Tariff

| Public finance |

|

| This article is part of the series: Finance and Taxation |

| Taxation |

|---|

| Ad valorem tax · Consumption tax Corporate tax · Excise Gift tax · Income tax Inheritance tax · Land value tax Luxury tax · Poll tax Property tax · Sales tax Tariff · Value added tax |

| Tax incidence |

| Flat tax · Progressive tax Regressive tax · Tax haven Tax rate |

| Economic policy |

| Monetary policy Central bank · Money supply |

| Fiscal policy Spending · Deficit · Debt |

| Trade policy Tariff · Trade agreement |

| Finance |

| Financial market Financial market participants Corporate · Personal Public · Banking · Regulation |

A tariff or customs duty is a tax levied upon goods as they cross national boundaries, usually by the government of the importing country. The words tariff, duty, and customs are generally used interchangeably.

Reasons for tariffs

Tariffs, or customs duties, may be levied on imported goods by a government either:

- to raise revenue or

- to protect domestic industries.

However, a tariff designed primarily to raise revenue may exercise a strong protective influence and a tariff levied primarily for protection may yield revenue. Therefore Gottfried Haberler in his Theory of International Trade (Haberler 1936) suggested that the best objective distinction between revenue duties and protective duties (disregarding the motives of the legislators) is to be found in their discriminatory effects as between domestic and foreign producers.

If domestically produced goods bear the same taxation as similar imported goods, or if the goods subject to duty are not produced at home, even after the duty has been levied, and if there can be no home-produced substitutes toward which demand is diverted because of the tariff, the duty is not protective.

A purely protective tariff tends to shift production away from the export industries into the protected domestic industries and those industries producing substitutes for which demand is increased.

On the other hand, a purely revenue tariff will not cause resources to be invested in industries producing the taxed goods or close substitutes for such goods, but it will divert resources from the production of export goods to the production of those goods and services upon which the additional government receipts are spent.

From the purely revenue standpoint, a country can levy an equivalent tax on domestic production, to avoid protecting it, or select a relatively small number of imported articles of general consumption and subject them to low duties so that there will be no tendency to shift resources into industries producing such taxed goods (or substitutes for them).

For instance, during the period when it was on a free-trade basis, Great Britain followed the latter practice, levying low duties on a few commodities of general consumption such as tea, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. Unintentional protection was not a major issue, because Britain could not have produced these goods domestically.

If, on the other hand, a country wishes to protect its home industries, its list of protected commodities will be long and the tariff rates high.

Classification

Tariffs may be further classified into three groups: transit duties, export duties, and import duties.

Transit duties

This type of duty is levied on commodities that originate in one country, cross another, and are consigned to a third. As the name implies, transit duties are levied by the country through which the goods pass. The most direct and immediate effect of transit duties is to reduce the amount of commodities traded internationally and raise their cost to the importing country.

Such duties are no longer important instruments of commercial policy, but, during the mercantilist period (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) and even up to the middle of the nineteenth century in some countries, they played a role in directing trade and controlling certain trade routes. The development of the German Zollverein (customs union) in the first half of the nineteenth century was partly the result of Prussia's exercise of power to levy transit duties. In 1921 the Barcelona Statute on Freedom of Transit abolished all transit duties.

Export duties

The main function of export duties was to safeguard domestic supplies rather than to raise revenue. Export duties were first introduced in England by a statute of 1275 that imposed them on hides and wool. By the middle of the seventeenth century the list of commodities subject to export duties had increased to include more than 200 articles. They were significant elements of mercantilist trade policies.

With the growth of free trade in the nineteenth century, export duties became less appealing; they were abolished in England in 1842, in France in 1857, and in Prussia in 1865. At the beginning of the twentieth century only a few countries levied export duties: for example, Spain still levied them on coke and textile waste; Bolivia and Malaya on tin; Italy on objects of art; and Romania on hides and forest products.

The neo-mercantilist revival in the 1920s and 1930s brought about a limited reappearance of export duties. In the United States, export duties were prohibited by the Constitution, mainly because of pressure from the South, which wanted no restriction on its freedom to export agricultural products.

Export duties are now generally levied by raw-material-producing countries rather than by advanced industrial countries. Differential exchange rates are sometimes used to extract revenues from export sectors. Commonly taxed exports include coffee, rubber, palm oil, and various mineral products. The state-controlled pricing policies of international cartels such as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have some of the characteristics of export duties.

