Difference between revisions of "Hieroglyph" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

{{Main|Egyptian hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Egyptian hieroglyphs}} | ||

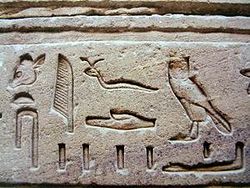

[[Image:Egypt Hieroglyphe4.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Hieroglyphs typical of the Graeco-Roman period]] | [[Image:Egypt Hieroglyphe4.jpg|right|250px|thumb|Hieroglyphs typical of the Graeco-Roman period]] | ||

| − | '''Egyptian hieroglyphs''' ({{pronEng|ˈhaɪərəʊɡlɪf}}; from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] {{lang|grc-Grek|ἱερογλύφος}} "[[hieros|sacred]] [[glyph|carving]]" | + | '''Egyptian hieroglyphs''' ({{pronEng|ˈhaɪərəʊɡlɪf}}; from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] {{lang|grc-Grek|ἱερογλύφος}} "[[hieros|sacred]] [[glyph|carving]]," also '''hieroglyphic''' = {{lang|grc-Grek|τὰ ἱερογλυφικά [γράμματα]}}) was a formal [[writing system]] used by the [[ancient Egypt]]ians that contained a combination of [[logograph]]ic and [[alphabet]]ic elements. Egyptians used [[cursive hieroglyphs]] for religious literature on [[papyrus]] and wood. Less formal variations of the script, called [[hieratic]] and [[demotic (Egyptian)|demotic]], are technically not hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including single-consonant characters that functioned like an alphabet; logographs, representing [[morpheme]]s; and determinatives, which narrowed down the [[semantics|meaning]] of a logographic or phonetic words. |

| − | Hieroglyphs emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on [[Gerzean]] pottery from ''circa'' 4000 | + | Hieroglyphs emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on [[Gerzean]] pottery from ''circa'' 4000 B.C.E. resemble hieroglyphic writing. For many years the earliest known hieroglyphic inscription was the [[Narmer Palette]], found during excavations at [[Hierakonpolis]] (modern Kawm al-Ahmar) in the 1890s, which has been dated to ''circa'' 3200 B.C.E. However, in 1998 a German archaeological team under [[Günter Dreyer]] excavating at [[Abydos, Egypt|Abydos]] (modern [[Umm el-Qa'ab]]) uncovered tomb U-j of a [[Predynastic Egypt|Predynastic]] ruler, and recovered three hundred clay labels inscribed with [[proto-hieroglyphs]], dating to the [[Naqada IIIA]] period of the 33rd century B.C.E.<ref>[http://www.exn.ca/egypt/story.asp?st=Lifestyles The origins of writing], [[Discovery Channel]] (1998-12-15)</ref><ref>Richard Mattessich (Jun 2002) [http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3657/is_200206/ai_n9107461 The oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt], ''The Accounting Historians Journal''.</ref> The first full sentence written in hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression found in the tomb of [[Seth-Peribsen]] at Umm el-Qa'ab, which dates from the [[Second dynasty of Egypt|Second Dynasty]]. In the era of the [[Old Kingdom]], the [[Middle Kingdom]] and the [[New Kingdom]], about 800 hieroglyphs existed. By the [[Greco-Roman]] period, they numbered more than 5,000.<ref>Antonio Loprieno, <cite>Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction</cite>, Cambridge University Press, 1995 p.12</ref> |

===Cursive hieroglyphs=== | ===Cursive hieroglyphs=== | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

===Cretan hieroglyphs=== | ===Cretan hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Cretan hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Cretan hieroglyphs}} | ||

| + | '''Cretan hieroglyphs''' are found on artifacts of [[Bronze Age]] [[Minoan civilization|Minoan]] [[Crete]] (early to mid 2nd millennium B.C.E., [[Minoan chronology|MM I to MM III]], overlapping with [[Linear A]] from MM IIA at the earliest). Symbol inventories have been compiled by Evans (1909), Meijer (1982), Olivier/Godart (1996). The known corpus has been edited in 1996 as ''CHIC'' (Olivier/Godard 1996), listing a total of 314 items, mainly excavated at four locations: | ||

| + | *"Quartier Mu" at [[Malia (city)|Malia]] (MM II) | ||

| + | *the hieroglyphic deposit at Malia palace (MM III) | ||

| + | *the hieroglyphic deposit at [[Knossos]] (MM II or III) | ||

| + | *the [[Petras]] deposit (MM IIB). | ||

| + | |||

| + | The corpus consists of: | ||

| + | *clay documents with incised inscriptions (CHIC H: 1-122) | ||

| + | *sealstone impressions (CHIC I: 123-179) | ||

| + | *sealstones (CHIC S: 180-314) | ||

| + | *the [[Malia altar stone]] | ||

| + | *the [[Phaistos Disk]] | ||

| + | *the [[Arkalochori Axe]] | ||

| + | *seal fragment HM 992, showing a single symbol, identical to Phaistos Disk glyph 21. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The relation of the last three items with the script of the main corpus is uncertain. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The glyph inventory as presented by CHIC consists of 96 syllabograms, ten of which double as logograms, an additional 23 logograms, 13 fractions (including 4 in ligature), four levels of numerals (units, tens, hundreds, thousands) and two types of punctuation. Many symbols have apparent [[Linear A]] counterparts, so that it is tempting to insert [[Linear B]] sound values. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Besides the supposed evolution of the hieroglyphs into the linear scripts, possible relations to [[Anatolian hieroglyph]]s were suggested, as well as to the [[Cypriot syllabary]]. | ||

