Industrialization

Currently working on —Jennifer Tanabe June 2021.

Industrialisation (or industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This means converting to a socioeconomic order in which industry is dominant, which involves an extensive re-organization of the economy for the purpose of manufacturing.

The reorganization of the economy has many unintended consequences both economically and socially. As industrial workers' incomes rise, markets for consumer goods and services of all kinds tend to expand and provide a further stimulus to industrial investment and economic growth. Moreover, family structures tend to shift as extended families tend not to live together in one household or location, as family members migrated following job opportunities.

History

In most pre-industrial societies, the majority of the population were focused on producing their means of survival through subsistence farming. Famines were frequent. Some, such as classical Athens, had trade and commerce as significant factors. As a result, Greeks could enjoy wealth far beyond a sustenance standard of living through the use of slavery.[2]

A process called proto-industrialisation occurred in Europe as well as in Mughal India,[3] and was the first stage prior to the Industrial Revolution.[4]

In his 1728 work on the economy of England, A Plan of the English Commerce, Daniel Defoe describes how England developed from being a raw wool producer to the manufacture of finished woolen textiles. Defoe writes that Tudor monarchs, especially Henry VII of England and Elizabeth I, implemented policies that today would be described as protectionist, such as imposing high tariffs on the importation of finished woolen goods, imposing high taxes on raw wool exports leaving England, bringing in artisans skilled in wool textile manufacturing from the Low Countries, awarding selective government-granted monopoly rights in geographic areas of England deemed suitable for textile industrial production, and granting government-sponsored industrial espionage to develop the early English textile industry.[5]

After the victory of the East India Company in the Battle of Plassey over the rulers of the Bengal Subah, industrialisation through innovation in manufacturing processes first started with the Industrial Revolution in the north-west and Midlands of England in the 18th century.[6] It spread to Europe and North America in the 19th century.

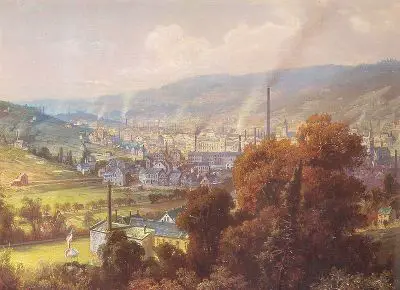

After the last stage of the Proto-industrialization, the first transformation from an agricultural to an industrial economy is known as the Industrial Revolution and took place from the mid-18th to early 19th century in certain areas in Europe and North America; starting in Great Britain, followed by Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, and France.[7] Characteristics of this early industrialisation were technological progress, a shift from rural work to industrial labor, financial investments in new industrial structure, and early developments in class consciousness and theories related to this.[8] Later commentators have called this the First Industrial Revolution.[9]

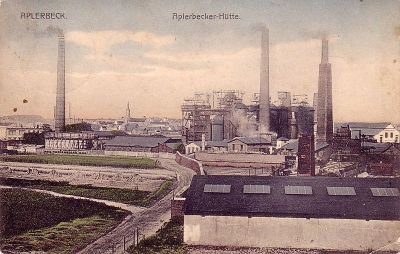

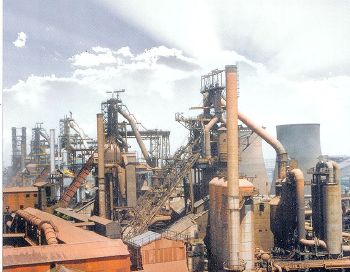

The "Second Industrial Revolution" labels the later changes that came about in the mid-19th century after the refinement of the steam engine, the invention of the internal combustion engine, the harnessing of electricity and the construction of canals, railways and electric-power lines. The invention of the assembly line gave this phase a boost. Coal mines, steelworks, and textile factories replaced homes as the place of work. [10][11][12]

By the end of the 20th century, East Asia had become one of the most recently industrialised regions of the world.[13] The BRICS states (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) are undergoing the process of industrialisation.[8]

Industrial revolution in Europe

The era known as the Industrial Revolution was a period in which fundamental changes occurred in agriculture, textile and metal manufacture, transportation, economic policies and the social structure in England ( and afterwards elsewhere in Europe). This period is appropriately labeled “revolution,” for it thoroughly destroyed the old manner of doing things; yet the term is simultaneously inappropriate, for it connotes abrupt change.

The changes that occurred during this period (1760-1850), in fact, occurred gradually. The year 1760 is generally accepted as the “eve” of the Industrial Revolution. In reality, this eve began more than two centuries before this date. The late 18th century and the early l9th century brought to fruition the ideas and discoveries of those who had long passed on, such as, Galileo, Bacon, Descartes, and others.

