Girondins

Girondins | |

| Leader | Marquis de Condorcet Jean-Marie Roland Jacques Pierre Brissot Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1791 |

| Dissolved | 1793 |

| Headquarters | Bordeaux, Gironde |

| Newspaper | Patriote français Le Courrier de Provence La chronique de Paris |

| Ideology | Abolitionism[1] Republicanism Classical liberalism Economic liberalism |

| Colors | Blue |

The Girondins (US: /(d)ʒɪˈrɒndɪnz/ ji-RON-dinz, zhi-,[2] French: [ʒiʁɔ̃dɛ̃], or Girondists, were a group of loosely affiliated individuals rather than an organized political party and the name was at first informally applied because the most prominent exponents of their point of view were deputies to the Legislative Assembly originally from the département of Gironde in southwest France. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were leading figures in the Legislative Assembly and its successor, the National Convention. Girondin leader Jacques Pierre Brissot proposed an ambitious military plan to spread the Revolution internationally, therefore the Girondins were the war party in 1792–1793. Other prominent Girondins included Jean Marie Roland and his wife Madame Roland. They also had an ally in the English-born American activist Thomas Paine.

Like the Montagnards, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy, but then after the overthrow of Louis XVI, they resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the National Convention until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of Girondin leaders. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

Identity

The collective name "Girondins" is used to describe "a loosely knit group of French deputies who contested the Montagnards for control of the National Convention."[3] They were never an official organization or political party.[4][5] The name itself was bestowed not by those who were reputed to be members but by the Montagnards, "who claimed as early as April 1792 that a counterrevolutionary faction had coalesced around deputies of the department of the Gironde."[6][7] Jacques-Pierre Brissot, Jean Marie Roland and François Buzot were among their most prominent deputies. Their contemporaries called their supporters Brissotins, Rolandins, or Buzotins, depending on which politician was under attack for their leadership. Other names were employed at the time too, but "Girondins" ultimately became the term favored by historians.[8] The term became standard with Alphonse de Lamartine's History of the Girondins in 1847.[9]

Political ideology

Influenced by classical liberalism and the concepts of democracy, human rights and Montesquieu's separation of powers, the Girondins initially supported a constitutional monarchy, but after the Flight to Varennes in which Louis XVI tried to flee Paris in the face of growing attacks, and purportedly in order to start a counter-revolution, the Girondins became mostly republicans, with a royalist minority. Like the Jacobins, they were also influenced by the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[10]

During its early period of the majority in the government, the Gironde supported a free market - opposing price controls on goods such as a 1793 maximum on grain prices[11] while also supporting a constitutional right to public assistance for the poor and public education. Under the leadership of Brissot, they advocated exporting the Revolution through aggressive foreign policies including war against the surrounding European monarchies.[12] The Girondins were also one of the first supporters of abolitionism in France with Brissot leading the anti-slavery Society of the Friends of the Blacks.[13] Certain Girondins such as Condorcet supported women's suffrage and political equality.

Originally they sat to the left of the centrist[14] Feuillants, but later, as the Revolution moved further left, sat on the right of the National Assembly after the neutralization of the Feuillants.[15] They became the principal conservative political party in France after the August 10, 1792 insurrection opposing the radical course of the revolution which lead to the Reign of Terror.[16] Generally, historians divide the Convention into the left-wing Jacobin Montagnards, the centrist The Plain and the right-wing Girondins.[17]

The Girondins supported democratic reform, secularism and a strong legislature at the expense of a weaker executive and judiciary as opposed to the authoritarian left-wing Montagnards, who supported public acknowledgement of a Supreme Being and a strong executive.[18]

History

Rise

Twelve deputies represented the département of the Gironde. There were six who sat for this département in both the Legislative Assembly of 1791–1792 and the National Convention of 1792–1795. Five were lawyers: Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud, Marguerite-Élie Guadet, Armand Gensonné, Jean Antoine Laffargue de Grangeneuve and Jean Jay (who was also a Protestant pastor). The other, Jean François Ducos, was a tradesman. In the Legislative Assembly, they represented a compact body of opinion which, though not as yet definitely republican (i.e. against the monarchy), was considerably more "advanced" than the moderate royalism of the majority of the Parisian deputies.