| + | |||

===Anatolian hieroglyphs=== | ===Anatolian hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Anatolian hieroglyphs}} | ||

| + | [[Image:Troy VIIb hieroglyphic seal reverse.png|thumb|160px|Drawing of the hieroglyphic seal found in the [[Troy VIIb]] layer.]] | ||

| + | '''Anatolian hieroglyphs''' are an indigenous [[logographic]] script native to central '''[[Anatolia]]''', consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as '''Hittite hieroglyphs''', but the language they encode proved to be [[Hieroglyphic Luwian|Luwian]], not [[Hittite language|Hittite]], and the term '''Luwian hieroglyphs''' is used in English publications. They are typologically similar to [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s, but do not derive graphically from that script, and they are not known to have played the sacred role of hieroglyphs in Egypt. There is no demonstrable connection to [[Hittite cuneiform]].<ref>A. Payne, ''Hieroglyphic Luwian'' (2004), p. 1.</ref> <ref>Melchert, H. Craig. 2004. "Luvian," in ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages'', ed. Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56256-2</ref> <ref>Melchert, H. Craig. 1996. "Anatolian Hieroglyphs," in ''The World's Writing Systems'', ed. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Anatolian hieroglyphs are attested from the third and second millennia BCE across Anatolia and into modern Syria. The earliest examples occur on personal [[seal (device)|seal]]s, but these consist only of names, titles, and auspicious signs, and it is not certain that they represent language. Most actual texts are found as monumental inscriptions in stone, though a few documents have survived on lead strips. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The first monumental inscriptions confirmed as Luwian date to the [[Late Bronze Age]], ca. 14th to 13th centuries B.C.E. And after some two centuries of sparse material the hieroglyphs resume in the Early [[Iron Age]], ca. 10th to 8th centuries. In the early 7th century, the Luwian hieroglyphic script, by then aged some 1,300 years, falls into oblivion. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | It is obvious that the script was designed for the [[Luwian language]] (notably because of the absence of an ''e'' series), which when used is known as [[Hieroglyphic Luwian]], and no texts recording another language are known,<ref>R. Plöchl, ''Einführung ins Hieroglyphen-Luwische'' (2003), p. 12.</ref> although there is occasionally foreign material like [[Hurrian]] theonyms, or glosses in [[Urartian language|Urartian]] (such as [[Image:Hieroglyph Luwian Urartian aqarqi.jpg|500x33px]] ''á - ḫá+ra - ku'' for | ||

| + | [[Image:Hieroglyph Urartian aqarqi.jpg|100x33px]] ''aqarqi'' or [[Image:Hieroglyph Luwian Urartian tyerusi_1.jpg|500x33px]] ''tu - ru - za'' for [[Image:Hieroglyph Urartian tyerusi.jpg|100x33px]] ''ṭerusi'', two units of measurement). | ||

| − | + | As in Egyptian, characters may be logographic or phonographic—that is, they may be used to represent words or sounds. The number of phonographic signs is limited. Most represent CV syllables, though there are a few disyllabic signs. A large number of these are ambiguous as to whether the vowel is ''a'' or ''i.'' Some signs are dedicated to one use or another, but many are flexible. | |

| − | |||

| + | Words may be written logographically, phonetically, mixed (that is, a logogram with a [[phonetic complement]]), and may be preceded by a [[determinative]]. Other than the fact that the phonetic glyphs form a [[syllabary]] rather that indicating only consonants, this system is analogous to the system of Egyptian hieroglyphs. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Unlike [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s, the lines of Luwian hieroglyphs are written alternately left-to-right and right-to-left. This practice was called by the [[Ancient Greek|Greeks]] ''[[boustrophedon]]'', meaning "as the ox turns" (as when plowing a field). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some scholars compare the [[Phaistos Disc]] and [[Cretan hieroglyphs]] as possibly related scripts, but there is no consensus regarding this. | ||

===Mayan hieroglyphs=== | ===Mayan hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Mayan hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Mayan hieroglyphs}} | ||

| + | The '''Maya script''', also known as '''Maya hieroglyphs''', was the [[Writing systems|writing system]] of the [[pre-Columbian]] [[Maya civilization]] of [[Mesoamerica]], presently the only deciphered [[Mesoamerican writing systems|Mesoamerican writing system]]. The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the [[3rd century B.C.E.]],<ref>[http://sciencenow.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/2006/106/2 ''Science''] (subscription required)</ref> and writing was in continuous use until shortly after the arrival of the [[Spanish Empire|Spanish]] ''[[conquistador]]es'' in the 16th century CE (and even later in isolated areas such as [[Tayasal]]). Maya writing used [[logogram]]s complemented by a set of [[syllabary|syllabic]] [[glyph]]s, somewhat similar in function to modern [[Japanese writing]]. Maya writing was called "hieroglyphics" or "hieroglyphs" by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who did not understand it but found its general appearance reminiscent of [[Egyptian hieroglyph]]s, to which however the Maya writing system is not at all related. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Maya writing consisted of a highly elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls or bark-paper [[codex|codices]], carved in wood or stone, or molded in [[stucco]]. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has not often survived. | ||

