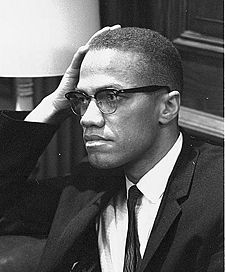

Malcolm X

| Malcolm X |

|---|

| Born |

| May 19, 1925 Omaha, Nebraska, USA |

| Died |

| February 21, 1965 New York, New York, USA |

- This article is about Malcolm X the man. For the biographical movie of the same name, see Malcolm X (film).

Malcolm X (May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965). Birth name: Malcolm Little. Later nicknamed, Detroit Red. Later Islamic names: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz and Omowale. He was a Muslim Minister and a National Spokesman for the Nation of Islam. He was also founder of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. and of the Organization of Afro-American Unity.

Introduction

As the United States entered the year 1920, the raging debate over whether the races should be separated or integrated became more and more sharply focused within the public consciousness. The debate was, of course, hottest within the black community. The preceding decade had seen at least 527 (reported) lynchings of American blacks, including the particularly sadistic and barbaric 1918 lynching of the pregnant Mary Turner, in Valdosta, Georgia. In addition, during that decade, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had been incorporated in New York; the administration of Democrat President Woodrow Wilson had made it clear that, regarding the Chief Executive's guarantee of "fair and just treatment for all," the word "all" meant "whites only."; the nation had experienced no fewer than thirty-three major race riots; the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) had received a charter from the Superior Court of Fulton County, Georgia; and Booker T. Washington had passed away in 1915.

America's race crisis was a boiling cauldron, and the entire world was witness to American Christianity's failure to penetrate the culture and make real the tenets of Jesus's teachings on the love of God and the oneness of the Body of Christ. Fifty-seven years had passed since the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation. And despite the climate of racial hatred, blacks—now 9.9 per cent of the total population—were making real economic gains. By 1920, there were at least 74,400 blacks in business and/or business-related professions. Black America had more than $1 billion accumulated, and the self-help drive was being stronly led by Marcus Garvey and his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA).

In the midst of the segregation-integration debate, the black masses struggled daily for the cause of economic independence, coupled with solidarity and group uplift. Into this mix of interior activism and nationalist sentiment was born Malcolm X, whose voice would later articulately ring out on behalf of the voiceless—on behalf of those blacks of the streets and ghettos who were most alienated from the ideals of cultural assimilation and social integration. His would be a message that would position itself as the categorical antipode to the doctrine of nonviolent protest and belief in an integrated America that hallmarked the ministry of Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.

Biography

Malcolm Little was born in Omaha, Nebraska to Earl Little and Louise Norton. His father was an outspoken Baptist lay preacher and supporter of Marcus Garvey, as well as a member of the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Malcolm described his father as a big black man who had lost one eye. Three of Earl Little's brothers died violently at the hands of white men, one of whom was lynched. Earl Little had three children by a previous marriage before he married Malcolm's mother. From his second marriage he had eight children of which Malcolm was the fifth.

Louise Little was born in Grenada and, according to Malcolm, she looked more like a white woman. Her father was a white man of whom Malcolm knew nothing except his mother's shame. Malcolm got his light complexion from him. Initially he felt it was a status symbol to be light-skinned but later he would say that he “hated every drop of that white rapist's blood that is in me.” As Malcolm was the lightest child in the family, he felt that his father favored him; however, his mother gave him more hell for the same reason.[1]

According to Malcolm X's autobiography, his mother had been threatened by Ku Klux Klansmen while she was pregnant with him in December of 1924; his mother recalled that the family was warned to leave Omaha, because his father's involvement with UNIA was, according to the Klansmen, "stirring up trouble".[1]

After Malcolm was born, the family relocated to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1926, and then to Lansing, Michigan shortly thereafter. In 1931 his father was found dead having been run over by a streetcar in Michigan. Authorities ruled his death suicide[2]. This cause of death was disputed by the African American community at the time, and later by Malcolm himself, as Malcolm's family had frequently found themselves the target of harassment by the white-supremacist Black Legion, which had already culminated in the burning down of their home in 1929.[3] . Malcolm wondered how his father could bash himself in the head and then lay down across street tracks to get run over[2].

Though Malcolm’s father had two life insurance policies, his mother was paid from only the smaller policy. The insurance company for the larger policy refused to pay, claiming Earl Little's death was by suicide[3]. The financial and emotional stress of rearing eight children by herself caused Louise Little to succumb to a mental breakdown, and she was declared legally insane in December 1938. Malcolm and his siblings were split up and sent to different foster homes. Louise Little was formally committed to the State Mental Hospital at Kalamazoo, Michigan, and remained there until Malcolm and his brothers and sisters were able to get her released twenty-six years later.

The Autobiography of Malcolm X and local folklore held that, following the death of his father, he lived as a boy on Charles Street in downtown East Lansing. However, the 1930 U.S. Census (released in 2002) shows him living on a completely different Charles Street, in the low-income Urbandale neighborhood in Lansing Township, between Lansing and East Lansing. Later, at the time he was in high school, he lived in Mason, an almost all-white small town twelve miles to the south.

