Aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship designed to deploy and, in most cases recover, aircraft, acting as a sea-going airbase. Aircraft carriers thus allow a naval force to project air power great distances without having to depend on local bases for staging aircraft operations. Modern navies that operate such ships treat the aircraft carrier as the capital ship of the fleet, a role previously played by the battleship. This change, which took place during World War II, was driven by the superior range, flexibility, and effectiveness of carrier-launched aircraft.

The supercarrier, typically displacing 75,000Â tonnes or more, has been the pinnacle of carrier development since their introduction. Most are powered by nuclear reactors and form the core of a fleet designed to operate far from home. Amphibious assault carriers (such as USS Tarawa or HMS Ocean), operate a large contingent of helicopters for the purpose of carrying and landing Marines. They are also known as "commando carriers" or "helicopter carriers."

Lacking the firepower of other warships, aircraft carriers by themselves are considered vulnerable to attack by other ships, aircraft, submarines, or missiles, and therefore travel as part of a carrier battle group (CVBG) for their protection. Unlike other types of capital ships in the twentieth century, aircraft carrier designs since World War II have been effectively unlimited by any consideration save budgetary, and the ships have increased in size to handle the larger aircraft: The large, modern Nimitz class of United States Navy carriers has a displacement nearly four times that of the World War II-era USS Enterprise, yet its complement of aircraft is roughly the sameâa consequence of the steadily increasing size of military aircraft over the years.

Flight deck design

As "runways at sea," modern aircraft carriers have a flat-top deck design that serves as a flight deck for take-off and landing of aircraft. Aircraft take off to the front, into the wind, and land from the rear. Carriers steam at speed, for example up to 35Â knots (65Â km/h), into the wind during take-off in order to increase the apparent wind speed, thereby reducing the speed of the aircraft relative to the ship. On some ships, a steam-powered catapult is used to propel the aircraft forward assisting the power of its engines and allowing it to take off in a shorter distance than would otherwise be required, even with the headwind effect of the ship's course. On other carriers, aircraft do not require assistance for take offâthe requirement for assistance relates to aircraft design and performance. Conversely, when landing on a carrier, conventional aircraft rely upon a tailhook that catches on arrestor wires stretched across the deck to bring them to a stop in a shorter distance than normal. Other aircraftâhelicopters and V/STOL (Vertical/Short Take-Off and Landing) designsâutilize their hover capability to land vertically and so require no assistance in speed reduction upon landing.

Conventional ("tailhook") aircraft rely upon a landing signal officer (LSO) to control the plane's landing approach, visually gaging altitude, attitude, and speed, and transmitting that data to the pilot. Before the angled deck emerged in the 1950s, LSOs used colored paddles to signal corrections to the pilot. From the late 1950s onward, visual landing aids such as mirrors provided information on proper glide slope, but LSOs still transmit voice calls to landing pilots by radio.

Since the early 1950s, it has been common to direct the landing recovery area off to port at an angle to the line of the ship. The primary function of the angled deck landing area is to allow aircraft who miss the arresting wires, referred to as a "bolter," to become airborne again without the risk of hitting aircraft parked on the forward parts of the deck. The angled deck also allows launching of aircraft at the same time as others land.

The above deck areas of the warship (the bridge, flight control tower, and so on) are concentrated to the starboard side of the deck in a relatively small area called an "island." Very few carriers have been designed or built without an island and such a configuration has not been seen in a fleet-sized carrier. The "flush deck" configuration proved to have very significant drawbacks, complicating navigation, air traffic control and numerous other factors.

A more recent configuration, used by the British Royal Navy, has a "ski-jump" ramp at the forward end of the flight deck. This was developed to help launch VTOL (or STOVL) aircraft (aircraft that are able to take off and land with little or no forward movement) such as the Sea Harrier. Although the aircraft are capable of flying vertically off the deck, using the ramp is more fuel efficient. As catapults and arrestor cables are unnecessary, carriers with this arrangement reduce weight, complexity, and space needed for equipment. The disadvantage of the ski jumpâand hence, the reason this configuration has not appeared on American supercarriersâis the penalty that it exacts on aircraft size, payload, and fuel load (and hence, range): Large, slow planes such as the E-2 Hawkeye and heavily-laden strike fighters like the F/A-18E/F Super Hornet cannot use a ski jump because their high weight requires either a longer takeoff roll than is possible on a carrier deck, or catapult assistance.

History and milestones

Though aircraft carriers are given their definition with respect to fixed-wing aircraft, the first known instance of using a ship for airborne operations occurred in 1806, when the British Royal Navy's Lord Thomas Cochrane launched kites from the 32-gun frigate HMS Pallas in order to drop propaganda leaflets on the French territory.

