Difference between revisions of "Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park" - New World Encyclopedia

Mary Anglin (talk | contribs) (→Flora) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (82 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Images OK}} | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{copyedited}} |

{{Infobox World Heritage Site | {{Infobox World Heritage Site | ||

| WHS = Ulu<u>r</u>u-Kata Tju<u>t</u>a National Park | | WHS = Ulu<u>r</u>u-Kata Tju<u>t</u>a National Park | ||

| − | | Image = [[Image: | + | | Image = [[Image:Uluru_sunset1141.jpg|300px|Uluru at Sunset]] |

| State Party = {{AUS}} | | State Party = {{AUS}} | ||

| Type = Mixed | | Type = Mixed | ||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/447 | | Link = http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/447 | ||

}} | }} | ||

| − | + | The '''Ulu<u>r</u>u-Kata Tju<u>t</u>a National Park''' lies in [[Australia]]'s [[Northern Territory]], east of the [[Petermann Ranges]] and the Petermann Aboriginal Land Trust’s territory. It was first established in 1958, as the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park. In 1993, the official name of the Park was changed to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. | |

| − | '''Ulu<u>r</u>u-Kata Tju<u>t</u>a''' | + | |

| + | The Park is majestic and serene and covers 1,326 square kilometers (512 sq mi). It is named for its two most prominent features—the Uluru and, 40 km (25 mi) to its west, Kata Tjuta rock formations (in [[English language|English]], "Ayers Rock" and "The Olgas," respectively). Both rock outcroppings are considered [[sacred]] sites and thus important spiritually and ceremonially to the [[Anangu]]. The region is rich in indigenous [[culture]] with many [[rock cave]]s and ancient paintings alongside natural springs and rock pools in a [[desert]] landscape. The park was designated a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]] in 1987, extended 1994, in recognition of its value and cultural and natural significance. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The importance of the site to the Australia's original inhabitants prompted government action to acknowledge them as the territory's traditional owners. A joint management plan between the government and the aboriginal people was established in 1985. The Anangu people, recognized as traditional owners and chief custodians of the park, have a complex system of belief known as [[Tjukurpa]] (pronounced "chu-ka-pa"). Tjukurpa encompasses [[religion]], [[law]] and the relationship between [[human being|people]], [[animal]]s, [[plant]]s, and the landscape. The management of the park is carried out according to Tjukurpa. | ||

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Ulurumap.png|thumb|275px|Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park's location in Australia.]] |

| − | [[ | + | The Uluru (Ayers Rock) is an [[inselberg]] (an isolated hill or lone mountain that has risen above the surrounding area, typically by surviving erosion) composed of arkosic [[sandstone]]. Uluru is oval in shape, 3.6 kilometer (2.2 mi) long by 2 kilometer (1.5 mi) wide. Its top is scored with gullies and basins that produce giant cataracts after infrequent rainstorms. The [[erosion]] of weaker rock layers have fluted the lower slopes. There are shallow [[cave]]s at the rock's base which contain ancient carvings and paintings and are sacred to the Aboriginal peoples. It is one of the Northern Territory's most recognizable natural icons. |

| − | + | ||

| + | Kata Tjuta (The Olgas), meaning "many heads," is a circular grouping of 36 red conglomerate domes rising above the desert plains, covering an area of 28 sq km (11 sq mi). The largest is Mount Olga which is 460 meters (1,500 feet) above the plain and 1069 meters (3,507 ft) above sea level. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Both rocks offer a constantly changing array of color, as the sandstone seems to change color according to the sun's position. At sunset they become a fiery orange-red. The deep clefts between the domes of Kata Tjuta hold lush vegetation which is accentuated by the moving sun. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Cultural significance=== | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru_2.JPG|thumb|Ancient cave painting in Uluru.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru petrogpyph.jpg|thumb|Petroglyphs in Uluru.]] | ||

[[Anangu]] are the traditional [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal]] owners of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. They believe their culture was created at the beginning of time by ancestral beings and has always existed in the Central Australian landscape. According to traditional lore, [[Uluru]] and Kata Tjuta provide physical evidence of feats performed during the creation period. | [[Anangu]] are the traditional [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal]] owners of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. They believe their culture was created at the beginning of time by ancestral beings and has always existed in the Central Australian landscape. According to traditional lore, [[Uluru]] and Kata Tjuta provide physical evidence of feats performed during the creation period. | ||

| − | Both [[Uluru]] (also known as Ayers Rock) and [[Kata Tjuta]] (known as The Olgas) are considered sacred sites and thus important spiritually and cermonially to the Anangu. There are more than forty named sacred sites and eleven separate [[Tjurkurpa]] (or | + | Both [[Uluru]] (also known as Ayers Rock) and [[Kata Tjuta]] (known as The Olgas) are considered sacred sites and thus important spiritually and cermonially to the Anangu. There are more than forty named sacred sites and eleven separate [[Tjurkurpa]] (or "Dreaming") tracks in the area. Some of these dreaming tracks lead as far as the sea in all directions. |

The Anangu have resided mostly in the northwest area of the state of [[South Australia]], extending into the Northern Territory and a short distance into Western Australia. The land is an inseparable and important part of their identity, and every part of it is rich with stories and meaning to Anangu. | The Anangu have resided mostly in the northwest area of the state of [[South Australia]], extending into the Northern Territory and a short distance into Western Australia. The land is an inseparable and important part of their identity, and every part of it is rich with stories and meaning to Anangu. | ||

| − | While political borders have generally held little meaning for indigenous peoples, the border separating the Northern Territory and South Australia served as an impediment to the Anangu in their claim to the sacred lands. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act was passed in 1976, meaning that after many years Aboriginal law and land rights were finally recognized in [[Australian law]]. In 1979 the [[Central Land Council]], which represents the indigenous people predominantly in land issues, laid claim to the area that | + | While political borders have generally held little meaning for indigenous peoples, the border separating the Northern Territory and South Australia served as an impediment to the Anangu in their claim to the sacred lands. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act was passed in 1976, meaning that after many years Aboriginal law and land rights were finally recognized in [[Australian law]]. In 1979, the [[Central Land Council]], which represents the indigenous people predominantly in land issues, laid claim to the area that was then known the "Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park." This claim was fiercely resisted by the [[Northern Territory]] government. |

