Difference between revisions of "Nazi human experimentation" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 75: | Line 75: | ||

[[Image:Dachau cold water immersion.jpg|right|thumb|A cold water immersion experiment at Dachau concentration camp presided over by Ernst Holzlöhner (left) and Sigmund Rascher (right). The subject is wearing an experimental Luftwaffe garment. In 1941, the ''Luftwaffe'' conducted experiments with the intent of discovering means to prevent and treat [[hypothermia]]. There were 360 to 400 experiments and 280 to 300 victims indicating some victims suffered more than one experiment (Berger 1990).]] | [[Image:Dachau cold water immersion.jpg|right|thumb|A cold water immersion experiment at Dachau concentration camp presided over by Ernst Holzlöhner (left) and Sigmund Rascher (right). The subject is wearing an experimental Luftwaffe garment. In 1941, the ''Luftwaffe'' conducted experiments with the intent of discovering means to prevent and treat [[hypothermia]]. There were 360 to 400 experiments and 280 to 300 victims indicating some victims suffered more than one experiment (Berger 1990).]] | ||

| − | Beginning in August 1942, at the Dachau camp, prisoners were forced to sit in tanks of freezing water for up to three hours. After subjects were frozen, they then underwent different methods for rewarming. Many subjects died in this process (Jewish Virtual Library) | + | Beginning in August 1942, at the Dachau camp, prisoners were forced to sit in tanks of freezing water for up to three hours. After subjects were frozen, they then underwent different methods for rewarming. Many subjects died in this process (Jewish Virtual Library). |

Another study placed prisoners naked in the open air for several hours with temperatures as low as −6 °C (21 °F). Besides studying the physical effects of cold exposure, the experimenters also assessed different methods of rewarming survivors (Bogod 2004). "One assistant later testified that some victims were thrown into boiling water for rewarming" (Berger 1990). | Another study placed prisoners naked in the open air for several hours with temperatures as low as −6 °C (21 °F). Besides studying the physical effects of cold exposure, the experimenters also assessed different methods of rewarming survivors (Bogod 2004). "One assistant later testified that some victims were thrown into boiling water for rewarming" (Berger 1990). | ||

| − | The freezing/hypothermia experiments were conducted for the Nazi high command to simulate the conditions the armies suffered on the Eastern Front, as the German forces were ill-prepared for the cold weather they encountered. Many experiments were conducted on captured Russian troops; the Nazis wondered whether their genetics gave them superior resistance to cold. The principal locales were Dachau concentration camp and Auschwitz. Sigmund Rascher, an SS doctor based at Dachau, reported directly to[Reichsführer-SS [[Heinrich Himmler]] and publicized the results of his freezing experiments at the 1942 medical conference entitled "Medical Problems Arising from Sea and Winter" (Tyson 2000). In a letter from September 10, 1942, Rascher describes an experiment on intense cooling performed in Dachau where people were dressed in fighter pilot uniforms and submerged in freezing water. Rascher had some of the victims completely underwater and others only submerged up to the head (Jewish Virtual Library). | + | The freezing/hypothermia experiments were conducted for the Nazi high command to simulate the conditions the armies suffered on the Eastern Front, as the German forces were ill-prepared for the cold weather they encountered. Many experiments were conducted on captured Russian troops; the Nazis wondered whether their genetics gave them superior resistance to cold. The principal locales were Dachau concentration camp and Auschwitz. Sigmund Rascher, an SS doctor based at Dachau, reported directly to[Reichsführer-SS [[Heinrich Himmler]] and publicized the results of his freezing experiments at the 1942 medical conference entitled "Medical Problems Arising from Sea and Winter" (Tyson 2000). In a letter from September 10, 1942, Rascher describes an experiment on intense cooling performed in Dachau where people were dressed in fighter pilot uniforms and submerged in freezing water. Rascher had some of the victims completely underwater and others only submerged up to the head (Jewish Virtual Library). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{|class="wikitable" | {|class="wikitable" | ||

| − | |+"Exitus" (death) table compiled by | + | |+"Exitus" (death) table compiled by Sigmund Rascher (Distel 2005). |

|- | |- | ||

!Attempt no. | !Attempt no. | ||

| Line 272: | Line 266: | ||

* Steinbacher, Sybille. 2005. ''Auschwitz: A History''. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-0-06-082581-2. | * Steinbacher, Sybille. 2005. ''Auschwitz: A History''. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-0-06-082581-2. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * Tyson, Peter. 2000. [https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/holocaust/experiside.html Holocaust on trial: the experiments]. ''NOVA Online''. Retrieved October 7, 2021. | ||

* United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. n.d. [https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/doctors-trial/nuremberg-code Nuremberg Code]. [United States Holocaust Memorial Museum note]. Retrieved July 25, 2021. | * United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. n.d. [https://www.ushmm.org/information/exhibitions/online-exhibitions/special-focus/doctors-trial/nuremberg-code Nuremberg Code]. [United States Holocaust Memorial Museum note]. Retrieved July 25, 2021. | ||

Revision as of 19:21, 7 October 2021

Nazi human experimentation, in the context of this article, refers to the human subject research conducted by Nazi physicians, researchers, and their assistants on men, women, and children who did not volunteer or consent for procedures that were inhumane and often brutal. This includes the experiments conducted on prisoners in Nazi concentration camps in the early to mid 1940s, during World War II and the Holocaust. Typically, the experiments were conducted without anesthesia and resulted in death, trauma, disfigurement, or permanent disability, and as such are considered examples of medical torture.This article is limited to human subject research and does not include the non-research-based activities of Nazi physicians in the sterilization and genocide of those deemed undesirable by the State on the basis of ethnicity or disability.

