RMS Titanic

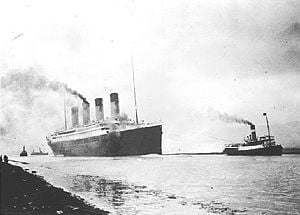

The RMS Titanic leaving Belfast for sea trials, 2 April 1912 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Class and type: | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Builder: | Harland and Wolff shipyard, Belfast |

| Laid down: | 31 March 1909 |

| Launched: | 31 May 1911 |

| Christened: | Not christened, as per White Star Line practice |

| Status: | Sunk struck iceberg at 23:40 (ship's time) on 14 April 1912 sank the next day at 2:20. After 73 years the wreck was discovered on September 1, 1985, 12,500 feet beneath the North Atlantic at 41 degrees 43' 32"N, 49 degrees 56' 49"W. |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 52,310 L/T |

| Length: | 882 feet 9 inches (269 m) |

| Beam: | 92 feet 6 inches (28 m) |

| Draught: | 34 feet 7 inches (10.5 m) |

| Propulsion: | 25 double-ended and 4 single-ended Scotch boilers at 215 psi. Two four-cylinder triple-expansion reciprocating engines each producing 15,000 hp (12 MW) at a speed of 75 rpm for outer two propellers. One low-pressure (about 7 psi absolute) steam turbine producing 16,000 hp (13.5 MW) for the centre propeller at 165 rpm. Total 46,000 hp at 75 rpm; 59,000 hp at 83 rpm (37 MW). Two bronze triple-blade side propellers. |

| Speed: | – service speed: 21 knots (40.6 km/h) (24.5 mph) – top speed: 23 knots (42.6 km/h) (26.5 mph) |

| Complement: | 2,208 (maiden voyage) First-class: 324 Second-class: 285 Third-class: 708 Crew: 891 Survivors: 712 (estimate) |

The RMS Titanic, a British Olympic-class ocean liner, became famous as the largest ocean liner built in her day and also for sinking on her maiden voyage in 1912 with a tremendous loss of life.

Building and design

In the early part of the 20th century, White Star Line sought to compete with the rival Cunard Line which then dominated the luxury niche for Atlantic transit, with the large and opulent Lusitania and Mauretania, which were the fastest and largest liners afloat.

White Star ordered three ships to provide a weekly express service with the goal of dominating the transatlantic travel business. The Olympic and Titanic at 882 feet long were larger, but not as fast as the Cunard liners. The third ship, to be named Gigantic, was just over 900 feet long; however, the name was changed to Britannic prior to completion. These larger ships offered greater amenities than the Cunard sister ships.

Titanic was designed by Harland and Wolff chairman William Pirrie, head of Harland and Wolff's design department Thomas Andrews, and general manager Alexander Carlisle, with the plans regularly sent to the White Star Line's managing director J. Bruce Ismay for suggestions and approval. Construction of the Titanic, funded by the American J.P. Morgan and his International Mercantile Marine Co., began on 31 March 1909. Titanic No. 401 was launched two years and two months later on 31 May 1911. Titanic's outfitting was completed on 31 March the following year.

Titanic was 882 feet 9 inches (269 m) long and 92 feet 6 inches (28 m) at the beam. She had a Gross Register Tonnage of 46,328 tons, and a height from the water line to the boat deck of 60 feet (18 m).Her three propellers were driven by two four-cylinder, triple-expansion, inverted reciprocating steam engines and one low-pressure Parsons turbine.Steam was provided by 25 double-ended and 4 single-ended Scotch-type boilers fired by 159 coal burning furnaces that made possible a top speed of 23 knots (43 km/h). Only three of the four 63 foot (19 m) tall funnels were functional; the fourth, which served only as a vent, was added to make the ship look more impressive. Titanic could carry a total of 3,547 passengers and crew and, because she carried mail, her name was given the prefix RMS, (Royal Mail Steamer).

Contemporaries considered the Titanic the pinnacle of naval architecture and technological achievement, and she was thought by The Shipbuilder magazine to be "practically unsinkable."[1] Titanic had a double-bottom hull, containing 44 tanks for boiler water and ballast to keep the ship safely balanced at sea (later ships also had a double-walled hull). Titanic exceeded the lifeboat standard, with 20 lifeboats (though not enough for all passengers). Titanic was divided into 15 compartments. Dividing doors were held up in the open position by electro-magnetic latches that could be closed by a switch on the ship's bridge and by a float system installed on the door itself.