| − | After eight years of intensive lobbying by the Traditional Owners, Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced that the Federal Government intended to transfer inalienable freehold title to them. He also agreed to ten main points they had demanded in exchange for a lease-back arrangement to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service for a "joint-management" system in which Anangu would have a majority on the Board of Management. This was finally granted in 1985, but with the government rejecting two of the most important points the Anangu had requested: | + | After eight years of intensive lobbying by the Traditional Owners, Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced that the Federal Government intended to transfer inalienable freehold title to them. He also agreed to ten main points they had demanded in exchange for a lease-back arrangement to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service for a "joint-management" system in which Anangu would have a majority on the Board of Management. This was finally granted in 1985, but with the government rejecting two of the most important points the Anangu had requested: They were forced to agree to lease the Park for 99 years, instead of the fifty years originally agreed on, perhaps more importantly, they had to allow tourists to climb Uluru, which they believed was an act of desecration of one of their main dreaming tracks. Park Management has erected signs asking visitors not to climb the "Rock," but have no authority to enforce it, and many thousands of visitors are said to climb the rock every year, assisted by a chain handhold added in 1964 and extended in 1976. |

In spite of the disagreements, since hand-back, Anangu and Parks Australia staff have worked together to manage the Park. Management policy and programs seek to maintain [[Anangu]] [[culture]] and heritage, conserve and protect the integrity of the [[ecology|ecological]] systems in and around the Park while providing for visitor enjoyment and educational opportunities within the Park. | In spite of the disagreements, since hand-back, Anangu and Parks Australia staff have worked together to manage the Park. Management policy and programs seek to maintain [[Anangu]] [[culture]] and heritage, conserve and protect the integrity of the [[ecology|ecological]] systems in and around the Park while providing for visitor enjoyment and educational opportunities within the Park. | ||

===Park establishment=== | ===Park establishment=== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:ApproachToKataJuta_edit1.jpg|thumb|300px|The approach to Kata Tjuta]] |

| − | [[ | + | Established as a [[national park]] in 1958 with the name "Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park," it has benefited under the joint-management which began in 1985. In 1987, it was listed as a [[UNESCO]] [[World Heritage Site]] for the [[conservation]] of [[natural environment|nature]]. In 1993, the official name of the Park changed to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. In 1994, UNESCO extended its designation to recognize the park's [[culture|cultural significance]]. |

| − | In 1987, | ||

| − | In 1995 Parks Australia and the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management won the Picasso Gold Medal, the highest UNESCO award for outstanding preservation efforts of the park. They were noted for setting new international standards for World Heritage management. | + | In 1995, Parks Australia and the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management won the Picasso Gold Medal, the highest UNESCO award for outstanding preservation efforts of the park. They were noted for setting new international standards for World Heritage management. |

| − | The National Parks and [[Wildlife Conservation Act]] 1975 was replaced in July 2000 by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The declaration of the Park was continued under the new Act. | + | The National Parks and [[Wildlife Conservation Act]] 1975 was replaced in July 2000, by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The declaration of the Park was continued under the new Act. |

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Uluru sunset1133.jpg|thumb|225px||Uluru at sunset]] |

| − | + | In separate expeditions, [[William Ernest Powell Giles]] and [[William Christie Gosse]] were the first European explorers to this area. In 1872, while exploring the area, Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from near [[Kings Canyon]] and called it [[Mount Olga]], while the following year Gosse saw Uluru and named it [[Ayers Rock]] after Sir Henry Ayers, the Chief Secretary of [[South Australia]]. Both Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the [[Overland Telegraph |Overland Telegraph Line]] in 1872. Further explorations followed with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for [[pastoralism]]. | |

| − | Uluru | ||

| − | |||

| − | In separate expeditions, [[William Ernest Powell Giles]] and [[William Christie Gosse]] were the first European explorers to this area. In 1872 while exploring the area, Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from near [[Kings Canyon]] and called it [[Mount Olga]], while the following year Gosse saw Uluru and named it [[Ayers Rock]] after Sir Henry Ayers, the Chief Secretary of [[South Australia]]. Further explorations followed with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | In the late 1800s, interaction between [[Anangu]] and white people became more frequent as pastoralists attempted to establish themselves in the area. Due to the effects of grazing and droughts, bush food stores were depleted. Competition for these resources created conflict between the new settlers and the indigenous population. Their interactions were often violent and police patrols became more frequent. |

| − | + | Between 1918 and 1921, large adjoining areas of [[South Australia]], [[Western Australia]] and the [[Northern Territory]] were declared as [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal reserves]]. In 1920, part of the area that was to become Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was declared an Aboriginal Reserve (commonly known as the South-Western or Petermann Reserve) by the Australian Government under the Aboriginals Ordinance (NT). | |

| − | + | During the [[Great Depression]] of the 1930s, Anangu became involved in dingo scalping with "doggers" who introduced Anangu to European foods and ways. The first tourists visited the Uluru area in 1936. By 1959, the first motel leases had been granted and an airstrip was built near the northern side of Uluru. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Geography and geology== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Uluru1_2003-11-21.jpg|thumb| Aerial view of Uluru.]] | |

| + | [[Image:Uluruinthedesert.JPG|thumb|Desert landscape surrounding Uluru.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru Wildflowers.jpg|thumb|Wildflowers in bloom with Kata Tjuta in the background.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Desert_Oaks3484.jpg|thumb|Desert Oaks with Kata Tjuta in the background.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Spinifex_grass.jpg|thumb|Spinifex grass.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Alice_Springs4260.jpg|thumb|Bush tucker (bushfood).]] | ||

| + | From a [[geology|geological]] point of view, analysis of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park reveals an awe-inspiring history. Five hundred million years ago, the entire area was covered by an [[inland sea]] and over many centuries, sand and mud fell to the bottom of the sea, creating rock and [[sandstone]]. Kata Tjuta's domes are the eroded remains of sedimentary rock from the seabed, while Uluru is a relic of the coarse grained, mineral-rich sandstone called [[arkose]]. | ||

| − | + | ===Climate and seasons=== | |

| − | + | The park receives an average rainfall of 308 millimeters (12 inches) per year. [[Temperature]] extremes in the park have been recorded at 45°C (113°F) during the summer and -5°C (23°F) during winter nights. | |

| − | + | While the Central Australian environment may at first seem stark—a barren landscape supporting spectacular rock formations—closer inspection reveals it as a complex [[ecosystem]], full of life. | |

| − | + | [[Plant]] and [[animal]] life have adapted to the area's extreme conditions and it subsequently supports some of the most unusual flora and fauna on the planet. Many of these have long been a valuable source of [[bush tucker]] and [[medicine]] for local [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal]] people, who recognize six [[season|seasons]]: | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | # Piryakatu (August/September)—Animals breed and food plants flower | |

