Moldova

| Republica Moldova Republic of Moldova | |||||

| |||||

| Motto: Limba noastră-i o comoară Our language is a treasure | |||||

| Anthem: Limba noastră (Romanian) Our Language | |||||

| Capital | Chişinău 47°0′N 28°55′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Moldovan1 (Romanian) | ||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||

| - President | Vladimir Voronin | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Vasile Tarlev | ||||

| Independence from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - Date | August 27, 1991 | ||||

| - Finalised | December 25, 1991 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 33,843 km² (139th) 13,067 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 1.4 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2007 estimate | 4,320,490 | ||||

| - 2004 census | 3,383,3322 | ||||

| - Density | 111/km² 339/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $9,367 million | ||||

| - Per capita | $2,962 | ||||

| HDI (2006) | 0.694 (medium) | ||||

| Currency | Moldovan leu (MDL)

| ||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .md | ||||

| Calling code | +373 | ||||

The Republic of Moldova (Republica Moldova) is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, located between Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east and south.

Historically part of the Principality of Moldavia, it was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. At the dissolution of the Russian Empire in 1918, it united with other Romanian lands in Romania. After being occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, and changing hands in 1941 and 1944 during World War II, it was known as the Moldavian SSR until 1991.

Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union on August 27, 1991. Although Moldova has been independent from the USSR since 1991, Russian forces have remained on Moldovan territory east of the Dniester River despite signing international obligations to withdraw.

It is the second-smallest of the former Soviet republics and the most densely populated. Moldova's economy resembles those of the Central Asian republics, rather than those of the other states on the western edge of the former Soviet Union.

Geography

At 13,067 square miles (33,843 square kilometers) Moldova is slightly larger than Maryland inthe United States.

The western border of Moldova is formed by the Prut river, which joins the Danube before flowing into the Black Sea. In the north-east, the Dniester is the main river, flowing through the country from north to south.

The country is landlocked, even though it is very close to the Black Sea. Most of Moldova's territory is a hilly plain cut deeply by many streams and rivers. While the northern part of the country is hilly, elevations never exceed 1410 feet (430 metres)—the highest point being the Dealul Bălăneşti at 1410 feet.

Moldova's proximity to the Black Sea gives it a mild and sunny climate. The summers are warm and long, with temperatures averaging about 68°F (20°C), and the winters are relatively mild and dry, with January temperatures averaging 24.8°F (-4°C). Annual rainfall, which ranges from around 24 inches (600 millimeters) in the north to 16 inches (400mm) in the south, can vary greatly; long dry spells are not unusual. The heaviest rainfall occurs in early summer and again in October; heavy showers and thunderstorms are common. Because of the irregular terrain, heavy summer rains often cause erosion and river silting.

Drainage in Moldova is to the south, toward the Black Sea lowlands, and eventually into the Black Sea, but only eight rivers extend more than 100 kilometers. Moldova's main river, the Dniester, is navigable throughout almost the entire country, and in warmer winters it does not freeze over. The Prut River is a tributary of the Danube River, which it joins at the far southwestern tip of the country.

Underground water, extensively used for the republic's water supply, includes about 2,200 natural springs. The terrain favours construction of reservoirs.

About 75 percent of Moldova is covered by a soil type called "black earth" or chernozem. In the northern highlands, more clay textured soils are found; in the south, red-earth soil is predominant. The soil becomes less fertile toward the south but can still support grape and sunflower production. Moldova's rich soil and temperate continental climate have made the country one of the most productive agricultural regions and a major supplier of agricultural products in the region.

Originally forested with virgin oak and beech forests called “Codru”, it has been extensively de-forested for agriculture during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Moldovan fauna includes about 14,800 species, out of which 461 species of vertebrates (mammals, 70; birds, 281; reptiles, 14; amphibians, 14; fishes, 82) and 14,339 species of invertebrates, including some 12,000 species of insects.

Landslides are a frequently ocurring natural hazard. There were 57 cases in 1998. Moldova's Soviet-era agricultural practices such as overuse of pesticides and artificial fertilizers were intended to increase agricultural output at all costs, without regard for the consequences. As a result, Moldova's soil and groundwater were contaminated by lingering chemicals, some of which (including DDT) have been banned in the West.

Such practices continue in Moldova. In the early 1990s, use of pesticides in Moldova averaged approximately 20 times that of other former Soviet republics and Western nations. In addition, poor farming methods, such as destroying forests to plant vineyards, have contributed to the extensive soil erosion to which the country's rugged topography is already prone.

Chişinău is the capital city and industrial and commercial centre of Moldova. With a population of 647,513, it is the largest city of Moldova and is located in the centre of the country, on the river Bîc. Economically, the city is the most prosperous in Moldova and is one of the main industrial centres and transportation hubs of the region. Other cities are Tiraspol (in Transnistria), Bălţi and Tighina.

History

Moldova, known in the past as Bessarabia and Moldavia, has a long and stormy history. The territory has been inhabited for thousands of years. The Indo-European invasion occurred around the year 2000 B.C.E. The original inhabitants were Cimmerians, and after them came Scythians. The people who settled in this area would later become the Dacians, Getae and Thyrsagetae, these being Thracian tribes.

In the seventh century B.C.E., Greek settlers established colonies in the region, mostly along the Black Sea coast and traded with the locals. Also, Celts settled in the southern region, their main city being Aliobrix.

Romans resisted

The first state that included the whole of Moldova was the Dacian kingdom of Burebista, a contemporary of Julius Caesar, in the 1st century B.C.E. After his death, the state was divided into smaller pieces and was only unified in the Dacian kingdom of Decebalus in the first century C.E. Although this kingdom was defeated by the Roman Empire in 106 C.E., it was never part of the empire and the Free Dacians resisted the Roman conquerors. The Romans built defensive earthen walls in the south to defend the Scythia Minor province against invasions.

The Roman Empire romanized parts of Dacia (via colonization and cultural influence) and some of the local tribes adopted the Latin language and customs. According to the theory of the Daco-Roman continuity the Latin culture and the Romance language (Romanian) would later spread to encompass the cultural area of the ancient Dacians, including the region of Bessarabia. Some historians deny this and the continuity of Latin-speaking people north of the Danube. For more, see Origin of Romanians.

In 270, the Roman authorities began to withdraw their forces from Dacia, due to the invading Goths and Carps. The Goths, a Germanic tribe, poured into the Roman Empire through Budjak (in present day Ukraine), which due to its geographic position and characteristics (mainly steppe), was swept by various nomadic tribes. From the fifth century it was overrun in turn by the Huns, the Avars, and the Bulgars. The influence of the Roman Empire (East Roman) did not die out until 567.

