Demon

In religion, folklore, and mythology, a demon (also rendered daemon, dæmon, or daimon) is a supernatural being of malevolent intent, or a fallen angel not following God. Many religions speak of demonic forces within the cosmos representing the antithesis of truth and goodnessâforces which are ultimately vanquished in the triumph of good over evil, or truth over untruth.

Most religions and cultures of the world accept the existence of demons, while modern secularists regard belief in demons as superstition. Demons are frequently depicted as spirits that may be conjured and insecurely controlled through the practice of exorcisms. Their alleged power to possess living creatures and dangerously influence human behavior is regarded by many Christians as a cause of mental illness, although such beliefs are rejected by mainstream psychology.

In common language, to "demonize" a person means to characterize or portray them as evil, or as a source of evil.

Etymology

The word Demon derives from the Greek δαίμÏν (daimÅn), which itself comes from the verb daiesthai, meaning "to divide, distribute."[1] The Proto-Indo-European root deiwos for god, originally an adjective meaning "celestial" or "bright, shining" has retained this meaning in many related Indo-European languages and Indo-Europeans cultures (Sanskrit Deva (Hinduism), Latin Deus, German Tiw, Welsh Duw, Lithuanian Dievas), but also provided another other common word for demon in Avestan daeva.

Though the modern Greek word, daimÅn, has the same meaning as the modern English demon, it should be noted that in Ancient Greece, δαίμÏν meant "spirit" or "higher self," much like the Latin genius.

Demons in the Hebrew Bible

Demons as described in the Tanakh are not the same as "demons" commonly known in popular or Christian culture.

Those in the Hebrew Bible are of two classes, the se'irim and the shedim. The se'irim ("hairy beings"), to which some Israelites offered sacrifices in the open fields, are satyr-like creatures, described as dancing in the wilderness (Isaiah 13:21, 34:14), and which are identical with the jinn, such as Dantalion, the 71st spirit of Solomon. Possibly to the same class belongs Azazel, the goat-like demons of the wilderness (Leviticus 16:10ff), probably the chief of the se'irim, and Lilith (Isaiah 34:14). Possibly "the roes and hinds of the field," by which Shulamit conjures the daughters of Jerusalem to bring her back to her lover (Canticles 2:7, 3:5), are faun-like spirits similar to the se'irim, though of a harmless nature.

Shedim are demons that are mentioned in Psalms 106:37. The word "Shedim" is plural for "demon." Figures that represent shedim are the shedu of Babylonian mythology. These figures were depicted as anthropomorphic, winged bulls, associated with wind. They were thought to guard palaces, cities, houses, and temples. In magical texts of that era, they could either be malevolent or benelovent.[2] The cult was said to include human sacrifice as part of its practice.

Shedim in Jewish thought and literature were portrayed as quite malevolent. Some writings contend that they are storm-demons. Their creation is presented in three contradicting Jewish tales. The first is that during Creation, God created the shedim but did not create their bodies and forgot them on the Sabbath, when he rested. The second is that they are descendants of demons in the form of serpents, and the last states that they are simply descendants of Adam & Lilith. Another story asserts that after the tower of Babel, some people were scattered and became Shedim, Ruchin, and Lilin. The shedim are supposed to follow the dead or fly around graves, and some are reputed to have had the legs of a cock.

It was thought that sinful people sacrificed their daughters to the shedim, but it is unclear whether the sacrifice consisted in the murdering of the victims or in the sexual satisfaction of the demons. To see if these demons were present in some place, ashes were thrown to the ground or floor, and then their footsteps allegedly became visible.

Other Jewish literature says that the shedim were storm-demons, taken from Chaldean mythology that had seven evil storm-demons, called shedim and represented in ox-like form, but these ox-like representations were also protective spirits of royal palaces, and became a synonym of propitious deities or demons for the Babylonians.

This word is a plural, and although the nature and appearance of these dangerous Jewish demons is very different according to one of the legends, the name was surely taken from shedu. It was perhaps due to the fact that the shedu were often depicted as bulls, and this was associated with the sacrifices made in honor of other gods depicted as bulls or wearing bull's horns, like Moloch and Baal, and to the fact that Pagan deities were easily turned into demons by monotheistic religions.

Some benevolent shedim were used in kabbalistic ceremonies (as with the golem of Rabbi Yehuda Loevy), and malevolent shedim (mazikin, from the root meaning "to wound") are often responsible in instances of possession. Instances of idol worship were often the result of a shed inhabiting an otherwise worthless statue; the shed would pretend to be a God with the power to send pestilence, although such events were not actually under his control.