A group of deputies from elsewhere became associated with these views, most notably the Marquis de Condorcet, Claude Fauchet, Marc David Lasource, Maximin Isnard, the Comte de Kersaint, Henri Larivière and above all [[Jacques Pierre Brissot, Jean Marie Roland and Jérôme Pétion, who was elected mayor of Paris to succeed Jean Sylvain Bailly on November 16, 1791.

Madame Roland, whose salon became their gathering place, had a powerful influence on the spirit and policy of the Girondins with her "romantic republicanism."[19] The party cohesion they possessed was connected to the energy of Brissot, who came to be regarded as their mouthpiece in the Assembly and in the Jacobin Club, hence the name "Brissotins" for his followers.[20] The terms by which the group was identified by its enemies at the start of the National Convention (September 20, 1792), "Brissotins" and "Girondins," were terms of opprobrium used by their enemies in a separate faction of the Jacobin Club, who freely denounced them as enemies of democracy.

Foreign policy

In the Legislative Assembly, the Girondins represented the principle of democratic revolution within France and patriotic defiance to the European powers. They supported an aggressive foreign policy and constituted the war party in the period 1792–1793, when revolutionary France initiated a long series of revolutionary wars with other European powers. Brissot proposed an ambitious military plan to spread the Revolution internationally, one that Napoleon later pursued aggressively.[21] Brissot called on the National Convention to dominate Europe by conquering the Rhineland, Poland and the Netherlands with a goal of creating a protective ring of satellite republics in Great Britain, Spain and Italy by 1795. The Girondins also called for war against Austria, arguing it would rally patriots around the Revolution, liberate oppressed peoples from despotism, and test the loyalty of King Louis XVI whose wife, Marie Antoinette was Austrian.[22]

Montagnards versus Girondins

Girondins dominated the Jacobin Club in the early years of the Revolution. Brissot's influence had not yet been ousted by Maximilien Robespierre.[23] They did not hesitate to use this advantage to stir up popular passion and intimidate those who sought to stay the progress of the Revolution. They compelled the king in 1792 to choose a ministry composed of their partisans, among them Roland, Charles François Dumouriez,[24] Étienne Clavière and Joseph Marie Servan de Gerbey. They forced a declaration of war against Habsburg Austria the same year. In all of this activity, there was no apparent political distance between La Gironde and The Mountain. Montagnards and Girondins alike were fundamentally opposed to the monarchy; both were democrats as well as republicans. Both were prepared to appeal to force in order to realize their goals. Despite accusations of "federalism," by which their opponents meant wanting to weaken the central government, the Girondins desired as little as the Montagnards to break up the unity of France.[25]

Temperament largely accounts for the division between the parties. The Girondins were doctrinaires and theorists rather than men of action, favored by government officials and business while the Montagnards were the representatives of the sans culottes and Paris Commune. The Girondins initially encouraged armed petitions, but then were dismayed when this led to the émeute (riot) of 20 June 1792. Jean-Marie Roland was typical of their spirit, turning the Ministry of the Exterior into a publishing office for tracts on civic virtues while riotous mobs were burning the châteaux unchecked in the provinces. Girondins did not share the ferocious fanaticism or the ruthless opportunism of the future Montagnard organizers of the Reign of Terror. As the Revolution developed, the Girondins found themselves opposing some of its more radical results; the overthrow of the monarchy on August 10, 1792 and the September Massacres of 1792 occurred while they still nominally controlled the government, but it was not their work and they tried to distance themselves from its terrible results. They "endeavored to use the deaths as a stick with which to attack their enemies among the Jacobins."[26]

When the National Convention, successor to the Legislative Assembly, first met on September 22, 1792, the core of like-minded deputies from the Gironde expanded as Jean-Baptiste Boyer-Fonfrède, Jacques Lacaze and François Bergoeing joined five of the six stalwarts of the Legislative Assembly (Jean Jay, the Protestant pastor, drifted toward the Montagnard faction). Their numbers were increased by the return to national politics by former National Constituent Assembly deputies such as Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne, Pétion and Kervélégan, as well as some newcomers like the writer Thomas Paine and popular journalist Jean Louis Carra.

