Imperial Japanese Navy

| Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) 大日本帝國海軍 (Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun) | |

|---|---|

The ensign of the Imperial Japanese Navy and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force. | |

| Active | 1869–1947 |

| Country | Empire of Japan |

| Allegiance | Empire of Japan |

| Branch | Combined Fleet Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service Imperial Japanese Navy Land Forces |

| Type | Navy |

| Engagements | First Sino-Japanese War Russo-Japanese War World War I World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Isoroku Yamamoto Togo Heihachiro Hiroyasu Fushimi and many others |

| Insignia | |

| Identification symbol |

Imperial Seal of Japan and Seal of the Imperial Japanese Navy |

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) (Kyūjitai: 大日本帝國海軍 Shinjitai: 大日本帝国海軍 Dai-Nippon Teikoku Kaigun ▶ or 日本海軍 Nippon Kaigun), officially Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire, also known as the Japanese Navy, was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1869 until 1947, when it was dissolved following Japan's constitutional renunciation of the use of force as a means of settling international disputes. The Imperial Japanese Navy had its origins in early interactions with nations on the Asian continent, beginning in the early medieval period and reaching a peak of activity during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, at a time of cultural exchange with European powers. Efforts to modernize the Japanese navy began under the late Tokugawa shogunate, and the Meiji Restoration in 1868 ushered in a period of rapid technological development and industrialization.

During World War I, a force of Japanese destroyers supported the Allies by protecting shipping in the Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean. In 1920, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the third largest navy in the world after the United States Navy and Royal Navy,[1]. Between the two World Wars, Japan took the lead in many areas of warship development. The Imperial Japanese Navy, supported by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, was a major force in the Pacific War. Though the Japanese strike on Pearl Harbor and sinking of the British warships Repulse and Prince of Wales in 1941 illustrated the effectiveness of air strikes against unprotected naval forces, the Imperial Japanese Navy clung to a "decisive battle" strategy, believing that the war would be decided by engagements between battleships. The largest battleships ever built, Yamato and Musashi, were sunk by air attacks long before coming within gun range of the American fleet, and the Japanese fleet was almost annihilated during the concluding days of World War II.

Origins

Japan's naval interaction with the Asian continent, involving transportation of troops between Korea and Japan, started at least from the beginning of the Kofun period in the third century.

Following Kubilai Khan’s attempts to invade Japan with Mongol and Chinese forces in 1274 and 1281, Japanese wakōu (pirates) became very active along the coast of the Chinese Empire.

In the sixteenth century, during the Warring States period, feudal Japanese rulers, vying with each other for supremacy, built vast coastal navies of several hundred ships. Japan may have developed one of the first ironclad warships, when Oda Nobunaga, a Japanese daimyo, had six iron-covered Oatakebune made in 1576.[2] In 1588, Toyotomi Hideyoshi organized a naval force which he used in the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592-1598).

Japan built its first large ocean-going warships in the beginning of the seventeenth century, following contacts with the Western nations during the Nanban trade period. In 1613, the Daimyo of Sendai, with the support of the Tokugawa Bakufu, built Date Maru, a 500-ton galleon-type ship that transported the Japanese embassy of Hasekura Tsunenaga to the Americas. From 1604, about 350 Red Seal ships, usually armed and incorporating some Western technologies, were also commissioned by the Bakufu, mainly for Southeast Asian trade.

Seclusion and Western studies

Beginning in 1640, for more than 200 years, the Tokugawa shogunate’s policy of "sakoku" (seclusion) forbade contacts with the West, eradicated Christianity in Japan, and prohibited the construction of ocean-going ships. Some contact with the West was maintained through the Dutch trading enclave of Dejima, allowing the transmission of Western technological and scientific knowledge. The study of Western sciences, called "rangaku," included cartography, optics and mechanical sciences. Full study of Western shipbuilding techniques resumed in the 1840s during the Late Tokugawa shogunate (Bakumatsu).

In 1852 and 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry sailed four of the United States Navy's newest steam warships into Edo Harbor, and initiated discussions that led to Japan’s ports becoming open to foreign trade. The 1854 Convention of Kanagawa which followed and the United States-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the "Harris Treaty" of 1858, which allowed the establishment of foreign concessions, included extra-territoriality for foreigners and minimal import taxes for foreign goods. Similar agreements had been made between the Great Britain and China during the previous decade. In the twentieth century these agreements began to be referred to as the "Unequal Treaties."

Shortly after Japan opened up to foreign influence, the Tokugawa shogunate initiated an active policy of assimilating Western naval technologies. In 1855, with Dutch assistance, the shogunate acquired its first steam warship, Kankō Maru, which was used for training, and established the Nagasaki Naval Training Center. In 1857, it acquired its first screw-driven steam warship, the Kanrin Maru. In 1859, the Naval Training Center was transferred to Tsukiji in Tokyo. Naval students such as the future Admiral Takeaki Enomoto (who studied in the Netherlands from 1862–1867), were sent to study in Western naval schools for several years, starting a tradition of foreign education for promising naval cadets. (Admirals Heihachiro Togo (1848 – 1934) and Isoroku Yamamoto (1884 – 1943) later studied abroad under this program.)

In 1863, Japan completed its first domestically-built steam warship, Chiyodagata. In 1865, the French naval engineer Léonce Verny was hired to build Japan's first modern naval arsenals, at Yokosuka in Kanagawa, and at Nagasaki. In 1867–1868, a British Naval mission headed by Captain Tracey[3] was sent to Japan to assist in the development of the Navy and to organize the naval school at Tsukiji.[4]

When the Tokugawa shogunate ended in 1867, the Tokugawa navy was already the largest of Eastern Asia, organized around eight Western-style steam warships and the flagship Kaiyō Maru. The navy fought against pro-imperial forces during the Boshin War, under the command of Admiral Enomoto. After the defeat of the forces of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the accomplishment of the Meiji Restoration, a part of the former Shogun's navy led by Admiral Enomoto Takeaki fled to the northern island of Ezo (now known as Hokkaidō), together with several thousand soldiers and a handful of French military advisors with their leader, Jules Brunet. Enomoto declared the “Ezo Republic” and petitioned the Imperial Court for official recognition, but his request was denied.[5] He was defeated, by the hastily-organized new Imperial navy, in Japan's first large-scale modern naval battle, the Naval Battle of Hakodate in 1869. Enomoto’s naval forces were superior, but the Imperial navy had taken delivery of the revolutionary French-built ironclad Kotetsu, originally ordered by the Tokugawa shogunate, and used it to win the engagement.

