First Sino-Japanese War

| First Sino-Japanese War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

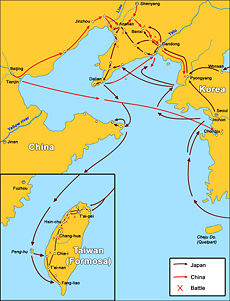

First Sino-Japanese War, major battles and troop movements | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Combatants | |||||||||

| Commanders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 630,000 men Beiyang Army, Beiyang Fleet |

240,000 men | ||||||||

| Casualties | |||||||||

| 35,000 dead or wounded | 13,823 dead, 3,973 wounded | ||||||||

Qing Dynasty China and Meiji Japan fought over the control of Korea in the First Sino-Japanese War (Simplified Chinese: ä¸æ¥ç²åæäº; Traditional Chinese: ä¸æ¥ç²åæ°ç; pinyin: ZhÅngrì JiÇwÇ Zhà nzhÄng; Japanese: æ¥æ¸ æ¦äº Romaji: Nisshin SensÅ) (August 1, 1894â April 17, 1895). The Sino-Japanese War symbolized the degeneration and enfeeblement of the Qing Dynasty and demonstrated how successful modernization had been in Japan since the Meiji Restoration as compared with the Self-Strengthening Movement in China. A shift in regional dominance in Asia from China to Japan, a fatal blow to the Qing Dynasty, and the demise of the Chinese classical tradition represented the principal results of the war. Those trends resulted later in the 1911 Revolution.

With victory, Japan became the major power in East Asia, empowered by Western technology and a well-trained, well-equipped military. Having gained confidence, Japan next challenged and defeated Russia in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904. The United States, under the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, admired Japan's modernization and military might, encouraging Japan to take on the job of civilizing Korea and the rest of East Asia. That naive policy would ultimately lead to Japan's attack upon the United States in World War II. Only with defeat in World War II did Japan cease imperial ambitions.

Korea before the war had a traditional suzerainty relationship with China, the "Middle Kingdom," as its protector and beacon of Confucian culture. Japan's victory over China in 1895 ended China's influence over Korea. It marked the beginning of a 50-year period of colonization by Japan. That colonization inflicted a campaign to replace Korean language and culture with Japanese language and culture as well as economic and political imperialism. As a nation, Korea entered a "dark night of the soul."

Not until after World War II, with the defeat of Japan, could China begin to assume its centuries-old relationship as protector of Korea during the Korean War when China intervened on the behalf of North Korea. China remains today the only country of influence upon the totalitarian communist dictatorship in North Korea and has regained influence with South Korea through trade and investment.

| First Sino-Japanese War |

|---|

| Pungdo (naval) â Seonghwan âPyongyang â Yalu River (naval) â Jiuliangcheng (Yalu) â Lushunkou â Weihaiwei â Yingkou |

Background and causes

Japan has long desired to expand its realm to the mainland of East Asia. During Toyotomi Hideyoshi's rule in the late sixteenth century, Japan invaded Korea (1592-1598) but after initial successes had failed to achieve complete victory and control of Korea.

Following two centuries of the seclusion policy, or Sakoku, under the shoguns of the Edo period, the American intervention forced Japan open to trade with the United States and other European nations in 1854. The fall of the Shogunate at the beginning of the Meiji Restoration of 1868 brought about the transformation of Japan, from a feudal and comparatively backward society to a modern industrial state. The Japanese sent delegations and students around the world with the mission to learn and assimilate western arts and sciences. Japanese leaders believed that modernization along Western lines provided the only way to prevent Japan from falling under foreign domination as well as enabling them to compete equally with the Western powers.

Conflict over Korea

As a newly emergent country, Japan turned its attention towards Korea. Japan's foreign policy called for a two prong approach. One, annexing Korea before China, Russia, or a European power could colonize Korea. Or, two, enhancing Korea's ability to maintain independence through modernization of the nation. Korea has been called "a dagger pointing at Japan's heart." Japan rejected the option of leaving Korea the prey to other powers.

China posed the most immediate threat to Korea and, therefore, Japan's security. Japan's foreign policy aimed to end China's centuries-old suzerainty over Korea. Japan also increased influence in Korea would open Koreaâs coal and iron ore deposits for Japan's industrial use. China, as the Middle Kingdom, controlled Korea through a tribute levy, exerting political influence on Korea most lately during the Qing dynasty. China exerted enormous influence over the conservative Korean officials gathered around the royal family of the Joseon Dynasty.