The Dark Ages

Lying on one of the principal land routes into Europe, from the third century until the eleventh century, the region was invaded numerous times. Those centuries were characterized by a terrible state of insecurity and mass movement of people. The period was later known as the "Dark Ages" of Europe.

In 561, the Avars captured the territory and executed the local ruler Mesamer. Following Avars, Slavs started to arrive in the region and establish settlements. Then, in 582, Onogur Bulgars settled in south-eastern Bessarabia and northern Dobruja, from which they moved to Moesia under pressure from the Khazars and formed the nascent region of Bulgaria. With the rise of the Khazars' state in the east, the invasions began to diminish and it was possible to create larger states. The southern part of Moldova remained under the influence of the First Bulgarian Empire until to the end of ninth century.

Between the eighth and tenth centuries, the southern part of Moldova was inhabitated by people from Balkan-Dunabian culture (the culture of the First Bulgarian Empire). Between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, Bessarabia is mentioned in European and Slav chronicles as part of Bolohoveni (north) and Brodnici (south) Voevodates, believed to be Vlach (Romanian) principalities of the early Middle Ages. Part of the area came under the rule of Kievan Rus between the tenth and twelfth centuries and later passed to the Galician princes.

The Tatar invasions of 1241 and 1290 led to a retreat of a big part of the population to the Eastern Carpathians and to Transylvania. Apparently, only one group east of the Prut river did not retreat to mountain regions — the Tigheci "republic", situated near the modern town of Cahul in the southwest of Bessarabia, preserved its autonomy even during the later Principality of Moldavia. From 1241 to the fourteenth century Moldavia was vassal to the Tatars.

Principality of Moldavia

The Mongols were defeated 1343. The Genoese founded fortified commercial outposts on the Dniester in the fourteenth century, paving the way for contact with Western culture. The region was included in the principality of Moldavia, which by 1392 established control over the fortresses of Cetatea Albă and Chilia, its eastern border becoming the river Dnister. In the latter part of the fourteenth century, the southern part of the region was for several decades part of Wallachia. The main dynasty of Walachia was called Basarab, from which the name Bessarabia originated.

In the fifteenth century, the entire region was a part of the principality of Moldavia. Ştefan cel Mare (Stephen the Great) ruled between 1457 and 1504, a period of nearly 50 years during which he won 32 battles defending his country virtually against all his neighbours (mainly the Ottomans and the Tatars, but also the Hungarians and the Poles), while losing only two. During this period, after each victory, he raised a monastery or a church close to the battlefield honoring Christianity. Many of these battlefields and churches, as well as old fortresses are situated in Moldova (mainly along the Dniester river).

Turkish invasion

In 1484, the Turks invaded and captured Chilia and Cetatea Albă (Akkerman in Turkish). This conquest was ratified by treaty (in 1503 and 1513), which annexed the shoreline southern part of Bessarabia, which was then divided into two sanjaks (districts) of the Ottoman Empire. In 1538, the Ottomans annexed more Bessarabian land in the south as far as Tighina, while the central and northern parts of Bessarabia, as part of the principality of Moldavia was formally a vassal of the Ottoman Empire.

Russian adminstration

Beginning with Peter I (the Great), the Russians occupied Moldavia five times between 1711 and 1812, during wars between Ottoman Empire, Russia, and Austria. By the Treaty of Bucharest of May 28, 1812 — concluding the Russo-Turkish War, 1806-1812 — the Ottoman Empire ceded the eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia to the Russian Empire. That region was then called Bessarabia. Prior to that year, the name was used only for approximately its southern one quarter, which had been under direct Ottoman control since 1484.

At the end of the Crimean War, in 1856, by the Treaty of Paris, two districts of southern Bessarabia were returned to Moldavia, Russia lost access to the Danube river. Many localities, including Chişinău (Kishinev), now fell in the border area. In 1859, Moldavia and Wallachia united as the Kingdom of Romania in 1866, including the Southern part of Bessarabia.

The Romanian War of Independence was fought in 1877-1878, with the help of the Russian allies. Although the treaty of alliance between Romania and Russia specified that Russia would respect the territorial integrity of Romania and not claim any part of Romania at the end of the war, by the Treaty of Berlin, the Southern part of Bessarabia again came under the control of Russia.

The Russians granted autonomy in 1818 which remained until 1828. A Moldavian boyar had been made governor and a Moldavian archbishop installed. However, Moldavian peasants fled across the Prut, to avoid any introduction of serfdom. A zemstvo system, introduced in 1869, provided some local autonomy. A policy of Russification in civil and ecclesiastical administration was pursued. Tsarist policy aimed at de-nationalization of the Romanian element by forbidding after the 1860s education and Mass in Romanian, but the effect was a low literacy rate (approxiumately 40 percent for males, and 10 percent for females).

Russian Tsarist authorities brought Bessarabia colonists such as Gagauz and Bulgars from the Ottoman Empire, Ukrainians from Podolia, Germans from the Rhine regions, and encouraged the settlement of Lipovans from Russia, Jews from Podolia and Galicia, as well as Russian nobles or retired military.

The kingdom of Romania was founded in 1881, formed a focus for Moldavian nationalism, but no active movement developed in Bessarabia until after the Russian Revolution of 1905. Chisinau flourished, although its large Jewish population suffered in a pogrom in 1903.

World War I and the Russian Revolution

Romania fought as Russia's ally during World War I. Bessarabia proclaimed support for the moderate Socialist Revolutionary Aleksandr Kerensky in March 1917, and in April the National Moldavian Committee demanded autonomy, land reform, and the use of the Romanian language. In November 1917, a council known as the Sfatul Tarii (Sfat) was set up modellled on the Kiev Rada. On December 15, 1917, the Sfat proclaimed Bessarabia an autonomous constituent republic of the Federation of Russian Republics.

Disorders caused by revolutionary Russian soldiers prompted the Sfat to seek Romanian military help, which prompted a Bolshevik occupied Chisinau in January 1918. Romanian forces drove the Bolsheviks out within two weeks, and on February 6 the Sfat proclaimed Bessarabia an independent Moldavian republic, cutting ties with Russia. Bessarabia united with the Kingdom of Romania the same year, and the union was recognized by a treaty, that was part of the Paris Peace Conference, signed on October 28, 1920, by Romania, Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan. Transnistria did not join Romania.