After 1868, the restored Meiji Emperor continued with modernization of industry and the military, to establish Japan as a world power in the eyes of the United States and Europe. On January 17, 1868, the Ministry of Military Affairs (兵部省, also known as the Army-Navy Ministry) was created, with Iwakura Tomomi, Shimazu Tadayoshi and Prince Komatsu-no-miya Akihito as the First Secretaries.

On March 26, 1868, the first Japanese Naval Review was held in Osaka Bay. Six ships from the private navies of Saga, Chōshū, Satsuma, Kurume, Kumamoto, and Hiroshima participated. The total tonnage of these ships was 2252 tons, far smaller than the tonnage of the single foreign vessel (from the French Navy) that also participated. The following year, in July, 1869, the Imperial Japanese Navy was formally established, two months after the last combat of the Boshin War.

The private navies were abolished, and their 11 ships were added to the seven surviving vessels of the defunct Tokugawa bakufu navy, to form the core of the new Imperial Japanese Navy. In February 1872 the Ministry of Military Affairs was replaced by a separate Army Ministry (陸軍省) and Navy Ministry (海軍省). In October 1873, Katsu Kaishu became Navy Minister. The new government drafted an ambitious plan to create a Navy with 200 ships, organized into ten fleets; it was abandoned within a year due to lack of resources.

British support

During the 1870s and 1880s, the Imperial Japanese Navy remained an essentially coastal defense force, although the Meiji government continued to modernize it. Jho Sho Maru (soon renamed Ryūjō Maru) commissioned by Thomas Glover, was launched at Aberdeen, Scotland on March 27, 1869. In 1870, an Imperial decree dictated that Britain's Royal Navy should be the model for development, instead of the navy of the Netherlands.[6]

From September, 1870, the English Lieutenant Horse, a former gunnery instructor for the Saga fief during the Bakumatsu period, was put in charge of gunnery practice aboard the Ryūjō.[7] In 1871, the Ministry resolved to send 16 trainees abroad for training in naval sciences (14 to Great Britain, two to the United States), among which was Togo Heihachiro.[8] A 34-member British naval mission, headed by Comdr. Archibald Douglas, visited Japan in 1873 and stayed for two years.[9] In 1879, Commander L. P. Willan was hired to train naval cadets.

First interventions abroad (Taiwan 1874, Korea 1875–76)

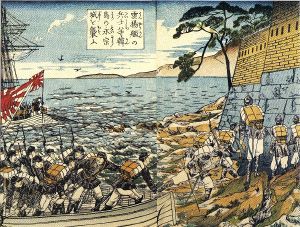

During 1873, a plan to invade the Korean peninsula (the Seikanron proposal, made by Saigo Takamori) was dropped by the central government in Tokyo. In 1874, the new Imperial Japanese Navy and Imperial Japanese Army made their first foray abroad, the Taiwan Expedition of 1874, to punish the Paiwan aborigines on the southwestern tip of Taiwan for beheading 54 crew members of a shipwrecked Okinawan merchant vessel.

Paiwanese casualties numbered about 30; of the 3,600 Japanese soldiers, 531 died of disease and 12 were killed in battle. Japanese forces withdrew from Taiwan after the Qing government agreed to an indemnity of 500,000 Kuping taels. The expedition forced China to recognize Japanese sovereignty over Okinawa (Ryūkyū Islands), and mollified those within the Meiji government who were pushing for a more aggressive foreign policy.

Various interventions in the Korean Peninsula occurred in 1875–1876, starting with the Ganghwa Island incident (江華島事件) provoked by the Japanese gunboat Unyo, that led to the dispatch of a large force of the Imperial Japanese Navy. The resulting Treaty of Ganghwa officially opened Korea to foreign trade, it was Japan's first use of Western-style intervention and “unequal treaties.”

The Saga Rebellion (1874), and especially the Satsuma Rebellion (1877), forced the Imperial government to focus on land warfare. Naval policy, expressed by the slogan Shusei Kokubō (Jp:守勢国防, "Static Defense"), concentrated on coastal defenses and the maintenance of a standing army (established with the assistance of the second French Military Mission to Japan (1872-1880)), and a coastal Navy. The military was organized under a policy of Rikushu Kaijū (Jp:陸主海従; "Army first, Navy second").

In 1878, the Japanese cruiser Seiki sailed to Europe with an entirely Japanese crew.[10]

Further modernization (1870s)

Ships such as the Japanese ironclad warship Fusō, Japanese corvette Kongō (1877), and the Japanese corvette Hiei (1877) were built in British shipyards specifically for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Private ship-building companies such as Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries and Kawasaki Heavy Industries, Ltd. also emerged during the 1870s.

In 1883, two large warships, the Naniwa and the Takachiho, were ordered from British shipyards. These were 3,650-ton ships, capable of speeds up to 18 knots (33 km/h), and armed with two- to three-inch deck armor and two 10.2-in (260 mm) Krupp guns. They were designed by naval architect Sasō Sachū along the lines of the Elswick class of protected cruisers, but with superior specifications. China simultaneously purchased two German-built battleships of 7,335 tons, (Ting Yüan and Chen-Yüan). Unable to confront the Chinese fleet with only two modern cruisers, Japan turned to the French for assistance in building a large, modern fleet that could prevail in a conflict with China.

Influence of the French "Jeune Ecole" (1880s)

During the 1880s, France’s "Jeune Ecole" ("young school") strategy, favoring small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, against bigger units, had the greatest influence on Japan. The Minister of the Japanese Navy (海軍卿) at that time was Enomoto Takeaki (Navy Minister 1880–1885), a former ally of the French during the Boshin War.