Fixtures and fittings

In her time, Titanic surpassed all rivals in luxury and opulence. She offered an onboard swimming pool, a gymnasium, a Turkish bath, libraries for each passenger class, and a squash court. First-class common rooms were adorned with elaborate wood panelling, expensive furniture and other decorations. In addition, the Café Parisien offered superb cuisine for the first-class passengers, with a sunlit veranda fitted with trellis decorations. The ship incorporated technologically advanced features for the period. She had an extensive electrical subsystem with steam-powered generators and ship-wide electrical wiring feeding electric lights. She also boasted two wireless Marconi sets, including a powerful 1,500-watt radio manned by operators who worked in shifts, allowing constant contact and the transmission of many passenger messages.

Comparisons with the Olympic

The Titanic closely resembled her older sister Olympic but there were a few differences. Two of the most noticeable were that half of the Titanic's forward promenade A-Deck (below the lifeboat deck) was enclosed against outside weather, and her B-Deck configuration was completely different from the Olympic's. The Titanic had a specialty restaurant called Café Parisien, a feature that the Olympic did not have until 1913. Some of the flaws found on the Olympic, such as the creaking of the aft expansion joint, were corrected on the Titanic. The skid lights that provided natural illumination on A-deck were round, while on Olympic they were oval. The Titanic's wheelhouse was made narrower and longer than the Olympic's.[2] These, and other modifications, made the Titanic 1,004 gross tons larger than the Olympic.

Passengers and crew

Crew

The Titanic was captained by Commander Edward John Smith, the White Star Line's most prized captain. The ship's original chief officer was to be William Murdoch, but he was demoted to first officer after Smith brought with him his chief officer from the Olympic, Henry T. Wilde.

The rest of the ship's officers were Second Officer Charles Lightoller, Third Officer Herbert Pitman, Fourth Officer Joseph Boxhall, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe and Sixth Officer James Moody.

Passengers

The first-class passengers for Titanic's maiden voyage included some of the richest and most prominent people in the world. They included millionaire John Jacob Astor IV and his pregnant wife Madeleine;industrialist Benjamin Guggenheim; Macy's department store owner Isidor Straus and his wife Ida; Denver millionaire Margaret "Molly" Brown; Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon and his wife, couturière Lady Duff-Gordon; streetcar magnate George Dunton Widener; Pennsylvania Railroad executive John Borland Thayer and 17-year-old son, Jack;journalist William Thomas Stead; Charles Hays, president of Canada's Grand Trunk Railway, ; the Countess of Rothes; United States presidential aide Major Archibald Butt; author and socialite Helen Churchill Candee; author Jacques Futrelle, and their friends, Broadway producers Henry and Rene Harris; writer and painter Francis Davis Millet; pioneer aviation entrepreneur Pierre Maréchal Sr.; American silent film actress Dorothy Gibson, White Star Line's Managing Director J. Bruce Ismay and from Harland & Wolff builder Thomas Andrews

Second-class passengers included journalist Lawrence Beesley, Father Thomas R.D. Byles, a Catholic priest on his way to the United States to officiate at his younger brother's wedding. Michel Navratil, a Frenchman who had kidnapped his two sons, Michel Jr. and Edmond, and Sylvia Mae Caldwell, who later married the founder of State Farm Insurance George J. Mecherle. Both J. P. Morgan and Milton S. Hershey had plans to travel on the Titanic but canceled their reservations before the voyage.

In 2007, scientists using DNA analysis identified the body of an unknown child recovered shortly after the incident as Sidney Leslie Goodwin, a 19-month-old boy from England. Goodwin, along with his parents and five siblings, boarded in Southampton, England, as third-class passengers.

Disaster

On April 10, 1912, the Titanic left Southampton, England and traveled to Cherbourg, France where many first-class passengers boarded. On April 11, 1912, the Titanic left Cherbourg en route to Queenstown (Cobh), Ireland where the Titanic picked up the majority of its third-class passengers. On April 12, 1912, the Titanic left on its maiden voyage across the Atlantic Ocean and was due to arrive in New York City on Wednesday April 17, 1912.