Balloon carriers

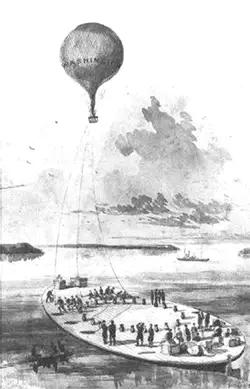

On July 12, 1849, the Austrian Navy ship Vulcano launched a manned hot air balloon in order to drop bombs on Venice, although the attempt failed due to contrary winds.[1]

Later, during the American Civil War, about the time of the Peninsula Campaign, gas-filled balloons were being used to perform reconnaissance on Confederate positions. The battles soon turned inland into the heavily forested areas of the Peninsula, however, where balloons could not travel. A coal barge, the George Washington Parke Custis, was cleared of all deck rigging to accommodate the gas generators and apparatus of balloons. From the GWP Prof. Thaddeus S.C. Lowe, Chief Aeronaut of the Union Army Balloon Corps, made his first ascents over the Potomac River and telegraphed claims of the success of the first aerial venture ever made from a water-borne vessel. Other barges were converted to assist with the other military balloons transported about the eastern waterways. It is only fair to point out in deference to modern aircraft carriers that none of these Civil War crafts had ever taken to the high seas.

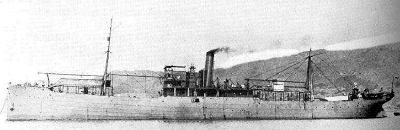

Balloons launched from ships led to the development of balloon carriers, or balloon tenders, during World War I, by the navies of Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Russia, and Sweden. About ten such "balloon tenders" were built, their main objective being aerial observation posts. These ships were either decommissioned or converted to seaplane tenders after the war.

Seaplane carriers

The invention of the seaplane in March 1910 with the French Le Canard led to the earliest development of a ship designed to carry airplanes, albeit equipped with floats: The French Navy La Foudre appeared in December 1911, the first seaplane carrier, and the first known carrier of airplanes. Commissioned as a seaplane tender, and carrying float-equipped planes under hangars on the main deck, from where they were lowered on the sea with a crane, she participated in tactical exercises in the Mediterranean in 1912. La Foudre was further modified in November 1913, with a 10 meter long flat deck to launch her seaplanes.[2]

HMS Hermes, was the first experimental seaplane carrier in the Royal Navy. Built as a Highflyer-class protected cruiser for the Royal Navy in 1898, she was assigned to the reserve Third Fleet in 1913. The ship was modified later that year and in that year's annual fleet maneuvers, she was used to evaluate how aircraft could cooperate with the fleet and if aircraft could be operated successfully at sea for an extended time. The trials were a success. She was recommissioned at the beginning of World War I in August 1914, and sunk by a German submarine in October 1914.[3] The first seaplane tender of the U.S. Navy was the USS Mississippi, converted to that role in December 1913.[4]

Many cruisers and capital ships of the inter-war years often carried a catapult launched seaplane for reconnaissance and spotting the fall of the guns. It was launched by a catapult and recovered by crane from the water after landing. These were highly successful during World War II; there were many notable successes early in the war as shown by HMS Warspiteâs float equipped Swordfish during operations in the Norwegian fjords in 1940. The Japanese Rufe floatplane derived from the Zero was a formidable fighter with only a slight loss in flight performance, one of their pilots scored 26 kills in the A6M2-N Rufe; a score only bettered by a handful of American pilots throughout WWII. Other Japanese seaplanes launched from tenders and warships sank merchant ships and small-scale ground attacks. The culmination of the type was the American 300+ mph (480Â km/h) Curtiss SC Seahawk which was actually a fighter aircraft like the Rufe in addition to a two-seat gunnery spotter and transport for an injured man in a litter. Spotter seaplane aircraft on U.S. Navy cruisers and battleships were in service until 1949. Seaplane fighters were considered poor combat aircraft compared to their carrier-launched brethren; they were slower due to the drag of their pontoons or boat hulls. Contemporary propeller-driven, land-based fighter aircraft were much faster (450-480 mph / 720â770Â km/h as opposed to 300-350 mph / 480â560Â km/h) and more heavily armed. The Curtiss Seahawk only had two 0.50 inch (12.7Â mm) caliber machine guns compared to four 20Â mm cannon in the Grumman F8F Bearcat or four 0.50 (12.7Â mm) cal machine guns plus two 20Â mm cannon in the Vought F4U Corsair. Jet aircraft of just a few years later were faster still (500+ mph) and still better armed, especially with the development of air to air missiles in the early to mid 1950s.