Export duties may act as a form of protection to domestic industries. As examples, Norwegian and Swedish duties on exports of forest products were levied chiefly to encourage milling, woodworking, and paper manufacturing at home. Similarly, duties on the export from India of untanned hides after World War I were levied to stimulate the Indian tanning industry. In a number of cases, however, duties levied on exports from colonies were designed to protect the industries of the mother country and not those of the colony.

If the country imposing the export duty supplies only a small share of the world's exports and if competitive conditions prevail, the burden of an export duty will likely be borne by the domestic producer, who will receive the world price minus the duty and other charges. But if the country produces a significant fraction of the world output and if domestic supply is sensitive to lower net prices, then output will fall and world prices may rise and as a consequence not only domestic producers but also foreign consumers will bear the export tax. How far a country can employ export duties to exploit its monopoly position in supplying certain raw materials depends upon the success other countries have in discovering substitutes or new sources of supply.

Export duties are no longer used to a great extent, except to tax certain mineral and agricultural products. Several resource-rich countries depend upon export duties for much of their revenue.

Import duties

Import duties are the most important and most common types of custom duties. As noted above, they may be levied either for revenue or protection or both. An import tariff may be either:

- specific,

- ad valorem, or

- compound (a combination of both).

A "specific tariff" is a levy of a given amount of money per unit of the import, such as $1.00 per yard or per pound.

An "ad valorem tariff," on the other hand, is calculated as a percentage of the value of the import. Ad valorem rates furnish a constant degree of protection at all levels of price (if prices change at the same rate at home and abroad), while the real burden of specific rates varies inversely with changes in the prices of the imports.

A specific tariff, however, penalizes more severely the lower grades of an imported commodity. This difficulty can be partly avoided by an elaborate and detailed classification of imports on the basis of the stage of finishing, but such a procedure makes for extremely long and complicated tariff schedules. Specific tariffs are easier to administer than ad valorem rates, for the latter often raise difficult administrative issues with respect to the valuation of imported articles.

Import tariffs are not a satisfactory means of raising revenue because they encourage uneconomic domestic production of the dutied item. Even if imports constitute the bulk of the available revenue base, it is better to tax all consumption, rather than only consumption of imports, in order to avoid uneconomical protection.

Import tariffs are no longer an important source of revenues in developed countries. In the United States, for example, revenues from import duties in 1808 amounted to twice the total of government expenditures, while in 1837 they were less than one-third of such expenditures. Until near the end of the nineteenth century the customs receipts of the U.S. government made up about half of all its receipts. This share had fallen to about 6 percent of all receipts before the outbreak of World War II and it has since further decreased.

Arguments for import tariff protection

There are many arguments forwarded by advocates of Protectionism:

- Cheap labor

Less developed countries have a natural cost advantage as labor costs in those economies are low. They can produce goods less expensively than developed economies and their goods are more competitive in international markets.

- Infant industries

Protectionists argue that infant, or new, industries must be protected to give them time to grow and become strong enough to compete internationally, especially industries that may provide a firm foundation for future growth, such as computers and telecommunications. However, critics point out that some of these infant industries never "grow up."

- National security concerns

Any industry crucial to national security, such as producers of military hardware, should be protected. That way the nation will not have to depend on outside suppliers during political or military crises.

- Diversification of the economy

If a country channels all its resources into a few industries, no matter how internationally competitive those industries are, it runs the risk of becoming too dependent on them. Keeping weaker industries competitive through protection may help in diversifying the nation’s economy.

Analysis of Import Tariffs Effect on a Domestic Economy

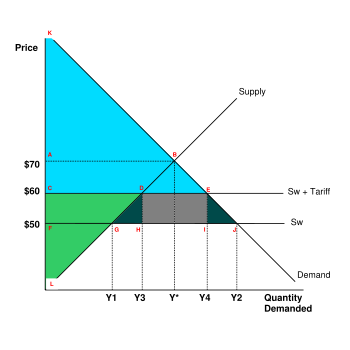

To make the above text a bit more palatable we shall produce a simple graph—of an Import Tariffs levied on a specific good in a specific country—from which we shall try to derive the economic effect on the domestic economy of that country.

In the following graph we see the effect that an import tariff has on the domestic economy. In a closed economy without trade we would see equilibrium at the intersection of the demand and supply curves (point B), yielding prices of $70 and an output of Y*.

In this case the consumer surplus would be equal to the area inside points A, B and K, while producer surplus is given as the area A, B and L. When incorporating free international trade into the model we introduce a new supply curve denoted as SW.