| + | |||

| + | About three-quarters or more of Maya writing can now be read with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Maya script was a [[logogram|logosyllabic]] system. Individual symbols ("glyphs") could represent either a word (actually a [[morpheme]]) or a [[syllable]]; indeed, the same glyph could often be used for both. For example, the calendaric glyph <small>MANIK’</small> was also used to represent the syllable ''chi''. (It's customary to write logographic readings in all capitals and phonetic readings in italics.) It is possible, but not certain, that these conflicting readings arose as the script was adapted to new languages, as also happened with Japanese [[kanji]] and with Assyro-Babylonian and Hittite [[cuneiform]]. There was ambiguity in the other direction as well: Different glyphs could be read the same way. For example, half a dozen apparently unrelated glyphs were used to write the very common [[grammatical person|third person]] pronoun ''u-''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Maya was usually written in blocks arranged in columns two blocks wide, read as follows: | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Maya script reading direction.png|thumb|left|200px|Maya inscriptions were most often written in columns two glyphs wide, with each such column read left to right, top to bottom]] | ||

| + | [[Image:NaranjoStela10Maler.jpg|190px|right|thumb|An inscription in Maya glyphs from the site of [[Naranjo]], relating to the reign of king ''Itzamnaaj K'awil'', 784-810.]] | ||

| + | Within each block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right, superficially rather like Korean [[Hangul]] syllabic blocks. However, in the case of Maya, each block tended to correspond to a noun or verb [[phrase]] such as ''his green headband''. Also, glyphs were sometimes ''conflated,'' where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. Conflation occurs in other scripts: For example, in medieval Spanish manuscripts the word ''de'' 'of' was sometimes written Ð (a D with the arm of an E). A European example is the [[ampersand]] (&) which is a conflation of the Latin "et." In place of the standard block configuration Maya was also sometimes written in a single row or column, 'L', or 'T' shapes. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed. | ||

===Olmec hieroglyphs=== | ===Olmec hieroglyphs=== | ||

{{Main|Olmec hieroglyphs}} | {{Main|Olmec hieroglyphs}} | ||

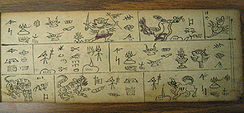

| + | [[Image:Cascajal-text.jpg|rught||260px|thumb|The 62 glyphs of the Cascajal Block]]The '''Cascajal Block''' is a writing tablet-sized [[serpentine]] slab which has been dated to the early first millennium B.C.E. incised with hitherto unknown characters that may represent the earliest [[writing system]] in the [[New World]]. Archaeologist [[Stephen D. Houston]] of [[Brown University]] said that this discovery helps to "link the [[Olmec]] civilization to literacy, document an unsuspected writing system, and reveal a new complexity to [the Olmec] civilization." | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in the late 1990s in a pile of debris in the village of Lomas de Tacamichapa in the [[Veracruz]] lowlands in the ancient [[Olmec heartland]]. The block was found amidst ceramic shards and clay figurines and from these the block is dated to the [[Olmec]] [[archaeological culture]]'s [[San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán]] phase, which ended c. 900 B.C.E. This means that the characters on the block are some 400 years older than any other [[Mesoamerican writing systems|writing known in the Western hemisphere]]. Archaeologists Carmen Rodriguez and Ponciano Ortiz of the [[National Institute of Anthropology and History]] of Mexico examined and registered it with government historical authorities. It weighs about 11.5 kg (25 lb) and measures 36 cm × 21 cm × 13 cm. Details of the find were published by researchers in the 15 September 2006 issue of the journal ''[[Science (journal)|Science]]''.<ref>In a paper entitled "Oldest Writing in the New World," see Rodríguez Martínez ''et al.'' (2006)</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Olmec flourished in the [[Gulf Coast of Mexico|Gulf Coast region of Mexico]], ca. 1250–400 B.C.E. The evidence for this writing system is based solely on the text on the Cascajal Block. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The block holds a total of 62 [[glyphs]], some of which resemble plants such as [[corn]] and [[ananas]], or animals such as insects and fish. Many of the symbols are more abstract boxes or blobs. The symbols on the Cascajal block are unlike those of any other writing system in Mesoamerica, such as in Mayan languages or [[Isthmian script|Isthmian]], another extinct Mesoamerican script. The Cascajal block is also unusual because the symbols apparently run in horizontal rows and "there is no strong evidence of overall organization. The sequences appear to be conceived as independent units of information".<ref>Quote taken from Rodríguez Martínez ''et al.'' (2006).</ref> All other known Mesoamerican scripts typically use vertical rows. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| Line 83: | Line 144: | ||