The United Kingdom was the first country in the world to industrialize.[14] In the 18th and 19th centuries, the UK experienced a massive increase in agricultural productivity known as the British Agricultural Revolution, which enabled an unprecedented population growth, freeing a significant percentage of the workforce from farming, and helping to drive the Industrial Revolution.

Due to the limited amount of arable land and the overwhelming efficiency of mechanized farming, the increased population could not be dedicated to agriculture. New agricultural techniques allowed a single peasant to feed more workers than previously; however, these techniques also increased the demand for machines and other hardware, which had traditionally been provided by the urban artisans. Artisans, collectively called bourgeoisie, employed rural exodus workers to increase their output and meet the country's needs.

British industrialization involved significant changes in the way that work was performed. The process of creating a good was divided into simple tasks, each one of them being gradually mechanized in order to boost productivity and thus increase income. The new machines helped to improve the productivity of each worker. However, industrialization also involved the exploitation of new forms of energy. In the pre-industrial economy, most machinery was powered by human muscle, by animals, by wood-burning or by water-power. With industrialization these sources of fuel were replaced with coal, which could deliver significantly more energy than the alternatives. Much of the new technology that accompanied the industrial revolution was for machines which could be powered by coal. One outcome of this was an increase in the overall amount of energy consumed within the economy - a trend which has continued in all industrialized nations to the present day.[15]

The accumulation of capital allowed investments in the scientific conception and application of new technologies, enabling the industrialization process to continue to evolve. The industrialization process formed a class of industrial workers who had more money to spend than their agricultural cousins. They spent this on items such as tobacco and sugar, creating new mass markets that stimulated more investment as merchants sought to exploit them.[16]

The mechanization of production spread to the countries surrounding England geographically in Europe such as France and to British settler colonies, helping to make those areas the wealthiest, and shaping what is now known as the Western world.

Some economic historians argue that the possession of so-called 'exploitation colonies' eased the accumulation of capital to the countries that possessed them, speeding up their development.[17] The consequence was that the subject country integrated a bigger economic system in a subaltern position, emulating the countryside, which demands manufactured goods and offers raw materials, while the colonial power stressed its urban posture, providing goods and importing food. A classical example of this mechanism is said to be the triangular trade, which involved England, southern United States and western Africa. Some have stressed the importance of natural or financial resources that Britain received from its many overseas colonies or that profits from the British slave trade between Africa and the Caribbean helped fuel industrial investment.[18]

With these arguments still find some favor with historians of the colonies, most historians of the British Industrial Revolution do not consider that colonial possessions formed a significant role in the country's industrialization. Whilst not denying that Britain could profit from these arrangement, they believe that industrialization would have proceeded with or without the colonies.[19]

Early industrialisation in other countries

The Industrial Revolution spread southwards and eastwards from its origins in Northwest Europe.

After the Convention of Kanagawa issued by Commodore Matthew C. Perry forced Japan to open the ports of Shimoda and Hakodate to American trade, the Japanese government realised that drastic reforms were necessary to stave off Western influence. The Tokugawa shogunate abolished the feudal system. The government instituted military reforms to modernise the Japanese army and also constructed the base for industrialisation. In the 1870s, the Meiji government vigorously promoted technological and industrial development that eventually changed Japan to a powerful modern country.

In a similar way, Russia which suffered during the Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War. The Soviet Union's centrally controlled economy decided to invest a big part of its resources to enhance its industrial production and infrastructures to assure its survival, thus becoming a world superpower.[20] During the Cold war, the other Warsaw Pact countries, organised under the Comecon framework, followed the same developing scheme, albeit with a less emphasis on heavy industry.

Southern European countries such as Spain or Italy industrialized moderately during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and then experienced economic booms after the Second World War, caused by a healthy integration of the European economy.[21][22]

The Third World

A similar state-led developing programme was pursued in virtually all the Third World countries during the Cold War, including the socialist ones, but especially in Sub-Saharan Africa after the decolonization period.[citation needed] The primary scope of those projects was to achieve self-sufficiency through the local production of previously imported goods, the mechanization of agriculture and the spread of education and health care. However, all those experiences failed bitterly[citation needed] due to a lack of realism[citation needed]: most countries did not have a pre-industrial bourgeoisie able to carry on a capitalistic development or even a stable and peaceful state. Those aborted experiences left huge debts toward western countries and fuelled public corruption.[citation needed]

