Difference between revisions of "William Tecumseh Sherman" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

===Breakdown and Shiloh=== | ===Breakdown and Shiloh=== | ||

| − | During his time in Louisville, Sherman became increasingly pessimistic about the outlook of the war and repeatedly made estimates of the strength of the rebel forces that proved exaggerated, causing the local press to describe him as "crazy." In the fall of 1861, Sherman experienced what would probably be described today as a [[nervous breakdown]]. He was put on leave and returned to Ohio to recuperate, being replaced in his command by [[Don Carlos Buell]]. | + | During his time in Louisville, Sherman became increasingly pessimistic about the outlook of the war and repeatedly made estimates of the strength of the rebel forces that proved exaggerated, causing the local press to describe him as "crazy." In the fall of 1861, Sherman experienced what would probably be described today as a [[nervous breakdown]]. He was put on leave and returned to Ohio to recuperate, being replaced in his command by [[Don Carlos Buell]]. However, Sherman quickly recovered and returned to service under Maj. Gen. [[Henry W. Halleck]], commander of the Department of the Missouri. Halleck's department had just won a major victory at [[Battle of Fort Henry|Fort Henry]], but he harbored doubts about the commander in the field, Brig. Gen. [[Ulysses S. Grant]], and his plans to capture [[Battle of Fort Donelson|Fort Donelson]]. Unbeknownst to Grant, Halleck offered several officers, including Sherman, command of Grant's army. Sherman refused, saying he preferred serving ''under'' Grant, even though he outranked him. Sherman wrote to Grant from [[Paducah, Kentucky|Paducah]], "Command me in any way. I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the river and railroad, but [I] have faith in you."<ref>Smith, pp, 151-52</ref> |

After Grant was promoted to major general in command of the District of West Tennessee, Sherman served briefly as his replacement in command of the District of Cairo. He got his wish of serving under Grant when he was assigned on March 1, 1862, to the [[Army of West Tennessee]] as commander of the 5th [[division (military)|Division]].<ref>Eicher, p. 485</ref> His first major test under Grant was at the [[Battle of Shiloh]]. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6 took most of the senior Union commanders by surprise. Sherman in particular had dismissed the intelligence reports that he had received from militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General [[Albert Sidney Johnston]] would leave his base at [[Corinth, Mississippi|Corinth]]. He took no precautions beyond strengthening his picket lines, refusing to entrench, build [[abatis]], or push out reconnaissance patrols. At Shiloh, he may have wished to avoid appearing overly alarmed in order to escape the kind of criticism he had received in Kentucky. He had written to his wife that, if he took more precautions, "they'd call me crazy again."<ref>Daniel, p. 138</ref> | After Grant was promoted to major general in command of the District of West Tennessee, Sherman served briefly as his replacement in command of the District of Cairo. He got his wish of serving under Grant when he was assigned on March 1, 1862, to the [[Army of West Tennessee]] as commander of the 5th [[division (military)|Division]].<ref>Eicher, p. 485</ref> His first major test under Grant was at the [[Battle of Shiloh]]. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6 took most of the senior Union commanders by surprise. Sherman in particular had dismissed the intelligence reports that he had received from militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General [[Albert Sidney Johnston]] would leave his base at [[Corinth, Mississippi|Corinth]]. He took no precautions beyond strengthening his picket lines, refusing to entrench, build [[abatis]], or push out reconnaissance patrols. At Shiloh, he may have wished to avoid appearing overly alarmed in order to escape the kind of criticism he had received in Kentucky. He had written to his wife that, if he took more precautions, "they'd call me crazy again."<ref>Daniel, p. 138</ref> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

[[Image:Chattanooga Battle.png|thumb|320px|Map of the Battle of Chattanooga, 1863]] | [[Image:Chattanooga Battle.png|thumb|320px|Map of the Battle of Chattanooga, 1863]] | ||

| − | Sherman developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together. Shortly after Shiloh, Sherman persuaded Grant not to resign from the Army, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General Halleck. | + | Sherman developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together. Shortly after Shiloh, Sherman persuaded Grant not to resign from the Army, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General Halleck. The careers of both officers ascended considerably after that time. Sherman later famously declared that "Grant stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk and now we stand by each other always."<ref>Brockett, p. 175</ref> |

