Difference between revisions of "Vanilla" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

[[Image:Vanilla 6beans.JPG|right|200px|thumb|Vanilla pods]] | [[Image:Vanilla 6beans.JPG|right|200px|thumb|Vanilla pods]] | ||

'''Vanilla''' is the common name and [[genus]] name for a group of [[vine]]-like, [[evergreen]], tropical and sub-tropical plants in the orchid family ([[Orchidaceae]]), including the commercially important species ''Vanilla planifolia'' from whose seedpods a popular flavoring extract is derived. The term also is used for the long, narrow seedpods of ''V. planifolia'' (also called vanilla bean) and for the flavoring agent derived from the cured seedpods or synthetically produced. | '''Vanilla''' is the common name and [[genus]] name for a group of [[vine]]-like, [[evergreen]], tropical and sub-tropical plants in the orchid family ([[Orchidaceae]]), including the commercially important species ''Vanilla planifolia'' from whose seedpods a popular flavoring extract is derived. The term also is used for the long, narrow seedpods of ''V. planifolia'' (also called vanilla bean) and for the flavoring agent derived from the cured seedpods or synthetically produced. | ||

| + | |||

| + | notes: The process for obtaining pure vanilla is very time consuming and labor intensive, involving hand pollination, about six weeks for the pods to reach full size, eight to nine months after that to mature, hand picking of the mature pods, and a three to six month process for curing (Herbst 2001). The curing process involves a boiling-water bath, sun heating, wrapping and allowing the beans to sweat, and so forth. Over months of drying in the sun during the day and sweating at night, they shrink by 400 percent and turn a characteristic dark brown (Herbst 2001). And to make it even more remarkable, the flower is open only one day a year, and perhaps for a few hours (Herbst 2001). The following is more detail on this process. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

The name came from the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] word "{{lang|es|vainilla}}," meaning "little pod" (Ackerman 2003). Vanilla is valued for its sweet flavor and scent and is widely used in the preparation of [[dessert]]s and [[perfume]]s. | The name came from the [[Spanish language|Spanish]] word "{{lang|es|vainilla}}," meaning "little pod" (Ackerman 2003). Vanilla is valued for its sweet flavor and scent and is widely used in the preparation of [[dessert]]s and [[perfume]]s. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 23: | ||

| tribus = Vanilleae | | tribus = Vanilleae | ||

| subtribus = Vanillinae | | subtribus = Vanillinae | ||

| − | | genus = '''''Vanilla''''' (Plumier ex. [[Philip Miller|Mill.]], | + | | genus = '''''Vanilla''''' (Plumier ex. [[Philip Miller|Mill.]], 1754) |

| subdivision_ranks = Species | | subdivision_ranks = Species | ||

| subdivision = | | subdivision = | ||

About 110 species | About 110 species | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | ''Vanilla'' is a [[genus]] of about 110 species in the [[orchid]] family ([[Orchidaceae]]). Orchidaceae is the largest and most diverse of the [[flowering plant]] families, with over eight hundred described | + | ''Vanilla'' is a [[genus]] of about 110 species in the [[orchid]] family ([[Orchidaceae]]). Orchidaceae is the largest and most diverse of the [[flowering plant]] families, with over eight hundred described genera and 25,000 [[species]]. There are also over 100,000 hybrids and cultivars produced by horticulturalists, created since the introduction of tropical species to Europe. |

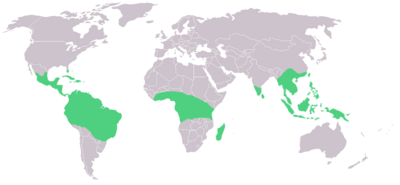

The evergreen genus ''Vanilla'' occurs worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, from tropical America to tropical Asia, New Guinea, and West Africa. It was known to the [[Aztec]]s for its flavoring qualities. It is also grown commercially (esp. ''Vanilla planifolia'', ''Vanilla pompona'' and ''Vanilla tahitensis''). | The evergreen genus ''Vanilla'' occurs worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, from tropical America to tropical Asia, New Guinea, and West Africa. It was known to the [[Aztec]]s for its flavoring qualities. It is also grown commercially (esp. ''Vanilla planifolia'', ''Vanilla pompona'' and ''Vanilla tahitensis''). | ||

| Line 51: | Line 55: | ||

[[Image:Map Vanilla.png|thumb|centre|400px|Worldwide distribution of ''Vanilla'' species.]] | [[Image:Map Vanilla.png|thumb|centre|400px|Worldwide distribution of ''Vanilla'' species.]] | ||

| − | |||

===''Vanilla planifolia=== | ===''Vanilla planifolia=== | ||

| Line 59: | Line 62: | ||

Like all members of the ''Vanilla'' genus, Vanilla planifolia is a vine. It uses its fleshy roots to support itself as it grows. | Like all members of the ''Vanilla'' genus, Vanilla planifolia is a vine. It uses its fleshy roots to support itself as it grows. | ||

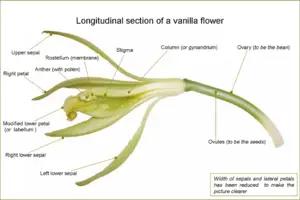

| − | Flowers are greenish-yellow, with a diameter of 5 centimeters (2 in). They last only a day. | + | Flowers are greenish-yellow, with a diameter of 5 centimeters (2 in). They last only a day. |

| + | |||

| + | ''Vanilla planifolia'' flowers are [[hermaphroditic]], carrying both male ([[anther]]) and female ([[pistil|stigma]]) organs. [[Pollination]] simply requires a transfer of the pollen from the [[anther]] to the [[stigma]]. However, [[self-pollination]] is avoided by a membrane separating these organs. As [[Charles François Antoine Morren]], a Belgian botanist found, the flowers can only be naturally pollinated by a specific Melipone bee found in Mexico. | ||

| + | |||

| + | If pollination does not occur, the flower is dropped the next day. In the wild, there is less than 1% chance that the flowers will be pollinated, so in order to receive a steady flow of fruit, the flowers must be hand-pollinated when grown on farms. | ||