The Meiji government issued its First Naval Expansion Bill in 1882, requiring the construction of 48 warships, of which 22 were to be torpedo boats. The naval successes of the French Navy against China in the Sino-French War of 1883–1885 seemed to validate the potential of torpedo boats, an approach which suited the limited resources of Japan. In 1885, the new Navy slogan became Kaikoku Nippon (Jp:海国日本; "Maritime Japan").

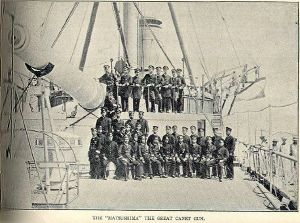

In 1885, the leading French Navy engineer Emile Bertin was hired for four years to reinforce the Japanese Navy, and to direct the construction of the arsenals of Kure, Hiroshima, and Sasebo, Nagasaki. He developed the Sanseikan class of cruisers; three units featuring a single powerful main gun, the 12.6 in (320 mm) Canet gun. Altogether, Bertin supervised the building of more than 20 war ships, which helped establish the first truly modern Japanese naval force. of Japan. Some of the ships were imported, but some were built domestically at the arsenal of Yokosuka, Kanagawa, giving Japanese shipyards the experience needed to build larger vessels.

The new Imperial Japanese Navy constituted:

- 3 cruisers: the 4,700 ton Matsushima and Itsukushima, built in France, and the Hashidate, built at Yokosuka.

- 3 coastal warships of 4,278 tons.

- 2 small cruisers: the Chiyoda, a small cruiser of 2,439 tons built in Britain, and the Yaeyama, 1800 tons, built at Yokosuka.

- 1 frigate, the 1600 ton Takao, built at Yokosuka.

- 1 destroyer: the 726 ton Chishima, built in France.

- 16 torpedo boats of 54 tons each, built in France by the Companie du Creusot in 1888, and assembled in Japan.

During this period, Japan embraced "the revolutionary new technologies embodied in torpedoes, torpedo-boats and mines, of which the French at the time were probably the world's best exponents".[11] Japan acquired its first torpedoes in 1884, and established a "Torpedo Training Center" at Yokosuka in 1886.

These ships, ordered during the fiscal years 1885 and 1886, were the last major orders placed with France. The unexplained sinking of the Japanese cruiser Unebi en route' from France to Japan in December, 1886, created diplomatic friction and doubts about the integrity of French designs.

British shipbuilding

In 1877, Japan placed an order with Britain for a revolutionary torpedo boat, Kotaka (considered the first effective design of a destroyer),[12]. Japan also purchased the cruiser Yoshino, built at the Armstrong Whitworth works in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, the fastest cruiser in the world at the time of her launch in 1892. In 1889, Japan ordered the Clyde-built Chiyoda, which defined the type for armored cruisers.[13]

From 1882 until the visit of the French Military Mission to Japan in 1918-1919, the Imperial Japanese Navy stopped relying on foreign instructors altogether. In 1886, Japan manufactured its own prismatic powder, and in 1892 a Japanese officer invented a powerful explosive, the Shimose powder.[14]

Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

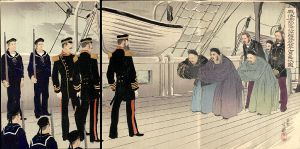

While Japan continued the modernization of its navy, China was also building a powerful modern fleet with foreign, especially German, assistance, and the pressure was building between the two countries over control of Korea. The Sino-Japanese war was officially declared on August 1, 1894, though some naval fighting had already taken place.

The Japanese navy devastated Qing China's Beiyang Fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River at the Battle of Yalu River on September 17, 1894, in which the Chinese fleet lost eight out of 12 warships. Although Japan was victorious, the Chinese Navy’s two large German-made battleships remained almost impervious to Japanese guns, highlighting the need for bigger capital ships in the Japanese Navy (Ting Yuan was finally sunk by torpedoes, and Chen-Yuan was captured with little damage). The next step of the Imperial Japanese Navy's expansion involved a combination of heavily armed large warships, with smaller and innovative offensive units capable of aggressive tactics.

As a result of the conflict, Taiwan and the Pescadores Islands were transferred to Japan under the Treaty of Shimonoseki (April 17th, 1895). The Imperial Japanese Navy took possession of the islands and quelled opposition movements between March and October, 1895, and the islands remained a Japanese colony until 1945. Japan also obtained the Liaodong Peninsula, although Russia forced its return to China, and took possession of it soon afterward.

Suppression of the Boxer Rebellion (1900)

The Imperial Japanese Navy intervened in China again in 1900, by participating together with Western powers to the suppress the Chinese Boxer Rebellion. Among the intervening nations, the Imperial Japanese Navy supplied the largest number of warships (18 out of a total of 50) and delivered the largest contingent of troops (20,840 Imperial Japanese Army and Navy soldiers, out of total of 54,000). This experience gave the Japanese a first-hand understanding of Western methods of warfare.

Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905)

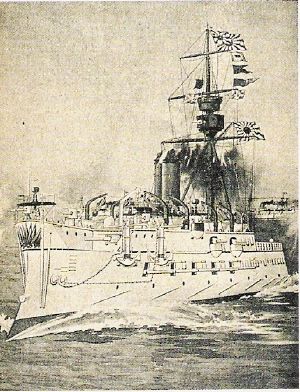

Following the Sino-Japanese War, and the humiliation of the forced return of the Liaotung peninsula to China under Russian pressure (the "Triple Intervention"), Japan began to build up its military strength in preparation for further confrontations. Japan promulgated a ten-year naval build-up program, under the slogan "Perseverance and determination" (Jp:臥薪嘗胆, Gashinshōtan), in which it commissioned 109 warships, a total of 200,000 tons; and increased its Navy personnel from 15,100 to 40,800. The new fleet consisted of:

- 6 battleships (all British-built)

- 8 armored cruisers (4 British-, 2 Italian-, 1 German-built Yakumo, and 1 French-built Azuma)

- 9 cruisers (5 Japanese-, 2 British- and 2 U.S.-built)

- 24 destroyers (16 British- and 8 Japanese-built)

- 63 torpedo boats (26 German-, 10 British-, 17 French-, and 10 Japanese-built)

One of these battleships, Mikasa, the most advanced ship of her time,[16] was ordered from the Vickers shipyard in the United Kingdom at the end of 1898, for delivery to Japan in 1902. The twin screw commercial steamer Aki-Maru was built for Nippon Yusen Kaisha by the Mitsubishi Dockyard & Engine Works, Nagasaki, Japan. The Imperial Japanese cruiser Chitose was built at the Union Iron Works in San Francisco, California.