Sherman's military record in 1862–63 was mixed. In December 1862, forces under his command suffered a severe repulse at the [[Battle of Chickasaw Bayou|Battle of Chickasaw Bluffs]], just north of [[Vicksburg, Mississippi|Vicksburg]]. Soon after, his [[XV Corps (ACW)|XV Corps]] was ordered to join Maj. Gen. [[John A. McClernand]] in his successful assault on [[Battle of Arkansas Post|Arkansas Post]], generally regarded as a politically motivated distraction from the effort to capture Vicksburg.<ref>Smith, p. 227</ref> Before the [[Vicksburg Campaign]] in the spring of 1863, Sherman expressed serious reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy,<ref>Smith, pp. 235-36</ref> but he went on to perform well in that campaign under Grant's supervision. | Sherman's military record in 1862–63 was mixed. In December 1862, forces under his command suffered a severe repulse at the [[Battle of Chickasaw Bayou|Battle of Chickasaw Bluffs]], just north of [[Vicksburg, Mississippi|Vicksburg]]. Soon after, his [[XV Corps (ACW)|XV Corps]] was ordered to join Maj. Gen. [[John A. McClernand]] in his successful assault on [[Battle of Arkansas Post|Arkansas Post]], generally regarded as a politically motivated distraction from the effort to capture Vicksburg.<ref>Smith, p. 227</ref> Before the [[Vicksburg Campaign]] in the spring of 1863, Sherman expressed serious reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy,<ref>Smith, pp. 235-36</ref> but he went on to perform well in that campaign under Grant's supervision. | ||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

[[Image:Green meldrim house.jpg|thumb|leftt|200px|Green-Meldrim house where Sherman stayed, upon taking Savannah in 1864.]] | [[Image:Green meldrim house.jpg|thumb|leftt|200px|Green-Meldrim house where Sherman stayed, upon taking Savannah in 1864.]] | ||

After Atlanta, Sherman dismissed the impact of Gen. Hood's attacks against his supply lines and sent George Thomas to defeat him in the [[Franklin-Nashville Campaign]]. Meanwhile, declaring that he could "make Georgia howl,"<ref>Telegram by W.T. Sherman to Gen. U.S. Grant, Oct. 9, 1864, reproduced in ''Sherman's Civil War'', pp. 731-732</ref> Sherman marched with 62,000 men to the port of [[Savannah, Georgia|Savannah]], living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage.<ref>Report by Maj. Gen. W.T. Sherman, Jan. 1, 1865, quoted in Grimsley, p. 200</ref> At the end of this campaign, known as [[Sherman's March to the Sea]], his troops captured Savannah on December 22. Sherman then telegraphed Lincoln, offering him the city as a [[Christmas]] present. | After Atlanta, Sherman dismissed the impact of Gen. Hood's attacks against his supply lines and sent George Thomas to defeat him in the [[Franklin-Nashville Campaign]]. Meanwhile, declaring that he could "make Georgia howl,"<ref>Telegram by W.T. Sherman to Gen. U.S. Grant, Oct. 9, 1864, reproduced in ''Sherman's Civil War'', pp. 731-732</ref> Sherman marched with 62,000 men to the port of [[Savannah, Georgia|Savannah]], living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage.<ref>Report by Maj. Gen. W.T. Sherman, Jan. 1, 1865, quoted in Grimsley, p. 200</ref> At the end of this campaign, known as [[Sherman's March to the Sea]], his troops captured Savannah on December 22. Sherman then telegraphed Lincoln, offering him the city as a [[Christmas]] present. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===The Carolinas=== | ===The Carolinas=== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 69: | ||

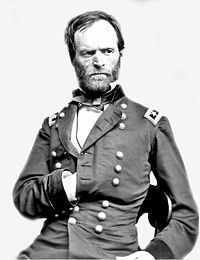

[[Image:Tecumseh sherman.jpg|thumb|200px|Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, USA, in May 1865. The black ribbon around his left arm is a sign of mourning over [[Abraham Lincoln|President Lincoln]]'s death. Portrait by Mathew Brady.]] | [[Image:Tecumseh sherman.jpg|thumb|200px|Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, USA, in May 1865. The black ribbon around his left arm is a sign of mourning over [[Abraham Lincoln|President Lincoln]]'s death. Portrait by Mathew Brady.]] | ||

| − | Sherman captured the state capital of [[Columbia, South Carolina|Columbia]] on February 17 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning, most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were accidental, others a deliberate act of vengeance, and still others that the retreating Confederates burned bales of cotton on their way out of town. | + | Sherman captured the state capital of [[Columbia, South Carolina|Columbia]] on February 17 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning, most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were accidental, others a deliberate act of vengeance, and still others that the retreating Confederates burned bales of cotton on their way out of town. Thereafter, his troops did little damage to the civilian infrastructure. |

