Difference between revisions of "Henotheism" - New World Encyclopedia

Scott Dunbar (talk | contribs) (importing and crediting from Wikipedia) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (43 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Status}} | |

| + | [[Category:Public]] | ||

| + | '''Henotheism''' (from the Greek ''heis theos'' or “one god”) refers to religious belief systems that accept the existence of many gods (such as [[polytheism]]) but worship one deity as supreme. Such belief systems have been found throughout history and across the world's cultures. The term was first coined by [[Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling]] (1775–1854) to describe what he thought to be an earlier stage to [[monotheism]], and was later brought into common usage by linguist [[Max Müller]] (1823–1900) in order to characterize religious beliefs found in the [[Vedas]] of [[Hinduism]]. Subsequently, anthropologist [[Edward Burnett Tylor]] (1832–1917) conceived of henotheism as a natural phase in the progression of religious development whereby cultures supposedly evolved from polytheism, through henotheism, to a culmination in monotheism as the supreme manifestation of religious thought. However, this evolutionary view of religion has generated much debate for it denies the position of the Abrahamic religions that God was monotheistic from the start. Nevertheless, the term henotheism continues to allow for greater precision in the classification of religious belief systems. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ==Henotheism as a Category of Religion== | ||

| − | + | "Henotheism" as a term is not widely used by the general public but it has featured prominently as a point of discussion in academic debates about the nature and development of religion. The [[academic study of religion]] distinguishes several categories of religious belief found throughout the world including [[monotheism]], [[polytheism]], [[deism]], [[pantheism]], and henotheism (among others). The term "henotheism" was used predominantly by linguists and anthropologists and has been associated with other academic categories of religion. For example, Max Müller used the term interchangeably with ''kathenotheism'' (from the Greek ''kath’hena,'' “one by one”), in reference to the Vedas where there are different supreme gods at different times. Similarly, henotheism should not be confused with [[monolatrism]], where many gods are believed to exist, but can only exert their power on those who worship them. While the monolator exclusively worships one god, the henotheist may worship any god within their specific [[pantheon (gods)|pantheon]], depending on various circumstances. | |

| − | === | + | ==Varieties of Henotheism found in Human Culture== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | The | + | ===Classical Greco-Roman Henotheism=== |

| + | Perhaps the most salient example of henotheism is found in the ancient cultures of classical Greece and Rome. Greco-Roman religion began as polytheism, but became thoroughly henotheistic over time. While the Greeks believed in multiple gods, each of whom took on specific roles or personalities, it was clear that [[Zeus]], god of the sky and thunder, was the superior deity, presiding over the Greek Olympic pantheon and fathering many of the other heroes and heroines. | ||

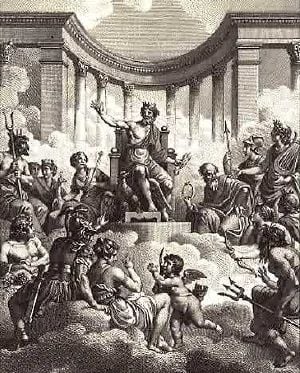

| + | [[Image:Olympians.jpg|thumb|left|The twelve gods of the Greek Olympic [[pantheon]] with Zeus at the center reigning supreme.]] | ||

| + | At first, [[Uranus]] was the supreme deity, until he became tyrannical and was usurped by his son [[Cronus]]. Cronus ruled during the mythological Golden Age, but became tyrannical himself, unwilling to give up his own position of supremacy to potential heirs. According to legend, Cronus swallowed each of his children when they were born but [[Rhea]], Uranus, and [[Gaia]] devised a plan to save Zeus. According to legend, Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Crete, and handed Cronus a rock wrapped in swaddling clothes, which Cronus promptly swallowed. In this manner, Zeus was spared. After reaching manhood, Zeus forced Cronus to disgorge the other children and overthrew Cronus thereby ascending to the throne as the supreme god. | ||