The Nazi human experiments included such atrocities as amputation and removal of body parts without anesthesia, deliberate infection with disease, exposure to extreme cold or low pressure, sewing of twins together, injection of substances into eyes, infliction of chemical burns, forced dehydration, and administering of poisons. Along with the horrifying war crimes committed by Unit 731 (the biological and chemical warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army), the Nazi human experiments represented one of the notorious chapters in human subject research. After World War II, many of the Nazi physicians were tried in the particular Nuremberg Trial known as the Doctors' Trial. The Nuremberg Code is a set of fundamental ethical standards that were released as part of the judges' decision in August 1947.

Given the horrific nature of the experiments, one issue that remains is whether or not one can ethically justify the present-day use of the results of those experiments.

Historical overview

Nazi Germany or the Third Reich, officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945, was the state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a dictatorship. Under Hitler's rule, Germany quickly became a totalitarian state where nearly all aspects of life were controlled by the government. The term Third Reich, meaning "Third Realm" or "Third Empire", alluded to the Nazis' conceit that Nazi Germany was the successor to the earlier Holy Roman Empire (800–1806) and German Empire (1871–1918). The Third Reich, which Hitler and the Nazis referred to as the Thousand Year Reich, ended in May 1945 when the Allies defeated Germany, ending World War II in Europe.

Racism, Nazi eugenics, and antisemitism, were central ideological features of the regime. The Germanic peoples were considered by the Nazis to be the master race, the purest branch of the Aryan race. Discrimination and the persecution of Jews and Romani people began in earnest after the seizure of power. The first Nazi concentration camps were established in March 1933. Jews and others deemed undesirable or who opposed Hitler's rule were imprisoned, killed, or exiled. More than 1,000 concentration camps (including subcamps) were established during the history of Nazi Germany and around 1.65 million people were registered prisoners in the camps at one point. Around a million died during their imprisonment.

Prior to the advent of Nazism, there were informal and formal codes of ethics relative to German medical research. An example of the former were the German medical researchers who performed their experiments on themselves or on their own children prior to using others as subjects. An example of the latter was the Reich Circular on Human Experimentation of February 28, 1931, which included such regulations as the provision that "experimentation involving children or young persons under 18 years of age shall be prohibited if it in any ways endangers the child or young person" and "innovative therapy may be carried out only after the subject or his legal representative has unambiguously consented to the procedure in light of relevant information provided in advance" (Weindling 2011).

However, even with such codes many unethical medical experiments continued to be conducted in pre-Nazi Germany, including experimentation in orphanages and prisons and Hans Eppinger's "invasive research without consent on parties in public wards in Vienna in the 1930s" (Weindling 2011).

After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Jewish doctors began to be purged from hospitals, universities, and public health positions and in 1938 were delicensed.

The advent of Nazi Germany led to many German physicians and their associates advancing a "race-based program of public health and genocide," unethical medical experiments "to advance medical and racial science," and inflicting 'unparalleled medical atrocities" (Weindling 2011). Weindling (2011), in his summary of "The Nazi Medical Experiments," noted that "physicians and medical and biological researchers took a central role in the implementation of the Holocaust and exploited imprisonment, ghettoization, and killings as opportunities for research," demanded that "mental and physical disabilities be eradicated from the German/Aryan/Nordic race by compulsory sterilization, euthanasa, and segregation."

Inhumane medical experiments were conducted on large numbers of prisoners, including children, by Nazi Germany in its concentration camps in the early to mid 1940s, during World War II and the Holocaust. Chief target populations included Romani, Sinti, ethnic Poles, Soviet POWs, disabled Germans, and Jews from across Europe. In addition, physicians provided support for mass killings in the concentration camps by undertaking selections as to whom would be sent to the gas chambers. Nazi physicians and their assistants forced concentration camp prisoners into participating; they did not willingly volunteer and no consent was given for the procedures.

At Auschwitz and other camps, under the direction of Eduard Wirths, selected inmates were subjected to various experiments that were designed to help German military personnel in combat situations, develop new weapons, aid in the recovery of military personnel who had been injured, and to advance the Nazi racial ideology and eugenics (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 2006), including the twin experiments of Josef Mengele (Wachsmann 2015).

After World War II, a series of trials were held in Nuremberg, Germany for individuals being charged as war criminals. The best known of these is the one held for major war criminals before the International Military Tribunal (IMT). However, the physicians who engaged in the notorious human experimentation were also subject to a trial, known as the “Doctors’ Trial.” This was held before an American military tribunal (U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunal or NMT) under Control Council Law No. 10. The Doctors’ Trial involved twenty-three defendants, most of who were medical doctors and were being accused of criminal human experimentation. The trial began on December 9, 1946, and concluded on August 20, 1947.

One of the issues before the tribunal was what constituted acceptable medical experimentation involving human subjects. Some of the Nazi doctors argued that their experiments differed little from those conducted by American and German researchers in the past, and that there was no international law or even informal statements that differentiated illegal from legal human experimentation. For this reason, there was a need for the prosecution to demonstrate how the defendants' experiments had deviated from fundamental ethical principles that should govern research in civilized society. This led to the creation of the Nuremberg Code, which was issued as part of the verdict issued in August 1947.

