Airship

An airship or dirigible is a buoyant aircraft that can be steered and propelled through the air. It is classified as an aerostatic craft, to indicate that it stays aloft primarily by means of a large cavity filled with a gas of lesser density than the surrounding atmosphere. By contrast, airplanes and helicopters are aerodynamic craft, which means that they stay aloft by moving an airfoil through the air to produce lift.

Airships were the first form of aircraft to make controlled, powered flight. Their widest use took place from roughly 1900 through the 1930s. However, their use decreased over time, as their capabilities were surpassed by those of airplanes. In addition, they suffered a series of high-profile accidentsâmost notably, the burning of the Hindenburg. Today they are used for a variety of niche applications, particularly advertising.

Terminology

In many countries, airships are also known as dirigibles, from the French dirigeable, meaning "steerable." The first airships were called "dirigible balloons." Over time, the word "balloon" was dropped from the phrase.

The term zeppelin is a genericized trademark that originally referred to airships manufactured by the Zeppelin Company.

In modern common usage, the terms zeppelin, dirigible, and airship are used interchangeably for any type of rigid airship, with the terms blimp or airship alone used to describe non-rigid airships. In modern technical usage, however, airship is the term used for all aircraft of this type, with zeppelin referring only to aircraft of that manufacture, and blimp referring only to non-rigid airships.

The term airship is sometimes informally used to mean any machine capable of atmospheric flight.

In contrast to airships, balloons are buoyant aircraft that generally rely on wind currents for movement, though vertical movement can be controlled in both.

There is often some confusion around the term aerostat with regard to airships. This confusion arises because aerostat has two different meanings. One meaning of aerostat refers to all craft that remain aloft using buoyancy. In this sense, airships are a type of aerostat. The other, more narrow and technical meaning of aerostat refers only to tethered balloons. In this second technical sense, airships are distinct from aerostats. This airship/aerostat confusion is often exacerbated by the fact that both airships and aerostats have roughly similar shapes and comparable tail fin configurations, although only airships have motors.

Types

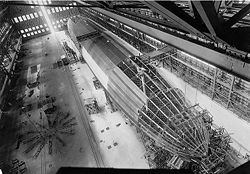

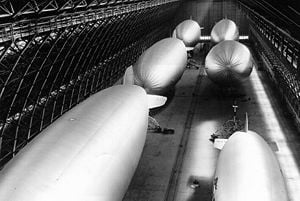

- Rigid airships (for example, Zeppelins) had rigid frames containing multiple, non-pressurized gas cells or balloons to provide lift. Rigid airships did not depend on internal pressure to maintain their shape.

- Non-rigid airships (blimps) use a pressure level in excess of the surrounding air pressure in order to retain their shape.

- Semi-rigid airships, like blimps, require internal pressure to maintain their shape, but have extended, usually articulated keel frames running along the bottom of the envelope to distribute suspension loads into the envelope and allow lower envelope pressures.

- Metal-clad airships had characteristics of both rigid and non-rigid airships, utilizing a very thin, airtight metal envelope, rather than the usual rubber-coated fabric envelope. Only two ships of this type, Schwarz's aluminum ship of 1897 and the ZMC-2, have been built to date.

- Hybrid airship is a general term for an aircraft that combines characteristics of heavier-than-air (airplane or helicopter) and lighter than air technology. Examples include helicopter/airship hybrids intended for heavy lift applications and dynamic lift airships intended for long-range cruising. It should be noted that most airships, when fully loaded with cargo and fuel, are typically heavier than air, and thus must use their propulsion system and shape to generate aerodynamic lift, necessary to stay aloft; technically making them hybrid airships. However, the term "hybrid airship" refers to craft that obtain a significant portion of their lift from aerodynamic lift and often require substantial take-off rolls before becoming airborne.