In Hebrew, demons were workers of harm. To them are ascribed the various diseases, particularly ones that affect the brain and the inner parts. Hence, there was a fear of "Shabriri" (lit. "dazzling glare"), the demon of blindness, who rests on uncovered water at night and strikes those with blindness who drink of it;[3] also mentioned were the spirit of catalepsy and the spirit of headache, the demon of epilepsy, and the spirit of nightmare.

These demons were supposed to enter the body and cause the disease while overwhelming, or "seizing," the victim (hence "seizure"). To cure such diseases it was necessary to draw out the evil demons by certain incantations and talismanic performances, in which the Essenes excelled. Josephus, who speaks of demons as "spirits of the wicked which enter into men that are alive and kill them," but which can be driven out by a certain root,[4] witnessed such a performance in the presence of the Emperor Vespasian,[5] and ascribed its origin to King Solomon.

There are indications that popular Hebrew mythology ascribed to the demons a certain independence, a malevolent character of their own, because they are believed to come forth, not from the heavenly abode of God, but from the nether world (Isaiah xxxviii. 11). In II Samuel xxiv; 16 and II Chronicles xxi. 15, the pestilence-dealing demon is called "the destroying angel" (compare "the angel of the Lord" in II Kings xix. 35; Isaiah xxxvii. 36), because, although they are demons, these "evil messengers" (Psalms lxxviii. 49; A. V. "evil angels") do only the bidding of God; they are the agents of His divine wrath. The evil spirit that troubled Saul (I Samuel 16:14 et seq.) may have been a demon, though the Masoretic text suggests the spirit was sent by God.

The king and queen of demons

In some rabbinic sources, the demons were believed to be under the dominion of a king or chief, either Asmodai (Targ. to Eccl. i. 13; Pes. 110a; Yer. Shek. 49b) or, in the older Haggadah, Samael ("the angel of death"), who kills by his deadly poison, and is called "chief of the devils." Occasionally a demon is called "Satan:" "Stand not in the way of an ox when coming from the pasture, for Satan dances between his horns" (Pes. 112b; compare B. Ḳ. 21a).

In Mesopotamian culture, Lilith was considered to be the queen of demons.[6] "When Adam, doing penance for his sin, separated from Eve for 130 years, he, by impure desire, caused the earth to be filled with demons, or shedim, lilin, and evil spirits" (Gen. R. xx.; 'Er. 18b.). This could have been the origins of the abominations that where part human part angelic creature; these where the offspring of incubuses.

Though the belief in demons was greatly encouraged and enlarged in Babylonia under the influence of the Zoroastrianism religion of the Persian Empire, demonology never became a mainstream feature of Jewish theology despite its use in Jewish mysticism. The reality of demons was never questioned by the Talmudists and late rabbis; most accepted their existence as a fact. Nor did most of the medieval thinkers question their reality. Only rationalists like Maimonides and Abraham ibn Ezra, clearly denied their existence. Their point of view eventually became the mainstream Jewish understanding.

In the New Testament and Christianity

In Christianity, demons are generally considered to be angels who fell from grace by rebelling against God. Some add that the sin of the angels was pride and disobedience. According to scripture, these were the sins that caused Satan's downfall (Ezek. 28). If this constitutes the true view, then one is to understand the words, "estate" or "principality" in Deuteronomy 32:8 and Jude 6 ("And the angels which kept not their first estate, but left their own habitation, he hath reserved in everlasting chains under darkness unto the judgment of the great day") as indicating that instead of being satisfied with the dignity once for all assigned to them under the Son of God, they aspired higher.

In the Gospel of Mark, Jesus casts out many demons, or evil spirits, from those who are afflicted with various ailments (such as epileptic seizures). The imagery is very clear: Jesus is far superior to the power of demons over the beings that they inhabit, and he is able to free these victims by commanding and casting out the demons, by binding them, and forbidding them to return. Jesus also apparently lends this power to some of his disciples, who rejoice at their new found ability to cast out most, but not all, demons.

By way of contrast, in the Book of Acts a group of Judaistic exorcists known as the sons of Sceva try to cast out a very powerful spirit without believing in or knowing Jesus, but failâwith disastrous consequences. However, Jesus himself never fails to vanquish a demon, no matter how powerful, and even defeats Satan in the wilderness (Gospel of Matthew).