After the Nuremberg Trials, unethical research with human subjects continued to be conducted. To some extent, many researchers assumed that the Nuremberg Code was specific to the Nazi trials and thus were not applied to human subject research in general. In addition, even in the Doctors' Trial, "remarkably none of the specific findings against Brandt and his codefendants mentioned the code. Thus the legal force of the document was not well established" and "failed to find a place in either the American or German national law codes" (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

However, the Nuremberg Code did find great relevance in being a source for many subsequent codes of ethics for human subject research. The standards enumerated in the Nuremberg Code ended up being "incorporated into most subsequent ethical codes—such as the Declaration of Helsinki—and in [United States] federal research regulations" (Amdur and Bankert 2022). As noted by Amdur and Bankert (2022):

The basic elements of the Nuremberg Code are the requirement for:

- voluntary and informed consent,

- a favorable risk/benefit analysis, and

- the right to withdraw without penalty

Experiments

The Harvard Law School Library's Nuremberg Trials Project has catalogued a wide varied of documents from the Nuremberg Trials. One document, labeled "Table of contents for prosecution document book 8, concerning medical experiments" includes titles of sections that document medical experiments revolving around food, seawater, epidemic jaundice, sulfanilamide, blood coagulation, and phlegmon (NMT Prosecution 1947a). Others include one titled "List of prosecution documents in Document Book 4, on malaria experiments" (NMT Prosecution 1947b) and one titled "List of documents in Document Book 2: High altitude experiments" (NMT Prosecution 1947c), as well as others dealing with poison gas experiments.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2006), in an article titled "Nazi Medical Experiments," classifies the medical experiments into three categories: (1) Experiments dealing with the survival of military personnel (such as high-altitude and freezing experiments on prisoners, and experiments related to drinking seawater); (2) Experiments to test drugs and treatments (such as bone-grafting, exposure to phosgene and mustard gas to test antidotes, exposure to various infections diseases, such as malaria and typhus, to test treatments, and testing with sulfanilamide drugs); and (3) experiments to test Nazi racial and ideological goals (Mengele's experiments on twins, sterilization experiments, testing of the ability of different groups to withstand contagious diseases, etc.)

The following present an overview of some of the Nazi human experiments conducted without subjects' consent or medical safeguards.

Experiments on twins

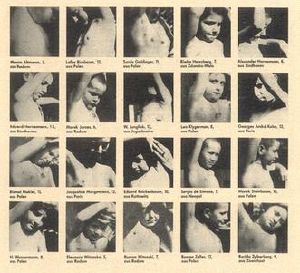

Experiments on twin children in concentration camps was under the central leadership of Josef Mengele. Josef Mengele (1911-1979) was a German Schutzstaffel (SS) officer and physician during World War II. He is mainly remembered for his actions at the Auschwitz concentration camp, where he performed deadly experiments on prisoners, and was a member of the team of doctors who selected victims to be killed in the gas chambers and was one of the doctors who administered the gas. Before the war, Mengele had received doctorates in anthropology and medicine, and began a career as a researcher. He joined the Nazi Party in 1937 and the SS in 1938. He was assigned as a battalion medical officer at the start of World War II, then transferred to the Nazi concentration camps service in early 1943 and assigned to Auschwitz, where he saw the opportunity to conduct genetic research on human subjects.

Mengele used Auschwitz as an opportunity to continue his anthropological studies and research into heredity, using inmates for human experimentation. His medical procedures showed no consideration for the victims' health, safety, or physical and emotional suffering (Kubica 1998). He was particularly interested in identical twins, people with heterochromia iridum (eyes of two different colors), those with dwarfism, and people with physical abnormalities (Kubica 1998).

From 1943 to 1944, Mengele performed experiments on nearly 1,500 sets of imprisoned twins at Auschwitz. The twin research was in part intended to prove the supremacy of heredity over environment and thus strengthen the Nazi premise of the genetic superiority of the Aryan race (Steinbacher 2005). Dr. Miklós Nyiszli (a Hungarian Jewish pathologist) and others reported that the twin studies may also have been motivated by an intention to increase the reproduction rate of the German race by improving the chances of racially desirable people having twins (Lifton 1986).

The experiments he performed on twins included unnecessary amputation of limbs, injecting dyes into their eyes to change their color, intentionally infecting one twin with typhus or some other disease, and transfusing the blood of one twin into the other. Many of the victims died while undergoing these procedures (Posner and Ware 1986) and those who survived the experiments were sometimes killed and their bodies dissected once Mengele had no further use for them (Lifton 1986). Nyiszli recalled one occasion on which Mengele personally killed fourteen twins in one night by injecting their hearts with chloroform (Lifton 1985). Often, one twin would be forced to undergo experimentation, while the other was kept as a control. If the experimentation reached the point of death, the second twin would be brought in to be killed at the same time. Doctors would then look at the effects of experimentation and compare both bodies, to allow comparative post-mortem reports to be produced for research purposes (Baron 2001; Lifton 1986). ). Witness Vera Alexander described how Mengele sewed two Romani twins together, back to back, in a crude attempt to create conjoined twins (Posner and Ware 1986); both children died of gangrene after several days of suffering (Mozes-Kor 1992).

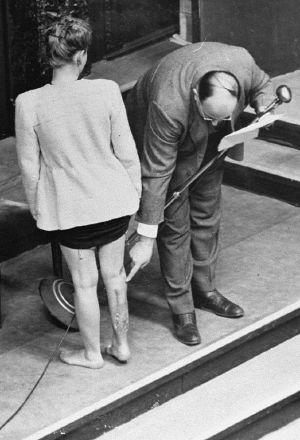

Bone, muscle, and nerve transplantation experiments

From about September 1942 to about December 1943, experiments were conducted at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, for the benefit of the German Armed Forces, to study bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration, and bone transplantation from one person to another. In these experiments, subjects had their bones, muscles and nerves removed without anesthesia. As a result of these operations, many victims suffered intense agony, mutilation, and permanent disability (Perpre and Cina 2010).