Moldavian ASSR created

The Soviet Union, created in December 1922, did not recognize Romania's right to the province, and in 1924 it established the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic on lands to the east of the Dniester River in the Ukrainian SSR. The Soviet government in 1924 established the Moldavian Autonomous Oblast, the capital of which was Balta, situated in present-day Ukraine. Seven months later, the oblast was upgraded to the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian ASSR), even though its population was only 30 percent ethnic Romanian. The capital remained at Balta until 1929, when it was moved to Tiraspol. The frontier along the Dniester river was closed,

The area was quickly industrialized, and because of the lack of a qualified workforce and engineering and pedagogical cadres, a significant migration from other Soviet republics occurred, predominantly Ukrainians and Russians. In particular, in 1928, of 14,300 industrial workers only about 600 were Moldovans.

Collectivization in MASSR was even more fast-paced than in Ukraine and was reported to be complete by summer 1931. This was accompanied by the deportation of about 2000 families to Kazakhstan.

In 1925 MASSR survived a famine, followed by the great famine of 1932-1933 (known as the Holodomor in Ukraine), with tens of thousands of Ukrainians and Romanians dying of starvation. During the famine thousands of inhabitants tried to escape over Dniester, despite the threat of being shot. On February 23, 1932, the most notable such incident happened near the village Olăneşti, when 40 persons were shot. This was reported in European newspapers by survivors. The Soviet side reported this as an escape of "kulak elements subdued by Romanian propaganda".

Romanian Bessarabia

Despite Romanian government land reforms that limited the maximum holding to 247 acres (100 hectares), Romanian Bessarabia languished economically. The closed border along the Dniester and the loss of Odessa as a port was a disaster.

World War II

On June 28, 1940, in accordance with the secret protocol of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact with Nazi Germany, Soviet troops marched in forcing Romania to evacuate its administration from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina. On July 11, Transnistria (where ethnic Romanians were the largest ethnic group), was joined to part of the autonomous Moldavian republic across the Dniester to form, in August, a Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (S.S.R.), coterminous with the present-day Moldova, with Chisinau as its capital. The southern and northern parts (which had significant Slavic and Turkic minorities) were transferred to the Ukrainian SSR.

Under an agreement between Germany and the Soviet Union, many Moldavians left, some Jews entered, and the whole German population was moved to western Poland. In July 1941, Romania, Germany's ally against the Soviet Union, reoccupied Bessarabia. By December 1942, it was governed as Romanian territory, although not formally annexed. Moldavian peasants from Transnistria, a new Romanian province between the Dniester and the Southern Buh, were settled on the farms of departed Germans. Numerous Jews were killed or deported.

The Moldavian SSR

The Soviet Union occupied Bessarabia in 1944, and the territory remained part of the USSR after WWII as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. Controlled from Moscow, the Communist Party promoted industrialization and the collectivization of agriculture, abolishing private ownership of land, and of the means of production and distribution. Secret police struck at nationalist groups. A wave of repression was aimed at the Romanian intellectuals who decided to remain in Moldova after the war and propaganda was directed against everything that was Romanian. Ethnic Russians and Ukrainians were encouraged to immigrate to the Moldavian SSR, especially to Transnistria. At the same time, most of the Moldovan industry was built in Transnistria, while in Bessarabia mostly agriculture was developed.

Government requisitioning of large amounts of agricultural products despite a poor harvest - induced a famine - with 300,000 victims - following the catastrophic drought of 1945-1947, and political and academic positions were given to members of non-Romanian ethnic groups (only 14 percent of the Moldavian SSR's political leaders were ethnic Romanians in 1946).

The conditions imposed became the basis of deep resentment toward Soviet authorities — a resentment that soon manifested itself. During Leonid I. Brezhnev's 1950-1952 tenure as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldavia (CPM), he put down a rebellion of ethnic Romanians by killing or deporting thousands of people and instituting forced collectivization. Although Brezhnev and other CPM first secretaries were largely successful in suppressing Moldovan/Romanian nationalism, Mikhail S. Gorbachev's administration facilitated the revival of the movement in the region. His policies of glasnost and perestroika created conditions in which national feelings could be openly expressed and in which the Soviet republics could consider reforms.

In 1970s and '80s Moldova received substantial investment from the USSR to develop industrial, scientific facilities, as well as housing. This allocation was influenced by the fact that Leonid Brezhnev (the effective ruler of the USSR from 1964 to 1982) was the Communist Party First Secretary in the Moldavian SSR in 1950s.

Popular front formed

The Moldovan Popular Front (commonly called the Popular Front), an association of independent cultural and political groups, formed in 1989. Large demonstrations by ethnic Romanians led to Romanian being designated the official language and the head of the CPM replaced. However, the increasing influence of ethnic Romanians, especially in Transnistria, prompted Slavic minorities to form the Yedinstvo-Unitatea (Unity) Intermovement in 1988, and in the south, the Gagauz, a Turkic-speaking minority, formed Gagauz Halkî (Gagauz People), in 1989.

The first democratic elections to the Moldavian SSR's Supreme Soviet were held on February 25, 1990. The Popular Front won a majority. Mircea Snegur, a communist, was elected chairman of the Supreme Soviet, and in September he became president of the republic. The reformist government that took over in May 1990 made changes that did not please the minorities, including changing the republic's name to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova.

Gagauzia and Transnistria secede

In August 1990, the Gagauz declared a separate "Gagauz Republic" (Gagauz-Yeri) in the south, around the city of Comrat. In September the people on the east bank of the Dniester River (with mostly Slavic population) proclaimed the "Dnestr Moldavian Republic" (commonly called the "Dnestr Republic") in Transnistria, with its capital at Tiraspol. Although the Supreme Soviet immediately declared these declarations null, both "republics" went on to hold elections. Meanwhile, approximately 50,000 armed Moldovan nationalist volunteers went to Transnistria, where widespread violence was temporarily averted by the intervention of the Russian 14th Army, headquartered in Chişinău.

Transnistria declares independence

The part of Moldova east of the Dniester River, Transnistria, declared independence from Moldova, but within the Soviet Union on September 2, 1990, as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic. The inhabitants, which included a larger proportion of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, feared the rise of nationalism in Moldova and the country's expected unification with Romania at the dissolution of the USSR. The declaration was declared void by then-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachov.

Moldova declares independence

In May 1991, the country's official name was changed to the Republic of Moldova (Republica Moldova). The name of the Supreme Soviet also was changed, to the Moldovan Parliament. During the 1991 August coup d'état in Moscow against Mikhail Gorbachev, commanders of the Soviet Union's Southwestern Theater of Military Operations attempted to impose a state of emergency in Moldova. They were overruled by the Moldovan government, which declared its support for Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who led the counter-coup in Moscow. On 27 August 27, 1991, after the coup's collapse, Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union.