Korean politicians belonged either to the conservatives who wanted to maintain traditional little brother/big brother relationship with China, or to the progressive reformists who wanted to modernize Korea by establishing closer ties with Japan and western nations. Two Opium Wars and the Sino-French War had rendered China vulnerable to European and American imperialism. Japan saw that as an opportunity to take China's place in Korea. On February 26, 1876, in the wake of confrontations between conservative Korean isolationists and Japanese in Korea, Japan forced Korea to sign the Treaty of Ganghwa, opening to Japanese trade while proclaiming independence from China.

In 1884, a group of pro-Japanese reformers overthrew the pro-Chinese conservative Korean government in a bloody coup d'état. The pro-Chinese faction, with assistance from Chinese troops under General Yuan Shikai, succeeded in regaining control with an equally bloody counter-coup which resulted not only in the deaths of a number of the reformers, but also in the burning of the Japanese legation and the deaths of several legation guards and citizens in the process. That fomented a confrontation between Japan and China, but they proceeded to settle by signing the Sino-Japanese Convention of Tientsin of 1885.

In the Convention of Tientsin, the two sides agreed to (a) pull their expeditionary forces out of Korea simultaneously; (b) not send military instructors for the training of the Korean military; and (c) notify the other side beforehand should one decide to send troops to Korea. In the years that followed, neither Japan nor China lived up to the letter of the agreement. Both coveted control of Korea.

Status of combatants

Japan

Japan's reforms under the Meiji emperor gave priority to naval construction and the creation of an effective modern national army and navy. Japan sent many military officials abroad for training, and evaluation of the strengths and tactics of European armies and navies.

Modeled after the British Royal Navy, at the time the foremost naval power in the world, the Imperial Japanese Navy developed rapidly. British advisors went to Japan to train, advise and educate the naval establishment, while students in turn went to Great Britain to study and observe the Royal Navy. Through drilling and tuition by Royal Navy instructors, Japan developed navy personnel expertly skilled in the arts of gunnery and seamanship.

By the time war broke out, the Imperial Japanese Navy fleet numbered one frigate (Takao), 22 torpedo boats, and numerous [auxiliary/armed merchant cruisers and converted liners. The first battle ship, Izumi, joined the fleet during the war. Japan lacked the resources to build battleships, adopted the "Jeune Ecole" ("young school") doctrine which favored small, fast warships, especially cruisers and torpedo boats, against bigger units to compensate. The British and French built many of Japanâs major warships in their shipyards; eight British, three French, and two Japanese-built. France produced the sections for 16 torpedo boats, Japan assembling them at home.

The Imperial Japanese Army

The Meiji era government at first modeled the army on the French ArmyâFrench advisers had been sent to Japan with the two military missions (in 1872-1880 and 1884; the second and third missions respectively, the first had been under the shogunate). Japan enforced nationwide conscription in 1873, establishing a western-style conscript army. The government built military schools and arsenals to support the army.

In 1886, Japan reformed its army using the German Army, specifically the Prussian as a model. Japan studied Germany's doctrines, military system, and organization in detail.

In 1885, Jakob Meckel, a German adviser implemented new measures such the reorganization of the command structure of the army into divisions and regiments, strengthening army logistics, transportation, and structures thus increasing mobility. Japan instituted artillery and engineering regiments as independent commands. By the 1890s, Japan had built a modern, professionally trained western-style army, well equipped and supplied. The officers had studied abroad, learning the latest tactics and strategy. By the start of the war, the Imperial Japanese Army had a total force of 120,000 men in two armies and five divisions.

| Imperial Japanese Army Composition 1894-1895 |

| 1st Japanese Army |

|---|

| 3rd Provincial Division (Nagoya) |

| 5th Provincial Division (Hiroshima) |

| 2nd Japanese Army |

| 1st Provincial Division (Tokyo) |

| 2nd Provincial Division (Sendai) |

| 6th Provincial Division (Kumamoto) |

| In Reserve |

| 4th Provincial Division (Osaka) |

| Invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) |

| Imperial Guards Division |

China

The Beiyang Force, although well-equipped and symbolizing the new modern Chinese military, suffered from serious morale and corruption problems. Politicians systematically embezzled funds, even during the war. Logistics proved a huge problem, as construction of railroads in Manchuria had been discouraged. The morale of the Chinese armies plummeted from lack of pay, low prestige, use of opium, and poor leadership. Those issues contributed ignominious withdrawals such as the abandonment of the well fortified and defensible Weihaiwei.