Lifting gas

In the early days of airships, the primary lifting gas was hydrogen. Until the 1950s, all airships, except for those in the United States, continued to use hydrogen because it offered greater lift and was cheaper than helium. The United States (until then the sole producer) was also unwilling to export helium because it was rare and was considered a strategic material. However, hydrogen is extremely flammable when mixed with air, a quality that some think contributed to the Hindenburg disaster, as well as other rigid airship disasters. In addition, the buoyancy provided by hydrogen is only about 8 percent greater than that of helium. The issue therefore became one of safety versus cost.

American airships have been filled with helium since the 1920s, and modern passenger-carrying airships are often, by law, prohibited from being filled with hydrogen. Nonetheless, some small experimental ships continue to use hydrogen. Other small ships, called thermal airships, are filled with hot air in a fashion similar to hot air balloons.

It is noted that the majority of lighter-than-air gases are either toxic, flammable, corrosive, or a combination of these, with the exception of helium, neon, and water (as steam), limiting use for airships. It is also noted there that both methane and ammonia have on occasion been used to provide lift for weather balloons, and an insulated airship containing steam has been investigated.

History

The development of airships was necessarily preceded by the development of balloons.

Pioneers

Airships were among the first aircraft to fly, with various designs airborne throughout the nineteenth century. They were largely attempts to make relatively small balloons more steerable, and often contained features found on later airships. These early airships set many of the earliest aviation records.

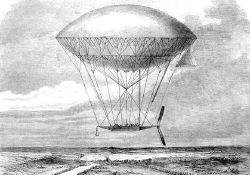

In 1784, Jean-Pierre Blanchard fitted a hand-powered propeller to a balloon, the first recorded means of propulsion carried aloft. In 1785, he crossed the English Channel with a balloon equipped with flapping wings for propulsion, and a bird-like tail for steerage.

The first person to make an engine-powered flight was Henri Giffard who, in 1852, flew 27 km (17 miles) in a steam-powered airship.

In 1863, Dr. Solomon Andrews devised the first fully steerable airship, although it had no motor.

In 1872, the French naval architect Dupuy de Lome launched a large limited navigable balloon, which was driven by a large propeller and the power of eight people. It was developed during the Franco-Prussian war, as an improvement to the balloons used for communications between Paris and the countryside during the Siege of Paris by German forces, but was only completed after the end of the war.

Charles F. Ritchel made a public demonstration flight in 1878 of his hand-powered one-man rigid airship and went on to build and sell five of his aircraft.

Paul Haenlein flew an airship with an internal combustion engine on a tether in Vienna, the first use of such an engine to power an aircraft.

In 1880, Karl Wölfert and Ernst Georg August Baumgarten attempted to fly a powered airship in free flight, but crashed.

In the 1880s a Serb named Ogneslav Kostovic Stepanovic also designed and built an airship. However, the craft was destroyed by fire before it flew.

In 1883, the first electric-powered flight was made by Gaston Tissandier who fitted a 1-1/2 horsepower Siemens electric motor to an airship. The first fully controllable free-flight was made in a French Army airship, La France, by Charles Renard and Arthur Krebs in 1884. The 170 foot long, 66,000 cubic foot airship covered 8 km (5 miles) in 23 minutes with the aid of an 8-1/2 horsepower electric motor.

In 1888, Wölfert flew a Daimler-built petrol engine powered airship at Seelburg.

In 1896, a rigid airship created by Croatian engineer David Schwarz made its first flight at Tempelhof field in Berlin. After Schwarz's death, his wife, Melanie Schwarz, was paid 15,000 Marks by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin for information about the airship.

In 1901, Alberto Santos-Dumont, in his airship "Number 6," a small blimp, won the Deutsch de la Meurthe prize of 100,000 francs for flying from the Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back in under thirty minutes. Many inventors were inspired by Santos-Dumont's small airships and a veritable airship craze began world-wide. Many airship pioneers, such as the American Thomas Scott Baldwin financed their activities through passenger flights and public demonstration flights. Others, such as Walter Wellman and Melvin Vaniman set their sights on loftier goals, attempting two polar flights in 1907 and 1909, and two trans-Atlantic flights in 1910 and 1912.