These dispositions culminated with the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905). At the Battle of Tsushima, Admiral Togo aboard Mikasa led the combined Japanese fleet into the decisive engagement of the war.[17] The Russian fleet was almost completely annihilated: out of 38 Russian ships, 21 were sunk, 7 captured, 6 disarmed, 4,545 Russian servicemen died and 6,106 were taken prisoner. The Japanese lost only 116 men and three torpedo boats. These victories broke Russian strength in East Asia, and weakened Russian morale, triggering mutinies in the Russian Navy at Sevastopol, Vladivostok and Kronstadt, and the Potemkin rising that contributed to the Russian Revolution of 1905.

During the Russo-Japanese war, Japan made concerted efforts to develop and build a fleet of submarines. Submarines, which had only recently become operational military engines, were considered to be special weapons of considerable potential. The Imperial Japanese Navy acquired its first submarines in 1905 from the United States Electric Boat Company, barely four years after the U.S. Navy had commissioned its own first submarine, USS Holland. The ships were John Philip Holland designs, and were developed under the supervision of Arthur L. Busch, a representative of Electric Boat, who had built the USS Holland. Five submarines were shipped in kit form to Japan in October, 1904, and assembled as hulls No. 1 through 5 by Busch at the Yokosuka Naval Yard. The submarines became operational at the end of 1905.

The 1906 battleship Satsuma was built in Japan, with about 80 percent of its parts imported from Britain; but the next battleship class, the 1910 Kawachi, was built with only 20 percent imported parts.

Japan continued in its efforts to build up a strong national naval industry. Following a strategy of "Copy, improve, innovate",[18] foreign ships of various designs were analyzed in depth, their specifications often improved on, and were then purchased in pairs so that comparative testing and improvement could be done. Over the years, the importation of whole classes of ships was replaced by local assembly, and then by complete local production, starting with the smallest ships, such as torpedo boats and cruisers in the 1880s, and finishing with whole battleships in the early 1900s. The last major purchase was the battlecruiser Kongō, purchased from the Vickers shipyard in 1913. By 1918, Japan met world standards in every aspect of shipbuilding technology.[19]

Immediately after the Battle of Tsushima, the Imperial Japanese Navy, under the influence of the naval theoretician Satō Tetsutarō, adopted a policy of building a fleet for hypothetical combat against the United States Navy. Satō called for a battle fleet at least 70 percent as strong as that of the U.S. In 1907, the official policy of the Navy became an 'eight-eight fleet' of eight modern battleships and eight battlecruisers, but financial constraints prevented this ideal ever becoming a reality.[20]

By 1920, the Imperial Japanese Navy was the world's third largest navy, and was a leader in many aspects of naval development:

- The Japanese Navy was the first navy in the world to use wireless telegraphy in combat (following its 1897 invention by Marconi), at the 1905 Battle of Tsushima.[21]

- In 1905, Japan began building the battleship Satsuma, at the time the largest warship in the world by displacement, and the first ship in the world to be designed, ordered and laid down as an "all-big-gun" battleship, about one year before HMS Dreadnought (1906). She was, however, completed after the Dreadnought, with mixed-caliber guns due to a lack of 12 inch guns.[22]

World War I

Japan entered World War I on the side of the Allies, against Imperial Germany and Austria-Hungary, as a natural prolongation of the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance.

In the Battle of Tsingtao, the Japanese Navy seized the German naval base of Tsingtao. During the battle, beginning on September 5, 1914, Wakamiya conducted the world's first sea-launched air strikes.[23] from Kiaochow Bay.[24] Four Maurice Farman seaplanes bombarded German land targets (communication centers and command centers) and damaged a German minelayer in the Tsingtao peninsula from September to November 6, 1914, when the Germans surrendered.[25]

Concurrently, a battle group was sent to the central Pacific in August and September of 1914 to pursue the German East Asiatic squadron, which then moved into the Southern Atlantic, where it encountered British naval forces and was destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. Japan seized former German possessions in Micronesia (the Mariana Islands, excluding Guam); the Caroline Islands; and the Marshall Islands), which remained Japanese colonies until the end of World War II, under the League of Nations' South Pacific Mandate.

Hard-pressed in Europe, where she had only a narrow margin of superiority against Germany, Britain had requested, but was denied, the loan of Japan's four newest Kongō-class battleships (Kongō, Hiei, Haruna, and Kirishima), the first ships in the world to be equipped with 14-inch (356 mm) guns, and the most formidable capital ships in the world at the time.[26] British battleships with 15-inch-guns came into use during the war.

In March, 1917, after a further request for support from Britain, and the advent of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany, the Imperial Japanese Navy sent a special force of destroyers to the Mediterranean. This force, consisting of one armored cruiser, Akashi, as flotilla leader, and eight of the Navy's newest destroyers (Ume, Kusunoki, Kaede, Katsura, Kashiwa, Matsu, Matsu, Sugi, and Sakaki), under Admiral Satō Kōzō, was based in Malta and efficiently protected Allied shipping between Marseille, Taranto, and ports in Egypt until the end of the war. In June, Akashi was replaced by Izumo, and four more destroyers were added (Kashi, Hinoki, Momo, and Yanagi). They were later joined by the cruiser Nisshin. By the end of the war, the Japanese had escorted 788 Allied transports. One destroyer, Sakaki, was torpedoed by an Austrian submarine with the loss of 59 officers and men.

In 1918, ships such as Azuma were assigned to convoy escort in the Indian Ocean between Singapore and the Suez Canal as part of Japan’s contribution to the war effort under the Anglo-Japanese alliance.