*Davies, William Vivian. 1990. "Egyptian Hieroglyphs." In ''Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet''. London: British Museum Press. 74–135. | *Davies, William Vivian. 1990. "Egyptian Hieroglyphs." In ''Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet''. London: British Museum Press. 74–135. | ||

| + | *W. C. Brice, ''Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: I. The Corpus. II. The Clay Bar from Malia, H20,'' Kadmos 29 (1990) 1-10. | ||

| + | *W. C. Brice, ''Cretan Hieroglyphs & Linear A'', Kadmos 29 (1990) 171-2. | ||

| + | *W. C. Brice, ''Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: III. The Inscriptions from Mallia Quarteir Mu. IV. The Clay Bar from Knossos, P116'', Kadmos 30 (1991) 93-104. | ||

| + | *W. C. Brice, ''Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script'', Kadmos 31 (1992), 21-24. | ||

| + | *J.-P. Olivier, L. Godard, in collaboration with J.-C. Poursat, ''Corpus Hieroglyphicarum Inscriptionum Cretae'' ''(CHIC)'', Études Crétoises 31, De Boccard, Paris 1996, ISBN 2-86958-082-7. | ||

| + | *[[Gareth Alun Owens|G. A. Owens]], ''The Common Origin of Cretan Hieroglyphs and Linear A'', Kadmos 35:2 (1996), 105-110. | ||

| + | *G. A. Owens, ''An Introduction to «Cretan Hieroglyphs»: A Study of «Cretan Hieroglyphic» Inscriptions in English Museums (excluding the Ashmolean Museum Oxford)'', Cretan Studies VIII (2002), 179-184. | ||

| + | *I. Schoep, ''A New Cretan Hieroglyphic Inscription from Malia (MA/V Yb 03)'', Kadmos 34 (1995), 78-80. | ||

| + | *J. G. Younger, ''The Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: A Review Article'', Minos 31-32 (1996-1997) 379-400. | ||

| + | |||

| + | *{{cite journal |author={{aut|Bruhns, Karen O.}} |coauthors={{aut|Nancy L. Kelker, Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, [[Michael D. Coe]], Richard A. Diehl, [[Stephen D. Houston]], [[Karl A. Taube]]}}, and {{aut|Alfredo Delgado Calderón}} |year=2007 |date=2007-03-09 |title=Did the Olmec Know How to Write? |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/citation/315/5817/1365b |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=315 |issue=5817 |pages=pp.1365–1366 |doi=10.1126/science.315.5817.1365b |location=Washington, DC|publisher=[[American Association for the Advancement of Science]]|issn=0036-8075 |oclc=206052590}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book |author={{aut|Houston, Stephen D.}} |authorlink=Stephen D. Houston |year=2004 |chapter=Writing in Early Mesoamerica |title=The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process |editor=Stephen D. Houston (ed.) |location=Cambridge |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |pages=pp.274–309 |isbn=0-521-83861-4 |oclc=56442696}} | ||

| + | * {{cite journal |author={{aut|Rodríguez Martínez, Ma. del Carmen}} |coauthors={{aut|Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, [[Michael D. Coe]], Richard A. Diehl, [[Stephen D. Houston]], [[Karl A. Taube]]}}, and {{aut|Alfredo Delgado Calderón}} |year=2006 |date=2006-09-16 |title=Oldest Writing in the New World |url=http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/313/5793/1610 |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=313 |issue=5793 |pages=pp.1610–1614 |doi=10.1126/science.1131492 |location=Washington, DC|publisher=[[American Association for the Advancement of Science]]|issn=0036-8075 |oclc=200349481}} | ||

| + | * {{cite web |author={{aut|Skidmore, Joel}} |year=2006 |title=The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing |url=http://www.mesoweb.com/reports/cascajal.html |format=[[PDF]] |work=Mesoweb Reports & News |publisher=Mesoweb |accessdate=2007-06-20}} | ||

| + | * {{cite book |author={{aut|Magni, Caterina}} |authorlink=Caterina Magni |year=2008 |chapter=Olmec Writing. The Cascajal Block: New Perspectives |title=Arts & Cultures 2008: Antiquité, Afrique, Océanie, Asie, Amérique |series=revue annuelle des musées Barbier-Mueller, 9 |editor=Laurence Mattet (ed.) |location=Paris, Genève/Barcelona |publisher=Somogy Éditions d'art, in collaboration with The Association of Friends of the [[Barbier-Mueller Museum]] |pages=pp.64–81 |isbn=978-2-7572-0163-3}} | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | *[http://people.ku.edu/~jyounger/Hiero/ The Cretan Hieroglyphic Texts] | ||

| + | |||

| + | *http://www.ancientscripts.com/luwian.html | ||

| + | *[http://indoeuro.bizland.com/project/script/luwia.html Luwian Hieroglyphics] from the Indo-European Database | ||

| + | *[http://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/luwglyph/Signlist.pdf Sign list], with logographic and syllabic readings | ||

| + | |||

| − | {{credits|173150695|Cursive_hieroglyphs|241581144|Dongba_script|255768794|||}} | + | *[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/5347080.stm “Oldest” New World writing found] by Helen Briggs for [[BBC News]], 14 September 2006. |