There is a description in the Book of Revelation 12:7-17 of a battle between God's army and Satan's followers, and their subsequent expulsion from Heaven to earthâalthough this event is related as being foretold as taking place in the future. In Luke 10:18, it is mentioned that a power granted by Jesus to control demons made Satan "fall like lightning from heaven."

Some denominations also include, as demons, the "sons of God" described in Genesis who abandoned their posts in heaven to mate with human women on Earth before the Deluge (Genesis 6:2, 4, also see Nephilim). In the middle ages, these angels that mated with humans where called incubi.

The contemporary Roman Catholic Church unequivocally teaches that angels and demons are real personal beings, not just symbolic devices. The Catholic Church has a cadre of officially sanctioned exorcists who perform many exorcisms each year. The exorcists of the Catholic Church teach that demons attack humans continually but that afflicted persons can be effectively healed and protected either by the formal rite of exorcism, authorized to be performed only by bishops and those they designate, or by prayers of deliverance which any Christian can offer for themselves or others.

Among Evangelical Christians, demons are often identified with the attitudes and propensities that they cause in those whom they possess. Thus, a greedy man might be viewed as being possessed by the demon Greed, an envious woman by the demon Envy, an angry man by the demon Anger, and so on. Casting out these demons thus becomes equivalent to overcoming these bad attitudes and adopting their opposite; this is conceived of as possible through the power of Jesus Christ.

Christianization of the Greek "Daemon"

The Greek conception of a daemon appears in the works of Plato and many other ancient authors, but without the evil connotations that are apparent in the New Testament. The meaning of "daemon" is related to the idea of a spirit that inhabits a place, or that accompanies a person. A daemon could be either benevolent or malevolent. Augustine of Hippo's reading of Plotinus, in The City of God, is ambiguous as to whether daemons had become "demonized" by the early fifth century: "He [Plotinus] also states that the blessed are called in Greek eudaimones, because they are good souls, that is to say, good demons, confirming his opinion that the souls of men are demons."[7]

The "demonization" of the Hellenistic "daemon" into an malevolent spirit was no doubt assisted by the Jewish and Christian experience in pagan Rome. They saw among the cruelty of the Roman legions the manifestation of the Nephilim, the "fallen ones," a race of half-human giants who, according to Genesis 6:1-4, were conceived when a band of rebellious angels came down from Heaven and mated with mortal women. For the Greeks and Romans, however, their cultural heroes like Hercules and Anneas were precisely the offspring of such matings of the gods with women. For Jews under the Roman yoke in Palestine, or Christians suffering persecution in the Roman Empire, whose emperors were honored for being of the lineage of such a divine union, the cruel Roman authorities were identified with the Nephilim, and the gods of Greek and Roman mythology were identified with the fallen angels, that is, demons.[8]

In Christian mythology

Building upon the references to daemons in the New Testament, especially the visionary poetry of the Apocalypse of John, Christian writers of apocrypha from the second century onwards created a more complicated tapestry of beliefs about "demons."

According to apocryphal texts, when God created angels, he offered them the same choice he was to offer humanity: Follow, or be cast apart from him. Some angels chose not to follow God, instead choosing the path of evil. The fallen angels are the host of angels who later rebelled against God, headed by Lucifer, and later the 200 angels known as the Grigori, led by Semyazza, Azazel and other angelic chiefs, some of whom became the demons that were conjured by King Solomon and imprisoned in the brass vessel, the Goetia demons, descended to Earth and cohabited with the daughters of men.

The fall of the Adversary is portrayed in Ezekiel 28:12-19 and Isaiah 14:12-14. Christian writers built upon later Jewish traditions that the Adversary and the Adversary's host declared war with God, but that God's army, commanded by the archangel Michael, defeated the rebels. Their defeat was never in question, since God is by nature omnipotent, but Michael was given the honor of victory in the natural order; thus, the rise of Christian veneration of the archangel Michael, beginning at Monte Gargano in 493 C.E., reflects the full incorporation of demons into Christianity.

God then cast His enemies from Heaven to the abyss, into a prison called Hell (allusions to such a pit are made in the Book of Revelation, as pits of sulfur and fire) where all God's enemies should be sentenced to an eternal existence of pain and misery. This pain is not all physical; for their crimes, these angels, now called demons, would be deprived of the sight of God (2 Thessalonians 1:9), this being the worst possible punishment.