Genesis of the flat-deck carrier

As heavier-than-air aircraft developed in the early twentieth century, various navies began to take an interest in their potential use as scouts for their big gun warships. In 1909, the French inventor Clément Ader published in his book L'Aviation Militaire, the description of a ship to operate airplanes at sea, with a flat flight deck, an island superstructure, deck elevators and a hangar bay.[5]

A number of experimental flights were made to test the concept. Eugene Ely was the first pilot to launch from a stationary ship in November 1910. He took off from a structure fixed over the forecastle of the U.S. armored cruiser USS Birmingham at Hampton Roads, Virginia and landed nearby on Willoughby Spit after some five minutes in the air.

On January 18, 1911, he became the first pilot to land on a stationary ship. He took off from the Tanforan racetrack and landed on a similar temporary structure on the aft of USS Pennsylvania anchored at the San Francisco waterfrontâthe improvised braking system of sandbags and ropes led directly to the arrestor hook and wires described above. His aircraft was then turned around and he was able to take off again. Commander Charles Samson, RN, became the first airman to take off from a moving warship on May 2, 1912. He took off in a Short S27 from the battleship HMS Hibernia while she steamed at 10.5Â knots (19Â km/h) during the Royal Fleet Review at Weymouth.

World War I

The first strike from a carrier against a land target as well as a sea target took place in September 1914, when the Imperial Japanese Navy seaplane carrier Wakamiya conducted the world's first naval-launched air raids[6] from Kiaochow Bay during the Battle of Tsingtao in China.[7] The four Maurice Farman seaplanes bombarded German-held land targets (communication centers and command centers) and damaged a German minelayer in the Tsingtao peninsula from September until November 6, 1914, when the Germans surrendered.[6] On the Western front the first naval air raid occurred on December 25, 1914, when twelve seaplanes from HMS Engadine, Riviera, and Empress (cross-channel steamers converted into seaplane carriers) attacked the Zeppelin base at Cuxhaven. The attack was not a success, though a German warship was damaged.

HMS Ark Royal was arguably the first modern aircraft carrier. She was originally laid down as a merchant ship, but was converted on the building stocks to be a hybrid airplane/seaplane carrier with a launch platform. Launched September 5, 1914, she served in the Dardanelles campaign and throughout World War I.

Other carrier operations were mounted during the war, the most successful taking place on July 19, 1918, when seven Sopwith Camels launched from HMS Furious attacked the German Zeppelin base at Tondern, with two 50Â lb bombs each. Several airships and balloons were destroyed, but as the carrier had no method of recovering the aircraft safely, two of the pilots ditched their aircraft in the sea alongside the carrier while the others headed for neutral Denmark.

Inter-war years

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 placed strict limits on the tonnages of battleships and battlecruisers for the major naval powers after World War I, as well as limits not only on the total tonnage for carriers, but also an upper limit on 27,000Â tonnes for each ship. Although exceptions were made regarding the max ship tonnage (fleet units counted, experimental units did not), the total tonnage could not be exceeded. However, while all of the major navies were over-tonnage on battleships, they were all considerably under-tonnage on aircraft carriers. Consequently, many battleships and battlecruisers under construction (or in service) were converted into aircraft carriers. The first ship to have a full length flat deck was HMS Argus, the conversion of which was completed in September 1918, with the U.S. Navy not following suit until 1920, when the conversion of USS Langley (an experimental ship which did not count against America's carrier tonnage) was completed. The first American fleet carriers would not join the service until 1928 (USS Lexington and Saratoga).

The first purpose-designed aircraft carrier to be developed was the HMS Hermes, although the first one to be commissioned was the Japanese HĆshĆ (commissioned in December 1922, followed by HMS Hermes in July 1924).[9] Hermes' design preceded and influenced that of HĆshĆ, and its construction actually began earlier, but numerous tests, experiments, and budget considerations delayed its commission.

By the late 1930s, aircraft carriers around the world typically carried three types of aircraft: Torpedo bombers, also used for conventional bombings and reconnaissance; dive bombers, also used for reconnaissance (in the U.S. Navy, this type of aircraft were known as "scout bombers"); and fighters for fleet defense and bomber escort duties. Because of the restricted space on aircraft carriers, all these aircraft were of small, single-engined types, usually with folding wings to facilitate storage.

World War II

Aircraft carriers played a significant role in World War II. With seven aircraft carriers afloat, the British Royal Navy had a considerable numerical advantage at the start of the war, as neither the Germans nor the Italians had carriers of their own. However, the vulnerability of carriers compared to traditional battleships when forced into a gun-range encounter was quickly illustrated by the sinking of HMS Glorious by German battlecruisers during the Norwegian campaign in 1940.