| + | *[http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2006-09/bu-owi091106.php Oldest writing in the New World discovered in Veracruz, Mexico] from EurekAlert, 14 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2006/09/15/MNGS8L68QT1.DTL 3,000-year-old script on stone found in Mexico] by John Noble Wilford for the [[New York Times]], 15 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://www.nytimes.com/2006/09/15/science/15writing.html?_r=2&oref=login&oref=slogin Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere] by John Noble Wilford for the [[New York Times]], 15 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6077734 Earliest New World Writing Discovered] by Christopher Joyce for [[NPR]], 15 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://www.scienceagogo.com/news/20060814215144data_trunc_sys.shtml Unknown Writing System Uncovered On Ancient Olmec Tablet] from Science a GoGo, 15 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://articles.news.aol.com/news/_a/stone-slab-bears-earliest-writing-in/20060914145609990007?ncid=NWS00010000000001 Stone Slab Bears Earliest Writing in Americas] by Andrew Bridges for AP, 15 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://www.evertype.com/gram/olmec.html Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs] by [[Michael Everson]], 18 September 2006. | ||

| + | *[http://mesoweb.com/reports/Cascajal.pdf The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing] Joel Skidmore, Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, <small>Accessed September 19 2006.<small> | ||

| + | {{credits|173150695|Cursive_hieroglyphs|241581144|Dongba_script|255768794|Cretan_hieroglyphs|253351258|Anatolian_hieroglyphs|252917179|Maya_script|251426098|Cascajal_Block255354058||}} | ||

Revision as of 16:28, 5 December 2008

A hieroglyph is a character of a logographic or partly logographic writing system. The term originally referred to the Egyptian hieroglyphs, but is also applied to the ancient Cretan Luwian, Mayan and Mi'kmaq scripts, and occasionally also to Chinese characters. It was also used by Ancient Egyptians. Ancient Egyptian writing consisted of over 2,000 hieroglyphic characters where as the English only consists of 26. Each hieroglyphic characters represent a common object from their day.

Etymology

The word Hieroglyphs derives from the Greek words ἱερός (hierós 'sacred') and γλύφειν (glúphein 'to carve' or 'to write', see glyph), and was first used to describe Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Greeks who came to Egypt prior to and during the Ptolemaic Period (305 B.C.E. - 30 B.C.E.) observed that while demotic script was employed for secular documents, pictorial characters were frequently found in religious contexts - carved on temple walls and funerary structures, as well as on official monuments.

The word "hieroglyphics" is derived from the fact that the Greeks called Egyptian hieroglyphs τά ἱερογλυφικά γράμματα 'hieroglyphic letters'; however, they sometimes simply dropped the word γράμματα, "letters," calling them τά ἱερογλυφικά 'the hieroglyphics' ('letters' being understood). This was used in informal use.

In the same way, although the term "hieroglyphics" is still used today, this usage adds a tone of informality (such as in the above example of Greek practice). An alternative is to use the noun "hieroglyphs" for both the language as a whole and for the individual characters that compose it, or to use the term "hieroglyphic" as an adjective (e.g., a hieroglyphic writing system).

Types

Egyptian hieroglyphs

Egyptian hieroglyphs (pronounced /ˈhaɪərəʊɡlɪf/; from Greek ἱερογλύφος "sacred carving," also hieroglyphic = τὰ ἱερογλυφικά [γράμματα]) was a formal writing system used by the ancient Egyptians that contained a combination of logographic and alphabetic elements. Egyptians used cursive hieroglyphs for religious literature on papyrus and wood. Less formal variations of the script, called hieratic and demotic, are technically not hieroglyphs. Hieroglyphs consist of three kinds of glyphs: phonetic glyphs, including single-consonant characters that functioned like an alphabet; logographs, representing morphemes; and determinatives, which narrowed down the meaning of a logographic or phonetic words.

Hieroglyphs emerged from the preliterate artistic traditions of Egypt. For example, symbols on Gerzean pottery from circa 4000 B.C.E. resemble hieroglyphic writing. For many years the earliest known hieroglyphic inscription was the Narmer Palette, found during excavations at Hierakonpolis (modern Kawm al-Ahmar) in the 1890s, which has been dated to circa 3200 B.C.E. However, in 1998 a German archaeological team under Günter Dreyer excavating at Abydos (modern Umm el-Qa'ab) uncovered tomb U-j of a Predynastic ruler, and recovered three hundred clay labels inscribed with proto-hieroglyphs, dating to the Naqada IIIA period of the 33rd century B.C.E.[1][2] The first full sentence written in hieroglyphs so far discovered was found on a seal impression found in the tomb of Seth-Peribsen at Umm el-Qa'ab, which dates from the Second Dynasty. In the era of the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom, about 800 hieroglyphs existed. By the Greco-Roman period, they numbered more than 5,000.[3]

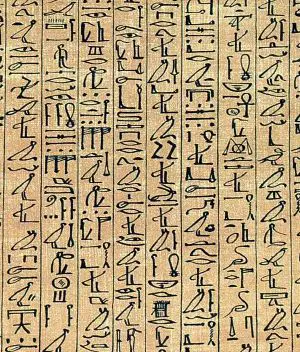

Cursive hieroglyphs

Cursive hieroglyphs are a variety of Egyptian hieroglyphs commonly used for religious documents written on papyrus, such as the Book of the Dead. It was particularly common during the Ramesside Period and many famous documents, such as the Papyrus of Ani, utilize it. It was also employed on wood for religious literature such as the Coffin Texts.

