Mastodon

| Mastodon | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mounted Mammut americanum skeleton. Mounted Mammut americanum skeleton.

| ||||||||||||

|

Prehistoric

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

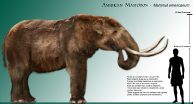

Mastodon is the common name for any of the large, extinct elephant-like mammals comprising the family Mammutidae (syn. Mastodontidae) of the order Proboscidea, characterized by long tusks, large pillar-like legs, and a flexible trunk, or proboscis. Although similar to elephants (family Elephantidae, including mammoths, mastodons belong to a different family of proboscidians, and have molar teeth of a different structure. They also are known as mastodonts.

Mastodons lived from about the Oligocene of the Paleogene period, about 30 million years ago, until about 10,000 years ago, when the only known North American species, the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) died out. This well-known species is a close relative of the Borson's mastodon (Mammut borsoni) that lived in Europe.

The name comes from the Greek μαστός and οδούς, meaning "nipple tooth," reflecting the distinctive, cone-like cusps or nipple-like protrusions on the crowns, which would have been more conducive to browsing on trees, shrubs, and swamp plants than grazing on grasses as with the mammoths and their flatter, ridged teeth (Dykens and Gillette, BBC).

Overview and description

Mastodons belong to the mammalian order Proboscidea. Today, only the elephant family, Elephantidae, includes extant (living) species. Mastodons belong to another proboscidean family, Mammutidae (syn. Mastodontidae). The mammoths are another extinct group that overlapped in time with the mastodons, also dying out about 10,000 years ago, but they also belonged to the Elephantidae family, as the genus Mammuthus. Altogether, paleontologists have identified about 170 fossil species that are classified as belonging to the Proboscidea, with the oldest dating from the early Paleocene epoch of the Paleogene period over 56 million years ago.

Mastodons, like elephants, are large, heavy mammals with tusks and flexible tusks. Their skulls tended to be larger than those of mammoths, and the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) has low-domed heads unlike the higher-domed heads of mammoths and modern-day Asian elephants (Dykens and Gillette). The skeleton of mastodons was stockier and more robust (Kurtén and Anderson 1980, p. 345). Mastodons also seem to have lacked the undercoat characteristic of mammoths (Kurtén and Anderson 1980, p. 345).

Mastodons differed from mammoths primarily in the blunt, conical, nipple-like projections on the crowns of their molars, which were more suited to chewing leaves than the high-crowned teeth mammoths used for grazing. Thus, the name mastodon, which means "nipple teeth," became both their common name and an obsolete name for their family and genus (Agusti and Mauricio 2002). In contrast, mammoths, and elephants, whose molars were large, complex, specialized structures, had molars that were more flat and had low ridges of dense enamel on the surface (ANS). Mastodons are thought to have been browsers, while mammoths were grazers.

The American mastodon tended to be about 2.1 meters (7 feet) in height for females and 3.1 meters (10 feet) in height for the males, with adult mastodons weighing as much as 5500 kilograms (6 tons)(Dykens and Gillette). This is smaller than the imperial mammoth of North America, which reached great size, being up to at least 5 meterss (16 feet) at the shoulder (ANS). It also is smaller than the largest group of extant elephants, the African elephants, which are up to 3.9 meters (13 feet) tall. It is about the size of woolly mammoths, which had about the same height (2.8 to 3.4 meters, or 9 to 11 feet) and weight (4 to 6 tons) as the Asian elephants (ANSP).

Mastodon tusks tended to be less curved than mammoths, but longer and larger than those of modern elephans (Dykens and Gillette). The tusks of the American mastodon sometimes exceeded five meters in length and were nearly horizontal, in contrast with the more curved mammoth tusks (Kurtén and Anderson 1980). Young males had vestigial lower tusks that were lost in adulthood (Kurtén and Anderson 1980). However, it has been proven that female American mastodons had lower pairs of tusks.

The tusks of American mastodons were probably used to break branches and twigs, although some evidence suggests males may have used them in mating challenges; one tusk is often shorter than the other, suggesting that, like humans and modern elephants, mastodons may have had laterality (Kurtén and Anderson 1980). Examination of fossilized tusks revealed a series of regularly spaced shallow pits on the underside of the tusks. Microscopic examination showed damage to the dentin under the pits. It is theorized that the damage was caused when the males were fighting over mating rights. The curved shape of the tusks would have forced them downward with each blow, causing damage to the newly forming ivory at the base of the tusk. The regularity of the damage in the growth patterns of the tusks indicates that this was an annual occurrence, probably occurring during the spring and early summer (Fisher 2006).

Distribution and habitat

Fossils of the American mastodon (Mammut americanum) have been found across all of the North America, from Alaska to central Mexico, and on the eastern seaboard (Dykens and Gillette). Other species of mastodon were widely distributed throughout the world, with fossils found common and well-preserved in Pliocene and Pleistocene age deposits.