| + | # Wiyaringkupai (October/November)—The really hot season when food becomes scarce | ||

| + | # Itanju (January/February)—Sporadic storms can roll in suddenly | ||

| + | # Wanitjunkupai (March)—Cooler weather | ||

| + | # Tjuntalpa (April/May)—Clouds roll in from the south | ||

| + | # Wari (June/July)—Cold season bringing morning frosts | ||

| − | + | The Park is ranked as one of the most significant arid land ecosystems in the world. As a [[Biosphere Reserve]] under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Program, it joins an international network aiming to preserve the world's major [[ecosystem]] types. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Flora=== | |

| + | Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park [[flora]] represents a large portion of [[plant]]s found in [[Central Australia]]. There are several rare and [[endangered species]] in the Park. Most of them are restricted to the moist areas at the base of the inselbergs, which are areas of high visitor use and subject to erosion. | ||

| − | + | The [[desert]] flora has adapted to the harsh conditions. The growth and reproduction of plant communities rely on irregular [[rain]]fall. Some plants are able to survive [[fire]] and some are dependent on it to reproduce. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Plants are an important part of the indigenous spiritual traditions, many of which are associated with [[ancestral]] beings. There are special ceremonies for each of the major plant foods. Collection of plant foods remains a culturally important activity, reinforcing traditional links with country and ''Tjukurpa''. [[Indigenous Australians|Native]] specifications for the local flora include: | |

| + | * "Punu"—trees | ||

| + | * "Puti"—shrubs | ||

| + | * "Tjulpun-tjulpunpa"—flowers | ||

| + | * "Ukiri"—grasses | ||

| − | + | [[Tree]]s such as the [[mulga]] and centralian [[bloodwood]] are used to make tools such as spearheads, [[boomerang]]s and bowls. The red [[sap]] of the bloodwood is used as a [[disinfectant]] and an inhalant for [[cough]]s and [[Common cold|colds]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Others, such as the [[Eucalyptus|river red gum]] and [[Duboisia |corkwood trees]] like [[grevillea]] and hakeas, are a source of food themselves. The white flaky crust from river red gum leaves can be rolled into balls and eaten like [[candy]], while the [[nectar]] from the [[flower]]s of the corkwood trees produce a sweet drink. |

| − | |||

| − | Others such as the [[ | + | [[Daisy|Daisies]] and other ground flowers bloom after [[rain]] and during the [[winter]]. Others such as the wattles bloom as spring approaches. [[Anangu]] collect wattle seed, crush and mix it with water to make an edible paste which they eat raw. To make [[damper]], the seeds are parched with hot [[sand]] so their skins can be removed before they are ground for flour. |

| − | + | The prickly hard [[spinifex]] hummocks have enormous [[root system]]s that prevent desert sand shifting. The hummock roots spread underground beyond the prickly clump and deeply into the [[soil]] forming an immense cone. Anangu use a resin gathered from the gummy spinifex to make [[Spinifex resin|gum]]. They thresh the spinifex until the resin particles fall free. These particles are heated until they fuse together to form a moldable black tar which is worked while warm. The gum is used for hunting and working implements, and to mend breaks in stone and wooden implements. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The prickly hard [[spinifex]] hummocks have enormous root | ||

| − | The naked woolybutt and native [[millet]] have seeds that are important Anangu foods. Women rub the [[seed]] heads from their stalks and then separate the seeds from the chaff by | + | The naked woolybutt and native [[millet]] have seeds that are important Anangu foods. Women rub the [[seed]] heads from their stalks and then separate the seeds from the chaff by skillful winnowing. Using grinding stones, they then grind the seeds to flour for damper. |

| − | + | Since the European arrival in the area, 34 introduced plant species have been recorded in the Park, representing about 6.4 percent of the total park flora. Some, such as perennial buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), were intentionally introduced to rehabilitate areas damaged by [[erosion]]. It is the most threatening weed in the Park and has spread to invade water and nutrient rich drainage lines. Where infestation is dense, it prevents the growth of native grasses. A few others such as burrgrass were brought in accidentally, carried on cars and people. | |

| − | + | ===Fauna=== | |

| + | [[Image:Brushtail_possum.jpg|thumb|200px|Brushtail possum]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Perentie_Lizard_Perth_Zoo_SMC_Spet_2005.jpg|200px|thumb|Perentie Lizard]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Black-footed_Rock-wallaby(small).jpg|upright|200px|thumb|Black-footed Rock-wallaby]] | ||

| + | Historically, 46 [[species]] of native [[mammal]] are known to have lived in the Uluru region; currently 21 species remain, reflecting negative implications for the condition and health of the landscape. Moves are supported for the reintroduction of locally extinct [[animal]]s such as [[Mallee_Fowl| mallee fowl]], [[Brushtailed_possum| brushtail possum]], rufous hare [[wallaby]], or [[Rufous_Hare_Wallaby| mala]], [[bilby]], [[Burrowing_Bettong| burrowing bettong]], and the [[Black-footed_Rock-Wallaby |black footed rock wallaby]]. | ||

| − | + | The [[mulgara]], the only mammal listed as vulnerable, is mostly restricted to the transitional sandplain area, a narrow band of country that stretches from the vicinity of Uluru, to the Northern boundary of the Park, and into Ayers Rock Resort. This area also contains [[marsupial mole]], [[Woma_Python| woma python]], or kuniya, and great desert skink. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | The [[ | + | The [[bat]] population of the Park comprises at least seven [[species]] that depend on day roosting sites within [[cave]]s and crevices of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Most of the bats forage for aerial [[prey]] within an airspace extending only 100 m (328 ft) or so from the rock face. |

| − | [[ | + | The Park has a very rich [[reptile]] fauna of high conservation significance with 73 species having been reliably recorded. Four species of [[frog]] are abundant at the bases of Uluru and Kata Tjuta following summer rains. The great desert [[skink]] is listed as [[Vulnerable species|vulnerable]]. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | [[Anangu]] continue to hunt and gather animal species in remote areas of the Park and on Anangu land elsewhere. Hunting is largely confined to the [[red kangaroo]], Australian [[bustard]], [[emu]], and [[lizard]]s such as the sand [[goanna]] and [[perentie]]. | |