Fruit is produced only on mature plants, which are generally over 3 meters (10 feet) long. The fruits are 15-23 centimeters (6-9 inches) long pods (often incorrectly called beans). They mature after about five months, at which point they are harvested and [[curing (food preservation)|cured]]. Curing ferments and dries the pods while minimizing the loss of [[essential oil]]s. Vanilla extract is obtained from this portion of the plant. | Fruit is produced only on mature plants, which are generally over 3 meters (10 feet) long. The fruits are 15-23 centimeters (6-9 inches) long pods (often incorrectly called beans). They mature after about five months, at which point they are harvested and [[curing (food preservation)|cured]]. Curing ferments and dries the pods while minimizing the loss of [[essential oil]]s. Vanilla extract is obtained from this portion of the plant. | ||

| Line 71: | Line 78: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | The first to cultivate vanilla were the [[Totonac]] people | + | The first to cultivate vanilla were the [[Totonac]] people. The Totonac people resided in the eastern coastal and mountainous regions of [[Mexico]] at the time of the Spanish arrival in 1519. (Today they reside in the [[Mexican state|states]] of [[Veracruz]], [[Puebla]], and [[Hidalgo (state)|Hidalgo]].) They built the [[Pre-Columbian]] city of [[El Tajín]], and further maintained quarters in [[Teotihuacán]] (a city which they claim to have built). Until the mid-19th century, they were the world's main producers of vanilla. |

| + | |||

| + | According to Totonac mythology, the tropical orchid was born when Princess Xanat, forbidden by her father from marrying a mortal, fled to the forest with her lover. The lovers were captured and beheaded. Where their blood touched the ground, the vine of the tropical orchid grew (Hazen 1995). | ||

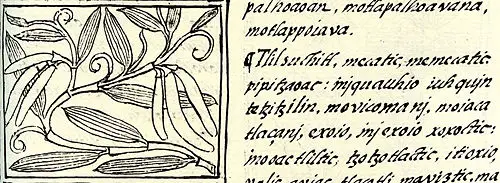

[[Image:Vanilla florentine codex.jpg|500px|right|thumb| Drawing of Vanilla from the [[Florentine Codex]] (ca. 1580) and description of its use and properties written in the [[Nahuatl]] language.]] | [[Image:Vanilla florentine codex.jpg|500px|right|thumb| Drawing of Vanilla from the [[Florentine Codex]] (ca. 1580) and description of its use and properties written in the [[Nahuatl]] language.]] | ||

| − | In the fifteenth century, [[Aztec]]s from the central highlands of Mexico conquered the Totonacs, and the conquerors soon developed a taste for the vanilla bean. They named the bean ''tlilxochitl'', or "black flower" | + | In the fifteenth century, [[Aztec]]s from the central highlands of Mexico conquered the Totonacs, and the conquerors soon developed a taste for the vanilla bean. They named the bean ''tlilxochitl'', or "black flower," after the mature bean, which shrivels and turns black shortly after it is picked. After they were subjected to the Aztecs, the Totonacs paid their tribute by sending vanilla beans to the Aztec capital, [[Tenochtitlan]]. |

| − | Vanilla was completely unknown in the Old World before Columbus. | + | Vanilla was completely unknown in the Old World before Columbus. Spanish explorers who arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the early sixteenth century gave vanilla its name. The Spanish and Portuguese sailors and explorers brought vanilla into Africa and Asia in the 16th century. They called it ''vainilla,'' or "little pod." The word ''vanilla'' entered the English language in the 1754, when the botanist [[Philip Miller]] wrote about the genus in his ''Gardener’s Dictionary'' (Correll 1953). |

| − | Spanish explorers who arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the early sixteenth century gave vanilla its name. The Spanish and Portuguese sailors and explorers brought vanilla into Africa and Asia in the 16th century. They called it ''vainilla,'' or "little pod" | ||

| − | Until the mid-[[19th century]], Mexico was the chief producer of vanilla. In 1819, however, [[France|French]] entrepreneurs shipped vanilla beans to the [[Réunion]] and [[Mauritius]] islands with the hope of producing vanilla there. After [[Edmond Albius]], a 12-year-old slave from Réunion Island, discovered how to pollinate the flowers quickly by hand, the pods began to thrive. Soon the tropical orchids were sent from Réunion Island to the [[Comoros Islands]] and [[Madagascar]] along with instructions for pollinating them. By 1898, Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros Islands produced 200 metric tons of vanilla beans, about 80 percent of world production | + | Until the mid-[[19th century]], Mexico was the chief producer of vanilla. In 1819, however, [[France|French]] entrepreneurs shipped vanilla beans to the [[Réunion]] and [[Mauritius]] islands with the hope of producing vanilla there. After [[Edmond Albius]], a 12-year-old slave from Réunion Island, discovered how to pollinate the flowers quickly by hand, the pods began to thrive. Soon the tropical orchids were sent from Réunion Island to the [[Comoros Islands]] and [[Madagascar]] along with instructions for pollinating them. By 1898, Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros Islands produced 200 metric tons of vanilla beans, about 80 percent of world production (Rasoanaivo et al. 1998). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The market price of vanilla rose dramatically in the late 1970s, due to a [[typhoon]]. Prices stayed stable at this level through the early 1980s despite the pressure of recently introduced Indonesian vanilla. In the mid-1980s, the [[cartel]] that had controlled vanilla prices and distribution since its creation in 1930 disbanded. Prices dropped 70 percent over the next few years, to nearly US$20 per kilo. This changed, due to typhoon Huddah, which struck early in the year 2000. The typhoon, political instability, and poor weather in the third year drove vanilla prices to an astonishing US$500 per kilo in 2004, bringing new countries into the vanilla industry. A good crop, coupled with decreased demand caused by the production of imitation vanilla, pushed the market price down to the $40 per kilo range in the middle of 2005. | ||