Shortly after his victory over Johnston's troops at the [[Battle of Bentonville]], Sherman met with Johnston at [[Bennett Place]] in [[Durham, North Carolina]], to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston and Confederate President [[Jefferson Davis]], Sherman offered generous terms that dealt with both political and military issues, despite having no authorization to do so from either General Grant or the [[United States Cabinet|cabinet]]. The government in [[Washington, D.C.]] refused to honor the terms, precipitating a long-lasting feud between Sherman and [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]] [[Edwin M. Stanton]]. Confusion over this issue lasted until April 26, when Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, agreed to purely military terms and formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.<ref>See, for instance, [http://www.wadehamptoncamp.org/hist-js.html ''Johnston's Surrender at Bennett Place on Hillsboro Road'']</ref> | Shortly after his victory over Johnston's troops at the [[Battle of Bentonville]], Sherman met with Johnston at [[Bennett Place]] in [[Durham, North Carolina]], to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston and Confederate President [[Jefferson Davis]], Sherman offered generous terms that dealt with both political and military issues, despite having no authorization to do so from either General Grant or the [[United States Cabinet|cabinet]]. The government in [[Washington, D.C.]] refused to honor the terms, precipitating a long-lasting feud between Sherman and [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]] [[Edwin M. Stanton]]. Confusion over this issue lasted until April 26, when Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, agreed to purely military terms and formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.<ref>See, for instance, [http://www.wadehamptoncamp.org/hist-js.html ''Johnston's Surrender at Bennett Place on Hillsboro Road'']</ref> | ||

| Line 118: | Line 116: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

*Brockett, L.P., ''Our Great Captains: Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Sheridan, and Farragut'', C.B. Richardson, 1866. | *Brockett, L.P., ''Our Great Captains: Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Sheridan, and Farragut'', C.B. Richardson, 1866. | ||

| − | |||

*Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. | *Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., ''Civil War High Commands'', Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3. | ||

| − | |||

*Grimsley, Mark, ''The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865'', Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-59941-5. | *Grimsley, Mark, ''The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865'', Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-59941-5. | ||

*[[Victor Davis Hanson|Hanson, Victor D]]., ''The Soul of Battle'', Anchor Books, 1999, ISBN 0-385-72059-9. | *[[Victor Davis Hanson|Hanson, Victor D]]., ''The Soul of Battle'', Anchor Books, 1999, ISBN 0-385-72059-9. | ||

*Hirshson, Stanley P., ''The White Tecumseh: A Biography of General William T. Sherman'', John Wiley & Sons, 1997, ISBN 0-471-28329-0. | *Hirshson, Stanley P., ''The White Tecumseh: A Biography of General William T. Sherman'', John Wiley & Sons, 1997, ISBN 0-471-28329-0. | ||

| − | *Hitchcock, Henry, ''Marching with Sherman: Passages from the Letters and Campaign Diaries of | + | *Hitchcock, Henry, ''Marching with Sherman: Passages from the Letters and Campaign Diaries of *Isenberg, Andrew C., ''The Destruction of the Bison'', Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-00348-2. |

| − | *Isenberg, Andrew C., ''The Destruction of the Bison'', Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-00348-2. | ||

*Lewis, Lloyd, ''Sherman: Fighting Prophet'', Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1932. Reprinted in 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7945-0. | *Lewis, Lloyd, ''Sherman: Fighting Prophet'', Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1932. Reprinted in 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7945-0. | ||

*[[Basil Liddell Hart|Liddell Hart, Basil Henry]], ''Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American'', Dodd, Mead & Co., 1929. Reprinted in 1993 by Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80507-3. | *[[Basil Liddell Hart|Liddell Hart, Basil Henry]], ''Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American'', Dodd, Mead & Co., 1929. Reprinted in 1993 by Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80507-3. | ||

*[[John F. Marszalek|Marszalek, John F.]], ''Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order'', Free Press, 1992, ISBN 0-02-920135-7. | *[[John F. Marszalek|Marszalek, John F.]], ''Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order'', Free Press, 1992, ISBN 0-02-920135-7. | ||

* Marszalek, John F., "William Tecumseh Sherman," ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X. | * Marszalek, John F., "William Tecumseh Sherman," ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*Royster, Charles, ''The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans'', Alfred A. Knopf, 1991, ISBN 0-679-73878-9. | *Royster, Charles, ''The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans'', Alfred A. Knopf, 1991, ISBN 0-679-73878-9. | ||

*''Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman,1860-1865'', eds. B.D. Simpson and J.V. Berlin, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8078-2440-2. | *''Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman,1860-1865'', eds. B.D. Simpson and J.V. Berlin, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8078-2440-2. | ||

| Line 137: | Line 130: | ||

*"William Tecumseh Sherman," ''A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography'', Vol. II (1988), p. 741. | *"William Tecumseh Sherman," ''A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography'', Vol. II (1988), p. 741. | ||

*[[Jean Edward Smith|Smith, Jean Edward]], ''Grant'', Simon and Shuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84927-5. | *[[Jean Edward Smith|Smith, Jean Edward]], ''Grant'', Simon and Shuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84927-5. | ||

| − | * | + | **Warner, Ezra J., ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders'', LSU Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7. |

| − | *Warner, Ezra J., ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders'', LSU Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7 | ||

| − | |||

*[[C. Vann Woodward|Woodward, C. Vann]], "Civil Warriors," ''[[New York Review of Books]]'', vol. 37, no. 17, Nov. 8, 1990. | *[[C. Vann Woodward|Woodward, C. Vann]], "Civil Warriors," ''[[New York Review of Books]]'', vol. 37, no. 17, Nov. 8, 1990. | ||