The beginning of the "Golden Age of Airships" was also marked with the launch of the Luftschiff Zeppelin LZ1 in July of 1900, which would lead to the most successful airships of all time. These Zeppelins were named after the Count von Zeppelin. Von Zeppelin began experimenting with rigid airship designs in the 1890s leading to some patents and the LZ1 (1900) and the LZ2 (1906). At the beginning of World War I, the Zeppelin airships had a cylindrical aluminum alloy frame and a fabric-covered hull containing separate gas cells. Multi-plane tail fins were used for control and stability, and two engine/crew cars hung beneath the hull driving propellers attached to the sides of the frame by means of long drive shafts. Additionally there was a passenger compartment (later a bomb bay) located halfway between the two cars.

First World War

The prospect of using airships as bomb carriers had been recognized in Europe well before the airships themselves were up to the task. H. G. Wells described the obliteration of entire fleets and cities by airship attack in The War in the Air (1908), and scores of less famous British writers declared in print that the airship had altered the face of world affairs forever. On March 5, 1912, Italian forces became the first to use dirigibles for a military purpose during reconnaissance west of Tripoli behind Turkish lines. It was World War I, however, that marked the airship's real debut as a weapon.

Count Zeppelin and others in the German military believed they had found the ideal weapon with which to counteract British Naval superiority and strike at Britain itself. More realistic airship advocates believed the Zeppelin was a valuable long range scout/attack craft for naval operations. Raids began by the end of 1914, reached a first peak in 1915, and then were discontinued after 1917. Zeppelins proved to be terrifying but inaccurate weapons. Navigation, target selection and bomb-aiming proved to be difficult under the best of conditions. The darkness, high altitudes and clouds that were frequently encountered by zeppelin missions reduced accuracy even further. The physical damage done by the zeppelins over the course of the war was trivial, and the deaths that they caused (though visible) amounted to a few hundred at most. The zeppelins also proved to be vulnerable to attack by aircraft and antiaircraft guns, especially those armed with incendiary bullets. Several were shot down in flames by British defenders, and others crashed en route. In retrospect, advocates of the naval scouting role of the airship proved to be correct, and the land bombing campaign proved to be disastrous in terms of morale, men, and material. Many pioneers of the German airship service died bravely, but needlessly in these propaganda missions. They also drew unwanted attention to the construction sheds, which were bombed by the British Royal Naval Air Service.

Meanwhile the Royal Navy had recognized the need for small airships to counteract the submarine threat in coastal waters, and beginning in February 1915, began to deploy the SS (Sea Scout) class of blimp. These had a small envelope of 60-70,000 cu feet and at first utilized standard single engined planes (BE2c, Maurice Farman, Armstrong FK) shorn of wing and tail surfaces as an economy measure. Eventually more advanced blimps with purpose built cars, such as the C (Coastal), C* (Coastal Star), NS (North Sea), SSP (Sea Scout Pusher), SSZ (Sea Scout Zero), SSE (Sea Scout Experimental) and SST (Sea Scout Twin) classes were developed. The NS class, after initial teething problems proved to be the largest and finest airships in British service. They had a gas capacity of 360,000 cu feet, a crew of 10 and an endurance of 24 hours. Six 230 lb bombs were carried, as well as 3-5 machine guns. British blimps were used for scouting, mine clearance, and submarine attack duties. During the war, the British built over 225 non-rigid airships, of which several were sold to Russia, France, the U.S., and Italy. Britain, in turn, purchased one M-type semi-rigid from Italy whose delivery was delayed until 1918. Eight rigid airships had been completed by the armistice, although several more were in an advanced state of completion by the war's end. The large number of trained crews, low attrition rate, and constant experimentation in handling techniques meant that at the war's end Britain was the world leader in non-rigid airship technology.

Airplanes had essentially replaced airships as bombers by the end of the war, and Germany's remaining zeppelins were scuttled by their crews, scrapped, or handed over to the Allied powers as spoils of war. The British rigid airship program, meanwhile, had been largely a reaction to the potential threat of the German one and was largely, though not entirely, based on imitations of the German ships.