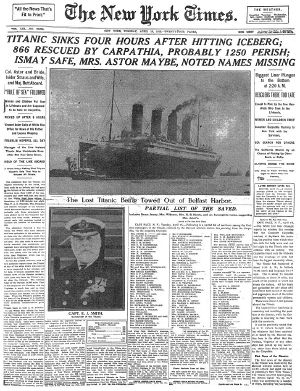

On the night of April 14, at 11:40 PM, The Titanic struck an iceberg. Titanic sank, with great loss of life, at 2:20 AM, on April 15, 1912. The United States Senate investigation reported that 1,517 people perished in the accident, while the British investigation has the number at 1,490.[3] Regardless, the disaster ranks as one of the worst peacetime maritime disasters in history, and is by far the best known. The media frenzy about the Titanic's famous victims, the legends about what happened on board the ship, the resulting changes to maritime law, Walter Lord's 1955 non-fiction account A Night to Remember, the discovery of the wreck in 1985 by a team led by Robert Ballard and Jean-Louis Michel, and the box office success of the 1997 film Titanic (the highest-grossing film in history) have sustained the Titanic's fame.

Contributing factors

Speed

The conclusion of the British Inquiry into the sinking was “that the loss of the said ship was due to collision with an iceberg, brought about by the excessive speed at which the ship was being navigated."[4] At the time of the collision, it is thought that the Titanic was at her normal cruising speed of about 22 knots,[5] which was less than her top speed of around 24 knots. It was then common (but not universal) practice to maintain normal speed in areas where icebergs were expected.[6] It was assumed that any iceberg large enough to damage the ship would be seen in sufficient time to be avoided. After the sinking, the British Board of Trade introduced regulations instructing vessels to moderate their speed if they were expecting to encounter icebergs. It is often alleged that J. Bruce Ismay instructed or encouraged Captain Edward Smith to increase speed in order to make an early landfall, and is a common feature in popular representations of the disaster. As there is no evidence for this having happened, many disputed the claim.[7]

Lifeboats

The Titanic did not carry sufficient lifeboats for all of her passengers and crew. The law at that time stipulated that a minimum of 16 lifeboats and enough places for 962 occupants were required for a ship that weighed more than 10,000 tons. This law was issued in 1894, when the largest emigrant steamer was the Lucania, of 12,952 tons. It had not been updated for 18 years, and ships had increased rapidly in size. Thus, the Titanic was only legally required to carry enough lifeboats for 962 occupants (the ship had room for 3,547 passengers). The White Star Line exceeded the regulations by including four collapsible lifeboats, bringing total lifeboat capacity to 1,178. [8]

In the busy North Atlantic sea lanes, it was expected that in the event of a serious accident, help from other vessels would be quickly obtained and that the lifeboats would be used to ferry passengers and crew from the stricken vessel to her rescuers. Full provision of lifeboats was not considered necessary for this. During the design of the ship, it was anticipated that the British Board of Trade might require an increase in the number of lifeboats at some future date. Therefore, lifeboat davits capable of handling up to four boats per pair of davits were designed by Alexander Carlisle and installed to give a total potential capacity of 64 boats.[9] The additional boats were never fitted. It is often alleged that J. Bruce Ismay, the president of White Star, vetoed the installation of these additional boats to maximise the passenger promenade area on the boat deck. Harold Sanderson, Vice President of International Mercantile Marine denied this allegation during the British Inquiry.[10]

The lack of lifeboats was not the only cause of the tragic loss of lives. After the collision with the iceberg, one hour was taken to evaluate the damage, recognize what was going to happen, inform first-class passengers, and lower the first lifeboat. Afterwards, the crew worked quite efficiently, taking a total of 80 minutes to lower all 16 lifeboats. The crew was divided into two teams, one on each side of the ship, and an average of 10 minutes of work was necessary for a team to fill a lifeboat with passengers and lower it.[citation needed]

Yet another factor in the high death toll that related to the lifeboats was the reluctance of the passengers to board them. They were, after all, on a ship deemed to be "unsinkable." Because of this, some lifeboats were launched with far less than capacity, the most notable being Lifeboat #1, with a capacity of 40, launched with only 12 people aboard. Included in the first launched were lifeboats 6, 7, and 8, each of which were equipped to hold 65 but evacuated the ship with only 28 on board each boat. [11]