| − | The | + | ====Introduced species==== |

| + | The pressures exerted by introduced predators and herbivores on the original mammalian fauna of Central Australia were a major factor in the extinction of about 40 percent of the native species. | ||

| − | [[ | + | Of the 27 [[mammal]] species found in the Park, six are introduced: The [[house mouse]]; [[camel]]; [[fox]]; [[cat]]; [[dog]]; and [[rabbit]]. These species are distributed throughout the Park but their densities are greatest in the rich water run off areas of [[Uluru]] and [[Kata Tjuta]]. |

| − | + | Large numbers of [[rabbit]]s led to the introduction of a rabbit control program in 1989. This has resulted in a great reduction of the rabbit population, a noticeable vegetation recovery, and a reduction in [[predator]] numbers. | |

| − | + | [[Camel]]s have been implicated in the reduction of plant species, particularly the more succulent species such as the [[quandong]]. The [[house mouse]] is a successful invader of disturbed environments and habitats that have lost native rodents. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Subjective estimates of [[cat]] and [[fox]] numbers have been collected in association with the rabbit control program. The national threat abatement programs may provide the framework for controlling them. Anangu knowledge and tracking skills are invaluable in the management of these introduced animals. The Park regulations prohibit visitors bringing animals into the Park unless they are a [[guide dog]] for the blind or deaf, or a permit is granted by the Director of National Parks. | Subjective estimates of [[cat]] and [[fox]] numbers have been collected in association with the rabbit control program. The national threat abatement programs may provide the framework for controlling them. Anangu knowledge and tracking skills are invaluable in the management of these introduced animals. The Park regulations prohibit visitors bringing animals into the Park unless they are a [[guide dog]] for the blind or deaf, or a permit is granted by the Director of National Parks. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Fire management== |

| − | [[ | + | [[Fire]]s have been a part of central [[desert]] land management for thousands of years and have shaped the landscape, habitats, survival of [[animal]]s, and patterns of [[vegetation]]. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Controlled burning usually takes place during the [[winter]] months because of the cooler [[weather]], while natural fires mostly occur in the early [[summer]] months. Natural fires are usually started by the [[lightning]] strikes of dry electrical storms from the northwest. When the storms arrive the weather is usually hot, dry and windy—conditions ideal for raging fires. Damage can be severe and widespread. | |

| − | + | Traditional burning of the Uluru area ended when [[Anangu]] were driven from the region during the 1930s. During the 1940s [[rain]]fall was good and vegetation flourished. A fire in 1950, fed by the natural fuel grown during the previous 20 years, destroyed approximately one third of the Park's vegetation. The pattern repeated itself and in 1976, two fires burned over three-quarters of the Park. Destructive bushfires burned much of the Park, and nearby luxury accommodations at the Ayers Rock Resort were destroyed in the 2002-2003 season. | |

| − | + | The value of traditional burning has come to be understood and today most fires in the park are lit according to land management patterns traditionally practiced by the [[Indigenous Australian|Indigenous people]]. Traditional fire and land management skills enable controlled burns that will give the desired result. These skills are vital for the preservation of the central Australian [[ecology]]. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | == | + | ==Tourism and facilities== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:Mala_Walk1178.jpg|thumb|Mala Walk Uluru]] | [[Image:Mala_Walk1178.jpg|thumb|Mala Walk Uluru]] | ||

| − | |||

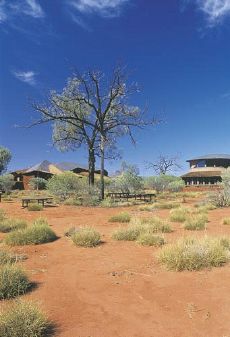

| − | + | The development of [[tourism]] infrastructure adjacent to the base of Uluru that began in the 1950s soon produced adverse [[natural environment|environmental]] impacts. It was decided in the early 1970s to remove all [[accommodation]] related tourist facilities and re-establish them outside the Park. | |

| − | + | In 1975, a reservation of 104 square kilometers (40 sq mi) of land beyond the park's northern boundary, 15 kilometers (8 mi) from [[Uluru]], was approved for the development of a tourist facility and an associated airport, to be known as Yulara. The campground within the Park was closed in 1983 and the motels closed in late 1984, coinciding with the opening of the Yulara resort. In 1992, the majority interest in the Yulara Resort held by the Northern Territory Government was sold and the resort was renamed "Ayers Rock Resort." | |

| − | + | Since the Park's designation as a [[World Heritage Site]], annual visitor numbers have risen to nearly a half-million. Increased [[tourism]] provides regional and national economic benefits, as well as presents an ongoing challenge to balance [[conservation]] of [[culture|cultural]] values and visitor needs. | |

| − | + | There are a number of walking trails that visitors can take around the major attractions of the Park. The Base Walk is one of the best ways to see [[Uluru]]. Other walks surrounding Uluru include the Liru Walk, Mala Walk and Kuniya walk, while the [[sunrise]] and [[sunset]] viewing areas provide for a great visual experience. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Cultural traditions=== | |

| + | [[Image:Australie_3_034.jpg|upright|thumb|Though the [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal peoples]], traditional owners of the land, consider climbing Uluru to be sacred desecration, a walking trail with an assistance chain has been installed on Uluru.]] | ||

| + | The Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Cultural Centre, located inside the Park on the main road to [[Uluru]], provides an introduction to Tjukurpa, Anangu art, Anangu way of life (traditional and current), [[history]], [[language]]s, [[wildlife]], and joint management of the Park. There are also [[Aboriginal_art| art]] and [[craft]] demonstrations, [[bush tucker]] sessions, plants walks and cultural presentations. | ||

| − | + | There are displays featuring photo collages, oral history sound panels, Pitjantjatjara [[language]] learning interactives, soundscapes, videos and artifacts. Explanations are provided in Pitjantjatjara, [[English language|English]], [[Italian language|Italian]], [[Japanese language|Japanese]], [[German language|German]], and [[French language|French]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Uluru climb is the traditional route taken by ancestral [[Mala]] men upon their arrival in the area. Anangu do not climb Uluru because of the spiritual significance it holds for them, and have requested that visitors be educated, and thus choose to respect their law and [[culture]] by not climbing. The Cultural Centre in the Park provides such cultural information to visitors. | |

| − | + | The Valley of the Winds walk is an alternative to climbing Uluru, and offers views of the spectacular landscape from two lookout points along the track. The walk is steep, rocky and difficult in places. For safety reasons this walk is closed under certain circumstances including heat, darkness and during rescue efforts. | |

| − | [[ | + | The [[Indigenous Australian|Aboriginal community]] of Mutitjulu is inside the park area, but there are no provisions for tourists, who must stay at the resorts in the township of Yulara. The [[national park]] and town are served by [[Ayers Rock Airport|Connellan Airport]]. |

| − | + | ==Park management== | |

| + | Upon the agreement to form a joint-management system in 1985, with Anangu forming the majority of the Board of Management, then Governor General Sir [[Ninian Stephen]] presented the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park title deeds back to Anangu. This act served to both acknowledge and respect their position as the land's traditional owners. | ||

| + | The Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management was established under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act (1975) on December 10, 1985, and held its first meeting on April 22, 1986. The Board of Management continues under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999. | ||

| + | [[Image:Cultural_Centre_Uluru1155.jpg|upright|thumb|Cultural Centre Uluru]] | ||

