Difference between revisions of "Resurrection" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}}{{2Copyedited}} |

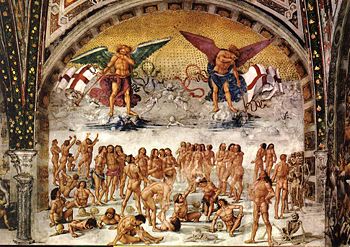

[[Image:Signorelli Resurrection.jpg|right|thumb|350px|''Resurrection of the Flesh'' (1499-1502) Fresco by Luca Signorelli<br />Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto]] | [[Image:Signorelli Resurrection.jpg|right|thumb|350px|''Resurrection of the Flesh'' (1499-1502) Fresco by Luca Signorelli<br />Chapel of San Brizio, Duomo, Orvieto]] | ||

| − | '''Resurrection''' is most commonly associated with the raising of a person from [[death]] back to [[life]] | + | '''Resurrection''' is most commonly associated with the reuniting of the [[spirit]] and body of a person in that person's [[afterlife]], or simply with the raising of a person from [[death]] back to [[life]]. What this means depends upon one's presuppositions about the nature of the human person, especially with regard to the existence of a soul or spirit counterpart to the physical body. The term can be found in the [[monotheism|monotheistic]] religions of [[Judaism]], [[Christianity]], and [[Islam]], when they happily depict the final blessing of the faithful that are resurrected in the grace of God. It does play a particularly powerful role in Christianity, as the resurrection of [[Jesus]] is its core foundation. At the same time, these religions unavoidably talk also about the unfaithful resurrected for eternal curse. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | What the nature of the resurrected body is may still be an issue. But, if the resurrection of the body is considered to restore some kind of psychosomatic unity of a human personality, it carries profoundly important implications. Recent [[philosophy|philosophers]] of religion insightfully try to connect this restored psychosomatic unity with the continuation of a personal identity beyond death. Furthermore, this resurrection discussion seems to be increasingly exploring the possibility of spiritual growth and eventual salvation through the restored psychosomatic unity beyond death. For this purpose, some Christian thinkers make a controversial use of the notion of [[reincarnation]] from Eastern religions and ancient Greek philosophy as an alternative for resurrection, and others try to develop a new Christian position to say that bodily resurrection, and not reincarnation, can make personal spiritual growth after death possible. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Judaism== | ==Judaism== | ||

| − | ===Pre- | + | ===Pre-Maccabean era=== |

| − | + | Prior to the Maccabean struggle with Antiochus Epiphanies in the second century B.C.E..E., the notion of bodily resurrection was basically absent in [[Judaism]], which, unlike Greek philosophy, did not recognize the [[immortality]] of the soul and which was also content with the idea of Sheol as the permanent abode of shades of all departed. Even so, one can still find passages in the [[Old Testament|Hebrew Bible]] that can be considered to allude to some kind of resurrection: | |

| − | Prior to the | ||

| − | *[[Book of Ezekiel|Ezekiel]]’s vision of the valley of dry bones being restored as a living army: a metaphorical prophecy that the house of Israel would one day be gathered from the nations, out of exile, to live in the land of [[Israel]] once more. | + | *[[Book of Ezekiel|Ezekiel]]’s vision of the valley of dry bones being restored as a living army: a metaphorical prophecy that the house of Israel would one day be gathered from the nations, out of exile, to live in the land of [[Israel]] once more. |

| − | * | + | * [[First Book of Samuel|1 Samuel]] 2:6, NIV—"he brings down to the grave and raises up." |

| − | * [[Book of Job|Job]] 19:26, | + | * [[Book of Job|Job]] 19:26, NIV—"after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God." |

| − | * [[Book of Isaiah|Isaiah]] 26:19, | + | * [[Book of Isaiah|Isaiah]] 26:19, NIV—"your dead will live; their bodies will rise." |

| − | * Ezekiel 37:12, | + | * Ezekiel 37:12, NIV—"I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them." |

| − | Other passages may be more ambiguous: | + | Other passages may be more ambiguous: In the Hebrew Bible, [[Elijah]] raises a young boy from death ([[First Book of the Kings|1 Kings]] 17-23), and [[Elisha]] duplicates the feat ([[Second Book of the Kings|2 Kings]] 4:34-35). There are a multiplicity of views on the scopes of these acts, including the traditional view that they represented genuine miracles and critical views that they represented resuscitations, rather than ''bona fide'' resurrections. Other common associations are the biblical accounts of the antediluvian [[Enoch (ancestor of Noah)|Enoch]] and the prophet Elijah being ushered into the presence of God without experiencing death. These, however, are more in the way of [[ascension]]s, bodily disappearances, translations, or [[apotheosis|apotheoses]] than resurrections. |