On August 12, 1946, a survivor named Jadwiga Kamińska gave a deposition about her time at Ravensbrück concentration camp and describes how she was operated on twice. Both operations involved one of her legs and although she never describes having any knowledge as to what exactly the procedure was, she explains that both times she was in extreme pain and developed a fever post surgery, but was given little to no aftercare. Kamińska describes being told that she had been operated on simply because she was a "young girl and a Polish patriot." She describes how her leg oozed pus for months after the operations (NMT Prosecution 1947d; University of Toronto).

Prisoners were also experimented on by having their bone marrow injected with bacteria to study the effectiveness of new drugs being developed for use in the battle fields. Those who survived remained permanently disfigured.

The following is a fragment from the 1958 Medical Statement issued Dr. Hanna Dworakowska (University of Toronto):

The criminal experiments consisted in the deliberate cutting out and infection of bones and muscles of the legs with virulent bacteria, the cutting out of nerves, the introducing into the tissues of virulent substances and the causing of artificial bone fractures. The experiments were conducted in conditions of utter disregard for the basic principles of asepsis. After all operation, the victim was left to her own fate and was in most cases exposed to harmful factors hampering self-defense by the organism. Some victims died in consequence of the operation itself or of the resulting complications and several were shot, while the survivors suffered major and extensive injuries to their organs of movement.

Head injury experiments

In mid-1942 in Baranowicze, occupied Poland, a notorious experiment was conducted in a small building behind the private home occupied by a known Nazi SD Security Service officer, in which "a young boy of eleven or twelve [was] strapped to a chair so he could not move. Above him was a mechanized hammer that every few seconds came down upon his head." The boy was driven insane from the torture (Small and Shayne 2009).

Freezing experiments

Beginning in August 1942, at the Dachau camp, prisoners were forced to sit in tanks of freezing water for up to three hours. After subjects were frozen, they then underwent different methods for rewarming. Many subjects died in this process (Jewish Virtual Library).

Another study placed prisoners naked in the open air for several hours with temperatures as low as −6 °C (21 °F). Besides studying the physical effects of cold exposure, the experimenters also assessed different methods of rewarming survivors (Bogod 2004). "One assistant later testified that some victims were thrown into boiling water for rewarming" (Berger 1990).

The freezing/hypothermia experiments were conducted for the Nazi high command to simulate the conditions the armies suffered on the Eastern Front, as the German forces were ill-prepared for the cold weather they encountered. Many experiments were conducted on captured Russian troops; the Nazis wondered whether their genetics gave them superior resistance to cold. The principal locales were Dachau concentration camp and Auschwitz. Sigmund Rascher, an SS doctor based at Dachau, reported directly to[Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and publicized the results of his freezing experiments at the 1942 medical conference entitled "Medical Problems Arising from Sea and Winter" (Tyson 2000). In a letter from September 10, 1942, Rascher describes an experiment on intense cooling performed in Dachau where people were dressed in fighter pilot uniforms and submerged in freezing water. Rascher had some of the victims completely underwater and others only submerged up to the head (Jewish Virtual Library).

| Attempt no. | Water temperature | Body temperature when removed from the water | Body temperature at death | Time in water | Time of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 5.2 °C (41.4 °F) | 27.7 °C (81.9 °F) | 27.7 °C (81.9 °F) | 66' | 66' |

| 13 | 6 °C (43 °F) | 29.2 °C (84.6 °F) | 29.2 °C (84.6 °F) | 80' | 87' |

| 14 | 4 °C (39 °F) | 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) | 27.5 °C (81.5 °F) | 95' | |

| 16 | 4 °C (39 °F) | 28.7 °C (83.7 °F) | 26 °C (79 °F) | 60' | 74' |

| 23 | 4.5 °C (40.1 °F) | 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) | 25.7 °C (78.3 °F) | 57' | 65' |

| 25 | 4.6 °C (40.3 °F) | 27.8 °C (82.0 °F) | 26.6 °C (79.9 °F) | 51' | 65' |

| 4.2 °C (39.6 °F) | 26.7 °C (80.1 °F) | 25.9 °C (78.6 °F) | 53' | 53' |

Malaria experiments

From about February 1942 to about April 1945, experiments were conducted at the Dachau concentration camp in order to investigate immunization for treatment of malaria. Healthy inmates were infected by mosquitoes or by injections of extracts of the mucous glands of female mosquitoes. After contracting the disease, the subjects were treated with various drugs to test their relative efficacy.[1] Over 1,200 people were used in these experiments and more than half died as a result.[2] Other test subjects were left with permanent disabilities.[3]

Immunization experiments

At the German concentration camps of Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Natzweiler, Buchenwald, and Neuengamme, scientists tested immunization compounds and serums for the prevention and treatment of contagious diseases, including malaria, typhus, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, yellow fever, and infectious hepatitis.[4][5]

Epidemic jaundice

From June 1943 until January 1945 at the concentration camps, Sachsenhausen and Natzweiler, experimentation with epidemic jaundice was conducted. The test subjects were injected with the disease in order to discover new inoculations for the condition. These tests were conducted for the benefit of the German Armed Forces. Most died in the experiments, whilst others survived, experiencing great pain and suffering.[6]

Mustard gas experiments

At various times between September 1939 and April 1945, many experiments were conducted at Sachsenhausen, Natzweiler, and other camps to investigate the most effective treatment of wounds caused by mustard gas. Test subjects were deliberately exposed to mustard gas and other vesicants (e.g. Lewisite) which inflicted severe chemical burns. The victims' wounds were then tested to find the most effective treatment for the mustard gas burns.[7]

Sulfonamide experiments

From about July 1942 to about September 1943, experiments to investigate the effectiveness of sulfonamide, a synthetic antimicrobial agent, were conducted at Ravensbrück.[8] Wounds inflicted on the subjects were infected with bacteria such as Streptococcus, Clostridium perfringens (a major causative agent in gas gangrene) and Clostridium tetani, the causative agent in tetanus.[9] Circulation of blood was interrupted by tying off blood vessels at both ends of the wound to create a condition similar to that of a battlefield wound. Researchers also aggravated the subjects' infection by forcing wood shavings and ground glass into their wounds. The infection was treated with sulfonamide and other drugs to determine their effectiveness.