==Cultivation and production== | ==Cultivation and production== | ||

| Line 123: | Line 128: | ||

| {{ZIM}} || align="right" | 3 || | | {{ZIM}} || align="right" | 3 || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | |colspan="3" style="font-size:90%;"|''Source: <br>[[FAO|UN Food & Agriculture Organization]] ''[http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567] | + | |colspan="3" style="font-size:90%;"|''Source: <br/>[[FAO|UN Food & Agriculture Organization]] ''[http://faostat.fao.org/site/567/DesktopDefault.aspx?PageID=567] |

|} | |} | ||

| − | |||

| − | Vanilla grows as a [[vine]], climbing up an existing tree, pole, or other support. It can be grown in a wood (on trees), in a plantation (on trees or poles), or in a "shader" | + | Madagascar (mostly the fertile region of Sava) accounts for half of the global production of vanilla. Mexico, once the leading producer of natural vanilla with an annual 500 tons, produced only 10 tons of vanilla in 2006. An estimated 95% of “vanilla” products actually contain artificial [[vanillin]], produced from [[lignin]](RVCA). |

| + | |||

| + | The main species harvested for [[vanillin]] is ''Vanilla planifolia''. Although it is native to [[Mexico]], it is now widely grown throughout the tropics. Additional sources include ''Vanilla pompona'' and ''Vanilla tahitiensis'' (grown in [[Tahiti]]), although the vanillin content of these species is much less than ''Vanilla planifolia''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Vanilla grows as a [[vine]], climbing up an existing tree, pole, or other support. It can be grown in a wood (on trees), in a plantation (on trees or poles), or in a "shader," in increasing orders of productivity. Left alone, it will grow as high as possible on the support, with few flowers. Every year, growers fold the higher parts of the plant downwards so that the plant stays at heights accessible by a standing human. This also greatly stimulates flowering. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The process for obtaining pure vanilla is very time consuming and labor intensive, involving hand pollination, about six weeks for the pods to reach full size, eight to nine months after that to mature, hand picking of the mature pods, and a three to six month process for curing (Herbst 2001). The curing process involves a boiling-water bath, sun heating, wrapping and allowing the beans to sweat, and so forth. Over months of drying in the sun during the day and sweating at night, they shrink by 400 percent and turn a characteristic dark brown (Herbst 2001). And to make it even more remarkable, the flower is open only one day a year, and perhaps for a few hours (Herbst 2001). The following is more detail on this process. | ||

[[Image:VanillaFlowerLongitudinalSection-en.png|thumb|left|''Vanilla planifolia'' - flower.]] | [[Image:VanillaFlowerLongitudinalSection-en.png|thumb|left|''Vanilla planifolia'' - flower.]] | ||

| − | The distinctively | + | The distinctively flavored compounds are found in the fruit, which results from the [[pollination]] of the flower. One flower produces one fruit. There is only one natural pollinator, the Melipona bee, which is found in Mexico (Herbst 2001). Growers have tried to bring this bee into other growing locales, to no avail. The only way to produce fruits is thus [[pollination management|artificial pollination]]. Hand pollinators can pollinate about 1,000 flowers per day. |

| − | + | The simple and efficient artificial [[hand pollination|pollination method]] introduced in 1841 by the 12-year-old slave named [[Edmond Albius]] on [[Réunion]] is still used today. Using a beveled sliver of bamboo, an agricultural worker folds back the membrane separating the anther and the stigma, then presses the anther on the stigma. The flower is then self-pollinated, and will produce a fruit. The vanilla flower lasts about one day, sometimes less, thus growers have to inspect their plantations every day for open flowers, a labor-intensive task. | |

| − | The [[fruit]] (a seed capsule), if left on the plant, will ripen and open at the end; it will then release the distinctive vanilla smell. The fruit contains tiny, | + | The [[fruit]] (a seed capsule), if left on the plant, will ripen and open at the end; it will then release the distinctive vanilla smell. The fruit contains tiny, flavorless seeds. In dishes prepared with whole natural vanilla, these seeds are recognizable as black specks. |

Like other orchids' seeds, vanilla seed will not germinate without the presence of certain [[Orchid mycorrhiza|mycorrhizal]] [[fungi]]. Instead, growers reproduce the plant by [[cutting (plant)|cutting]]: they remove sections of the vine with six or more leaf nodes, a root opposite each leaf. The two lower leaves are removed, and this area is buried in loose soil at the base of a support. The remaining upper roots will cling to the support, and often grow down into the soil. Growth is rapid under good conditions. | Like other orchids' seeds, vanilla seed will not germinate without the presence of certain [[Orchid mycorrhiza|mycorrhizal]] [[fungi]]. Instead, growers reproduce the plant by [[cutting (plant)|cutting]]: they remove sections of the vine with six or more leaf nodes, a root opposite each leaf. The two lower leaves are removed, and this area is buried in loose soil at the base of a support. The remaining upper roots will cling to the support, and often grow down into the soil. Growth is rapid under good conditions. | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:Vanilla plantation in wood dsc00190.jpg|thumb|right|160px|A vanilla plantation in a wood on [[Réunion Island]]]] | [[Image:Vanilla plantation in wood dsc00190.jpg|thumb|right|160px|A vanilla plantation in a wood on [[Réunion Island]]]] | ||

| + | The basic production method is as follows: | ||

#'''Harvest''' | #'''Harvest''' | ||

| − | #: The pods are harvested while green and immature. At this stage, they are | + | #: The pods are harvested while green and immature. At this stage, they are odorless. |