| − | === | + | ===Maccabean and Post-Maccabean era=== |

| − | + | The idea of resurrection was developed in Judaism during the Maccabean struggle. In face of death in the unbearable persecution, Jewish people desperately hoped for their resurrection as a reward for their faith: "The King of the world will raise us up, who die for his laws, in the resurrection of eternal life" (2 Maccabees 7:9).<ref>St. Talka, [http://st-takla.org/pub_Deuterocanon/Deuterocanon-Apocrypha_El-Asfar_El-Kanoneya_El-Tanya__9-Second-of-Maccabees.html The Second Book of the Maccabees.] Retrieved September 16, 2020.</ref> Hence, [[Daniel]]'s vision, where a mysterious angelic figure tells Daniel: "Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: Some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt" (Daniel 12:2, NIV). The notion of resurrection became widespread in Judaism especially among the [[Pharisees]] (but not among the [[Sadducees]]) by the first century C.E. C.F. Evans reports, "The surviving literature of the inter-testamental period shows the emergence of resurrection belief in diverse forms: Resurrection of righteous Israelites only, of righteous and unrighteous Israelites, of all men to judgment; to earth, to a transformed earth, to paradise; in a body, in a transformed body, without body."<ref>Alan Richardson and John Bowden, "Resurrection," in ''The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology'' (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983).</ref> | |

| − | The idea of resurrection was developed in Judaism during the | ||

===Orthodox Judaism=== | ===Orthodox Judaism=== | ||

| + | A famous Medieval, Jewish halakhic, legal authority, [[Maimonides]], set down thirteen main principles of the Jewish faith according to [[Orthodox Judaism]], and belief in the revival of the dead was the thirteenth. Resurrection has been printed in all Rabbinic prayer books to the present time. | ||

| − | + | The [[Talmud]] makes it one of the few required Jewish beliefs, going so far as to say that "All Israel have a share in the World to Come…but a person who does not believe in…the resurrection of the dead…has no share in the World to Come" ([[Sanhedrin (tractate)|Sanhedrin]] 50a). | |

| − | + | The second blessing of the [[Amidah]], the central thrice-daily Jewish prayer is called ''Tehiyyat ha-Metim'' ("the resurrection of the dead") and closes with the words ''m'chayei hameitim'' ("who gives life to the dead"), that is, resurrection. The Amidah is traditionally attributed to the [[Great Assembly]] of [[Ezra]]; its text was finalized in approximately its present form around the first century C.E. | |

| − | |||

| − | The second blessing of the [[Amidah]], the central thrice-daily Jewish prayer is called ''Tehiyyat ha-Metim'' ("the resurrection of the dead") and closes with the words ''m'chayei hameitim'' ("who gives life to the dead") | ||

==Christianity== | ==Christianity== | ||

| + | Christianity started as a religious movement within first century Judaism, and it retained the first-century Jewish belief in resurrection. Resurrection in Christianity refers to the resurrection of [[Jesus]] Christ, the resurrection of the [[dead]] on the [[Judgment Day]], or other instances of [[miracle|miraculous]] resurrection. | ||

| − | + | ===Resurrection of Jesus=== | |

| + | Jesus was resurrected three days after his death. A unique point about his resurrection was that it took place very soon, without waiting till the last days, although the first century Jewish belief was that resurrection would take place sometime in the future, when the [[end of time|end of the world]] would come. The resurrection of Jesus may have been the most central doctrinal position in Christianity taught to a [[Gentile]] audience. The [[Apostle]] [[Saint Paul|Paul]] said that, "if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile" ([[1 Corinthians]] 15:17, NIV). According to Paul, the entire Christian [[faith]] hinges upon the centrality of the resurrection of Jesus. Christians annually celebrate the resurrection of Jesus at [[Easter]] time. | ||

| − | ===Resurrection of | + | ===Resurrection of the dead=== |

| + | Most Christians believe that there will be a general resurrection of the dead at the end of the world, as prophesied by Paul when he said that "he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice" ([[Acts of the Apostles|Acts]] 17:31, NIV), and that "there will be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked" (Acts 24:15, NIV). The [[Book of Revelation]] also makes many references to the Day of Judgment when the dead will be raised up. Most Christians believe that if at their death the righteous and the wicked will immediately go to heaven and hell, respectively, through their resurrection the blessing of the righteous and the curse of the wicked will be intensified. A more positive side of the Christian teaching related to the resurrection of the dead, however, is that the intensified blessing of the righteous is made possible only through the [[atonement|atoning work]] of the resurrected Christ. Belief in the resurrection of the dead, and Jesus Christ's role as judge of the dead, is codified in the [[Apostles' Creed]], which is the fundamental creed of Christian baptismal faith. | ||