An indefinite time later (some biblical scholars believe that the angels fell sometime after the creation of living things), the Adversary and the other demons were allowed to tempt humans or induce them to sin by other means. The first time the Adversary did this was as a serpent in the earthly paradise called the "Garden of Eden," to tempt Eve, who became deceived by Satan's evil trickery. Eve then gave Adam some of the forbidden fruit and both of their eyes were opened to the knowledge of good and evil. Adam, however, was not deceived, instead choosing to eat of the fruit. 1 Timothy 2:14 mentions that Adam saw the deceit of the serpent and willingly ate of the fruit anyways.

Most Christian teachings hold that demons will be eternally punished and never reconciled with God. Other teachings postulate a Universal reconciliation, in which Satan, the fallen angels, and the souls of the dead that were condemned to Hell are reconciled with God. Origen, Jerome, and Gregory of Nyssa mentioned this possibility.

In Buddhism

In Buddhism, Mara is the demon who assaulted Gautama Buddha beneath the bodhi tree, using violence, sensory pleasure and mockery in an attempt to prevent the Buddha from attaining enlightenment. Within Buddhist cosmology, Mara personifies the "death" of the spiritual life. He is a tempter, distracting humans from practicing the Buddhist dharma through making the mundane seem alluring, or the negative seem positive. Buddhism utilizes the concept of Mara to represent and personify negative qualities found in the human ego and psyche. The stories associated with Mara remind Buddhists that such demonic forces can be tamed by controlling one's mind, cravings and attachments.

In Buddhist iconography, Mara is most often presented as a hideous demon, although sometimes he is depicted as an enormous elephant, cobra, or bull. When shown in a anthropomorphic (human) form, he is usually represented riding an elephant with additional tusks. Other popular scenes of Mara show his demon army attacking the Buddha, his daughters tempting the Buddha, or the flood that washes away those under Mara's command.

In Hinduism

There are various kinds of demons in Hinduism, including Asuras and Rakshasas.

Originally, the word Asura in the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda (the holy book of the Indo-Aryans) meant any supernatural spiritâgood or bad. Hence, even some of the devas (demigods), especially Varuna, have the epithet of Asura. In fact, since the /s/ of the Indic linguistic branch is cognate with the /h/ of the Early Iranian languages, the word Asura, representing a category of celestial beings, became the word Ahura (Mazda), the Supreme God of the monotheistic Zoroastrians. However, very soon, among the Indo-Aryans, Asura came to exclusively mean any of a race of anthropomorphic but hideous demons. All words such as Asura, Daitya (lit., sons of the demon-mother "Diti"), Rakshasa (lit. from "harm to be guarded against") are translated into English as demon. These demons are inherently evil and in a constant battle against the demigods. Hence, in Hindu iconography, the gods/demigods are shown to carry weapons to kill the asuras. Unlike Christianity, the demons are not the cause of the evil and unhappiness in present humankind (which occurs on the account of ignorance from recognizing one's true self). In later Puranic mythology, exceptions do occur in the demonic race to produce god-fearing Asuras, like Prahalada. Also, many Asuras are said to have been granted boons from one of the members of the Hindu trinity, viz., Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, when the latter had been appeased from penances. All Asuras, unlike the devas, are said to be mortals (though they vehemently wish to become immortal). Because of their mortality, they are excisable to the laws of Karma and rebirth. Many people metaphorically interpret these demons as manifestations of the ignoble passions in the human mind. The asuras live in Patala above Naraka (Hell), one of the three Lokas (worlds, dimensions, of existence). They are often depicted as ugly creatures. The Puranas describe many cosmic battles between asuras and devas for supremacy.

On the account of the Hindu theory of reincarnation and transmigration of souls according to one's Karma, other kinds of demons can also be enlisted. If a human does extremely horrible and sinful karma in his life, his soul will, upon his death, directly turn into an evil ghostly spirit, many kinds of which are recognized in the later Hindu texts. These demons could be Vetalas, Pishachas, Bhūtas etc.[9]

A Rakshasa (Sanskrit: राà¥à¤à¥à¤·à¤¸à¤, rÄÌká¹£asaḥ; alternately, raksasa or rakshas) is a demon or unrighteous spirit in Hindu mythology. Rakshasas are also called man-eaters ("Nri-chakshas," "Kravyads") or cannibals. A female rakshasa is called a rakshasi, and a female rakshasa in human form is a manushya-rakshasi.