Malcolm graduated from junior high school at the top of his class, but dropped out soon after an admired teacher told him that his aspirations of being a lawyer were "no realistic goal for a nigger"[4]. After enduring a series of foster homes, Malcolm was first sent to a detention center and then later moved to Boston to live with his older half-sister, Ella Little Collins.

He found work as a shoe-shiner at a Lindy Hop nightclub; in his autobiography, he says that he once shined the shoes of Duke Ellington and other notable black musicians. He was also employed for a time by New Haven Railroad, a job he would maintain when he relocated to New York City in 1943.[4] After some time, in Harlem, he became involved in drug dealing, gambling, racketeering, and robbery (referred to collectively by Malcolm as "hustling"). When he was examined for the World War II draft, military physicians classified him to be "mentally disqualified for military service." He explains in his autobiography that putting on a display to avoid the draft, he told the examining officer that he couldn't wait to get his hands on a gun so he could "kill some crackers". His approach worked, and he was given a classification that ensured he would not be drafted.

In early 1946 he was arrested for a series of burglaries and received a sentence of 10 years. While in prison he received correspondence from his brother Reginald telling him about the Nation of Islam, to which he subsequently converted. While in prison he read voraciously and developed astigmatism. He was in regular contact with Elijah Muhammad during his incarceration and went to work for the Nation of Islam after his parole.

Nation of Islam

In 1952, after his release from prison, Malcolm went to meet Elijah Muhammad in Chicago. It was soon after this that he changed his surname to "X". Malcolm explained the name by saying, The "X" is meant to symbolize the rejection of "slave-names" and the absence of an inherited African name to take its place. The "X" is also the brand that many slaves received on their upper arm. This rationale made many members of the Nation of Islam change their surnames to X.

In March of 1953 the Federal Bureau of Investigation opened a file on Malcolm, supposedly in response to an allegation that he had described himself as a Communist; according to the Church Committee, the FBI had long been used to monitor, disrupt, and repress radicals like Malcolm. Included in the file were two letters wherein Malcolm uses the alias "Malachi Shabazz". In "Message To The Black Man In America", Elijah Muhammad explained the name Shabazz as belonging to descendants of an "Asian Black nation".

In May of 1953 the FBI concluded that Malcolm X had an "asocial personality with paranoid trends (pre-psychotic paranoid schizophrenia)", and had in fact, sought treatment for his disorder. This was further supported by a letter intercepted by the FBI, dated June 29, 1950. The letter said, in reference to his 4-F classification and rejection by the military, "Everyone has always said ... Malcolm is crazy, so it isn't hard to convince people that I am."[5]

Later that year, Malcolm left his half-sister Ella in Boston to stay with Elijah Muhammad in Chicago. He soon returned to Boston and became the Minister of the Nation of Islam's Temple Number Eleven.

In 1954, Malcolm X was selected to lead the Nation of Islam's mosque #7 on Lenox Avenue (co-named "Malcolm X Boulevard" in 1987, from 110th Street/Central Park North to 147th Street) in Harlem and he rapidly expanded its membership.

Malcolm X was a compelling public speaker, and was frequently sought after for quotations by the print media, radio, and television programs from around the world. In the years between his adoption of the Nation of Islam in 1952 and his split with the organization in 1964, he always espoused the Nation's teachings, including referring to whites as "devils" who had been created in a misguided breeding program by a black scientist, and predicting the inevitable (and imminent) return of blacks to their natural place at the top of the social order.

Malcolm X was soon seen as the second most influential leader of the movement, after Elijah Muhammad himself. He opened additional temples, including one in Philadelphia, and was largely credited with increasing membership in the NOI from 500 in 1952 to 30,000 in 1963. He inspired the boxer Cassius Clay to join the Nation of Islam and change his name to Muhammad Ali. (Like Malcolm X, Ali later left the NOI and joined mainstream Islam.)

Marriage

In 1958 Malcolm married Betty X (née Sanders) in Lansing, Michigan. They had six daughters together, all of whom carried the surname of Shabazz. Their names were Attallah (also spelled Attillah), born in 1958; Qubilah, born in 1960; Ilyasah, born in 1962; Gamilah (also spelled Gumilah), born in 1964; and twins, Malaak and Malikah, born after Malcolm's death in 1965.

Tensions

In the early 1960s, Malcolm was increasingly exposed to rumors of Elijah Muhammad's extramarital affairs with young secretaries. Adultery is condemned in the teachings of the Nation of Islam. At first, Malcolm brushed these rumors aside. Later he spoke with the women making the accusations and believed them. In 1963, Elijah Muhammad himself confirmed to Malcolm that the rumors were true, and claimed that this followed a pattern established by biblical prophets. Despite being unsatisfied with the excuses, and being disenchanted by other ministers using Nation of Islam funds to line their own pockets[citation needed], Malcolm's faith in Elijah Muhammad did not waver.