Sea water experiments

From about July 1944 to about September 1944, experiments were conducted at the Dachau concentration camp to study various methods of making sea water drinkable. These victims were subject to deprivation of all food and only given the filtered sea water.[10] At one point, a group of roughly 90 Roma were deprived of food and given nothing but sea water to drink by Hans Eppinger, leaving them gravely injured.[11] They were so dehydrated that others observed them licking freshly mopped floors in an attempt to get drinkable water.[12]

A Holocaust survivor named Joseph Tschofenig wrote a statement on these seawater experiments at Dachau. Tschofenig explained how while working at the medical experimentation stations he gained insight into some of the experiments that were performed on prisoners, namely those in which they were forced to drink salt water. Tschofenig also described how victims of the experiments had trouble eating and would desperately seek out any source of water including old floor rags. Tschofenig was responsible for using the X-ray machine in the infirmary and describes how even though he had insight into what was going on he was powerless to stop it. He gives the example of a patient in the infirmary who was sent to the gas chambers by Sigmund Rascher simply because he witnessed one of the low-pressure experiments.[13]

Sterilization and fertility experiments

The Law for the Prevention of Genetically Defective Progeny was passed on 14 July 1933, which legalized the involuntary sterilization of persons with diseases claimed to be hereditary: weak-mindedness, schizophrenia, alcohol abuse, insanity, blindness, deafness, and physical deformities. The law was used to encourage growth of the Aryan race through the sterilization of persons who fell under the quota of being genetically defective.[14] 1% of citizens between the age of 17 to 24 had been sterilized within two years of the law passing.

Within four years, 300,000 patients had been sterilized.[15] From about March 1941 to about January 1945, sterilization experiments were conducted at Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and other places by Carl Clauberg.[7] The purpose of these experiments was to develop a method of sterilization which would be suitable for sterilizing millions of people with a minimum of time and effort. The targets for sterilization included Jewish and Roma populations.[16] These experiments were conducted by means of X-ray, surgery and various drugs. Thousands of victims were sterilized. Aside from its experimentation, the Nazi government sterilized around 400,000 people as part of its compulsory sterilization program.[17]

Carl Clauberg was the leading research developer in the search for cost effective and efficient means of mass sterilization. He was particularly interested in experimenting on women from age twenty to forty who had already given birth. Prior to any experiments, Clauberg x-rayed women to make sure that there was no obstruction to their ovaries. Next, over the course of three to five sessions, he injected the women's cervixes with the goal of blocking their fallopian tubes. The women who stood against him and his experiments or were deemed as unfit test subjects were sent to be killed in the gas chambers.[18]

Intravenous injections of solutions speculated to contain iodine and silver nitrate were successful, but had unwanted side effects such as vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, and cervical cancer.[19] Therefore, radiation treatment became the favored choice of sterilization. Specific amounts of exposure to radiation destroyed a person's ability to produce ova or sperm, sometimes administered through deception. Many suffered severe radiation burns.[20]

The Nazis also implemented x-ray radiation treatment in their search for mass sterilization. They gave the women abdomen x-rays, men received them on their genitalia, for abnormal periods of time in attempt to invoke infertility. After the experiment was complete, they surgically removed their reproductive organs, often without anesthesia, for further lab analysis.[18]

M.D. William E. Seidelman, a professor from the University of Toronto, in collaboration with Dr. Howard Israel of Columbia University, published a report on an investigation on the Medical experimentation performed in Austria under the Nazi Regime. In that report he mentions a Doctor Hermann Stieve, who used the war to experiment on live humans. Stieve specifically focused on the reproductive system of women. He would tell women their date of death in advance, and he would evaluate how their psychological distress would affect their menstruation cycles. After they were murdered, he would dissect and examine their reproductive organs. Some of the women were raped after they were told the date when they would be killed so that Stieve could study the path of sperm through their reproductive system.[21]

Experiments with poison

Somewhere between December 1943 and October 1944, experiments were conducted at Buchenwald to investigate the effect of various poisons. The poisons were secretly administered to experimental subjects in their food. The victims died as a result of the poison or were killed immediately in order to permit autopsies. In September 1944, experimental subjects were shot with poisonous bullets, suffered torture, and often died.[7]

Some male Jewish prisoners had poisonous substances scrubbed or injected into their skin, causing boils filled with black fluid to form. These experiments were heavily documented as well as photographed by the Nazis.[18]

Incendiary bomb experiments

From around November 1943 to around January 1944, experiments were conducted at Buchenwald to test the effect of various pharmaceutical preparations on phosphorus burns. These burns were inflicted on prisoners using phosphorus material extracted from incendiary bombs.[7]