This apparent weakness to battleships was turned on its head in November 1940, when HMS Illustrious launched a long-range strike on the Italian fleet at Taranto. This operation incapacitated three of the six battleships in the harbor at a cost of two of the 21 attacking Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers. Carriers also played a major part in reinforcing Malta, both by transporting planes and by defending convoys sent to supply the besieged island. The use of carriers prevented the Italian Navy and land-based German aircraft from dominating the Mediterranean theater.

In the Atlantic, aircraft from HMS Ark Royal and HMS Victorious were responsible for slowing Bismarck during May 1941. Later in the war, escort carriers proved their worth guarding convoys crossing the Atlantic and Arctic oceans.

Many of the major battles in the Pacific involved aircraft carriers. Japan started the war with ten aircraft carriers, the largest and most modern carrier fleet in the world at that time. There were six American aircraft carriers at the beginning of the hostilities, although only three of them were operating in the Pacific.

Drawing on the 1939 Japanese development of shallow water modifications for aerial torpedoes and the 1940 British aerial attack on the Italian fleet at Taranto, the 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor was a clear illustration of the power projection capability afforded by a large force of modern carriers. Concentrating six flattops in a single striking unit marked a turning point in naval history, as no other nation had fielded anything comparable. (Though Germany and Italy began construction of carriers, neither were completed. Of the two, Germany's Graf Zeppelin had the greater potential.)

Meanwhile, the Japanese began their advance through Southeast Asia and the sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse by Japanese land-based aircraft drove home the need for this ship class for fleet defense from aerial attack. In April 1942, the Japanese fast carrier strike force ranged into the Indian Ocean and sank shipping, including the damaged and undefended carrier HMS Hermes. Smaller Allied fleets with inadequate aerial protection were forced to retreat or be destroyed. In the Coral Sea, U.S. and Japanese fleets traded aircraft strikes in the first battle where neither side's ships sighted the other. At the Battle of Midway, all four Japanese carriers engaged were sunk by planes from three American carriers (one of which was lost) and the battle is considered the turning point of the war in the Pacific. Notably, the battle was orchestrated by the Japanese to draw out American carriers that had proven very elusive and troublesome to the Japanese.

Subsequently, the U.S. was able to build up large numbers of aircraft aboard a mixture of fleet, light and (newly commissioned) escort carriers, primarily with the introduction of the Essex class in 1943. These ships, around which were built the fast carrier task forces of the Third and Fifth Fleets, played a major part in winning the Pacific war. The eclipse of the battleship as the primary component of a fleet was clearly illustrated by the sinking of the largest battleship ever built, Yamato, by carrier-borne aircraft in 1945. Japan also built the largest aircraft carrier of the war, Shinano, which was a Yamato class ship converted mid-way through construction after the disastrous loss of four fleet carriers at Midway. She was sunk by a patrolling U.S. submarine while in transit shortly after commissioning, but before being fully outfitted or operational in November 1944.

Important innovations just before and during World War II

Hurricane bow

A hurricane bow is a completely enclosed hangar deck, first seen on the American Lexington class aircraft carriers which entered service in 1927. Combat experience proved it to be by far the most useful configuration for the bow of the ship among others that were tried; including second flying-off decks and an anti-aircraft battery (the latter was the most common American configuration during World War II). This feature would be re-incorporated into American carriers post-war. The Japanese carrier TaihĆ was the first of their ships to incorporate it.

Light aircraft carriers

The loss of three major carriers in quick succession in the Pacific led the U.S. Navy to develop the light carrier (CVL) from light cruiser hulls that had already been laid down. They were intended to provide additional fast carriers, as escort carriers did not have the requisite speed to keep up with the fleet carriers and their escorts. The actual U.S. Navy classification was "small aircraft carrier" (CVL), not light. Prior to World War II, they were just classified as aircraft carriers (CV).[10]

The British Royal Navy made a similar design which served both them and Commonwealth countries after World War II. One of these carriers, India's INS Viraat, formerly HMS Hermes, is still being used.

Escort carriers and merchant aircraft carriers

To protect Atlantic convoys, the British developed what they called Merchant Aircraft Carriers, which were merchant ships equipped with a flat deck for half a dozen aircraft. These operated with civilian crews, under merchant colors, and carried their normal cargo besides providing air support for the convoy. As there was no lift or hangar, aircraft maintenance was limited and the aircraft spent the entire trip sitting on the deck.

These served a as stop-gap until dedicated escort carriers could be built in the U.S. (U.S. classification CVE). About a third of the size of a fleet carrier, it carried about two dozen aircraft for anti-submarine duties. Over one hundred were built or converted from merchantmen.