Cursive hieroglyphs should not be confused with hieratic. Hieratic is much more cursive, having large numbers of ligatures and signs unique to hieratic. However, there is, as might be expected, a certain degree of influence from hieratic in the visual appearance of some signs. One significant difference is that the orientation of cursive hieroglyphs is variable, reading right to left or left to right depending on the context, whereas hieratic is always read right to left.[4]

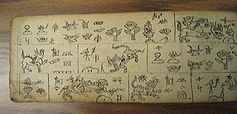

Dongba script

The Dongba, Tomba or Tompa script is a pictographic writing system used by the ²dto¹mba (Bon priests) of the Naxi people. In the Naxi language it is called ²ss ³dgyu 'wood records' or ²lv ³dgyu 'stone records'[5]. Together with the syllabic geba and the Latin alphabet, it is one of the three types of Naxi scripts. Dongba script is about a thousand years old. Although the glyphs look like crude pictographs that only represent simple materialistic objects, they are actually ideograms capable of representing abstract ideas. [6] Dongba writings are sometimes used as a rebus. It is a mnemonic system, and cannot by itself represent the Naxi language; different authors may use the same glyphs with different meanings, and it is often supplemented with the syllabic geba script for clarification.

|

|

The Dongba script is an independently developed ancient writing system. According to Dongba religious fables, the Dongba script was created by the founder of the Bön religious tradition of Tibet, Tönpa Shenrab (Tibetan: ston pa gshen rab) or Shenrab Miwo (Tibetan: gshen rab mi bo)[7]. Unfortunately, there is currently no accurate record of the exact date of the Dongba script origin and many suspected that the fables provided only fictional explanation to the foundation of this script. From Chinese historical documents, however, it is certain that Naxi script was used as early as the 7th century during the early Tang Dynasty. By the Song Dynastry in 10th century, Dongba script was widely used by the Naxi people.[8]

Cretan hieroglyphs

Cretan hieroglyphs are found on artifacts of Bronze Age Minoan Crete (early to mid 2nd millennium B.C.E., MM I to MM III, overlapping with Linear A from MM IIA at the earliest). Symbol inventories have been compiled by Evans (1909), Meijer (1982), Olivier/Godart (1996). The known corpus has been edited in 1996 as CHIC (Olivier/Godard 1996), listing a total of 314 items, mainly excavated at four locations:

- "Quartier Mu" at Malia (MM II)

- the hieroglyphic deposit at Malia palace (MM III)

- the hieroglyphic deposit at Knossos (MM II or III)

- the Petras deposit (MM IIB).

The corpus consists of:

- clay documents with incised inscriptions (CHIC H: 1-122)

- sealstone impressions (CHIC I: 123-179)

- sealstones (CHIC S: 180-314)

- the Malia altar stone

- the Phaistos Disk

- the Arkalochori Axe

- seal fragment HM 992, showing a single symbol, identical to Phaistos Disk glyph 21.

The relation of the last three items with the script of the main corpus is uncertain.

The glyph inventory as presented by CHIC consists of 96 syllabograms, ten of which double as logograms, an additional 23 logograms, 13 fractions (including 4 in ligature), four levels of numerals (units, tens, hundreds, thousands) and two types of punctuation. Many symbols have apparent Linear A counterparts, so that it is tempting to insert Linear B sound values.

Besides the supposed evolution of the hieroglyphs into the linear scripts, possible relations to Anatolian hieroglyphs were suggested, as well as to the Cypriot syllabary.

Anatolian hieroglyphs

Anatolian hieroglyphs are an indigenous logographic script native to central Anatolia, consisting of some 500 signs. They were once commonly known as Hittite hieroglyphs, but the language they encode proved to be Luwian, not Hittite, and the term Luwian hieroglyphs is used in English publications. They are typologically similar to Egyptian hieroglyphs, but do not derive graphically from that script, and they are not known to have played the sacred role of hieroglyphs in Egypt. There is no demonstrable connection to Hittite cuneiform.[9] [10] [11]

Anatolian hieroglyphs are attested from the third and second millennia BCE across Anatolia and into modern Syria. The earliest examples occur on personal seals, but these consist only of names, titles, and auspicious signs, and it is not certain that they represent language. Most actual texts are found as monumental inscriptions in stone, though a few documents have survived on lead strips.

The first monumental inscriptions confirmed as Luwian date to the Late Bronze Age, ca. 14th to 13th centuries B.C.E. And after some two centuries of sparse material the hieroglyphs resume in the Early Iron Age, ca. 10th to 8th centuries. In the early 7th century, the Luwian hieroglyphic script, by then aged some 1,300 years, falls into oblivion.

It is obvious that the script was designed for the Luwian language (notably because of the absence of an e series), which when used is known as Hieroglyphic Luwian, and no texts recording another language are known,[12] although there is occasionally foreign material like Hurrian theonyms, or glosses in Urartian (such as 500x33px á - ḫá+ra - ku for

100x33px aqarqi or 500x33px tu - ru - za for 100x33px ṭerusi, two units of measurement).