| − | The | + | ===Resurrection miracles=== |

| + | The resurrected Jesus Christ commissioned his followers to, among other things, raise the dead. Throughout Christian history up to the present day, there have been various accounts of Christians raising people from the dead. | ||

| − | + | In the [[New Testament]], [[Jesus]] is said to have raised several persons from death, including the daughter of Jairus shortly after death, a young man in the midst of his own [[funeral]] procession, and [[Lazarus]], who had been buried for four days. According to the [[Gospel of Matthew]], after Jesus' resurrection, many of the dead [[saint]]s came out of their tombs and entered [[Jerusalem]], where they appeared to many. Similar resuscitations are credited to Christian [[apostle]]s and saints. [[Saint Peter|Peter]] raised a woman named Dorcas (called [[Tabitha]]), and [[Saint Paul|Paul]] restored a man named [[Eutychus]], who had fallen asleep and fell from a window to his death, according to the Book of Acts. Following the apostolic era, many saints were known to resurrect the dead, as recorded in Orthodox Christian hagiographies. Faith healer William M. Branham<ref>[http://www.williambranhamhomepage.org/bblife2.htm Highlights In The Life Of William Marrion Branham] Retrieved September 16, 2020.</ref> and evangelical missionary David L. Hogan<ref>[https://freedom-ministries.us/ Freedom Ministries] Retrieved September 16, 2020.</ref> in the twentieth century claimed to have raised the dead. | |

| − | + | ==Islam== | |

| + | A fundamental tenet of Islam is belief in the day of the resurrection ''(Qiyamah)''. Bodily resurrection is heavily insisted upon in the [[Qur'an]], which challenges the Pre-Islamic Arabian concept of death.<ref>Cyril Glasse (ed.), "Resurrection," in ''The New Encyclopedia of Islam: Revised Edition of the Concise Encyclopedia of Islam'' (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2001).</ref> Resurrection is followed by judgment of all souls. The trials and tribulations of the resurrection are explained in both the Qur'an and the [[Hadith]], as well as in the commentaries of Islamic scholars such as [[al-Ghazali]], Ibn Kathir, and Muhammad al-Bukhari. | ||

| − | + | Muslims believe that God will hold every human, Muslim and non-Muslim, accountable for his or her deeds at a preordained time unknown to humans. The [[archangel]] Israfil will sound a horn sending out a "blast of truth." Traditions say [[Muhammad]] will be the first to be brought back to life. | |

| − | + | According to the Qur'an, sins that can consign someone to [[hell]] include lying, dishonesty, corruption, ignoring God or God's revelations, denying the resurrection, refusing to feed the poor, indulgence in opulence and ostentation, the economic exploitation of others, and social oppression. The punishments in hell includes ''adhab'' (a painful punishment of torment) and ''khizy'' (shame or disgrace). | |

| − | + | The punishments in the Qur'an are contrasted not with release but with mercy. Islam views [[paradise]] as a place of joy and bliss. Islamic descriptions of paradise are described as physical pleasures, sometimes interpreted literally, sometimes allegorically. | |

| − | + | ==Theological issues== | |

| + | There are a few [[theology|theological]] issues related to resurrection more sharply identified and more explicitly discussed in [[Christianity]] than in [[Judaism]] and [[Islam]]. | ||

| − | In | + | First of all, what is the real meaning of the resurrection of the body? Is it the precise resuscitation of the same physical body as before? Yes, it is, if it concerns above-mentioned resurrection miracles in Christianity (as well as in Judaism) in which the same physical body is still there without decaying. But, what if the body decays and its elements disperse long after its death? In this case, only some Christians believe that still the very same earthly body will come back. Most Christians reject it in favor of [[Saint Paul|Paul]]'s assertion that bodily resurrection means to assume an "imperishable," "glorified," "spiritual body" (1 Corinthians 15:42-44), similar to [[Jesus]] in his resurrected state. It is "a body of a new order, the perfect instrument of the spirit, raised above the limitations of the earthly body, with which it will be identical only in the sense that it will be the recognizable organism of the same personality."<ref>F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, "Resurrection of the Dead," in ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).</ref> |