Escort carriers were built in the U.S. from two basic hull designs: One from a merchant ship, and the other from a slightly larger, slightly faster tanker. Besides defending convoys, these were used to transport aircraft across the ocean. Nevertheless, some participated in the battles to liberate the Philippines, notably the Battle off Samar in which six escort carriers and their escorting destroyers briefly took on five Japanese battleships and bluffed them into retreating.

Catapult aircraft merchantmen

As an emergency stop-gap before sufficient merchant aircraft carriers became available, the British provided air cover for convoys using Catapult aircraft merchantman (CAM ships) and merchant aircraft carriers. CAM ships were merchant vessels equipped with an aircraft, usually a battle-weary Hawker Hurricane, launched by a catapult. Once launched, the aircraft could not land back on the deck and had to ditch in the sea if it was not within range of land. Over two years, fewer than 10 launches were ever made, yet these flights did have some success: 6 bombers for the loss of a single pilot.

Post-war developments

Three major post-war developments came from the need to improve operations of jet-powered aircraft, which had higher weights and landing speeds than their propeller-powered forbears. The first jets were tested as early as December 3, 1945; a de Havilland Vampire and jets were operating by the early 1950s from carriers.

Angled decks

During the Second World War, aircraft would land on the flight deck parallel to the long axis of the ship's hull. Aircraft which had already landed would be parked on the deck at the bow end of the flight deck. A crash barrier was raised behind them to stop any landing aircraft which overshot the landing area because its landing hook missed the arrestor cables. If this happened, it would often cause serious damage or injury and even, if the crash barrier was not strong enough, destruction of parked aircraft.

An important development of the early 1950s was the British invention of the angled deck, where the runway was canted at an angle of a few degrees across the ship. If an aircraft misses the arrestor cables, the pilot only needs to increase engine power to maximum to get airborne again and will not hit the parked aircraft because the angled deck points out over the sea. The USS John C. Stennis is an example of an aircraft carrier that utilizes the concept of an angled landing deck.

Steam catapults

The modern steam-powered catapult, powered by steam from the ship's boilers or reactors, was invented by Commander C.C. Mitchell RNVR. It was widely adopted following trials on HMS Perseus between 1950 and 1952, which showed it to be more powerful and reliable than the compressed air catapults which had been introduced in the 1940s.

Landing system

Another British invention was the glide-slope indicator (also known as a "meatball"). This was a gyroscopically-controlled lamp (which used a Fresnel lens) on the port side of the deck which could be seen by the aviator who was about to land, indicating to him whether he was too high or too low in relation to the desired glidepath. It also took into account the effect of the waves on the flight deck. The device became a necessity as the landing speed of aircraft increased.

Nuclear age

The U.S. Navy attempted to become a strategic nuclear force in parallel with the U.S.A.F long range bombers with the project to build United States, which was termed CVA, with the "A" signifying "atomic." This ship would have carried long range twin-engine bombers, each of which could carry an atomic bomb. The project was canceled under pressure from the newly-created United States Air Force, and the letter "A" was re-cycled to mean "attack." But this only delayed the growth of carriers. (Nuclear weapons would be part of the carrier weapons load despite Air Force objections beginning in 1955 aboard USS Forrestal, and by the end of the fifties the Navy had a series of nuclear-armed attack aircraft.)

The U.S. Navy also built the first aircraft carrier to be powered by nuclear reactors. USS Enterprise is powered by eight nuclear reactors and was the second surface warship (after USS Long Beach) to be powered in this way. Subsequent supercarriers, starting with USS Nimitz took advantage of this technology to increase their endurance utilizing only two reactors. The only other nation to have followed the U.S. lead is France, with Charles de Gaulle, although nuclear power is used for submarine propulsion by France, Great Britain, and the former Soviet Union.

Helicopters

The post-war years also saw the development of the helicopter, with a variety of useful roles and mission capability aboard aircraft carriers. Whereas fixed-wing aircraft are suited to air-to-air combat and air-to-surface attack, helicopters are used to transport equipment and personnel and can be used in an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) role, with dipping sonar and air-launched torpedoes and depth charges; as well as anti-surface vessel warfare, with air-launched anti-ship missiles.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the UK and the U.S. converted some of their older carriers into Commando Carriers; sea-going helicopter airfields like HMS Bulwark. To mitigate against the expensive connotations of the term "aircraft carrier," the new Invincible class carriers were originally designated as "through deck cruisers" and were initially helicopter-only craft to operate as escort carriers. The arrival of the Sea Harrier VTOL/STOVL fast jet meant they could carry fixed-wing aircraft, despite their short flight deck.