After the conflict, seven German submarines, allotted to the Japanese Navy as spoils of war, were brought to Japan and analyzed, contributing significantly to the development of the Japanese submarine industry.[27]

Interwar years

In the years before World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy began to structure itself specifically to fight the United States. A long stretch of militaristic expansion and the start of the Second Sino-Japanese war in 1937 had alienated the United States, which was seen by Japan as a rival.

Before and during World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy faced considerable challenges. [28] Japan, like Britain, was almost entirely dependent on foreign resources to supply its economy. To achieve Japan’s expansionist policies, the Imperial Japanese Navy had to secure and protect distant sources of raw material (especially Southeast Asian oil and raw materials), controlled by foreign countries (Britain, France, and the Netherlands). To achieve this goal, Japan built large warships capable of long range.

This contradicted Japan's doctrine of "decisive battle" (艦隊決戦, Kantai Kessen, which did not require long range warships),[29] in which the Imperial Japanese Navy would allow the U.S. fleet to sail across the Pacific, while using submarines to gradually pick off battleships, and after inflicting this attrition, would engage the weakened U.S. Navy in a "decisive battle area" near Japan.[30] Every major navy before World War II subscribed to the theory of Alfred T. Mahan, that wars would be decided by engagements between opposing surface fleets[31], as they had been for over 300 years. This theory was the reason for Japan's demand for a 70 percent ratio of ships to the U.S. and Britain (10:10:7) at the Washington Naval Conference, which would give Japan naval superiority in the "decisive battle area," and for the U.S.'s insistence on a 60 percent ratio, which meant parity.[32] Japan clung to this theory even after it had been demonstrated to be obsolete.

To compensate for its numerical and industrial inferiority, the Imperial Japanese Navy actively pursued technical superiority (fewer, but faster, more powerful, ships), superior quality (better training), and aggressive tactics. Japan relied on daring and speedy attacks to overwhelm the enemy, a strategy that had succeeded in previous conflicts, but failed to account for the fact its opponents in the Pacific War did not face the same political and geographical constraints as in previous wars.[33]

Between the two World Wars, Japan took the lead in many areas of warship development:

- In 1921 it launched the Hōshō, the first purpose-designed aircraft carrier in the world to be completed,[34] and subsequently developed a fleet of aircraft carriers second to none.

- The Imperial Navy was the first navy in the world to mount 14-in (356 mm) guns (in Kongō), 16-in (406 mm) guns (in Nagato), and the only Navy ever to mount 18.1-in (460 mm) guns (in the Yamato-class ships).[35]

- In 1928, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched the innovative Fubuki-class destroyer, introducing enclosed dual 5-inch turrets capable of anti-aircraft fire. The new destroyer design was soon emulated by other navies. The Fubukis also featured the first torpedo tubes enclosed in splinterproof turrets.[36]

- Japan developed the 24-inch (610 mm) oxygen-fueled Type 93 torpedo, generally recognized as the best torpedo in the world, until the end of World War II.[37]

By 1921, Japan's naval expenditure had reached nearly 32 percent of the national budget. By 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy possessed 10 battleships, 10 aircraft carriers, 38 cruisers (heavy and light), 112 destroyers, 65 submarines, and various auxiliary ships.[38]

Japan continued to solicit foreign expertise in areas such as naval aviation. In 1918, Japan invited the French Military Mission to Japan (1918-1919), composed of 50 members and equipped with several of the newest types of airplanes, to establish the fundamentals of Japanese naval aviation (the planes were several Salmson 2A2, Nieuport, Spad XIII, and two Breguet XIV, as well as Caquot dirigibles). In 1921, Japan hosted, for a year and a half, the Sempill Mission, a group of British instructors who trained and advised the Imperial Japanese Navy on several new aircraft such as the Gloster Sparrowhawk, and on various techniques such as torpedo bombing and flight control.

During the years before World War II, military strategists debated whether the Navy should be organized around powerful battleships that would ultimately be able to defeat American battleships in Japanese waters, or around aircraft carriers. Neither concept prevailed, and both lines of ships were developed. A consistent weakness of Japanese warship development was the tendency to incorporate too much armament, and too much engine power, relative to ship size (a side-effect of the Washington Treaty), to the detriment of stability, protection, and structural strength.[39]

World War II

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Navy was administered by the Ministry of the Navy of Japan and controlled by the Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff at Imperial General Headquarters. In order to match the numerical superiority of the American navy, the Imperial Japanese Navy had devoted considerable resources to creating a force superior in quality to any navy at the time. At the beginning of World War II, the Japanese navy was the third largest, and probably the most sophisticated, in the world.[40] Favoring speed and aggressive tactics, Japan did not invest significantly in defensive organization. Particularly under-invested in antisubmarine warfare (both escort ships and escort aircraft carriers), and in the specialized training and organization to support it, Japan never managed to adequately protect her long shipping lines against enemy submarines.[41]

During the first part of the hostilities, the Imperial Japanese Navy enjoyed resounding success. American forces ultimately gained the upper hand through technological upgrades to air and naval forces, and a vastly stronger industrial output. Japan's reluctance to use its submarine fleet for raiding commercial shipping lines, and failure to secure its communications, hastened defeat. During the last phase of the war, the Imperial Japanese Navy resorted to a series of desperate measures, including the Special Attack Units popularly known as kamikaze.

Battleships

Japan’s military government continued to attach considerable prestige to battleships and endeavored to build the largest and most powerful ships of the period. Yamato, the largest and most heavily-armed battleship in history, was launched in 1941.

The last battleship duels occurred during the second half of World War II. In the Battle of Guadalcanal on November 15, 1942, the United States battleships South Dakota and Washington fought and destroyed the Japanese battleship Kirishima. In the Battle of Leyte Gulf on October 25, 1944, six battleships, led by Admiral Jesse Oldendorf of the U.S. 7th Fleet, fired upon and claimed credit for sinking Admiral Shoji Nishimura's battleships Yamashiro and Fusō during the Battle of Surigao Strait; in fact, both battleships were fatally crippled by destroyer attacks before being brought under fire by Oldendorf's battleships.