As in Egyptian, characters may be logographic or phonographic—that is, they may be used to represent words or sounds. The number of phonographic signs is limited. Most represent CV syllables, though there are a few disyllabic signs. A large number of these are ambiguous as to whether the vowel is a or i. Some signs are dedicated to one use or another, but many are flexible.

Words may be written logographically, phonetically, mixed (that is, a logogram with a phonetic complement), and may be preceded by a determinative. Other than the fact that the phonetic glyphs form a syllabary rather that indicating only consonants, this system is analogous to the system of Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Unlike Egyptian hieroglyphs, the lines of Luwian hieroglyphs are written alternately left-to-right and right-to-left. This practice was called by the Greeks boustrophedon, meaning "as the ox turns" (as when plowing a field).

Some scholars compare the Phaistos Disc and Cretan hieroglyphs as possibly related scripts, but there is no consensus regarding this.

Mayan hieroglyphs

The Maya script, also known as Maya hieroglyphs, was the writing system of the pre-Columbian Maya civilization of Mesoamerica, presently the only deciphered Mesoamerican writing system. The earliest inscriptions which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century B.C.E.,[13] and writing was in continuous use until shortly after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadores in the 16th century CE (and even later in isolated areas such as Tayasal). Maya writing used logograms complemented by a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Maya writing was called "hieroglyphics" or "hieroglyphs" by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who did not understand it but found its general appearance reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, to which however the Maya writing system is not at all related.

Maya writing consisted of a highly elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls or bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, or molded in stucco. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has not often survived.

About three-quarters or more of Maya writing can now be read with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure.

The Maya script was a logosyllabic system. Individual symbols ("glyphs") could represent either a word (actually a morpheme) or a syllable; indeed, the same glyph could often be used for both. For example, the calendaric glyph MANIK’ was also used to represent the syllable chi. (It's customary to write logographic readings in all capitals and phonetic readings in italics.) It is possible, but not certain, that these conflicting readings arose as the script was adapted to new languages, as also happened with Japanese kanji and with Assyro-Babylonian and Hittite cuneiform. There was ambiguity in the other direction as well: Different glyphs could be read the same way. For example, half a dozen apparently unrelated glyphs were used to write the very common third person pronoun u-.

Maya was usually written in blocks arranged in columns two blocks wide, read as follows:

Within each block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right, superficially rather like Korean Hangul syllabic blocks. However, in the case of Maya, each block tended to correspond to a noun or verb phrase such as his green headband. Also, glyphs were sometimes conflated, where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. Conflation occurs in other scripts: For example, in medieval Spanish manuscripts the word de 'of' was sometimes written Ð (a D with the arm of an E). A European example is the ampersand (&) which is a conflation of the Latin "et." In place of the standard block configuration Maya was also sometimes written in a single row or column, 'L', or 'T' shapes. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed.

Olmec hieroglyphs

The Cascajal Block is a writing tablet-sized serpentine slab which has been dated to the early first millennium B.C.E. incised with hitherto unknown characters that may represent the earliest writing system in the New World. Archaeologist Stephen D. Houston of Brown University said that this discovery helps to "link the Olmec civilization to literacy, document an unsuspected writing system, and reveal a new complexity to [the Olmec] civilization."

The Cascajal Block was discovered by road builders in the late 1990s in a pile of debris in the village of Lomas de Tacamichapa in the Veracruz lowlands in the ancient Olmec heartland. The block was found amidst ceramic shards and clay figurines and from these the block is dated to the Olmec archaeological culture's San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán phase, which ended c. 900 B.C.E. This means that the characters on the block are some 400 years older than any other writing known in the Western hemisphere. Archaeologists Carmen Rodriguez and Ponciano Ortiz of the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico examined and registered it with government historical authorities. It weighs about 11.5 kg (25 lb) and measures 36 cm × 21 cm × 13 cm. Details of the find were published by researchers in the 15 September 2006 issue of the journal Science.[14]

The Olmec flourished in the Gulf Coast region of Mexico, ca. 1250–400 B.C.E. The evidence for this writing system is based solely on the text on the Cascajal Block.

The block holds a total of 62 glyphs, some of which resemble plants such as corn and ananas, or animals such as insects and fish. Many of the symbols are more abstract boxes or blobs. The symbols on the Cascajal block are unlike those of any other writing system in Mesoamerica, such as in Mayan languages or Isthmian, another extinct Mesoamerican script. The Cascajal block is also unusual because the symbols apparently run in horizontal rows and "there is no strong evidence of overall organization. The sequences appear to be conceived as independent units of information".[15] All other known Mesoamerican scripts typically use vertical rows.

Mi'kmaq hieroglyphic writing

Chinese characters

Notes

- ↑ The origins of writing, Discovery Channel (1998-12-15)

- ↑ Richard Mattessich (Jun 2002) The oldest writings, and inventory tags of Egypt, The Accounting Historians Journal.

- ↑ Antonio Loprieno, Ancient Egyptian; A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, 1995 p.12

- ↑ Davies 1990:93

- ↑ He, 292

- ↑ He, 2008, p.146

- ↑ He, 144

- ↑ He, 144

- ↑ A. Payne, Hieroglyphic Luwian (2004), p. 1.