High altitude experiments

In early 1942, prisoners at Dachau concentration camp were used by Sigmund Rascher in experiments to aid German pilots who had to eject at high altitudes. A low-pressure chamber containing these prisoners was used to simulate conditions at altitudes of up to 68,000 feet (21,000 m). It was rumored that Rascher performed vivisections on the brains of victims who survived the initial experiment.[22] Of the 200 subjects, 80 died outright, and the others were murdered.[11] In a letter from 5 April 1942 between Rascher and Heinrich Himmler, Rascher explains the results of a low-pressure experiment that was performed on people at Dachau Concentration camp in which the victim was suffocated while Rascher and another unnamed doctor took note of his reactions. The person was described as 37 years old and in good health before being murdered. Rascher described the victim's actions as he began to lose oxygen and timed the changes in behavior. The 37-year-old began to wiggle his head at four minutes, a minute later Rascher observed that he was suffering from cramps before falling unconscious. He describes how the victim then lay unconscious, breathing only three times per minute, until he stopped breathing 30 minutes after being deprived of oxygen. The victim then turned blue and began foaming at the mouth. An autopsy followed an hour later.[23]

In a letter from Himmler to Rascher on 13 April 1942, Himmler ordered Rascher to continue the high altitude experiments and to continue experimenting on prisoners condemned to death and to "determine whether these men could be recalled to life". If a victim could be successfully resuscitated, Himmler ordered that he be pardoned to "concentration camp for life".[24]

Blood coagulation experiments

Sigmund Rascher experimented with the effects of Polygal, a substance made from beet and apple pectin, which aided blood clotting. He predicted that the preventive use of Polygal tablets would reduce bleeding from gunshot wounds sustained during combat or surgery. Subjects were given a Polygal tablet, shot through the neck or chest, or had their limbs amputated without anesthesia. Rascher published an article on his experience of using Polygal, without detailing the nature of the human trials and set up a company staffed by prisoners to manufacture the substance.[25]

Bruno Weber was the head of the Hygienic Institution at Block 10 in Auschwitz and injected his subjects with blood types that were differed from their own. This caused the blood cells to congeal, and the blood was studied. When the Nazis removed blood from someone, they often entered a major artery, causing the subject to die of major blood loss.[18]

Electroshock experiments

Some female prisoners of Block 10 were also subject to electroshock therapy. These women were often sick and underwent this experimentation before being sent to the gas chambers and killed.[18]

Other experiments

Mengele's eye experiments included attempts to change the eye color by injecting chemicals into the eyes of living subjects, and he killed people with heterochromatic eyes so that the eyes could be removed and sent to Berlin for study.[26] His experiments on dwarfs and people with physical abnormalities included taking physical measurements, drawing blood, extracting healthy teeth, and treatment with unnecessary drugs and X-rays.[27] Many of his victims were dispatched to the gas chambers after about two weeks, and their skeletons were sent to Berlin for further analysis.[28] Mengele sought out pregnant women, on whom he would perform experiments before sending them to the gas chambers.[29] Alex Dekel, a survivor, reports witnessing Mengele performing vivisection without anesthesia, removing hearts and stomachs of victims.[30] Yitzhak Ganon, another survivor, reported in 2009 how Mengele removed his kidney without anesthesia. He was forced to return to work without painkillers.[31]

Aftermath

Other documented transcriptions from Heinrich Himmler include phrases such as "These researches… can be performed by us with particular efficiency because I personally assumed the responsibility for supplying asocial individuals and criminals who deserve only to die from concentration camps for these experiments."[32] Many of the subjects died as a result of the experiments conducted by the Nazis, while many others were murdered after the tests were completed to study the effects post mortem.[33] Those who survived were often left mutilated, suffering permanent disability, weakened bodies, and mental distress.[11][34] On 19 August 1947, the doctors captured by Allied forces were put on trial in USA vs. Karl Brandt et al., commonly known as the Doctors' Trial. At the trial, several of the doctors argued in their defense that there was no international law regarding medical experimentation.[citation needed] Some doctors also claimed that they had been doing the world a favor. An SS doctor was quoted saying that "Jews were the festering appendix in the body of Europe." He then went on to argue he was doing the world a favor by eliminating them.[35]

The issue of informed consent had previously been controversial in German medicine in 1900, when Albert Neisser infected patients (mainly prostitutes) with syphilis without their consent. Despite Neisser's support from most of the academic community, public opinion, led by psychiatrist Albert Moll, was against Neisser. While Neisser went on to be fined by the Royal Disciplinary Court, Moll developed "a legally based, positivistic contract theory of the patient-doctor relationship" that was not adopted into German law.[36] Eventually, the minister for religious, educational, and medical affairs issued a directive stating that medical interventions other than for diagnosis, healing, and immunization were excluded under all circumstances if "the human subject was a minor or not competent for other reasons", or if the subject had not given his or her "unambiguous consent" after a "proper explanation of the possible negative consequences" of the intervention, though this was not legally binding.[36]

In response, Drs. Leo Alexander and Andrew Conway Ivy, the American Medical Association representative at the Doctors' Trial, drafted a ten-point memorandum entitled Permissible Medical Experiment that went on to be known as the Nuremberg Code.[37] The code calls for such standards as voluntary consent of patients, avoidance of unnecessary pain and suffering, and that there must be a belief that the experimentation will not end in death or disability.[38] The Code was not cited in any of the findings against the defendants and never made it into either German or American medical law.[39] This code comes from the Nuremberg Trials where the most heinous of Nazi leaders were put on trial for their war crimes.[40] To this day, the Nuremberg Code remains a major stepping stone for medical experimentation.[41]

