Pliocene

The Pliocene epoch (spelled Pleiocene in some older texts) is the period in the geologic timescale that extends from 5.332 million to 1.806 million years before present. The Pliocene is the second epoch of the Neogene period of the Cenozoic era. The Pliocene follows the Miocene epoch and is followed by the Pleistocene epoch. it provided the foundation for the modern era.

The Pliocene was named by Sir Charles Lyell. The name comes from the Greek words pleion (more) and ceno (new), meaning, roughly, "continuation of the recent," and refers to the essentially modern marine mollusk faunas.

As with other older geologic periods, the geological strata that define the start and end are well identified, but the exact dates of the start and end of the epoch are slightly uncertain. The boundaries defining the onset of the Pliocene are not set at an easily identified worldwide event, but rather at regional boundaries between the warmer Miocene and the relatively cooler Pliocene. The upper boundary was intended to be set at the start of the Pleistocene glaciations but is now considered to be set too late. Many geologists find the broader divisions into Paleogene and Neogene more useful.

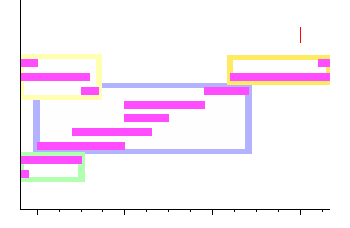

| Tertiary sub-era | Quaternary sub-era | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neogene period | ||||

| Miocene | Pliocene | Pleistocene | Holocene | |

| Aquitanian | Burdigalian | Zanclean | Early | |

| Langhian | Serravallian | Piacenzian | Middle | |

| Tortonian | Messinian | Gelasian | Late | |

Subdivisions

The Pliocene faunal stages (divisions according to fossils), from youngest to oldest, according to International Commission on Stratigraphy classification are:

| Gelasian | (2.588–1.806 mya (million years ago)) |

| Piacenzian | (3.600–2.588 mya) |

| Zanclean | (5.332–3.600 mya) |

The first two stages make up the Early; the last is the Late Pliocene.

For most of North America, a different system (NALMA) is often used, which overlaps epoch boundaries:

| Blancan | (4.75–1.806 mya) |

| Hemphillian | (9–4.75 mya); includes most of the Late Miocene |

Other classification systems are used for California, Australia, Japan, and New Zealand.

Paleogeography and climate

During the Pliocene, continents continued to drift toward their present positions, moving from as far as 250 km from their present locations to only 70 km from their current locations.

Africa's collision with Europe formed the Mediterranean Sea, cutting off the remnants of the Tethys Ocean. Sea level changes exposed the land-bridge between Alaska and Asia.

South America became linked to North America through the Isthmus of Panama during the Pliocene, bringing a nearly complete end to South America's distinctive marsupial faunas. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama about 3.5 million years ago cut off the final remnant of what was once essentially a circum-equatorial current that had existed since the Cretaceous and the early Cenozoic. The Isthmus formation had major consequences on global temperatures, since warm equatorial ocean currents were cut off and an Atlantic cooling cycle began, with cold Arctic and Antarctic waters dropping temperatures in the now-isolated Atlantic Ocean.

Although oceans continued to be relatively warm during the Pliocene, they continued cooling. The Arctic ice cap formed, drying the climate and increasing cool shallow currents in the North Atlantic. The formation of the Arctic ice cap around 3 mya is signaled by an abrupt shift in oxygen isotope ratios and ice-rafted cobbles in the North Atlantic and North Pacific Ocean beds (Van Andel 1994).

During the Pliocene, climates became cooler and drier, and seasonal, similar to modern climates. Antarctica became ice-bound, entirely covered with year-round glaciation, near or before the start of the Pliocene. Mid-latitude glaciation was probably underway before the end of the epoch.

Pliocene marine rocks are well exposed in the Mediterranean, India, and China. Elsewhere, they are exposed largely near shores.