Under the somewhat simplistic, yet for the example permissible, assumptions—namely perfect elasticity of supply of the good and boundless quantity of world production—we assume the international price of the good is $50 (or $20 less than the domestic equilibrium price).

As a result of this price differential we see that domestic consumers will import these cheaper international alternatives, while decreasing consumption of domestic made produce. This reduction in domestic production is equal to Y* minus Y1, thus reducing producer surplus from the area A, B and L to F, G and L. This shows that domestic producers are clearly worse off with the introduction of international trade.

On the other hand, we see that consumers are now paying a lower price for the goods, which increases the consumer surplus from the area A, B and K to a new surplus of F, J and K. From this increase in consumer surplus we see that some of this surplus was, in fact, redistributed from producer surplus, equal to the area A, B, F and G.

However, the net societal gains from trade, in terms of net surplus, are equal to the area B, G and J. The level of consumption has increased from Y* to Y2, while imports are now equal to Y2 minus Y1.

Let us now introduce a tariff of $10/unit on imports. This has the effect of shifting the world supply curve vertically by $10 to SW + Tariff. Again, this will create a redistribution of surplus within the model.

We see that consumer surplus will decrease to the area C, E and K, which is a net loss of the area C, E, F and J. This now makes consumers unambiguously worse off than under a free trade regime, but still better off than under a system without trade. Producer surplus has increased, as they are now receiving an extra $10 per sale, to the area C, D and L. This is a net gain of the area C, D, F and G. With this increase in price the level of domestic production has increased from Y1 to Y3, while the level of imports has reduced to Y4 minus Y3.

The government also receives an increase in revenues as a result of the tariff equal to the area D, E, H and I. In dollar terms this figure is essentially $10*(Y4-Y3). However, with this redistribution of surplus we do see that some of the redistributed consumer surplus is lost. This loss of surplus is known as a deadweight loss, and is essentially the loss to society from the introduction of the tariff. This area is equal to the area E, I and J. The area D, G and H is a transfer from consumers to those the producers must pay to bring their product to market.

Without tariffs, only those producers/consumers able to produce the product at the world price will have the money to purchase it at that price. The small FGL triangle will be matched by an equally small mirror image triangle of consumers still able to buy. With tariffs, a larger CDL triangle and its mirror will survive.

Tariff schedule

A list of all import duties is usually known as a tariff schedule:

- A single tariff schedule, a country, such as the United States, applies to all imports regardless of the country of origin. This is to say that a single duty is listed in the column opposite the enumerated commodities.

- A double-columned or multi-columned tariff schedule provides for different rates according to the country of origin, lower rates being granted to commodities coming from countries with which tariff agreements have been negotiated. Most trade agreements are based on the most-favored-nation clause (MFN), which extends to all nations’ party to the agreement whatever concessions are granted to the MFN.

Every country has a free list that includes articles admitted without duty. By looking at the free list and the value of the goods imported into the United States under it one might be led to conclude that tariff protection is very limited, for more than half of all imports are exempt from duties. Such a conclusion, however, is not correct, for it ignores the fact that the higher the tariff, the less will be the quantity of dutiable imports.

Attempts to measure the height of a tariff wall and make international comparisons of the degree of protection, based upon the ratio of tariff receipts to the total value of imports, are beset by difficulties and have little meaning.

A better method of measuring the height of a tariff wall is to convert all duties into ad valorem figures and then estimate the weighted-average rate. The weight should reflect the relative importance of the different imports; a tariff on foodstuffs, for example, may be far more important than a tariff on luxuries consumed by a small group of people.

A more appropriate measure of protection is that of effective protection. It recognizes that the protection afforded a particular domestic industry depends on the treatment of its productive inputs, as well as its outputs. Suppose, for example, that half of the inputs to an industry are imported and subject to a duty of 100 percent. If the imports with which the industry competes are subject to a duty of less than 50 percent there is no effective protection.

Brief history of tariffs in the United States

There are two sides to the history of tariffs in the economic history of the United States and the role they have played in U.S. trade policy. In the first place, it was the single most important source of federal revenue from the 1790s to the eve of World War I, when it was finally surpassed by income taxes. So essential was this revenue source, and so easy was it to collect at the major ports, that all sides agreed that the nation should have a tariff for revenue purposes. In practice, that was an average tax of about 20 percent of the value of some imported goods. (Imports that were not taxed were "free".)