Modern ethical issues

Andrew Conway Ivy stated the Nazi experiments were of no medical value.[42] Data obtained from the experiments, however, has been used and considered for use in multiple fields, often causing controversy. Some object to the data's use purely on ethical grounds, disagreeing with the methods used to obtain it, while others have rejected the research only on scientific grounds, criticizing methodological inconsistencies.[42] Those in favor of using the data argue that if it has practical value to save lives, it would be equally unethical not to use it.[12] Arnold S. Relman, editor of The New England Journal of Medicine from 1977 till 1991, refused to allow the journal to publish any article that cited the Nazi experiments.[42]

| "I don't want to have to use the Nazi data, but there is no other and will be no other in an ethical world ... not to use it would be equally bad. I'm trying to make something constructive out of it." —Dr John Hayward, justifying citing the Dachau freezing experiments in his research.[12] |

The results of the Dachau freezing experiments have been used in some late 20th century research into the treatment of hypothermia; at least 45 publications had referenced the experiments as of 1984, though the majority of publications in the field did not cite the research.[42] Those who have argued in favor of using the research include Robert Pozos from the University of Minnesota and John Hayward from the University of Victoria.[12] In a 1990 review of the Dachau experiments, Robert Berger concludes that the study has "all the ingredients of a scientific fraud" and that the data "cannot advance science or save human lives."[42]

In 1989, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considered using data from Nazi research into the effects of phosgene gas, believing the data could help US soldiers stationed in the Persian Gulf at the time. They eventually decided against using it, on the grounds it would lead to criticism and similar data could be obtained from later studies on animals. Writing for Jewish Law, Baruch Cohen concluded that the EPA's "knee-jerk reaction" to reject the data's use was "typical, but unprofessional", arguing that it could have saved lives.[12]

Controversy has also risen from the use of results of biological warfare testing done by the Imperial Japanese Army's Unit 731.[43] The results from Unit 731 were kept classified by the United States until the majority of doctors involved were given pardons.[44]

See also

- Belmont Report

- Common Rule

- Declaration of Helsinki

- Doctors' Trial

- Human subject research

- Informed consent

- Nuremberg Code

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Amdur, Robert J., and Elizabeth A. Bankert. 2022. Institutional Review Book: Member Handbook, 4th Edition. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bardett Learning.

- Astor, Gerald. 1985. Last Nazi: Life and Times of Dr Joseph Mengele. New York: Donald I. Fine. ISBN 978-0-917657-46-7.

- Baron, Saskia (Director). 2001. Science and the Swastika: The Deadly Experiment. Documentary by Darlow Smithson Productions.

- Berger, Robert L. 1990. Nazi science: the Dachau hypothermia experiments. New England Journal of Medicine 322(20): 1435-1440. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- Bogod, David. 2004. The Nazi hypothermia experiments: forbidden data? Anaesthesia 59(12): 1155-1156.

- Jewish Virtual Library. n.d. Nazi medical experiments: freezing experiments. Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- Kubica, Helena. 1998. The Crimes of Josef Mengele. In Y. Gutman and M. Berenbaum (Eds.), Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20884-2.

- Lifton, Robert Jay. 1985. What Made This Man? Mengele. The New York Times July 21, 1985. Retrieved January 11, 2014.

- Mozes-Kor, Eva. 1992. Mengele Twins and Human Experimentation: A Personal Account. Pages 53-59 in George J. Annas and Michael A. Grodin (eds.), The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-510106-5.

- NMT Prosecution (Nuremberg Military Tribunals). 1947a. Table of contents for prosecution Document Book 8, concerning medical experiments. The Harvard Law School Library's Nuremberg Trials Project. HLSL Item No.: 4121. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- NMT Prosecution (Nuremberg Military Tribunals). 1947b. List of prosecution documents in Document Book 4, on malaria experiments. The Harvard Law School Library's Nuremberg Trials Project. HLSL Item No.: 68. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- NMT Prosecution (Nuremberg Military Tribunals). 1947c. List of documents in Document Book 2: High altitude experiments. The Harvard Law School Library's Nuremberg Trials Project. HLSL Item No.: 25. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- NMT Prosecution (Nuremberg Military Tribunals). 1947d. Deposition concerning medical experiments at Ravensbrueck (bone/muscle/nerve experiments). Deposition of Jadwiga Kaminska The Harvard Law School Library's Nuremberg Trials Project. HLSL Item No.: 2055. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- Perper, Joshua A., and Stephen J. Cina. 2010. When Doctors Kill: Who, Why, and How. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781441913692.

- Posner, Gerald L. and John Ware. 1986. Mengele: The Complete Story. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-050598-8.

- Small, Martin and Vic Shayne. 2009. Remember Us: My Journey from the Shtetl through the Holocaust. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 781602397231.

- Steinbacher, Sybille. 2005. Auschwitz: A History. Munich: Verlag C. H. Beck. ISBN 978-0-06-082581-2.

- Tyson, Peter. 2000. Holocaust on trial: the experiments. NOVA Online. Retrieved October 7, 2021.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. n.d. Nuremberg Code. [United States Holocaust Memorial Museum note]. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2006. Nazi medical experiments. Washington, D.C: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- University of Toronto. n.d. Ravensbruck. 74 cases of medical experiments conducted on the Polish political prisonersin women's concentration camp. Women's concentration camp medical experiment victims. University of Toronto. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- Wachsmann, Nikolaus. 2015. A History of the Nazi Concentration Camps. New York, NY: Farrar Straus & Giroux. ISBN 978-0374118259.

- Weindling, Paul J. 2011. The Nazi Medical Experiments. Chapter 2, pages 18-30 in Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Christine C. Grady, Robert A. Crouch, Reidar k. Lie, Franklin G. Miller, and David D Wendler (Eds.), The Oxford Textbook of Clinical Research Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199721665.