| − | + | When the Roman state assumed control of Greece in 146 B.C.E., it assimilated many of the local Greek gods into the Roman pantheon. Roman religion was similar to Greek religion in regards to its henotheistic framework. Early Roman divinities included a host of specialized gods whose names were called upon in the performance of various practical duties of daily Roman life. For example, [[Janus]] and [[Vesta]] watched over the door and hearth, [[Saturn (Greek God)]] the sowing, [[Lares]] the field and house, [[Pales]] the pasture, [[Ceres]] the growth of the grain, [[Pomon]] the fruit, and [[Consus]] and [[Ops]] the harvest. Certain gods came to primacy over the others, though. At the head of the earliest pantheon was the triad of [[Mars (Greek God)]], [[Quirinus]], and [[Jupiter (Greek God)]], whose three priests, or flamens, were of the highest order. Mars was a god of youthful men and their activities, especially war, while Quirinus is thought to have been the patron of the armed contingent in times of peace. Jupiter, however, was clearly given primacy over all the others as ruler of the gods. Like [[Zeus]], he wielded a weapon of lightning and was considered the director of human activity. By way of his widespread domain, Jupiter was the protector of the Romans in their military activities beyond the borders of their own community. Upon Roman entry into the neighboring Greek territory, the Romans promptly identified their important deities with the Greek pantheon, and borrowed heavily from the myths and characteristics of the Greek gods and goddesses in order to enrich their own religion. These henotheistic beliefs were upheld until [[Christianity]] superseded the native religions of the [[Roman Empire]]. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | ===Israelite and Judaic Beliefs=== | ||

| − | + | It is generally accepted that many of the Iron Age religions found in Israel were henotheistic in practice. For example, the [[Moab|Moabites]] worshipped the god [[Chemosh]], and the [[Edom|Edomites]], [[Qaus]], both of whom were part of the greater [[Canaan|Canaanite]] pantheon, headed by the chief gods, [[El (Canaanite god)|El]] and [[Asherah]]. They had 70 sons between them who were said to rule over each of the nations of the earth, and became national gods worshipped in each region. More recently, M.S. Smith's synthesis of the [[Hebrews|Hebrew]] culture in the Iron Age has put forth the thesis that Hebrew religion, like those around it, was henotheistic. The discovery of artifacts at Kuntillet 'Ajrud and Khirbet El-Qom suggest that in at least some sections of Israelite society, [[Yahweh]] and Asherah were believed to coexist as a divine couple. Further evidence of an understanding of Yahweh existing within the Canaanite pantheon derives from syncretistic [[Mythology|myths]] found within the [[Hebrew Bible]] itself. Various battles between Yahweh and [[Leviathan]], [[Mot]], the [[Tannin|Tanninim]], and [[Yamm]] are already presented in the fourteenth-century B.C.E. texts found at [[Ugarit]] (ancient Ras-Shamra). In some cases, Yahweh had replaced [[Baal]], and in others, he had assumed El's roles. | |

| − | + | According to the [[Book of Genesis]], the [[prophet]] [[Abraham]] is revered as the individual who overcame the idol worship of his family and surrounding peoples by recognizing the Hebrew God and establishing a covenant with Him. In addition, he laid the foundations for what has been called by scholars "[[Ethical Monotheism]]." The first of the [[Decalogue|Ten Commandments]] is commonly interpreted to forbid the Israelites from worshiping any god other than the one true God who had given them the [[Torah]]. However, this commandment has also been interpreted as a evidence of henotheism, since the Hebrew God states that the Israelites should have "no other gods before me" and thus insinuates the existence of other gods. Against the Torah's teachings, the patron god [[Tetragrammaton|YHWH]] was frequently worshipped in conjunction with other gods such as [[Baal]], [[Asherah]], and [[El (Canaanite god)|El]]. Over time, this tribal god may have assumed all the appellations of the other gods in the eyes of the people. The destruction of the [[Jewish Temple in Jerusalem]] and the exile to Babylon was considered a divine reprimand and punishment for the mistaken worship of other deities. Thus, by the end of the [[Babylonian captivity of Judah]] in the [[Tanakh]], Judaism is strictly [[monotheism|monotheistic]]. | |

===Christianity=== | ===Christianity=== | ||

| − | |||

| − | The Christian | + | Christians consider themselves to be [[monotheism|monotheists]], but some observers have argued that [[Christianity]] may plausibly be described as an example of henotheism for several reasons. First, the Christian belief in the Holy [[Trinity]] has been seen as a type of polytheism or henotheism. The doctrine of the Holy Trinity claims that God consists of three equal "persons" (Greek ''[[Hypostasis]]'') having a single "substance" (Greek ''Ousia''), thus counting as one God; yet, some early Christian groups, such as the [[Ebionites]] or [[Docities]], were eventually labeled as heretical because they worshipped the Father as the supreme God, and saw Jesus as merely an apparition or a perfect man. Traditional Christian doctrine rejects the view that the "three persons" of the Trinity are distinct gods. |

