Moldova

| Republica Moldova Republic of Moldova | |||||

| |||||

| Motto: Limba noastră-i o comoară Our language is a treasure | |||||

| Anthem: Limba noastră (Romanian) Our Language | |||||

| Capital | Chişinău 47°0′N 28°55′E | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | capital | ||||

| Official languages | Moldovan1 (Romanian) | ||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||

| - President | Vladimir Voronin | ||||

| - Prime Minister | Vasile Tarlev | ||||

| Independence from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - Date | August 27, 1991 | ||||

| - Finalised | December 25, 1991 | ||||

| Area | |||||

| - Total | 33,843 km² (139th) 13,067 sq mi | ||||

| - Water (%) | 1.4 | ||||

| Population | |||||

| - 2007 estimate | 4,320,490 | ||||

| - 2004 census | 3,383,3322 | ||||

| - Density | 111/km² 339/sq mi | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | ||||

| - Total | $9,367 million | ||||

| - Per capita | $2,962 | ||||

| HDI (2006) | 0.694 (medium) | ||||

| Currency | Moldovan leu (MDL)

| ||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||||

| - Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .md | ||||

| Calling code | +373 | ||||

The Republic of Moldova (Republica Moldova) is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe, located between Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east and south.

Historically part of the Principality of Moldavia, it was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. At the dissolution of the Russian Empire in 1918, it united with other Romanian lands in Romania. After being occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940, and changing hands in 1941 and 1944 during World War II, it was known as the Moldavian SSR until 1991.

Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union on August 27, 1991. Although Moldova has been independent from the USSR since 1991, Russian forces have remained on Moldovan territory east of the Dniester River despite signing international obligations to withdraw.

It is the second-smallest of the former Soviet republics and the most densely populated. Moldova's economy resembles those of the Central Asian republics, rather than those of the other states on the western edge of the former Soviet Union.

Geography

At 13,067 square miles (33,843 square kilometers) Moldova is slightly larger than Maryland inthe United States.

The western border of Moldova is formed by the Prut river, which joins the Danube before flowing into the Black Sea. In the north-east, the Dniester is the main river, flowing through the country from north to south.

The country is landlocked, even though it is very close to the Black Sea. Most of Moldova's territory is a hilly plain cut deeply by many streams and rivers. While the northern part of the country is hilly, elevations never exceed 1410 feet (430 metres)—the highest point being the Dealul Bălăneşti at 1410 feet.

Moldova's proximity to the Black Sea gives it a mild and sunny climate. The summers are warm and long, with temperatures averaging about 68°F (20°C), and the winters are relatively mild and dry, with January temperatures averaging 24.8°F (-4°C). Annual rainfall, which ranges from around 24 inches (600 millimeters) in the north to 16 inches (400mm) in the south, can vary greatly; long dry spells are not unusual. The heaviest rainfall occurs in early summer and again in October; heavy showers and thunderstorms are common. Because of the irregular terrain, heavy summer rains often cause erosion and river silting.

Drainage in Moldova is to the south, toward the Black Sea lowlands, and eventually into the Black Sea, but only eight rivers extend more than 100 kilometers. Moldova's main river, the Dniester, is navigable throughout almost the entire country, and in warmer winters it does not freeze over. The Prut River is a tributary of the Danube River, which it joins at the far southwestern tip of the country.

Underground water, extensively used for the republic's water supply, includes about 2,200 natural springs. The terrain favours construction of reservoirs.

About 75 percent of Moldova is covered by a soil type called "black earth" or chernozem. In the northern highlands, more clay textured soils are found; in the south, red-earth soil is predominant. The soil becomes less fertile toward the south but can still support grape and sunflower production. Moldova's rich soil and temperate continental climate have made the country one of the most productive agricultural regions and a major supplier of agricultural products in the region.

Originally forested with virgin oak and beech forests called “Codru”, it has been extensively de-forested for agriculture during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Moldovan fauna includes about 14,800 species, out of which 461 species of vertebrates (mammals, 70; birds, 281; reptiles, 14; amphibians, 14; fishes, 82) and 14,339 species of invertebrates, including some 12,000 species of insects.

Landslides are a frequently ocurring natural hazard. There were 57 cases in 1998.

Moldova's Soviet-era agricultural practices such as overuse of pesticides and artificial fertilizers were intended to increase agricultural output at all costs, without regard for the consequences. As a result, Moldova's soil and groundwater were contaminated by lingering chemicals, some of which (including DDT) have been banned in the West.

Such practices continue in Moldova. In the early 1990s, use of pesticides in Moldova averaged approximately 20 times that of other former Soviet republics and Western nations. In addition, poor farming methods, such as destroying forests to plant vineyards, have contributed to the extensive soil erosion to which the country's rugged topography is already prone.

Chişinău is the capital city and industrial and commercial centre of Moldova. With a population of 647,513, it is the largest city of Moldova and is located in the centre of the country, on the river Bîc. Economically, the city is the most prosperous in Moldova and is one of the main industrial centres and transportation hubs of the region. Other cities are Tiraspol (in Transnistria), Bălţi and Tighina.

History

Moldova, known in the past as Bessarabia and Moldavia, has a long and stormy history. The territory has been inhabited for thousands of years. The Indo-European invasion occurred around the year 2000 B.C.E. The original inhabitants were Cimmerians, and after them came Scythians. The people who settled in this area would later become the Dacians, Getae and Thyrsagetae, these being Thracian tribes.

In the seventh century B.C.E., Greek settlers established colonies in the region, mostly along the Black Sea coast and traded with the locals. Also, Celts settled in the southern region, their main city being Aliobrix.