The excessive number of casualties has also been blamed[citation needed] on the "women and children first" policy for places on the lifeboats. Although the lifeboats had a total capacity of 1,178 - enough for 53% of the 2,224 persons on board - the boats launched only had a capacity of 1,084, and, altogether only 712 people were actually saved - 32% of those originally on board. This is a result when the 1,084-person capacity of the lifeboats actually launched had sufficient room to include all of the 534 women and children on board, plus an additional 550 men (of which there were 1,690 on board). It has been suggested[citation needed] based on these figures that allowing one man on board for each woman or child from the start would not only have increased the number of women and children saved but also had the added benefit of saving more lives in total. As it was, the many desperate men had to be held off at gunpoint from boarding the lifeboats, adding to the chaos of the scene, and there were many more casualties - of women, children and men - than otherwise.[12]

Manuevering

There is speculation that if Titanic had not altered its course but reversed its engines and had run head-on into the iceberg, the damage would only have affected the first or first two compartments. The ship had three propellers; reciprocating steam engines drove the outboard propellers, and a steam turbine drove the centre propeller [citation needed]. The reciprocating engines were reversible, but the turbine was not; however, reversing the rotation was not instantaneous and may not have been possible in the short time between sighting and impact [citation needed].

The liner SS Arizona had such a head-on collision with an iceberg in 1879 and, although badly damaged, managed to make it to St John's, Newfoundland for repairs. Some dispute that Titanic would have survived such a collision, however, since Titanic's speed was higher than Arizona's, her hull much larger and mass much greater, and the violence of the collision might still have compromised her structural integrity. [citation needed]

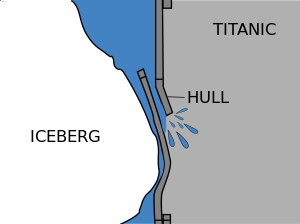

Faults in construction or substandard materials

Template:Cleanup

Soon after the discovery of the wreck site of the Titanic, scientists, naval architects, and marine engineers began questioning how faulty design features and poorly manufactured materials may have played a role in her sinking. Numerous ideas have been suggested, including poorly designed safety doors, brittle steel and the variable quality of rivets that attached the hull plating together. [13] However, it is more likely that a combination of these issues and other circumstances were major contributing factors to the sinking. It is possible that if the watertight bulkheads had completely sealed the ship's compartments, the ship would have stayed afloat (these only went 3 m above the waterline). [citation needed]

Titanic's hull plates were held together by rivets, metal pins which provide a means of clamping structural components together. In 1912, welding technology was still in its infancy, and shipbuilders would continue to utilize riveting almost exclusively for the next 20 years. Critical metallurgical issues have been identified with Titanic rivets salvaged from the wreck site. [14], [15] While most riveted ships of the era managed to stay afloat following collisions, the wrought iron rivets used in Titanic had significant flaws in strength and structure which would not have been detected with the inspection techniques of the early 20th century. Modern day forensic metallurgists suggest that the rivets of the Titanic were of substandard quality, resulting in weak points that lead to structural failure during the collision. [16]

Long-term implications

The sinking of the RMS Titanic was a factor that influenced later maritime practices, ship design, and the seafaring culture. Changes included the establishment of the International Ice Patrol, a requirement for 24-hour radio watchkeeping on foreign-going passenger ships, and new regulations related to lifeboats.[citation needed]

International Ice Patrol

The Titanic disaster led to the convening of the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) in London, on 12 November 1913. On 30 January 1914, a treaty was signed by the conference that resulted in the formation and international funding of the International Ice Patrol, an agency of the United States Coast Guard that to the present day monitors and reports on the location of North Atlantic Ocean icebergs that could pose a threat to transatlantic sea lane traffic. It was also agreed in the new regulations that all passenger vessels would have sufficient lifeboats for everyone on board, that appropriate safety drills would be conducted, and that radio communications on passenger ships would be operated 24 hours a day along with a secondary power supply, so as not to miss distress calls. In addition, it was agreed that the firing of red rockets from a ship must be interpreted as a distress signal (red rockets launched from the Titanic prior to sinking were mistaken by nearby vessels as celebratory fireworks, delaying rescue). This treaty was scheduled to go into effect on 1 July 1915 but was upstaged by World War I.