Revision as of 17:11, 25 March 2007

William Tecumseh Sherman (February 8, 1820 – February 14, 1891) was an American soldier, businessman, educator, and author. He served as a general in the United States Army during the American Civil War (1861–65), receiving both recognition for his outstanding command of military strategy, and criticism for the harshness of the "scorched earth" policies he implemented in conducting total war against the enemy. Military historian Basil Liddell Hart famously declared that Sherman was "the first modern general."[1]

After the Civil War, Sherman became Commanding General of the Army (1869–83). As such, he was responsible for the conduct of the Indian Wars in the western United States. He steadfastly refused to be drawn into politics and in 1875 published his Memoirs, one of the best-known firsthand accounts of the Civil War. In 1884, Sherman turned down an opportunity to run for the presidency, living out his life in New York City as a cultured, man about town.

Early life

Sherman was born Tecumseh Sherman in Lancaster, Ohio, near the shores of the Hockhocking River (now the Hocking). He was named Tecumseh after the famous Shawnee leader. His father, Charles Robert Sherman, was a successful lawyer who sat on the Ohio Supreme Court. Judge Sherman died unexpectedly in 1829. He left his widow, Mary Hoyt Sherman, with eleven children and no inheritance. Following this tragedy, the nine-year-old Tecumseh was raised by a Lancaster neighbor and family friend, attorney Thomas Ewing, a prominent member of the Whig Party who served as senator from Ohio and as the first secretary of the interior. Sherman was also distantly related to the very powerful Baldwin, Hoar & Sherman family of US politicians, and was said to be a great admirer of American founding father Roger Sherman. [2]

Military training and service

Senator Ewing secured the appointment of the 16-year-old Sherman as a cadet in the United States Military Academy at West Point.[3] There Sherman excelled academically, but treated the demerit system with indifference. Fellow cadet William Rosecrans would later remember Sherman at West Point as "one of the brightest and most popular fellows," and "a bright-eyed, red-headed fellow, who was always prepared for a lark of any kind."[4]

Upon graduation in 1840, Sherman entered the Army as a second lieutenant in the 3rd U.S. Artillery and saw action in Florida in the Second Seminole War against the Seminole tribe. He was later stationed in Georgia and South`Carolina. As the foster son of a prominent Whig politician, in Charleston, the popular Lt. Sherman moved within the upper circles of Old South society.[5]

While many of his colleagues saw action in the Mexican-American War, Sherman performed administrative duties in the captured territory of California. He and fellow officer Lieutenant Edward Ord reached the town of Yerba Buena two days before its name was changed to San Francisco. In 1848, Sherman accompanied the military governor of California, Col. Richard Barnes Mason, in the inspection that officially confirmed the claim that gold had been discovered in the region, thus inaugurating the California Gold Rush.[6] Sherman earned a brevet promotion to captain for his "meritorious service," but his lack of a combat assignment discouraged him and may have contributed to his decision to resign his commission. Sherman would become one of the relatively few high-ranking officers in the Civil War who had not fought in Mexico.

Marriage and business career

In 1850, Sherman married Thomas Ewing's daughter, Eleanor Boyle ("Ellen") Ewing. Ellen was, like her mother, a devout Catholic and their eight children were raised in that faith. To Sherman's great displeasure and sorrow, one of his sons, Thomas Ewing Sherman, was ordained a Jesuit priest in 1879.[7]

In 1853, Sherman resigned his military commission and became president of a bank in San Francisco. He returned to San Francisco at a time of great turmoil in the West. He survived two shipwrecks and floated through the Golden Gate on the overturned hull of a foundering lumber schooner.[8] Sherman eventually suffered from stress-related asthma because of the city's brutal financial climate.[9] Late in life, regarding his time in real-estate-speculation-mad San Francisco, Sherman recalled: "I can handle a hundred thousand men in battle, and take the City of the Sun, but am afraid to manage a lot in the swamp of San Francisco."[10] In 1856 he served as a major general of the California militia.

Sherman's bank failed during the financial Panic of 1857 and he turned to the practice of law in Leavenworth, Kansas, at which he was also unsuccessful.[11]

University superintendent

In 1859 Sherman accepted a job as the first superintendent of the Louisiana State Seminary of Learning and Military Academy in Pineville, a position offered to him by Major D.C. Buell and General G. Mason Graham.[12] He proved an effective and popular leader of that institution, which would later become Louisiana State University (LSU). Colonel Joseph P. Taylor, the brother of the late President Zachary Taylor, declared that "if you had hunted the whole army, from one end of it to the other, you could not have found a man in it more admirably suited for the position in every respect than Sherman."[13]

In January 1861 just before the outbreak of the American Civil War, Sherman was required to accept receipt of arms surrendered to the State Militia by the U.S. Arsenal at Baton Rouge. Instead of complying, he resigned his position as superintendent and returned to the North, declaring to the governor of Louisiana, "On no earthly account will I do any act or think any thought hostile ... to the ... United States."[14] He became president of the St. Louis Railroad, a streetcar company, a position he held for only a few months before being called to Washington, D.C.