# '''Killing''' | # '''Killing''' | ||

#: The vegetative tissue of the vanilla pod is killed to prevent further growing. The method of killing varies, but may be accomplished by sun killing, oven killing, hot water killing, killing by scratching, or killing by freezing. | #: The vegetative tissue of the vanilla pod is killed to prevent further growing. The method of killing varies, but may be accomplished by sun killing, oven killing, hot water killing, killing by scratching, or killing by freezing. | ||

# '''Sweating''' | # '''Sweating''' | ||

| − | #: The pods are held for 7 to 10 days under hot (45º-65°C or 115º-150°F) and humid conditions; pods are often placed into fabric covered boxes immediately after boiling. This allows enzymes to process the compounds in the pods into vanillin and other compounds important to the final vanilla | + | #: The pods are held for 7 to 10 days under hot (45º-65°C or 115º-150°F) and humid conditions; pods are often placed into fabric covered boxes immediately after boiling. This allows enzymes to process the compounds in the pods into vanillin and other compounds important to the final vanilla flavor. |

# '''Drying''' | # '''Drying''' | ||

#: To prevent rotting and to lock the aroma in the pods, the pods are dried. Often, pods are laid out in the sun during the mornings and returned to their boxes in the afternoons. When 25-30% of the pods' weight is moisture (as opposed to the 60-70% they began drying with) they have completed the curing process and will exhibit their fullest aromatic qualities. | #: To prevent rotting and to lock the aroma in the pods, the pods are dried. Often, pods are laid out in the sun during the mornings and returned to their boxes in the afternoons. When 25-30% of the pods' weight is moisture (as opposed to the 60-70% they began drying with) they have completed the curing process and will exhibit their fullest aromatic qualities. | ||

# '''Grading''' | # '''Grading''' | ||

#: Once fully cured, the vanilla is sorted by quality and graded. | #: Once fully cured, the vanilla is sorted by quality and graded. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

There are three main commercial preparations of natural vanilla: | There are three main commercial preparations of natural vanilla: | ||

* whole pod | * whole pod | ||

| − | * powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch or other ingredients) | + | * powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch or other ingredients) (The [[Food and Drug Administration|U.S. Food and Drug Administration]] requires at least 12.5% of pure vanilla (ground pods or oleoresin) in the mixture (FDA 1993).) |

| − | * extract (in alcoholic solution) | + | * extract (in alcoholic solution). (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 35% vol. of alcohol and 13.35 ounces of pod per gallon (FDA 2007).) |

===Specific types of vanilla=== | ===Specific types of vanilla=== | ||

| Line 177: | Line 183: | ||

Good quality vanilla has a strong aromatic flavour, but food with small amounts of low quality vanilla or artificial vanilla-like flavourings are far more common, since true vanilla is much more expensive. | Good quality vanilla has a strong aromatic flavour, but food with small amounts of low quality vanilla or artificial vanilla-like flavourings are far more common, since true vanilla is much more expensive. | ||

| − | A major use of vanilla is in flavouring [[ice cream]]. The most common flavour of ice cream is vanilla, and thus most people consider it to be the "default" flavour. By analogy, the term "vanilla" is sometimes used as a synonym for "plain" | + | A major use of vanilla is in flavouring [[ice cream]]. The most common flavour of ice cream is vanilla, and thus most people consider it to be the "default" flavour. By analogy, the term "vanilla" is sometimes used as a synonym for "plain." |

The [[cosmetics]] industry uses vanilla to make [[perfume]]. | The [[cosmetics]] industry uses vanilla to make [[perfume]]. | ||

| Line 186: | Line 192: | ||

In old medicinal literature, vanilla is described as an [[aphrodisiac]] and a remedy for [[fever]]s. These purported uses have never been scientifically proven, but it has been shown that vanilla does increase levels of catecholamines (including epinephrine, more commonly known as adrenaline), and as such can also be considered mildly addictive.<ref>http://www.organicmd.org/faq.html[http://www.organicmd.org/faq.html]</ref><ref>http://wwwwww.nwcr.ws/adam/healthillustratedencyclopedia/1/003561.html[http://wwwwww.nwcr.ws/adam/healthillustratedencyclopedia/1/003561.html]</ref> | In old medicinal literature, vanilla is described as an [[aphrodisiac]] and a remedy for [[fever]]s. These purported uses have never been scientifically proven, but it has been shown that vanilla does increase levels of catecholamines (including epinephrine, more commonly known as adrenaline), and as such can also be considered mildly addictive.<ref>http://www.organicmd.org/faq.html[http://www.organicmd.org/faq.html]</ref><ref>http://wwwwww.nwcr.ws/adam/healthillustratedencyclopedia/1/003561.html[http://wwwwww.nwcr.ws/adam/healthillustratedencyclopedia/1/003561.html]</ref> | ||

| − | In an in-vitro test vanilla was able to block [[quorum sensing]] in bacteria. | + | In an in-vitro test vanilla was able to block [[quorum sensing]] in bacteria. This is medically interesting because in many bacteria quorum sensing signals function as a switch for virulence. The microbes only become virulent when the signals indicate that they have the numbers to resist the host immune system response.<ref>{{cite journal |

| last = | | last = | ||

| first = | | first = | ||

| Line 208: | Line 214: | ||

<gallery> | <gallery> | ||

Image:Vanilla plantation dsc01187.jpg|A vanilla plantation in open field on Réunion. | Image:Vanilla plantation dsc01187.jpg|A vanilla plantation in open field on Réunion. | ||

| − | Image:Vanilla plantation in shader dsc01168.jpg|A vanilla plantation in a "shader" | + | Image:Vanilla plantation in shader dsc01168.jpg|A vanilla plantation in a "shader" ''(ombrière)'' on Réunion. |

Image:Vanilla_planifolia_1.jpg|Flower | Image:Vanilla_planifolia_1.jpg|Flower | ||