Decline

The Girondins proposed suspending the king and summoning the National Convention, but they agreed not to overthrow the monarchy until Louis XVI became impervious to their counsels. Once the king was overthrown in 1792 by a mob organized by Jean-Paul Marat and the Paris Commune, a republic was established to take its place. At this point they were anxious to halt further radicalization in the revolutionary movement that they had helped to set in motion. Historian Pierre Claude François Daunou argues in his Mémoires that the Girondins were too cultivated and too polished to retain their popularity for long in times of the poltical chaos that followed the fall of the monarchy. They were more inclined to work for the establishment of order, which had the added benefit of guaranteeing their own power. The Girondins, who had been the radicals of the Legislative Assembly (1791–1792), became the conservatives of the Convention (1792–1795) as the Commune and the more radical elements of the Jacobin club became ascendent.[27]

The Revolution had also failed to deliver the immediate socio-economic gains that had been promised. This made it difficult for the Girondins to draw it to a close easily in the minds of the public. While the Girondins might have been satisfied with the establishment of a republic, the sans culottess and the more radical deputies had no interest in maintaining the new status quo. The Septembriseurs (the supporters of the September Massacres such as Robespierre, Danton, Marat and their lesser allies) realized that their influence and even their safety depended on keeping the Revolution and the Revolutionary Tribunals going. Robespierre, who hated the Girondins, had proposed to include them in the proscription lists of September 1792: The Mountain, their erstwhile allies, now to a man desired their overthrow.

At the trial of Louis XVI in 1792, most Girondins voted for the "appeal to the people" not for execution, making them vulnerable to the charge of "royalism."[28] They denounced the domination by Paris and summoned provincial levies to their aid and so fell under suspicion of "federalism" as on September 25, 1792.[29] They ironically strengthened the revolutionary Commune by first decreeing its abolition but withdrawing the decree at the first sign of popular opposition. A group including some Girondins prepared a draft constitution known as the Girondin constitutional project, which was presented to the National Convention in early 1793. Thomas Paine was one of the signers of this proposal. These actions failed to understand the political climate and undermined their support.

Fall

The King was executed on January 21, 1793. Shortly thereafter the crisis came for the Girondins. In March 1793 they still had a majority in the Convention, controlled the executive council and filled the ministries. Their orators had no serious rivals in the hostile camp. However, the uncommitted delegates accounted for almost half the total number and their power began to wane. The more radical rhetoric of the Jacobins attracted the support of the revolutionary Paris Commune, the Revolutionary Sections (mass assemblies in districts) and the National Guard of Paris. The more radical revolutionaries had gained control of the Jacobin club. Brissot, absorbed in departmental work, had left to Robespierre the task of recruiting members. Robespierre used that to his advantage to fill the club with supporters. [30]

In the suspicious temper of the times, their vacillation was fatal. Marat never ceased his denunciations of the faction by which France was being betrayed to her ruin and his cry of Nous sommes trahis! ("We are betrayed!") was echoed from group to group in the streets of Paris.[31] The growing hostility of Paris to the Girondins was demonstrated by the election on February 15, 1793 of the bitter ex-Girondin Jean-Nicolas Pache as mayor. Pache had twice been minister of war in the Girondins government, but his incompetence had laid him open to strong criticism. On February 4, 1793 he had been replaced as minister of war by a vote of the Convention. This was enough to secure him the votes of the Paris electors when he was elected mayor ten days later. The Mountain was strengthened by the accession of a significant ally whose one idea was to use his new power to avenge himself on his former colleagues. Mayor Pache, with procureur of the Commune Pierre Gaspard Chaumette and deputy procureur Jacques René Hébert, controlled the armed militias of the 48 revolutionary Sections of Paris and prepared to turn this weapon against the Convention.[32]