Petrol-producing countries

Oil-rich countries saw similar failures in their economic choices. An EIA report stated that OPEC member nations were projected to earn a net amount of $1.251 trillion in 2008 from their oil exports.[23] Because oil is both important and expensive, regions that had big reserves of oil had huge liquidity incomes. However, this was rarely followed by economic development. Experience shows that local elites were unable to re-invest the petrodollars obtained through oil export, and currency is wasted in luxury goods.[24]

This is particularly evident in the Persian Gulf states, where the per capita income is comparable to those of western nations, but where no industrialization has started. Apart from two little countries (Bahrain and the United Arab Emirates), the Persian Gulf states have not diversified their economies, and no replacement for the upcoming end of oil reserves is envisaged.[25]

Industrialization in Asia

Apart from Japan, where industrialization began in the late nineteenth century, a different pattern of industrialization followed in East Asia. One of the fastest rates of industrialization occurred in the late 20th century across four places known as the Asian tigers (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan). Between the early 1960s and 1990s, they underwent rapid industrialization and maintained exceptionally high growth rates of more than 7 percent a year. By the early 21st century, these economies had developed into high-income economies, specializing in areas of competitive advantage. Hong Kong and Singapore have become leading international financial centers, whereas South Korea and Taiwan are leaders in manufacturing electronic components and devices.

Prior to the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the growth of the Four Asian Tiger economies (commonly referred to as "the Asian Miracle") has been attributed to export oriented policies and strong development policies. The existence of stable governments and well structured societies, strategic locations, heavy foreign investments, a low cost skilled and motivated workforce, a competitive exchange rate, and low custom duties supported their quick growth. Unique to these economies were the sustained rapid growth and high levels of equal income distribution. A World Bank report suggests two development policies among others as sources for the Asian miracle: factor accumulation and macroeconomic management.[26]

In the case of South Korea, the largest of the four Asian tigers, a very fast-paced industrialization took place as it quickly moved away from the manufacturing of value-added goods in the 1950s and 60s into the more advanced steel, shipbuilding and automotive industry in the 1970s and 80s, focusing on the high-tech and service industry in the 1990s and 2000s. As a result, South Korea became a major economic power.

This starting model was afterwards successfully copied in other larger Eastern and Southern Asian countries. The success of this phenomenon led to a huge wave of offshoring – i.e., Western factories or Tertiary Sector corporations choosing to move their activities to countries where the workforce was less expensive and less collectively organized.

China and India, while roughly following this development pattern, made adaptations in line with their own histories and cultures, their major size and importance in the world, and the geo-political ambitions of their governments, etc..

Meanwhile, India's government is investing in economic sectors such as bioengineering, nuclear technology, pharmaceutics, informatics, and technologically oriented higher education, exceeding its needs, with the goal of creating several specialization poles able to conquer foreign markets.

Both China and India have also started to make significant investments in other developing countries, making them significant players in today's world economy.

Newly industrialized countries

Since the mid-late twentieth century, most countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, including Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, Mexico, Philippines, South Africa, and Turkey have experienced substantial industrial growth, fuelled by exporting to countries that have bigger economies: the United States, China, India and the EU. They are sometimes called newly industrialized countries (NICs).

These countries have economies have not yet reached a developed country's status but have, in a macroeconomic sense, outpaced their developing counterparts. Such countries are still considered developing nations and only differ from other developing nations in the rate at which an NIC's growth is much higher over a shorter allotted time period compared to other developing nations.[27] Another characterization of NICs is that of countries undergoing rapid economic growth (usually export-oriented).[28] Incipient or ongoing industrialization is an important indicator of an NIC. In many NICs, social upheaval can occur as primarily rural, or agricultural, populations migrate to the cities, where the growth of manufacturing concerns and factories can draw many thousands of laborers. NICs introduce many new immigrants looking to improve their social and/or political status through newly formed democracies and the increase in wages that most individuals who partake in such changes would obtain.

Consequences

Transportation

As an integral part of determining the cost and availability of manufactured products was improvement of transportation that stimulated the course of the Industrial Revolution. Finished products, raw materials, food and people needed a reliable, quicker and less costly system of transportation. Canals and rivers had long been used as a means of internal transportation.

The principles of rail transport were already in use in the late 1700s. By 1800 more than 200 miles of tramway served coal mines. It is not surprising, then, to find a number of engineers connected with coal mines searching for a way to apply the steam engine to railways.

A pioneer in railroads that bears mentioning is George Stephenson. The Stockton to Darlington line was the first public railroad to use locomotive traction and carry passengers, as well as freight.