| − | + | Nevertheless, several [[non-Trinitarian]] Christian denominations are more overtly henotheistic. For example, [[The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints]] (Mormonism, or the LDS Church) views the members of the [[Godhead (Christianity)|Christian Godhead]] as three distinct beings, where [[God the Father]] is supreme. Though not explicitly mentioned in canonical LDS scripture, some [[Latter Day Saint]]s also infer the existence of numerous other [[god]]s and [[goddess]]es who have no direct relevance to humanity on Earth. Some Latter Day Saints also acknowledge a [[Heavenly Mother]] in addition to God the Father. However, Mormons worship one God; this view is most easily described as worshipping God the Father through the conduit of the Son, Jesus Christ. Whereas other Christians speak of "One God in Three Persons," the LDS scripture speaks instead of three persons in one God. | |

| − | + | Finally, some Christians revere a "pantheon" of [[angel]]s and [[saint]]s that are inferior to the [[Trinity]]. For example, [[Mother Mary]] is widely revered as an intercessor between God and humanity in the Roman Catholic Church. Christians do not label these beings as "gods," although they are attributed with supernatural powers and occasionally serve as the objects of prayer. Thus some non-Christians think Christianity is henotheistic. | |

| − | + | ===Hinduism=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | Early Vedic [[Hinduism]] is considered to be one of the best examples of henotheism in the world's religions. Although Hinduism contains many different kinds of beliefs including [[monism]], [[polytheism]], and [[atheism]], the earliest Hindu [[scriptures]], known as the [[Vedas]], worship many gods but hail one as supreme. Usually, this supreme God was called Indra but various cosmic forces such as [[Agni]], god of fire, [[Varuna]], keeper of the celestial waters, and [[Vac]], speech, were also revered. Each of these gods was hailed as supreme in different sections of the Vedas, and paralleling the [[mythology]] of the Greeks, the Vedic gods also underwent their own battles for supremacy. In pre-Vedic times, Varuna was the supreme lord of the cosmos; however, in the Vedas, he is supplanted by [[Indra]] as king of the gods. Over time, however, Hinduism changed and the powers of Indra were usurped by other deities, such as [[Vishnu]] and [[Shiva]], who in turn were absorbed into a larger philosophical framework of monism in later Hinduism. Hindu phrases such as ''Ekam Sat, Vipraha Bahudha Vadanti'' (Truth is One, though the sages know it as many) provides additional evidence that the Vedic people identified a fundamental oneness beyond the personalities of their many gods. Based on this mixture of monism, [[monotheism]], and polytheism, [[Max Muller|Max Müller]] decided that henotheism was the most suitable classification for Vedic Hinduism. Whether the term of henotheism adequately addresses these complexities still remains a matter of contention. The term may underestimate the idea of pure monism which can be identified even in the early [[Rig Veda]] [[Samhita]], notwithstanding clearly monist and monotheistic movements of Hinduism that developed with the advent of the [[Upanishads]]. | |

| − | + | While the Vedic period of Hinduism most closely corresponds to henotheism as Müller understood it, more subtle manifestations of henotheism can be discerned within the later traditions. Medieval Hinduism saw the emergence of devotional sects with the onset of the essentially monotheistic [[bhakti]] (loving devotion) movement. The rise of scriptures called the [[Puranas]], focused on particular gods such as Shiva and Vishnu. These scriptures, while admitting the existence of other deities, saw the particular deity of their choice as often superior, yet derivative from one principal source. As a result, different devotional traditions have disputed the relative importance of various gods, some insisting on the primacy of Shiva over Vishnu and vice-versa, for example. Extreme monists within the [[Advaita Vedanta]] movement, [[Yoga]] philosophy, and certain non-dual [[Tantra]] schools of Hinduism seem to preclude the categorization of Hinduism as henotheistic. Yet, popular Hinduism is widely centered on worship of the Hindu trinity, [[Brahma (god)|Brahma]], Vishnu, and Shiva, gods which respectively represent creation, preservation, and destruction in one cycle of being. Today, Goddess worship ([[shakti]]) has replaced worship of Brahma. Again, "henotheism" proves to be a pliable term which can serve to clarify such ambiguities in vast, multifarious religious systems such as Hinduism. | |