Civil War service

Army commission

Sherman accepted a commission as a colonel in the 13th U.S. Infantry regiment on May 14, 1861. He was one of the few Union officers to distinguish himself at the First Battle of Bull Run on July 21, where he was grazed by bullets in the knee and shoulder. The disastrous Union defeat led Sherman to question his own judgment as an officer and the capacities of his volunteer troops. President Lincoln, however, promoted him to brigadier general of volunteers (effective May 17, which ranked him senior to that of Ulysses S. Grant, his future commander).[15] He was assigned to command the Department of the Cumberland in Louisville, Kentucky.

Breakdown and Shiloh

During his time in Louisville, Sherman became increasingly pessimistic about the outlook of the war and repeatedly made estimates of the strength of the rebel forces that proved exaggerated, causing the local press to describe him as "crazy." In the fall of 1861, Sherman experienced what would probably be described today as a nervous breakdown. He was put on leave and returned to Ohio to recuperate, being replaced in his command by Don Carlos Buell. However, Sherman quickly recovered and returned to service under Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, commander of the Department of the Missouri. Halleck's department had just won a major victory at Fort Henry, but he harbored doubts about the commander in the field, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and his plans to capture Fort Donelson. Unbeknownst to Grant, Halleck offered several officers, including Sherman, command of Grant's army. Sherman refused, saying he preferred serving under Grant, even though he outranked him. Sherman wrote to Grant from Paducah, "Command me in any way. I feel anxious about you as I know the great facilities [the Confederates] have of concentration by means of the river and railroad, but [I] have faith in you."[16]

After Grant was promoted to major general in command of the District of West Tennessee, Sherman served briefly as his replacement in command of the District of Cairo. He got his wish of serving under Grant when he was assigned on March 1, 1862, to the Army of West Tennessee as commander of the 5th Division.[17] His first major test under Grant was at the Battle of Shiloh. The massive Confederate attack on the morning of April 6 took most of the senior Union commanders by surprise. Sherman in particular had dismissed the intelligence reports that he had received from militia officers, refusing to believe that Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston would leave his base at Corinth. He took no precautions beyond strengthening his picket lines, refusing to entrench, build abatis, or push out reconnaissance patrols. At Shiloh, he may have wished to avoid appearing overly alarmed in order to escape the kind of criticism he had received in Kentucky. He had written to his wife that, if he took more precautions, "they'd call me crazy again."[18]

Despite being caught unprepared by the attack, Sherman rallied his division and conducted an orderly, fighting retreat that helped avert a disastrous Union rout. Sherman would prove instrumental to the successful Union counterattack of April 7. Sherman was wounded twice —in the hand and shoulder— and had three horses shot out from under him. His performance was praised by Grant and Halleck and after the battle, he was promoted to major general of volunteers, effective May 1.[19]

Vicksburg and Chattanooga

Sherman developed close personal ties to Grant during the two years they served together. Shortly after Shiloh, Sherman persuaded Grant not to resign from the Army, despite the serious difficulties he was having with his commander, General Halleck. The careers of both officers ascended considerably after that time. Sherman later famously declared that "Grant stood by me when I was crazy and I stood by him when he was drunk and now we stand by each other always."[20]

Sherman's military record in 1862–63 was mixed. In December 1862, forces under his command suffered a severe repulse at the Battle of Chickasaw Bluffs, just north of Vicksburg. Soon after, his XV Corps was ordered to join Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand in his successful assault on Arkansas Post, generally regarded as a politically motivated distraction from the effort to capture Vicksburg.[21] Before the Vicksburg Campaign in the spring of 1863, Sherman expressed serious reservations about the wisdom of Grant's unorthodox strategy,[22] but he went on to perform well in that campaign under Grant's supervision.

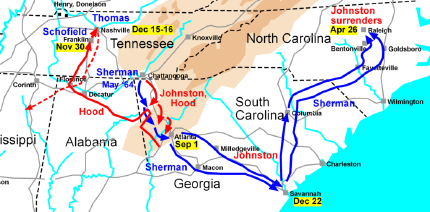

During the Battle of Chattanooga in November, Sherman, now in command of the Army of the Tennessee, quickly took his assigned target of Billy Goat Hill at the north end of Missionary Ridge, only to discover that it was not part of the ridge at all, but rather a detached spur separated from the main spine by a rock-strewn ravine. When he attempted to attack the main spine at Tunnel Hill, his troops were repeatedly repulsed by Patrick Cleburne's heavy division, the best unit in Braxton Bragg's army.[23] Sherman's effort was overshadowed by George Henry Thomas's army's successful assault on the center of the Confederate line, a movement originally intended as a diversion.