By the summer of 1963, tension in the Nation of Islam reached a boiling point. Malcolm believed that Elijah Muhammad was jealous of his popularity (as were several senior ministers). Malcolm viewed the March on Washington critically, unable to understand why black people were excited over a demonstration "run by whites in front of a statue of a president who has been dead for a hundred years and who didn't like us when he was alive." Later in the year, following the John F. Kennedy assassination, Malcolm delivered a speech as he regularly would. However, when asked to comment upon the assassination, he replied that it was a case of "chickens coming home to roost" — that the violence that Kennedy had failed to stop (and at times refused to rein in) had come around to claim his life. Most explosively, he then added that with his country origins, "Chickens coming home to roost never made me sad. It only made me glad." This comment led to widespread public outcry and led to the Nation of Islam's publicly censuring Malcolm X. Although retaining his post and rank as minister, he was banned from public speaking for ninety days by Elijah Muhammad himself. Malcolm obeyed and kept silent.

In the spring of 1963, Malcolm started collaborating on The Autobiography of Malcolm X with Alex Haley. He also publicly announced his break from the Nation of Islam on March 8, 1964 and the founding of the Muslim Mosque, Inc. on March 12, 1964. At this point, Malcolm mostly adhered to the teachings of the Nation of Islam, but began modifying them, explicitly advocating political and economic black nationalism as opposed to the NOI's exclusivist religious nationalism. In March and April, he made the series of famous speeches called "The Ballot or the Bullet" [citation needed]. Malcolm was in contact with several orthodox Muslims, who encouraged him to learn about orthodox Islam. He soon converted to orthodox Islam, and as a result decided to make his Hajj.

Hajj

On April 13, 1964, Malcolm departed JFK Airport, New York for Cairo by way of Frankfurt. It was the second time Malcolm had been to Africa. Malcolm left Cairo arriving in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia at about three in the morning. He was automatically suspect due to his inability to speak Arabic and his United States passport. He was separated from the group he came with and was isolated. He spent about 20 hours wearing the ihram, a two-piece garment comprised of two white unhemmed sheets—the first of which is worn draped over the torso and the second of which (the bottom) is secured by a belt.

It was at this time he remembered the book The Eternal Message of Muhammad by Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam and which Dr. Mahmoud Yousseff Sharwabi had presented to him with his visa approval. He called Azzam's son who arranged for his release. At the younger Azzam's home he met Azzam Pasha who gave Malcolm his suite at the Jeddah Palace Hotel. The next morning Muhammad Faisal, the son of Prince Faisal, visited and informed him that he was to be a state guest. The deputy chief of protocol accompanied Malcolm to the Hajj Court.

It therefore was a mere formality for Sheikh Muhammad Harkon to allow Malcolm to make his Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca). On April 19 he completed the Umrah, making the seven circuits around the Kaaba, drinking from the well of Zamzam and running between the hills of Safah and Marwah seven times.

The trip proved to be life-altering. Malcolm met many devout Muslims of a number of different races, whose faith and practice of Islam he came to respect. He believed that racial barriers could potentially be overcome, and that Islam was the one religion that conceivably could erase all racial problems.

A changed man

On May 21, 1964, he returned to the United States as a traditional Sunni Muslim (and with a new name — El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz).

When Malcolm returned to the United States, he gave a speech about his visit. This time he gave a much larger meaning and message than before. The speech was not only for the Muslims, instead it was for the whole nation and for all races. He said,

- "Human rights are something you were born with. Human rights are your God-given rights. Human rights are the rights that are recognized by all nations of this earth."

- "In the past, yes, I have made sweeping indictments of all white people. I will never be guilty of that again — as I know now that some white people are truly sincere, that some truly are capable of being brotherly toward a black man. The true Islam has shown me that a blanket indictment of all white people is as wrong as when whites make blanket indictments against blacks."

- "Since I learned the truth in Mecca my dearest friends have come to include all kinds — some Christians, Jews, Buddhists, Hindus, agnostics, and even atheists! I have friends who are called capitalists, socialists, and communists! Some of my friends are moderates, conservatives, extremists — some are even Uncle Toms! My friends today are black, brown, red, yellow, and white!" [5]

- "While in Mecca, for the first time in my life, I could call a man with blond hair and blue eyes my brother."

Along with A. Peter Bailey and others, El-Shabazz then founded the U. S. branch of the Organization of Afro-American Unity. Patterned after the Organization of African Unity (OAU), Africa's continental organization, which was established at Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in May 1963, the OAAU resolved to establish a non-religious and non-sectarian program for human rights. The OAAU included all people of African ancestry in the Western Hemisphere, as well as those on the African continent.

Africa

Malcolm X visited Africa on three separate occasions, once in 1959 and twice in 1964. During his visits, he met officials, as well as spoke on television and radio in: Cairo, Egypt; Addis Ababa, Ethiopia; Dar Es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania); Lagos and Ibadan, Nigeria; Accra, Winneba, and Legon, Ghana; Conakry, Guinea; Algiers, Algeria; and Casablanca, Morocco.