The U.S. used conventional carriers initially as pure ASW carriers, embarking helicopters and fixed-wing ASW aircraft like the S-2 Tracker. Later, specialized LPH helicopter carriers for the transport of United States Marine Corps troops and their helicopter transports were developed. These were evolved into the LHA and later into the LHD classes of amphibious assault ships, similar to the UK model even to the point of embarking Harrier aircraft, though much larger.

Ski-jump ramp

Still another British invention was the ski-jump ramp as an alternative to contemporary catapult systems. As the Royal Navy retired or sold the last of its World War II-era carriers, they were replaced with smaller ships designed to operate helicopters and the VTOL Sea Harrier fast jet; ships such as HMS Invincible. The ski-jump allowed Harriers to take off with heavier loads, a STOVL option allowing them to take off with a heavier payload despite its usage of space for aircraft parking. It has since been adopted by the navies of several nations.

Post-World War II conflicts

UN carrier operations in the Korean War

The United Nations command began carrier operations against the North Korean Army on July 3, 1950 in response to the invasion of South Korea. Task Force 77 consisted at that time of the carriers USS Valley Forge and HMS Triumph. Before the armistice of July 27, 1953, 12 U.S. carriers served 27 tours in the Sea of Japan as part of the Task Force 77. During periods of intensive air operations as many as four carriers were on the line at the same time, but the norm was two on the line with a third "ready" carrier at Yokosuka able to respond to the Sea of Japan at short notice.

A second carrier unit, Task Force 95, served as a blockade force in the Yellow Sea off the west coast of North Korea. The task force consisted of a Commonwealth light carrier (HMS Triumph, Theseus, Glory, Ocean, and HMAS Sydney) and usually a U.S. escort carrier (USS Badoeng Strait, Bairoko, Point Cruz, Rendova, and Sicily).

Over 301,000 carrier strikes were flown during the Korean War: 255,545 by the aircraft of Task Force 77; 25,400 by the Commonwealth aircraft of Task Force 95, and 20,375 by the escort carriers of Task Force 95. United States Navy and Marine Corps carrier-based combat losses were 541 aircraft. The Fleet Air Arm lost 86 aircraft in combat and the Fleet Air Arm of Australia 15.

U.S. carrier operations in Southeast Asia

The United States Navy fought "the most protracted, bitter, and costly war" (René Francillon) in the history of naval aviation from August 2, 1964 to August 15, 1973, in the waters of the South China Sea. Operating from two deployment points (Yankee Station and Dixie Station), carrier aircraft supported combat operations in South Vietnam and conducted bombing operations in conjunction with the U.S. Air Force in North Vietnam under Operations Flaming Dart, Rolling Thunder, and Linebacker. The number of carriers on the line varied during differing points of the conflict, but as many as six operated at one time during Operation Linebacker.

Twenty-one aircraft carriers (all operational attack carriers during the era except John F. Kennedy) deployed to Task Force 77 of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, conducting 86 war cruises and operating 9,178 total days on the line in the Gulf of Tonkin. 530 aircraft were lost in combat and 329 more in operational accidents, causing the deaths of 377 naval aviators, with 64 others reported missing and 179 taken prisoner-of-war. 205 officers and men of the ship's complements of three carriers (Forrestal, Enterprise, and Oriskany) were killed in major shipboard fires.

Falklands War

During the Falklands War the United Kingdom was able to win a conflict 8,000Â miles (13,000Â km) from home in large part due to the use of the light fleet carrier HMS Hermes and the smaller "through deck cruiser" HMS Invincible. The Falklands showed the value of a VSTOL aircraftâthe Hawker Siddeley Harrier (the RN Sea Harrier and press-ganged RAF Harriers) in defending the fleet and assault force from shore based aircraft and for attacking the enemy. Sea Harriers shot down 21 fast attack jets and suffered no aerial combat losses, although six were lost to accidents and ground fire. Helicopters from the carriers were used to deploy troops and pick up the wounded.

Operations in the Persian Gulf

The U.S. has also made use of carriers in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and to protect its interests in the Pacific. During the 2003 invasion of Iraq, U.S. aircraft carriers served as the primary base of U.S. air power. Even without the ability to place significant numbers of aircraft in Middle Eastern airbases, the United States was capable of carrying out significant air attacks from carrier-based squadrons. Thereafter, U.S. aircraft carriers, such as the USS Ronald Reagan provided air support for counter-insurgency operations in Iraq.

Aircraft carriers today

Aircraft carriers are generally the largest ships operated by navies; a Nimitz class carrier powered by two nuclear reactors and four steam turbines is 1092Â feet (333Â m) long and costs about $4.5 billion. The United States has the majority of aircraft carriers with eleven in service, one under construction, and one on order. Its aircraft carriers are a cornerstone of American power projection capability.