Inter-war period

Airships using the Zeppelin construction method are sometimes referred to as zeppelins even if they had no connection to the Zeppelin business. Several airships of this kind were built in the U.S. and Britain in the 1920s and 1930s, mostly imitating original Zeppelin design derived from crashed or captured German World War I airships.

The British R33 and R34, for example, were near identical copies of the German L-33, which crashed virtually intact in Yorkshire on September 24, 1916. Despite being almost three years out of date by the time they were launched in 1919, these sister ships were two of the most successful in British service. On July 2, 1919, R34 began the first double crossing of the Atlantic by an aircraft. It landed at Mineola, Long Island on July 6, 1919, after 108 hours in the air. The return crossing commenced on July 8 because of concerns about mooring the ship in the open, and took 75 hours. Impressed, British leaders began to contemplate a fleet of airships that would link Britain to its far-flung colonies, but unfortunately post-war economic conditions lead to most airships being scrapped and trained personnel dispersed, until the R-100 and R-101 commenced construction in 1929.

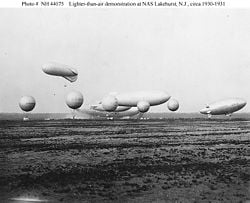

Another example was the first American-built rigid dirigible USS Shenandoah, which flew in 1923, while the Los Angeles was under construction. The ship was christened on August 20, in Lakehurst, New Jersey and was the first to be inflated with the noble gas helium, which was still so rare at the time that the Shenandoah contained most of the world's reserves. So, when the Los Angeles was delivered, it was at first filled with the helium borrowed from ZR-1.

The Zeppelin works were saved by the purchase of what became the USS Los Angeles by the United States Navy, paid for with "war reparations" money, owed according to the Versailles Treaty. The success of the Los Angeles encouraged the United States Navy to invest in larger airships of its own. Germany, meanwhile, was building the Graf Zeppelin, the first of what was intended to be a new class of passenger airships.

Interestingly, the Graf Zeppelin burned unpressurized blau gas, similar to propane, as fuel. Since its density was similar to that of air, it avoided the weight change when fuel was used.

Initially airships met with great success and compiled an impressive safety record. The Graf Zeppelin, for example, flew over one million miles (including the first circumnavigation of the globe by air) without a single passenger injury. The expansion of airship fleets and the growing (sometimes excessive) self-confidence of airship designers gradually made the limits of the type clear, and initial successes gave way to a series of tragic rigid airship accidents.

The "catastrophist theory" of airship development owes much to the sensationalist press of the 1920s and 1930s and ignores successful ships such as Graf Zeppelin, R100, and Los Angeles. The worst disastersâR-101, USS Shenandoah, USS Akron, and Hindenburg were all partially the result of political interference in normal airship construction and flight procedures.

The U.S. Navy toyed with the idea of using airships as "flying aircraft carriers." With wide oceans protecting the homeland, the idea of fleets of airships capable of rapidly crossing them (and the country) to deliver squadrons of fighters to attack approaching enemies had a certain appeal. This was a radical idea, however, and probably did not gain too much support in the Navy's traditional hierarchy. They did, though, build the USS Akron and USS Macon to test the principle. Each airship carried four fighters inside, and could carry a fifth on the "landing hangar." Perhaps the ease with which a fragile airship could be destroyed accidentally was the final justification for not pursuing this idea further.

The USS Los Angeles flew successfully for 8 years, but eventually the U.S. Navy lost all three of its American-built rigid airships to accidents. USS Shenandoah, on a poorly planned publicity flight, flew into a severe thunderstorm over Noble County, Ohio, on September 3, 1925, and broke into pieces, killing 14 of her crew. USS Akron was caught by a microburst and driven down into the surface of the sea off the shore of New Jersey on April 3, 1933. The USS Akron carried no life boats and few life vests. As a result, 73 of her 76-men crew died from drowning or hypothermia. USS Macon broke up after suffering a structural failure in its upper fin off the shore of Point Sur, in California on February 12, 1935. Only 2 of her 83-man crew died in the crash thanks to the inclusion of life jackets and inflatable rafts after the Akron disaster.

