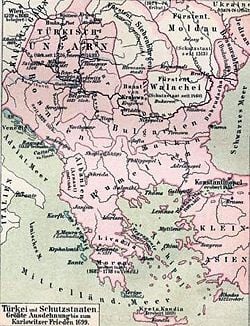

Wallachia (also spelled Walachia or "The Romanian Land") is an historical and geographical region of Romania and a former independent principality. It is situated north of the Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia is sometimes referred to as Muntenia, through identification with the larger of its two traditional sections; the smaller being Oltenia. With Moldavia and Transylvania, It is was one of three neighboring Romanian principalities. Wallachia was founded as a principality in the early fourteenth century by Basarab I, after a rebellion against Charles I of Hungary. In 1415, Wallachia accepted the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire; this lasted until the nineteenth century, albeit with brief periods of Russian occupation between 1768 and 1854. The fifteenth century ruler, Vlad III the Impaler is widely believed to have inspired the fictitious Dracula. For a few months at the start of the seventeenth century, the three principalities were united by Michael the Brave. In 1859, Wallachia united with Moldavia (the other Danubian Principality), to form the state of Romania. After World War I, Transylvania was allowed to join Romania, reunifying the three former principalities.

Like its neighbors, Wallachia was historically situated at a cross-roads of civilizations, of strategic interest to European powers and to those situated to the East, especially the Ottoman Empire. As contested territory, Wallachia's retention of a distinct sense of national identity over many years of foreign domination is testimony to the resilience and tenacity of its people. Yet animosity has not always characterized Wallachia's relations with those who might be described as the religious and cultural Other. Wallachia in the seventeenth century saw a lengthy period of peace and stability. Regardless of the battles fought and changes in power and in political authority at the elite level, many people in the region discovered that they could value different aspects of the cultural traditions that impacted their lives through trade, the acquisition of education or by exposure to another religious tradition. History warns humanity as a race that civilizational clash is one possibility when civilizations confront each other as their borders. However, when the full story of what life was like in such frontier-zones as Wallachia is told, fruitful exchange between cultures will also be part of the narrative.

Name

The name Wallachia, generally not used by Romanians themselves (but present in some contexts as Valahia or Vlahia), is derived from the ValachsÔÇöa word of German origin also present as the Slavic VlachsÔÇöused by foreigners in reference to Romanians.

In the early Middle Ages, in Slavonic texts, the name of Zemli Ungro-Vlahiskoi ("Hungaro-Wallachian Land") was also used. The term, translated in Romanian as Ungrovalahia, remained in use up to the modern era in a religious context, referring to the Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan seat of Hungaro-Wallachia. Official designations of the state were Muntenia and Ţeara Rumânească.

For long periods before the fourteenth century, Wallachia was referred to as Vla┼íko by Bulgarian sources (and Vla┼íka by Serbian sources), Walachei or Walachey by German (Transylvanian Saxon) sources. The traditional Hungarian name for Wallachia is Havasalf├Âld, or literally "Snowy Lowlands" (the older form is Havaselve, which means "Land beyond the snowy mountains"). In Ottoman Turkish and Turkish, Eflak, a word derived from "Vlach," is used.

Geography

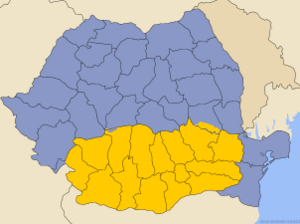

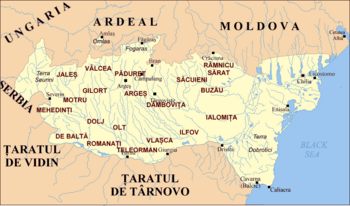

Wallachia is situated north of the Danube (and of present-day Serbia and Bulgaria) and south of the Southern Carpathians, and is traditionally divided between Muntenia in the east (as the political center, Muntenia is often understood as being synonymous with Wallachia), and Oltenia (a former banat) in the west. (A Banate was a tributary state, usually of Hungary.) The division line between the two is the Olt River.