Ship design changes

The sinking of Titanic changed the way passenger ships were designed. Many existing ships, such as the Olympic, were refitted for increased safety. Besides increasing the number of lifeboats on board, improvements included reinforcing the hull and increasing the height of the watertight bulkheads. The bulkheads on Titanic extended 10 feet (3 m) above the waterline; after Titanic sank, the bulkheads on other ships were extended higher to make compartments fully watertight. While Titanic had a double bottom, she did not have a double hull; after her sinking, new ships were designed with double hulls; also, the double bottoms of other ships (including the Olympic) were extended up the sides of their hulls, above their waterlines, to give them double hulls. [citation needed]

Alternative theories and myths

As with many famous events, many alternative theories about the sinking of Titanic have appeared over the years. Theories that it was not an iceberg that sank the ship or that a curse caused the disaster have been popular reading in newspapers and books. Most of these theories have been debunked by Titanic experts, claiming that the evidence on which these theories were based was inaccurate or incomplete.

Use of SOS

The sinking of the Titanic was not the first time the internationally recognised Morse code distress signal "SOS" was used. The SOS signal was first proposed at the International Conference on Wireless Communication at Sea in Berlin in 1906. It was ratified by the international community in 1908 and had been in widespread use since then. The SOS signal was, however, rarely used by British wireless operators, who preferred the older CQD code. First Wireless Operator Jack Phillips began transmitting CQD until Second Wireless Operator Harold Bride suggested, half-jokingly, "Send SOS; it's the new call, and this may be your last chance to send it." Phillips, who was to perish in the disaster, then began to intersperse SOS with the traditional CQD call.

Novel's foreshadowing

In 1898, Morgan Robertson published a book called Futility in which a ship called Titan sinks after colliding with an iceberg[17]. There are striking similarities between the 'Titan' and the Titanic' disaster such as both ships sank in the North Atlantic Ocean during the month of April, both ships did not have enough lifeboats and were allegedly traveling at an excessive speed, and both were considered the largest ship of their time.[18]

Other myths

A similar legend states that the Titanic was given hull number 390904 (which, when seen in a mirror or written using mirror writing, looks like "NO POPE"). This is a myth.[19] Titanic's yard number was 401; Olympic's was 400. Another myth states that Titanic was carrying a cursed Egyptian mummy, often named Princess of Amen-Ra. The mummy, nicknamed Shipwrecker after changing hands several times and causing many terrible things to happen to each of its owners, exacts its final revenge by sinking the famous ship. There was no mummy on board, only a coffin lid.[20] Another myth says that the bottle of champagne used in christening Titanic did not break on the first try, which in sea lore is said to be bad luck for a ship. In fact, Titanic was not christened on launching, as it was White Star Line's custom not to do so. [21]

Rediscovery

{{#invoke:Message box|ambox}}

For 70 years after the disaster, it was widely believed that the Titanic had sunk intact. Although there were several passengers who insisted that the ship had broken in two as it sank (including Jack Thayer, who even had another passenger draw a set of sketches depicting the sinking for him [22]), the inquiries believed the statements of the ship's officers and first-class passengers that it had sunk in one piece.

In 1985, when the wreck was discovered by Jean-Louis Michel of IFREMER, Robert Ballard and his crew, they found that the ship broke in two as it sank. It was theorised that as the Titanic sank, the stern rose out of the water. It supposedly rose so high that the unsupported weight caused the ship to break into two pieces, the split starting at the upper deck. This became the commonly accepted theory.

In 2005, new evidence suggested that in addition to the expected side damage, the ship also had sustained damage to the bottom of the hull (keel). This new evidence seemed to support a less popular theory that the crack that split the Titanic in two started at the keel plates. This proposition is supported by Jack Thayer's sketches.

The idea of finding the wreck of Titanic and even raising the ship from the ocean floor had been perpetuated since shortly after the ship sank. No attempts even to locate the ship were successful until 1 September 1985, when a joint French-American expedition[23], led by Jean-Louis Michel of IFREMER and Dr Robert Ballard of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, sailing on the Research Vessel Knorr, discovered the wreck using the video camera sled Argo. It was found at a depth of 12,536 feet (3,821 m), south-east of Newfoundland at {{#invoke:Coordinates|coord}}{{#coordinates:41|43|32|N|49|56|49|W|type:landmark_scale:30000000 | |name= }}[24], 13 nautical miles (24 km) from where Titanic was originally thought to rest.