| − | == | + | ==Significance of Henotheism== |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Henotheism is an important classification in religious scholarship, since it nuances forms of worship which might otherwise be labeled under the general headings of [[monotheism]] or [[polytheism]]. It provides a classification for those religious communities who worship many gods but elevate one god as supreme. The term "henotheism" is particularly helpful in understanding ancient religious and mythological systems based on narratives that bring one god into primacy among others. The term possesses historical significance, as numerous major religious systems of contemporary times passed through phases of henotheistic thought. Although Tylor’s theory purporting a progression of religion from “simple” polytheism to more developed monotheism, with henotheism serving as the middle stage, has generally been rejected, it remains a valued category in religious discourse. |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [ | + | ==References== |

| − | [ | + | * Mico, Vincent. [http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Delphi/8991/roman.html "Roman Mythology."] Retrieved March 17, 2006. |

| − | [ | + | * [http://www.pantheon.org/articles/v/varuna.html "Varuna."] Encyclopedia Mythica Online. Retrieved March 10, 2006. |

| − | + | * [http://www.pantheon.org/articles/i/indra.html "Indra"] Encyclopedia Mythica Online. Retrieved March 10, 2006. | |

| − | [ | + | * "Henotheism." ''Encyclopedia of Religion,'' ed. Mercia Eliade. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987. |

| − | + | * [http://www.webcom.com/gnosis/gnintro.htm "The Gnostic Worldview: A Brief Summary of Gnosticism."] Retrieved March 10, 2006. | |

| − | + | * Smith, Mark S. ''The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities in Ancient Israel,'' 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdman's, 2002. | |

| + | * "Monotheism." ''Encyclopedia Britannica''. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Christian theology]] | |

| − | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | |

| − | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]][[category:Religion]] | + | [[category:Religion]] |

| − | + | {{credit|41751061}} | |

Latest revision as of 15:20, 25 January 2023

Henotheism (from the Greek heis theos or “one god”) refers to religious belief systems that accept the existence of many gods (such as polytheism) but worship one deity as supreme. Such belief systems have been found throughout history and across the world's cultures. The term was first coined by Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling (1775–1854) to describe what he thought to be an earlier stage to monotheism, and was later brought into common usage by linguist Max Müller (1823–1900) in order to characterize religious beliefs found in the Vedas of Hinduism. Subsequently, anthropologist Edward Burnett Tylor (1832–1917) conceived of henotheism as a natural phase in the progression of religious development whereby cultures supposedly evolved from polytheism, through henotheism, to a culmination in monotheism as the supreme manifestation of religious thought. However, this evolutionary view of religion has generated much debate for it denies the position of the Abrahamic religions that God was monotheistic from the start. Nevertheless, the term henotheism continues to allow for greater precision in the classification of religious belief systems.

Henotheism as a Category of Religion

"Henotheism" as a term is not widely used by the general public but it has featured prominently as a point of discussion in academic debates about the nature and development of religion. The academic study of religion distinguishes several categories of religious belief found throughout the world including monotheism, polytheism, deism, pantheism, and henotheism (among others). The term "henotheism" was used predominantly by linguists and anthropologists and has been associated with other academic categories of religion. For example, Max Müller used the term interchangeably with kathenotheism (from the Greek kath’hena, “one by one”), in reference to the Vedas where there are different supreme gods at different times. Similarly, henotheism should not be confused with monolatrism, where many gods are believed to exist, but can only exert their power on those who worship them. While the monolator exclusively worships one god, the henotheist may worship any god within their specific pantheon, depending on various circumstances.

Varieties of Henotheism found in Human Culture

Classical Greco-Roman Henotheism

Perhaps the most salient example of henotheism is found in the ancient cultures of classical Greece and Rome. Greco-Roman religion began as polytheism, but became thoroughly henotheistic over time. While the Greeks believed in multiple gods, each of whom took on specific roles or personalities, it was clear that Zeus, god of the sky and thunder, was the superior deity, presiding over the Greek Olympic pantheon and fathering many of the other heroes and heroines.

At first, Uranus was the supreme deity, until he became tyrannical and was usurped by his son Cronus. Cronus ruled during the mythological Golden Age, but became tyrannical himself, unwilling to give up his own position of supremacy to potential heirs. According to legend, Cronus swallowed each of his children when they were born but Rhea, Uranus, and Gaia devised a plan to save Zeus. According to legend, Rhea gave birth to Zeus in Crete, and handed Cronus a rock wrapped in swaddling clothes, which Cronus promptly swallowed. In this manner, Zeus was spared. After reaching manhood, Zeus forced Cronus to disgorge the other children and overthrew Cronus thereby ascending to the throne as the supreme god.