The battle off Samar on October 25, 1944, the central action of the Battle of Leyte Gulf demonstrated that battleships could still be useful. Only the indecision of Admiral Takeo Kurita and the defensive battle of American destroyers and destroyer escorts saved the American aircraft carriers of "Taffy 3" from being destroyed by the gunfire of Yamato, Kongō, Haruna, and Nagato and their cruiser escort. The Americans lost only USS Gambier Bay, along with two destroyers and one destroyer escort, in this action.

The development of air power ended the sovereignty of the battleship. Battleships in the Pacific primarily performed shore bombardment and anti-aircraft defense for the carriers. Yamato and Musashi were sunk by air attacks long before coming in gun range of the American fleet. As a result, plans for even larger battleships, such as the Japanese Super Yamato class, were canceled.

Aircraft carriers

In the 1920s, the Kaga (originally designed as a battleship) and a similar ship, the Akagi (originally designed as a battlecruiser) were converted to aircraft carriers to satisfy the terms of the Washington Naval Treaty.

From 1935-1938, Akagi and Kaga received extensive rebuilds to improve their aircraft handling capacity. Japan put particular emphasis on aircraft carriers. The Imperial Japanese Navy started the Pacific War with 10 aircraft carriers, the largest and most modern carrier fleet in the world at that time. At the beginning of hostilities, only three of the seven American aircraft carriers were operating in the Pacific; and of eight British aircraft carriers, only one operated in the Indian Ocean. The Imperial Japanese Navy 's two Shōkaku-class carriers were superior to any aircraft carrier in the world, until the wartime appearance of the American Essex-class.[42] A large number of the Japanese carriers were of small size, however, in accordance with the limitations placed upon the Navy by the London and Washington Naval Conferences.

Following the Battle of Midway, in which four Japanese fleet carriers were sunk, the Japanese Navy suddenly found itself short of fleet carriers (as well as trained aircrews), and initiated an ambitious set of projects to convert commercial and military vessels into escort carriers, such as the Hiyō. The Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano was a conversion of an incomplete Yamato-class super battleship, and became the largest-displacement carrier of World War II. The Imperial Japanese Navy also began to build a number of fleet carriers; most of these projects were not completed by the end of the war except for the Taihō, the first and only Japanese carrier with an armored flight deck and first to incorporate a closed hurricane bow.

Japan began World War II with a highly competent naval air force, designed around some of the best airplanes in the world: the Zero was considered the best carrier aircraft at the beginning of the war, the Mitsubishi G3M bomber was remarkable for its range and speed, and the Kawanishi H8K was world's best flying boat.[43] The Japanese pilot corps at the beginning of the war were highly trained compared to their contemporaries around the world, due to their frontline experience in the Sino-Japanese War.[44] The Navy also had a competent tactical bombing force organized around the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M bombers, which surprised the world by being the first planes to sink enemy capital ships underway, claiming battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse.

As the war dragged on, the Allies found weaknesses in Japanese naval aviation. Though most Japanese aircraft were characterized by great operating ranges, they had little defensive armament and armor. The more numerous, heavily armed and armored American aircraft developed techniques that minimized the advantages of the Japanese aircraft. Although there were delays in engine development, several new competitive designs were developed during the war, but industrial weaknesses, lack of raw materials, and disorganization due to Allied bombing raids, hampered their mass-production. The Imperial Japanese Navy did not have an efficient process for rapid training of aviators; two years of training were usually considered necessary for a carrier flyer. Following their initial successes in the Pacific campaign, the Japanese were forced to replace the seasoned pilots lost through attrition with young, inexperienced flyers. The inexperience of later Imperial Japanese Navy pilots was especially evident during the Battle of the Philippine Sea, when their aircraft were shot down in droves by the American naval pilots in what the Americans later called the "Great Marianas Turkey Shoot." Following the Battle of Leyte Gulf, the Japanese Navy increasingly deployed aircraft as kamikaze.

Towards the end of the conflict, several effective new planes were designed, such as the 1943 Shiden, but the planes were produced too late and in insufficient numbers (415 units for the Shiden) to affect the outcome of the war. Radical new designs were also developed, such as the canard design Shinden, and especially jet-powered aircraft such as the Nakajima Kikka and the rocket-propelled Mitsubishi J8M. These jet designs were partially based on technology received from Nazi Germany, usually in the form of a few drawings (Kikka was based on the Messerschmitt Me 262 and the J8M on the Messerschmitt Me 163), so that Japanese manufacturers had to carry out the final engineering. These new developments occurred too late to influence the outcome of the war; the Kikka only flew once before the end of World War II.

Submarines

Japan had by far the most varied fleet of submarines of World War II, including manned torpedoes (Kaiten), midget submarines (Ko-hyoteki, Kairyu), medium-range submarines, purpose-built supply submarines (many for use by the Army), long-range fleet submarines (many of which carried an aircraft), submarines with the highest submerged speeds of the conflict (Senkou I-200), and submarines that could carry multiple bombers (World War II's largest submarine, the Sentoku I-400). These submarines were also equipped with the most advanced torpedo of World War II, the Type 95 torpedo, a 21" (533 mm) version of the famous 24" (61cm) Type 91.

A plane from one such long-range fleet submarine, I-25, conducted the only aerial bombing attack in history on the continental United States, when Warrant Flying Officer Nobuo Fujita attempted to start massive forest fires in the Pacific Northwest outside the town of Brookings, Oregon on September 9, 1942. Other submarines such as the I-30, I-8, I-34, I-29, and I-52, undertook trans-oceanic missions to German-occupied Europe, in one case flying a Japanese seaplane over France in a propaganda coup.[45] In May 1942, Type A midget submarines were used in the attack on Sydney Harbor, and the Battle of Madagascar.

Despite their technical refinements, Japanese submarines were relatively unsuccessful. They were often used in offensive roles against warships which were fast, maneuverable and well-defended compared to merchant ships. In 1942, Japanese submarines sank two fleet carriers, one cruiser, and a few destroyers and other warships, and damaged several others. They were not able to sustain these results afterwards, when Allied fleets were reinforced and began using more effective anti-submarine tactics. By the end of the war, submarines were often used to transport supplies to island garrisons. During the war, Japan sank about one million tons of merchant shipping (184 ships), compared to 1.5 million tons for Britain (493 ships), 4.65 million tons for the US (1,079 ships)[46] and 14.3 million tons for Germany (2,840 ships).