Malcolm first went to Africa in summer of 1959. He traveled to Egypt (United Arab Republic), Sudan, Nigeria and Ghana to arrange a tour for Elijah Muhammad, which occurred in December 1959. The first of Malcolm's two trips to Africa in 1964 lasted from April 13 until May 21. On May 8, following his speech at Trenchard Hall on the campus of the University of Ibadan in Nigeria, he attended a reception in the Students' Union Hall held for him by the Muslim Students' Society. During this reception the students bestowed upon him the name "Omowale" meaning "the son returns home" in the Yoruba language.

Malcolm returned to New York from Africa via Paris, France, on May 21, 1964. On July 9, he again left the United States for Africa, spending a total of 18 weeks abroad. On July 17, 1964, Malcolm addressed the Organization of African Unity's first ordinary assembly of heads of state and governments in Cairo as a representative of the OAAU. On August 21, 1964, he made a press statement on behalf of the OAAU regarding the second African summit conference of the OAU. In it, he explained how a strong and independent "United States of Africa" is a victory for the awakening of African Americans. By the time he returned to the United States on November 24, 1964, Malcolm had established an international connection between Africans on the continent and those in the diaspora.

Malcolm never changed his views that Black people in the U.S. were justified in defending themselves from their white aggressors. On June 28, 1964 at the founding rally of the OAAU he said, "The time for you and me to allow ourselves to be brutalized nonviolently has passed. Be nonviolent only with those who are nonviolent to you. And when you can bring me a nonviolent racist, bring me a nonviolent segregationist, then I'll get nonviolent. But don't teach me to be nonviolent until you teach some of those crackers to be nonviolent." [citation needed]

Increasingly though he did come to regret his involvement within the Nation of Islam and its tendency to promote racism as a blacks versus whites issue. In an interview with Gordon Parks in 1965 he revealed:

"I realized racism isn't just a black and white problem. It's brought bloodbaths to about every nation on earth at one time or another."

He stopped and remained silent for a few moments. "Brother," he said finally [to Gordon Parks], "remember the time that white college girl came into the restaurant — the one who wanted to help the Muslims and the whites get together — and I told her there wasn't a ghost of a chance and she went away crying?"

"Well, I've lived to regret that incident. In many parts of the African continent I saw white students helping black people. Something like this kills a lot of argument. I did many things as a [black] Muslim that I'm sorry for now. I was a zombie then — like all [black] Muslims — I was hypnotized, pointed in a certain direction and told to march. Well, I guess a man's entitled to make a fool of himself if he's ready to pay the cost. It cost me twelve years."

"That was a bad scene, brother. The sickness and madness of those days — I'm glad to be free of them."

Visiting the UK

On 12 February 1965 Malcolm X visited Smethwick, near Birmingham, which had become a byword for racial division after the 1964 general election when the Conservative Party won the parliamentary seat using the slogan, amongst others, "If you want a nigger for your neighbour, vote Labour" [6]. He visited a pub with a non-coloured policy, and purposely visited a street where the local council would buy houses and sell them to white families, to avoid black families moving in. He was accused of stirring up racial hatred in the area. [citation needed]

Assassination

On March 20, 1964, Life magazine published a famous photograph of Malcolm X holding an M1 Carbine and pulling back the curtains to peer out of a window. The photo was taken in connection with Malcolm's declaration that he would defend himself from the daily death threats which he and his family were receiving. Undercover FBI informants warned officials that Malcolm X had been marked for assassination. One officer undercover with the Nation of Islam is said to have reported that he had been ordered to help plant a bomb in Malcolm's car.

Tensions increased between Malcolm and the Nation of Islam. It was alleged that orders were given by leaders of the Nation of Islam to kill Malcolm; in The Autobiography of Malcolm X, he says that as early as 1963, a member of the Seventh Temple confessed to him having received orders from the Nation of Islam to kill him. The NOI sued to reclaim Malcolm's home in Queens, which they claimed to have paid for, and won. He appealed, and was angry at the thought that his family might soon have no place to live. Then, on the night of February 14, 1965, the house was firebombed. Malcolm and his family survived, and no one was charged in the crime.

A week later on February 21 in Manhattan's Audubon Ballroom, Malcolm had just begun delivering a speech when a disturbance broke out in the crowd of 400. A man yelled, "Get your hand outta my pocket! Don't be messin' with my pockets!" As Malcolm's bodyguards rushed forward to attend to the disturbance and Malcolm appealed for peace, a man rushed forward and shot Malcolm in the chest with a sawn-off shotgun. Two other men quickly charged towards the stage and fired handguns at Malcolm, who was shot 16 times. Angry onlookers in the crowd caught and beat the assassins as they attempted to flee the ballroom. The 39-year-old Malcolm was pronounced dead on arrival at New York's Columbia Presbyterian Hospital. He was killed by the shotgun blasts, the other bullets having been directed into his legs.

Although a police report once existed stating that two men were detained in connection with the shooting, that report disappeared, and the investigation was inconclusive. Two suspects were named by witnesses — Norman 3X Butler and Thomas 15X Johnson — however both were known as Nation of Islam agents and would have had difficulty entering the ballroom on that evening.

Three men were eventually charged in the case. Talmadge Hayer confessed to having fired shots into Malcolm's body, but he testified that Butler and Johnson were not present and were not involved in the shooting. All three were convicted.