- ↑ (7 May 1992) The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code : Human Rights in Human Experimentation: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-977226-1.

- ↑ (1946) Nazi conspiracy and aggression: Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality. U.S. Govt. Print. Off..

- ↑ Malaria Experiments (in en).

- ↑ Nazi Medical Experiments. ushmm.org.

- ↑ (December 2019) Experimental infections in humans—historical and ethical reflections. Tropical Medicine & International Health 24 (12): 1384–1390.

- ↑ Epidemic Jaundice Experiments (in en).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Introduction to NMT Case 1: U.S.A. v. Karl Brandt et al.. Harvard Law Library, Nuremberg Trials Project: A Digital Document Collection.

- ↑ Schaefer, Naomi. The Legacy of Nazi Medicine, The New Atlantis, Number 5, Spring 2004, pp. 54–60.

- ↑ Spitz, Vivien (2005). Doctors from Hell: The Horrific Account of Nazi Experiments on Humans. Sentient Publications. ISBN 978-1-59181-032-2. “sulfonamide nazi tetanus.”

- ↑ Sea Water Experiments (in en).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNOVA - ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Cohen, Baruch C.. The Ethics of Using Medical Data From Nazi Experiments. Jewish Law: Articles.

- ↑ "Nuremberg - Document Viewer - Affidavit concerning the seawater experiments". nuremberg.law.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ↑ Gardella JE. The cost-effectiveness of killing: an overview of Nazi "euthanasia." Medical Sentinel 1999;4:132-5

- ↑ Dahl M. [Selection and destruction-treatment of "unworthy-to-live" children in the Third Reich and the role of child and adolescent psychiatry], Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr 2001;50:170-91.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:2 - ↑ Piotrowski, Christa (21 July 2000). Dark Chapter of American History: U.S. Court Battle Over Forced Sterilization. CommonDreams.org News Center.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Lifton, Robert Jay, 1926- author. (16 May 2017). The Nazi doctors : medical killing and the psychology of genocide. ISBN 978-0-465-09339-7. OCLC 1089625744.

- ↑ Meric, Vesna. "Forced to take part in experiments", BBC News, 27 January 2005.

- ↑ Medical Experiments at Auschwitz. Jewish Virtual Library.

- ↑ "Medicine and Murder in the Third Reich". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ↑ Cockburn, Alexander (1998). Whiteout:The CIA, Drugs, and the Press. Verso. ISBN 978-1-85984-139-6.

- ↑ "Documents Regarding Nazi Medical Experiments". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-04-14

- ↑ "Nuremberg - Document Viewer - Letter to Sigmund Rascher concerning the high altitude experiments". nuremberg.law.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ↑ Michalczyk, p. 96

- ↑ Lifton 1986, p. 362.

- ↑ Astor 1985, p. 102.

- ↑ Lifton 1986, p. 360.

- ↑ Brozan 1982.

- ↑ Lee 1996, p. 85.

- ↑ Schult 2009.

- ↑ "Nuremberg - Document Viewer - Letter to Erhard Milch concerning the high altitude and freezing experiments". nuremberg.law.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-14.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Jennifer. Mengele's Children – The Twins of Auschwitz. about.com.

- ↑ Sterilization Experiments. Jewish Virtual Library.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:1 - ↑ 36.0 36.1 Vollman, Jochen. Informed consent in human experimentation before the Nuremberg code. BMJ.

- ↑ The Nuremberg Code. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ↑ Regulations and Ethical Guidelines: Reprinted from Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, Vol. 2, pp. 181–182. Office of Human Subjects Research. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office (1949).

- ↑ Ghooi, Ravindra B. (2011-01-01). The Nuremberg Code–A critique. Perspectives in Clinical Research 2 (2): 72–76.

- ↑ The Nuremberg Trials (in en).

- ↑ Nuremberg Code – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (in en).

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBerger - ↑ "Unit 731: Japan's biological force", BBC News, 1 February 2002.

- ↑ Reilly, Kevin (2003). Racism: A Global Reader. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1059-1.

Further reading

- Annas, George J. (1992). The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195101065.

- Baumslag, N. (2005). Murderous Medicine: Nazi Doctors, Human Experimentation, and Typhus. Praeger Publishers. Template:ISBN

- Michalczyk, J. (Dir.) (1997). In The Shadow of the Reich: Nazi Medicine. First Run Features. (video)

- Nyiszli, M. (2011). "3", Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. New York: Arcade Publishing.

- Rees, L. (2005). Auschwitz: A New History. Public Affairs. Template:ISBN

- Weindling, P.J. (2005). Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent. Palgrave Macmillan. Template:ISBN

- USAF School of Aerospace Medicine (1950). German Aviation Medicine, World War II. United States Air Force.

External links

- The Infamous Medical Experiments from Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: "Forget You Not"

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Online Exhibition: Doctors Trial

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Online Exhibition: Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Library Bibliography: Medical Experiments

- Jewish Virtual Library: Medical Experiments Table of Contents

Controversy regarding use of findings

- Campell, Robert. "Citations of shame; scientists are still trading on Nazi atrocities", New Scientist, 28 February 1985, 105(1445), p. 31.Citations of shame; scientists are still trading on Nazi atrocities[1]

- "Citing Nazi 'Research': To Do So Without Condemnation Is Not Defensible"

- "On the Ethics of Citing Nazi Research"

- "Remembering the Holocaust, Part 2"

- "The Ethics Of Using Medical Data From Nazi Experiments"

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Nazi_human_experimentation history

- Nazi_Germany history

- Nazi_concentration_camps history

- Josef_Mengele history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.