Romania was the first state to recognize the independent Republic of Moldova – only a few hours, in fact, after the declaration of independence was issued by the Moldovan parliament. During that period a Movement for unification of Romania and the Republic of Moldova began in each country. In December of 1991, Moldova became a member of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States along with most of the former Soviet republics. Declaring itself a neutral state, it did not join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) military branch. At the end of that year, an ex-communist reformer, Mircea Snegur, won an unchallenged election for the presidency. Three months later, the country achieved formal recognition as an independent state at the United Nations.

In mid April 1992, in accordance with the agreements concerning the split of the military equipment of the former Soviet Union, Moldova created its own Defense Ministry. Most of the 14th Soviet Army's military equipment was to be retained by Moldova. In October, Moldova began to organize its own armed forces. The Soviet Union was falling apart quickly, and Moldova had to rely on itself to prevent the spread of violence from the "Dnestr Republic" to the rest of the country.

War of Transnistria

In March 1992, a brief war between Moldovan and Transnistrian separatist forces started in the region. Volunteers came from Russia and Ukraine to help the separatist side. A ceasefire for this war was negotiated by presidents Mircea Snegur and Boris Yeltsin in July. A demarcation line was to be maintained by a tripartite peacekeeping force (composed of Moldovan, Russian, and Transnistrian forces), and Moscow agreed to withdraw its 14th Army if a suitable constitutional provision were made for Transnistria. Also, Transnistria would have a special status within Moldova and would have the right to secede if Moldova decided to reunite with Romania.

Different coalitions

During the first 10 years of independence, Moldova was governed by coalitions of different parties, lead mostly by former communist officials.

In April 1992, the Parliament approved Moldova's membership in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and in a CIS charter on economic union. On July 28, Parliament ratified a new constitution, which went into effect August 27, 1994, and provided substantial autonomy to Transnistria and to Gagauzia.

Russia and Moldova signed an agreement in October 1994 on the withdrawal of Russian troops from Transnistria, but the Russian government did not ratify it; another stalemate ensued. Although the cease-fire remained in effect, further negotiations that included the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe and the United Nations made little progress.

The Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with the European Union (EU) came into force in July 1998 for an initial period of 10 years. It established the institutional framework for bilateral relations, set the principal common objectives, and called for activities and dialogue in a number of policy areas.

In the 2001 elections, the Communist Party of Moldova won the majority of seats in the Parliament and appointed Vladimir Voronin as president. After few years in power, relationships between Moldova and Russia deteriorated in November 2003 over the Transnistrian conflict. In the following election, held in 2005, the Communist party made a 180 degree turn and was re-elected on a pro-Western platform, with Voronin being re-elected to a second term as a president.

Government and politics

The 1994 constitution, which replaced the 1978 framework for a Soviet-style government, established Moldova as a parliamentary democracy, with a unicameral parliament of 104 members directly elected for four-year terms. The president, who is directly elected for a five-year term, and is the head of state and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The president shares executive power with the Council of Ministers (cabinet), which is led by the prime minister, who is designated by the president (after consultation with the parliamentary majority) and approved by parliament. The council implements domestic and foreign policy.

Moldova is a one party dominant state with the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova in power. The Communist Party of Moldavia, which was until 1990 the only legal party, was dissolved in 1991. A variety of political parties have emerged since independence, most based on ethnicity (such as the Gagauz People's Party) or advocacy of independence or unification with either Romania or Russia. As of 2007, the major parties and movements were: Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova, Christian-Democratic People's Party (Moldova), Movement for a Democratic and Prosperous Moldova, Democratic Forces Party, Party of Renaissance and Conciliation, Social Democratic party of Moldova, and the Liberal Party of Moldova.

The position of the break-away republic of Transnistria, relations with Romania and integration into the EU dominate the political agenda.

The judicial system comprises the Supreme Court of Justice (with members appointed by parliament), a Court of Appeal, and lower courts (whose members are appointed by the president). The Higher Magistrates' Council nominates judges and oversees their transfer and promotion.

Administrative divisions

Moldova is divided into 32 districts (raioane, singular raion); three municipalities (Bălţi, Chişinău, Tighina); and two autonomous regions (Găgăuzia and Transnistria). The cities of Comrat and Tiraspol also have municipality status, however not as first-tier subdivisions of Moldova, but as parts of the regions of Găgăuzia and Transnistria, respectively.

Transnistria is a de jure part of Moldova, as its independence is not recognized by any country, although de facto it is not controlled by the Moldovan government. It is administered by an unrecognized breakaway authority seeking closer ties with Russia, and its status is still disputed.

Elected district councils coordinate elected town and village councils and mayors who administer local government. The constitution guarantees the right to “preserve, develop and express citizens' ethnic, cultural, and linguistic and religious identity” and grants special autonomy to the Russian region on the left bank of the Dniester and to the Gagauz region.

Relations with Romania

In 1989, Romanian became the official language of Moldova, and after independence in 1991, the Romanian tricolor with a coat-of-arms (inspired by the coat of arms of Romania) was used as the flag, and the Romanian national anthem became the anthem of Moldova. Certain groups in both countries expected unification, and a Movement for unification of Romania and the Republic of Moldova began in both countries. Dual citizenship became an increasingly important issue following the 2003 local elections, and in November 2003, the Moldovan parliament passed a law that allowed Moldovans to acquire dual citizenship.

However, the initial enthusiasm in Moldova was tempered and, starting in 1993, Moldova started to distance itself from Romania. The constitution adopted in 1994 used the term "Moldovan language" instead of "Romanian" and changed the national anthem to Limba noastră. The 1996 attempt by Moldovan president Mircea Snegur to change the official language to "Romanian" was dismissed by the Moldovan Parliament as "promoting Romanian expansionism".

Foreign relations

Moldova has officially been a neutral country since its independence, and an early member of the NATO Partnership for Peace. The government has stated that Moldova has European aspirations but there has been little progress toward EU membership. On May 1, 2004, many EU enthusiasts waving the EU flags found their flags confiscated by police and some were arrested under the clause of "anti-nationalism." A Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with EU is the legal basis for EU relations with Moldova. The PCA came into force in July 1998 for an initial period of 10 years. Romanian President Traian Basescu is one of the strong advocates (at the EU level) for Moldova's bid to join the European Union. In June 2007 the Republic of Moldova joined the International Parliament for Safety and Peace.

Human rights

According to Amnesty International's 2007 annual report torture and ill-treatment were widespread and conditions in pre-trial detention were poor. A number of treaties protecting women's rights were ratified, but men, women and children continued to be trafficked for forcible sexual and other exploitation and measures to protect women against domestic violence were inadequate. Constitutional changes to abolish the death penalty were made. Freedom of expression was restricted and opposition politicians were targeted.

The United States Senate has held committee hearings on irregularities that marred elections in Moldova, including the arrest and harassment of opposition candidates, intimidation and suppression of independent media, and state run media bias in favor of candidates backed by the Moldovan Government.