Nine countries maintain a total of 21 aircraft carriers in active service: United States, United Kingdom, France, Russia, Italy, India, Spain, Brazil, and Thailand. In addition the People's Republic of China's People's Liberation Army Navy possesses the former Soviet aircraft carrier Varyag, but most naval analysts believe that they have no intention to operate it, but instead are using Varyag to learn about carrier operations for future Chinese aircraft carriers. South Korea, United Kingdom, Canada, the People's Republic of China, India, Japan, Australia, Chile, Singapore and France also operate vessels capable of carrying and operating multiple helicopters.

Aircraft carriers are generally accompanied by a number of other ships, to provide protection for the relatively unwieldy carrier, to carry supplies, and to provide additional offensive capabilities. This is often termed a battle group or carrier group, sometimes a carrier battle group.

In the early twenty first century, worldwide aircraft carriers are capable of carrying about 1250 aircraft. U.S. carriers account for over 1000 of these. The United Kingdom and France are both undergoing a major expansion in carrier capability (with a common ship class), but the United States will still maintain a very large lead.

Future aircraft carriers

Several nations which currently possess aircraft carriers are in the process of planning new classes to replace current ones. The world's navies still generally see the aircraft carrier as the main future capital ship, with developments such as the arsenal ship, which have been promoted as an alternative, seen as too limited in terms of flexibility.

Military experts such as John Keegan in the closing of The Price of Admiralty, as well as others, have noted that in any future naval conflict between reasonably evenly matched powers, all surface shipsâincluding aircraft carriersâwould be at extreme and disproportionate risk, mainly due to the advanced capabilities of satellite reconnaissance and anti-ship missiles. Contrary to the thrust of most current naval spending, Keegan therefore postulates that eventually, most navies will move to submarines as their main fighting ships, including in roles where submarines play only a minor or no role at the moment.

The Royal Navy is currently planning two new larger STOVL aircraft carriers (as yet only known as CVF) to replace the three Invincible class carriers. These two ships are expected to be named HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales.[11] They will be able to operate up to 48 aircraft and will have a displacement of around 60,000Â tonnes. The two ships are due to enter service in 2012 and 2015, respectively. Their primary aircraft complement will be made up of F-35B Lightning IIs, and their ship's company will number around 1000.

The two ships will be the largest warships ever built for the Royal Navy. Initially to be configured for STOVL operations, the carriers are to be adaptable to allow any type of future generation of aircraft to operate from them.

In June 2005, it was reported by boxun.com that the People's Republic of China would build a US$362 million Future Chinese aircraft carrier with a displacement of 78,000Â tonnes, to be built at the enclosed Jiangnan Shipyard in Shanghai. The ship would carry around 70 fourth-generation jet aircraft (and possibly fifth-generation jet aircraft when available). That report, however, was denied by Chinese defense official Zhang Guangqin. Earlier talks to purchase an aircraft carrier from Russia and France have not borne fruit, although the Chinese did buy the Soviet aircraft carrier ''Varyag''.[12]

Marine Nationale (France)

The French Navy has set in motion plans for a second CTOL aircraft carrier, to supplement Charles de Gaulle. The design is to be much larger, in the range of 65-74,000 metric tons, and will not be nuclear-powered, as Charles de Gaulle is. There are plans to buy the third carrier of the current Royal Navy design for CATOBAR operations (the Thales/BAE Systems design for the Royal Navy is for a STOVL carrier which is reconfigurable to CATOBAR operations).

India started the construction of a 37,500Â tonne, 252Â meter-long Vikrant class aircraft carrier in April 2005. The new carrier will cost US$762 million and will operate MiG 29K Fulcrum, Naval HAL Tejas, and Sea Harrier aircraft along with the Indian-made helicopter HAL Dhruv. The ship will be powered by four turbine engines and when completed will have a range of 7,500Â nautical miles (14,000Â km), carrying 160 officers, 1400 sailors, and 30 aircraft. The carrier is being constructed by a state-run shipyard in Cochin.

Italian Marina Militare

The construction of the conventional powered Marina Militare STOVL aircraft carrier Cavour began in 2001. It is being built by Fincantieri of Italy. After much delay, Cavour was expected to enter service in 2008 to complement the Marina Militare aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi. A second aircraft carrier in the 25-30,000Â tonne range is much desired by the Italian Navy, to replace the already decommissioned helicopter carrier Vittorio Veneto, but for budgetary reasons all further development is on hold. It is provisionally called Alcide de Gasperi.

Russian Navy Commander-in-Chief Adm Vladimir Masorin officially stated on June 23, 2007, that Navy is currently considering a specifications of a new nuclear aircraft carrier design,[13] for the class that was first announced about a month earlier. Production of the carriers is believed to start around 2010, at Zvezdochka plant in Severodvinsk, where the large drydock, capable of launching vessels with more than 100,000 ton displacement, is now being built.