Georgia

Despite this mixed record, Sherman enjoyed Grant's confidence and friendship. When Lincoln called Grant east in the spring of 1864 to take command of all the Union armies, Grant appointed Sherman (by then known to his soldiers as "Uncle Billy") to succeed him as head of the Military Division of the Mississippi, which entailed command of Union troops in the Western Theater of the war. As Grant took command of the Army of the Potomac, Sherman wrote to him outlining his strategy to bring the war to an end concluding that "if you can whip Lee and I can march to the Atlantic I think ol' Uncle Abe will give us twenty days leave to see the young folks."[24]

Sherman proceeded to invade the state of Georgia with three armies: the 60,000-strong Army of the Cumberland under George Henry Thomas, the 25,000-strong Army of the Tennessee under James B. McPherson, and the 13,000-strong Army of the Ohio under John M. Schofield.[25] He fought a lengthy campaign of maneuver through mountainous terrain against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee, attempting a direct assault against Johnston only at the disastrous Battle of Kennesaw Mountain. The cautious Johnston was replaced by the more aggressive John Bell Hood, who played to Sherman's strength by challenging him to direct battles on open ground.

Sherman's Atlanta Campaign concluded successfully on September 2, 1864, with the capture of the city of Atlanta, an accomplishment that made Sherman a household name in the North and helped ensure Lincoln's presidential re-election in November. Lincoln's electoral defeat by Democratic Party candidate George B. McClellan, the former Union army commander, had appeared likely in the summer of that year. Such an outcome would probably have meant the victory of the Confederacy, as the Democratic Party platform called for peace negotiations based on the acknowledgement of the Confederacy's independence. Thus the capture of Atlanta, coming when it did, may have been Sherman's greatest contribution to the Union cause.

After Atlanta, Sherman dismissed the impact of Gen. Hood's attacks against his supply lines and sent George Thomas to defeat him in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. Meanwhile, declaring that he could "make Georgia howl,"[26] Sherman marched with 62,000 men to the port of Savannah, living off the land and causing, by his own estimate, more than $100 million in property damage.[27] At the end of this campaign, known as Sherman's March to the Sea, his troops captured Savannah on December 22. Sherman then telegraphed Lincoln, offering him the city as a Christmas present.

The Carolinas

In the spring of 1865, Grant ordered Sherman to embark his army on steamers to join him against Lee in Virginia. Instead, Sherman persuaded Grant to allow him to march north through the Carolinas, destroying everything of military value along the way, as he had done in Georgia. He was particularly interested in targeting South Carolina, the first state to secede from the Union, for the effect it would have on Southern morale. His army proceeded north through South Carolina against light resistance from the troops of Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston. Upon hearing that Sherman's men were advancing on corduroy roads through the Salkehatchie swamps at a rate of a dozen miles per day, Johnston declared that "there had been no such army in existence since the days of Julius Caesar."[28]

Sherman captured the state capital of Columbia on February 17 1865. Fires began that night and by next morning, most of the central city was destroyed. The burning of Columbia has engendered controversy ever since, with some claiming the fires were accidental, others a deliberate act of vengeance, and still others that the retreating Confederates burned bales of cotton on their way out of town. Thereafter, his troops did little damage to the civilian infrastructure.

Shortly after his victory over Johnston's troops at the Battle of Bentonville, Sherman met with Johnston at Bennett Place in Durham, North Carolina, to negotiate a Confederate surrender. At the insistence of Johnston and Confederate President Jefferson Davis, Sherman offered generous terms that dealt with both political and military issues, despite having no authorization to do so from either General Grant or the cabinet. The government in Washington, D.C. refused to honor the terms, precipitating a long-lasting feud between Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Confusion over this issue lasted until April 26, when Johnston, ignoring instructions from President Davis, agreed to purely military terms and formally surrendered his army and all the Confederate forces in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.[29]

Slavery and emancipation

Though he came to disapprove of chattel slavery, Sherman was not an abolitionist before the war, and like many of his time and background, he did not believe in "Negro equality."[30] His military campaigns of 1864 and 1865 freed many slaves, who greeted him "as a second Moses or Aaron"[31] and joined his marches through Georgia and the Carolinas by the tens of thousands. The precarious living conditions and uncertain future of the freed slaves quickly became a pressing issue.

On January 16, 1865, Sherman issued his Special Field Orders, No. 15. The orders provided for the settlement of 40,000 freed slaves and black refugees on land expropriated from white landowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida. Sherman appointed Brig. Gen. Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist from Massachusetts who had previously directed the recruitment of black soldiers, to implement that plan.[32] Those orders, which became the basis of the claim that the Union government had promised freed slaves "40 acres and a mule," were revoked later that year by President Andrew Johnson.