Beiyang Army

Qing Dynasty China lacked a national army, but following the Taiping Rebellion, had separated into Manchu, Mongol, Hui (Muslim) and Han Chinese armies, which further divided into largely independent regional commands. During the war, the Beiyang Army and Beiyang Fleet preformed most of the fighting while their pleas for help to other Chinese armies and navies went unheeded due to regional rivalry.

Beiyang Fleet

| Beiyang Fleet |

Major Combatants |

|---|---|

| Ironclad Battleships | Dingyuan (flagship), Zhenyuan |

| Armoured Cruisers | King Yuen, Lai Yuen |

| Protected Cruisers | Chih Yuen, Ching Yuen |

| Cruisers | Torpedo Cruisers - Tsi Yuen, Kuang Ping/Kwang Ping | Chaoyong, Yangwei |

| Coastal warship | Ping Yuen |

| Corvette | Kwan Chia |

13 or so Torpedo boats, numerous gunboats and chartered merchant vessels

Early Stages of the War

In 1893, agents of Yuan Shikai allegedly assassinated Kim Ok-kyun, a pro-Japanese Korean revolutionary, in Shanghai. The Chinese placed his body aboard a Chinese warship and sent it back to Korea. The Korean government, with the support of China, had his body quartered and displayed as a warning to other rebels. The Japanese government took that as a direct affront. The situation became increasingly tense later in the year when the Chinese government, at the request of the Korean Emperor, sent troops to aid in suppressing the Tonghak Rebellion. The Chinese government informed the Japanese government of its decision to send troops to the Korean peninsula in accordance with the Convention of Tientsin, and sent General Yuan Shikai as its plenipotentiary at the head of 2,800 troops.

The Japanese countered that they consider that action a violation of the Convention, and sent their own expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) of 8,000 troops to Korea. The Japanese force subsequently seized the emperor, occupied the Royal Palace in Seoul by June 8, 1894, and replaced the existing government with the members from the pro-Japanese faction.

With China's troops moved to leave Korea, Japan acted quickly. Unpopular with the Conservatives who wanted Japan barred from Korea, the Japanese pressured King Gojong to grant Japan permission to expel the Chinese troops by force. Upon securing his agreement, Japan shipped more troops to Korea. China rejected the legitimacy of the new government, setting the stage for war.

Genesis of the war

- 1 June 1894: The Tonghak Rebellion Army moves towards Seoul. The Korean government requests help from the Chinese government to suppress the rebellion force.

- 6 June 1894: The Chinese government informs the Japanese government under the obligation of Convention of Tientsin of its military operation. China transported 2,465 Chinese soldiers to Korea within days.

- 8 June 1894: First of around 4,000 Japanese soldiers and 500 marines land at Chumlpo (Incheon) despite Korean and Chinese protests.

- 11 June 1894: End of Tonghak Rebellion.

- 13 June 1894: Japanese government telegraphs Commander of the Japanese forces in Korea, Otori Keisuke to remain in Korea for as long as possible despite the end of the rebellion.

- 16 June 1894: Japanese Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu meets with Wang Fengzao, Chinese ambassador to Japan, to discuss the future status of Korea. Wang states that Chinese government intends to pull out of Korea after the rebellion has been suppressed and expects Japan to do the same. However, China also appoints a resident to look after Chinese interests in Korea and to re-assert Koreaâs traditional subservient status to China.

- 22 June 1894: Additional Japanese troops arrive in Korea.

- 3 July 1894: Otori proposes reforms of the Korean political system, which is rejected by the conservative pro-Chinese Korean government.

- 7 July 1894: Mediation between China and Japan arranged by British ambassador to China fails.

- 19 July 1894: Establishment of Japanese Joint Fleet, consisting of almost all vessels in the Imperial Japanese Navy, in preparation for upcoming war.