Railroads dominated the transportation scene in England for nearly a century. Railroads proliferated in England, from 1,000 miles in 1836 to more than 7,000 miles built by 1852. Here again is another example of economic necessity producing innovation. The development of reliable, efficient rail service was crucial to the growth of specific industries and the overall economy.

Capital

Prior to industrialization in England, land was the primary source of wealth. However, a new source of great wealth grew from the Industrial Revolution, derived from the ownership of factories and machinery. Those investors in factories and machinery cannot be identified to any single class of people (landed aristocracy, industrialists, merchants). It was these capitalists who gave the necessary impetus to the speedy growth of the Industrial Revolution.

Two kinds of capital were needed: long-term capital to expand present operations, and short-term capital to purchase raw materials, maintain inventories and to pay wages to their employees. The long-term capital needs were met by mortgaging factory buildings and machinery. It was the need for short-term capital which presented some problems.

That need was accommodated by extending credit to the manufacturers by the producers or dealers. Often, a supplier of raw materials waited from 6 to 12 months for payment of his goods, after the manufacturer was paid for the finished product.

The Bank of England, established in the late 1690s, did not accommodate the needs of the manufacturers. It concentrated its interest on the financial affairs of state and those of the trading companies and merchants of London.

The early 1700s brought with it the first country ( private ) banks, founded by those who were involved in a variety of endeavors (goldsmith, merchant, manufacturer). Many industrialists favored establishing their own banks as an outlet for the capital accumulated by their business and as a means for obtaining cash for wages. Their limited resources were inadequate to meet the demands of the factory economy. A banking system was eventually set up to distribute capital to areas where it was needed, drawing it from areas where there was a surplus.

Pollution

Historically, industrialization was associated with an increase in Pollution both from the toxic waste from factories, especially those producing chemicals, and from industries heavily dependent on fossil fuels. With an increasing focus on sustainable development and green industrial policy practices, industrialization increasingly includes technological leapfrogging, with direct investment in more advanced, cleaner technologies.

Changes in social structure

The Industrial revolution was accompanied with a great deal of changes in social structure, the main change being a transition from farm work to factory related activities.[30] This resulted to the creation of a class structure that differentiated the commoners from the well off and the working category. It distorted the family system as most people moved into cities and left the farm areas, consequently playing a major role in the transmission of diseases. The place of women in society then shifted from being home cares to employed workers hence reducing the number of children per household. Furthermore industrialization contributed to increased cases of child labor and thereafter education systems.[31]

In the l8th century the population grew at a faster rate than ever before. There are four primary reasons which may be cited for this growth: a decline in the death rate, an increase in the birth rate, the virtual elimination of the dreaded plagues and an increase in the availability of food. The latter is probably the most significant of these reasons, for English people were consuming a much healthier diet.

There were several other reasons for the growth of the population, in addition to those above. Industry provided higher wages to individuals than was being offered in the villages. This allowed young people to marry earlier in life, and to produce children earlier. Also, industry provided people with improved clothing and housing, though it took a long time for housing conditions to improve.

With the adoption of the factory system, we find a shift in population. Settlements grew around the factories. In some cases factories started in existing towns, which was desirable because a labor pool was readily available.

The development of the steam engine to drive machinery freed the mill owners from being locked into a site that was close to swiftly moving water. Thus, factories could be located closer to existing population centers or seaports, fulfilling the need for labor and transportation of materials.

Urbanization

As the Industrial Revolution was a shift from the agrarian society, people migrated from villages in search of jobs to places where factories were established. This shifting of rural people led to urbanization and increase in the population of towns. The concentration of labor in factories has increased urbanization and the size of settlements, to serve and house the factory workers.

Changes in family structure

Family structure changes with industrialisation. Sociologist Talcott Parsons noted that in pre-industrial societies there is an extended family structure spanning many generations who probably remained in the same location for generations. In industrialised societies the nuclear family, consisting of only parents and their growing children, predominates. Families and children reaching adulthood are more mobile and tend to relocate to where jobs exist. Extended family bonds become more tenuous.[32]

Notes

- ↑ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ↑ Ben Akrigg, Population and Economy in Classical Athens (Cambridge University Press, 2019, ISBN 1107027098).

- ↑ Giorgio Riello, Tirthankar Roy (2009). How India Clothed the World: The World of South Asian Textiles, 1500-1850. Brill Publishers. ISBN 9789047429975.