Britain suffered its own airship tragedy in 1930 when R-101, an advanced ship for its time, but rushed to completion and sent on a trip to India before she was ready, crashed in France with the loss of 48 out of 54 aboard on October 5. Because of the bad publicity surrounding the crash, the Air Ministry grounded the competing R100 in 1930, and sold it for scrap in 1931. This was despite the fact that the differently-designed R100 had completed a successful transatlantic maiden flight.

The most spectacular and widely remembered airship accident, however, is the burning of the Hindenburg on May 6, 1937, which caused public faith in airships to evaporate in favor of faster, more cost-efficient (albeit less energy-efficient) airplanes. Of the 97 people on board, there were 36 deaths: 13 passengers, 22 aircrew, and one American ground-crewman. (Much controversy persists as to the cause(s) of the accident.)

Most probably the airplane became the transport of choice also because it is less sensitive to wind. Aside from the problems of maneuvering and docking in high winds, the trip times for an upwind versus a downwind trip of an airship can differ greatly, and even crabbing at an angle to a crosswind eats up ground speed. Those differences make scheduling difficult.

Second World War

While Germany determined that airships were obsolete for military purposes in the coming war and concentrated on the development of airplanes, the United States pursued a program of military airship construction even though it had not developed a clear military doctrine for airship use. At the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 7 December 7, 1941, that brought the United States into World War II, it had 10 non-rigid airships:

- 4 K-class: K-2, K-3, K-4, and K-5 designed as a patrol ships built from 1938.

- 3 L-class: L-1, L-2, and L-3 as small training ships, produced from 1938.

- 1 G-class built in 1936 for training.

- 2 TC-class that were older patrol ships designed for land forces, built in 1933. The U.S. Navy acquired them from Army in 1938.

Only K and TC class airships could be used for combat purposes and they were quickly pressed into service against Japanese and German submarines which at that time were sinking U.S. shipping in visual range of U.S. coast. U.S. Navy command, remembering the airship anti-submarine success from WWI, immediately requested new modern anti-submarine airships and on January 2, 1942, formed the ZP-12 patrol unit based in Lakehurst from the 4 K airships. The ZP-32 patrol unit was formed from two TC and two L airships a month later, based at U.S. Navy (Moffet Field) in Sunnyvale in California. An airship training base was created there as well.

In the years 1942â44, approximately 1,400 airship pilots and 3,000 support crew members were trained in the military airship crew training program and the airship military personnel grew from 430 to 12,400. The U.S. airships were produced by the Goodyear factory in Akron, Ohio. From 1942 until 1945, 154 airships were built for the U.S. Navy (133 K-class, ten L-class, seven G-class, four M-class) and five L-class for civilian customers (serial number L-4 to L-8).

The primary airship tasks were patrol and convoy escort near the U.S. coastline. They also served as an organization center for the convoys to direct ship movements, and were used during naval search and rescue operations. Rarer duties of the airships included aerophoto reconnaissance, naval mine-laying and mine-sweeping, parachute unit transport and deployment, cargo and personnel transportation. They were deemed quite successful in their duties with the highest combat readiness factor in the entire U.S. Air Force (87 percent).

During the war, some 532 ships were sunk near the coast by submarines. However, not a single ship of the 89,000 or so in convoys escorted by blimps was sunk by enemy fire. Airships engaged submarines with depth charges and, less frequently, with other on-board weapons. They could match the slow speed of the submarine and bomb it until it was destroyed. Additionally, submerged submarines had no means of detecting an airship approaching.