Mastodons are thought to have first appeared almost four million years ago. They were native to both Eurasia and North America but the Eurasian species Mammut borsoni died out approximately three million years ago - fossils having been found in England, Germany, the Netherlands and northern Greece. Mammut americanum disappeared from North America about 10,000 years ago,[1] at the same time as most other Pleistocene megafauna.

Though their habitat spanned a large territory, mastodons were most common in the ice age spruce forests of the eastern United States, as well as in warmer lowland environments.[2] Their remains have been found as far as 300 kilometers offshore of the northeastern United States, in areas that were dry land during the low sea level stand of the last ice age.[3] Mastodon fossils have been found in South America; on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state, USA (Manis Mastodon Site);[4] in Kentucky (particularly noteworthy are early finds in what is now Big Bone Lick State Park); the Kimmswick Bone Bed in Missouri; in Stewiacke, Nova Scotia, Canada; in Richland County, Wisconsin; La Grange, Texas; and north of Fort Wayne, Indiana, USA.

Appearance and extinction

Mastodons first appear in Northern Africa in the Oligocene of the Paleogene period about 30 million years ago, while Primelephas, the ancestor of mammoths and modern elephants, appeared in the late Miocene epoch, about 7 million years ago.

Recent studies indicate that tuberculosis may have been partly responsible for the extinction of the mastodon 10,000 years ago.[5]

Another influencing factor to their eventual extinction in America during the late Pleistocene may have been the presence of Paleo-indians, which entered the American contient in relatively large numbers 13,000 years ago. Their hunting caused a gradual attrition to the Mastodon and Mammoth populations, siginificant enough that over time the Mastodons were hunted to extinction.[6]

In September 2007, Mark Holley, an underwater archeologist with the Grand Traverse Bay Underwater Preserve Council who teaches at Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City, Michigan, said that they might have discovered a boulder (3.5 to 4 feet high x 5 feet long) with a prehistoric carving in the Grand Traverse Bay of Lake Michigan. The granite rock has markings that resemble a mastodon with a spear in its side. Confirmation that the markings are an ancient petroglyph will require more evidence.[7]

Current excavations

Current excavations are going on annually at the Hiscock site in Byron, New York, for mastodon and related paleo-Indian artifacts. The site was discovered in 1959 by the Hiscock family while digging a pond with a backhoe; they found a large tusk and stopped digging. The Buffalo Museum of Science has organized the dig since 1983. It has been called one of the richest sites available for mastodon-related artifacts. The site sits on swampland that was covered by Lake Tonowanda, which was a glacier runoff lake formed over 10,000 years ago. It has been confirmed that mastodons would flock there to eat the sodium-rich clay during one of the last great droughts of the paleolithic.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ "Greek mastodon find 'spectacular'", BBC News, 24 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ Björn Kurtén and Elaine Anderson, Pleistocene Mammals of North America, (New York: Columbia UP, 1980), p. 344.

- ↑ Kurtén and Anderson, p. 344.

- ↑ Kirk and Daugherty, Archaeology in Washington, forthcoming from University of Washington Press, April 2007.

- ↑ Mastodons Driven to Extinction by Tuberculosis, Fossils Suggest

- ↑ Ward, Peter, "The Call of Distant Mammoths", 1997.

- ↑ Flesher, John, "Possible mastodon carving found on rock", Associated Press, 2007-09-04. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia (ANSP). n.d. American mastodon (Mammut americana). Academy of Natural Sciences. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

.[1]

- British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). n.d. American mastodon, Mammut americanum. BBC. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Dykens, M., and L. Gillette. n.d. Mammut americanum American mastodon. San Diego History Museum. Retrieved May 16, 2008.

- Björn Kurtén and Elaine Anderson, Pleistocene Mammals of North America, (New York: Columbia UP, 1980), p. 344.

External links

- http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/larson/mammut.html

- http://www.calvin.edu/academic/geology/mastodon/calvin_c.htm

- http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/expeditions/treasure_fossil/Treasures/Warren_Mastodon/warren.html?acts

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/3004.shtml

- Greek Mastadon find 'spectacular' (BBC)

- http://www.priweb.org/mastodon/mastodon_home.html

- http://www.mostateparks.com/mastodon.htm

- http://www.slfp.com/Mastodon.htm

- http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/exhibits

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Agusti, Jordi & Anton, Mauricio (2002). Mammoths, Sabretooths, and Hominids. New York: Columbia University Press, 106. ISBN 0-231-11640-3.

- ↑ Fisher, D (Oct. 18-21, 2006). "Tusk cementum defects record musth battles in American mastodons". Sixty-Sixth Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.