| − | + | Second, when does bodily resurrection happen? Paul has two different answers. His first answer is that it takes place immediately after physical death ([[Second Epistle to the Corinthians|2 Corinthians]] 5:1-4). His second answer is that it will take place on the [[Day of Judgment]] in the [[last days]] (1 Corinthians 15:51-52; [[First Epistle to the Thessalonians|1 Thessalonians]] 4:16-17). Usually, Christianity (as well as Judaism and Islam) supports the second answer. But, if the resurrection of Jesus took place almost immediately after his death, it stands to reason that human resurrection may also take place immediately after physical death, following Paul's first answer. Also, if Paul's second answer were correct, there would be a long period of time from the moment of physical death until the last days, during which the soul would have to await its bodily resurrection—a period which is called the "[[intermediate state]]," or the state of "soul-sleep," in Christian theology. In this state, the soul would have no physical counterpart coupled with it, and it would make a personal identity impossible. This can become quite a strong reason to argue that bodily resurrection should take place immediately after death and not in the last days. | |

| − | + | A third issue is the continuation of a personal identity beyond death. As was noted above, one benefit of resurrection is "the recognizable organism of the same personality." In the words of Alan Richardson, "The idea of 'the resurrection of the body'…was the natural Hebraic manner of speaking about the risen life of Christians with Christ: It is in the body that persons are recognizable as individuals with their own personal identity. Hence, 'resurrection of the body' means resurrection after death to a fully personal life with Christ in God."<ref>Alan Richardson (ed.), "Resurrection of the Body," in ''A Dictionary of Christian Theology'' (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969).</ref> The notion of a personal identity made possible by bodily resurrection is in agreement with the basic philosophical tenet of [[Thomas Aquinas]] that the individuation of "form" is made possible by "matter" that is coupled with "form." Just like there would be no individuation without matter, there also would be no personal identity without resurrection. The question is: Did God arrange humanity in the created world, so people might ''always'' enjoy personal identity? Or would God allow personal identity to be interrupted at times? If God created people as unique creatures in this world, it seems that he would not allow their unique identity to be destroyed even for a moment. | |

| − | + | ==Personal growth beyond death== | |

| + | There is still another important resurrection-related issue which the Abrahamic religions seem to have a considerable difficulty in addressing. It is about personal spiritual growth and salvation after physical death. Although the Bible suggests that Jesus, while in the tomb for three days, descended to [[Hades]] to preach to the "spirits in prison" there for their possible salvation (1 Peter 3:18-20), nevertheless most Christian Churches teach that once one dies, he will not be able to spiritually grow for salvation any more. At physical death, the righteous will immediately go to heaven and the wicked to hell. In the last days when they have bodily resurrection, their respective blessing and curse will be made more intense. The only exceptions are "[[purgatory]]" and "''limbus patrum''" ("limbo of the fathers"), as understood in the [[Catholic Church]]. Purgatory is understood to be a place of cleansing for those who do not go to heaven nor to hell due to their venial sins, and the "''limbus patrum''" is a place of Hebrew forefathers such as [[Jacob]] and [[Moses]] until the coming of Christ, at which they are finally allowed to participate in Christian [[salvation]] ([[Epistle to the Hebrews|Hebrews]] 11:39-40). Thus, conventional Christianity has no room for the spiritual growth and eventual salvation of the wicked, once they die. Even their bodily resurrection does not help; it only intensifies their curse. Some say that this can hardly justify the love of God. | ||

| − | + | If, as was noted previously, a continued personal identity is one benefit of resurrection, can't personal growth toward possible salvation be another benefit of resurrection? Religions such as [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]] can answer this question in the affirmative because their teachings of [[reincarnation]] as an alternative for resurrection can secure the personal growth of the soul through repeated life on the earth. In an effort to justify the love of God, therefore, some recent Christian thinkers adopted reincarnation to Christian theology.<ref>Geddes MacGregor, ''Reincarnation as a Christian Hope'' (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1982).</ref> Whether reincarnation actually happens or not is a much debated question, especially among Christians. | |

| − | + | But, these days the possibility of an imperfect person's spiritual growth beyond death being brought forth through resurrection (and not through reincarnation) is increasingly voiced even by Christian thinkers.<ref>John Hick, "Life after Death," in ''The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology'' (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983).</ref> If bodily resurrection brings back an imperfect person's psychosomatic status even after death, it enables that imperfect person to somehow relate to, and receive a merit from, a righteous earthly person because that earthly person naturally has a similar psychosomatic unity already. This can be how the imperfect person, and even the wicked, can still grow for possible salvation even beyond death. | |