State media coverage of the street protests in 2002 regarding the Communists’ attempt to reinstate obligatory study of the Russian language and to defend the cultural identity that the majority of Moldovans share with neighboring Romania was censored. In February 2002, in response to severe censorship of the state broadcaster Teleradio-Moldova (TVM), hundreds of TVM journalists went on strike in solidarity with the anti-communist opposition. In retribution, a few journalists and staff members were dismissed or suspended from the station.

However, in 2004 an improvement was made and the Moldovan Parliament removed Article 170 from the country's Criminal Code. Article 170 called for up to five years imprisonment for defamation.

According to the OSCE, the media climate in Moldova remained restrictive as of 2004. Authorities continued a long-standing campaign to silence independent opposition voices and movements. In a case widely criticized by human rights defenders, opposition politician Valeriu Pasat was sentenced to a 10-year prison term. The United States and human rights defenders from the European Union consider him a political prisoner, and an official statement from Russia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the judgment "striking in its cruelty".

The Republic of Moldova, as well as other states and NGOs claim that the government of Transnistria is authoritarian and has a poor human rights record, and is accused of arbitrary arrest and torture. With the stated aim of wanting to rectify its human rights record and bring it in line with European standards, Transnistria in 2006 established an ombudsman office. The 2007 Freedom in the World report, published by the US-based Freedom House, described Transnistria as a "non-free" territory, having an equally bad situation in both political rights and civil liberties.

Economy

Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in Europe despite recent progress from its small economic base. It enjoys a favorable climate and good farmland but has no major mineral deposits. As a result, the economy depends heavily on agriculture, featuring fruits, vegetables, wine, and tobacco. Moldova must import almost all of its energy supplies. Moldova's dependence on Russian energy was underscored at the end of 2005, when a Russian-owned electrical station in Moldova's separatist Transnistria region cut off power to Moldova and Russia's Gazprom cut off natural gas to Moldova in disputes over pricing.

The economy achieved 6 percent or more GDP growth every year from 2000-05, though this was based largely on consumption fueled by remittances received from Moldovans working abroad. Russia's decision to ban Moldovan wine and agricultural products, coupled with its decision to double the price Moldova paid for Russian natural gas, slowed GDP growth in 2006 and greatly exacerbated Moldova's economic troubles.

In 2004, the volume of investment in the telecommunications and information market in Moldova increased by 30.1 percent in comparison with 2003, achieving US$65.5-million.

Economic reforms have been slow because of corruption and strong political forces backing government controls; nevertheless, the government's primary goal of EU integration has resulted in some market-oriented progress. The economy remains vulnerable to higher fuel prices, poor agricultural weather, and the skepticism of foreign investors. Also, the presence of an illegal separatist regime in Moldova's Transnistria region continues to be a drag on the Moldovan economy.

Exports totalled $1.02-billion in 2006. Export commodities included foodstuffs, textiles, and machinery. Export partners included Russia 22.5 percent, Germany 12 percent, Italy 10.9 percent, Romania 10.6 percent, Ukraine 9.5 percent, and Belarus 5.6 percent.

Imports totalled $2.65-billion. Import commodities included mineral products and fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals, and textiles. Import partners included Russia 22 percent, Ukraine 17.8 percent, Romania 9.6 percent, Germany 9.2 percent, Italy 6.4 percent, Poland 4.6 percent.

Moldova ranks low in terms of commonly-used living standards and human development indicators in comparison with other transition economies, and continues to occupy one of the last places among European countries in income per capita.

Moldova remains the poorest country in Europe in terms of GDP per capita, which was US$2962 in 2006, a rank of 135 in the world. The unemployment rate in 2005 was 7.3 percent, with roughly 25 percent of working age Moldovans employed abroad. In 2005, about 29.5 percent of the population were under the absolute poverty line. Moldova is classified as medium in human development and is at the 113th spot in the list of 177 countries. The value of the Human Development Index (0.681) is below the world average.

Demographics

Population

Moldova had a population of 4,320,490 in 2007. Traditionally a rural country, Moldova gradually began changing its character under Soviet rule. As urban areas became the sites of new industrial jobs and of amenities such as clinics, the population of cities and towns grew. The new residents were not only ethnic Moldovans who had moved from rural areas but also many ethnic Russians and Ukrainians who had been recruited to fill positions in industry and government. Although Moldova is by far the most densely populated of the former Soviet republics (129 inhabitants per square kilometer in 1990, compared with 13 inhabitants per square kilometer for the Soviet Union as a whole), it has few large cities. Life expectancy at birth for the total population was 65.18 years in 2005.

Ethnicity

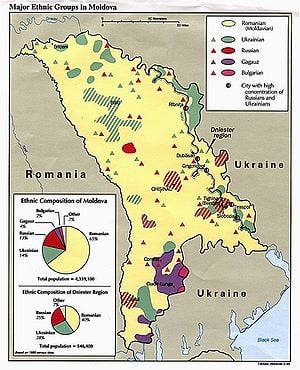

One of Moldova's characteristic traits is its ethnic diversity. The definition of ethnic groups is the subject of an ongoing dispute. The main controversy concerns the identity between Moldovans and Romanians, as well as between the corresponding Moldovan and Romanian languages (see Moldovan language). The distinction between Moldovans and Romanians has been a greatly disputed political issue with one side arguing that Moldovans constitute an ethnic group separate from the Romanian ethnos, whereas others claim that Moldovans in both Romania and Moldova are simply a subgroup of the Romanian ethnos, similar to Transylvanians, Oltenians, and other groups.

The 2004 Moldovan census describes ethnic groups in Moldova as follows: Moldovan/Romanian 78.2 percent, Ukrainian 8.4 percent, Russian 5.8 percent, Gagauz 4.4 percent, Bulgarian 1.9 percent, other 1.3percent.

Religions

The 2004 census shows that Eastern Orthodox make up 98.5 percent of the faithful, Judaism 1.5 percent, Baptist (only about 1,000 members) (1991) Percentages are calculated from the number of people declaring a religion; 75,727 (2.29 percent) of the population did not declare a religion. Orthodox Christians were not required in the census to declare the particular church they belong to. The Moldovan Orthodox Church, subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church, and the Orthodox Church of Bessarabia, autonomous and subordinated to the Romanian Orthodox Church, both claim to be the national church of the country.

The Soviet government strictly limited the activities of the Orthodox Church (and all religions) and at times sought to exploit it, with the ultimate goal of destroying it and all religious activity. Most Orthodox churches and monasteries in Moldova were demolished or converted to other uses, such as warehouses, and clergy were sometimes punished for leading services. But many believers continued to practice their faith in secret.