- 23 July 1894: Japanese troops enter Seoul, seize the Korean Emperor and establish a new pro-Japanese government, which terminates all Sino-Korean treaties and grants the Imperial Japanese Army the right to expel Chinese Beiyang Army troops from Korea.

Events during the war

Opening moves

By July Chinese forces in Korea numbered 3000-3500 and could only be supplied by sea though the Bay of Asan. The Japanese objective was firstly to blockade the Chinese at Asan and then encircle them with their land forces.

Battle of Pungdo On July 25, 1894, the cruisers Yoshino, Naniwa and Akitsushima of the Japanese flying squadron, which had been patrolling off of Asan, encountered the Chinese cruiser Tsi-yuan and gunboat Kwang-yi. Those vessels had steamed out of Asan to meet another Chinese gunboat, the Tsao-kiang, which convoyed a transport toward Asan. After a brief, one hour engagement, the cruiser Tsi-yuan escaped while the Kwang-yi, stranded on rocks, exploded when its powder-magazine ignited.

Sinking of the Kow-shing

The Kow-shing, a 2,134-ton British merchant vessel owned by the Indochina Steam Navigation Company of London, commanded by Captain T. R. Galsworthy and crewed by 64 men, served as a troop transport. Charted by the Qing government to ferry troops to Korea, the Kow-shing and the gunboat Tsao-kiang steamed toward Asan to reinforce Chinese forces with 1200 troops plus supplies and equipment. Major von Hanneken, a German artillery officer acting as an advisor to the Chinese, numbered among the sailors. They had a July 25 arrival schedule.

The cruiser Naniwa (under the command of Captain Togo Heihachiro) intercepted the two ships. The Japanese eventually captured The gunboat, ordering the Kow-shing to follow the Naniwa and requesting that the Europeans on board transfer to the Naniwa. The 1200 Chinese on board desired to return to Taku, threatening to kill the English captain, Galsworthy and his crew. After a four-hour standoff, Captain Togo gave the order to fire upon the vessel. The Europeans jumped overboard, receiving fire from Chinese sailors on board. The Japanese rescued many of the European crew. The sinking of the Kow-shing heightened tensions nearly to the point of war between Japan and Great Britain, but the governments agreed that the action conformed with International Law regarding the treatment of mutineers.

Conflict in Korea

Commissioned by the new pro-Japanese Korean government to expel the Chinese forces from Korean territory by force, Major General Oshima Yoshimasa led mixed Japanese brigades(from the First Japanese Army) numbering about 4,000 on a rapid forced march from Seoul south toward Asan Bay to face 3,500 Chinese troops garrisoned at Seonghwan Station east of Asan and Kongju.

Battle of Seonghwan On July 28, 1894, the two forces met just outside Asan in an engagement that lasted till 0730 hours the next morning, July 29. The Chinese gradually lost ground to the superior Japanese numbers, and finally broke and fled towards Pyongyang. Chinese casualties of 500 killed and wounded compared with 82 for the Japanese.

Formal declaration of War

China and Japan officially declared War on August 1, 1894.

Battle of Pyongyang The remaining Chinese forces in Korea retreated by August 4 to the northern city of Pyongyang, where they eventually joined troops sent from China. The 13,000-15,000 defenders made extensive repairs and preparations to the city, hoping to check the Japanese advance.

The First Army Corp of the Imperial Japanese Army converged on Pyongyang from several directions on September 15, 1894. The Japanese assaulted the city and eventually defeated the Chinese by an attack from the rear, the defenders surrendered. Taking advantage of heavy rainfall and using the cover of darkness, the remaining troops marched out of Pyongyang and headed northeast towards the coast and the city of Uiju. The Chinese suffered casualties of 2000 killed and around 4000 wounded, while the Japanese lost 102 men killed, 433 wounded and 33 missing. The Japanese army entered the city of Pyongyang on the early morning of September 16, 1894.

Offensive into China

Battle of the Yalu River (1894)

The Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed eight out of ten Chinese warships of the Beiyang Fleet off the mouth of the Yalu River on September 17, 1894. Japan secured command of the sea. The Chinese countered by landing 4,500 troops near the Yalu River.