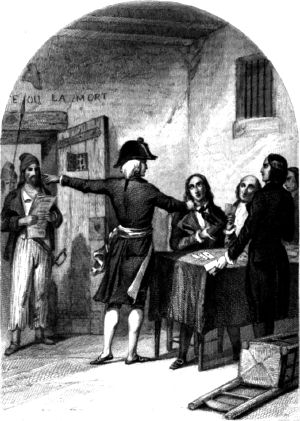

The abortive émeute (rebellion) of March 10 warned the Girondins of their danger and they responded with defensive moves, but this only further undermined their position. They unintentionally increased the prestige of their most vocal and bitter critic, Marat, by prosecuting him before the Revolutionary Tribunal, where his acquittal in April 1793 was a foregone conclusion. The Commission of Twelve was appointed on May 24, including the arrest of Varlat and Jacques Hébert and other precautionary measures. The ominous threat by Girondin leader Maximin Isnard, uttered on May 25, to "march France upon Paris" was instead met by Paris marching hastily upon the Convention. The Girondin role in the government was undermined by the popular uprisings of May 27 and May 31. Finally on June 2, 1793, François Hanriot, head of the Paris National Guards, purged the Convention of the Girondins in the Insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793.

Arrest

A list drawn up by the Commandant-General of the Parisian National Guard François Hanriot (with help from Marat) and endorsed by a decree of the intimidated Convention included 22 Girondin deputies and 10 of the 12 members of the Commission of Twelve, who were ordered to be detained at their lodgings "under the safeguard of the people." Some submitted, among them Gensonné, Guadet, Vergniaud, Pétion, Birotteau and Boyer-Fonfrède. Others, including Brissot, Louvet, Buzot, Lasource, Grangeneuve, Larivière and François Bergoeing, escaped from Paris and, joined later by Guadet, Pétion and Birotteau, set to work to organize a movement of the provinces against the capital. This attempt to stir up civil war made the wavering and frightened Convention suddenly determined. On June 13, 1793 the Convention ordered the imprisonment of the detained deputies, filling their places in the Assembly by their suppléants and initiating vigorous measures against the movement in the provinces.

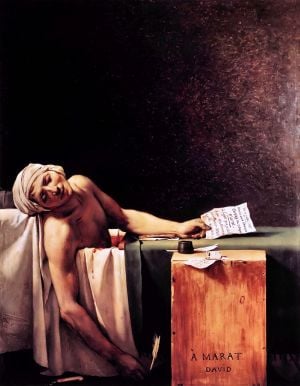

The assassination of Marat by Charlotte Corday on July 13, 1793, which she believed would rid the Girondins of their greatest nemesis, only served to increase the unpopularity of the Girondins and seal their fate.[33]The famous painting The Death of Marat depicts the fiery radical journalist and denouncer of the Girondins Jean-Paul Marat after he was stabbed to death in his bathtub by Corday. Corday did not attempt to flee and was arrested and executed.

On July 28, 1793, a decree of the Convention proscribed 21 deputies, five of whom were from the Gironde, as traitors and enemies of their country (Charles-Louis Antiboul, Boilleau the younger, Boyer-Fonfrêde, Brissot, Carra, Gaspard-Séverin Duchastel, the younger Ducos, Dufriche de Valazé, Jean Duprat, Fauchet, Gardien, Gensonné, Lacaze, Lasource, Claude Romain Lauze de Perret, Lehardi, Benoît Lesterpt-Beauvais, the elder Minvielle, the Marquis de Sillery, Vergniaud and Louis-François-Sébastien Viger). Those were sent to trial. Another 39 were included in the final acte d'accusation, accepted by the Convention on October 24, 1793, which stated the crimes for which they were to be tried as their perfidious ambition, their hatred of Paris, their "federalism" and above all their responsibility for the attempt of their escaped colleagues to provoke civil war.[34][35]