In 1991 Moldova had 853 Orthodox churches and eleven Orthodox monasteries (four for monks and seven for nuns). In addition, the Old Russian Orthodox Church had 14 churches and one monastery in Moldova.

There is no state religion, although the Moldovan Orthodox Church receives some favored treatment from the Government. The constitution provides for freedom of religion, and the Government generally respects this right in practice; however, the 1992 Law on Religions, which codifies religious freedoms, contains restrictions that inhibit the activities of unregistered religious groups.

Before the Holocaust, the country had a substantial Jewish community, seven percent, or slightly over 200,000, in 1930. In June-July 1941 approximately two thirds of the Jews fled (mostly in miserable conditions) to the interior of the USSR (Uzbekistan, Siberia, other regions) before the retreat of the Soviet troops. In 1941-1942, approximately one third of the Bessarabian Jews (alongside Jews from several other districts of Romania) were deported to ghettos and labor camps in Transnistria (WWII), where more than half perished in extreme conditions. Approximately 10,000 Jews (both military and civilians) were executed during the military action in June-July 1941 by German Einsatzkommando D, and (at least on four occasions) by Romanian troops. By mid 1942 fewer than 20,000 Jews remained in the region. After the Soviets took back the region in 1944, most of the Bessarabian Jews returned. During the Soviet period some Jews from Moldova moved to other parts of the former USSR, while some Jews from other regions moved to Moldova. During late 1980s and 1990s, there was mass migration of Jews to Israel, with a total number of emigrants estimated at over 100,000. The Jewish population was estimated at 1.5 percent as late as 2000.

Language

The state language, according to Title I, Article 13 of the Moldovan Constitution, is Moldovan. In Moldova's Declaration of Independence, the same language is called Romanian. There is no particular linguistic break at the Prut River, which divides Moldova from Romania. In formal use, the languages are identical except for minor orthographical issues (the Moldovans often, but not always, write î in some contexts where Romanians would use â; this same form used to be normal in Romania until 1993). There is, however, some regional variation, as might be found within any linguistic territory, and the common speech of areas such as Chişinău or Transnistria can be distinguished from the speech of Iaşi, a Romanian city that is also part of the former Principality of Moldavia, while the difference in the common speech between Iaşi and the capital of Romania Bucharest is even greater.

Linguistically, Moldovan is considered one the the five major spoken dialects of Romanian, all five being written identically. In general, before 1988-89, the less educated, the greater the difference from standard Romanian, and the more words were borrowed ad hoc from Russian into the daily speech.

A significant minority speaks native Russian, and there are more Slavicisms in common speech in Moldova than in common speech in Romania. Nonetheless, Moldovans are generally aware when they are using a word of Slavic origin not found in common Romanian, and are capable of choosing whether or not to use these words in a particular context.

In some cases Russian is used alongside Moldovan (Romanian) within state institutions, despite not having legal status. This is generally in direct relation to the political context in the government, which can be either pro-Russian or pro-Romanian/pro-Western. As of 2006, five members of the Moldovan government were not able to speak Moldovan, the main language used in government meetings being Russian. In Transnistria, the breakaway authorities consider its old Cyrillic form co-official with Russian and Ukrainian, and persecute inhabitants that use the standard Latin alphabet.

Men and women

Moldovan women do the domestic duties and child care as well as working outside the home. An extra task for women is preserving of food in the late summer to provide food for the winter. Although men seem to be the decision-makers at home and at work, women organize daily life, social gatherings, and gift-giving relations. Many women choose to give priority to their domestic duties.

Marriage and the family

When a young couple decides to marry, the girl often will go and stay at her boyfriend's house. Her parents are informed the next day, and the families meet to agree on the marriage, which may take place a couple of months later. Newlyweds live together with the groom's parents until they can can get their own home. In the villages, the youngest son and his family lives with the parents, and he inherits the house and contents. Otherwise, children inherit equally from their parents. Godparents are responsible for their godchildren through marriage and building a house.

In 1990, Moldova's divorce rate of 3.0 divorces per 1000 population had risen from the 1987 rate of 2.7 divorces per 1000 population (see table 9, Appendix A). The usual stresses of marriage were exacerbated by a society in which women were expected to perform most of the housework in addition to their work outside the home. Compounding this were crowded housing conditions (with their resulting lack of privacy) and, no doubt, the growing political crisis, which added its own strains.

Education

Bessarabia was one of the least-developed, and least-educated European regions of the Russian Empire. In 1930, its literacy rate was only 40 percent, according to a Romanian census. Although Soviet authorities promoted education to spread communist ideology, they also did everything they could to break the region's cultural ties with Romania.

The Soviet regime eradicated illiteracy and emphasized technical education to produce specialists and a highly skilled workforce for agriculture and industry. Before 1940 the republic had only one tertiary institute, a teacher-training college. By 2005, there were 16 state and 14 private institutions of higher education, with a total of 126,100 students, including 104,300 in the state, and 21,700 in the private ones.

The Moldova Academy of Sciences, established in Chisinau in 1961, coordinates the activities of some 16 scientific institutions. There are at least 50 centres researching viticulture, horticulture, beet growing, grain cultivation, and wine making.

In 2005, 99.1 percent of the total population age 15 and over could read and write.

Class

Large landowners (boyars) disappeared after the Soviet regime was established. After the Soviet Union collapsed, there emerged a wealthy class composed of former Soviet high-ranking officials, who appropriated state funds, and young entrepreneurs who amassed wealth on the introduction of a market economy. Moldovans tend to have higher positions in the government, while Russians dominate the private sector. New ornamented houses and villas, cars, cellphones, and fashionable clothes symbolize wealth. Consumer goods brought from abroad (Turkey, Romania, Germany) function as status symbols in cities and rural areas.

Culture

The culture of Moldova has been influenced by its Romanian origin, the roots of which reach back to the second century C.E., the period of Roman colonization in Dacia. During the Soviet era, the state directed cultural and intellectual life, meaning the theatre, motion pictures, television, and printed matter were censored and closely scrutinized.

Architecture

Chişinău's city center, built in the nineteenth century by the Russians, feature a neoclassical style of architecture. While there are numerous small one-story houses in the center, the outskirts are dominated by Soviet-style residential buildings. Small towns combine Soviet-style administration buildings and apartment blocks with typical Moldovan, Ukrainian, Gagauz, Bulgarian, or German houses, depending on their original inhabitants. Each house has a garden, a vineyard, and are surrounded by low metal ornamented bars.

