abandoned Lamia, Hera stole Lamia's children, and Lamia took revenge by stealing other women's children.

Kabbalah

The major characteristics of Lilith were well developed by the end of the Talmudic period. Kabbalistic mysticism, therefore, established a relationship between her and deity. Six centuries elapsed between the Aramiac incantation texts that mention Lilith and the early Spanish Kabbalistic writings. In the 13 centuries she reappears and her life history becomes known in greater mythological detail.[3]

Her creation is described in many alternative versions. One mentions her creation as being before Adam's, on the fifth day. Because the "living creature" with whose swarms God filled the waters was none other than Lilith. A similar version, related to the earlier Talmudic passages, recounts how Lilith was fashioned with the same substance as Adam, shortly before. A third alternative version states that God originally created Adam and Lilith in a manner that the female creature was contained in the male. Lilith's soul was lodged in the depths of the Great Abyss. When she was called by God she joined Adam. After Adam's body was created a thousand souls from the Left (evil) side attempted to attach themselves to him. But God drove them off. Adam was left laying as a body without a soul. Then a cloud descended and God commanded the earth to produce a living soul. This God breathed into Adam, who began to spring to life and his female was attached to his side. God separated the female from Adam's side. The female side was Lilith, whereupon she flew to the Cities of the Sea and attacks mankind. Yet another version claims that Lilith was not created by God, but emerged as a divine entity that was born spontaneously, either out of the Great Supernal Abyss or out of the power of an aspect of God (the Gevurah of Din). This aspect of God, one of his ten attributes (Sefirot), at its lowest manifestation has an affinity with the realm of evil, and it is out of this that Lilith merged with Samael.[3]

Adam and Lilith

The first medieval source to depict the myth of Adam and Lilith in full was the Midrash Abkier (ca. tenth century), which was followed by the Zohar and Kabblistic writings. Adam is said to be a perfect saint until he either recognizes his sin, or Cain's homicide that is the cause of bringing death into the world. He then separates from holy Eve, sleeps alone, and fasts for 130 years. During this time Lilith, also known as Pizna, and Naamah desired his beauty and came to him against his will. They bore him many demons and spirits called "the plagues of humankind."[3] The added explanation was that it was Adam's own sin that Lilith overcame him against his will.

Older sources do not state clearly that after Lilith's Red Sea sojourn, she returned to Adam and beget children from him. In the Zohar, however, Lilith is said to have succeeded in begetting offspring from Adam during their short lived connubium. Lilith leaves Adam in Eden as she is not a suitable companion for him. She returns, later, to force herself upon him. But before doing so she attaches herself to Cain and bears him numerous spirits and demons.[3]

The Two Liliths

A passage in the thirteenth century document called the Treatise on the Left Emanation explains that there are two "Liliths." The Lesser being married to the great demon Asmodeus.

In answer to your question concerning Lilith, I shall explain to you the essence of the matter. Concerning this point there is a received tradition from the ancient Sages who made use of the Secret Knowledge of the Lesser Palaces, which is the manipulation of demons and a ladder by which one ascends to the prophetic levels. In this tradition it is made clear that Samael and Lilith were born as one, similar to the form of Adam and Eve who were also born as one, reflecting what is above. This is the account of Lilith which was received by the Sages in the Secret Knowledge of the Palaces. The Matron Lilith is the mate of Samael. Both of them were born at the same hour in the image of Adam and Eve, intertwined in each other. Asmodeus the great king of the demons has as a mate the Lesser (younger) Lilith, daughter of the king whose name is Qafsefoni. The name of his mate is Mehetabel daughter of Matred, and their daughter is Lilith.[18]

Another passage charges Lilith as being a tempting serpent of Eve's:

And the Serpent, the Woman of Harlotry, incited and seduced Eve through the husks of Light which in itself is holiness. And the Serpent seduced Holy Eve, and enough said for him who understands. An all this ruination came about because Adam the first man coupled with Eve while she was in her menstrual impurity ‚Äď this is the filth and the impure seed of the Serpent who mounted Eve before Adam mounted her. Behold, here it is before you: because of the sins of Adam the first man all the things mentioned came into being. For Evil Lilith, when she saw the greatness of his corruption, became strong in her husks, and came to Adam against his will, and became hot from him and bore him many demons and spirits and Lilin.[3]