The second issue was protection to industry; it was the political dimension of the tariff. From the 1790s to the 2000s, the tariff (and closely related issues such as import quotas and trade treaties) have generated enormous political stresses. For a brief moment in 1832 South Carolina made vague threats to leave the Union over the tariff issue. But since, in the 1850s the southerners controlled tariff policy, keeping it low, and thus it was not a reason enough for secession.

1790 until after World War II

However, starting from the Tariff Act of 1789, imposing the first national source of revenue for the newly formed United States and taxing all imports at rates from 5 to 15 percent, the tariffs had gone on the political roller-coaster, depending on the political party at helm.

Consequently, the Tariff of 1828, ridiculed by free traders as the "Tariff of Abominations," with duties averaging over 50 percent gave way to Nullification Crisis and to a uniform 20 percent in 1842.

It stayed roughly at the same level until the Republican-controlled Congress doubled and tripled the rates on European goods (during the Civil War), which topped out at 49 percent in 1868.

With Democrats, especially presidential candidates had always trying for lower taxes, the Republican position could have been defined by Republican Congressman William McKinley, who argued that "Free foreign trade gives our money, our manufactures, and our markets to other nations to the injury of our labor, our tradespeople, and our farmers. Protection keeps money, markets, and manufactures at home for the benefit of our own people."

Hence, in 1897, the GOP boosted rates back to the 50 percent level.

True to the political scheme, Woodrow Wilson made a drastic lowering of tariff rates a major priority for his presidency. The 1913 Underwood Tariff cut rates, but the coming of World War I in 1914 radically revised trade patterns. Reduced trade and, especially, the new revenues generated by the federal income tax made tariffs much less important. (In fact, ever since, the U.S. tariffs have been comparatively much lower than in the last half of the nineteenth century.)

Franklin Roosevelt and the New Dealers made promises about lowering tariffs on a reciprocal country-by-country basis (which they did), hoping this would expand foreign trade (which it did not.) Frustrated, they gave much more attention to domestic remedies for the depression; by 1936 the tariff issue had faded from politics, and the revenue it raised was small. In World War II both tariffs and reciprocity were insignificant compared to trade channeled through Lend-Lease, the program under which the United States supplied war materiel to Allied nations between 1941 and 1945.

Post World War II

After the war the U.S. promoted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) established in 1947, to minimize tariffs and other restrictions, and to liberalize trade among all capitalist countries. In 1995, GATT became the World Trade Organization (WTO); with the collapse of Communism its open markets/low tariff ideology became dominant worldwide in the 1990s.

After the 1970s, for the first time there was stiff competition from low-cost producers around the globe. In the late 1970s Detroit and the auto workers union combined to fight for protection. They obtained not high tariffs, but a voluntary restriction of imports from the Japanese government.

Such restrictions in the form of quotas were two-country diplomatic agreements that had the same protective effect as high tariffs, but did not invite retaliation from third countries. The Japanese producers, limited by the number of cars they could export to America, opted to increase the value of their exports to maintain revenue growth. This action threatened the American producers' historical hold on the mid- and large-size car markets.

1980s to present

The GOP under Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush abandoned the protectionist ideology, and came out against quotas and in favor of the GATT/WTO policy of minimal economic barriers to global trade. Free trade with Canada came about as a result of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987, which led in 1994 to the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, Bill Clinton worked with Republicans to give China entry into WTO and "most favored nation" trading status (meaning low tariffs). Opposition to liberalized trade came increasingly from labor unions, but their shrinking size and diminished political clout repeatedly left them on the losing side.

WTO and developing world

NAFTA and WTO advocates promoted an optimistic vision of the future, with prosperity to be based on intellectuals skills and managerial know-how more than on routine physical labor. However, serious tariff problems and oppositions to free international trade have been experienced in the developing and/or transitional countries that have infant industries, which may not survive competition with cheap imports without tariff protection. Such countries also have a very cheap labor force—apart from unemployment and outright poverty—producing low-priced products that these countries try to “dump” onto the international market.

In particular, agriculture is of critical importance to many developing countries in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment, and thus plays a key role in meeting development objectives such as poverty alleviation and food security. Negotiations on agriculture began in 2000 under the “built-in agenda” of the Uruguay Round, with the long-term objective of establishing a fair and market-oriented trading system through a program of fundamental reform encompassing strengthened rules and specific commitments on support and protection in order to correct and prevent restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets.