Invasion Of Manchuria

Crossing the Yalu River With the defeat at Pyongyang, the Chinese abandoned Northern Korea, taking up defensive positions and fortifications along their side of the Yalu River. After receiving reinforcements, the Japanese on October 19, pushed at a fast pace north into Manchuria. On the night of October 24, 1894, the Japanese successfully crossed the Yalu near Jiuliangcheng by erecting a pontoon bridge, undetected. By the night of October 25, the Chinese fled in full retreat westwards. The Japanese had established a firm foothold on Chinese territory with the loss of only four killed and 140 wounded.

Campaign in Southern Manchuria The Japanese First Army split into two groups with General Nozu Michitsura's Fifth Provincial Division advancing towards the city of Mukden while Lieutenant General Katsura Taro's Third Provincial Division advanced west along the Liaodong Peninsula pursuing retreating Chinese forces.

Fall of Lushunkou By November 21, 1894, the Japanese had taken the city of Lüshunkou (Port Arthur). The Japanese army massacred thousands of the city's civilian Chinese inhabitants, in an event called the Port Arthur Massacre. By December 10, 1894, Kaipeng (modern Gaixian, Liaoning Province, China) fell to the Japanese 1st Army under Lieutenant General Katsura.

Fall of Weihaiwei and aftermath

The Chinese fleet subsequently retreated behind the Weihaiwei fortifications. Japanese ground forces, which outflanked the harbor's defenses, surprised them. Battle of Weihaiwei land and sea siege lasted 23 days, between January 20 and February 12, 1895.

After Weihaiwei's fall on February 12, 1895, and with the easing of harsh winter conditions, Japanese troops pressed further into southern Manchuria and northern China. By March 1895 the Japanese had fortified posts that commanded the sea approaches to Beijing. That represented the last major battle of the war, although numerous skirmishes broke out.

Battle of Yingkou The Battle of Yingkou fought outside the port town of Yingkou, Manchuria On March 5, 1895.

Japanese Invasion of Formosa (Taiwan) and the Pescadores On March 26, 1895 Japanese forces invaded and occupied the Pescadores Islands off the coast of Taiwan without casualties and March 29, 1895 Japanese forces under Admiral Motonori Kabayama landed in northern Taiwan and proceeded to occupy it.

End of the war

With the Treaty of Shimonoseki, signed on April 17, 1895, China recognized the total independence of Korea, ceded the Liaodong Peninsula (in present-day south of Liaoning Province), Taiwan/Formosa and the Pescadores Islands to Japan "in perpetuity." Additionally, China would pay Japan 200 million Kuping taels as reparation. China also signed a commercial treaty permitting Japanese ships to operate on the Yangtze River, to operate manufacturing factories in treaty ports and to open four more ports to foreign trade. The Triple Intervention later forced Japan to give up the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for another 30 million Kuping taels (450 million yen).

Aftermath

The Japanese success during the war resulted from the modernization and industrialization program inaugurated two decades earlier. The war demonstrated the superiority of Japanese tactics and training through the adoption of a western style military equipment and tactics. The Imperial Japanese Army and Navy inflicted a string of defeats on the Chinese through foresight, endurance, strategy and power of organization. Japanese prestige rose in the eyes of the world. The victory established Japan as a power on equal terms with the west and as the dominant power in Asia.

For China, the war revealed the failure of its government, its policies, the corruption of the administration system and the decaying state of the Qing dynasty (something recognized for decades). Anti-foreign sentiment and agitation grew, culminating in the Boxer Rebellion five years later. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Qing dynasty fell prey to European and American encroachment. That, together with calls for reform and the Boxer Rebellion, led to 1911 revolution and the downfall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.

Although Japan had achieved the goal of ending Chinese influence over Korea, Japan reluctantly had to relinquish the Liaodong Peninsula (Port Arthur) in exchange for an increased financial indemnity from China. The European powers (Russia especially), while having no objection to the other clauses of the treaty, opposed Japan's possession of Port Arthur, since they had designs on it. Russia persuaded Germany and France to join her in applying diplomatic pressure on the Japanese, resulting in the Triple Intervention of April 23, 1895.

In 1898 Russia signed a 25-year lease on Liaodong Peninsula, proceeding establish a naval station at Port Arthur. Although that infuriated the Japanese, they felt more concern with Russian advances towards Korea than in Manchuria. Other powers, such as France, Germany, and Great Britain, took advantage of the situation in China and gained port and trade concessions at the expense of the decaying Qing Empire. Germany acquired Tsingtao and Kiaochow, France acquired Kwang-Chou-Wan, and Great Britain acquired Weihaiwei.