A complete examination of the assassination and investigation is available in The Smoking Gun: The Malcolm X Files, a collection of primary sources relating to the assassination.

Funeral

Sixteen hundred people attended Malcolm's funeral in Harlem on February 27, 1965 at the Faith Temple Church of God in Christ (now Child's Memorial Temple Church of God in Christ). Ossie Davis, alongside Ahmed Osman, delivered a stirring eulogy, describing Malcolm as "Our shining black prince". Malcolm X was buried at the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. At the gravesite after the ceremony, friends took the shovels away from the waiting gravediggers and buried Malcolm themselves. Later that month, actress Ruby Dee and Sidney Poitier became co-chairs of the the New York affiliate of the Educational Fund for the Children of Malcolm X Shabazz. Civil rights leader and surgeon, T.R.M. Howard, was the chair of the Chicago affiliate of the Fund.

Quotations

- '"We declare our right on this earth to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary."' [citation needed]

- "The earth's most expensive and pernicious evil is racism, the inability of God's creatures to live as One, especially in the Western world." - The Autobiography of Malcolm X

- "You can’t drive a knife into a man’s back nine inches, pull it out six inches, and call it progress." [citation needed]

- "It is only after the deepest darkness that the greatest light can come; it is only after extreme grief that the greatest joy can come; it is only after slavery and prison that the greatest appreciation of freedom can come." - 1965 [citation needed]

- "The only true world solution today is governments guided by true religion - of the spirit." [citation needed]

- "Yes, I'm an extremist. The black race here in North America is in extremely bad condition. You show me a black man who isn't an extremist and I'll show you one who needs psychiatric attention!" —Cited in The Autobiography.

- "The young whites, and blacks, too, are the only hope that America has, the rest of us have always been living in a lie." —Quoted by Alex Haley, after a college campus speech, in the epilogue to The Autobiography.

- "The true Islam has shown me that a blanket indictment of all white people is as wrong as when whites make blanket indictments against blacks." [citation needed]

- "I've had enough of somebody else's propaganda. I'm for truth, no matter who tells it. I'm for justice, no matter who it is for or against. I'm a human being first and foremost, and as such I'm for whoever and whatever benefits humanity as a whole." —From "1965," The Autobiography.

- "You trust them (white Americans), and I don't. You studied what he wanted you to learn about him in schools. I studied him in the streets and in prison, where you see the truth." [citation needed]

- "I remember one night at Muzdalifa with nothing but the sky overhead, I lay awake amid sleeping Muslim brothers and I learned that pilgrims from every land - every colour, and class, and rank; high officials and the beggar alike - all snored in the same language." [citation needed]

- "America needs to understand Islam, because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem." —From a letter Malcolm X wrote to his wife and, concurrently, Muslim Mosque, Inc., toward the end of his pilgrimage to Mecca; cited in The Autobiography.

- "You're not to be so blind with patriotism that you can't face reality. Wrong is wrong, no matter who does it or says it." [citation needed]

- "Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone; but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery." — From Malcolm X Speaks.

- "Nobody can give you freedom. Nobody can give you equality or justice or anything. If you're a man, you take it." [citation needed]

- "They called me the 'angriest Negro in America'. I wouldn't deny that charge." [citation needed]

- "You can't separate peace from freedom because no one can be at peace unless he has his freedom." [citation needed]

- "How can anyone be against love?" [citation needed]

- "We want freedom by any means necessary. We want justice by any means necessary. We want equality by any means necessary." [citation needed]

- "Whites can help us, but they can't join us. There can be no black/white unity, until there is first some black unity." — From the press conference at which he announced the formation of Muslim Mosque, Inc.; cited in The Autobiography.

- "The price of freedom is death." -NYC, June 1964 [citation needed]

- "The only way we'll get freedom for ourselves is to identify ourselves with every oppressed people in the world. We are blood brothers to the people of Brazil, Venezuela, Haiti,...Cuba- yes, Cuba too." June 10, 1964. [citation needed]

- "If you're not ready to die for it, put the word 'freedom' out of your vocabulary." [citation needed]

- "Power in defense of freedom is greater than power in behalf of tyranny and oppression." [citation needed]

- "Anytime you beg another man to set you free, you will never be free. Freedom is something that you have to do for yourself." [citation needed]

- "I am a Muslim, because it's a religion that teaches you an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. It teaches you to respect everybody, and treat everybody right. But it also teaches you if someone steps on your toe, chop off their foot. And I carry my religious axe with me all the time." [citation needed]

- "I believe in human beings, and that all human beings should be respected as such, regardless of their color." [citation needed]

- "I believe in a religion that believes in freedom. Any time I have to accept a religion that won't let me fight a battle for my people, I say to hell with that religion." [citation needed]

- "A man who stands for nothing will fall for anything." [citation needed]

- "I want Dr. King to know that I didn't come to Selma to make his job difficult. I really did come thinking I could make it easier. If the white people realize what the alternative is, perhaps they will be more willing to hear Dr. King." [citation needed]