Trial and Execution

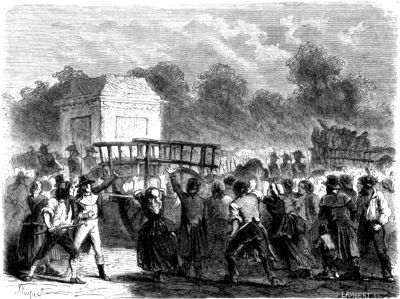

The trial of the 22 began before the Revolutionary Tribunal on October 24, 1793. The verdict was a foregone conclusion. On October 31, they were all guillotined. It took 36 minutes to decapitate all of them, including Charles Éléonor Dufriche de Valazé, who had committed suicide the previous day upon hearing the sentence he was given.[36]

Of those who escaped to the provinces, after wandering about singly or in groups most were either captured and executed or committed suicide. They included Barbaroux, Buzot, Condorcet, Grangeneuve, Guadet, Kersaint, Pétion, Rabaut de Saint-Etienne and Rebecqui.

Roland killed himself A very few escaped, including Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvrai, whose Mémoires give a detailed picture of the sufferings of the fugitives.[37]

Brissot and Madame Roland were executed and Jean Roland (who had gone into hiding) committed suicide at Rouen on November 15, 1793, a week after the execution of his wife. Paine was imprisoned, narrowly escaping execution.

Legacy

The trial and execution of the Girondins did not end revolutionary violence, but it signaled an escalation in the Reign of Terror, as first Jacques and then Danton were also purged. The rationale for the Terror that followed was the imminent peril of France, menaced on the east by the advance of the armies of the First Coalition (Austria, Prussia and Great Britain) on the west by the Royalist Revolt in the Vendée and the need for preventing at all costs the outbreak of another civil war. Another purge was in the offing, prompting a backlash against Robespierre who was himself executed on July 28, 1794, bringing the Terror to a close.[38]

Girondins as martyrs

The survivors of the party made an effort to re-enter the Convention after the fall of Robespierre on July 27, 1794, but it was not until March 5, 1795 that they were formally re-instated forming the Council of Five Hundred under the Directory.[39] On October 3 of that same year (11 Vendémiaire, year IV), a solemn fête in honor of the Girondins, "martyrs of liberty," was celebrated in the Convention.[40]

In her autobiography, Madame Roland reshapes her historical image by stressing the popular connection between sacrifice and female virtue. Her Mémoires de Madame Roland (1795) was written from prison where she was held as a Girondin sympathizer. It covers her work for the Girondins while her husband Jean-Marie Roland was Interior Minister. The book echoes such popular novels as Rousseau's Julie or the New Héloise by linking her feminine virtue and motherhood to her sacrifice in a cycle of suffering and consolation. Roland says her mother's death was the impetus for her "odyssey from virtuous daughter to revolutionary heroine" as it introduced her to death and sacrifice, including the ultimate sacrifice of her own life for her political beliefs. She helped her husband escape, but she was executed on November 8, 1793.[41]

Monument

A monument to the Girondins was erected in Bordeaux between 1893 and 1902 dedicated to the memory of the Girondin deputies who were victims of the Terror.[42] The vagueness of who actually made up the Girondins led to the monument not having any names inscribed on it until 1989. Even then, the deputies to the Convention who were memorialized were only those hailing from the Gironde department, omitting notables such as Brissot and Madame Roland.[43]

Prominent members

- Jacques Pierre Brissot (leader)

- Jean-Marie Roland

- Madame Roland

- Marquis de Condorcet

Electoral results

| Legislative Assembly | |||||

| Election year | No. of overall votes |

% of overall vote |

No. of overall seats won |

+/– | Leader |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| National Convention | |||||

| 1792 | 705,600 (3rd) | 21.4 | 160 / 749

|

||

Notes

- ↑ David Barry Gaspar and David Patrick Geggus, A Turbulent Time: The French Revolution and the Greater Caribbean (Blacks in the Diaspora) (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0253332479), 262.