The most notable discovery the team made was that the ship had broken in two, the stern section lying 1,970 feet (600 m) from the bow section and both facing in opposite directions. There had been conflicting witness accounts of whether the ship broke apart on the surface or not, and both the American and British inquiries found that the ship sank intact. Up until the discovery of the wreck, it was generally assumed the ship did not break apart. In 2005, a theory was presented that a portion of Titanic's bottom broke off right before the ship broke in two.[25] The theory was conceived after an expedition sponsored by The History Channel examined the three hull pieces.[26]

The bow section had embedded itself more than 60 feet (18 m) into the silt on the ocean floor. Although parts of the hull had buckled, the bow was mostly intact, as the water inside had equalised with the increasing water pressure. The stern section was in much worse condition. As the stern section sank, water pushed out the air inside tearing apart the hull and decks. The speed at which the stern hit the ocean floor caused even more damage. Surrounding the wreck is a large debris field, with pieces of the ship (including a large amount of coal), furniture, dinnerware and personal items scattered over one square mile (2.6 km²). Softer materials, like wood and carpet, were devoured by undersea organisms, as were human remains.

Later exploration of the vessel's lower decks, as chronicled in the book Ghosts of the Titanic by Charles Pellegrino, showed that much of the wood from Titanic's staterooms was still intact. A new theory has been put forth that much of the wood from the upper decks was not devoured by undersea organisms but rather broke free of its fixings and floated away. This is supported by some eyewitness testimony from the survivors.

In April 1996, RMS Titanic Inc., which holds salvage rights to the Titanic organized a cruise from Boston, Massachusetts to the site of Titanic's sinking. The company intended to bring to the ocean's surface a small section of Titanic's hull among other artifacts. Among those on board the cruise ship was 99-year old Titanic survivor Edith Eileen Haisman. Ms. Haisman was 15 years old when the ship sank and had vivid memories from that night.[27]

Condition of the wreck

Many scientists, including Robert Ballard, are concerned that visits by tourists in submersibles and the recovery of artefacts are hastening the decay of the wreck. Underwater microbes have been eating away at Titanic's iron since the ship sank, but because of the extra damage visitors have caused, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that "the hull and structure of the ship may collapse to the ocean floor within the next 50 years." Several scientists and conservationists have also complained about the removal of the crow's nest on the mast by a French expedition.

Ballard's book, Return to Titanic, published by the National Geographic Society, includes photographs showing the deterioration of the promenade deck and damage caused by submersibles landing on the ship. The mast has almost completely deteriorated, and repeated accusations were made that it had been stripped of its bell and brass light by salvagers. Ballard's own original discovery images however, clearly showing that the bell was never actually on the mast - it was recovered from the sea floor. The French submersible Nautile allegedly is responsible for crashing into the crow's nest and causing it to fall from the mast. Even the memorial plaque left by Ballard on his second trip to the wreck was alleged to have been removed; Ballard replaced the plaque in 2004. Recent expeditions, notably by James Cameron, have been diving on the wreck to learn more about the site and explore previously unexplored parts of the ship before Titanic decays completely.

Ownership and litigation

Ballard and his crew did not bring up any artefacts from the wreck. Upon discovery in 1985, a legal debate began over ownership of the wreck and the valuable artefacts inside. On 7 June 1994, RMS Titanic Inc. was awarded ownership and salvaging rights of the wreck[28] by the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. (See Admiralty law)[29] RMS Titanic Inc., a subsidiary of Premier Exhibitions Inc., and its predecessors have conducted seven expeditions to the wreck between 1987 and 2004 and salvaged over 5,500 objects. The biggest single recovered artefact was a 17-ton section of the hull, recovered in 1998.[30] Many of these artefacts are part of travelling museum exhibitions.

Beginning in 1987, a joint American-French expedition, which included the predecessor of RMS Titanic Inc., began salvage operations and, during 32 dives, recovered approximately 1,800 artefacts which were taken to France for conservation and restoration. In 1993, a French administrator in the Office of Maritime Affairs of the Ministry of Equipment, Transportation, and Tourism awarded RMS Titanic Inc's predecessor title to the artefacts recovered in 1987.