Only one airship was ever destroyed by a U-boat: on the night of July 18, 1943, a K-class airship (K-74) from ZP-21 division was patrolling the coastline near Florida. Using radar, the airship located a surfaced German submarine. The K-74 made her attack run but the U-boat opened fire first. K-74's depth charges did not release as she crossed the U-boat and the K-74 received serious damage, losing gas pressure and an engine but landing in the water without loss of life. The crew was rescued by patrol boats in the morning, but one crewman, Isadore Stessel, died from a shark attack. The U-Boat, U-134, had been damaged but not significantly. It was attacked by aircraft within the next day or so, sustaining damage that forced it to return to base. It was finally sunk on August 24, 1943, by a British Vickers Wellington near Vigo, Spain.[1]

Some U.S. airships saw action in the European war theater. The ZP-14 unit, operating in the Mediterranean area from June 1944, completely denied the use of the Gibraltar Straits to Axis submarines. Airships from the ZP-12 unit took part in the sinking of the last U-Boat before German capitulation, sinking U-881 on May 6, 1945, together with destroyers Atherton and Mobery.

The Soviet Union used a single airship during the war. The W-12, built in 1939, entered service in 1942, for paratrooper training and equipment transport. It made 1432 runs with 300 metric tons of cargo until 1945. On February 1, 1945, the Soviets constructed a second airship, a Pobieda-class (Victory-class) unit (used for mine-sweeping and wreckage clearing in the Black Sea) which later crashed on January 21, 1947. Another W-class (W-12bis) Patriot was commissioned in 1947 and used mostly for crew training, parades, and propaganda.

Continued use

Although airships are no longer used for passenger transportation, they continued to be used for other purposes, such as advertising and sightseeing.

In recent years, the Zeppelin company has reentered the airship business. Their new model, designated the Zeppelin NT made its maiden flight on September 18, 1997. There are currently three NT aircraft flying. One has been sold to a Japanese company, and was planned to be flown to Japan in the summer of 2004. However, due to delays getting permission from the Russian government, the company decided to transport the airship to Japan by ship.

Blimps continue to be used for advertising and as TV camera platforms at major sporting events. The most iconic of these is the Goodyear blimps. Goodyear operates 3 blimps in the United States. In addition, the Lightship group operates up to 19 advertising blimps around the world.

Airship Management Services, Inc. operates 3 Skyship 600 blimps. Two operate as advertising and security ships in North America and the Caribbean, and one operates under the name SkyCruizer, providing sightseeing tours in Switzerland. Los Angeles-based Worldwide Aeros Corp.[2] produces FAA Type Certified Aeros 40D Sky Dragon airships.

The Switzerland-based Skyship 600 has also played other roles over the years. For example, it was also flown over Athens during the 2004 Summer Olympics as a security measure. In November of 2006, it carried advertising calling it "The Spirit of Dubai" as it began a publicity tour from London to Dubai, UAE on behalf of The Palm Islands, the worlds largest man-made islands created as a residential complex.

Press reports in May 2006 indicated that the U.S. Navy would be starting to fly airships again after a hiatus of nearly 44 years. In November 2006, the U.S. Army purchased an A380+ airship from American Blimp Corporation through a Systems level contract with Northrop Grumman and Booz Allen Hamilton. The airship will start flight tests in late 2007, with a primary goal of carrying 2,500 lb of payload to an altitude of 15,000 kft under remote control and autonomous waypoint navigation. The program will also demonstrate carrying 1,000 lb of payload to 20,000 kft. The platform could be used for Multi-Intelligence collections. Northrop Grumman (formerly Westinghouse) has responsibility for the overall program.

Several companies, such as Cameron Balloons in Bristol, United Kingdom, build hot-air airships. These combine the structures of both hot-air balloons and small airships. The envelope is the normal 'cigar' shape, complete with tail fins, but it is inflated by hot air (as in a balloon), not helium, to provide the lifting force. Below the envelope is a small gondola that carries the pilot (and sometimes 1-3 passengers), along with a small engine and burners that provide the hot air.

Hot-air airships typically cost less to buy and maintain than modern, helium-based blimps, and they can be quickly deflated after flights. This makes them easy to carry in trailers or trucks and inexpensive to store. Such craft are usually very slow moving, with a typical top speed of 15-20 mph. They are mainly used for advertising, but at least one has been used in rainforests for wildlife observation, as they can be easily transported to remote areas.