The lease agreement ensures that the Director of National Parks: | The lease agreement ensures that the Director of National Parks: | ||

| − | * | + | * Has an Anangu majority on the Board of Management |

| − | * | + | * Encourages the maintenance of Anangu tradition through protection of sacred sites and other areas of significance |

| − | * | + | * Maximizes Anangu involvement in Park administration and management, and provides necessary training |

| − | * | + | * Delivers training programs to Anangu to enable them to take up employment in the Park |

| − | * | + | * Maximizes Anangu employment in the Park by accommodating Anangu needs and cultural obligations with flexible working conditions |

| − | * | + | * Uses Anangu traditional skills in Park management |

| − | * | + | * Actively supports the delivery of cross-cultural training by Anangu to Park staff, local residents and Park visitors |

| − | * | + | * Consults regularly with Anangu |

| − | * | + | * Encourages Anangu commercial activities in the Park |

| − | * | + | * Makes rental payments to the members of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta lands trust |

| − | * | + | * Maintains the Park to best practice standards |

| − | * | + | * Involves Anangu in staff selection |

Of the 12 members of the Board of Management: | Of the 12 members of the Board of Management: | ||

| Line 208: | Line 192: | ||

* One member is the Director of National Parks. | * One member is the Director of National Parks. | ||

| − | Board members | + | Board members normally sit for a term of five years before a new nomination process takes place. All nominees are appointed by the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources after a consultation process. Board meetings are held at least four times a year with all matters discussed in both English and Pitjantjatjara and/or Yankunytjatjara. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Image:Uluru_Panorama.jpg|center|thumb| | + | Tjukurpa (Aboriginal wisdom of life-harmony) guides the development and interpretation of Park policy as set out in the Plan of Management. Plans of Management are developed in consultation with Anangu and a wide range of individuals and organizations associated with the Park. |

| + | <center> | ||

| + | {| | ||

| + | |+ | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[Image:Australie_2_389.jpg|190px|thumb|Uluru at Sunrise]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru 1.JPG|190px|thumb|Uluru in mid-day]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[Image:Australien_21.jpg|thumb|190px|Rainbow above Uluru]] | ||

| + | | valign="top"| | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru Australia(1).jpg|190px|thumb|Uluru in the evening]] | ||

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | [[Image:Uluru_Panorama.jpg|center|thumb|550px|Panoramic view of sunset at Uluru.]] | ||

| − | + | <center> | |

| − | + | {| | |

| − | + | |+ | |

| − | [[Image: | + | |- |

| − | [[Image: | + | | valign="top"| |

| − | + | [[Image:Kata_Tjuta_1.JPG|200px|thumb|Kata Tjuta]] | |

| − | + | | valign="top"| | |

| − | + | [[Image:Kata_Tjuta_Australia.jpg|200px|thumb|Kata Tjuta]] | |

| − | + | | valign="top"| | |

| − | + | [[Image:Kata_Tjuta_2.jpg|200px|thumb|Kata Tjuta up close]] | |

| + | |- | ||

| + | |} | ||

| + | </center> | ||

| + | [[Image:MC_Olgas_pano.jpg|550px|center|thumb|A panorama of Kata Tjuta as seen from its viewing platform in the middle of the day.]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Hill, Barry. 1994. ''The Rock: Traveling to Uluru''. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781863737128. | ||

| + | * James, Sarah. 2005. ''Negotiating the Climb: Uluru, a Site of Struggle or a Shared Space?'' Melbourne: School of Anthropology, Geography and Environmental Studies, The University of Melbourne. ISBN 9780734030849. | ||

| + | * Kerle, Anne. 1995. ''Uluru, Kata Tjuta & Watarrka = Ayers Rock, the Olgas & Kings Canyon, Northern Territory''. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868400556. | ||

| + | * Roff, Derek. 1976. ''Mammals of the Ayers Rock-Mt. Olga National Park.'' Alice Springs, N.T.: Northern Territory Reserves Board. | ||

| + | * ''Tourism NT''. [http://www.tourismnt.com.au/ ''This site has provided some of the images contained in this article.''] Retrieved September 12, 2008. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | * [http://environment.gov.au/ | + | All links retrieved May 2, 2023. |

| − | + | * [http://www.environment.gov.au/parks/uluru/ Australian government info site] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{World Heritage Sites In Australia}} | {{World Heritage Sites In Australia}} | ||

[[Category:World Heritage Sites]] | [[Category:World Heritage Sites]] | ||

| − | [[Category:National | + | [[Category:National Parks]] |

[[Category:Australia]] | [[Category:Australia]] | ||

[[Category:Geography]] | [[Category:Geography]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Oceania]] | ||

{{credit|Uluru-Kata_Tjuta_National_Park|229520545|Kata_Tjuta|230232974|Pitjantjatjara|200777685}} | {{credit|Uluru-Kata_Tjuta_National_Park|229520545|Kata_Tjuta|230232974|Pitjantjatjara|200777685}} | ||

Latest revision as of 01:31, 3 May 2023

| Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

| |

| State Party | |

| Type | Mixed |

| Criteria | v, vi, vii, ix |

| Reference | 447 |

| Region** | Asia-Pacific |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

| Extensions | 1994 |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. | |

The Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park lies in Australia's Northern Territory, east of the Petermann Ranges and the Petermann Aboriginal Land Trust’s territory. It was first established in 1958, as the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park. In 1993, the official name of the Park was changed to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park.