- ↑ József Böröcz (2009-09-10). The European Union and Global Social Change. Routledge. ISBN 9781135255800. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Chang, Ha-Joon "Bad Samaritans: The Myth of Free Trade and the Secret History of Capitalism" (New York: Random House, 2008), p. 229 quoting "A Plan for the English Commerce, p. 95

- ↑ The Origins of the Industrial Revolution in England by Steven Kreis. Last Revised 11 October 2006. Accessed April 2008

- ↑ Griffin, Emma, A short History of the British Industrial Revolution. In 1850 over 50 percent of the British lived and worked in cities. London: Palgrave (2010)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 (2016) "Sustainable Industrialization in Africa: Toward a New Development Agenda", Sustainable Industrialization in Africa. Springer, 1–19. DOI:10.1007/978-1-137-56112-1_1. ISBN 978-1-349-57360-8. [verification needed]

- ↑ Pollard, Sidney: Peaceful Conquest. The Industrialisation of Europe 1760–1970, Oxford 1981.

- ↑ Buchheim, Christoph: Industrielle Revolutionen. Langfristige Wirtschaftsentwicklung in Großbritannien, Europa und in Übersee, München 1994, S. 11-104.

- ↑ Jones, Eric: The European Miracle: Environments, Economics and Geopolitics in the History of Europe and Asia, 3. ed. Cambridge 2003.

- ↑ Henning, Friedrich-Wilhelm: Die Industrialisierung in Deutschland 1800 bis 1914, 9. Aufl., Paderborn/München/Wien/Zürich 1995, S. 15-279.

- ↑ Industry & Enterprise: A International Survey Of Modernisation & Development, ISM/Google Books, revised 2nd edition, 2003. Template:ISBN. [1] {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}}

- ↑ Industrial Revolution. Archived from the original on 27 April 2008. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Griffin, Emma. Patterns of Industrialisation. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ Enslavement and industrialization Robin Blackburn , BBC British History. Published: 18 December 2006 Accessed April 2008

- ↑ Williams, Eric (1965). Capitalism and Slavery.

- ↑ Pomeranz, Kenneth (2000). The Great Divergence. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Griffin, Emma (2010). A Short History of the British Industrial Revolution. Palgrave.

- ↑ Joseph Stalin and the industrialisation of the USSR {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} Learning Curve website, The UK National Archives. Accessed April 2008

- ↑ BOOM E MIRACOLO ITALIANO ANNI '50-60 (CRONOLOGIA)

- ↑ Queer transitions in contemporary Spanish culture: from Franco to la movida, By Gema Pérez-Sánchez

- ↑ OPEC to earn $1.251 trillion from oil exports - EIA, Reutrs

- ↑ Understanding New Middle East, Behzad Shahandeh, The Korea Times, 31 October 2007

- ↑ Background Note: Saudi Arabia

- ↑ (1994) "The East Asian Miracle: Four Lessons for Development Policy", NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1994, Volume 9. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 219–269. DOI:10.1086/654251. ISBN 978-0-262-06172-8.

- ↑ Patrick H. O’Neil (2018). "Chapter 10: Developing Countries", Essentials of Comparative Politics, 6th, W. W. Norton & Company, 304–337. ISBN 978-0-393-62458-8.

- ↑ Dominik Boddin (October 2016). The Role of Newly Industrialized Economies in Global Value Chains. IMF Working Paper.

- ↑ Bairoch, Paul (1995). Economics and World History: Myths and Paradoxes. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03463-8.

- ↑ revolution, social. social effects of industrial revolution.

- ↑ revolution, social. social effect of industrial revolution.

- ↑ The effect of industrialisation on the family, Talcott Parsons, the isolated nuclear family {{#invoke:webarchive|webarchive}} Black's Academy. Educational Database. Accessed April 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Akrigg, Ben. Population and Economy in Classical Athens. Cambridge University Press, 2019. ISBN 1107027098

- Cameron, R. France and the Economic Development of Europe, 1800-1914, Princeton University Press Princeton, NJ, 1961

- Cameron, R.,(ed. with the collaboration of Olga Crisp, H. T. Patrick and R. Tilly), Banking in the Early Stages of Industrialization: A Study of Comparative Economic History,Oxford University Press, New York,1967

- Cameron, R. A Concise Economic History of the World, Oxford University Press, Oxford,1989

- Gerschenkron, A., Economic backwardness in historical perspective: a book of essays, Belknap Press of Harvard University Press,Cambridge, Massachusettes, 1962

- Gerschenkron, A., Continuity in history, and other essays, Cambridge, Massachusettes: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1968

- Karasek, M.,”Institutional and Political Challenges and Opportunities for Integration in Central Asia” , CAG Portal Forum 2005,Exh. 3 ( & discussion ),

- Landes, David, The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1969, p. 115

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.