According to the Ramayana, rakshasas were created from Brahma's foot; other sources claim they are descended from Pulastya, or from Khasa, or from Nirriti and Nirrita.[10] Legend has it that many rakshasas were particularly wicked humans in previous incarnations. Rakshasas are notorious for disturbing sacrifices, desecrating graves, harassing priests, possessing human beings, and so on.[11] Their fingernails are venomous, and they feed on human flesh and spoiled food. They are shape changers, illusionists, and magicians.

In pre-Islamic Arab culture

Pre-Islamic mythology does not discriminate between gods and demons. The jinn are considered as divinities of inferior rank, having many human attributes: They eat, drink, and procreate their kind, sometimes in conjunction with human beings; in which latter case the offspring shares the natures of both parents. The jinn smell and lick things, and have a liking for remnants of food. In eating, they use the left hand. Usually, they haunt waste and deserted places, especially the thickets where wild beasts gather. Cemeteries and dirty places are also favorite abodes. In appearing to people, jinn assume sometimes the forms of beasts and sometimes those of men.

Generally, jinn are peaceable and well disposed toward humans. Many pre-Islamic poets were believed to have been inspired by good jinn; and Muhammad himself was accused by his adversaries of having been inspired by jinn ("majnun"). However, there were also evil jinn, who contrived to injure people.

In Islam

Islam recognizes the existence of the jinn. Jinns are not the genies of modern lore, and they are not all evil, as demons are described in Christianity, but are seen as creatures that co-exist with humans. Angels cannot be demons according to Islamic beliefs because they have no free will to disobey Allah (God). According to Islamic, belief jinn live in communities much like humans, and unlike angels have the ability to choose between good or evil.

In Islam, the evil jinns are referred to as the shayÄtÄ«n, or devils, and Iblis (Satan) is their chief. Iblis was the first Jinn. According to Islam, the jinn are made of smokeless flame of fire (and humankind is made of clay.) According to the Qur'an, Iblis was once a pious servant of God (but not an angel), but when God created Adam from clay, Iblis became very jealous, arrogant, and disobeyed Allah (God). When Allah (God) commanded the angels to bow down before humans, Iblis, who held the position of an angel, refused.

Adam was the first man, and man was the greatest creation of God. Iblis could not stand this, and refused to acknowledge a creature made of "dirt" (man). God condemned Iblis to be punished after death eternally in the hellfire. God, thus, had created hell.

Iblis asked God if he may live to the last day and have the ability to mislead mankind and jinns, God said that Iblis may only mislead those whom God lets him. God then turned Iblis' countenance into horridness and condemned him to only have powers of trickery.

Adam and Eve (Hawwa in Arabic) were both together misled by Iblis into eating the forbidden fruit, and consequently fell from the garden of Eden to Earth.

In literature

French romance writer Jacques Cazotte (1719-1792) in The Devil in Love (Le Diable Amoureux, 1772) tells of a demon, or devil, who falls in love with an amateur human dabbler in the occult, and attempts, in the guise of a young woman, to win his affections. The book served as inspiration for, and is referred to within, Spanish author Arturo Perez-Reverte's novel The Club Dumas (El Club Dumas, 1993). Roman Polanski's 1999 adaptation of the novel, The Ninth Gate, stars Johnny Depp as rare book dealer Dean Corso. Corso is hired to compare versions of a book allegedly authored in league with the Devil, and finds himself aided by a demon, in the form of a young woman, in his adventure.

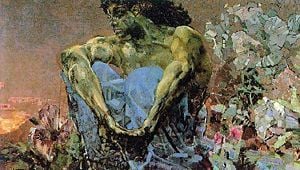

In Mikhail Lermontov's long poem (1840), the Demon makes love to the virgin Tamara in a scenic setting of the Caucasus mountains. Many classic books and plays feature demons, such as the Divine Comedy, Paradise Lost, and Faust.

Anton Rubinstein's lushly chromatic opera, The Demon (1875), based on the poem, "The Demon," by Lermontov, was delayed in its production because the censor attached to the Mariinsky Theatre felt that the libretto was sacrilegious.

L. Frank Baum's The Master Key features the Demon of Electricity.

In C.S. Lewis's The Screwtape Letters, Screwtape, a senior demon in Hell's hierarchy, writes a series of letters to his subordinate trainee, Wormwood, offering advice in the techniques of temptation of humans. Though fictional, it offers a plausible contemporary Christian viewpoint of the relationship of humans and demons.

J.R.R. Tolkien sometimes referred to the Balrogs of his Legendarium as "Demons."