The Park is majestic and serene and covers 1,326 square kilometers (512 sq mi). It is named for its two most prominent features—the Uluru and, 40 km (25 mi) to its west, Kata Tjuta rock formations (in English, "Ayers Rock" and "The Olgas," respectively). Both rock outcroppings are considered sacred sites and thus important spiritually and ceremonially to the Anangu. The region is rich in indigenous culture with many rock caves and ancient paintings alongside natural springs and rock pools in a desert landscape. The park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, extended 1994, in recognition of its value and cultural and natural significance.

The importance of the site to the Australia's original inhabitants prompted government action to acknowledge them as the territory's traditional owners. A joint management plan between the government and the aboriginal people was established in 1985. The Anangu people, recognized as traditional owners and chief custodians of the park, have a complex system of belief known as Tjukurpa (pronounced "chu-ka-pa"). Tjukurpa encompasses religion, law and the relationship between people, animals, plants, and the landscape. The management of the park is carried out according to Tjukurpa.

Description

The Uluru (Ayers Rock) is an inselberg (an isolated hill or lone mountain that has risen above the surrounding area, typically by surviving erosion) composed of arkosic sandstone. Uluru is oval in shape, 3.6 kilometer (2.2 mi) long by 2 kilometer (1.5 mi) wide. Its top is scored with gullies and basins that produce giant cataracts after infrequent rainstorms. The erosion of weaker rock layers have fluted the lower slopes. There are shallow caves at the rock's base which contain ancient carvings and paintings and are sacred to the Aboriginal peoples. It is one of the Northern Territory's most recognizable natural icons.

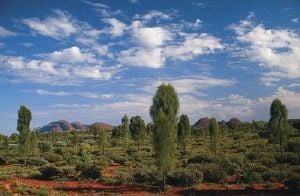

Kata Tjuta (The Olgas), meaning "many heads," is a circular grouping of 36 red conglomerate domes rising above the desert plains, covering an area of 28 sq km (11 sq mi). The largest is Mount Olga which is 460 meters (1,500 feet) above the plain and 1069 meters (3,507 ft) above sea level.

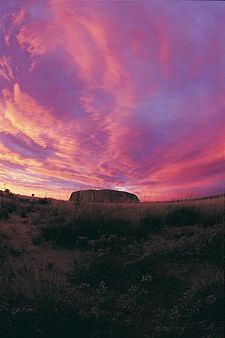

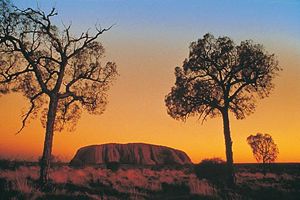

Both rocks offer a constantly changing array of color, as the sandstone seems to change color according to the sun's position. At sunset they become a fiery orange-red. The deep clefts between the domes of Kata Tjuta hold lush vegetation which is accentuated by the moving sun.

Cultural significance

Anangu are the traditional Aboriginal owners of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. They believe their culture was created at the beginning of time by ancestral beings and has always existed in the Central Australian landscape. According to traditional lore, Uluru and Kata Tjuta provide physical evidence of feats performed during the creation period.

Both Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (known as The Olgas) are considered sacred sites and thus important spiritually and cermonially to the Anangu. There are more than forty named sacred sites and eleven separate Tjurkurpa (or "Dreaming") tracks in the area. Some of these dreaming tracks lead as far as the sea in all directions.

The Anangu have resided mostly in the northwest area of the state of South Australia, extending into the Northern Territory and a short distance into Western Australia. The land is an inseparable and important part of their identity, and every part of it is rich with stories and meaning to Anangu.

While political borders have generally held little meaning for indigenous peoples, the border separating the Northern Territory and South Australia served as an impediment to the Anangu in their claim to the sacred lands. The Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act was passed in 1976, meaning that after many years Aboriginal law and land rights were finally recognized in Australian law. In 1979, the Central Land Council, which represents the indigenous people predominantly in land issues, laid claim to the area that was then known the "Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park." This claim was fiercely resisted by the Northern Territory government.

After eight years of intensive lobbying by the Traditional Owners, Prime Minister Bob Hawke announced that the Federal Government intended to transfer inalienable freehold title to them. He also agreed to ten main points they had demanded in exchange for a lease-back arrangement to the Australian National Parks and Wildlife Service for a "joint-management" system in which Anangu would have a majority on the Board of Management. This was finally granted in 1985, but with the government rejecting two of the most important points the Anangu had requested: They were forced to agree to lease the Park for 99 years, instead of the fifty years originally agreed on, perhaps more importantly, they had to allow tourists to climb Uluru, which they believed was an act of desecration of one of their main dreaming tracks. Park Management has erected signs asking visitors not to climb the "Rock," but have no authority to enforce it, and many thousands of visitors are said to climb the rock every year, assisted by a chain handhold added in 1964 and extended in 1976.

In spite of the disagreements, since hand-back, Anangu and Parks Australia staff have worked together to manage the Park. Management policy and programs seek to maintain Anangu culture and heritage, conserve and protect the integrity of the ecological systems in and around the Park while providing for visitor enjoyment and educational opportunities within the Park.

Park establishment

Established as a national park in 1958 with the name "Ayers Rock-Mount Olga National Park," it has benefited under the joint-management which began in 1985. In 1987, it was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for the conservation of nature. In 1993, the official name of the Park changed to Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. In 1994, UNESCO extended its designation to recognize the park's cultural significance.

In 1995, Parks Australia and the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management won the Picasso Gold Medal, the highest UNESCO award for outstanding preservation efforts of the park. They were noted for setting new international standards for World Heritage management.

The National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1975 was replaced in July 2000, by the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The declaration of the Park was continued under the new Act.

History

In separate expeditions, William Ernest Powell Giles and William Christie Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. In 1872, while exploring the area, Ernest Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse saw Uluru and named it Ayers Rock after Sir Henry Ayers, the Chief Secretary of South Australia. Both Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Overland Telegraph Line in 1872. Further explorations followed with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for pastoralism.

In the late 1800s, interaction between Anangu and white people became more frequent as pastoralists attempted to establish themselves in the area. Due to the effects of grazing and droughts, bush food stores were depleted. Competition for these resources created conflict between the new settlers and the indigenous population. Their interactions were often violent and police patrols became more frequent.

Between 1918 and 1921, large adjoining areas of South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory were declared as Aboriginal reserves. In 1920, part of the area that was to become Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park was declared an Aboriginal Reserve (commonly known as the South-Western or Petermann Reserve) by the Australian Government under the Aboriginals Ordinance (NT).