- ↑ Melchert, H. Craig. 2004. "Luvian," in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages, ed. Roger D. Woodard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56256-2

- ↑ Melchert, H. Craig. 1996. "Anatolian Hieroglyphs," in The World's Writing Systems, ed. Peter T. Daniels and William Bright. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0

- ↑ R. Plöchl, Einführung ins Hieroglyphen-Luwische (2003), p. 12.

- ↑ Science (subscription required)

- ↑ In a paper entitled "Oldest Writing in the New World," see Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2006)

- ↑ Quote taken from Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2006).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Robinson, Andrew. The story of writing with over 350 illustrations, 50 in color. New York: Thames & Hudson 2003. ISBN 0500281564

- Andrew Robinson (2007). Alphabets, Hieroglyphs and Pictograms, London: Thames & Hudson.

- Angelika Rauch (1997). The Hieroglyph of Tradition, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press.

- Douglas J (2007). Egypt and the Egyptians, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cruz-Uribe, Eugene. 2001. "Scripts: An Overview." In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald B. Redford. Vol. 3. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 192–198 [194–195].

- Davies, William Vivian. 1990. "Egyptian Hieroglyphs." In Reading the Past: Ancient Writing from Cuneiform to the Alphabet. London: British Museum Press. 74–135.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: I. The Corpus. II. The Clay Bar from Malia, H20, Kadmos 29 (1990) 1-10.

- W. C. Brice, Cretan Hieroglyphs & Linear A, Kadmos 29 (1990) 171-2.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: III. The Inscriptions from Mallia Quarteir Mu. IV. The Clay Bar from Knossos, P116, Kadmos 30 (1991) 93-104.

- W. C. Brice, Notes on the Cretan Hieroglyphic Script, Kadmos 31 (1992), 21-24.

- J.-P. Olivier, L. Godard, in collaboration with J.-C. Poursat, Corpus Hieroglyphicarum Inscriptionum Cretae (CHIC), Études Crétoises 31, De Boccard, Paris 1996, ISBN 2-86958-082-7.

- G. A. Owens, The Common Origin of Cretan Hieroglyphs and Linear A, Kadmos 35:2 (1996), 105-110.

- G. A. Owens, An Introduction to «Cretan Hieroglyphs»: A Study of «Cretan Hieroglyphic» Inscriptions in English Museums (excluding the Ashmolean Museum Oxford), Cretan Studies VIII (2002), 179-184.

- I. Schoep, A New Cretan Hieroglyphic Inscription from Malia (MA/V Yb 03), Kadmos 34 (1995), 78-80.

- J. G. Younger, The Cretan Hieroglyphic Script: A Review Article, Minos 31-32 (1996-1997) 379-400.

- Bruhns, Karen O. and Nancy L. Kelker, Ma. del Carmen Rodríguez Martínez, Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, and Alfredo Delgado Calderón (2007-03-09). Did the Olmec Know How to Write?. Science 315 (5817): pp.1365–1366.

- Houston, Stephen D. (2004). "Writing in Early Mesoamerica", in Stephen D. Houston (ed.): The First Writing: Script Invention as History and Process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp.274–309. ISBN 0-521-83861-4. OCLC 56442696.

- Rodríguez Martínez, Ma. del Carmen and Ponciano Ortíz Ceballos, Michael D. Coe, Richard A. Diehl, Stephen D. Houston, Karl A. Taube, and Alfredo Delgado Calderón (2006-09-16). Oldest Writing in the New World. Science 313 (5793): pp.1610–1614.

- Skidmore, Joel (2006). The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing (PDF). Mesoweb Reports & News. Mesoweb. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- Magni, Caterina (2008). "Olmec Writing. The Cascajal Block: New Perspectives", in Laurence Mattet (ed.): Arts & Cultures 2008: Antiquité, Afrique, Océanie, Asie, Amérique, revue annuelle des musées Barbier-Mueller, 9. Paris, Genève/Barcelona: Somogy Éditions d'art, in collaboration with The Association of Friends of the Barbier-Mueller Museum, pp.64–81. ISBN 978-2-7572-0163-3.

External links

- http://www.ancientscripts.com/luwian.html

- Luwian Hieroglyphics from the Indo-European Database

- Sign list, with logographic and syllabic readings

- “Oldest” New World writing found by Helen Briggs for BBC News, 14 September 2006.

- Oldest writing in the New World discovered in Veracruz, Mexico from EurekAlert, 14 September 2006.

- 3,000-year-old script on stone found in Mexico by John Noble Wilford for the New York Times, 15 September 2006.

- Writing May Be Oldest in Western Hemisphere by John Noble Wilford for the New York Times, 15 September 2006.

- Earliest New World Writing Discovered by Christopher Joyce for NPR, 15 September 2006.

- Unknown Writing System Uncovered On Ancient Olmec Tablet from Science a GoGo, 15 September 2006.

- Stone Slab Bears Earliest Writing in Americas by Andrew Bridges for AP, 15 September 2006.

- Analysis of Olmec Hieroglyphs by Michael Everson, 18 September 2006.

- The Cascajal Block: The Earliest Precolumbian Writing Joel Skidmore, Precolumbia Mesoweb Press, Accessed September 19 2006.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- 173150695 history

- 241581144 history

- 255768794 history

- 253351258 history

- 252917179 history

- 251426098 history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.