- "Concerning non-violence, it is criminal to teach a man not to defend himself when he is the constant victim of brutal attacks." [citation needed]

- I did many things as a [Black] Muslim that I'm sorry for now. I was a zombie then — like all [Black] Muslims — I was hypnotized, pointed in a certain direction and told to march. Well, I guess a man's entitled to make a fool of himself if he's ready to pay the cost. [citation needed]

- "I believe in the brotherhood of man, all men, but I don't believe in brotherhood with anybody who doesn't want brotherhood with me. I believe in treating people right, but I'm not going to waste my time trying to treat somebody right who doesn't know how to return the treatment." -NYC, December 12, 1964 [citation needed]

- "If I have a cup of coffee that is too strong for me because it is too black, I weaken it by pouring cream into it. I integrate it with cream. If I keep pouring enough cream in the coffee, pretty soon the entire flavor of the coffee is changed; the very nature of the coffee is changed. If enough cream is poured in, eventually you don't even know that I had coffee in this cup. This is what happened with the March on Washington. The whites didn't integrate it; they infiltrated it. Whites joined it; they engulfed it; they became so much a part of it, it lost its original flavor. It ceased to be a black march; it ceased to be militant; it ceased to be angry; it ceased to be impatient. In fact, it ceased to be a march."

Biographies and speeches

The Autobiography of Malcolm X was written by Alex Haley between 1964 and 1965, based on interviews conducted shortly before Malcolm's assassination (with an epilogue written after it), and was published in 1965. The book was named by Time magazine as one of the 10 most important nonfiction books of the 20th century.

Malcolm X Speaks: Selected Speeches and Statements ISBN 0802132138 edited by George Breitman. These speeches made during the last eight months of Malcolm's life indicate the power of his newly refined ideas.

"Malcolm X: The Man and His Times" edited with an introduction and commentary by John Henrik Clarke. An anthology of writings, speeches and manifestos along with writings about Malcolm X by an international group of African and African American scholars and activists.

"Malcolm X: The FBI File" Commentary by Clayborne Carson with an introduction by Spike Lee and edited by David Gallen. A source of information documenting the FBI's file on Malcolm beginning with his prison release in March 1953 and culminating with a 1980 request that the FBI investigate Malcolm's assassination.

The film Malcolm X was released in 1992, directed by Spike Lee. Based on the autobiography, it starred Denzel Washington as Malcolm with Angela Bassett as Betty and Al Freeman Jr. as Elijah Muhammad.

The 2001 film Ali, about boxer Muhammad Ali, played by Will Smith, also features Malcolm X, as played by Mario Van Peebles.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ p. 2-3, The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

- ↑ p. 11, The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

- ↑ p. 11, The Autobiography of Malcolm X.

- ↑ p. 36, The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The full quote is:

- Malcolm, one of life's first needs is for us to be realistic. Don't misunderstand me, now. We all like you here, you know that. But you've got to be realistic about being a nigger. A lawyer— that's no realistic goal for a nigger. You need to think about something you can be.

- ↑ Malcolm X Little, Part 01 of 24, FBI file, "II. Communist Party Activities," p. 3

- ↑ http://intranet1.sutcol.ac.uk:888/NEC/MATERIAL/PDFS/GOV_POL/A2GOV_PO/08U4_T4.PDF (PDF)

Media files

- 1930 US Census with Malcolm Little and siblings in Lansing, Michigan

- Malcolm X: We Declare Our Right (audio)

- Malcolm X: On Non-Violence (audio)

- Malcolm X: Teaching of the Quran (audio)

- Malcolm X: Responsibilities of Man (audio)

- Malcolm X: Teach Yourself, Respect Yourself & Stand Up for Yourself (audio)

- Malcolm X Oxford Debate 1964 (audio)

- Malcolm X: Who Taught You to Hate (audio)

- Malcolm X: We Need to Forget Our Differences (audio)

- Malcolm X: History Rewards All Research (audio)

- Malcolm X: Living in a Poor Neighborhood (audio)

- Malcolm X: On Politics (audio)

- Malcolm X: Uncle Tom (audio)

- Malcolm X: Interview with Professor John Leggett and Herman Blake (audio)

- Malcolm X: Once You Change Your Philosophy (audio)

External links

- Video collection of Malcolm X

- The Official Web Site of Malcolm X

- Full audio of Malcolm X speeches

- Text and Audio of Ballot or Bullet Speech from AmericanRhetoric.com

- Text of a letter written following his Hajj is given at Wikisource.

- Interview with UC Berkeley sociologist Herman Blake, 1963 (video)

- Ancestry of Malcolm X

- Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) United States Postage Stamp

- Malcolm X Gravesite

- Biography, Pictures, and Speeches

- Malcolm X Reloaded: Who Really Assassinated Malcolm X

Research sites

- Malcolm X : A Research Site Abdul Alkalimat, ed. Launched May 19, 1999. University of Toledo and Twenty-first Century Books.

- malcolm-x.org. seeks to present Malcolm X within an Islamic context. Retrieved May 19, 2005.