In a motion filed on 12 February 2004 RMS Titanic Inc. requested that the District Court enter an order awarding it "title to all the artefacts (including portions of the hull) which are the subject of this action pursuant to the Law of Finds" or, in the alternative, a salvage award in the amount of $225 million. RMS Titanic Inc. excluded from its motion any claim for an award of title to the 1987 artefacts, but it did request that the district court declare that, based on the French administrative action, "the artefacts raised during the 1987 expedition are independently owned by RMST." Following a hearing, the district court entered an order dated 2 July 2004, in which it refused to grant comity and recognize the 1993 decision of the French administrator, and rejected RMS Titanic Inc's claim that it should be awarded title to the artefacts recovered since 1993 under the Maritime Law of Finds.

RMS Titanic Inc. appealed to the United States Court of Appeals. In its decision of 31 January 2006[31] the court recognised "explicitly the appropriateness of applying maritime salvage law to historic wrecks such as that of Titanic" and denied the application of the Maritime Law of Finds. The court also ruled that the district court lacked jurisdiction over the "1987 artefacts," and therefore vacated that part of the court's 2 July 2004 order. In other words, according to this decision, RMS Titanic Inc. has ownership title to the artefacts awarded in the French decision (valued $16.5 million earlier) and continues to be salvor-in-possession of Titanic wreck. The Court of Appeals remanded the case to the District Court to determine the salvage award ($225 million requested by RMS Titanic Inc.).[32]

Popular culture

The sinking of Titanic has been the basis for many novels describing fictionalised events on board the ship. Many reference books about the disaster have also been written since Titanic sank, the first of these appearing within months of the sinking. Several films and TV movies were produced, the first being In Nacht und Eis as early as 1912. The 1997 film Titanic, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet was a critical and commercial hit, winning eleven Academy Awards and holding the record for the highest box office returns of all time. A Broadway musical, Titanic opened in New York in 1998 and won the Tony Award for Best Musical, among others. All of the characters are based on actual Titanic passengers and crew. The musical and film The Unsinkable Molly Brown features the famous Titanic survivor as well.

Recent survivors' deaths

- Barbara Dainton (née West) (May 24, 1911 – October 16, 2007)

- Lillian Asplund (October 21, 1906 – May 6, 2006)

- Winnifred Vera van Tongerloo (née Quick) (January 23, 1904 – July 6, 2002)

- Michel Marcel Navratil (June 12, 1908 – April 18, 2001)

- Eleanor Ileen Shuman (née Johnson) (August 23, 1910 – March 9, 1998)

- Louise Laroche (July 2, 1910 – January 28, 1998)

- Edith Eileen Haisman (née Brown) (October 27, 1896 – January 20, 1997)

- Eva Miriam Hart (January 31, 1905 – February 14, 1996)

- Beatrice Irene Sandström (August 9, 1910 – September 3, 1995)

- Ruth Elizabeth Becker (October 28, 1899 – July 6, 1990)

100th anniversary

On 15 April 2012, the 100th anniversary of the sinking of Titanic is planned to be commemorated around the world. By that date the Titanic Quarter in Belfast is planned to have been completed. The area will be regenerated and a signature memorial project unveiled to celebrate Titanic and her links with Belfast, the city that built the ship.[33]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ [=http://www.historyonthenet.com/Titanic/unsinkable.htm Titanic - unsinkable] Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Titanic's Blueprints Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Report on the Loss of the S.S. Titanic Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ↑ Final Report of the British Board of Trade Inquiry

- ↑ British Inquiry - Testimony of JG Boxhall -Fourth Officer - ss "Titanic," Q15645

- ↑ British Inquiry – Testimony of G Affeld, Marine Superintendent Red Star Line Q22583 & Q25615/16

- ↑ Paul Louden-Brown "The White Star Line; An Illustrated History 1869-1934"

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Testimony of Alexander Carlisle at British Inquiry

- ↑ Testimony of Harold Sanderson at British Inquiry - Question #19398

- ↑ Robin Gardener & Dan van der Vat, The Riddle of the Titanic (London: Orion 1995) p136

- ↑ Women and children first.

- ↑ Garzke, William H., Jr., David K. Brown, Paul K. Matthias, Roy Cullimore, David Wood, David Livingstone, H.P. Leighly, Jr., Timothy Foecke, and Arthur Sandiford. Titanic, The Anatomy of a Disaster. Proceedings of the 1997 Annual Meeting of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers, SNAME, Jersey City, New Jersey.