| − | + | The Bible seems to support this, when it talks about the bodily resurrection of the imperfect Old Testament saints (Matthew 27:52-53) and their salvation through earthly believers in Christ: "These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect" (Hebrews 11:39-40, NIV). Hopefully the salvation of the wicked who passed away may also be possible in the same way, however odd it may sound. | |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| Line 83: | Line 75: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *Bynum, Caroline Walker. ''The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336.'' New York: Columbia University Press, 1995. ISBN 0231081278 |

| − | * | + | *Cross, F. L. and E.A. Livingstone (eds.). ''The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 0192115456 |

| − | * | + | *Glassé, Cyril (ed.). ''The New Encyclopedia of Islam: Revised Edition of the Concise Encyclopedia of Islam''. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2001. ISBN 0759101892 |

| − | * | + | *MacGregor, Geddes. ''Reincarnation as a Christian Hope''. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1982. ISBN 0333319869 |

| − | * | + | *McCabe, Joseph. [http://www.2think.org/hundredsheep/bible/library/myth.shtml The Myth of the Resurrection.] Retrieved September 16, 2020. |

| + | *Richardson, Alan (ed.). ''A Dictionary of Christian Theology'' Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969. | ||

| + | *Richardson, Alan and John Bowden (eds.). ''The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology''. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983. ISBN 0664213987 | ||

| + | *Wright, Tom. ''The Resurrection of the Son of God''. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0800626796 | ||

| + | *Zakydalsky, Taras. "N. F. Fyodorov's Philosophy of Physical Resurrection." Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College, 1976. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved December 8, 2022. | |

| − | *[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=233&letter=R Jewish Encyclopedia | + | *[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=233&letter=R Resurrection,] Jewish Encyclopedia. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12792a.htm General Resurrection,] The Catholic Encyclopedia. |

| − | + | *[http://www.comparativereligion.com/reincarnation.html Reincarnation: Its Meaning and Consequences.] | |

| − | *[http://www. | + | |

| − | |||

| Line 101: | Line 96: | ||

[[Category: Philosophy]] | [[Category: Philosophy]] | ||

| − | {{credit| | + | {{credit|Resurrection|138386841|Islamic_eschatology|137296564}} |

Latest revision as of 19:58, 8 December 2022

Resurrection is most commonly associated with the reuniting of the spirit and body of a person in that person's afterlife, or simply with the raising of a person from death back to life. What this means depends upon one's presuppositions about the nature of the human person, especially with regard to the existence of a soul or spirit counterpart to the physical body. The term can be found in the monotheistic religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, when they happily depict the final blessing of the faithful that are resurrected in the grace of God. It does play a particularly powerful role in Christianity, as the resurrection of Jesus is its core foundation. At the same time, these religions unavoidably talk also about the unfaithful resurrected for eternal curse.

What the nature of the resurrected body is may still be an issue. But, if the resurrection of the body is considered to restore some kind of psychosomatic unity of a human personality, it carries profoundly important implications. Recent philosophers of religion insightfully try to connect this restored psychosomatic unity with the continuation of a personal identity beyond death. Furthermore, this resurrection discussion seems to be increasingly exploring the possibility of spiritual growth and eventual salvation through the restored psychosomatic unity beyond death. For this purpose, some Christian thinkers make a controversial use of the notion of reincarnation from Eastern religions and ancient Greek philosophy as an alternative for resurrection, and others try to develop a new Christian position to say that bodily resurrection, and not reincarnation, can make personal spiritual growth after death possible.

Judaism

Pre-Maccabean era

Prior to the Maccabean struggle with Antiochus Epiphanies in the second century B.C.E., the notion of bodily resurrection was basically absent in Judaism, which, unlike Greek philosophy, did not recognize the immortality of the soul and which was also content with the idea of Sheol as the permanent abode of shades of all departed. Even so, one can still find passages in the Hebrew Bible that can be considered to allude to some kind of resurrection:

- Ezekiel’s vision of the valley of dry bones being restored as a living army: a metaphorical prophecy that the house of Israel would one day be gathered from the nations, out of exile, to live in the land of Israel once more.

- 1 Samuel 2:6, NIV—"he brings down to the grave and raises up."

- Job 19:26, NIV—"after my skin has been destroyed, yet in my flesh I will see God."

- Isaiah 26:19, NIV—"your dead will live; their bodies will rise."