Early models were not easily maneuverable under water, could not dive very deep, and lacked radar. Later in the war, units fitted with radar were, in some instances, sunk when U.S. radar sets detected their emissions. USS Batfish (SS-310) sank three such submarines in the span of four days. After the end of the conflict, several of Japan's most original submarines were sent to Hawaii for inspection in "Operation Road's End" (I-400, I-401, I-201, and I-203) before being scuttled by the U.S. Navy in 1946 when the oviets demanded equal access to the submarines.

Special Attack Units

At the end of World War II, numerous Special Attack Units (Japanese: 特別攻撃隊, tokubetsu kōgeki tai, also abbreviated to 特攻隊, tokkōtai) were developed for suicide missions, in a desperate move to compensate for the annihilation of the main fleet. These units included Kamikaze ("Divine Wind") bombers, Shinyo ("Sea Quake") suicide boats, Kairyu ("Sea Dragon") suicide midget submarines, Kaiten ("Turn of Heaven") suicide torpedoes, and Fukuryu ("Crouching Dragon") suicide scuba divers, who would swim under boats and use explosives mounted on bamboo poles to destroy both the boat and themselves. Kamikaze planes were particularly effective during the defense of Okinawa, in which 1,465 planes were expended to damage around 250 American warships.

A considerable number of Special Attack Units, with the potential to destroy or damage thousands of enemy warships, were prepared and stored in coastal hideouts for the last defense of the home islands.

Imperial Japanese Navy Land Forces of World War II originated with the Special Naval Landing Forces, and eventually consisted of the following:

- Special Naval Landing Force or Rikusentai or kaigun rikusentai or Tokubetsu Rikusentai: the Japanese Marines

- The Base Force or Tokubetsu Konkyochitai, which provided services, primarily security, to naval facilities

- Defence units or Bobitai or Boei-han: detachments of 200 to 400 men.

- Guard forces or Keibitai: detachments of 200–500 men who provide security to Imperial Japanese Navy facilities

- Pioneers or Setsueitai who built naval facilities, including airstrips, on remote islands.

- Naval Civil Engineering and Construction Units, or Kaigun Kenchiku Shisetsu Butai

- The Naval Communications Units or Tsushintai of 600–1,000 men, who provided basic naval communications and handled encryption and decryption.

- The Tokeitai Navy military police units, part of the naval intelligence armed branch, with military police regular functions in naval installations and occupied territories; they also worked with the Imperial Japanese Army's Kempeitai military police, the Keishicho civil police and Tokko secret units in security and intelligence services.

Self-Defense Forces

Following Japan's surrender to the Allies at the conclusion of World War II, and Japan's subsequent occupation, Japan's entire imperial military was dissolved in the new 1947 constitution which states, "The Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as a means of settling international disputes." Japan's current navy falls under the umbrella of the Japan Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) as the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF).

See also

Notes

- ↑ David C. Evans & Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 0870211927)

- ↑ THE FIRST IRONCLADS In Japanese: [1], Also in English: samurai-archives.com. quote: "Iron clad ships, however, were not new to Japan and Hideyoshi; Oda Nobunaga, in fact, had many iron clad ships in his fleet." (referring to the anteriority of Japanese ironclads (1578) to the Korean Turtle ships (1592)). In Western sources, Japanese ironclads are described in C. R. Boxer, The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650. (original 1951; reprint ed. Manchester: Carcanet Press Ltd, 1993. ISBN 1857540352), 122, quoting the account of the Italian Jesuit Organtino visiting Japan in 1578. Nobunaga's ironclad fleet is also described in George Samson. A History of Japan, 1334–1615. (original 1958) (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1963. ISBN 0804705259), 309. Korea's "ironclad Turtle ships" were invented by Admiral Yi Sun-sin, and are first documented in 1592. Incidentally, Korea's iron plates only covered the roof (to prevent intrusion), and not the sides of their ships. The first Western ironclads date to 1859 with the French FS La Gloire (1858-1883), quoted in Robert Gardiner and Andrew Lambert, (eds.) Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. (Conway's History of the Ship) (Naval Institute Press, 1992; reprint ed. 2001. ISBN 0785814132).

- ↑ Rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 30, 2008

- ↑ Described in Christian Polak. Soie et lumières: l'âge d'or des échanges franco-japonais. (Kinu to hikari: shirarezaru Nichi-Futsu kōryū 100-nen no rekishi (Edo jidai-1950-nendai). (Tōkyō: Ashetto Fujin Gahōsha, 2002. ISBN 4573062106) in a parallel to the French Military Mission to Japan (1867-1868) for the Army.

- ↑ Romulus Hillsborough. Shinsengumi: The Shogun's Last Samurai Corps. (Tuttle Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0804836272), 4

- ↑ Tōgō Shrine and Tōgō Association (東郷神社・東郷会), Togo Heihachiro in images, illustrated Meiji Navy. (図説東郷平八郎、目で見る明治の海軍), (Japanese) Togo Heihachiro, II.

- ↑ Togo Heiachiro, I7.

- ↑ Togo Heihachiro, II.

- ↑ Togo Heihachiro, II.

- ↑ Rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 19, 2008

- ↑ Christopher Howe. The origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, Development and technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War. (The University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0226354857), 281

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 17

- ↑ Kathrin Milanovich, "Chiyoda (II): First Armoured Cruiser of the Imperial Japanese Navy." Warship 2006, edited by John Jordan. (London: Anova. Conway Maritime Press, 2006, ISBN 1844860302)

- ↑ Rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy. Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 19, 2008

- ↑ Video footage of the Sino-Japanese war: Video footage of a naval battle (external link) Retrieved June 20, 2008.

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 60–61.

- ↑ Sir Julian Stafford Corbett, John B. Hattendorf, and Donald M. Schurman. Maritime operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1994. ISBN 1557501297), 333

- ↑ Howe, 284

- ↑ Howe, 268

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 150-151.