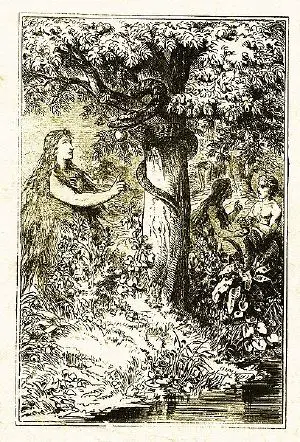

This may relate to various late medieval iconography of a female serpent figure, believed to be Lilith, tempting Adam and Eve. The prophet Elijah is said to have confronted Lilith in one text. In this encounter she had come to feast on the flesh of the mother, with a host of demons, and take the new born from her. She eventually reveals her secret names to Elijah in the conclusion. These names are said to cause Lilith to lose her power: lilith, abitu, abizu, hakash, avers hikpodu, ayalu, matrota… In others, probably informed by The Alphabet of Ben-Sira, she is Adam's first wife (Yalqut Reubeni, Zohar 1:34b, 3:19).[19]

Lilith is listed as one of the Qliphoth, corresponding to the Sephirah Malkuth in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life.

The Qliphah is the unbalanced power of a Sephirah. Malkuth is the lowest Sephirah, the realm of the earth, into which all the divine energy flows, and in which the divine plan is worked out. However, its unbalanced form as Lilith, the seductress, is obvious. The material world, and all of its pleasures, is the ultimate seductress, and can lead to materialism unbalanced by the spirituality of the higher spheres. This ultimately leads to a descent into animal consciousness. The balance must therefore be found between Malkuth and Kether, to find order and harmony, without giving into Lilith, materialism, or Thaumiel, Satan, spiritual pride and egotism.

Lilith in the Romantic period

Lilith's earliest appearance in the literature of the Romantic period (1789-1832) was in Goethe's 1808 work Faust Part I, nearly 600 years after appearing in the Kabbalistic Zohar:

Faust:

Who's that there?Mephistopheles:

Take a good look.

Lilith.Faust:

Lilith? Who is that?Mephistopheles:

Adam's wife, his first. Beware of her.

Her beauty's one boast is her dangerous hair.

When Lilith winds it tight around young men

She doesn't soon let go of them again.(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4206‚Äď4211)

After Mephistopheles offers this warning to Faust, he then, quite ironically, encourages Faust to dance with "the Pretty Witch". Lilith and Faust engage in a short dialogue, where Lilith recounts the days spent in Eden.

Faust: [dancing with the young witch]

A lovely dream I dreamt one day

I saw a green-leaved apple tree,

Two apples swayed upon a stem,

So tempting! I climbed up for them.The Pretty Witch:

Ever since the days of Eden

Apples have been man's desire.

How overjoyed I am to think, sir,

Apples grow, too, in my garden.(1992 Greenberg translation, lines 4216 ‚Äď 4223)

With her "ensnaring" sexuality, Goethe draws upon ancient legends of Lilith that identify her as the first wife of Adam. This image is the first "modern" literary mention of Lilith and continues to dominate throughout the nineteenth century.

Keats' Lamia and Other Poems (1819), was important in creating the Romantic "seductress" stock characters that drew from the myths of Lamia and Lilith. The central figure of Keats' "La Belle Dame Sans Merci" may also be Lilith.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, which developed around 1848, were greatly influenced by Goethe's and Keats' work on the theme of Lilith. In 1863, Dante Gabriel Rossetti of the Brotherhood began painting what would be his first rendition of "Lady Lilith," a painting he expected to be his best picture. Symbols appearing in the painting allude to the "femme fatale" reputation of the Romantic Lilith: poppies (death and cold) and white roses (sterile passion). Accompanying his Lady Lilith painting from 1863, Rossetti wrote a sonnet entitled Lilith, which was first published in Swinburne's pamphlet-review (1868), Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition:

Of Adam's first wife, Lilith, it is told

(The witch he loved before the gift of Eve,)

That, ere the snake's, her sweet tongue could deceive,

And her enchanted hair was the first gold.

And still she sits, young while the earth is old,

And, subtly of herself contemplative,

Draws men to watch the bright web she can weave,

Till heart and body and life are in its hold.

The rose and poppy are her flower; for where

Is he not found, O Lilith, whom shed scent

And soft-shed kisses and soft sleep shall snare?

