Cowpox

| [[Image:{{{Image}}}|190px|center|]] | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | B08.0 |

| ICD-O: | {{{ICDO}}} |

| ICD-9 | 051.0 |

| OMIM | {{{OMIM}}} |

| MedlinePlus | {{{MedlinePlus}}} |

| eMedicine | {{{eMedicineSubj}}}/{{{eMedicineTopic}}} |

| DiseasesDB | {{{DiseasesDB}}} |

| Cowpox virus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus classification | ||||||||

|

Cowpox is a rare, mildly contagious skin disease caused by the cowpox virus, which has gained fame because of its use in the 18th century for immunization against smallpox, a deadly disease from the same family of viruses as cowpox. Cowpox received its name from milkmaids touching the udders of infected cows, however, today it is acquired most often from contact with an infected cat and is also known as catpox and the virus as catpox virus.

The virus is found in Europe, but is very rare today. Infection in humans results in localized, pustular (producing pus) lesions at the site the virus enters the skin; death is very rare (Aguayo and Calderón; Levin 2007).

Cowpox virus

The cowpox virus is a type of Orthopoxvirus, a group that includes buffalopox virus, camelpox virus, monkeypox virus, rabbitpox virus, sealpox virus, volepox virus and Ectromelia virus, which causes mousepox. The most famous member of the genus is Variola virus, which causes smallpox. Members of the Orthopoxvirus taxonomic group are members of Poxviridae (poxviruses) and the subfamily Chordopoxvirinae, members of which exclusively infect chordates.

As a member of the Orthopoxvirus taxon, cowpow is a double-stranded DNA virus that replicates in the cytoplasm of the cell (Levin 2007). The virus binds to receptors on the plasma membrane of host cells and enters the cytoplasm, where the DNA is replicated and new viral particles assembled (Levin 2007). These are released when the cell lyses and can then enter nearby cells (Levin 2007). The DNA does not integrate into the host cell and there is no latent stage (Levin 2007).

The main reservoir hosts of the cowpox virus are rodents, but it can spread to cattle, cats, humans, and zoo animals, such as elephants and large felids (Aguayo and Calderón). The main reservoir hosts are woodland rodents, particularly voles. It is from these rodents that domestic cats contract the virus. Symptoms in cats include lesions on the face, neck, forelimbs, and paws, and less commonly upper respiratory tract infection (Mansell et al. 2005).

Disease in humans

The cowpox virus is believed to be transmitted to humans by direct contact with an infected animal, with the virus entering through broken skin (Levin 2007). Although historically cowpox infection has been associated with transmission from cattle, from the infected teats of cows being milked, today it is most commonly acquired from domestic cats (Aguayo and Calderón).

Generally infection remains localized at the site of infection, with infection producing pustular lesions where the virus enters the skin (Levin 2007; Aguayo and Calderón). Common sites for the lesions are the hands, the thumbs, the first interdigital cleft, and the forefinger (Aguayo and Calderón). The vesicopustular lesions on the hands or face subsequently ulcerate and develop a black eschar before regressing spontaneously (Levin 2007; Aguayo and Calderón). However, lymphatic spread and more generalized skin infection have been reported (Levin 2007; Aguayo and Calderón). Wider spread and death are rare (Levin 2007).

Human cases today are very rare. Fewer than 150 human cases have been reported a year, with most cases having been reported in Great Britain, and smaller numbers of cases from Germany, Belgium, France, Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Russia (Levin 2007). The United States has had no reported cases of cowpox (Levin 2007).

Symptoms of infection with cowpox virus in humans are localized, pustular lesions generally found on the hands and limited to the site of introduction. The incubation period is nine to ten days. The virus is prevalent in late summer and autumn.

==

History in immunization

The cowpox virus was used to perform the first successful vaccination against another disease, smallpox, which is caused by the related Variola virus.

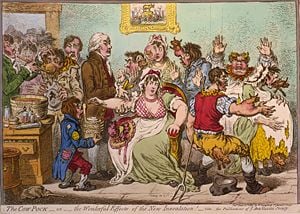

In 1796, Edward Jenner (1749-1823) inoculated against smallpox using cowpox (a mild relative of the deadly smallpox virus). While Edward Jenner has been recognized as the first doctor to give sophisticated immunization, it was British dairy farmer Benjamin Jestey who noticed that "milkmaids" did not become infected with smallpox, or displayed a milder form. Jestey took the pus from an infected cow's udder and inoculated his wife and children with cowpox, in order to artificially induce immunity to smallpox during the epidemic of 1774, thereby making them immune to smallpox. Twenty-two years later, by injecting a human with the cowpox virus (which was harmless to humans), Jenner swiftly found that the immunized human was then also immune to smallpox. The process spread quickly, and the use of cowpox immunization has led to the almost total eradication of smallpox in modern human society. After successful vaccination campaigns throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the World Health Organization (WHO) certified the eradication of smallpox in 1979.

Vaccination (Latin: vacca—cow) is so named because the first vaccine was derived from a virus affecting cows—the relatively benign cowpox virus—which provides a degree of immunity to smallpox, a contagious and deadly disease.

Therefore, the word "vaccination" — first used by Edward Jenner (an English physician) in 1796[citation needed] — has the Latin root vacca meaning cow, or from Latin root vaccinia meaning cowpox.