- ↑ "Girondins," Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Gregory Fremont-Barnes, Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815, Volume 1 (Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007, ISBN 978-0313334450), 306.

- ↑ François Furet and Mona Ozouf, A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution, trans. Arthur Goldhammer, (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1989, ISBN 0674177282), 351.

- ↑ William Doyle, "In Search of the Girondins," New Perspectives on the French Revolution volume 4, University of Reading, 2013, 37. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 306.

- ↑ Chris Cook and John Paxton, European Political Facts 1789–1848 (London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1981, ISBN 0333216970), 10.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 306.

- ↑ John F. Bosher, The French Revolution (1988; New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1989, ISBN 039395997X), 185–191.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 307.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York, NY: Vintage, 1989, ISBN 0679726101), 719.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 403.

- ↑ J. Guadet, "Les Girondins; leur vie privée, leur vie publique, leur proscription et leur mort," Paris, FR: Perrin et Cie, 1889, 30. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Jonathan Israel, Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0691151724), 222.

- ↑ Luca Einaudi, "The Early Symbols of Political Parties During the French revolution," University of Cambridge, September 2015. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ↑ Benjamin Reilly, “Polling the Opinions: A Reexamination of Mountain, Plain, and Gironde in the National Convention,” Social Science History 28(1), 2004, 53–73.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 403.

- ↑ Israel, 222.

- ↑ Fremont-Barnes, 403.

- ↑ James Matthew Thompson, Leaders Of The French Revolution, Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell, 1932, 78. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Thomas J. Lalevée, "National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot's New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution," French History and Civilisation (Vol. 6), 2015, 66-82. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Richard Munthe Brace, "General Dumouriez and the Girondins 1792–1793," The American Historical Review 56(3), April 1951, 493–509.

- ↑ Stanley Loomis, Paris in the Terror: June 1793 - July 1794 (Philadelphia, PA and New York, NY: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1964), 186-187.

- ↑ Brace, 493-509.

- ↑ Bill Edmonds, "'Federalism' and Urban Revolt in France in 1793", Journal of Modern History, 55(1) (1983): 22-53.

- ↑ Schama, 637.

- ↑ Robert J. Alderson, This Bright Era of Happy Revolutions: French Consul Michel-Ange-Bernard Mangourit and International Republicanism in Charleston, 1792–1794 (Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina Press, 2008, ISBN 1570037450), 9.

- ↑ Schama, 651-652.

- ↑ Amédée Gabourd, Histoire de la révolution et de l'empire, volume 3 (Paris, FR: Jacques Lecoffre et Cie, 1859), 10–12. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Loomis, 186.

- ↑ Jack Fruchtman Jr., Thomas Paine: Apostle of Freedom (New York, NY: Basic Books, 1996, ISBN 1568580630), 303.

- ↑ Bette W. Oliver, Orphans on the Earth: Girondin Fugitives from the Terror, 1793-94 (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009, ISBN 978-0739127315), 55–56.

- ↑ Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013, ISBN 0199576300), 174–175.

- ↑ D.M.G. Sutherland, France 1789–1815. Revolution and Counter-Revolution (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0195205138), ch. 5.

- ↑ Schama, 793-821.

- ↑ Schama, 803–805.

- ↑ Oliver, 83–89.

- ↑ Loomis, 390-403.

- ↑ Cook and Paxton, 10.

- ↑ Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Recollections of a Provincial Past (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0195113693), 274.

- ↑ Lesley H. Walker, "Sweet and Consoling Virtue: The Memoirs of Madame Roland", Eighteenth-Century Studies 34(3), 2001, 403-419.