Lo! as that youth's eyes burned at thine, so went

Thy spell through him, and left his straight neck bent

And round his heart one strangling golden hair.

[20]

The poem and the picture appeared together alongside Rossetti's painting Sibylla Palmifera and the sonnet Soul's Beauty. In 1881, the Lilith sonnet was renamed "Body's Beauty" in order to contrast it and Soul's Beauty. The two were placed sequentially in The House of Life collection (sonnets number 77 and 78).

Rossetti was aware that this modern view was in complete contrast to her Jewish lore; he wrote in 1870:

- Lady [Lilith]...represents a ‚ÄėModern Lilith‚Äô combing out her abundant golden hair and gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their own circle."[21]

The Victorian poet Robert Browning re-envisioned Lilith in his poem "Adam, Lilith, and Eve". First published in 1883, the poem uses the traditional myths surrounding the triad of Adam, Eve, and Lilith. Browning depicts Lilith and Eve as being friendly and complicitous with each other, as they sit together on either side of Adam. Under the threat of death, Eve admits that she never loved Adam, while Lilith confesses that she always loved him:

As the worst of the venom left my lips,

I thought, 'If, despite this lie, he strips

The mask from my soul with a kiss ‚ÄĒ I crawl

His slave, ‚ÄĒ soul, body, and all!

Browning 1098

Browning focused on Lilith's emotional attributes, rather than that of her ancient demon predecessors.[22] Such contemporary representations of Lilith continue to be popular among modern Pagans and feminists alike.

The Modern Lilith

Ceremonial magick

Few magickal orders exist dedicated to the undercurrent of Lilith and deal in initiations specifically related to the Aracana of the first Mother. Two organizations that progressively use initiations and magick associated with Lilith are the Ordo Antichristianus Illuminati and the Order of Phosphorus (see excerpt below). Lilith appears as a succubus in Aleister Crowley's De Arte Magica. Lilith was also one of the middle names of Crowley‚Äôs first child, Ma Ahathoor Hecate Sappho Jezebel Lilith Crowley (1904 ‚Äď 1906). She is sometimes identified with Babalon in Thelemic writings. A Thelemic rite, based on an earlier German rite, offers the invocation of Lilith.

Dark is she, but brilliant! Black are her wings, black on black! Her lips are red as rose, kissing all of the Universe! She is Lilith, who leadeth forth the hordes of the Abyss, and leadeth man to liberation! She is the irresistible fulfiller of all lust, seer of desire. First of all women was she - Lilith, not Eve was the first! Her hand brings forth the revolution of the Will and true freedom of the mind! She is KI-SI-KIL-LIL-LA-KE, Queen of the Magic! Look on her in lust and despair![23]

Modern Luciferianism

In modern Luciferianism, Lilith is considered a consort and/or an aspect of Lucifer and is identified with the figure of Babalon. She is said to come from the mud and dust, and is known as the Queen of the Succubi. When she and Lucifer mate, they form an androgynous being called "Baphomet" or the "Goat of Mendes," also known in Luciferianism as the "God of Witches."[24]

Michael Ford, Left-Hand Path adept and magician, musician, self-published writer, and a co-president of the short-lived Greater Church of Lucifer, contends that Lilith forms the "Luciferian Trinity," composed of her, Samael, and Cain. Likewise, she is said to have been Cain's actual mother, as opposed to Eve. Lilith here is seen as a goddess of witches, the dark feminine principle, and is also known as the goddess Hecate.[25]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Archibald H. Sayce, Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians (Alpha Edition, 2020, ISBN 978-9354004193).

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Siegmund Hurwitz, Lilith - The first Eve (Switzerland: Daminon Press, 2009, ISBN 978-3856307325).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Raphael Patai, The Hebrew Goddess (Wayne State University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0814322710).

- ‚ÜĎ Stephen H. Langdon, The Mythology of All Races Volume V Semitic (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1975, ISBN 978-0815401339).

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 Raphael Patai, Adam ve-Adama, trans. as Man and Earth (Jerusalem: The Hebrew Press Association, 1941-1942).

- ‚ÜĎ Diane Wolkstein and Samuel Noah Kramer, Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth (New York: Harper & Row, 1983, ISBN 0060908548).

- ‚ÜĎ T.H. Jacobsen, "Mesopotamia", in Henri Frankfort, Before Philosophy: The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man (Penguin Books, 1946, ISBN 978-0140201987).