Art

Sixteenth-century icons are the oldest examples of Moldovan graphic arts. Early twentieth century sculptor Alexandru Plămădeală and architect A. Şciusev contributed to the heritage of Bessarabian arts. Nineteenth and twentieth century Bessarabian painters worked on landscapes as well as Soviet realism. Since independence, artists including Valeriu Jabinski, Iuri Matei, Andrei Negur, and Gennadi Teciuc have appeared. Folk traditions, including ceramics and weaving, continue to be practiced in rural areas.

Cinema

Clothing

Cuisine and wine

The national dish is mamaliga, a hard corn porridge. It is poured onto a flat surface in the shape of a cake and is served with cheese, sour cream, or milk. Historically a peasant food, it was often used as a substitute for bread or even as a staple food in the poor rural areas. However, in the last decades it has emerged as an upscale dish available in the finest restaurants. Other main foods are a mixture of vegetables and meat (chicken, goose, duck, pork, and lamb), filled cabbage and grape leaves, and zama and Russian borsch soups. Plăcintă is a pastry filled with cheese, potatoes, or cabbage.

Moldova has a well established wine industry. The imprints of Vitis teutonica vine leaves near the Naslavcia village in the north of Moldova, prove that grapes have grown there approximately six to 25 million years ago. The size of the grape seed imprints found near the Varvarovca village and which date to 2800 B.C.E., prove that at that time the grapes were already cultivated. It has a vineyard area of 147,000 hectares (ha), of which 102,500 ha are in commercial production. Most of the country's wine production is for export. Many families have their own recipes and strands of grapes that have been passed on through generations.

Literature

Oral literature and folklore prevaled until the nineteenth century. The first Moldovan books (religious texts) appeared in the mid-seventeenth century. The Prince Dimitrie Cantemir (1673-1723), is one of the most important figures of Moldavian culture of the eighteenth century. Cantemir wrote the first geographical, ethnographical and economic description of the country in Descriptio Moldaviae (Berlin, 1714).

Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu (1838—1907) was a Romanian writer and philologist, who pioneered many branches of Romanian philology and history. Hasdeu is considered to have been able to understand 26 languages (many of which he could also converse in).

Mihai Eminescu (1850-89) was a late romantic poet, probably the best-known and most influential Romanian language poet.

Other prominent figures include author Ion Creangă (1837-1889), Vladimir Besleagă, Pavel Boţu, Aureliu Busuioc, Nicolae Dabija, Ion Druţă, Victor Teleuca and Grigore Vieru. In 1991, a total of 520 books were published in Moldova, of which 402 were in Romanian, 108 in Russian, eight in Gagauz, and two in Bulgarian.

Music

Moldovan music is closely related to that of its neighbour and cultural kin, Romania. Moldovan folk is known for swift, complex rhythms (a characteristic shared with many Eastern European traditions), musical improvisation, syncopation and much melodic ornamentation

During the Soviet era, Moldovan folk culture flourished, and was strongly promoted by the government. However, many elements were altered to obscure the shared history of Romania and Moldova, because the Soviet Union wanted to discourage secessionism. The Mioriţa is ancient ballad that is a very important part of Moldovan folk culture.

Pop, hip hop, rock and other modern genres have their own fans in Moldova as well. Modern pop stars include O-Zone, a Romanian and Moldovan band whose "Dragostea din tei" was a 2004 European hit, guitarist and songwriter Vladimir Pogrebniuc, Natalia Barbu, who is well-known in Germany, Romania and Ukraine, and Nelly Ciobanu. The band Flacai became well-known in the 1970s across Moldova, turning their hometown of Cahul into an important center of music.

Theatre

In the early 1990s, Moldova had twelve professional theaters. All performed in Romanian, except the A.P. Chekhov Russian Drama Theater in Chişinău, and the Russian Drama and Comedy Theater in Tiraspol, both of which performed solely in Russian, and the Licurici Republic Puppet Theater (in Chişinău), which performed in both Romanian and Russian. Although, among those controlled tendencies by Soviets, real artists in music formed real art-bands, such as "Ciocîrlia" led by Serghei Lunchevici (Loonkevich),and "Lăutarii" of Nicolae Botgros. Members of ethnic minorities manage a number of folklore groups and amateur theaters throughout the country.

Sport

Football has traditionally been Moldova's national sport, however, rugby union has risen to become a very popular sport with the national team earning promotion to Division one of the European Nations Cup with some brilliant displays attracting many spectators to their matches.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Aklaev, Airat R. "Dynamics of the Moldova-Trans-Dniestr-Conflict (late 1980s to early 1990s)." In Kumar Rupesinghe and Valery A. Tishkov, eds, Ethnicity and Power in the Contemporary World, 1996.

Batt, Jud. "Federalism versus Nationbuilding in Post-Communist State-Building: The Case of Moldova." Regional and Federal Studies 7 (3): 25–48, 1997.

Bruchis, Michael. One Step Back, Two Steps Forward: On the Language Policy of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in the National Republics, 1982.

——. "The Language Policy of the CPSU and the Linguistic Situation in Moldova." Soviet Studies 36 (1): 108–26, 1984.

——. Nations-Nationalities-People: A Study of the Nationalities Policy of the Communist Party in Soviet Moldavia, 1984.

——. The Republic of Moldavia from the Collapse of the Soviet Empire to the Restoration of the Russian Empire, 1997.

——. Chinn, Jeff. "The Case of Transdniestr." In Lena Jonson and Clive Archer, eds., Peacekeeping and the Role of Russia, 1996.

——and Steve Ropers. "Ethnic Mobilization and Reactive Nationalism: The Case of Moldova." Nationalities Papers 23 (2): 291–325, 1995.

Crowther, William. "Ethnic Politics and the Post-Communist Transition in Moldova." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 147–164, 1998.

——. "Moldova: Caught between Nation and Empire." In Ian Bremmer and Ray Tarasm, eds., New States, New Politics—Building the Post-Soviet Nations, 1997.

——. "The Construction of Moldovan National Consciousness." In Laszlo Kürti and Juliet Boulder Langman, eds., Beyond Borders: Remaking Cultural Identities in the New East and Central Europe, 1997.

——. "The Politics of Ethno-National Mobilization: Nationalism and Reform in Soviet Moldavia." Russian Review 50 (2): 183–202, 1991.

Dima, Nicholas. "Recent Ethno Demographic-Changes in Soviet Moldavia." East European Quarterly 25 (2): 167–178, 1991.

——. From Moldavia to Moldova, 1991.

——. "The Soviet Political Upheaval of the 1980s: The Case of Moldavia." Journal of Social Political and Economic Studies 16 (1): 39–58, 1991.

——. "Politics and Religion in Moldova: A Case-Study." Mankind Quarterly 34 (3): 175–194, 1994.