- ↑ Tim Foecke, Metallurgy of the RMS Titanic, National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST-IR 6118, February 4, 1998

- ↑ J. Hooper McCarty, PhD Thesis, The Johns Hopkins University, 2003

- ↑ Jennifer Hooper McCarty and Tim Foecke, What Really Sank the Titanic: New Forensic Discoveries, February 2008, ISBN 0806528958

- ↑ http://www.lux-aeterna.co.nz/Titan.htm

- ↑ http://www.lux-aeterna.co.nz/Titan.htm

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ Titanic: Demographics of the Passengers.

- ↑ Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution: Discovery of the Titanic

- ↑ Titanic Wreck Location, Titanic-Titanic.com

- ↑ "Scientists ponder Titanic discoveries", CNN, December 5, 2005.

- ↑ Lindsay, Jay, "Scientists unveil new discoveries from Titanic wreck", Associated Press, December 5, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/item/5253/

- ↑ Comprehensive resume of ownership questions

- ↑ Corporate Profile. RMS Titanic, Inc.. Retrieved February 1, 2006.

- ↑ Expeditions. RMS Titanic, Inc.. Retrieved February 1, 2006.

- ↑

PDF

PDF

- ↑ Commented excerpts of the Court of Appeals decision.

- ↑ [5]

- Brander, Roy. The RMS Titanic and its Times: When Accountants Ruled the Waves. Elias P. Kline Memorial Lecture, October 1998 http://www.cuug.ab.ca/~branderr/risk_essay/Kline_lecture.html

- Butler, Daniel Allen. Unsinkable: The Full Story of RMS Titanic. Stackpole Books, 1998, 292 pages

- Collins, L. M. The Sinking of the Titanic: The Mystery Solved Souvenir Press, 2003 ISBN 0-285-63711-8

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. Titanic: Triumph and Tragedy (2nd ed.). W.W. Norton & Company, 1995 ISBN 0-393-03697-9

- Eaton, John P. and Haas, Charles A. Falling Star: The Misadventures of White Star Line Ships, c. 1990 W.W. Norton & Company, 1990 ISBN 0-3930-2873-7

- Gardener, R & van der Vat, D The Riddle of the Titanic Orion 1995

- Kentley, Eric. Discover the Titanic Ed. Claire Bampton and Sue Leonard. 1st ed. New York: DK, Inc., 1997. 22. ISBN 0-7894-2020-1

- Lord, Walter (1997). A Night to Remember Introduction by Nathaniel Philbrick. Bantam. ISBN 0-553-27827-4

- Lynch, Donald and Marschall, Ken. Titanic: An Illustrated History Hyperion, 1995 ISBN 1-56282-918-1

- O'Donnell, E. E. Father Browne's Titanic Album Wolfhound Press, 1997. ISBN 0-86327-758-6

- Quinn, Paul J. Titanic at Two A.M.: An Illustrated Narrative with Survivor Accounts. Fantail, 1997 ISBN 0-9655209-3-5

- Wade, Wyn Craig, The Titanic: End of a Dream Penguin Books, 1986 ISBN 0-14-016691-2

- US Coast Guard. International Ice Patrol History. Page viewed May 2006. http://www.uscg.mil/LANTAREA/IIP/General/history.shtml

- Beveridge, Bruce. Olympic & Titanic: The Truth Behind the Conspiracy

- Chirnside, Mark. The Olympic-Class Ships

- Layton, J. Kent. Atlantic Liners: A Trio of Trios

- Ballard, Robert B. Lost Liners

PDF

PDF- Pellegrino, Charles R. Her Name, Titanic Avon, 1990 ISBN 0-380-70892-2

- Hooper McCarty, Jennifer and Foecke, Tim. What Really Sank the Titanic: New Forensic Discoveries. Kensington Books, 2008, ISBN 0806528958. http://www.csititanic.com

External links

- Encyclopedia Titanica, an invaluable source of information concerning the sinking of the Titanic, including over 10000 biographies and articles.

- Titanic Historical Society

- Titanic Inquiry Project Complete transcripts of both the US Senate and British Board of Trade inquiries into the disaster, along with their final reports.

- Thomas Andrews, Shipbuilder A biography of the Titanic's designer

- PBS Online - Lost Liners

- Ocean Planet:How Deep Can they Go?

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Olympic |

World's largest passenger ship 1911 – 1912 |

Succeeded by: Olympic |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.