When the Roman state assumed control of Greece in 146 B.C.E., it assimilated many of the local Greek gods into the Roman pantheon. Roman religion was similar to Greek religion in regards to its henotheistic framework. Early Roman divinities included a host of specialized gods whose names were called upon in the performance of various practical duties of daily Roman life. For example, Janus and Vesta watched over the door and hearth, Saturn (Greek God) the sowing, Lares the field and house, Pales the pasture, Ceres the growth of the grain, Pomon the fruit, and Consus and Ops the harvest. Certain gods came to primacy over the others, though. At the head of the earliest pantheon was the triad of Mars (Greek God), Quirinus, and Jupiter (Greek God), whose three priests, or flamens, were of the highest order. Mars was a god of youthful men and their activities, especially war, while Quirinus is thought to have been the patron of the armed contingent in times of peace. Jupiter, however, was clearly given primacy over all the others as ruler of the gods. Like Zeus, he wielded a weapon of lightning and was considered the director of human activity. By way of his widespread domain, Jupiter was the protector of the Romans in their military activities beyond the borders of their own community. Upon Roman entry into the neighboring Greek territory, the Romans promptly identified their important deities with the Greek pantheon, and borrowed heavily from the myths and characteristics of the Greek gods and goddesses in order to enrich their own religion. These henotheistic beliefs were upheld until Christianity superseded the native religions of the Roman Empire.

Israelite and Judaic Beliefs

It is generally accepted that many of the Iron Age religions found in Israel were henotheistic in practice. For example, the Moabites worshipped the god Chemosh, and the Edomites, Qaus, both of whom were part of the greater Canaanite pantheon, headed by the chief gods, El and Asherah. They had 70 sons between them who were said to rule over each of the nations of the earth, and became national gods worshipped in each region. More recently, M.S. Smith's synthesis of the Hebrew culture in the Iron Age has put forth the thesis that Hebrew religion, like those around it, was henotheistic. The discovery of artifacts at Kuntillet 'Ajrud and Khirbet El-Qom suggest that in at least some sections of Israelite society, Yahweh and Asherah were believed to coexist as a divine couple. Further evidence of an understanding of Yahweh existing within the Canaanite pantheon derives from syncretistic myths found within the Hebrew Bible itself. Various battles between Yahweh and Leviathan, Mot, the Tanninim, and Yamm are already presented in the fourteenth-century B.C.E. texts found at Ugarit (ancient Ras-Shamra). In some cases, Yahweh had replaced Baal, and in others, he had assumed El's roles.

According to the Book of Genesis, the prophet Abraham is revered as the individual who overcame the idol worship of his family and surrounding peoples by recognizing the Hebrew God and establishing a covenant with Him. In addition, he laid the foundations for what has been called by scholars "Ethical Monotheism." The first of the Ten Commandments is commonly interpreted to forbid the Israelites from worshiping any god other than the one true God who had given them the Torah. However, this commandment has also been interpreted as a evidence of henotheism, since the Hebrew God states that the Israelites should have "no other gods before me" and thus insinuates the existence of other gods. Against the Torah's teachings, the patron god YHWH was frequently worshipped in conjunction with other gods such as Baal, Asherah, and El. Over time, this tribal god may have assumed all the appellations of the other gods in the eyes of the people. The destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem and the exile to Babylon was considered a divine reprimand and punishment for the mistaken worship of other deities. Thus, by the end of the Babylonian captivity of Judah in the Tanakh, Judaism is strictly monotheistic.

Christianity

Christians consider themselves to be monotheists, but some observers have argued that Christianity may plausibly be described as an example of henotheism for several reasons. First, the Christian belief in the Holy Trinity has been seen as a type of polytheism or henotheism. The doctrine of the Holy Trinity claims that God consists of three equal "persons" (Greek Hypostasis) having a single "substance" (Greek Ousia), thus counting as one God; yet, some early Christian groups, such as the Ebionites or Docities, were eventually labeled as heretical because they worshipped the Father as the supreme God, and saw Jesus as merely an apparition or a perfect man. Traditional Christian doctrine rejects the view that the "three persons" of the Trinity are distinct gods.

Nevertheless, several non-Trinitarian Christian denominations are more overtly henotheistic. For example, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormonism, or the LDS Church) views the members of the Christian Godhead as three distinct beings, where God the Father is supreme. Though not explicitly mentioned in canonical LDS scripture, some Latter Day Saints also infer the existence of numerous other gods and goddesses who have no direct relevance to humanity on Earth. Some Latter Day Saints also acknowledge a Heavenly Mother in addition to God the Father. However, Mormons worship one God; this view is most easily described as worshipping God the Father through the conduit of the Son, Jesus Christ. Whereas other Christians speak of "One God in Three Persons," the LDS scripture speaks instead of three persons in one God.