- Ezekiel 37:12, NIV—"I am going to open your graves and bring you up from them."

Other passages may be more ambiguous: In the Hebrew Bible, Elijah raises a young boy from death (1 Kings 17-23), and Elisha duplicates the feat (2 Kings 4:34-35). There are a multiplicity of views on the scopes of these acts, including the traditional view that they represented genuine miracles and critical views that they represented resuscitations, rather than bona fide resurrections. Other common associations are the biblical accounts of the antediluvian Enoch and the prophet Elijah being ushered into the presence of God without experiencing death. These, however, are more in the way of ascensions, bodily disappearances, translations, or apotheoses than resurrections.

Maccabean and Post-Maccabean era

The idea of resurrection was developed in Judaism during the Maccabean struggle. In face of death in the unbearable persecution, Jewish people desperately hoped for their resurrection as a reward for their faith: "The King of the world will raise us up, who die for his laws, in the resurrection of eternal life" (2 Maccabees 7:9).[1] Hence, Daniel's vision, where a mysterious angelic figure tells Daniel: "Multitudes who sleep in the dust of the earth will awake: Some to everlasting life, others to shame and everlasting contempt" (Daniel 12:2, NIV). The notion of resurrection became widespread in Judaism especially among the Pharisees (but not among the Sadducees) by the first century C.E. C.F. Evans reports, "The surviving literature of the inter-testamental period shows the emergence of resurrection belief in diverse forms: Resurrection of righteous Israelites only, of righteous and unrighteous Israelites, of all men to judgment; to earth, to a transformed earth, to paradise; in a body, in a transformed body, without body."[2]

Orthodox Judaism

A famous Medieval, Jewish halakhic, legal authority, Maimonides, set down thirteen main principles of the Jewish faith according to Orthodox Judaism, and belief in the revival of the dead was the thirteenth. Resurrection has been printed in all Rabbinic prayer books to the present time.

The Talmud makes it one of the few required Jewish beliefs, going so far as to say that "All Israel have a share in the World to Come…but a person who does not believe in…the resurrection of the dead…has no share in the World to Come" (Sanhedrin 50a).

The second blessing of the Amidah, the central thrice-daily Jewish prayer is called Tehiyyat ha-Metim ("the resurrection of the dead") and closes with the words m'chayei hameitim ("who gives life to the dead"), that is, resurrection. The Amidah is traditionally attributed to the Great Assembly of Ezra; its text was finalized in approximately its present form around the first century C.E.

Christianity

Christianity started as a religious movement within first century Judaism, and it retained the first-century Jewish belief in resurrection. Resurrection in Christianity refers to the resurrection of Jesus Christ, the resurrection of the dead on the Judgment Day, or other instances of miraculous resurrection.

Resurrection of Jesus

Jesus was resurrected three days after his death. A unique point about his resurrection was that it took place very soon, without waiting till the last days, although the first century Jewish belief was that resurrection would take place sometime in the future, when the end of the world would come. The resurrection of Jesus may have been the most central doctrinal position in Christianity taught to a Gentile audience. The Apostle Paul said that, "if Christ has not been raised, your faith is futile" (1 Corinthians 15:17, NIV). According to Paul, the entire Christian faith hinges upon the centrality of the resurrection of Jesus. Christians annually celebrate the resurrection of Jesus at Easter time.

Resurrection of the dead

Most Christians believe that there will be a general resurrection of the dead at the end of the world, as prophesied by Paul when he said that "he has set a day when he will judge the world with justice" (Acts 17:31, NIV), and that "there will be a resurrection of both the righteous and the wicked" (Acts 24:15, NIV). The Book of Revelation also makes many references to the Day of Judgment when the dead will be raised up. Most Christians believe that if at their death the righteous and the wicked will immediately go to heaven and hell, respectively, through their resurrection the blessing of the righteous and the curse of the wicked will be intensified. A more positive side of the Christian teaching related to the resurrection of the dead, however, is that the intensified blessing of the righteous is made possible only through the atoning work of the resurrected Christ. Belief in the resurrection of the dead, and Jesus Christ's role as judge of the dead, is codified in the Apostles' Creed, which is the fundamental creed of Christian baptismal faith.

Resurrection miracles

The resurrected Jesus Christ commissioned his followers to, among other things, raise the dead. Throughout Christian history up to the present day, there have been various accounts of Christians raising people from the dead.