Wallachia's traditional border with Moldavia coincided with the Milcov River for most of its length. To the east, over the Danube north-south bend, Wallachia neighbors Dobruja). Over the Carpathians, Wallachia shared a border with Transylvania. Wallachian princes have for long held possession of areas north of this line (Amla┼č, Ciceu, F─âg─âra┼č, and Ha┼úeg), which are generally not considered part of Wallachia-proper.

The capital city changed over time, from C├ómpulung to Curtea de Arge┼č, then to T├órgovi┼čte and, after the late 1500s, to Bucharest.

History

From Roman rule to the state's establishment

In the Second Dacian War (105 C.E.) western Oltenia became part of the Roman province of Dacia, with parts of Wallachia included in the Moesia Inferior province. The Roman limes was initially built along the Olt River (119), before being moved slightly to the east in the second centuryÔÇöduring which time it stretched from the Danube up to Ruc─âr in the Carpathians. The Roman line fell back to the Olt in 245, and, in 271, the Romans pulled out of the region.

The area was subject to Romanization sometime during the Migration Period, when most of present-day Romania was also subject to the presence of Goths and Sarmatian peoples known as the Mure┼č-Cerneahov culture, followed by waves of other nomadic peoples. In 328, the Romans built a bridge between Sucidava (Celei) and Oescus (near Gigen) which indicates that there was a significant trade with the peoples north of the Danube (a short period of Roman rule in the area is attested under Constantine I). The Goths attacked the Roman Empire south of the Danube in 332, settling north of the Danube, then later to the south. The period of Goth rule ended when the Huns arrived in the Pannonian Plain, and, under Attila the Hun, attacked and destroyed some 170 settlements on both sides of the Danube.

Byzantine influence is evident during the fifth to sixth century, such as the site at Ipote┼čti-C├ónde┼čti, but from the second half of the sixth century and in the seventh century, Slavic peoples crossed the territory of Wallachia and settled in it, on their way to Byzantium, occupying the southern bank of the Danube. In 593, the Byzantine commander-in-chief Priscus defeated Slavs, Avars, and Gepids on future Wallachian territory, and, in 602, Slavs suffered a crucial defeat in the area; [|Flavius Mauricius Tiberius]], who ordered his army to be deployed north of the Danube, encountered his troops' strong opposition.

Wallachia was under the control of the First Bulgarian Empire from its establishment in 681, until approximately the Magyar conquest of Transylvania at the end of the tenth century. With the decline and subsequent fall of the Bulgarian state to Byzantium (in the second half of the tenth century up to 1018), Wallachia came under the control of the Pechenegs (a Turkic people) who extended their rule west through the tenth and eleventh century, until defeated around 1091, when the Cumans of southern Russia took control of the lands of Moldavia and Wallachia. Beginning with the tenth century, Byzantine, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and later Western sources mention the existence of small polities, possibly peopled by, among others, Vlachs/Romanians led by knyazes (princes) and voivodes (military commanders)ÔÇöat first in Transylvania, then in the twelfth-thirteenth centuries in the territories east and south of the Carpathians.

In 1241, during the Mongol invasion of Europe, Cuman domination was endedÔÇöa direct Mongol rule over Wallachia was not attested, but it remains probable. Part of Wallachia was probably briefly disputed by the Hungarian Kingdom and Bulgarians in the following period, but it appears that the severe weakening of Hungarian authority during the Mongol attacks contributed to the establishment of the new and stronger polities attested in Wallachia for the following decades.

Creation

One of the first written pieces of evidence of local voivodes (commanders) is in connection with Litovoi (1272), who ruled over land each side of the Carpathians (including F─âg─âra┼č in Transylvania), and refused to pay tribute to the Hungarian King Ladislaus IV. His successor was his brother B─ârbat (1285-1288). The continuing weakening of the Hungarian state by further Mongol invasions (1285-1319) and the fall of the ├ürp├íd dynasty opened the way for the unification of Wallachian polities, and to independence from Hungarian rule.