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, Anangu became involved in dingo scalping with "doggers" who introduced Anangu to European foods and ways. The first tourists visited the Uluru area in 1936. By 1959, the first motel leases had been granted and an airstrip was built near the northern side of Uluru.

Geography and geology

From a geological point of view, analysis of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park reveals an awe-inspiring history. Five hundred million years ago, the entire area was covered by an inland sea and over many centuries, sand and mud fell to the bottom of the sea, creating rock and sandstone. Kata Tjuta's domes are the eroded remains of sedimentary rock from the seabed, while Uluru is a relic of the coarse grained, mineral-rich sandstone called arkose.

Climate and seasons

The park receives an average rainfall of 308 millimeters (12 inches) per year. Temperature extremes in the park have been recorded at 45°C (113°F) during the summer and -5°C (23°F) during winter nights.

While the Central Australian environment may at first seem stark—a barren landscape supporting spectacular rock formations—closer inspection reveals it as a complex ecosystem, full of life.

Plant and animal life have adapted to the area's extreme conditions and it subsequently supports some of the most unusual flora and fauna on the planet. Many of these have long been a valuable source of bush tucker and medicine for local Aboriginal people, who recognize six seasons:

- Piryakatu (August/September)—Animals breed and food plants flower

- Wiyaringkupai (October/November)—The really hot season when food becomes scarce

- Itanju (January/February)—Sporadic storms can roll in suddenly

- Wanitjunkupai (March)—Cooler weather

- Tjuntalpa (April/May)—Clouds roll in from the south

- Wari (June/July)—Cold season bringing morning frosts

The Park is ranked as one of the most significant arid land ecosystems in the world. As a Biosphere Reserve under the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Program, it joins an international network aiming to preserve the world's major ecosystem types.

Flora

Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park flora represents a large portion of plants found in Central Australia. There are several rare and endangered species in the Park. Most of them are restricted to the moist areas at the base of the inselbergs, which are areas of high visitor use and subject to erosion.

The desert flora has adapted to the harsh conditions. The growth and reproduction of plant communities rely on irregular rainfall. Some plants are able to survive fire and some are dependent on it to reproduce.

Plants are an important part of the indigenous spiritual traditions, many of which are associated with ancestral beings. There are special ceremonies for each of the major plant foods. Collection of plant foods remains a culturally important activity, reinforcing traditional links with country and Tjukurpa. Native specifications for the local flora include:

- "Punu"—trees

- "Puti"—shrubs

- "Tjulpun-tjulpunpa"—flowers

- "Ukiri"—grasses

Trees such as the mulga and centralian bloodwood are used to make tools such as spearheads, boomerangs and bowls. The red sap of the bloodwood is used as a disinfectant and an inhalant for coughs and colds.

Others, such as the river red gum and corkwood trees like grevillea and hakeas, are a source of food themselves. The white flaky crust from river red gum leaves can be rolled into balls and eaten like candy, while the nectar from the flowers of the corkwood trees produce a sweet drink.

Daisies and other ground flowers bloom after rain and during the winter. Others such as the wattles bloom as spring approaches. Anangu collect wattle seed, crush and mix it with water to make an edible paste which they eat raw. To make damper, the seeds are parched with hot sand so their skins can be removed before they are ground for flour.

The prickly hard spinifex hummocks have enormous root systems that prevent desert sand shifting. The hummock roots spread underground beyond the prickly clump and deeply into the soil forming an immense cone. Anangu use a resin gathered from the gummy spinifex to make gum. They thresh the spinifex until the resin particles fall free. These particles are heated until they fuse together to form a moldable black tar which is worked while warm. The gum is used for hunting and working implements, and to mend breaks in stone and wooden implements.

The naked woolybutt and native millet have seeds that are important Anangu foods. Women rub the seed heads from their stalks and then separate the seeds from the chaff by skillful winnowing. Using grinding stones, they then grind the seeds to flour for damper.

Since the European arrival in the area, 34 introduced plant species have been recorded in the Park, representing about 6.4 percent of the total park flora. Some, such as perennial buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), were intentionally introduced to rehabilitate areas damaged by erosion. It is the most threatening weed in the Park and has spread to invade water and nutrient rich drainage lines. Where infestation is dense, it prevents the growth of native grasses. A few others such as burrgrass were brought in accidentally, carried on cars and people.

Fauna

Historically, 46 species of native mammal are known to have lived in the Uluru region; currently 21 species remain, reflecting negative implications for the condition and health of the landscape. Moves are supported for the reintroduction of locally extinct animals such as mallee fowl, brushtail possum, rufous hare wallaby, or mala, bilby, burrowing bettong, and the black footed rock wallaby.

The mulgara, the only mammal listed as vulnerable, is mostly restricted to the transitional sandplain area, a narrow band of country that stretches from the vicinity of Uluru, to the Northern boundary of the Park, and into Ayers Rock Resort. This area also contains marsupial mole, woma python, or kuniya, and great desert skink.

The bat population of the Park comprises at least seven species that depend on day roosting sites within caves and crevices of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Most of the bats forage for aerial prey within an airspace extending only 100 m (328 ft) or so from the rock face.

The Park has a very rich reptile fauna of high conservation significance with 73 species having been reliably recorded. Four species of frog are abundant at the bases of Uluru and Kata Tjuta following summer rains. The great desert skink is listed as vulnerable.

Anangu continue to hunt and gather animal species in remote areas of the Park and on Anangu land elsewhere. Hunting is largely confined to the red kangaroo, Australian bustard, emu, and lizards such as the sand goanna and perentie.

Introduced species

The pressures exerted by introduced predators and herbivores on the original mammalian fauna of Central Australia were a major factor in the extinction of about 40 percent of the native species.

Of the 27 mammal species found in the Park, six are introduced: The house mouse; camel; fox; cat; dog; and rabbit. These species are distributed throughout the Park but their densities are greatest in the rich water run off areas of Uluru and Kata Tjuta.

Large numbers of rabbits led to the introduction of a rabbit control program in 1989. This has resulted in a great reduction of the rabbit population, a noticeable vegetation recovery, and a reduction in predator numbers.

Camels have been implicated in the reduction of plant species, particularly the more succulent species such as the quandong. The house mouse is a successful invader of disturbed environments and habitats that have lost native rodents.

Subjective estimates of cat and fox numbers have been collected in association with the rabbit control program. The national threat abatement programs may provide the framework for controlling them. Anangu knowledge and tracking skills are invaluable in the management of these introduced animals. The Park regulations prohibit visitors bringing animals into the Park unless they are a guide dog for the blind or deaf, or a permit is granted by the Director of National Parks.