Flora

The change to a cooler, dry, seasonal climate had considerable impacts on Pliocene vegetation, reducing tropical species world-wide. Deciduous forests proliferated, coniferous forests and tundra covered much of the north, and grasslands spread on all continents (except Antarctica). Tropical forests were limited to a tight band around the equator, and in addition to dry savannas, deserts appeared in Asia and Africa.

Fauna

Both marine and continental faunas were essentially modern, although continental faunas were a bit more primitive than today. The first recognizable hominins, the australopithecines, appeared in the Pliocene.

The land mass collisions meant great migration and mixing of previously isolated species. Herbivores got bigger, as did specialized predators.

The Pliocene-Pleistocene boundary had a considerable number of marine extinctions. A supernova is considered a plausible but unproven candidate for the marine extinctions, as it may have caused a significant breakdown of the ozone layer. In 2002, astronomers discovered that roughly 2 million years ago, around the end of the Pliocene epoch, a group of bright O and B stars, called the Scorpius-Centaurus OB association, passed within 150 light-years of Earth and that one or more supernovas may have occurred in this group at that time. Such a close explosion could have damaged the Earth's ozone layer. At its peak, a supernova of this size could produce that same amount of absolute magnitude as an entire galaxy of 200 billion stars (Comins and Kaufmann 2005).

Birds. The predatory phorusrhacids were rare during the Pliocene; among the last was Titanis, a large phorusrhacid that rivaled mammals as top predators. Its distinct feature was it claws, which were adapted for grasping prey, such as Hipparion. Both modern birds and extinct birds were also present during this time.

Reptiles. Alligators and crocodiles died out in Europe as the climate cooled. Venomous snake genera continued to increase as more rodents and birds evolved.

Mammals. In North America, rodents, large mastodonts and gomphotheres, and opossums continued successfully, while hoofed animals (ungulates) declined, with camel, deer, and horse all seeing populations recede. In North America, Rhinoceroses, tapirs, and chalicotheres went extinct. Carnivores, including the weasel family, diversified, and dogs and fast-running hunting bears did well. Ground sloths, huge glyptodonts, and armadillos came north with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama.

In Eurasia, rodents did well, while primate distribution declined. Elephants, gomphotheres, and stegodonts were successful in Asia, and hyraxes migrated north from Africa. Horse diversity declined, while tapirs and rhinos did fairly well. Cattle and antelopes were successful, and some camel species crossed into Asia from North America. Hyenas and early saber-toothed cats appeared, joining other predators including dogs, bears, and weasels.

|

Africa was dominated by hoofed mammals, and primates continued their evolution, with australopithecines (some of the first hominids) appearing in the late Pliocene. Rodents were successful, and elephant populations increased. Cattle and antelopes continued diversification, overtaking pigs in number of species. Early giraffes appeared, and camels migrated via Asia from North America. Horses and modern rhinos came onto the scene. Bears, dogs, and weasels (originally from North America) joined cats, hyenas, and civets as the African predators, forcing hyenas to adapt as specialized scavengers.

South America was invaded by North American species for the first time since the Cretaceous, with North American rodents and primates mixing with southern forms. Litopterns and the notoungulates, South American natives, did well. Small weasel-like carnivorous mustelids and coatis migrated from the north. Grazing glyptodonts, browsing giant ground sloths, and smaller armadillos did well.

The marsupials remained the dominant Australian mammals, with herbivore forms including wombats and kangaroos, and the huge diprotodonts. Carnivorous marsupials continued hunting in the Pliocene, including dasyurids, the dog-like thylacine, and cat-like Thylacoleo. The first rodents arrived, while bats did well, as did ocean-going whales. The modern platypus, a monotreme, appeared.

The Pliocene seas were alive with sea cows, seals, and sea lions.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Comins, N. F. and W. J. Kaufmann. 2005. Discovering the Universe, 7th edition. New York: Susan Finnemore Brennan. ISBN 0-7167-7584-0

- Ogg, J. 2004. Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's). Retrieved April 30, 2006.

- Van Andel, T. H. 1994. New Views on an Old Planet: A History of Global Change, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521447550

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.