In the New Testament, Jesus is said to have raised several persons from death, including the daughter of Jairus shortly after death, a young man in the midst of his own funeral procession, and Lazarus, who had been buried for four days. According to the Gospel of Matthew, after Jesus' resurrection, many of the dead saints came out of their tombs and entered Jerusalem, where they appeared to many. Similar resuscitations are credited to Christian apostles and saints. Peter raised a woman named Dorcas (called Tabitha), and Paul restored a man named Eutychus, who had fallen asleep and fell from a window to his death, according to the Book of Acts. Following the apostolic era, many saints were known to resurrect the dead, as recorded in Orthodox Christian hagiographies. Faith healer William M. Branham[3] and evangelical missionary David L. Hogan[4] in the twentieth century claimed to have raised the dead.

Islam

A fundamental tenet of Islam is belief in the day of the resurrection (Qiyamah). Bodily resurrection is heavily insisted upon in the Qur'an, which challenges the Pre-Islamic Arabian concept of death.[5] Resurrection is followed by judgment of all souls. The trials and tribulations of the resurrection are explained in both the Qur'an and the Hadith, as well as in the commentaries of Islamic scholars such as al-Ghazali, Ibn Kathir, and Muhammad al-Bukhari.

Muslims believe that God will hold every human, Muslim and non-Muslim, accountable for his or her deeds at a preordained time unknown to humans. The archangel Israfil will sound a horn sending out a "blast of truth." Traditions say Muhammad will be the first to be brought back to life.

According to the Qur'an, sins that can consign someone to hell include lying, dishonesty, corruption, ignoring God or God's revelations, denying the resurrection, refusing to feed the poor, indulgence in opulence and ostentation, the economic exploitation of others, and social oppression. The punishments in hell includes adhab (a painful punishment of torment) and khizy (shame or disgrace).

The punishments in the Qur'an are contrasted not with release but with mercy. Islam views paradise as a place of joy and bliss. Islamic descriptions of paradise are described as physical pleasures, sometimes interpreted literally, sometimes allegorically.

Theological issues

There are a few theological issues related to resurrection more sharply identified and more explicitly discussed in Christianity than in Judaism and Islam.

First of all, what is the real meaning of the resurrection of the body? Is it the precise resuscitation of the same physical body as before? Yes, it is, if it concerns above-mentioned resurrection miracles in Christianity (as well as in Judaism) in which the same physical body is still there without decaying. But, what if the body decays and its elements disperse long after its death? In this case, only some Christians believe that still the very same earthly body will come back. Most Christians reject it in favor of Paul's assertion that bodily resurrection means to assume an "imperishable," "glorified," "spiritual body" (1 Corinthians 15:42-44), similar to Jesus in his resurrected state. It is "a body of a new order, the perfect instrument of the spirit, raised above the limitations of the earthly body, with which it will be identical only in the sense that it will be the recognizable organism of the same personality."[6]

Second, when does bodily resurrection happen? Paul has two different answers. His first answer is that it takes place immediately after physical death (2 Corinthians 5:1-4). His second answer is that it will take place on the Day of Judgment in the last days (1 Corinthians 15:51-52; 1 Thessalonians 4:16-17). Usually, Christianity (as well as Judaism and Islam) supports the second answer. But, if the resurrection of Jesus took place almost immediately after his death, it stands to reason that human resurrection may also take place immediately after physical death, following Paul's first answer. Also, if Paul's second answer were correct, there would be a long period of time from the moment of physical death until the last days, during which the soul would have to await its bodily resurrection—a period which is called the "intermediate state," or the state of "soul-sleep," in Christian theology. In this state, the soul would have no physical counterpart coupled with it, and it would make a personal identity impossible. This can become quite a strong reason to argue that bodily resurrection should take place immediately after death and not in the last days.

A third issue is the continuation of a personal identity beyond death. As was noted above, one benefit of resurrection is "the recognizable organism of the same personality." In the words of Alan Richardson, "The idea of 'the resurrection of the body'…was the natural Hebraic manner of speaking about the risen life of Christians with Christ: It is in the body that persons are recognizable as individuals with their own personal identity. Hence, 'resurrection of the body' means resurrection after death to a fully personal life with Christ in God."[7] The notion of a personal identity made possible by bodily resurrection is in agreement with the basic philosophical tenet of Thomas Aquinas that the individuation of "form" is made possible by "matter" that is coupled with "form." Just like there would be no individuation without matter, there also would be no personal identity without resurrection. The question is: Did God arrange humanity in the created world, so people might always enjoy personal identity? Or would God allow personal identity to be interrupted at times? If God created people as unique creatures in this world, it seems that he would not allow their unique identity to be destroyed even for a moment.