Strategies

General Sherman's record as a tactician was mixed, and his military legacy rests primarily on his command of logistics and on his brilliance as a strategist. The influential, twentieth-century, British military historian and theorist Basil Liddell Hart ranked Sherman as one of the most important strategists in the annals of war, along with Scipio Africanus, Belisarius, Napoleon Bonaparte, T.E. Lawrence, and Erwin Rommel. Liddell Hart credited Sherman with mastery of maneuver warfare (also known as the "indirect approach"), as demonstrated by his series of turning movements against Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign. Liddell Hart also stated that study of Sherman's campaigns had contributed significantly to his own "theory of strategy and tactics in mechanized warfare," which had in turn influenced Heinz Guderian's doctrine of Blitzkrieg and Rommel's use of tanks during World War II.[33]

Sherman's greatest contribution to the war, the strategy of total warfare—endorsed by General Grant and President Lincoln—has been the subject of much controversy. Sherman himself downplayed his role in conducting total war, often saying that he was simply carrying out orders as best he could in order to fulfill his part of Grant's master plan for ending the war.

Postbellum service

On July 25 1866, Congress created the rank of general of the army for Grant and promoted Sherman to lieutenant general. When Grant became president in 1869, Sherman was appointed commanding general of the U.S. Army. After the death of John A. Rawlins, Sherman also served for one month as interim Secretary of War. His tenure as commanding general was marred by political difficulties, and from 1874 to 1876, he moved his headquarters to St. Louis in an attempt to escape from them. One of his significant contributions as head of the Army was the establishment of the Command School (now the Command and General Staff College) at Fort Leavenworth.

Sherman's main concern as commanding general was to protect the construction and operation of the railroads from attack by hostile Indians. In his campaigns against the Indian tribes, Sherman repeated his Civil War strategy by seeking not only to defeat the enemy's soldiers, but also to destroy the resources that allowed the enemy to sustain its warfare. The policies he implemented included the decimation of the buffalo, which were the primary source of food for the Plains Indians.[34] Despite his harsh treatment of the warring tribes, Sherman spoke out against speculators and government agents who treated the natives unfairly within the reservations.[35]

In 1875 Sherman published his memoirs in two volumes. Then on June 19, 1879, Sherman delivered his famous "War Is Hell" speech to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy and to the gathered crowd of more than 10,000: "There is many a boy here today who looks on war as all glory, but, boys, it is all hell."[36]

Sherman stepped down as commanding general on November 1, 1883, and retired from the army on February 8, 1884. He lived most of the rest of his life in New York City. He was devoted to the theater and to amateur painting and was much in demand as a colorful speaker at dinners and banquets, in which he indulged a fondness for quoting Shakespeare.[37] Sherman was proposed as a Republican candidate for the presidential election of 1884, but declined as emphatically as possible, saying, "If nominated I will not run; if elected I will not serve."[38] Such a categorical rejection of a candidacy is now referred to as a "Shermanesque statement."

Death and posterity

Sherman died in New York City. On February 19, 1891, a small funeral was held there at his home. His body was then transported to St. Louis, where another service was conducted on February 21 at a local Catholic church. His son, Thomas Ewing Sherman, a Jesuit priest, presided over his father's funeral mass.

Sherman is buried in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis. Major memorials to Sherman include the gilded bronze equestrian statue by Augustus Saint-Gaudens at the main entrance to Central Park in New York City and the major monument by Carl Rohl-Smith near President's Park in Washington, D.C. Other posthumous tributes include the naming of the World War II M4 Sherman tank and the "General Sherman" Giant Sequoia tree, the most massive, documented, single-trunk tree in the world.

Writings

- General Sherman's Official Account of His Great March to Georgia and the Carolinas, from His Departure from Chattanooga to the Surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston and Confederate Forces under His Command (1865)

- Memoirs of General William T. Sherman, Written by Himself (1875)

- Reports of Inspection Made in the Summer of 1877 by Generals P. H. Sheridan and W. T. Sherman of Country North of the Union Pacific Railroad (co-author, 1878)

- The Sherman Letters: Correspondence between General and Senator Sherman from 1837 to 1891 (posthumous, 1894)

- Home Letters of General Sherman (posthumous, 1909)

- General W. T. Sherman as College President: A Collection of Letters, Documents, and Other Material, Chiefly from Private Sources, Relating to the Life and Activities of General William Tecumseh Sherman, to the Early Years of Louisiana State University, and the Stirring Conditions Existing in the South on the Eve of the Civil War (posthumous, 1912)

- The William Tecumseh Sherman Family Letters (posthumous, 1967)

- Sherman at War (posthumous, 1992)

- Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman, 1860 – 1865 (posthumous, 1999)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brockett, L.P., Our Great Captains: Grant, Sherman, Thomas, Sheridan, and Farragut, C.B. Richardson, 1866.

- Eicher, John H., & Eicher, David J., Civil War High Commands, Stanford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Grimsley, Mark, The Hard Hand of War: Union Military Policy toward Southern Civilians, 1861-1865, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-59941-5.

- Hanson, Victor D., The Soul of Battle, Anchor Books, 1999, ISBN 0-385-72059-9.