Image:Vanilla fragrans 2.jpg|Green fruits | Image:Vanilla fragrans 2.jpg|Green fruits | ||

| Line 221: | Line 227: | ||

* Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. ''A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612. | * Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. ''A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612. | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref>Correll D (1953) Vanilla: its botany, history, cultivation and economic importance. Econ Bo 7(4): 291–358.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1993. [http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=169.179 Part 169: Food dressings and flavorings. Subpart A—General provisions. Subpart B—Requirements for specific standardized food dressings and flavorings. Sec. 169.179. Vanilla powder.]. 21CFR169.179. ''Center for Devices and Radiological Health''. Retrieved April 11, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2007. [http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/CFRSearch.cfm?fr=169.3 Part 169: Food dressings and flavorings. Subpart A&mdsh;General provisions. Sec. 169.3 Definitions]. 21CFR169.3. ''Center for Devices and Radiological Health''. Retrieved April 11, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Havkin-Frenkel, D., J. C. French, N. M. Graft, F. E. Pak, C. Frenkel, and D. M. Joel. 2004. [<ref>http://www.baktoflavors.com/pdf/vanilla%20dafna%20ishs.pdf Interrelation of curing and botany in vanilla ''(Vanilla planifolia)'' bean]. ''Acta Hort.'' 629: 93-102. (L. E. Craker et al., eds., ''Proc. XXVI IHC—Future for Medicinal and Aromatic Plants''). Retrieved April 11, 2008. | ||

| + | |||

| + | .<ref>Hazen J (1995) ''Vanilla.'' Chronicle Books. San Francisco, CA.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

* Herbst, S. T. 2001. ''The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide.'' Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764112589. | * Herbst, S. T. 2001. ''The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide.'' Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764112589. | ||

| − | * | + | * Rainforest Vanilla Conservation Association. n.d. [http://vanillaexchange.com/RVCA_Handout.htm Global warming and artificial vanillin]. ''Rainforest Vanilla Conservation Association''. Retrieved April 11, 2008. |

| + | <ref>Rasoanaivo P et al (1998) Essential oils of economic value in Madagascar: Present state of knowledge. ''HerbalGram'' 43:31–39,58–59.</ref> | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| Line 231: | Line 249: | ||

*[http://www.kew.org/epic/index.htm Electronic Plant Information Centre at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2003-11-8] | *[http://www.kew.org/epic/index.htm Electronic Plant Information Centre at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2003-11-8] | ||

*[http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=27 ''Spices'' at UCLA History & Special Collections] | *[http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm?displayID=27 ''Spices'' at UCLA History & Special Collections] | ||

| − | *[http://www.uni-graz.at/~katzer/engl/Vani_pla.html Spice | + | *[http://www.uni-graz.at/~katzer/engl/Vani_pla.html Spice Pages—Vanilla] |

*[http://buy-bourbon-madagascar-vanilla-beans-europe.riziky.be/did-you-know.php Did you know?] | *[http://buy-bourbon-madagascar-vanilla-beans-europe.riziky.be/did-you-know.php Did you know?] | ||

*[https://www.vanilla-trade.com/index.php?main_page=page_2 Mexican Gourmet Vanilla: History] | *[https://www.vanilla-trade.com/index.php?main_page=page_2 Mexican Gourmet Vanilla: History] | ||

| Line 239: | Line 257: | ||

[[Category:Plants]] | [[Category:Plants]] | ||

| − | {{credit|Vanilla|204773272|Vanilla_(genus)|204872918|Vanilla_planifolia|194597857}} | + | {{credit|Vanilla|204773272|Vanilla_(genus)|204872918|Vanilla_planifolia|194597857|Totonac|203389965}} |

Revision as of 01:53, 12 April 2008

Vanilla is the common name and genus name for a group of vine-like, evergreen, tropical and sub-tropical plants in the orchid family (Orchidaceae), including the commercially important species Vanilla planifolia from whose seedpods a popular flavoring extract is derived. The term also is used for the long, narrow seedpods of V. planifolia (also called vanilla bean) and for the flavoring agent derived from the cured seedpods or synthetically produced.

notes: The process for obtaining pure vanilla is very time consuming and labor intensive, involving hand pollination, about six weeks for the pods to reach full size, eight to nine months after that to mature, hand picking of the mature pods, and a three to six month process for curing (Herbst 2001). The curing process involves a boiling-water bath, sun heating, wrapping and allowing the beans to sweat, and so forth. Over months of drying in the sun during the day and sweating at night, they shrink by 400 percent and turn a characteristic dark brown (Herbst 2001). And to make it even more remarkable, the flower is open only one day a year, and perhaps for a few hours (Herbst 2001). The following is more detail on this process.

The name came from the Spanish word "vainilla," meaning "little pod" (Ackerman 2003). Vanilla is valued for its sweet flavor and scent and is widely used in the preparation of desserts and perfumes.

Vanilla genus

| Vanilla Orchid | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Vanilla planifolia

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

About 110 species |

Vanilla is a genus of about 110 species in the orchid family (Orchidaceae). Orchidaceae is the largest and most diverse of the flowering plant families, with over eight hundred described genera and 25,000 species. There are also over 100,000 hybrids and cultivars produced by horticulturalists, created since the introduction of tropical species to Europe.

The evergreen genus Vanilla occurs worldwide in tropical and subtropical regions, from tropical America to tropical Asia, New Guinea, and West Africa. It was known to the Aztecs for its flavoring qualities. It is also grown commercially (esp. Vanilla planifolia, Vanilla pompona and Vanilla tahitensis).

This genus of vine-like plants has a monopodial climbing habit. They can form long vines with a length of more than 35 meters, with alternate leaves spread along its length. The short, oblong, dark green leaves of the Vanilla are thick and leathery, even fleshy in some species, though there are a significant number of species that have their leaves reduced to scales or have become nearly or totally leafless and appear to use their green climbing stems for photosynthesis. Long and strong aerial roots grow from each node.