Personal growth beyond death

There is still another important resurrection-related issue which the Abrahamic religions seem to have a considerable difficulty in addressing. It is about personal spiritual growth and salvation after physical death. Although the Bible suggests that Jesus, while in the tomb for three days, descended to Hades to preach to the "spirits in prison" there for their possible salvation (1 Peter 3:18-20), nevertheless most Christian Churches teach that once one dies, he will not be able to spiritually grow for salvation any more. At physical death, the righteous will immediately go to heaven and the wicked to hell. In the last days when they have bodily resurrection, their respective blessing and curse will be made more intense. The only exceptions are "purgatory" and "limbus patrum" ("limbo of the fathers"), as understood in the Catholic Church. Purgatory is understood to be a place of cleansing for those who do not go to heaven nor to hell due to their venial sins, and the "limbus patrum" is a place of Hebrew forefathers such as Jacob and Moses until the coming of Christ, at which they are finally allowed to participate in Christian salvation (Hebrews 11:39-40). Thus, conventional Christianity has no room for the spiritual growth and eventual salvation of the wicked, once they die. Even their bodily resurrection does not help; it only intensifies their curse. Some say that this can hardly justify the love of God.

If, as was noted previously, a continued personal identity is one benefit of resurrection, can't personal growth toward possible salvation be another benefit of resurrection? Religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism can answer this question in the affirmative because their teachings of reincarnation as an alternative for resurrection can secure the personal growth of the soul through repeated life on the earth. In an effort to justify the love of God, therefore, some recent Christian thinkers adopted reincarnation to Christian theology.[8] Whether reincarnation actually happens or not is a much debated question, especially among Christians.

But, these days the possibility of an imperfect person's spiritual growth beyond death being brought forth through resurrection (and not through reincarnation) is increasingly voiced even by Christian thinkers.[9] If bodily resurrection brings back an imperfect person's psychosomatic status even after death, it enables that imperfect person to somehow relate to, and receive a merit from, a righteous earthly person because that earthly person naturally has a similar psychosomatic unity already. This can be how the imperfect person, and even the wicked, can still grow for possible salvation even beyond death.

The Bible seems to support this, when it talks about the bodily resurrection of the imperfect Old Testament saints (Matthew 27:52-53) and their salvation through earthly believers in Christ: "These were all commended for their faith, yet none of them received what had been promised. God had planned something better for us so that only together with us would they be made perfect" (Hebrews 11:39-40, NIV). Hopefully the salvation of the wicked who passed away may also be possible in the same way, however odd it may sound.

Notes

- ↑ St. Talka, The Second Book of the Maccabees. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ↑ Alan Richardson and John Bowden, "Resurrection," in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983).

- ↑ Highlights In The Life Of William Marrion Branham Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ↑ Freedom Ministries Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- ↑ Cyril Glasse (ed.), "Resurrection," in The New Encyclopedia of Islam: Revised Edition of the Concise Encyclopedia of Islam (Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2001).

- ↑ F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, "Resurrection of the Dead," in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977).

- ↑ Alan Richardson (ed.), "Resurrection of the Body," in A Dictionary of Christian Theology (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969).

- ↑ Geddes MacGregor, Reincarnation as a Christian Hope (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1982).

- ↑ John Hick, "Life after Death," in The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bynum, Caroline Walker. The Resurrection of the Body in Western Christianity, 200-1336. New York: Columbia University Press, 1995. ISBN 0231081278

- Cross, F. L. and E.A. Livingstone (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977. ISBN 0192115456

- Glassé, Cyril (ed.). The New Encyclopedia of Islam: Revised Edition of the Concise Encyclopedia of Islam. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press, 2001. ISBN 0759101892

- MacGregor, Geddes. Reincarnation as a Christian Hope. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1982. ISBN 0333319869

- McCabe, Joseph. The Myth of the Resurrection. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

- Richardson, Alan (ed.). A Dictionary of Christian Theology Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1969.

- Richardson, Alan and John Bowden (eds.). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Theology. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983. ISBN 0664213987

- Wright, Tom. The Resurrection of the Son of God. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2003. ISBN 0800626796

- Zakydalsky, Taras. "N. F. Fyodorov's Philosophy of Physical Resurrection." Ph.D. diss., Bryn Mawr College, 1976.

External links

All links retrieved December 8, 2022.

- Resurrection, Jewish Encyclopedia.

- General Resurrection, The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Reincarnation: Its Meaning and Consequences.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.