Fire management

Fires have been a part of central desert land management for thousands of years and have shaped the landscape, habitats, survival of animals, and patterns of vegetation.

Controlled burning usually takes place during the winter months because of the cooler weather, while natural fires mostly occur in the early summer months. Natural fires are usually started by the lightning strikes of dry electrical storms from the northwest. When the storms arrive the weather is usually hot, dry and windy—conditions ideal for raging fires. Damage can be severe and widespread.

Traditional burning of the Uluru area ended when Anangu were driven from the region during the 1930s. During the 1940s rainfall was good and vegetation flourished. A fire in 1950, fed by the natural fuel grown during the previous 20 years, destroyed approximately one third of the Park's vegetation. The pattern repeated itself and in 1976, two fires burned over three-quarters of the Park. Destructive bushfires burned much of the Park, and nearby luxury accommodations at the Ayers Rock Resort were destroyed in the 2002-2003 season.

The value of traditional burning has come to be understood and today most fires in the park are lit according to land management patterns traditionally practiced by the Indigenous people. Traditional fire and land management skills enable controlled burns that will give the desired result. These skills are vital for the preservation of the central Australian ecology.

Tourism and facilities

The development of tourism infrastructure adjacent to the base of Uluru that began in the 1950s soon produced adverse environmental impacts. It was decided in the early 1970s to remove all accommodation related tourist facilities and re-establish them outside the Park.

In 1975, a reservation of 104 square kilometers (40 sq mi) of land beyond the park's northern boundary, 15 kilometers (8 mi) from Uluru, was approved for the development of a tourist facility and an associated airport, to be known as Yulara. The campground within the Park was closed in 1983 and the motels closed in late 1984, coinciding with the opening of the Yulara resort. In 1992, the majority interest in the Yulara Resort held by the Northern Territory Government was sold and the resort was renamed "Ayers Rock Resort."

Since the Park's designation as a World Heritage Site, annual visitor numbers have risen to nearly a half-million. Increased tourism provides regional and national economic benefits, as well as presents an ongoing challenge to balance conservation of cultural values and visitor needs.

There are a number of walking trails that visitors can take around the major attractions of the Park. The Base Walk is one of the best ways to see Uluru. Other walks surrounding Uluru include the Liru Walk, Mala Walk and Kuniya walk, while the sunrise and sunset viewing areas provide for a great visual experience.

Cultural traditions

The Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park Cultural Centre, located inside the Park on the main road to Uluru, provides an introduction to Tjukurpa, Anangu art, Anangu way of life (traditional and current), history, languages, wildlife, and joint management of the Park. There are also art and craft demonstrations, bush tucker sessions, plants walks and cultural presentations.

There are displays featuring photo collages, oral history sound panels, Pitjantjatjara language learning interactives, soundscapes, videos and artifacts. Explanations are provided in Pitjantjatjara, English, Italian, Japanese, German, and French.

The Uluru climb is the traditional route taken by ancestral Mala men upon their arrival in the area. Anangu do not climb Uluru because of the spiritual significance it holds for them, and have requested that visitors be educated, and thus choose to respect their law and culture by not climbing. The Cultural Centre in the Park provides such cultural information to visitors.

The Valley of the Winds walk is an alternative to climbing Uluru, and offers views of the spectacular landscape from two lookout points along the track. The walk is steep, rocky and difficult in places. For safety reasons this walk is closed under certain circumstances including heat, darkness and during rescue efforts.

The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu is inside the park area, but there are no provisions for tourists, who must stay at the resorts in the township of Yulara. The national park and town are served by Connellan Airport.

Park management

Upon the agreement to form a joint-management system in 1985, with Anangu forming the majority of the Board of Management, then Governor General Sir Ninian Stephen presented the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park title deeds back to Anangu. This act served to both acknowledge and respect their position as the land's traditional owners.

The Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management was established under the National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act (1975) on December 10, 1985, and held its first meeting on April 22, 1986. The Board of Management continues under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act of 1999.

The lease agreement ensures that the Director of National Parks:

- Has an Anangu majority on the Board of Management

- Encourages the maintenance of Anangu tradition through protection of sacred sites and other areas of significance

- Maximizes Anangu involvement in Park administration and management, and provides necessary training

- Delivers training programs to Anangu to enable them to take up employment in the Park

- Maximizes Anangu employment in the Park by accommodating Anangu needs and cultural obligations with flexible working conditions

- Uses Anangu traditional skills in Park management

- Actively supports the delivery of cross-cultural training by Anangu to Park staff, local residents and Park visitors

- Consults regularly with Anangu

- Encourages Anangu commercial activities in the Park

- Makes rental payments to the members of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta lands trust

- Maintains the Park to best practice standards

- Involves Anangu in staff selection

Of the 12 members of the Board of Management:

- Eight Aboriginal members are nominated by the Anangu traditional owners

- One member is nominated by the federal minister responsible for tourism and approved by Anangu

- One member is nominated by the federal minister responsible for the environment and approved by Anangu

- One member is nominated by the Northern Territory Government and approved by Anangu

- One member is the Director of National Parks.

Board members normally sit for a term of five years before a new nomination process takes place. All nominees are appointed by the Minister for the Environment and Water Resources after a consultation process. Board meetings are held at least four times a year with all matters discussed in both English and Pitjantjatjara and/or Yankunytjatjara.

Tjukurpa (Aboriginal wisdom of life-harmony) guides the development and interpretation of Park policy as set out in the Plan of Management. Plans of Management are developed in consultation with Anangu and a wide range of individuals and organizations associated with the Park.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hill, Barry. 1994. The Rock: Traveling to Uluru. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781863737128.

- James, Sarah. 2005. Negotiating the Climb: Uluru, a Site of Struggle or a Shared Space? Melbourne: School of Anthropology, Geography and Environmental Studies, The University of Melbourne. ISBN 9780734030849.

- Kerle, Anne. 1995. Uluru, Kata Tjuta & Watarrka = Ayers Rock, the Olgas & Kings Canyon, Northern Territory. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 9780868400556.

- Roff, Derek. 1976. Mammals of the Ayers Rock-Mt. Olga National Park. Alice Springs, N.T.: Northern Territory Reserves Board.

- Tourism NT. This site has provided some of the images contained in this article. Retrieved September 12, 2008.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.