In the years 1770 till 1791 at least 6 people had tested independently the possibility of using the cowpox vaccine as an immunisation for smallpox in humans for the first time; among them the English farmer Benjamin Jesty, in Dorset, England in 1774 and the German teacher Peter Plett in 1791.[1] Jesty inoculated his wife and two young sons and thus spared them probable death by smallpox which was raging in the area in which they lived. His patients who had contracted and recovered from cowpox (mainly milkmaids), a disease similar to but much milder than smallpox, seemed to be immune not only to further cases of cowpox, but also to smallpox. By scratching the fluid from cowpox lesions into the skin of healthy individuals, he was able to immunize those people against smallpox. It was reported that farmers and people working regularly with cows and horses were often spared during smallpox outbreaks. More and more an investigation conducted towards 1790 by the Royal Army showed that horse-mounted troops were less infected by smallpox than infantry, and this due to a major exposure to the horse pox virus, with similar traits with cowpox's one.

However, credit was stolen by the politically astute Dr. Jenner who performed his first inoculation, twenty-two years later. It is said that Jenner made this discovery by himself without any ideas or help from others. Although Jesty was first to discover it, Jenner let everyone know and understand it, thus taking full credit for it.

Vaccination to prevent smallpox was soon practiced all over the world. During the 19th century, the cowpox virus used for smallpox vaccination was replaced by vaccinia virus. Vaccinia is in the same family as cowpox and variola but is genetically distinct from both.

Kinepox

Kinepox is an alternate term for the smallpox vaccine used in early 19th century America. Popularized by Jenner in the late 1790s, kinepox was a far safer method for inoculating people against smallpox than the previous method, variolation, which had a 3% fatality rate.

In a famous letter to Meriwether Lewis in 1803, Thomas Jefferson instructed the Lewis and Clark expedition to "carry with you some matter of the kine-pox; inform those of them with whom you may be, of its efficacy as a preservative from the smallpox; & encourage them in the use of it..."[2] Jefferson had developed an interest in protecting Native Americans from smallpox having been aware of epidemics along the Missouri River during the previous century. One year prior to his special instructions to Lewis, Jefferson had persuaded a visiting delegation of North American Indian Chieftains to be vaccinated with kinepox during the winter of 1801-2. Unfortunately, Lewis never got the opportunity to use kinepox during the pair's expedition as it had become inadvertently inactive — a common occurrence in a time before vaccines were stabilized with preservatives like glycerol or kept at refrigeration temperatures.

Historical use

Cowpox was the original vaccine of sorts for smallpox. After infection with the disease, the body (usually) gains the ability of recognizing the similar smallpox virus from its antigens and so is able to fight the smallpox disease much more efficiently. The vaccinia virus now used for smallpox vaccination is sufficiently different from the cowpox virus found in the wild as to be considered a separate virus. [3]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Plett PC (2006). [Peter Plett and other discoverers of cowpox vaccination before Edward Jenner]. Sudhoffs Arch 90 (2): 219–32.

- ↑ Jefferson's Instructions to Lewis and Clark (1803). Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ↑ Yuan, Jenifer The Small Pox Story

Jennifer Aguayo and Jessica Calderón. http://www.stanford.edu/group/virus/pox/2000/cowpox_virus.html Cowpox virus Poxviridae

Nikki A Levin Cowpox Infection, Human. eMedicine. Article Last Updated: Feb 21, 2007

Sources

- Peck, David R.. Or Perish in the Attempt: Wilderness Medicine in the Lewis & Clark Expedition. Farcountry Press. ISBN 1-56037-226-5.

| Viral diseases (A80-B34, 042-079) | |

|---|---|

| Viral infections of the central nervous system | Poliomyelitis (Post-polio syndrome) - Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis - Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy - Rabies - Encephalitis lethargica - Lymphocytic choriomeningitis - Tick-borne meningoencephalitis - Tropical spastic paraparesis |

| Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers | Dengue fever - Chikungunya - Rift Valley fever - Yellow fever - Argentine hemorrhagic fever - Bolivian hemorrhagic fever - Lassa fever - Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever - Omsk hemorrhagic fever - Kyasanur forest disease - Marburg hemorrhagic fever - Ebola |

| Viral infections characterized by skin and mucous membrane lesions | Herpes simplex - Chickenpox - Herpes zoster - Smallpox - Monkeypox - Measles - Rubella - Plantar wart - Cowpox - Vaccinia - Molluscum contagiosum - Roseola - Fifth disease - Hand, foot and mouth disease - Foot-and-mouth disease |

| Viral hepatitis | Hepatitis A - Hepatitis B - Hepatitis C - Hepatitis E |

| Viral infections of the respiratory system | Avian flu - Acute viral nasopharyngitis - Infectious mononucleosis - Influenza - Viral pneumonia |

| Other viral diseases | HIV (AIDS, AIDS dementia complex) - Cytomegalovirus - Mumps - Bornholm disease |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Mansell, Joanne K.;Rees, Christine A. (2005). "Cutaneous manifestations of viral disease", in August, John R. (ed.): Consultations in Feline Internal Medicine Vol. 5. Elsevier Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-0423-4.