Romans resisted

The first state that included the whole of Moldova was the Dacian kingdom of Burebista, a contemporary of Julius Caesar, in the 1st century B.C.E. After his death, the state was divided into smaller pieces and was only unified in the Dacian kingdom of Decebalus in the first century C.E. Although this kingdom was defeated by the Roman Empire in 106 C.E., it was never part of the empire and the Free Dacians resisted the Roman conquerors. The Romans built defensive earthen walls in the south to defend the Scythia Minor province against invasions.

The Roman Empire romanized parts of Dacia (via colonization and cultural influence) and some of the local tribes adopted the Latin language and customs. According to the theory of the Daco-Roman continuity the Latin culture and the Romance language (Romanian) would later spread to encompass the cultural area of the ancient Dacians, including the region of Bessarabia. Some historians deny this and the continuity of Latin-speaking people north of the Danube. For more, see Origin of Romanians.

In 270, the Roman authorities began to withdraw their forces from Dacia, due to the invading Goths and Carps. The Goths, a Germanic tribe, poured into the Roman Empire through Budjak (in present day Ukraine), which due to its geographic position and characteristics (mainly steppe), was swept by various nomadic tribes. From the fifth century it was overrun in turn by the Huns, the Avars, and the Bulgars. The influence of the Roman Empire (East Roman) did not die out until 567.

The Dark Ages

From the third century until the eleventh century, the region was invaded numerous times. Those centuries were characterized by a terrible state of insecurity and mass movement of people. The period was later known as the "Dark Ages" of Europe.

In 561, the Avars captured the territory and executed the local ruler Mesamer. Following Avars, Slavs started to arrive in the region and establish settlements. Then, in 582, Onogur Bulgars settled in south-eastern Bessarabia and northern Dobruja, from which they moved to Moesia under pressure from the Khazars and formed the nascent region of Bulgaria. With the rise of the Khazars' state in the east, the invasions began to diminish and it was possible to create larger states. The southern part of Moldova remained under the influence of the First Bulgarian Empire until to the end of ninth century.

Between the eighth and tenth centuries, the southern part of Moldova was inhabitated by people from Balkan-Dunabian culture (the culture of the First Bulgarian Empire). Between the ninth and thirteenth centuries, Bessarabia is mentioned in European and Slav chronicles as part of Bolohoveni (north) and Brodnici (south) Voevodates, believed to be Vlach (Romanian) principalities of the early Middle Ages.

The Tatar invasions of 1241 and 1290 led to a retreat of a big part of the population to the Eastern Carpathians and to Transylvania. Apparently, only one group east of the Prut river did not retreat to mountain regions at the time of the Tatar invasions. In later middle-age chronicles it is mentioned as the Tigheci "republic", situated near the modern town of Cahul in the southwest of Bessarabia, preserving its autonomy even during the later Principality of Moldavia.

The last large scale invasions were those of the Mongols and Tartars of 1241, 1290 and 1343, a small group of whom settled around the present day town of Orhei until they were pushed out in the 1390s.

Principality of Moldavia

After 1343 and the defeat of Mongols, the region was included in the principality of Moldavia, which by 1392 established control over the fortresses of Cetatea Albă and Chilia, its eastern border becoming the river Dnister (Nistru in Romanian). In the latter part of the fourteenth century, the southern part of the region was for several decades part of Wallachia. The main dynasty of Walachia was called Basarab, from which the name Bessarabia originated.

In the fifteenth century, the entire region was a part of the principality of Moldavia. Ştefan cel Mare (Stephen the Great) ruled between 1457 and 1504, a period of nearly 50 years during which he won 32 battles defending his country virtually against all his neighbours (mainly the Ottomans and the Tatars, but also the Hungarians and the Poles), while losing only two. During this period, after each victory, he raised a monastery or a church close to the battlefield honoring Christianity. Many of these battlefields and churches, as well as old fortresses are situated in Moldova (mainly along the Dniester river).

Turkish invasion

In 1484, the Turks invaded and captured Chilia and Cetatea Albă (Akkerman in Turkish), and annexed the shoreline southern part of Bessarabia, which was then divided into two sanjaks (districts) of the Ottoman Empire. In 1538, the Ottomans annexed more Bessarabian land in the south as far as Tighina, while the central and northern parts of Bessarabia, as part of the principality of Moldavia was formally a vassal of the Ottoman Empire.

Annexation by the Russian Empire

Between 1711 and 1812, the Russian Empire occupied the region five times during wars between Ottoman Empire, Russia, and Austria. By the Treaty of Bucharest of May 28, 1812 — concluding the Russo-Turkish War, 1806-1812 — the Ottoman Empire ceded the eastern half of the Principality of Moldavia to the Russian Empire. That region was then called Bessarabia. Prior to that year, the name was used only for approximately its southern one quarter, which had been under direct Ottoman control since 1484.

At the end of the Crimean War, in 1856, by the Treaty of Paris, two districts of southern Bessarabia were returned to Moldavia, Russia lost access to the Danube river. Many localities, including Chişinău (Kishinev), now fell in the border area. In 1859, Moldavia and Wallachia united as the Kingdom of Romania in 1866, including the Southern part of Bessarabia.

The Romanian War of Independence was fought in 1877-1878, with the help of the Russian allies. Although the treaty of alliance between Romania and Russia specified that Russia would respect the territorial integrity of Romania and not claim any part of Romania at the end of the war, by the Treaty of Berlin, the Southern part of Bessarabia again came under the control of Russia.

Bessarabia colonised

Russian Tsarist authorities brought Bessarabia colonists such as Gagauz and Bulgars from the Ottoman Empire, Ukrainians from Podolia, Germans from the Rhine regions, and encouraged the settlement of Lipovans from Russia, Jews from Podolia and Galicia, as well as Russian nobles or retired military. The Tsarist policy in Bessarabia was also partly aimed at de-nationalization of the Romanian element by forbidding after the 1860s education and Mass in Romanian, but the effect was a low literacy rate (approx. 40 percent for males, approx. 10 percent for females) rather than a denationalization.

Revolution and the Moldavian ASSR

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, Bessarabia proclaimed independence from Russia in 1918, and united with the Kingdom of Romania the same year. Transnistria did not join Romania. After the creation of the Soviet Union in December 1922, the Soviet government moved in 1924 to establish the Moldavian Autonomous Oblast on the lands to the east of the Dniester River in the Ukrainian SSR. The capital of the oblast was Balta, situated in present-day Ukraine. Seven months later, the oblast was upgraded to the Moldavian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian ASSR), even though its population was only 30 percent ethnic Romanian. The capital remained at Balta until 1929, when it was moved to Tiraspol.

The area was quickly industrialized, and because of the lack of a qualified workforce and engineering and pedagogical cadres, a significant migration from other Soviet republics occurred, predominantly Ukrainians and Russians. In particular, in 1928, of 14,300 industrial workers only about 600 were Moldovans.

Collectivization in MASSR was even more fast-paced than in Ukraine and was reported to be complete by summer 1931. This was accompanied by the deportation of about 2000 families to Kazakhstan.

In 1925 MASSR survived a famine, followed by the great famine of 1932-1933 (known as the Holodomor in Ukraine), with tens of thousands of Ukrainians and Romanians dying of starvation. During the famine thousands of inhabitants tried to escape over Dniester, despite the threat of being shot. On February 23, 1932, the most notable such incident happened near the village Olăneşti, when 40 persons were shot. This was reported in European newspapers by survivors. The Soviet side reported this as an escape of "kulak elements subdued by Romanian propaganda".

World War II

On June 28, 1940, in accordance with the secret protocol of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact with Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union forced Romania to evacuate its administration from Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina and immediately annexed these territories. The southern and northern parts (which had significant Slavic and Turkic minorities) were transferred to the Ukrainian SSR. At the same time, Transnistria (where ethnic Romanians were the largest ethnic group), was joined with the remaining territory to form the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, coterminous with the present-day Moldova.

Postwar reestablishment of Soviet control

The territory remained part of the USSR after WWII as the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic and the state imposed a harsh denationalization policy toward the native Romanian population. Several social and economic groups were targeted to be murdered, imprisoned, and deported to Siberia due to their economic situation, political views, or ties to the former regime. Secret police struck at nationalist groups; and ethnic Russians and Ukrainians were encouraged to immigrate to the Moldavian SSR, especially to Transnistria. At the same time, most of the Moldovan industry was built in Transnistria, while in Bessarabia mostly agriculture was developed.

The government's policies - requisitioning large amounts of agricultural products despite a poor harvest - induced a famine - with 300,000 victims - following the catastrophic drought of 1945-1947, and political and academic positions were given to members of non-Romanian ethnic groups (only 14% of the Moldavian SSR's political leaders were ethnic Romanians in 1946).

A wave of repression was aimed at the Romanian intellectuals that decided to remain in Moldova after the war and propaganda was directed against everything that was Romanian.

The conditions imposed during the reestablishment of Soviet rule became the basis of deep resentment toward Soviet authorities — a resentment that soon manifested itself. During Leonid I. Brezhnev's 1950-1952 tenure as the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Moldavia (CPM), he put down a rebellion of ethnic Romanians by killing or deporting thousands of people and instituting forced collectivization. Although Brezhnev and other CPM first secretaries were largely successful in suppressing Moldovan/Romanian nationalism, Mikhail S. Gorbachev's administration facilitated the revival of the movement in the region. His policies of glasnost and perestroika created conditions in which national feelings could be openly expressed and in which the Soviet republics could consider reforms.

In 1970s and '80s Moldova received substantial investment from the budget of the USSR to develop industrial, scientific facilities, as well as housing. In 1971 the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a decision "About the measures for further development of Kishinev city" that secured more than one billion rubles of investment from the USSR budget. Subsequent decisions that directed enormous wealth and brought highly qualified specialists from all over the USSR to develop Moldova. Such an allocation of USSR assets was influenced by the fact that Leonid Brezhnev (the effective ruler of the USSR from 1964 to 1982) was the Communist Party First Secretary in the Moldavian SSR in 1950s. These investments stopped in 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when Moldova became independent.

Increasing self-expression

In this climate of openness, political self-assertion escalated in the Moldavian SSR in 1988. The year 1989 saw the formation of the Moldovan Popular Front (commonly called the Popular Front), an association of independent cultural and political groups that had finally gained official recognition. Large demonstrations by ethnic Romanians led to the designation of Romanian as the official language and the replacement of the head of the CPM. However, opposition was growing to the increasing influence of ethnic Romanians, especially in Transnistria, where the Yedinstvo-Unitatea (Unity) Intermovement had been formed in 1988 by the Slavic minorities, and in the south, where Gagauz Halkî (Gagauz People), formed in November 1989, came to represent the Gagauz, a Turkic-speaking minority there (see Ethnic Composition, this ch.).

The first democratic elections to the Moldavian SSR's Supreme Soviet were held 25 February 1990. Runoff elections were held in March. The Popular Front won a majority of the votes. After the elections, Mircea Snegur, a communist, was elected chairman of the Supreme Soviet; in September he became president of the republic. The reformist government that took over in May 1990 made many changes that did not please the minorities, including changing the republic's name in June from the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic to the Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova and declaring it sovereign the same month.

Secession of Gagauzia and Transnistria

In August 1990 the Gagauz declared a separate "Gagauz Republic" (Gagauz-Yeri) in the south, around the city of Comrat. In September the people on the east bank of the Dniester River (with mostly Slavic population) proclaimed the "Dnestr Moldavian Republic" (commonly called the "Dnestr Republic") in Transnistria, with its capital at Tiraspol. Although the Supreme Soviet immediately declared these declarations null, both "republics" went on to hold elections. Stepan Topal was elected president of the "Gagauz Republic" in December 1991, and Igor' N. Smirnov was elected president of the "Dnestr Republic" in the same month.

Approximately 50,000 armed Moldovan nationalist volunteers went to Transnistria, where widespread violence was temporarily averted by the intervention of the Russian 14th Army. (The Soviet 14th Army, now the Russian 14th Army, had been headquartered in Chişinău under the High Command of the Southwestern Theater of Military Operations since 1956.) Negotiations in Moscow among the Gagauz, the Transnistrian Slavs, and the government of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova failed, and the government refused to join in further negotiations.

In May 1991, the country's official name was changed to the Republic of Moldova (Republica Moldova). The name of the Supreme Soviet also was changed, to the Moldovan Parliament.

Independence

image=Snegur ii.JPG During the 1991 August coup d'état in Moscow against Mikhail Gorbachev, commanders of the Soviet Union's Southwestern Theater of Military Operations attempted to impose a state of emergency in Moldova. They were overruled by the Moldovan government, which declared its support for Russian president Boris Yeltsin, who led the counter-coup in Moscow. On 27 August 1991, following the coup's collapse, Moldova declared its independence from the Soviet Union.

In October, Moldova began to organize its own armed forces. The Soviet Union was falling apart quickly, and Moldova had to rely on itself to prevent the spread of violence from the "Dnestr Republic" to the rest of the country. The December elections of Stepan Topal and Igor Smirnov as presidents of their respective "republics," and the official dissolution of the Soviet Union at the end of the year, led to increased tensions in Moldova.

At the end of 1991, an ex-communist reformer, Mircea Snegur, won an election for the presidency. Four months later, the country achieved formal recognition as an independent state at the United Nations.

Following independence in 1991, the Romanian tricolor with a coat-of-arms was used as the state flag, and Deşteaptă-te române!, the Romanian anthem also became the anthem of Moldova. During that period a Movement for unification of Romania and the Republic of Moldova began in each country.

In 1992, Moldova became involved in a brief conflict against local insurgents in Transnistria, who were aided by Russian armed forces and Ukrainian Cossacks. A ceasefire for this war was negotiated by presidents Mircea Snegur and Boris Yeltsin in July. A demarcation line was to be maintained by a tripartite peacekeeping force (composed of Moldovan, Russian, and Transnistrian forces), and Moscow agreed to withdraw its 14th Army if a suitable constitutional provision were made for Transnistria. Also, Transnistria would have a special status within Moldova and would have the right to secede if Moldova decided to reunite with Romania.

xxxx

In August 1991, Moldova declared its independence, and in December of that year became a member of the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States along with most of the former Soviet republics. Declaring itself a neutral state, it did not join the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) military branch. At the end of that year, an ex-communist reformer, Mircea Snegur, won an unchallenged election for the presidency. Three months later, the country achieved formal recognition as an independent state at the United Nations.

The part of Moldova east of the Dniester River, Transnistria, which included a larger proportion of ethnic Russians and Ukrainians, claimed independence in 1990, fearing the rise of nationalism in Moldova and the country's expected unification with Romania at the dissolution of the USSR. This caused a brief military conflict between Moldova and Transnistria in 1992. Russian forces intervened on the Transnistrian side, and Russian troops of the 14th Army remain there to this day. Negotiations between the Transnistrian and Moldovan leaders have been going on under the mediation of OSCE, Russia, Ukraine, European Union, and USA. Despite the expectations of the Popular Front of Moldova, Moldova did not unite with Romania in 1991. In the early 1990s, the future of Moldova was a source of tension in Romania's relations with Russia. A March 1994 referendum of the new constitution saw an overwhelming majority of voters favoring continued independence.

In 2001, the country became a member of the WTO. During the first 10 years of independence, Moldova was governed by coalitions of different parties, lead mostly by former communist officials which turned to democracy. In the 2001 elections, the Communist Party of Moldova won the majority of seats in the Parliament and appointed Vladimir Voronin as president. After few years in power, relationships between Moldova and Russia deteriorated in November 2003 over the Transnistrian conflict. In the following election, held in 2005, the Communist party made a 180 degree turn and was re-elected on a pro-Western platform, with Voronin being re-elected to a second term as a president. Since 1999, Moldova has constantly affirmed its desire to join the European Union, however it is not even part of the accession process yet, and the country's internal and foreign trade policy remains divided between the influence of Russia and that of the EU and USA.

Government

xxfrom introxxx Moldova is a parliamentary democracy with a President as its head of state and a Prime Minister as its head of government. The country is a member state of the United Nations, WTO, OSCE, GUAM, CIS, BSEC and other international organizations. xxx The Republic of Moldova is a relatively new state, which became independent after the break-up of the former Soviet Union. Historically, it traces its statehood to the medieval Principality of Moldavia (jointly with an equal size territory inside Romania), and to the Moldavian Democratic Republic (1917-1918), which chose to join Romania in 1918. In 1940, the Soviets created a puppet government under the name Moldavian SSR, which they placed inside the USSR as one of the 15 soviet republics. On 23 June, 1990, the first democratically elected parliament proclaimed Moldova's sovereignty, and on 27 August, 1991 the country's separation from the USSR, and independence.

Political system

The unicameral Moldovan parliament (Parlament) has 101 seats, and its members are elected by popular vote every four years. The parliament then elects a president, who functions as the head of state. The president appoints a prime minister as head of government who in turn assembles a cabinet, both subject to parliamentary approval. There is a large variety of political parties and movements in Moldova. As of 2007, the major parties and movements are:[citation needed]

- Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova

- Popular Christian Democratic Front

- Movement for a Democratic and Prosperous Moldova

- Democratic Forces Party

- Party of Renaissance and Conciliation

- Social Democratic party of Moldova

- Liberal Party of Moldova

2001 Parliamentary Elections

- Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) (50.07% votes, 71 mandates)

- Electoral Bloc "Braghiş Alliance" (BEAB) (13.36% votes, 19 mandates)

- Christian Democratic People's Party (CDPP) (8.24% votes, 11 mandates)

2005 Parliamentary Elections

- Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (PCRM) (45.98% votes, 56 mandates)

- Electoral Bloc “Moldova Democrată” (BMD) (28.53% votes, 34 mandates)

- Christian Democratic People's Party (CDPP) (9.07% votes, 11 mandates)

Relations with Romania/Identity Politics

In 1989, Romanian became the official language of Moldova (former Romanian Bessarabia). Following independence in 1991, the Romanian tricolor with a coat-of-arms (inspired by the coat of arms of Romania) was used as the flag, and Deşteaptă-te române!, the Romanian national anthem, also became the anthem of Moldova. In those times, there was an expectation among certain groups in both countries that they were to be united soon, and a Movement for unification of Romania and the Republic of Moldova began in both countries in the early 1990s. Dual citizenship became an increasingly important issue following the 2003 local elections, and in November 2003, the Moldovan parliament passed a law that allowed Moldovans to acquire dual citizenship.

In the address to the Romanian parliament in February 1991, Mircea Snegur, the Moldovan president spoke about a common identity of the Moldovans and Romanians, referring to the "Romanians of both sides of the Prut River" and "Sacred Romanian lands occupied by the Soviets". Historically, the Romanian government had provided scholarships to Moldovan students (via a common scheme with the Moldovan Ministry of Education) at all educational levels to attend Romanian schools and universities.

However, the initial enthusiasm in Moldova was tempered and, starting in 1993, Moldova started to distance itself from Romania. The constitution adopted in 1994 used the term "Moldovan language" instead of "Romanian" and changed the national anthem to Limba noastră. The 1996 attempt by Moldovan president Mircea Snegur to change the official language to "Romanian" was dismissed by the Moldovan Parliament as "promoting Romanian expansionism".

Foreign relations

The government has stated that Moldova has European aspirations but there has been little progress toward EU membership. On May 1, 2004 many EU enthusiasts waving the EU flags found their flags confiscated by police and some were arrested under the clause of "anti-nationalism." During her first bilateral visit to Moldova, European Commissioner for External Relations and European Neighbourhood Policy, Benita Ferrero-Waldner opened the new Delegation of the European Commission to Moldova on 6 October, to be headed by Cesare De Montis. A Partnership and Cooperation Agreement (PCA) with EU is the legal basis for EU relations with Moldova. The PCA came into force in July 1998 for an initial period of ten years. It establishes the institutional framework for bilateral relations, sets the principal common objectives, and calls for activities and dialog in a number of policy areas. Moldova welcomed EU enlargement and signed on 30 April 2004 the protocol extending the PCA to the new EU member states.

With the joint adoption of the EU-Moldova Action Plan on February 22, 2005, the EU and Moldova have further reinforced their bilateral relationship, providing a new tool to help implement the PCA and bring Moldova closer to the EU. The TACIS programme is used as the framework for technical assistance to support agreed objectives. Romanian President Traian Basescu is one of the strong advocates (at the EU level) for Moldova's bid to join the European Union.[1] In June 2007 the Republic of Moldova joined the International Parliament for Safety and Peace (see [1]and [2]).

Administrative divisions

Moldova is divided into thirty-two districts (raioane, singular raion); three municipalities (Bălţi, Chişinău, Tighina); and two autonomous regions (Găgăuzia and Transnistria). The cities of Comrat and Tiraspol also have municipality status, however not as first-tier subdivisions of Moldova, but as parts of the regions of Găgăuzia and Transnistria, respectively. The districts are:

|

|

|

|

Transnistria is a de jure part of Moldova, as its independence is not recognized by any country, although de facto it is not controlled by the Moldovan government. It is administered by an unrecognized breakaway authority seeking closer ties with Russia, and its status is still disputed.

Human rights

According to Amnesty International's 2007 annual report torture and ill-treatment were widespread and conditions in pre-trial detention were poor. A number of treaties protecting women's rights were ratified, but men, women and children continued to be trafficked for forcible sexual and other exploitation and measures to protect women against domestic violence were inadequate. Constitutional changes to abolish the death penalty were made. Freedom of expression was restricted and opposition politicians were targeted.

The United States Senate has held committee hearings on irregularities that marred elections in Moldova, including the arrest and harassment of opposition candidates, intimidation and suppression of independent media, and state run media bias in favor of candidates backed by the Moldovan Government.[2]

State media coverage of the street protests in 2002 regarding the Communists’ attempt to reinstate obligatory study of the Russian language and to defend the cultural identity that the majority of Moldovans share with neighboring Romania was censored. In February 2002, in response to severe censorship of the state broadcaster Teleradio-Moldova (TVM), hundreds of TVM journalists went on strike in solidarity with the anti-communist opposition. In retribution, a few journalists and staff members were dismissed or suspended from the station in March[3].

However, in 2004 an improvement was made and the Moldovan Parliament removed Article 170 from the country's Criminal Code. Article 170 called for up to five years imprisonment for defamation.[4]

According to the OSCE, the media climate in Moldova remained restrictive as of 2004.[5] Authorities continued a long-standing campaign to silence independent opposition voices and movements. In a case widely criticized by human rights defenders, opposition politician Valeriu Pasat was sentenced to a ten-year prison term. The United States and human rights defenders from the European Union consider him a political prisoner, and an official statement from Russia's Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the judgment "striking in its cruelty".[citation needed]

- See also: Human rights in Transnistria

Moldova has officially been a neutral country since its independence, and an early member of the NATO Partnership for Peace. Moldova currently aspires to join the European Union.

Economy

Moldova enjoys a favorable climate and good farmland but has no major mineral deposits. As a result, the economy depends heavily on agriculture, featuring fruits, vegetables, Moldovan wine, and tobacco. Moldova must import all of its supplies of petroleum, coal, and natural gas, largely from Russia. After the break up of the Soviet Union in 1991, energy shortages contributed to sharp production declines. As part of an ambitious economic liberalization effort, Moldova introduced a convertible currency, freed all prices, stopped issuing preferential credits to state enterprises, backed steady land privatization, removed export controls, and freed interest rates. The government entered into agreements with the World Bank and the IMF to promote growth. Recent trends indicate that the Communist government intends to reverse some of these policies, and recollectivise land while placing more restrictions on private business. The economy returned to positive growth, of 2.1% in 2000 and 6.1% in 2001. Growth remained strong in 2002, in part because of the reforms and because of starting from a small base. Further liberalization is in doubt because of strong political forces backing government controls. The economy remains vulnerable to higher fuel prices, poor agricultural weather, and the skepticism of foreign investors. In agriculture, the economic reform started with the land cadastre reform.

Following the regional financial crisis in 1998, Moldova has made significant progress towards achieving and retaining macroeconomic and financial stabilization. It has, furthermore, implemented many structural and institutional reforms that are indispensable for the efficient functioning of a market economy. These efforts have helped maintain macroeconomic and financial stability under difficult external circumstances, enabled the resumption of economic growth and contributed to establishing an environment conducive to the economy’s further growth and development in the medium term. Despite these efforts, and despite the recent resumption of economic growth, Moldova still ranks low in terms of commonly-used living standards and human development indicators in comparison with other transition economies. Although the economy experienced a constant economic growth after 2000: with 2.1%, 6.1%, 7,8% and 6,3% between 2000 and 2003 (with a forecast of 8% in 2004), one can observe that these latest developments hardly reach the level of 1994, with almost 40% of the GDP registered in 1990. Thus, during the last decade little has been done to reduce the country’s vulnerability. After a severe economic decline, social and economic challenges, energy uprooted dependencies, Moldova continues to occupy one of the last places among European countries in income per capita.

In 2002 (Human Development Report 2004), the registered GDP per capita was US $381, equivalent to US $ 1,470 PPP, which is 5.3 times lower than the world average (US $ 7,804). Moreover, GDP per capita is under the average of all regions in the world, including Sub-Saharan Africa (US $ 1,790 PPP). In 2004, about 40% of the population were under the absolute poverty line and registered an income lower than US $ 2.15 (PPP) per day. Moldova is classified as medium in human development and is at the 113th spot in the list of 177 countries. The value of the Human Development Index (0.681) is below the world average. Moldova remains the poorest country in Europe in terms of GDP per capita: $ 2,500 in 2006.[6]

Information technology and telecommunications

In 2004, the volume of investment in the telecommunications and information market in Moldova increased by 30.1% in comparison with 2003, achieving 825.3 million lei (65.5 million US dollars). The representatives of the National Agency for Telecommunications and Information Regulation stated that 451 million lei (35.9 million dollars) were invested in the field of fixed telephone communication. Investments constituted 330 million lei (26.2 million dollars) in the field of mobile telephony, 24.2 million lei (1.9 million dollars) in the field of Internet services, 19.1 million lei (1.5 million dollars) in the field of cable television services. An essential increase of 163 million lei (12.9 million dollars) has been achieved in the field of mobile telephony. In comparison with 2003, investments in this sector practically doubled. An insignificant increase was registered in the other market segments, but the investment volume remained the same in the field of fixed telephone communication.

In 2005, investments in telecommunication and information technology exceeded the level of the previous year, due to the investments by the national operator of the stationary telephone communications in the Joint-Stock Company Moldtelecom for the implementation of CDMA technology, the investments of the operators of mobile telephony Orange and Moldcell in the development of infrastructure, and the extension and improvement of Internet access services via new broadband technologies.

Demographics

Population

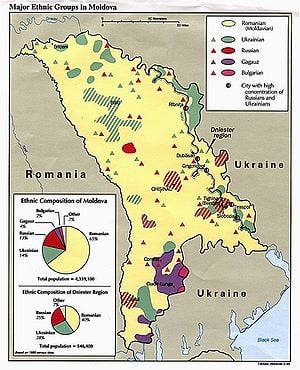

Ethnicity

Given that the definition of ethnic groups is the subject of an ongoing dispute, the following data must be treated with caution. The main controversy, concerns the identity between Moldovans and Romanians, as well as between the corresponding Moldovan and Romanian languages (see Moldovan language). The distinction between Moldovans and Romanians has been a greatly disputed political issue with one side arguing that Moldovans constitute an ethnic group separate from the Romanian ethnos, whereas others claim that Moldovans in both Romania and Moldova are simply a subgroup of the Romanian ethnos, similar to Transylvanians, Oltenians, and other groups (see Moldovans).

The last reference data is that of the 2004 Moldovan Census[7] and the 2004 Census in Transnistria:

| # | Ethnicity | Mold. census | % Mold | Transnistrian census | % Tran | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Moldovans | 2,564,849 | 75.8% | 177,156 | 31.9% | 2,742,005 | 69.6% |

| 2. | Ukrainians | 282,406 | 8.3% | 159,940 | 28.8% | 442,346 | 11.2% |

| 3. | Russians | 201,218 | 5.9% | 168,270 | 30.3% | 369,488 | 9.4% |

| 4. | Gagauzians | 147,500 | 4.4% | 11,107 | 2.0% | 158,607 | 4.0% |

| 5. | Romanians | 73,276 | 2.2% | NA | NA | 73,276 | 1.9% |

| 6. | Bulgarians | 65,662 | 1.9% | 11,107 | 2.0% | 76,769 | 1.9% |

| 7. | Others | 48,421 | 1.4% | 27,767 | 5.0% | 76,188 | 1.9% |

| 8. | TOTAL | 3,383,332 | 100% | 555,347 | 100% | 3,938,679 | 100% |

Note: Transnistrian authorities published only the percentage of ethnic groups; the number of people was calculated from those percentages. The number or percentage of Romanians in Transnistria was not published; it is included in "others".

According to the Moldova Azi news agency,[8] a group of international census experts described the 2004 Moldovan census as "generally conducted in a professional manner", while remarking that that "a few topics… were potentially more problematic", in particular:

- The census includes at least some Moldovans who had been living abroad over one year at the time of the census.

- * The precision of numbers about nationality/ethnicity and language was questioned. Some enumerators apparently encouraged respondents to declare that they were "Moldovan" rather than "Romanian", and even within a single family there may have been confusion about these terms. Also it is unclear how many respondents consider the term "Moldovan" to signify an ethnic identity other than "Romanian".

Religions

According to the 2004 census, the population of Moldova has the following religious composition:

| Religion | Adherents | % of total |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Orthodox Christians | 3,158,015 | 95.5% |

|

Newer Protestant faiths

|

|

1.83% |

|

Traditional Protestant

|

|

0.19% |

| Old-Rite Christians b | 5,094 | 0.15% |

| Roman Catholics | 4,645 | 0.14% |

| Muslims | 1,667 | 0.05% |

| Other religions | 25,527 | 0.77% |

| Agnostics | 33,207 | 1% |

| Atheists | 12,724 | 0.38% |

Percentages are calculated from the number of people declaring a religion; 75,727 (2.29%) of the population did not declare a religion.

a Known as Creştini după Evanghelie.

b Traditionally Orthodox Lipovans.

Orthodox Christians were not required in the census to declare the particular church they belong to. The Moldovan Orthodox Church, subordinated to the Russian Orthodox Church, and the Orthodox Church of Bessarabia, autonomous and subordinated to the Romanian Orthodox Church, both claim to be the national church of the country.

Before the Holocaust, the country had a substantial Jewish community, 7%, or slightly over 200,000, in 1930. In June-July 1941 approximately two thirds of the Jews fled (mostly in miserable conditions) to the interior of the USSR (Uzbekistan, Siberia, other regions) before the retreat of the Soviet troops. In 1941-1942, approximately one third of the Bessarabian Jews (alongside Jews from several other districts of Romania) were deported to ghettos and labor camps in Transnistria (WWII), where more than half perished in extreme conditions. Approximately 10,000 Jews (both military and civilians) were executed during the military action in June-July 1941 by German Einsatzkommando D, and (at least on four occasions) by Romanian troops. By mid 1942 fewer than 20,000 Jews remained in the region. After the Soviets took back the region in 1944, most of the Bessarabian Jews returned. During the Soviet period some Jews from Moldova moved to other parts of the former USSR, while some Jews from other regions moved to Moldova. During late 1980s and 1990s, there was mass migration of Jews to Israel, with a total number of emigrants estimated at over 100,000. The Jewish population was estimated at 1.5% as late as 2000.

Language

The state language, according to Title I, Article 13 of the Moldovan Constitution, is Moldovan. In Moldova's Declaration of Independence, the same language is called Romanian[9]. There is no particular linguistic break at the Prut River, which divides Moldova from Romania. In formal use, the languages are identical except for minor orthographical issues (the Moldovans often, but not always, write î in some contexts where Romanians would use â; this same form used to be normal in Romania until 1993). There is, however, some regional variation, as might be found within any linguistic territory, and the common speech of areas such as Chişinău or Transnistria can be distinguished from the speech of Iaşi, a Romanian city that is also part of the former Principality of Moldavia, while the difference in the common speech between Iaşi and the capital of Romania Bucharest is even greater. Linguistically, Moldovan is considered one the the five major spoken dialects of Romanian, all five being written identically. In general, before 1988-89, the less educated, the greater the difference from standard Romanian, and the more words were borrowed ad hoc from Russian into the daily speech.

Opinions vary on the status of Moldovan as a language. Most linguists consider standard Moldovan to be identical to standard Romanian, an Eastern Romance language, although one Moldovan linguist[10] disputes this. There are, however, more differences between the colloquial spoken languages of Moldova and Romania, most significantly due to the influence of Russian in Moldova which was not present in Romania. These differences in speech vocabulary are being slowly diluted after 1989. The matter of whether or not Moldovan is a separate language is a contested political issue within and beyond the Republic of Moldova. The 1989 law on language of the Moldavian SSR, which is still effective in Moldova according to the Constitution [11], asserts the existence of "linguistic Moldo-Romanian identity". [12] A significant minority speaks native Russian, and there are more Slavicisms in common speech in Moldova than in common speech in Romania. Nonetheless, Moldovans are generally aware when they are using a word of Slavic origin not found in common Romanian, and are capable of choosing whether or not to use these words in a particular context.

In some cases Russian is used alongside Moldovan (Romanian) within state institutions, despite not having legal status. This is generally in direct relation to the political context in the government, which can be either pro-Russian or pro-Romanian/pro-Western. As of 2006, five members of the Moldovan government were not able to speak Moldovan, the main language used in government meetings being Russian[13]. In Transnistria, the breakaway authorities consider its old Cyrillic form co-official with Russian and Ukrainian, and persecute inhabitants that use the standard Latin alphabet.

Men and women

Marriage and the family

Education

Class

Large landowners (boyars) disappeared after the Soviet regime was established. After the Soviet Union collapsed, there emerged a wealthy class composed of of former Soviet high-ranking officials, who appropriated state funds, and young entrepreneurs who amassed wealth on the introduction of a market economy. Moldovans tend to have higher positions in the government, while Russians dominate the private sector. New ornamented houses and villas, cars, cellphones, and fashionable clothes symbolize wealth. Consumer goods brought from abroad (Turkey, Romania, Germany) function as status symbols in cities and rural areas.

Culture

Located geographically at the crossroads of Latin and Slavic cultures, Moldova has enriched its own culture adopting and maintaining some of the traditions of its neighbors.

The Prince Dimitrie Cantemir is one of the most important figures of Moldavian culture of the 18th century. Cantemir wrote the first geographical, ethnographical and economic description of the country in Descriptio Moldaviae (Berlin, 1714).

Architecture

Art

Cinema

Clothing

Cuisine

Literature

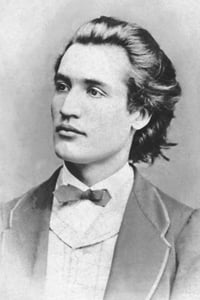

Mihai Eminescu was a late romantic poet, probably the best-known and most influential Romanian language poet.

Music

Sport

Football has traditionally been Moldova's national sport, however, rugby union has risen to become a very popular sport with the national team earning promotion to Division one of the European Nations Cup with some brilliant displays attracting many spectators to their matches.

See also

Template:Moldovan Topics

|

|

|

|

Gallery

Triumphal Arch, Chişinău

Notes

- ↑ Romania seeks German support for Moldova's bid to join EU People's Daily Online, 3 July 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Library of Congress, Senate report 2004

- ↑ Press freedom report (CPJ)

- ↑ Statement of Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ)

- ↑ Report on Assessment Visit to Moldova by the OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media

- ↑ CIA - The World Factbook - Moldova 6 Sep 2007

- ↑ (Romanian) Official results of 2004 Moldovan census

- ↑ Experts Offering to Consult the National Statistics Bureau in Evaluation of the Census Data, Moldova Azi, May 19, 2005, story attributed to AP Flux. Retrieved October 11, 2005.

- ↑ Template:Ro-iconDeclaraţia de independenţa a Republicii Moldova, Moldova Suverană

- ↑ Stati, V.N. Dicţionar moldovenesc-românesc. [=Moldovan-Romanian dictionary.] Chişinău: Tipografia Centrală (Biblioteca Pro Moldova), 2003. ISBN 9975-78-248-5.

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Moldova, Title 7, Article 7: "The law of 1 September 1989 regarding the usage of languages spoken on the territory of the Republic of Moldova remains valid, excepting the points where it contradicts this constitution."

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedlang law - ↑ Moldovan MPs say state functionaries that do not speak state language should be dismissed

External links

- Official governmental site

- Official web site of the Parliament

- The EU's relations with Moldova (European Commission site)

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- Embassy of the Republic of Moldova in the United States of America

- Embassy of the United States of America in the Republic of Moldova

- Elections in Moldova 2005

- General Local Elections 2007

- U.S. Department of State 2005 report about Human Rights in Moldova

Profiles

- U.S. Department of State Post Reports - Moldova

- CIA - The World Factbook - Moldova

- ECMI - Information about Minority Issues in Moldova

- Moldova ART Gallery by Anastasia Ponyatovskaya: icons, oil paintings, batik.All items are for sale,delivering is avalable

Others

- MOLDOVA 2006 INVESTMENT CLIMATE STATEMENT

- Moldova: Young Women From Rural Areas Vulnerable To Human Trafficking

- OurNet — Moldova Internet Resources

International rankings

- Bertelsmann: Bertelsmann Transformation Index 2006, ranked 75th out of 119 countries

- Reporters without borders: Annual worldwide press freedom index (2005), ranked 74th out of 167 countries

- The Wall Street Journal: 2005 Index of Economic Freedom, ranked 77th out of 155 countries

- The Economist: The World in 2005 - Worldwide quality-of-life index, 2005, ranked 99th out of 111 countries

- Transparency International: Corruption Perceptions Index 2005, ranked 88th out of 158 countries

- United Nations Development Programme: Human Development Index 2005, ranked 116th out of 177 countries

- World Economic Forum: Global Competitiveness Report 2005-2006 - Growth Competitiveness Index Ranking, ranked 82nd out of 117 countries

- World Bank: Doing Business 2006, ranked 83rd out of 155

- World Bank: Ease of Starting a Business 2006, ranked 69th out of 155

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development: Foreign Direct Investment Performance Index 2004, ranked 35th out of 140

| Geographic locale |

|

Template:Administrative divisions of Moldova Countries of Europe

Albania · Andorra · Armenia2 · Austria · Azerbaijan1 · Belarus · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Croatia · Cyprus2 · Czech Republic · Denmark3 · Estonia · Finland · France3 · Georgia1 · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Kazakhstan1 · Latvia · Liechtenstein · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Republic of Macedonia · Malta · Moldova · Monaco · Montenegro · Netherlands3 · Norway3 · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia1 · San Marino · Serbia · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain3 · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey1 · Ukraine · United Kingdom3 · Vatican City 1 Has majority of its territory in Asia. 2 Entirely in Asia but having socio-political connections with Europe. 3 Has dependencies or similar territories outside Europe. |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.