In his statement, Adm. Masorin stated that general dimensions of the project are already determined. The projected carrier is to have a nuclear propulsion, to displace about 50,000 tons and to carry an air wing of 30-50 air superiority aircraft and helicopters, which makes her roughly comparable to French Charles de Gaulle carrier. "The giants that U.S. Navy builds, those that carry 100-130 aircraft, we won't build anything like that," said admiral.[13] The planned specs reflects the role of aircraft carriers as an air support platforms for guided missile cruisers and submarines, traditional for Russian Navy.

Russian naval establishment had long agreed that since the decommission of Kiev class carriers, the only operational carrier, Admiral Kuznetsov was insufficient, and that three or four carriers were necessary to meet the Navy needs for air support. However, the financial and organizational turmoil of the 1990s made even maintenance of Kuznetsov a difficult undertaking. The recent improvement in Russia's economic situation has allowed a major increase in defence spending, and at least two new carriers were believed to be in planning, one each for Northern and Pacific fleets.

The project for the 231 meter-long and 25,000-30,000 tonnes conventional powered Buque de Proyección Estratégica (Strategic projection vessel),as it was initially known, for the Spanish navy was approved in 2003, and its construction started in August 2005, with the shipbuilding firm Navantia in charge of the project. The Buque de proyección estratégica is a vessel designed to operate both as amphibious assault vessel and as VSTOL aircraft carrier, depending on the mission assigned. The design was made keeping in mind the low-intensity conflicts in which the Spanish Navy is likely to be involved in the future. Similar in role to many aircraft carriers, the ship has a ski jump for STOVL operations, and is equipped with the AV-8B Harrier II attack aircraft. The vessel is named in honour of Juan Carlos I, the former King of Spain.

The current U.S. Fleet of Nimitz class carriers are to be followed into service (and in some cases replaced) by the Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) class. It is expected that the ships will be larger than the Nimitz, and will also be designed to be less detectable by radar. The United States Navy is also looking to make these new carriers more automated in an effort to reduce the amount of funding required to build and maintain its supercarriers.

Notes

- â David Bicego, Design and Control of Multi-Directional Thrust Multi-Rotor Aerial Vehicles with applications to Aerial Physical Interaction Tasks September 13, 2019. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â Andrew Toppan, Foudre seaplane cruiser World Aircraft Carriers List: France, November 26, 2001. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â HMS Hermes (1914) Wrecksite.

- â Andrew Toppan, Mississippi battleship/seaplane tender World Aircraft Carriers List: US Seaplane Tenders: Miscellaneous, January 1, 1998. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â Clement Ader, Military Aviation (Montgomery, Al: Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, 2003, ISBN 158566118X), 35.

- â 6.0 6.1 IJN Wakamiya Seaplane Carrier GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â Christian Polak, Sabre et Pinceau (CCI France Japon, 2005), 92.

- â IJN Imperial Japanese Navy/(Nihon Kaigun) GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- â John Jordan, (ed.), Warship 2008 (Naval Institute Press, 2008, ISBN 1844860620).

- â US Navy Aircraft Carriers Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â J. Pike, Queen Elizabeth class Future Aircraft Carrier CVF (002). GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â Liaoning (Varyag) Aircraft Carrier, China Naval Technology, September 24, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- â 13.0 13.1 Commander-in-Chief of the Navy spoke about the future nuclear aircraft carrier Lenta.ru, June 23, 2007. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ader, Clement. Military Aviation. Montgomery, Al: Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, 2003. ISBN 158566118X

- Friedman, Norman. U.S. Aircraft Carriers: an Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1983. ISBN 0870217399

- Francillon, RenĂ© J. Tonkin Gulf Yacht Club US Carrier Operations off Vietnam. Annapolis, MD: Naval Inst Press, 1988. ISBN â 0870216961

- Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2008. Naval Institute Press, 2008. ISBN 1844860620

- Nordeen, Lon. 1985. Air Warfare in the Missile Age, 2nd edition. New York: Smithsonian. ISBN 158834083X

- Polak, Christian. Sabre et Pinceau. CCI France Japon, 2005.

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Haze Gray & Underway, World Aircraft Carrier Lists comprehensive and detailed listings of all the world's aircraft carriers and seaplane tenders from 1913-2001, with photo gallery.

- How Aircraft Carriers Work How Stuff Works

| Warship types of the 19th & 20th Centuries | |

|---|---|

| Aircraft Carrier | Battleship | Battlecruiser | Cruiser | Destroyer | Frigate | Ironclad | Monitor | Submarine | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.