Finally, some Christians revere a "pantheon" of angels and saints that are inferior to the Trinity. For example, Mother Mary is widely revered as an intercessor between God and humanity in the Roman Catholic Church. Christians do not label these beings as "gods," although they are attributed with supernatural powers and occasionally serve as the objects of prayer. Thus some non-Christians think Christianity is henotheistic.

Hinduism

Early Vedic Hinduism is considered to be one of the best examples of henotheism in the world's religions. Although Hinduism contains many different kinds of beliefs including monism, polytheism, and atheism, the earliest Hindu scriptures, known as the Vedas, worship many gods but hail one as supreme. Usually, this supreme God was called Indra but various cosmic forces such as Agni, god of fire, Varuna, keeper of the celestial waters, and Vac, speech, were also revered. Each of these gods was hailed as supreme in different sections of the Vedas, and paralleling the mythology of the Greeks, the Vedic gods also underwent their own battles for supremacy. In pre-Vedic times, Varuna was the supreme lord of the cosmos; however, in the Vedas, he is supplanted by Indra as king of the gods. Over time, however, Hinduism changed and the powers of Indra were usurped by other deities, such as Vishnu and Shiva, who in turn were absorbed into a larger philosophical framework of monism in later Hinduism. Hindu phrases such as Ekam Sat, Vipraha Bahudha Vadanti (Truth is One, though the sages know it as many) provides additional evidence that the Vedic people identified a fundamental oneness beyond the personalities of their many gods. Based on this mixture of monism, monotheism, and polytheism, Max Müller decided that henotheism was the most suitable classification for Vedic Hinduism. Whether the term of henotheism adequately addresses these complexities still remains a matter of contention. The term may underestimate the idea of pure monism which can be identified even in the early Rig Veda Samhita, notwithstanding clearly monist and monotheistic movements of Hinduism that developed with the advent of the Upanishads.

While the Vedic period of Hinduism most closely corresponds to henotheism as Müller understood it, more subtle manifestations of henotheism can be discerned within the later traditions. Medieval Hinduism saw the emergence of devotional sects with the onset of the essentially monotheistic bhakti (loving devotion) movement. The rise of scriptures called the Puranas, focused on particular gods such as Shiva and Vishnu. These scriptures, while admitting the existence of other deities, saw the particular deity of their choice as often superior, yet derivative from one principal source. As a result, different devotional traditions have disputed the relative importance of various gods, some insisting on the primacy of Shiva over Vishnu and vice-versa, for example. Extreme monists within the Advaita Vedanta movement, Yoga philosophy, and certain non-dual Tantra schools of Hinduism seem to preclude the categorization of Hinduism as henotheistic. Yet, popular Hinduism is widely centered on worship of the Hindu trinity, Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, gods which respectively represent creation, preservation, and destruction in one cycle of being. Today, Goddess worship (shakti) has replaced worship of Brahma. Again, "henotheism" proves to be a pliable term which can serve to clarify such ambiguities in vast, multifarious religious systems such as Hinduism.

Significance of Henotheism

Henotheism is an important classification in religious scholarship, since it nuances forms of worship which might otherwise be labeled under the general headings of monotheism or polytheism. It provides a classification for those religious communities who worship many gods but elevate one god as supreme. The term "henotheism" is particularly helpful in understanding ancient religious and mythological systems based on narratives that bring one god into primacy among others. The term possesses historical significance, as numerous major religious systems of contemporary times passed through phases of henotheistic thought. Although Tylor’s theory purporting a progression of religion from “simple” polytheism to more developed monotheism, with henotheism serving as the middle stage, has generally been rejected, it remains a valued category in religious discourse.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mico, Vincent. "Roman Mythology." Retrieved March 17, 2006.

- "Varuna." Encyclopedia Mythica Online. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- "Indra" Encyclopedia Mythica Online. Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- "Henotheism." Encyclopedia of Religion, ed. Mercia Eliade. New York: MacMillan Publishing, 1987.

- "The Gnostic Worldview: A Brief Summary of Gnosticism." Retrieved March 10, 2006.

- Smith, Mark S. The Early History of God: Yahweh and Other Deities in Ancient Israel, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdman's, 2002.

- "Monotheism." Encyclopedia Britannica.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.