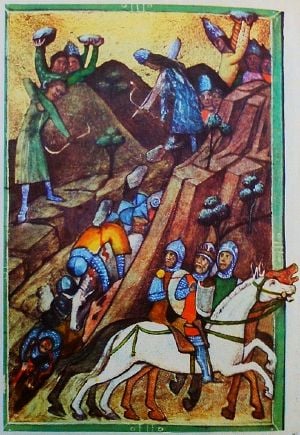

Wallachia's creation, held by local traditions to have been the work of one Radu Negru, is historically connected with Basarab I (1310-1352), who rebelled against Charles I of Hungary and took up rule on either side of the Olt River, establishing his residence in C├ómpulung as the first ruler in the House of Basarab. Basarab refused to grant Hungary the lands of F─âg─âra┼č, Amla┼č and the Banat of Severin, defeated Charles in the Battle of Posada (1330), and extended his lands to the east, to comprise lands as far as Kilia (in the Bujak, as the origin of Bessarabia); rule over the latter was not preserved by following princes, as Kilia fell to the Nogais c. 1334.

Basarab was succeeded by Nicolae Alexandru, followed by Vladislav I. Vladislav attacked Transylvania after Louis I occupied lands south of the Danube, conceded to recognize him as overlord in 1368, but rebelled again in the same year; his rule also witnessed the first confrontation between Wallachia and the Ottoman Turks (a battle in which Vladislav was allied with Ivan Shishman of Bulgaria). Under Radu I and his successor Dan I, the realms in Transylvania and Severin continued to be disputed with Hungary.

1400-1600

Mircea the Elder to Radu the Great

As the entire Balkan Peninsula become an integral part of the emerging Ottoman Empire (a process which concluded with the Fall of Constantinople to Sultan Mehmed II in 1453), Wallachia became engaged in frequent confrontations and, in the final years of Mircea the Elder's reign, became an Ottoman tributary state. Mircea (reigned 1386-1418), initially defeated the Ottomans in several battles (including that of Rovine in 1394), driving them away from Dobruja and briefly extending his rule to the Danube Delta, Dobruja and Silistra (ca.1400-1404). He oscillated between alliances with Sigismund of Hungary and Poland (taking part in the Battle of Nicopolis), and accepted Ottoman a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1415, after Mehmed I took control of Turnu and GiurgiuÔÇöthe two ports remained part of the Ottoman state, with brief interruptions, until 1829. In 1418-1420, Mihail I defeated the Ottomans in Severin, only to be killed in battle by the counter-offensive; in 1422, the danger was averted for a short while when Dan II inflicted a defeat on Murad II with the help of Pippo Spano.

The peace signed in 1428 inaugurated a period of internal crisis, as Dan had to defend himself against Radu Prasnaglava, who led the first in a series of boyar (noblemen) coalitions against established princes (in time, these became overtly pro-Ottoman in answer to repression). Victorious in 1431 (the year when the boyar-backed Alexandru I Aldea took the throne), boyars (nobles) were dealt successive blows by Vlad II Dracul (1436-1442; 1443-1447), who nevertheless attempted to compromise between the Sultan and the Holy Roman Empire.

The following decade was marked by the conflict between the rival houses of D─âne┼čti and Dr─âcule┼čti, the influence of John Hunyadi, Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary, and, after the neutral reign of Vladislav II, by the rise of the notorious Vlad III the Impaler, widely believed to be the inspiration behind Bram Stoker's Dracula. Vlad, during whose rule Bucharest was first mentioned as a princely residence, exercised terror on rebellious boyars, cut off all links with the Ottomans, and, in 1462, defeated Mehmed II's offensive during The Night Attack before being forced to retreat to T├órgovi┼čte and accepting to pay an increased tribute. His parallel conflicts with the pretenders Radu cel Frumos and Laiot─â Basarab brought occupations of Wallachia by the troops of Matthias Corvinus of Hungary and the Moldavian prince Stephen III (1473; 1476-1477). Radu the Great (1495-1508) reached several compromises with the boyars, ensuring a period of internal stability that contrasted his clash with Bogdan the Blind of Moldavia.