The racemose inflorescences short-lived flowers arise successively on short peduncles from the leaf axils or scales. There may be up to 100 flowers on a single raceme, but usually no more than 20. The flowers are quite large and attractive with white, green, greenish yellow, or cream colors. Their sepals and petals are similar. Each flower opens up in the morning and closes late in the afternoon, never to re-open. If pollination has not occurred meanwhile, it will be shed.

The lip is tubular-shaped and surrounds the long, bristly column, opening up, as the bell of a trumpet, at its apex. The anther is at the top of the column and hangs over the stigma, separated by the rostellum. Blooming occurs only when the flowers are fully grown. Most species have a sweet scent. The flowers are self-fertile but need pollinators to perform this task. The flowers are presumed to be pollinated by stingless bees and certain hummingbirds, which visit the flowers primarily for its nectar. But hand pollination is the best method in commercially grown Vanilla.

The fruit ('vanilla bean') is an elongate, fleshy seed pod 10-25 centimeters long. It ripens gradually (8 to 9 months after flowering), eventually turning black in color and giving off a strong aroma. Each pod contains thousands of minute seeds, but it is the pod that is used to create vanilla flavoring. Significantly, Vanilla planifolia is the only orchid used for industrial purposes (in the food industry and in the cosmetic industry).

Species, with common names, include:

- Vanilla aphylla: Leafless Vanilla

- Vanilla barbellata: Small Bearded Vanilla, Wormvine Orchid, Leafless Vanilla, Snake Orchid.

- Vanilla chamissonis: Chamisso's Vanilla

- Vanilla claviculata: Green Withe

- Vanilla dilloniana: Leafless Vanilla

- Vanilla edwallii: Edwall's Vanilla

- Vanilla mexicana: Mexican Vanilla

- Vanilla odorata: Inflated Vanilla

- Vanilla phaeantha: Leafy Vanilla

- Vanilla planifolia: Vanilla, Flat-plane Leaved Vanilla, West Indian Vanilla

- Vanilla poitaei: Poiteau's Vanilla

- Vanilla siamensis: Thai Vanilla

Vanilla planifolia

Vanilla planifolia (synonym Vanilla fragrans) is one of the primary sources for vanilla flavoring, due to its high vanillin content. Vanilla planifolia is found in Central America and the West Indies. It prefers hot, wet, tropical climates. It is harvested mostly in Mexico and Madagascar. Of the over 25,000 species of orchids, V. planifolia is the only one that is known to bear anything edible, the vanilla "bean" (Herbst 2001).

Like all members of the Vanilla genus, Vanilla planifolia is a vine. It uses its fleshy roots to support itself as it grows.

Flowers are greenish-yellow, with a diameter of 5 centimeters (2 in). They last only a day.

Vanilla planifolia flowers are hermaphroditic, carrying both male (anther) and female (stigma) organs. Pollination simply requires a transfer of the pollen from the anther to the stigma. However, self-pollination is avoided by a membrane separating these organs. As Charles François Antoine Morren, a Belgian botanist found, the flowers can only be naturally pollinated by a specific Melipone bee found in Mexico.

If pollination does not occur, the flower is dropped the next day. In the wild, there is less than 1% chance that the flowers will be pollinated, so in order to receive a steady flow of fruit, the flowers must be hand-pollinated when grown on farms.

Fruit is produced only on mature plants, which are generally over 3 meters (10 feet) long. The fruits are 15-23 centimeters (6-9 inches) long pods (often incorrectly called beans). They mature after about five months, at which point they are harvested and cured. Curing ferments and dries the pods while minimizing the loss of essential oils. Vanilla extract is obtained from this portion of the plant.

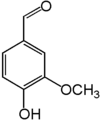

Vanillin and other compounds

The compound vanillin (4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde) is the primary agent responsible for the characteristic flavor and smell of vanilla. There also are many other compounds present in the extracts of vanilla that aid the flavor. Another minor component of vanilla essential oil is piperonal (heliotropin). Piperonal and other substances affect the odor of natural vanilla.

Vanilla essence comes in two forms. Real seedpod extract is an extremely complicated mixture of several hundred different compounds. Synthetic essence, consisting basically of a solution of synthetic vanillin in ethanol, is derived from phenol and is of high purity (Havkin-Frenkel 2004). The synthetic vanillin, ethyl vanillin, which does not occur in the vanilla bean, as patented by German chemist Ferdinand Tiemann in 1875 and has over three times the flavor and more storage stability, although it lacks the true flavor (Bender and Bender 2005).

History

The first to cultivate vanilla were the Totonac people. The Totonac people resided in the eastern coastal and mountainous regions of Mexico at the time of the Spanish arrival in 1519. (Today they reside in the states of Veracruz, Puebla, and Hidalgo.) They built the Pre-Columbian city of El Tajín, and further maintained quarters in Teotihuacán (a city which they claim to have built). Until the mid-19th century, they were the world's main producers of vanilla.

According to Totonac mythology, the tropical orchid was born when Princess Xanat, forbidden by her father from marrying a mortal, fled to the forest with her lover. The lovers were captured and beheaded. Where their blood touched the ground, the vine of the tropical orchid grew (Hazen 1995).

In the fifteenth century, Aztecs from the central highlands of Mexico conquered the Totonacs, and the conquerors soon developed a taste for the vanilla bean. They named the bean tlilxochitl, or "black flower," after the mature bean, which shrivels and turns black shortly after it is picked. After they were subjected to the Aztecs, the Totonacs paid their tribute by sending vanilla beans to the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan.

Vanilla was completely unknown in the Old World before Columbus. Spanish explorers who arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico in the early sixteenth century gave vanilla its name. The Spanish and Portuguese sailors and explorers brought vanilla into Africa and Asia in the 16th century. They called it vainilla, or "little pod." The word vanilla entered the English language in the 1754, when the botanist Philip Miller wrote about the genus in his Gardener’s Dictionary (Correll 1953).