Dyer, Donald L., ed. Studies in Moldovan: The History, Culture, Language and Contemporary Politics of the People of Moldova, 1996.

——. "What Price Languages in Contact?: Is There Russian Language Influence on the Syntax of Moldovan?" Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 75–84, 1998.

Eyal, Jonathan. "Moldavians." In Graham Smith, ed., The Nationalities Question in the Soviet Union, 1990.

Feldman, Walter. "The Theoretical Basis for the Definition of Moldavian Nationality." In Ralph S. Clem, ed., The Soviet West: Interplay between Nationality and Social Organization, 1978.

"From Ethnopolitical Conflict to Inter-Ethnic Accord in Moldova." ECMI Report #1, March 1998.

Grupp, Fred W. and Ellen Jones. "Modernisation and Ethnic Equalisation in the USSR." Soviet Studies 26 (2): 159–184, 1984.

Hamm, Michael F. "Kishinev: The Character and Development of a Tsarist Frontier Town." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 19–37, 1998.

Helsinki Watch. Human Rights in Moldova: The Turbulent Dniester, 1993.

Ionescu, Dan. "Media in the Dniester Moldovan Republic: A Communist-Era Memento." Transitions 1 (19): 16–20, 1995.

Kaufman, Stuart J. "Spiraling to Ethnic War: Elites, Masses and Moscow in Moldova's Civil War." International Security 21 (2): 108–138, 1996.

King, Charles. "Eurasia Letter: Moldova with a Russian Face." Foreign Policy 97: 106–120, 1994.

——. "Moldova." In Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States, 1994.

——. "Moldovan Identity and the Politics of Pan-Romanianism." Slavic Review 53 (2): 345–368, 1994.

——. The Moldovans, Romania, Russia and the Politics of Culture, 2000.

——. Post-Soviet Moldova: A Borderland in Transition, 1995.

Kolstø, Pål. "The Dniestr Conflict: Between Irredentism and Separatism." Europe-Asia Studies 45 (6): 973–1000, 1993.

——. Andrei Malgin. "The Transnistrian Republic: A Case of Politicized Regionalism." Nationalities Papers 26 (1): 103–127, 1998.

Livezeanu, Irina. "Urbanization in a Low Key and Linguistic Change in Soviet Moldavia." Soviet Studies 33 (3): 327–351, 33 (4): 573–589, 1981.

Neukirch, Claus. "National Minorities in the Republic of Moldova—Some Lessons, Learned Some Not?" South East Europe Review for Labour and Social Affairs 2 (3): 45–64.

O'Loughlin, John, Vladimir Kolossov, and Andrei Tchepalyga. "National Construction, Territorial Separatism, and Post-Soviet Geopolitics in the Transdniester Moldovan Republic." Post-Soviet Soviet Geography and Economics 39 (6): 332–358, 1998.

Ozhiganov, Edward. "The Republic of Moldova: Transdniester and the 14th Army." In Alexei Arbatov, Abram Chayes, Antonia Handler Chayes, and Lara Olson, eds., Managing Conflict in the Former Soviet Union: Russian and American Perspectives, 1998.

Roach. A. "The Return of Dracula Romanian Struggle for Nationhood and Moldavian Folklore." History Today 38: 7–9, 1988.

Van Meurs, Wim P. "Carving a Moldavian Identity out of History." Nationalities Papers, 26 (1): 39–56, 1998.

——. The Bessarabian Question in Communist Historiography: Nationalist and Communist Politics and History-Writing, 1994.

Waters, Trevor. "On Crime and Corruption in the Republic of Moldova." Law Intensity Conflict and Law Enforcement 6 (2): 84–92, 1997.

External links

- Moldova World Fact Book 2007, accessed September 25, 2007.

- Moldova Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed September 25, 2007.

- Moldova Countries and Their Cultures Ma-Ni, accessed September 24, 2007.

- Official governmental site

- Official web site of the Parliament

- The EU's relations with Moldova (European Commission site)

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Embassy of the Republic of Moldova in the United States of America

- Embassy of the United States of America in the Republic of Moldova

- Elections in Moldova 2005

- General Local Elections 2007

- U.S. Department of State 2005 report about Human Rights in Moldova

Profiles

- U.S. Department of State Post Reports - Moldova

- CIA - The World Factbook - Moldova

- ECMI - Information about Minority Issues in Moldova

- Moldova ART Gallery by Anastasia Ponyatovskaya: icons, oil paintings, batik.All items are for sale,delivering is avalable

Others

- MOLDOVA 2006 INVESTMENT CLIMATE STATEMENT

- Moldova: Young Women From Rural Areas Vulnerable To Human Trafficking

- OurNet — Moldova Internet Resources

International rankings

- Bertelsmann: Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2006, ranked 75th out of 119 countries

- Reporters without borders: Annual worldwide press freedom index (2005), ranked 74th out of 167 countries

- The Wall Street Journal: 2005 Index of Economic Freedom, ranked 77th out of 155 countries

- The Economist: The World in 2005 - Worldwide quality-of-life index, 2005, ranked 99th out of 111 countries

- Transparency International: Corruption Perceptions Index 2005, ranked 88th out of 158 countries

- United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Index 2005, ranked 116th out of 177 countries

- World Economic Forum: Global Competitiveness Report 2005-2006 - Growth Competitiveness Index Ranking, ranked 82nd out of 117 countries

- World Bank: Doing Business 2006, ranked 83rd out of 155

- World Bank: Ease of Starting a Business 2006, ranked 69th out of 155

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Foreign Direct Investment Performance Index 2004, ranked 35th out of 140

| Geographic locale |

|

Template:Administrative divisions of Moldova Countries of Europe

Albania · Andorra · Armenia2 · Austria · Azerbaijan1 · Belarus · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Croatia · Cyprus2 · Czech Republic · Denmark3 · Estonia · Finland · France3 · Georgia1 · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Kazakhstan1 · Latvia · Liechtenstein · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Republic of Macedonia · Malta · Moldova · Monaco · Montenegro · Netherlands3 · Norway3 · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia1 · San Marino · Serbia · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain3 · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey1 · Ukraine · United Kingdom3 · Vatican City 1 Has majority of its territory in Asia. 2 Entirely in Asia but having socio-political connections with Europe. 3 Has dependencies or similar territories outside Europe. |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Moldova history

- Geography_of_Moldova history

- History_of_Moldova history

- Bessarabia history

- Transnistria history

- Politics_of_Moldova history

- Human_rights_in_Transnistria history

- Romanian-Moldovan_relations history

- Economy_of_Moldova history

- Demographics_of_Moldova history

- Culture_of_Moldova history

- Moldovan_wine history

- Music_of_Moldova history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.