Mihnea cel R─âu to Petru Cercel

The late 1400s saw the ascension of the powerful Craiove┼čti family, virtually independent rulers of the Oltenian banat, who sought Ottoman support in their rivalry with Mihnea cel R─âu (1508-1510) and replaced him with Vl─âdu┼ú; after the latter proved to be hostile to the bans, the House of Basarab formally ended with the rise of Neagoe Basarab, a Craiove┼čti. Neagoe's peaceful rule (1512-1521), noted for its cultural aspects (the building of the Curtea de Arge┼č Cathedral and Renaissance influences), also saw an increase in influence for the Saxon merchants in Bra┼čov and Sibiu, and Wallachia's alliance with Louis II of Hungary. Under Teodosie, the country was again under a four-month-long Ottoman occupation, a military administration which seemed to be an attempt to create a Wallachian Pashaluk. (In the Ottoman empire, a Pahsaluk was an eyelet or province under a governor appointed by the Sultan who carried the rank of Pasha.) This danger rallied all boyars in support of Radu de la Afuma┼úi (four rules between 1522 and 1529), who lost the battle after an agreement between the Craiove┼čti and Sultan S├╝leyman the Magnificent; Prince Radu eventually confirmed S├╝leyman's position as suzerain, and agreed to pay an even higher tribute.

Ottoman suzerainty remained virtually unchallenged throughout the following 90 years. Radu Paisie, who was deposed by S├╝leyman in 1545, ceded the port of Br─âila to Ottoman administration in the same year; his successor Mircea Ciobanul (1545-1554; 1558-1559), a prince without any claim to noble heritage, was imposed on the throne and consequently agreed to a decrease in autonomy (increasing taxes and carrying out an armed intervention in TransylvaniaÔÇösupporting the pro-Turkish John Z├ípolya). Conflicts between boyar families became stringent after the rule of P─âtra┼čcu cel Bun, and boyar ascendancy over rulers was obvious under Petru the Younger (1559-1568) whose was and marked by huge increases in taxes.

The Ottoman Empire increasingly relied on Wallachia and Moldavia for the supply and maintenance of its |military forces; the local army, however, soon disappeared due to the increased costs and the much more obvious efficiency of mercenary troops.

1600s

Initially profiting from Ottoman support, Michael the Brave ascended to the throne in 1593, and attacked the troops of Murad III north and south of the Danube in an alliance with Transylvania's Sigismund Báthory and Moldavia's Aron Vodă. He soon placed himself under the suzerainty of Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor, and, in 1599-1600, intervened in Transylvania against Poland's king Sigismund III Vasa, placing the region under his authority; his brief rule also extended to Moldavia later in the following year. Following Michael's downfall, Wallachia was occupied by the Polish-Moldavian army of Simion Movilă, who held the region until 1602, and was subject to Nogai attacks in the same year.

The last stage in the growth of the Ottoman Empire brought increased pressures on Wallachia: political control was accompanied by Ottoman economical hegemony, the discarding of the capital in T├órgovi┼čte in favor of Bucharest (closer to the Ottoman border, and a rapidly-growing trade center), the establishment of serfdom under Michael the Brave as a measure to increase manorial revenues, and the decrease in importance of low-ranking boyars. (Threatened with extinction, they took part in the seimeni rebellion of 1655. (The Seimeni were mercenaries charged with protecting the Prince, whose land grants were being curtailed. They rebelled in 1655 but were defeated.) Furthermore, the growing importance of appointment to high office in front of land ownership brought about an influx of Greek and Levantine families, a process already resented by locals during the rules of Radu Mihnea in the early 1600s. Matei Basarab, a boyar appointee, brought a long period of relative peace (1632-1654), with the noted exception of the 1653 Battle of Finta, fought between Wallachians and the troops of Moldavian prince Vasile Lupu ÔÇö ending in disaster for the latter, who was replaced with Prince Matei's favorite, Gheorghe ┼×tefan, on the throne in Ia┼či. A close alliance between Gheorghe ┼×tefan and Matei's successor Constantin ