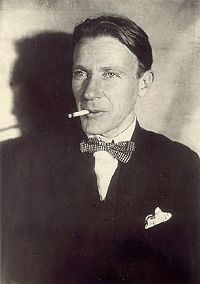

Mikhail Bulgakov

Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov (or Bulhakov, Михаил Афанасьевич Булгаков; May 15 (May 3 Old Style), 1891 – March 10, 1940) was a Soviet novelist and playwright of the first half of the 20th century. Although a native of Kiev, he wrote in Russian. Like his Ukrainian predecessor, Nikolai Gogol, he was a humorist and satirist of the first order. The object of his sharp wit was the Soviet regime and particularly the "homo Sovieticus," or new Soviet man that the regime was seeking to create. Bulgakov exposed the futility of this attempt to re-engineer human souls in his novellas, like Fatal Eggs and Heart of a Dog, and in his greatest work by far and one of the greatest novels written in the Soviet period, The Master and Margarita.

Biography

Mikhail Bulgakov was born in Kiev, Ukraine, the oldest son of a professor at Kiev Theological Academy. In 1913 Bulgakov married Tatiana Lappa. In 1916, he graduated from the Medical School of Kiev University. The Bulgakov sons enlisted in the White Army during the Civil War. All but Mikhail would up in Paris at the war's conclusion. Mikhail graduated from Kiev Univesity with a degree in medicine, enlisting as a field doctor. He ended up in the Caucasus, where he eventually began working as a journalist. In 1921, he moved with Tatiana to Moscow where he stayed for the rest of his life. Three years later, divorced from his first wife, he married Lyubov' Belozerskaya. In 1932, Bulgakov married for the third time, to Yelena Shilovskaya, and settled with her at Patriarch's Ponds. During the last decade of his life, Bulgakov continued to work on The Master and Margarita, wrote plays, critical works, stories, and made several translations and dramatizations of novels.

Despite his relatively favored status under the Soviet regime of Joseph Stalin, Bulgakov was prevented from either emigrating or visiting his brothers in the West. Bulgakov never supported the regime, and mocked it in many of his works, most of which were consigned to his desk drawer for several decades because they were too politically sensitive to publish. In 1938 he wrote a letter to Stalin requesting permission to emigrate and received a personal phone call from Stalin himself denying his request. Bulgakov died from an inherited kidney disorder in 1940 and was buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

Early works

During his life, Bulgakov was best known for the plays he contributed to Konstantin Stanislavsky's Moscow Art Theater. They say that Stalin was fond of the play Days of the Turbins (Дни Турбиных), which was based on Bulgakov's phantasmagoric novel The White Guard. His dramatization of Moliere's life in The Cabal of Hypocrites is still run by the Moscow Art Theater. Even after his plays were banned from the theaters, Bulgakov wrote a grotesquely funny comedy about Ivan the Terrible's visit into 1930s Moscow and several plays about the young years of Stalin. This perhaps saved his life in the year of terror 1937, when nearly all writers who did not support the leadership of Stalin were purged.

Bulgakov started writing prose in the early 1920s, when he published autobiographical works, such as The White Guard and a short story collection entitled Notes of a Country Doctor, both based on Bulgakov's experiences in post-revolutionary Ukraine. In the mid-1920s, he came to admire the works of H.G. Wells and wrote several stories with sci-fi elements, notably The Fatal Eggs (1924) and the Heart of a Dog (1925).

Fatal Eggs and Heart of a Dog

The Fatal Eggs, a short story inspired by the works of H.G. Wells, tells of the events of a Professor Persikov, who in experimentation with eggs, discovers a red ray that accelerates growth in living organisms. At the time, an illness passes through the chickens of Moscow, killing most of them. To remedy the situation, the Soviet government puts the ray into use at a farm. Unfortunately there is a mix up in egg shipments and the Professor ends up with the chicken eggs, while the government-run farm receives a shipment of the eggs of ostriches, snakes and crocodiles that were meant to go to the Professor. The mistake is not discovered until the eggs produce giant monstrosities that wreak havoc in the suburbs of Moscow, killing most of the workers on the farm. The propaganda machine then turns onto Persikov, distorting his nature in the same way his "innocent" tampering created the monsters. This satire of the bungling bureaucracy earned Bulgakov the reputation as a counter-revolutionary.

Heart of a Dog, a story obviously based on Frankenstein, features a professor who implants human testicles and pituitary gland into a dog named Sharik. The dog then proceeds to become more and more human as time passes, but his brutish manner results in all manner of chaos. The tale is clearly a critical satire on the Soviet "new man." It was turned into a comic opera called The Murder of Comrade Sharik by William Bergsma in 1973. A hugely popular screen version of the story followed in 1988.

The Master and Margarita

The Master and Margarita (Russian: Мастер и Маргарита) is one of the greatest Russian novels of the 20th century – and one of the most humorous.

History

Bulgakov started writing his most famous and critically acclaimed novel in 1928. The first version of the novel was destroyed (according to Bulgakov, burned in a stove) in March 1930 when he was notified that his piece Cabal of Sanctimonious Hypocrites (Кабала святош) was banned. The work was restarted in 1931 and the second draft was completed in 1936 by which point all the major plot lines of the final version were in place. The third draft was finished in 1937. Bulgakov continued to polish the work with the aid of his wife, but was forced to stop work on the fourth version four weeks before his death in 1940. The work was completed by his wife during 1940-1941.

A censored version (12% of the text removed and still more changed) of the book was first published in Moscow magazine (no. 11, 1966 and no. 1, 1967). The text of all the omitted and changed parts, with indications of the places of modification, was published insamizdat, or self-publication. In 1967 the publisher Posev (Frankfurt) printed a version produced with the aid of these modifications. In Russia, the first complete version, prepared by Anna Saakyants, was published by Khudozhestvennaya Literatura in 1973, based on the version of the beginning of 1940 proofread by the publisher. This version remained the canonical edition until 1989, when the last version was prepared by literature expert Lidiya Yanovskaya based on all available manuscripts.

The novel: settings, themes and narrative style

The novel alternates between three settings. The first is 1930s Moscow, which is visited by Satan in the guise of Woland (Воланд), a mysterious gentleman "magician" of uncertain origin, who arrives with a retinue that includes a grotesquely dressed "ex-choirmaster" valet Fagotto (Фагот, the name means "bassoon" in Russian and some other languages) , a mischievous, gun-happy, fast-talking black cat Behemoth (Бегемот, a subversive Puss in Boots), a fanged hitman Azazello (Азазелло, a hint to Azazel), a pale-faced Abadonna (Абадонна, an allusion to Abbadon) with a death-inflicting stare and a witch Gella (Гелла). The havoc wreaked by this group targets the literary elite, along with its trade union, MASSOLIT, its privileged HQ-cum-restaurant Griboyedov's House, corrupt social-climbers and their women (wives and mistresses alike) – bureaucrats and profiteers – and, more generally, skeptical unbelievers in the human spirit, as Bulgakov understands it. The dazzling opening fanfare of the book, a comic tour-de-force, presents a head-on/head-off collision between the unbelieving head of the literary bureaucracy, Berlioz (Берлиоз), and an urbane foreign gentleman who defends belief and reveals his prophetic powers (Woland). This is witnessed by a young and enthusiastically modern poet, Ivan Bezdomny (Иван Бездомный, the name means "Homeless"), whose gradual conversion from "modern" to "traditional" and rejection of literature (shades of Tolstoy and Sartre!) provides a unifying narrative and ideological development curve in the novel. In one of its facets the book is a Bildungsroman with Ivan as its focus. His futile attempt to chase and capture the "gang" and warn of their evil and mysterious nature both leads the reader to other central scenes and lands Ivan himself in a lunatic asylum. Here we are introduced to The Master, a bitter author, the petty-minded rejection of whose historical novel about Pontius Pilate and Christ has led him to such despair that he burns his manuscript and turns his back on the "real" world including his devoted lover, Margarita (Маргарита). Major episodes in the first part of the novel include another comic masterpiece – Satan's show at the Variety, satirizing the vanity, greed and gullibility of the new rich – and the capture and occupation of Berlioz's flat by Woland and his gang.

Eventually, in Part 2, we finally meet Margarita, the Master's mistress, who represents human passion and refuses to despair of her lover or his work. She is made an offer by Satan, and accepts it, becoming a witch with supernatural powers on the night of his Midnight Ball, or Walpurgis Night, which coincides with the night of Good Friday, linking all three elements of the book together, since the Master's novel also deals with this same spring full moon when Christ's fate is sealed by Pontius Pilate and he is crucified in Jerusalem.

The second setting is the Jerusalem of Pontius Pilate, described by Woland talking to Berlioz ("I was there") and echoed in the pages of the Master's rejected novel, which concerns Pontius Pilate's meeting with Yeshua Ha-Notsri (Jesus), his recognition of an affinity with and spiritual need for him, and his reluctant but resigned and passive handing over of him to those who want to kill him. There is a complex relationship between Jerusalem and Moscow throughout the novel, sometimes polyphony, sometimes counterpoint. The themes of cowardice, trust, treachery, intellectual openness and curiosity, and redemption are prominent.

The third setting is the one to which Margarita provides a bridge. Learning to fly and control her unleashed passions (not without exacting violent retribution on the literary bureaucrats who condemned her beloved to despair), and taking her enthusiastic maid Natasha with her, she enters naked into the world of the night, flies over the deep forests and rivers of Mother Russia, bathes, and, cleansed, returns to Moscow as the anointed hostess for Satan's great Spring Ball. Standing by his side, she welcomes the dark celebrities of human history as they pour up from the opened maw of Hell.

She survives this ordeal without breaking, borne up by her unswerving love for the Master and her unflinching acknowledgment of darkness as part of human life. For her pains and her integrity, she is rewarded well. Satan's offer is extended to grant her her deepest wish. She chooses to liberate the Master and live in poverty and love with him. In an ironic ending, neither Satan nor God think this is any kind of life for good people, and the couple leave Moscow with the Devil, as its cupolas and windows burn in the setting sun of Easter Saturday.

The interplay of fire, water, destruction and other natural forces provides a constant accompaniment to the events of the novel, as do light and darkness, noise and silence, sun and moon, storms and tranquility, and other powerful polarities.

Ultimately, the novel deals with the interplay of good and evil, innocence and guilt, courage and cowardice, exploring such issues as the responsibility towards truth when authority would deny it, and the freedom of the spirit in an unfree world. Love and sensuality are dominant themes in the novel. Margarita's love for the Master leads her to leave her husband, but she emerges victorious, and doesn't end up under a train. Her spiritual union with the Master is also a sexual one. The novel is a riot of sensual impressions, but the emptiness of sensual gratification without love is illustrated time and again in the satirical passages. However, the stupidity of rejecting sensuality for the sake of empty respectability is also pilloried in the figure of the neighbour who becomes Natasha's hog-broomstick.

The novel is heavily influenced by Goethe's Faust. Part of its brilliance lies in the different levels on which it can be read, as hilarious slapstick, deep philosophical allegory, and biting socio-political satire critical of not just the Soviet system but also the superficiality and vanity of modern life in general – jazz is a favourite target, ambivalent like so much else in the book in the fascination and revulsion with which it is presented. But the novel is also full of modern amenities like the model asylum, radio, street and shopping lights, cars, lorries, trams, and air travel. There is little evident nostalgia for any "good old days" – in fact, the only figure in the book to even mention Tsarist Russia is Satan himself.

The narrative is brilliant in that Bulgakov employs entirely different writing styles in the alternating sections. The Moscow chapters, ostensibly involving the more "real and immediate" world, are written in a fast-paced, almost farcical tone, while the Jerusalem chapters – the words of the Master's fiction – are written in a hyper-realistic style. (See Mikhail Bulgakov for the impact of the novel on other writers.) The tone of the narrative swings freely from Soviet bureaucratic jargon to the visual impact of film noir, from sarcastic to deadpan to lyrical, as the scenes dictate. Sometimes the presentation is like an omniscient voice-over, sometimes in-your-face action. Dozens of characters are in focus at various times (a Russian nod to the collective spirit that Tolstoy would salute), and the memorable figures are memorable for their significance rather than the space they occupy in the novel. It is fast-moving and shamelessly scenic – filmic through and through. It even employs some macabre horror elements.

The book was never completed, and the final chapters are late drafts that Bulgakov pasted to the back of his manuscript. This draft status is barely noticeable to the casual reader, except perhaps in the very last chapter, which reads like notes of the way the main characters lived on in the author's imagination. It would probably be included in a dvd as extra material these days.

Bulgakov's old flat, in which parts of the novel are set, since 1980s has become a target for Moscow-based Satanist groups, as well as of Bulgakov's fans, and defaced with various kinds of graffiti. The building's residents, in an attempt to deter these groups, are currently attempting to turn the flat into a museum of Bulgakov's life and works. Unfortunately, they are having trouble contacting the flat's anonymous owner.

Art and women in the novel

The bitterest ironies of the book emerge if we consider Shelley's remark in the Defense of Poetry that "poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world". As a poet/writer, the Master is so unacknowledged that he feels more at home in a lunatic asylum than in society, at the mercy of the actual legislators of the world. But the whole novel is directed at demonstrating to the corrupt philistines in power that they are less in control than they might wish. Above all they have no control over death or the spirit. They might mobilize the forces of darkness themselves, but fall short in a face-to-face contest with the Prince of Darkness. It is notable that Bulgakov attacks no actual political leaders. His targets are all minions of one kind or another, albeit comfortably placed minions, like Berlioz, the head of Massolit, the literary bureaucracy. Despite the grand gestures of universality – darkness and light, the world and the stars, historical and geographical range – the novel is to a great extent a psycho-drama playing itself out in the literary world. The protagonists are the Academy and Bohemia. Even Pilate and Christ clash on these terms of authority vs authenticity. Bulgakov induces a "willing suspension of disbelief" almost as effective as the tricks pulled off in the Variety by Woland, Fagotto the valet and Behemoth the cat. Georg Lukacs's remarks on naturalism in his critical work apply powerfully to this novel, too – focus on either the close-up surface texture of society, or the distant mystery of the stars at night. Treating the doings of a narrow circle as affairs of universal significance, and so on. No balanced middle ground. Bulgakov has all this.

And this affects his portrayal of women, too. Natasha seeks her freedom in witchdom, and Margarita flees respectability to devote herself to the service of her lover. She saves him, as Gretchen saves Faust, but likewise only because of the heroic challenge he has mounted to the "peace of the graveyard". "Das ewig Weibliche zieht uns hinan", Goethe wrote – "the eternal feminine draws us onward" – and the feeling is the same in The Master and Margarita. Most of the other female characters in the book are wives or mistresses of males in positions with some social clout. Or unattractive biddies.

Of course, this courtly idealism with regard to women and relationships (and the ethos of the Middle Ages forms a clear motif in the book, especially in the internal relations of Satan's team) is nothing new in Russian or European literature. What is a little surprising is that such a traditional portrayal of a woman's role is so skilfully presented that the novel achieved cult status and still enjoys it to some extent, first in the Soviet Union and now in the Russian Federation.

English translations

There are four published English translations of The Master and Margarita:

- Mirra Ginsburg (Grove Press, 1967)

- Michael Glenny (Harper & Row, 1967)

- Diana Burgin and Katherine Tiernan O'Connor (Ardis, 1995)

- Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (Penguin, 1997)

Ginsburg's translation was from a censored Soviet text and is therefore incomplete. While opinions vary over the literary merits of the different translations and none of them can be considered perfect, the latter two are generally viewed as being more faithful to the nuances of the original.

Glenny's translation runs more smoothly than that of Pevear and Volokhonsky, but is very cavalier with the text, whereas Pevear and Volokhonsky pay for their attempted closeness by losing idiomatic flow. A close examination of almost any paragraph of the novel in these two versions in comparison with the original reveals shortcomings and glaring discrepancies, however.

Influence

Various authors and musicians have credited The Master and Margarita as inspiration for certain works. Salman Rushdie's novel The Satanic Verses, for example, clearly was influenced by Bulgakov's masterwork.

The Rolling Stones have said the novel was key in their song "Sympathy for the Devil". The grunge band Pearl Jam were influenced by the novel's confrontation between Yeshua Ha-Notsri, that is, Jesus, and Pontius Pilate for their 1998 "Yield" album song, "Pilate". The Lawrence Arms based their album The Greatest Story Ever Told on the book and several of its themes. The Franz Ferdinand song "Love and Destroy" was based on a scene where Margarita flies over Moscow on her way to the Walpurgis Night Ball.

It is the fantasy satirical novel The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита), written in the 1930s, but published in 1967 by his wife, almost thirty years after his death, that has granted him critical immortality. The book was available underground, as samizdat, for many years in the Soviet Union, before the serialization of a censored version in the journal Moskva, and in a more complete version in the West. In the opinion of many, The Master and Margarita is the best of the Soviet novels, although it had to wait until after the thaw to be officially published.

The action of the novel takes place in several different locations and at several different levels. The backdrop is 1930s Stalinist Soviet society. It is a portrayed as a place of graft, corruption and moral cowardice. Its pedestrian banality is shaken when the Devil shows up with an ensemble of petty demons, including a remarkable talking black cat. These quite literally "diabolical forces" turn the world upside down, exposing the greed and hypocrisy of the good citizens of Moscow's elite in an hysterical fashion. In sharp contrast to that story is the poignant retelling of the story of Yeshua and Pontius Pilate in selections from a novel by the "Master." The juxtaposition of that story with the hysterical shenanigans of the Devil and his associates in 1930s Moscow only serves to highlight the satical depiction of the contemporary Soviet society. Finally, to this Hoffmanesque fantasmagoria is added a science fiction element, a metaphysical flight from the bleak present and the poignant past into a hopeful future region where a utopian place can be reached.

The novel contributed a number of Orwellian sayings to the Russian language, for example, "Manuscripts don't burn". A destroyed manuscript of the Master is an important element of the plot, but also refers to the fact that Bulgakov rewrote the entire novel from memory after he burned the first draft manuscript with his own hands.

Famous quotes

- "Manuscripts do not burn" ("Рукописи не горят") — The Master and Margarita

- "Second-grade fresh" — The Master and Margarita

Bibliography

Short stories

- Notes on Cuffs (Записки на манжетах)

- Notes of a Country Doctor (Записки юного врача)

- Fatal Eggs (Роковые яйца)

- Heart of a Dog (Собачье сердце)

Plays

- Days of the Turbins (Дни Турбиных) — one family's survival in Kiev during the Russian Civil War

- Flight (play) (Бег) — satirizing the flight of White emigrants to the West

- Ivan Vasilievich (Иван Васильевич) — Ivan the Terrible brought by the Time Machine to a crowded apartment in the 1930s Moscow

- The Cabal of Hypocrites (Кабала святош) — Moliere's relations with Louis XIV's court

- Pushkin (The Last Days) (Пушкин) — the last days of the great Russian poet

- Batum (Батум) — Stalin's early years in Batumi

Novels

- The White Guard (Белая гвардия)

- Life of Monsieur de Molière (Жизнь господина де Мольера)

- Black Snow, or the Theatrical Novel (Театральный роман)

- The Master and Margarita (Мастер и Маргарита)

External links

- Bulgakov's Master and Margarita

- Mikhail Bulgakov

- Bulgakov.ru — amateur but very high-quality site, devoted solely to Bulgakov and his works (in Russian)

- Mikhail Bulgakov — three languages site (German, English and Russian)

- Bulgakov Project (in Russian)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.