- ↑ "Monument élevé à la mémoire des Girondins," POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, Ministère de la Culture. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ↑ Doyle, 37-38.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alderson, Robert J. This Bright Era of Happy Revolutions: French Consul Michel-Ange-Bernard Mangourit and International Republicanism in Charleston, 1792–1794 . Columbia, SC, University of South Carolina Press, 2008. ISBN 1570037450

- Bosher, John F. The French Revolution. New York, NY: W. W. Norton, 1989. ISBN 039395997X

- Brace, Richard M. "General Dumouriez and the Girondins 1792–1793", American Historical Review 56(3) (1951): 493–509.

- Cook, Chris and John Paxton. European Political Facts 1789–1848. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 1981. ISBN 0333216970

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. Encyclopedia of the Age of Political Revolutions and New Ideologies, 1760–1815, Vol 1. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007. ISBN 978-0313334450

- Fruchtman, Jack Jr. Thomas Paine: Apostle of Freedom. New York, NY: Basic Books, 1996. ISBN 1568580630

- Furet, François and Ozouf, Mona. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0674177284

- Gaspar, David B. and David Patrick Geggus. A Turbulent Time: The French Revolution and the Greater Caribbean (Blacks in the Diaspora). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0253332479

- Israel, Jonathan. Revolutionary Ideas: An Intellectual History of the French Revolution from The Rights of Man to Robespierre. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0691151724

- Lalevée, Thomas, "National Pride and Republican grandezza: Brissot's New Language for International Politics in the French Revolution," French History and Civilisation Vol 6 (2015): 66–82. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Lamartine, Alphonse de. History of the Girondists, Vol 1: Personal Memoirs of the Patriots of the French Revolution (1847) online free in Kindle edition; Volume 1, Volume 2 | Volume 3. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- Linton, Marisa. Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 0199576300

- Loomis, Stanley. Paris in the Terror: June 1793 - July 1794. Philadelphia, PA and New York, NY: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1964.

- Oliver, Bette W. Orphans on the Earth: Girondin Fugitives from the Terror, 1793-94. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2009. ISBN 978-0739127315

- Sarmiento, Domingo F. Recollections of a Provincial Past. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195113693

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York, NY: Vintage, 1990. ISBN 0679726101

- Sutherland, D. M. G. France 1789–1815: Revolution and Counter-Revolution. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0195205138

Further reading

- de Luna, Frederick A. "The 'Girondins' Were Girondins, After All", French Historical Studies 15, 1988, 506-18.

- DiPadova, Theodore A. "The Girondins and the Question of Revolutionary Government", French Historical Studies 9(3), 1976, 432–450.

- Furet, François and Mona Ozouf. eds. La Gironde et les Girondins. Paris, FR: éditions Payot, 1991, ISBN 978-2228884006.

- Higonnet, Patrice. "The Social and Cultural Antecedents of Revolutionary Discontinuity: Montagnards and Girondins", English Historical Review, 100(396), 1985, 513–544.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., Anne Hildreth, and Alan B. Spitzer. "Was There a Girondist Faction in the National Convention, 1792–1793?" French Historical Studies 11(4), 1988, 519-36.

- Patrick, Alison. "Political Divisions in the French National Convention, 1792–93". Journal of Modern History 41(4), Dec. 1969, 422–474.

- Patrick, Alison, The Men of the First French Republic: Political Alignments in the National Convention of 1792. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2019 (original 1972), ISBN 9781421433196

- Sydenham, Michael J. "The Montagnards and Their Opponents: Some Considerations on a Recent Reassessment of the Conflicts in the French National Convention, 1792–93," Journal of Modern History 43(2), 1971, 287–293

- Whaley, Leigh Ann. Radicals: Politics and Republicanism in the French Revolution. Gloucestershire, England: Sutton Publishing, 2000, ISBN 978-0750922388

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.