- ‚ÜĎ Alan Humm, Lilith Pictures: Ancient and Magical Lilith. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Lowell K. Handy, "Lilith" in David Noel Freedman, The Anchor Bible Dictionary Vol, 4 (Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1992, ISBN 978-0385425834), 324.

- ‚ÜĎ Stephanie Dalley, (translator) Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh and others (Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 0192835890).

- ‚ÜĎ Margi B., Lilith - Before the Alphabet of Ben Sira Bbibliotecapleyades. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ The Lilith Myth The Gnosis Archive. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Samuel Grant Oliphant, The Story of the Strix: Ancient Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 44 (1913): 133-149.

- ‚ÜĎ Alan Humm, The Story of Lilith Lilith. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Gershom Scholem, Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism (Schocken, 1995, ISBN 0805210423), 174.

- ‚ÜĎ Eliezer Segal, Looking for Lilith Jewish Free Press, Feb. 6, 1995. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Howard Schwartz, Lilith's Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural (Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0195067262).

- ‚ÜĎ R. Isaac b. Jacob Ha-Kohen, Tr. Ronald C. Kiener, Lilith in Jewish Mysticism: Treatise on the Left Emanation Lilith. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Alan Humm, Kabbala: Lilith's Origins Lilith. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ W.M. Rossetti and A.C. Swinburne, Notes on the Royal Academy Exhibition, 1868: Lady Lilith Rossetti Archive Textual Transcription. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Lady Lilith: Scholarly Commentary Rossetti Archive. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Kathryn Lee Seidel, The Lilith Figure in Toni Morrison's Sula and Alice Walker's The Color Purple.

- ‚ÜĎ The Invocation of Lilith, A Rite of Dark Sexuality Lilith's World. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Baphomet Occult World. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ‚ÜĎ Michael Ford, Black Witchcraft, Foundations of the Luciferian Path Retrieved July 24, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dalley, Stephanie, translator. Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh and others. Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0192835890

- Frankfort, Henri. Before Philosophy: The Intellectual Adventure of Ancient Man. Penguin Books, 1946. ISBN 978-0140201987

- Freedman, David Noel. The Anchor Bible Dictionary. Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, Inc., 1992. ISBN 978-0385425834

- Graves, Robert, and Raphael Patai. Hebrew Myths: The Book of Genesis. New York: Random House, 1986. ISBN 978-0517413661

- Hurwitz, Siegmund. Lilith - The first Eve, 2nd edition. Switzerland: Daminon Press, (original 1992) 2009. ISBN 978-3856307325

- Kramer's Translation of the Gilgamesh Prologue. Kramer, Samuel Noah. "Gilgamesh and the Huluppu-Tree: A reconstructed Sumerian Text." Assyriological Studies of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 10. Chicago: 1938. reprint ed. Kessinger Publishing, 2007. ISBN 1432628194.

- Langdon, Stephen L. The Mythology of All Races Volume V Semitic. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1975. ISBN 978-0815401339

- Oliphant, Samuel Grant. "The Story of the Strix: Ancient". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 44 (1913): 133-149.

- Patai, Raphael. Adam ve-Adama, tr. as Man and Earth. Jerusalem: The Hebrew Press Association, 1941-1942.

- Patai, Raphael. The Hebrew Goddess. Wayne State University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0814322710

- Plaskow, Judith. "The Coming of Lilith: A Response" Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion 23 (1) (Spring 2007): 34-41.

- Sayce, Archibald H. Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion as Illustrated by the Religion of the Ancient Babylonians Alpha Edition, 2020 (original 1887). ISBN 978-9354004193

- Schwartz, Howard. Lilith's Cave: Jewish tales of the supernatural. Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0195067262

- Scholem, Gershom. Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism. Schocken, 1995. ISBN 0805210423

- Stern, David, and Mark Jay Mirsky ( eds.). Rabbinic Fantasies: Imaginative Narratives from Classical Hebrew Literature. Yale University Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0300074024

- Wolkstein, Diane, and Samuel Noah Kramer. Inanna: Queen of Heaven and Earth: Her Stories and Hymns from Sumer. New York: Harper & Row, 1983. ISBN 0060908548

External links

All links retrieved March 11, 2025.

- Lilith Jewish Encyclopedia

- The Lilith Myth The Gnosis Archive

- Lilith Jewish Women's Archive

- Revisioning Lilith The Lilith Institute

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.