Tensions between Russia and Japan increased in the years after the First Sino-Japanese war. During the Boxer Rebellion, an eight member international force sent forces to suppress and quell the uprising; Russia sent troops into Manchuria as part of that force. After the suppression of the Boxers the Russian Government agreed to vacate the area. Instead, Russia increased the number of its forces in Manchuria by 1903. The Russians repeatedly stalled negotiations between the two nations (1901â1904) to establish mutual recognition of respective spheres of influence (Russia over Manchuria and Japan over Korea). Russia felt strong and confident they could resist pressure to compromise, believing Japan would never war with a European power. Russia had intentions to use Manchuria as a springboard for further expanding its interests in the Far East.

In 1902, Japan formed an alliance with Britain with the understanding that if Japan went to war in the Far East, and a third power entered the fight against Japan, Britain would come to the aid of the Japanese. That proved a check to prevent either Germany or France from intervening militarily in any future war with Russia. British joined the alliance to check the spread of Russian expansion into the Pacific, thereby threatening British interests. Increasing tensions between Japan and Russia resulting from Russia's unwillingness to compromise, and the rising prospect of Korea falling under Russia's domination, led Japan to take action, leading to the Russo-Japanese war of 1904â1905.

War Reparations

After the war, according to the Chinese scholar, Jin Xide, the Qing government paid a total of 340,000,000 taels silver to Japan for war reparations and war trophies, equivalent to (then) 510,000,000 Japanese yen, about 6.4 times the Japanese government revenue. Another Japanese scholar, Ryoko Iechika, calculated that the Qing government paid total $21,000,000 (about one third of revenue of the Qing government) in war reparations to Japan, or about 320,000,000 Japanese yen, equivalent to (then) two and half years of Japanese government revenue.

See also

- History of China

- History of Japan

- History of Korea

- Second Sino-Japanese War

- Sino-Japanese relations

| Diplomacy of the Great Powers 1871-1913 | |

|---|---|

| Great Powers | British Empire | German Empire | French Third Republic | Russian Empire | Austria-Hungary | Italy |

| Treaties and agreements | Treaty of Frankfurt | League of the Three Emperors | Treaty of Berlin | German-Austrian Alliance | Triple Alliance | Reinsurance Treaty | Franco-Russian Alliance | Anglo-Japanese Alliance | Anglo-Russian Entente | Entente Cordiale | Triple Entente |

| Events | Russo-Turkish War | Congress of Berlin | Scramble for Africa | Fleet Acts | The Great Game | First Sino-Japanese War | Fashoda Incident | Pan-Slavism | Boxer Rebellion | Boer War | Russo-Japanese War | First Moroccan Crisis | Dreadnought | Agadir Crisis | Bosnian crisis | Italo-Turkish War | Balkan wars |

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, James. Under the Dragon Flag - My Experiences in the Chino-Japanese War. reprint ed. Bibliobazaar. 2007. ISBN 1426402759

- Chamberlin, William Henry. 1937. Japan over Asia. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. OCLC: 1474788

- KÅdansha. 1993. Japan: an illustrated encyclopedia. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 9784069310980

- Lone, Stewart. 1994. Japan's first modern war: Army and society in the conflict with China, 1894-95. (Studies in military and strategic history.) Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan Press. ISBN 9780312122775

- Paine, S. C. M. 2003. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perception, Power, and Primacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521817141

- Stoddard, Brooke C. "Sino-Japanese War of 1894." Military Heritage 3 (3)(December 2001): 6.

- Thiess, Frank, and Fritz Sallagar. 1937. The voyage of forgotten men (Tsushima). Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Co. OCLC: 1871472

- Warner, Denis, Peggy Warner, and Don Coutts. 1974. The tide at sunrise: a history of the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905. Book Club Associates. OCLC: 60101308

External links

All links retrieved March 28, 2024.

- Under the Dragon Flag - My Experiences in the Chino-Japanese War by James Allen, available for free via Project Gutenberg

- Philo N. McGiffin. The Battle of the Yalu. navyandmarine.org.

- Sarah Paine. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. online Newsletter of the Slavic Society, Hokkaido University.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.