Until the mid-19th century, Mexico was the chief producer of vanilla. In 1819, however, French entrepreneurs shipped vanilla beans to the Réunion and Mauritius islands with the hope of producing vanilla there. After Edmond Albius, a 12-year-old slave from Réunion Island, discovered how to pollinate the flowers quickly by hand, the pods began to thrive. Soon the tropical orchids were sent from Réunion Island to the Comoros Islands and Madagascar along with instructions for pollinating them. By 1898, Madagascar, Réunion, and the Comoros Islands produced 200 metric tons of vanilla beans, about 80 percent of world production (Rasoanaivo et al. 1998).

The market price of vanilla rose dramatically in the late 1970s, due to a typhoon. Prices stayed stable at this level through the early 1980s despite the pressure of recently introduced Indonesian vanilla. In the mid-1980s, the cartel that had controlled vanilla prices and distribution since its creation in 1930 disbanded. Prices dropped 70 percent over the next few years, to nearly US$20 per kilo. This changed, due to typhoon Huddah, which struck early in the year 2000. The typhoon, political instability, and poor weather in the third year drove vanilla prices to an astonishing US$500 per kilo in 2004, bringing new countries into the vanilla industry. A good crop, coupled with decreased demand caused by the production of imitation vanilla, pushed the market price down to the $40 per kilo range in the middle of 2005.

Cultivation and production

| Country | Production (tonnes) |

% |

|---|---|---|

| 6,200 | 59% | |

| 2,399 | 23% | |

| 1,000 | 10% | |

| 306 | ||

| 192 | ||

| 144 | ||

| 195 | ||

| 65 | ||

| 50 | ||

| 23 | ||

| 20 | ||

| 10 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 8 | ||

| 3 | ||

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organization [1] | ||

Madagascar (mostly the fertile region of Sava) accounts for half of the global production of vanilla. Mexico, once the leading producer of natural vanilla with an annual 500 tons, produced only 10 tons of vanilla in 2006. An estimated 95% of “vanilla” products actually contain artificial vanillin, produced from lignin(RVCA).

The main species harvested for vanillin is Vanilla planifolia. Although it is native to Mexico, it is now widely grown throughout the tropics. Additional sources include Vanilla pompona and Vanilla tahitiensis (grown in Tahiti), although the vanillin content of these species is much less than Vanilla planifolia.

Vanilla grows as a vine, climbing up an existing tree, pole, or other support. It can be grown in a wood (on trees), in a plantation (on trees or poles), or in a "shader," in increasing orders of productivity. Left alone, it will grow as high as possible on the support, with few flowers. Every year, growers fold the higher parts of the plant downwards so that the plant stays at heights accessible by a standing human. This also greatly stimulates flowering.

The process for obtaining pure vanilla is very time consuming and labor intensive, involving hand pollination, about six weeks for the pods to reach full size, eight to nine months after that to mature, hand picking of the mature pods, and a three to six month process for curing (Herbst 2001). The curing process involves a boiling-water bath, sun heating, wrapping and allowing the beans to sweat, and so forth. Over months of drying in the sun during the day and sweating at night, they shrink by 400 percent and turn a characteristic dark brown (Herbst 2001). And to make it even more remarkable, the flower is open only one day a year, and perhaps for a few hours (Herbst 2001). The following is more detail on this process.

The distinctively flavored compounds are found in the fruit, which results from the pollination of the flower. One flower produces one fruit. There is only one natural pollinator, the Melipona bee, which is found in Mexico (Herbst 2001). Growers have tried to bring this bee into other growing locales, to no avail. The only way to produce fruits is thus artificial pollination. Hand pollinators can pollinate about 1,000 flowers per day.

The simple and efficient artificial pollination method introduced in 1841 by the 12-year-old slave named Edmond Albius on Réunion is still used today. Using a beveled sliver of bamboo, an agricultural worker folds back the membrane separating the anther and the stigma, then presses the anther on the stigma. The flower is then self-pollinated, and will produce a fruit. The vanilla flower lasts about one day, sometimes less, thus growers have to inspect their plantations every day for open flowers, a labor-intensive task.

The fruit (a seed capsule), if left on the plant, will ripen and open at the end; it will then release the distinctive vanilla smell. The fruit contains tiny, flavorless seeds. In dishes prepared with whole natural vanilla, these seeds are recognizable as black specks.

Like other orchids' seeds, vanilla seed will not germinate without the presence of certain mycorrhizal fungi. Instead, growers reproduce the plant by cutting: they remove sections of the vine with six or more leaf nodes, a root opposite each leaf. The two lower leaves are removed, and this area is buried in loose soil at the base of a support. The remaining upper roots will cling to the support, and often grow down into the soil. Growth is rapid under good conditions.

The basic production method is as follows:

- Harvest

- The pods are harvested while green and immature. At this stage, they are odorless.

- Killing

- The vegetative tissue of the vanilla pod is killed to prevent further growing. The method of killing varies, but may be accomplished by sun killing, oven killing, hot water killing, killing by scratching, or killing by freezing.

- Sweating

- The pods are held for 7 to 10 days under hot (45º-65°C or 115º-150°F) and humid conditions; pods are often placed into fabric covered boxes immediately after boiling. This allows enzymes to process the compounds in the pods into vanillin and other compounds important to the final vanilla flavor.

- Drying

- To prevent rotting and to lock the aroma in the pods, the pods are dried. Often, pods are laid out in the sun during the mornings and returned to their boxes in the afternoons. When 25-30% of the pods' weight is moisture (as opposed to the 60-70% they began drying with) they have completed the curing process and will exhibit their fullest aromatic qualities.

- Grading

- Once fully cured, the vanilla is sorted by quality and graded.

There are three main commercial preparations of natural vanilla:

- whole pod

- powder (ground pods, kept pure or blended with sugar, starch or other ingredients) (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 12.5% of pure vanilla (ground pods or oleoresin) in the mixture (FDA 1993).)