The negotiations are aimed at substantial improvements in market access; reductions of, with a view to phasing out, all forms of export subsidies; and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic support. There is to be special and differential treatment for developing countries in negotiations and eventual concessions and commitments, and as appropriate in the rules and disciplines to be negotiated, so as to be operationally effective and to enable developing countries to effectively take account of their development needs, including food security and rural development.

In the language of the WTO, this "special and differential treatment" consists of delineating the permitted level of domestic support to agriculture in any specific developing country into “boxes” of different colors:

- Green box: supports considered not to distort trade and, therefore, permitted with no limits.

- Blue box: permitted supports linked to production, but subject to production limits, and therefore minimally trade-distorting.

- Amber box: supports considered to distort trade and therefore subject to reduction commitments, in other words, prohibited.

Tariffs vs. VAT (or sales tax)

Developed countries

It should also be noted that the same imports subject to a Value added tax (VAT) may also be subject to separate tariffs or custom duties. Even with the complete elimination of tariffs among European Union (EU) countries, the VAT would still be collected on all imports to achieve tax neutrality and ensure a level tax playing field for both foreign and domestic firms. The problems start when VAT countries trade with non-VAT countries.

As global trade negotiations over the past half-century have lowered tariffs on imports, global trade rules have not regulated the rate of VAT taxes that countries may apply to imports. In the 1960s, the Governments of Europe imposed a 10.4 percent average tariff on imports and only three EU nations imposed a VAT, with an average standard rate of 13.4 percent. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, the EU nations imposed an average tariff of 4.4 percent, plus an average 19.4 percent VAT equivalent tax, or a total levy of 23.8 percent on U.S. goods and service imports. The protection is the same, whatever its name.

For example, when a German car is imported to the U.S., Germany rebates the 16 percent VAT to the manufacturer, allowing the export value of the car to be $19,827.59. Moreover, when the German car is imported to the U.S. no U.S. tax comparable to the VAT is assessed, so the car is allowed to enter the U.S. market at a price under $20,000.

Solution taken into global economy

Such a differential provides a powerful incentive for U.S. (and no-VAT) -headquartered companies to shift production and jobs to nations that use a VAT. With such a shift, they get both a tax rebate on their exports into the American market and avoid double taxation (U.S. direct tax, plus national VAT) on sales in that foreign market. They pay only the VAT on local sales. Thousands of U.S. -headquartered companies are now producing and exporting goods and services from nations that use a VAT and getting the VAT tax advantage in global trade.

Developing countries

The limited administrative capacity in many developing countries suggests, however, that the implementation of the crediting arrangements of VAT is often imperfect (at least for firms other than the largest firms, which may be subject to special arrangements). Clearly there is a risk that these taxes become de facto tariffs even for formal sector firms.

A distinctive feature of a VAT is, essentially, a tax on the purchase of informal operators (who in developing countries form 40 - 60 percent of GDP) from formal sector business and, not least, on their imports. The potential importance of the creditable withholding taxes, levied by many developing countries leaves a clear conclusion:

Tariffs, even in cases of informal sector of a small economy, may not need to be employed. To preserve government revenue and increase welfare, in the face of efficiency improved tariff cuts, the conditions are established under which a VAT alone is fully optimal, precisely because it is in part a tax on informal sector production.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- “Back to Basics: Market Access Issues in the Doha agenda,” United Nations, New York and Geneva, 2003

- "international trade." Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. <http://www.britannica.com/eb/article?tocId=61697>

- Doran, Charles F. and Gregory P. Marchildon. The NAFTA Puzzle: Political Parties and Trade in North America (1994)

- Eckes, Alfred. Opening America's Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy since 1776 (1995)

- Haberler, G., The Theory of International Trade, London, 1936, (German ed. 1933)

- Kaplan, Edward S. Prelude to Trade Wars: American Tariff Policy, 1890-1922 Greenwood Press 1994

- Kaplan, Edward S. American Trade Policy: 1923-1995 (1996), online review

- Bereman, Wayne. Free Markets Deserve Protection; By Definition! The American Protectionist Society. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- Taussig, F.W. Tariff Encyclopedia Britannica (11th edition, 1911) vol 26 pp. 422-27. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

External links

- Market Access Map: Making import tariffs and market access barriers transparent

- Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Tariff Database

- Interactive Tariff and Trade Dataweb United States International Trade Commission

- Tariffs and Import Fees

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tariff history

- Import_tariff history

- Infant_industry_argument history

- Tariff_in_American_history history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.