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 84.

- ↑ Bernard Ireland. Jane's battleships of the 20th century. (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0004709977), 68

- ↑ Wakamiya is "credited with conducting the first successful carrier air raid in history" Source: GlobalSecurity.org Retrieved June 19, 2008

- ↑ Polak, 92.

- ↑ IJN Wakamiya Aircraft Carrier GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 161

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997, 212.

- ↑ David Lyon and Hugh Lyon. World War II warships, Edited By Antony Preston. (New York: Excalibur Books, 1976. ISBN 0525700579), 34

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997.

- ↑ Edward S. Miller. War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991.)

- ↑ Alfred T. Mahan. The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783. (original 1918) reprint ed. (Boston: Little, Brown.)

- ↑ Miller, 1991

- ↑ Evans and Peattie, 1997; and H. P. Willmott. The Barrier and the Javelin. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983).

- ↑ "The Imperial Japanese Navy was a pioneer in naval aviation, having commissioned the world's first built-from-the-keel-up carrier, the Hosho." Rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved April 18, 2009.

- ↑ The British had used 18-inch guns during the First World War, as experiments and then to arm monitors.

- ↑ Bernard Fitzsimons, (ed.) The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. (London: Phoebus, 1978, Volume 3, 10), 1041, "Fubuki".

- ↑ J. N. Westwood. Fighting ships of World War II. (Chicago: Follett Pub. Co., 1975. ISBN 0695806130).

- ↑ Rise of the Imperial Japanese Navy. globalsecurity.org. Retrieved June 18, 2008

- ↑ Lyon, World War II warships 35.

- ↑ Howe, 286.

- ↑ Mark Parillo. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II. (Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1993. ISBN 1557506779).

- ↑ "In many ways the Japanese were in the forefront of carrier design, and in 1941, the two Shōkakus — the culmination of prewar Japanese design — were superior to any carrier in the world then in commission." Evans and Peattie, 1997, 323.

- ↑ "For speed and maneuverability, for example the Zero was matchless; for range and speed few bombers surpassed the Mitsubishi G3M, and in the Kawanishi H8K, the Japanese navy had the world's best flying boat" Evans and Peattie, 1997, 312.

- ↑ "by 1941, by training and experience, Japan's naval aviators were undoubtedly the best among the world's three carrier forces" Evans and Peattie, 1997, 325.

- ↑ United States. Japanese submarines. ONI 220-J. (Washington: Publications and Distribution Branch, Division of Naval Intelligence, 1944), 70.

- ↑ Valor at Sea,Tonnage Sunk, Pacific 1941 - 1945 Valoratsea.com. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boxer, C. R. The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650. (original 1951) reprint ed. Manchester: Carcanet Press Ltd, 1993. ISBN 1857540352.

- D'Albas, Andrieu. Death of a Navy: Japanese Naval Action in World War II. Devin-Adair Pub. 1965. ISBN 081595302X

- Corbett, Julian Stafford, Sir, John B. Hattendorf, and D. M. (Donald M.) Schurman. Maritime operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. 1994. ISBN 1557501297.

- Delorme, Pierre. Les Grandes Batailles de l'Histoire, Port-Arthur 1904. Socomer Editions (French)

- Dull, Paul S. A Battle History of The Imperial Japanese Navy. 1978. ISBN 085059295X.

- Evans, David C., & Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: strategy, tactics, and technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 0870211927.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. London: Phoebus; and New York: Columbia Books, 1978.

- Gardiner, Robert, and Andrew Lambert, eds. Steam, Steel and Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. (Conway's History of the Ship) Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992; reprint ed. 2001. ISBN 0785814132.

- Hara, Tameichi. Japanese Destroyer Captain. New York & Toronto: Ballantine Books, 1961. ISBN 0345278941.

- Hillsborough, Romulus. Shinsengumi: The Shogun's Last Samurai Corps. Tuttle Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0804836272.

- Howarth, Stephen. The fighting ships of the Rising Sun: the drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895-1945. New York: Atheneum, 1983. ISBN 0689114028.

- Howe, Christopher. The origins of Japanese Trade Supremacy, Development and technology in Asia from 1540 to the Pacific War. University of Chicago Press, 1996. ISBN 0226354857.

- Ireland, Bernard. Jane's Battleships of the 20th Century. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0004709977.

- Lacroix, Eric and Linton Wells. Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War. Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 0870213113.

- Lyon, David and Hugh Lyon. World War II warships, Edited By Antony Preston. New York: Excalibur Books, 1976. ISBN 0856132209.

- Miller, Edward S. War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991.

- Nagazumi, Yōko (永積洋子) Red Seal Ships (朱印船). Tokyo: ISBN 4642066594. (Japanese)

- Parillo, Mark. Japanese Merchant Marine in World War II. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute Press, 1993. ISBN 1557506779.

- Polak, Christian. Soie et lumières: l'âge d'or des échanges franco-japonais. (Kinu to hikari: shirarezaru Nichi-Futsu kōryū 100-nen no rekishi (Edo jidai-1950-nendai). (bilingual French and Japanese) Tōkyō: Ashetto Fujin Gahōsha, 2002. ISBN 4573062106. and Paris: Hachette Fujingaho. ISBN 4573062106.

- Seki, Eiji. Mrs. Ferguson's Tea-Set, Japan and the Second World War: The Global Consequences Following Germany's Sinking of the SS Automedon in 1940. London: Global Oriental. 2006. ISBN 1905246285. [reprinted by University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 2007, previously announced as Sinking of the SS Automedon and the Role of the Japanese Navy: A New Interpretation.]

- Tōgō Shrine and Tōgō Association (東郷神社・東郷会), Togo Heihachiro in images, illustrated Meiji Navy. (図説東郷平八郎、目で見る明治の海軍), (Japanese)

- Japanese submarines 潜水艦大作戦, Jinbutsu publishing (新人物従来社) (Japanese)

- "The Imperial Japanese Navy" (The History Channel, 2004), a 120–minutes documentary.

- Westwood, J. N. Fighting ships of World War II. Chicago: Follett Pub. Co., 1975. ISBN 0695806130.

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.