- extract (in alcoholic solution). (The U.S. Food and Drug Administration requires at least 35% vol. of alcohol and 13.35 ounces of pod per gallon (FDA 2007).)

Specific types of vanilla

Bourbon vanilla or Bourbon-Madagascar vanilla, produced from Vanilla planifolia plants introduced from the Americas, is the term used for vanilla from Indian Ocean islands such as Madagascar, the Comoros, and Réunion, formerly the Île Bourbon.

Mexican vanilla, made from the native Vanilla planifolia, is produced in much less quantity and marketed as the vanilla from the land of its origin. Vanilla sold in tourist markets around Mexico is sometimes not actual vanilla extract, but is mixed with an extract of the tonka bean, which contains coumarin. Tonka bean extract smells and tastes like vanilla, but coumarin has been shown to cause liver damage in lab animals and is banned in the US by the Food and Drug Administration.[1]

Tahitian vanilla is the name for vanilla from French Polynesia, made with Vanilla tahitiensis. This species is descended from V. plantifolia that was introduced to Tahiti before mutating into a distinct species.[2][dubious — see talk page]

The term French vanilla is not a type of vanilla, but is often used to designate preparations that have a strong vanilla aroma, and contain vanilla grains. The name originates from the French style of making ice cream custard base with vanilla pods, cream, and egg yolks. Alternatively, French vanilla is taken to refer to a vanilla-custard flavour.[3] Syrup labelled as French vanilla may include custard, caramel or butterscotch flavours in addition to vanilla.

Culinary uses

Vanilla flavouring in food may be achieved by adding vanilla extract or by cooking vanilla pods in the liquid preparation. A stronger aroma may be attained if the pods are split in two, exposing more of the pod's surface area to the liquid. In this case, the pods' seeds are mixed into the preparation. Natural vanilla gives a brown or yellow colour to preparations, depending on the concentration.

Good quality vanilla has a strong aromatic flavour, but food with small amounts of low quality vanilla or artificial vanilla-like flavourings are far more common, since true vanilla is much more expensive.

A major use of vanilla is in flavouring ice cream. The most common flavour of ice cream is vanilla, and thus most people consider it to be the "default" flavour. By analogy, the term "vanilla" is sometimes used as a synonym for "plain."

The cosmetics industry uses vanilla to make perfume.

The food industry uses methyl and ethyl vanillin. Ethyl vanillin is more expensive, but has a stronger note. Cook's Illustrated ran several taste tests pitting vanilla against vanillin in baked goods and other applications, and to the consternation of the magazine editors, tasters could not differentiate the flavour of vanillin from vanilla;[4] however, for the case of vanilla ice cream, natural vanilla won out.[5]

Medicinal effects

In old medicinal literature, vanilla is described as an aphrodisiac and a remedy for fevers. These purported uses have never been scientifically proven, but it has been shown that vanilla does increase levels of catecholamines (including epinephrine, more commonly known as adrenaline), and as such can also be considered mildly addictive.[6][7]

In an in-vitro test vanilla was able to block quorum sensing in bacteria. This is medically interesting because in many bacteria quorum sensing signals function as a switch for virulence. The microbes only become virulent when the signals indicate that they have the numbers to resist the host immune system response.[8]

The essential oils of vanilla and vanillin are sometimes used in aromatherapy.

- Vanilla planifolia 1.jpg

Flower

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bender, D. A., and A. E. Bender. 2005. A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198609612.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 1993. Part 169: Food dressings and flavorings. Subpart A—General provisions. Subpart B—Requirements for specific standardized food dressings and flavorings. Sec. 169.179. Vanilla powder.. 21CFR169.179. Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 2007. Part 169: Food dressings and flavorings. Subpart A&mdsh;General provisions. Sec. 169.3 Definitions. 21CFR169.3. Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

- Havkin-Frenkel, D., J. C. French, N. M. Graft, F. E. Pak, C. Frenkel, and D. M. Joel. 2004. [Cite error: Closing

</ref>missing for<ref>tag

- Herbst, S. T. 2001. The New Food Lover's Companion: Comprehensive Definitions of Nearly 6,000 Food, Drink, and Culinary Terms. Barron's Cooking Guide. Hauppauge, NY: Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 0764112589.

- Rainforest Vanilla Conservation Association. n.d. Global warming and artificial vanillin. Rainforest Vanilla Conservation Association. Retrieved April 11, 2008.

External links

- Electronic Plant Information Centre at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 2003-11-8

- Spices at UCLA History & Special Collections

- Spice Pages—Vanilla

- Did you know?

- Mexican Gourmet Vanilla: History

- Vanilla and Extracts at the Open Directory Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ IMPORT ALERT IA2807: "DETENTION WITHOUT PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF COUMARIN IN VANILLA PRODUCTS (EXTRACTS - FLAVORINGS - IMITATIONS)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration Office of Regulatory Affairs (30). Retrieved 2007-12-21.

- ↑ www.vanilla.com FAQ.

- ↑ www.vanilla.com FAQ.

- ↑ Vanilla Essence VS Imitation Vanilla Essence - Discuss Cooking Forum

- ↑ Tasting lab : The Scoop on Vanilla Ice Cream

- ↑ http://www.organicmd.org/faq.html[2]

- ↑ http://wwwwww.nwcr.ws/adam/healthillustratedencyclopedia/1/003561.html[3]

- ↑ [[Choo JH, Rukayadi Y, Hwang JK.|]] (2006 Jun) Inhibition of bacterial quorum sensing by vanilla extract.. Lett Appl Microbiol. 42 (6): 637-41. PMID: 16706905.

- ↑ "Vanilla Miller" by James D. Ackerman, Flora of North America 26:507, June 2003.

- ↑ Correll D (1953) Vanilla: its botany, history, cultivation and economic importance. Econ Bo 7(4): 291–358.

- ↑ Rasoanaivo P et al (1998) Essential oils of economic value in Madagascar: Present state of knowledge. HerbalGram 43:31–39,58–59.