Present-day research

There are two primary focuses of current research on airships:

- high altitude, long duration, sensor and/or communications platforms

- long distance transport of very large payloads.

The U.S. government is funding two major projects in the high altitude arena. The first is sponsored by U.S. Army Space and Missile Defense Command and is called the Composite Hull High Altitude Powered Platform (CHHAPP). This aircraft is also sometimes referred to as the HiSentinel High-Altitude Airship. This prototype ship made a 5 hour test flight in September 2005. The second project is being sponsored by the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and is called the high-altitude airship (HAA). In 2005, DARPA awarded a contract for nearly $150 million to Lockheed-Martin for prototype development. First flight of the HAA is planned for 2008.

There are also three private companies funding work on high altitude airships. Sanswire is developing high altitude airships they call "Stratellites" and Techsphere is developing a high altitude version of their spherically shaped airships. JP Aerospace has discussed its long-range plans that include not only high altitude communications and sensor applications, but also an "orbital airship" capable of lifting cargo into low earth orbit with a marginal transportation cost of $1 per short ton per mile of altitude.

On January 31, 2006, Lockheed-Martin made the first flight of their secretly built hybrid-airship designated the P-791 at the company's flight test facility on the Palmdale Air Force Plant 42. The P-791 aircraft is very similar in design to the SkyCat design unsuccessfully promoted for many years by the now financially troubled British company Advanced Technology Group. Although Lockheed-Martin is developing a design for the DARPA WALRUS project, the company claimed that the P-791 is unrelated to WALRUS. Nonetheless, the design represents an approach that may well be applicable to WALRUS. Some believe that Lockheed-Martin had used the secret P-791 program as a way to get a "head-start" on the other WALRUS competitor, Aeros.

A privately funded effort to build a heavy-lift aerostatic/aerodynamic hybrid craft, called the Dynalifter, is being carried out by Ohio Airships. The company has stated that they expect to begin test flight of the Dynalifter in Spring of 2006.

21st Century Airships Inc. is a research and development company for airship technologies. Projects have included the development of a spherical shaped airship, as well as airships for high altitude, environmental research, surveillance and military applications, heavy lift and sightseeing. The company's airships have set numerous world records.

Proposed designs and application

There are several proposed long-range/large-payload designs on the "drawing board."

The proposed Aeroscraft is Aeros Corporation's continuation of the now-canceled WALRUS project. This proposed craft is a hybrid airship that, while cruising, obtains two thirds of its lift from helium and the remaining third aerodynamic lift. Jets would be used during take-off and landing.

There is a case for the airship or zeppelin as a medium- to long-distance air cruise ship using helium as a lifting agent. An airship engine need not be a turbojet and could use less expensive fuel or even use biodiesel.

The disadvantage would be an increased journey time and the inability to overfly large mountain ranges. The Rocky Mountains, Alps, and Himalayas, remain as major obstacles to economic airship navigation. However, airship ports would be relatively quiet and might even make use of seaport harbors.

The longer journey times derive from the fact that airships are invariably slower than heavier-than-air passenger aircraft; the Hindenburg's top speed having been 135 km/h (84 mph), the current airship "Spirit of Dubai" (a Skyship 600) can achieve only 50-80 km/h (30-50 mph), and the Zeppelin NT up to 125 km/h (78 mph). This compares to a Boeing 737's cruising speed of just over 900 km/h (560 mph), or normal intercity rail speeds of in excess of 150 km/h (100 mph).

Unless new technology permits greater speeds, anyone using airships over airplanes would need to accept journey durations at least seven times longer, significantly reducing the ability for air travel to "make the world smaller." It is unknown as to whether ecological concerns could drive this motivation sufficiently, or indeed whether the economies could accept such added impracticalities of travel (75 hours for a transatlantic crossing having been normal in the early age of airships).