- Hirshson, Stanley P., The White Tecumseh: A Biography of General William T. Sherman, John Wiley & Sons, 1997, ISBN 0-471-28329-0.

- Hitchcock, Henry, Marching with Sherman: Passages from the Letters and Campaign Diaries of *Isenberg, Andrew C., The Destruction of the Bison, Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-00348-2.

- Lewis, Lloyd, Sherman: Fighting Prophet, Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1932. Reprinted in 1993 by the University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-7945-0.

- Liddell Hart, Basil Henry, Sherman: Soldier, Realist, American, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1929. Reprinted in 1993 by Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-80507-3.

- Marszalek, John F., Sherman: A Soldier's Passion for Order, Free Press, 1992, ISBN 0-02-920135-7.

- Marszalek, John F., "William Tecumseh Sherman," Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History, Heidler, David S., and Heidler, Jeanne T., eds., W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, ISBN 0-393-04758-X.

- Royster, Charles, The Destructive War: William Tecumseh Sherman, Stonewall Jackson, and the Americans, Alfred A. Knopf, 1991, ISBN 0-679-73878-9.

- Sherman's Civil War: Selected Correspondence of William T. Sherman,1860-1865, eds. B.D. Simpson and J.V. Berlin, University of North Carolina Press, 1999, ISBN 0-8078-2440-2.

- Sherman, William T., Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by the Library of America, 1990, ISBN 0-940450-65-8.

- "William Tecumseh Sherman," A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, Vol. II (1988), p. 741.

- Smith, Jean Edward, Grant, Simon and Shuster, 2001, ISBN 0-684-84927-5.

- Warner, Ezra J., Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders, LSU Press, 1964, ISBN 0-8071-0822-7.

- Woodward, C. Vann, "Civil Warriors," New York Review of Books, vol. 37, no. 17, Nov. 8, 1990.

Notes

- ↑ Liddell Hart, p. 430

- ↑ See, William T. Sherman papers, Notre Dame University CSHR 19/67 Folder:Roger Sherman's Watch 1932-1942

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 14

- ↑ Quoted in Hirshson, p. 13

- ↑ See, for instance, Hirshson, p. 21

- ↑ See Sherman at the Virtual Museum of San Francisco and excerpts from Sherman's Memoirs

- ↑ See, for instance, Hirshson, pp. 362-368, 387

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 125-129

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, pp. 131-134, 166

- ↑ Quoted in Royster, pp. 133-134

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 158-160

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, Chap. VI

- ↑ Quoted in Hirshson, p. 68

- ↑ Letter by W.T. Sherman to Gov. Thomas O. Moore, Jan. 18, 1861. Quoted in Sherman, Memoirs, p. 156

- ↑ See, for instance, Hirshson, pp. 90-94

- ↑ Smith, pp, 151-52

- ↑ Eicher, p. 485

- ↑ Daniel, p. 138

- ↑ Eicher, p. 485

- ↑ Brockett, p. 175

- ↑ Smith, p. 227

- ↑ Smith, pp. 235-36

- ↑ McPherson, p. 678

- ↑ Sherman, Memoirs, p. 589

- ↑ McPherson, p. 653

- ↑ Telegram by W.T. Sherman to Gen. U.S. Grant, Oct. 9, 1864, reproduced in Sherman's Civil War, pp. 731-732

- ↑ Report by Maj. Gen. W.T. Sherman, Jan. 1, 1865, quoted in Grimsley, p. 200

- ↑ Quoted in McPherson, p. 727

- ↑ See, for instance, Johnston's Surrender at Bennett Place on Hillsboro Road

- ↑ See, for instance, letter by W.T. Sherman to Salmon P. Chase, Jan. 11, 1865, reproduced in Sherman's Civil War, pp. 794-795, and letter by W.T. Sherman to John Sherman, Aug. 1865, quoted in Liddell Hart, p. 406

- ↑ Letter to Chase, cited above

- ↑ Special Field Orders, No. 15, Jan. 16, 1865. See also McPherson, pp. 737-739

- ↑ Liddell Hart, foreword to the Indiana University Press's edition of Sherman's Memoirs (1957). Quoted in Wilson, p. 179

- ↑ See Isenberg, pp. 128, 156

- ↑ See, for instance, Lewis, pp. 597-600

- ↑ From transcript published in the Ohio State Journal, August 12, 1880, reproduced in Lewis, p. 637

- ↑ See, for instance, Woodward

- ↑ Marszalek, William Tecumseh Sherman, p. 1769.

External links

- U.S. Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- William Tecumseh Sherman, from the Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco, concentrates on Sherman's time in California. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- General William Tecumseh Sherman, from About North Georgia, concentrates on Sherman's time in Georgia. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- Sherman House Museum, at Sherman's birthplace in Lancaster, Ohio. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- St. Louis Walk of Fame. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman. Retrieved 2.23.07.

- Works by William Tecumseh Sherman. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2.23.07.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.