Demons have permeated the culture of children's animated television series; they are used in comic books as powerful adversaries in horror, fantasy, and superhero stories. There are a handful of demons who fight for good for their own reasons like DC Comics' The Demon, Dark Horse Comics' Hellboy, and Marvel Comics' Ghost Rider.

In Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy, dæmons are the physical incarnation of a person's soul. Although they bear almost no resemblance to Christian demons, the word is pronounced the same.

In recent times, Fr. Gabriele Amorth, chief exorcist at the Vatican, has published two books on his experiences with Satan and many demons, entitled An Exorcist Tells His Story and An Exorcist: More Stories, published by Ignatius Press.

In the immensely popular novel and movie The Exorcist, by William Peter Blatty, a demon, possibly Satan himself, has taken possession of a young girl.

In recent Darren Shan novels, The Demonata series, demons feature as a large part of the books. They are portrayed as another set of sentient beings, struggling to exit their universe to destroy our world.

In modern Japanese manga and anime, there is the motif of a demon/human offspring referred to as hanyÅ, hanma, or hanki depending on the offspring's parentage.

Scientists occasionally invent hypothetical entities with special abilities as part of a thought experiment. These "demons" have abilities that are nearly limitless, but they are still subject to the physical laws being theorized about. Also, besides being part of thought experiments it also is relative to helping doctors treat patients.

Psychologist Wilhelm Wundt remarks that "among the activities attributed by myths all over the world to demons, the harmful predominate, so that in popular belief bad demons are clearly older than good ones."[12] The "good" demon in recent use is largely a literary device (e.g., Maxwell's demon), though references to good demons can be found in Apuleius, Hesiod and Shakespeare.[13] This belief of evil demons, can also be associated with the Christian belief that the first angels left from God with Lucifer. Psychologist have argued that the belief in demonic power is associated with the human psychology rather then a supernatural world."[14] Sigmund Freud develops on this idea and claims that the concept of demons was derived from the important relation of the living to the dead: "The fact that demons are always regarded as the spirits of those who have died recently shows better than anything the influence of mourning on the origin of the belief in demons."[15]

It has been asserted by some religious groups, demonologists, and paranormal investigators that demons can communicate with humans through the use of a Ouija board and that demonic oppression and possession can result from its use. Skeptics assert that the Ouija board's users move the game's planchette with their hands (consciously or unconsciously) and only appear to be communicating with spirits and that any resulting possession is purely psychosomatic. The original idea for the use of spirit boards was to contact spirits of dead humans and not evil spirits or demons. In the contemporary Western occultist tradition (perhaps epitomized by the work of Aleister Crowley), a demon, such as Choronzon, the "Demon of the Abyss," is a useful metaphor for certain inner psychological processes, though some may also regard it as an objectively real phenomenon.

Demons are also important or principal adversaries in numerous fantasy and horror-themed computer games.

Notes

- â Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, Demon. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- â Deliriums Realm, Shedim. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- â Pesachim, 112.

- â Bellum Judaeorum vii. 6, § 3.

- â "Antiquities" viii. 2, § 5.

- â Jewish Encyclopedia, Demonology. Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- â Augustine of Hippo, City of God, ch. 11.

- â Elaine Pagels, Adam, Eve, and the Serpent (New York: Random House, 1988), p. 38-45.

- â Vedic Knowledge, Planetarium. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- â Inside the Legend, Rakshasas. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- â Ibid.

- â Wundt, W. (1906). Mythus und Religion, Teil II (Völkerpsychologie, Band II). Leipzig.

- â www.sfsu.edu, Airy Demons:The Third World of Renaissance Pneumatology. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- â Freud, 65.

- â Sigmund Freud, Totem and Taboo (Oxford: Routledge, 1999). ISBN 0415191327

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bunce, Fredrick W., ed. An Encyclopaedia of Hindu Deities, Demi Gods, Godlings, Demons and Heroes. DK Print World, 2000. ISBN 978-8124601457

- Falk, Nancy E. Auer. "Mara." In The Encyclopedia of Religion, edited by Mircea Eliade. MacMillan, 1987. ISBN 0028971353

- Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo: Some Points of Agreement Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1950. ISBN 0393001431

- Ling, T.O. Buddhism and the Mythology of Evil. Allen and Unwin, 1962.

- Oppenheimer, Paul. Evil and the Demonic: A New Theory of Monstrous Behavior. New York: New York University Press, 1996. ISBN 0814761933

- Wundt, Wilhelm Maximilian. Mythus und Religion. Leipzig, Teil II Völkerpsychologie, Band II, 1906.

External links

All links retrieved January 28, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.