Airship passengers could have spacious decks inside the hull to give ample room for sitting, sleeping, and recreation. There would be room for restaurants and similar facilities. The potential exists for a market in more leisurely journeys, such as cruises over scenic terrain.

Noteworthy historic prototypes and experiments

The Heli-Stat was an airship/helicopter hybrid built in New Jersey in 1986.

The Aereon was a hybrid aerostatic/aerodynamic craft built in the 1970s.

The Cyclocrane was a hybrid aerostatic/rotorcraft in which the entire airship envelope rotated along its longitudinal axis.

CL160 was a very large semi-rigid airship to be built in Germany by the start-up Cargolifter, but funding ran out in 2002 after a massive hangar was built. The hangar, built just outside Berlin, has since been converted into a resort called "Tropical Islands."

In 2005, there was a short-lived project focused on long distance and heavy lift was the WALRUS HULA sponsored by the U.S. Department of Defense.[3] The primary goal of the research program was to determine the feasibility of building an airship capable of carrying 500 short tons (450 metric tons) of payload a distance of 12,000 miles (20,000 km) and land on an unimproved location without the use of external ballast or ground equipment (such as masts). In 2005, two contractors, Lockheed-Martin and U.S. Aeros Airships were each awarded approximately $3 million to do feasibility studies of designs for WALRUS. In late March 2006, DARPA announced the termination of work on WALRUS after completion of the current Phase I contracts.

Notes

- â U-boat.net, U-134. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- â Aeros Corp, Aircraft Manufacturer of the World. Retrieved August 15, 2007.

- â Defense Industry Daily, US CBO Gives OK to HULA Airships for Airlift (posted 21 Oct 2005). Retrieved August 15, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Archbold, Rich and Ken Marshall. 1994. Hindenberg, an Illustrated History. Lebanon, IN: Warner Books Inc. ISBN 0446517844

- Althoff, William F. 2003. USS Los Angeles: The Navy's Venerable Airship and Aviation Technology. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books. ISBN 1574886207

- Brooks, Peter. 2004. Zeppelin: Rigid Airships 1893-1940. London, UK: Putnam Aeronautical Books. ISBN 0851778453

- Burgess, Charles P. 2004. Airship Design. Honolulu: University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1410211738

- Cross, Wilbur. 2002. Disaster at the Pole. Guilford, CT: The Lyons Press. ISBN 1585744964

- Frederick, Arthur, et al. 1982. Airship Saga: The History of Airships Seen Through the Eyes of the Men Who Designed, Built, and Flew them. New York: Sterling Publishing. ISBN 0713710012

- Griehl, Manfred, and Joachim Dressel. 1990. Zeppelin! The German Airship Story. Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 1854090453

- Khoury, Gabriel Alexander, ed. 2004. Airship Technology. Cambridge Aerospace Series. Cambridge,: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521607531

- McKee, Alexander. 1980. Ice Crash. New York: St Martins Press. ISBN 0312403828

- Mowthorpe, Ces. 1995. Battlebags: British Airships of the First World War. Gloucestershire, UK: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0905778138

- Ventry, Lord, and Eugene Kolesnik. 1976. Jane's Pocket Book 7âAirship Development. Durham, UK: Macdonald Press. ISBN 0356046567

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

General

- Airship Home Page (Provides a list of airship related websites.)

- Airship and Blimp Resources.

- Airship: DJ's Zeppelin Page -(Provides photographs of and ephemera from airships.)

Associations

- The Lighter-than-Air Society. (U.S.-based association for people interested in airships.)

Historical

- Navy Lakehurst Historical Society.

- The Airship Heritage Trust.

- The Golden Age of the Great Passenger Airships: The Collection of Harold G. Dick.

- Simine's U.S. Aviation Patent Database.

Experiments, prototypes, and proposed designs

- White Dwarf Human Powered Blimp.

- SkYacht: The Personal Blimp. (A hot-air airship with a ribbed envelope structure.)

- Dynalifter: "Roadless Trucking."

- JP Aerospace (Building very large V-shaped airships to fly to 140,000 feet.)

- Millennium Airship

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.