- Malcolm X: Make It Plain. Documentary

- Malcolm X Reference Archive. Sound files of speeches The Ballot or the Bullet, Democrats are Dixiecrats, et al. Marxist Internet Archive. Retrieved May 19, 2005.

- Malcolm X Project. Project of the Center for Contemporary Black History at Columbia University. Retrieved May 19, 2005.

- Malcolm X's FBI file

- Malcolm X - An Islamic Perspective

- Malcolm X : A Profile by Det Danske Koranselskab

Articles and reports

- Frazier, Martin. Harlem celebrates Malcolm X birthday. People's Weekly World. May 26, 2005.

- Democracy Now!. Malcolm X: Make it Plain transcript. Excerpts of the documentary, "Malcolm X: Make it Plain". Segment available via streaming Real Audio, 128k streaming Real Video, or via MP3 download from Archive.org. 37:23 minutes. Hosted by Amy Goodman. Broadcast May 19, 2005.

- Waldron, Clarence. Minister Louis Farrakhan Sets The Record Straight About His Relationship With Malcolm X. Jet Magazine. Interview, June 5, 2000. Retrieved May 19, 2005.

- M, Yahyá. The name Shabazz: Where did it come from?. Revised from 'Islamic Studies vol. 32 no.1, Spring 1993. p. 73-76. Retrieved May 19, 2005.

- Farrakhan, Louis. The Murder of Malcolm X: The Effect on Black America. Real media video webcast. Malcolm X College, Chicago, IL. February 1990.

Further reading

Articles

- Parks, Gordon. The White Devil's Day is Almost Over. Life, May 31, 1963.

- Speakman, Lynn. Who Killed Malcolm X? The Valley Advocate, November 26, 1992, pp. 3-6.

- Vincent, Theodore. The Garveyite Parents of Malcolm X. The Black Scholar, vol. 20, #2, April, 1989.

- Handler ,M.S.Malcolm X cites role in U.N. Fight. New York Times, Jan 2, 1965; pg. 6, 1.

- Montgomery, Paul L. Malcolm X a Harlem Idol on Eve of Murder Trial. New York Times, Dec 6, 1965; pg. 46, 1

- Bigart, Homer. Malcolm X-ism Feared by Rustin. New York Times, Mar 4, 1965; pg. 15, 1

- Arnold, Martin. Harlem is Quiet as Crowds Watch Malcolm X Rites. New York Times, Feb 28, 1965; pg. 1, 2

- Loomis, James. Death of Malcolm X. New York Times. Feb 27, 1965; pg. 24, 1

- n/a. Malcolm X and Muslims. New York Times, Feb 21, 1965; pg. E10, 1

- n/a. Malcolm X. New York Times, Feb 22, 1965; pg. 20, 1

- n/a. Malcolm X Reports He Now Represents Muslim World Unit. New York Times, Oct 11, 1964; pg. 13, 1

- Lelyveld, Joseph. Elijah Muhammad Rallies His Followers in Harlem. New York Times, Jun 29, 1964; pg. 1, 2

- n/a. Malcolm X Woos 2 Rights Leaders. New York Times, May 19, 1964; pg. 28, 1

- n/a. 1,000 In Harlem Cheer Malcolm X. New York Times, Mar 23, 1964; pg. 18, 1

- Handler, M.S. Malcolm X Sees Rise in Violence. New York Times, Mar 13, 1964; pg. 20, 1

- n/a. Malcolm X Disputes Nonviolence Policy. New York Times, Jun 5, 1963; pg. 29, 1

- Apple, R.W. Malcolm X Silenced for Remarks On Assassination of Kennedy. New York Times, Dec 5, 1963; pg. 22, 1

- Ronan, Thomas P. Malcolm X Tells Rally In Harlem Kennedy Fails to Help Negroes. New York Times, Jun 30, 1963; pg. 45, 1

- n/a. 4 Are Indicted Here in Malcolm X Case. New York Times, Mar 11, 1965; pg. 66, 1

- Handler, M.S. Malcolm X Seeks U.N. Negro Debate. Special to The New York Times; New York Times, Aug 13, 1964; pg. 22, 1

Books

- Autobiography of Malcolm X (co-author Alex Haley) ISBN 0812419537

- Acuna, Rodolfo. Occupied America: A History of Chicanos. New York: Harper & Row, 1981.

- Alkalimat, Abdul. Malcolm X for Beginners. New York: Writers and Readers, 1990.

- Asante, Molefi K. Malcolm X as Cultural Hero: and Other Afrocentric Essays. Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1993.

- Baldwin, James. One Day, When I Was Lost: A Scenario Based On Alex Haley's "The Autobiography Of Malcolm X". New York: Dell, 1992.

- Breitman, George, ed. Malcolm X Speaks. New York: Merit, 1965.

- Breitman, George. The Last Year of Malcolm X: The Evolution of a Revolutionary. New York: Pathfinder, 1967.

- Breitman, George and Herman Porter. The Assassination of Malcolm X. New York: Pathfinder, 1976.

- Brisbane, Robert. Black Activism. Valley Forge, Pennsylvania: Judson Press, 1974.

- Carson, Claybourne. Malcolm X: The FBI File. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1991.

- Carson, Claybourne, et al. The Eyes on the Prize Civil Rights Reader. New York: Penguin, 1991.

- Clarke, John Henrik, ed. Malcolm X; the Man and His Times. New York: Macmillan, 1969.

- Cleage, Albert B. and George Breitman. Myths About Malcolm X: Two Views. New York: Merit, 1968.

- Collins, Rodney P. The Seventh Child. New York: Dafina; London: Turnaround, 2002.

- Cone, James H. Martin & Malcolm & America: A Dream or A Nightmare. Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1991.

- Davis, Thulani. Malcolm X: The Great Photographs. New York: Stewart, Tabon and Chang, 1992.

- DeCaro, Louis A. On The Side of My People: A Religious Life of Malcolm X. New York: New York University, 1996.

- DeCaro, Louis A. Malcolm and the Cross: The Nation of Islam, Malcolm X, and Christianity. New York: New York University, 1998.

- Doctor, Bernard Aquina. Malcolm X for Beginners. New York: Writers and Readers, 1992.

- Dyson, Michael Eric. Making Malcolm: The Myth and Meaning of Malcolm X. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Essien-Udom, E. U. Black Nationalism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962.

- Evanzz, Karl. The Judas Factor: The Plot to Kill Malcolm X. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1992.

- Franklin, Robert Michael. Liberating Visions: Human Fulfillment And Social Justice In African-American Thought. Minneapolis, MN : Fortress Press, 1990.

- Friedly, Michael. The Assassination of Malcolm X. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1992.

- Gallen, David, ed. Malcolm A to Z: The Man and His Ideas. New York: Carroll and Graf, 1992.

- Garrow, David. Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: Vintage, 1988.

- Goldman, Peter. The Death and Life of Malcolm X. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

- Hampton, Henry and Steve Fayer. Voices of Freedom: Oral Histories from the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s. New York: Bantam, 1990.

- Harding, Vincent, Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis. We Changed the World: African Americans, 1945-1970. The Young Oxford History of African Americans, v. 9. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Hill, Robert A. Marcus Garvey: Life and Lessons. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987.

- Jamal, Hakim A. From The Dead Level: Malcolm X and Me. New York: Random House, 1972.

- Jenkins, Robert L. The Malcolm X Encyclopedia. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2002.

- Karim, Benjamin with Peter Skutches and David Gallen. Remembering Malcolm. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1992.

- Kly, Yussuf Naim, ed. The Black Book: The True Political Philosophy of Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El Shabazz). Atlanta: Clarity Press, 1986.

- Leader, Edward Roland. Understanding Malcolm X: The Controversial Changes in His Political Philosophy. New York: Vantage Press, 1993.

- Lee, Spike with Ralph Wiley. By Any Means Necessary: The Trials and Tribulations of The Making Of Malcolm X. New York, N.Y.: Hyperion, 1992.

- Lincoln, C. Eric. The Black Muslims in America. Boston, Beacon. 1961.

- Lomax, Louis. When the Word is Given. Cleveland: World, 1963.

- Maglangbayan, Shawna. Garvey, Lumumba, and Malcolm: National-Separatists. Chicago, Third World Press 1972.

- Marable, Manning. On Malcolm X: His Message & Meaning. Westfield, N.J.: Open Media, 1992.

- Martin, Tony. Race First. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 1976.

- Myers, Walter Dean. Malcolm X By Any Means Necessary. New York: Scholastic, 1993.

- Perry, Bruce. Malcolm: The Life of A Man Who Changed Black America. New York: Station Hill, 1991.

- Randall, Dudley and Margaret G. Burroughs, ed. For Malcolm; Poems on The Life and The Death of Malcolm X. Preface and Eulogy By Ossie Davis. Detroit: Broadside Press, 1967.

- Sales, William W. From Civil Rights To Black Liberation: Malcolm X And The Organization Of Afro-American Unity. Boston, MA: South End Press, 1994.

- Shabazz, Ilyasah. Growing Up X. New York: One World, 2002.

- Strickland, William, et al. Malcolm X: Make It Plain. Penquin Books, 1994.

- T'Shaka, Oba. The Political Legacy of Malcolm X. Richmond, Calif.: Pan Afrikan Publications, 1983.

- Tuttle, William. Race Riot: Chicago, The Red Summer of 1919. New York: Atheneum, 1970.

- Vincent, Theodore. Black Power and the Garvey Movement. San Francisco: Ramparts, 1972.

- Wood, Joe, ed. Malcolm X: In Our Own Image. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992.

- Woodward, C. Vann. Origins of the New South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1967.

ar:مالكوم إكس zh-min-nan:Malcolm X bs:Malcolm X da:Malcolm X de:Malcolm X et:Malcolm X es:Malcolm X eo:Malcolm X fr:Malcolm X hr:Malcolm X id:Malcolm X is:Malcolm X it:Malcolm X he:מלקולם אקס ms:Malcolm X nl:Malcolm X ja:マルコムX no:Malcolm X pl:Malcolm X pt:Malcolm X simple:Malcolm X fi:Malcolm X sv:Malcolm X tr:Malcolm X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.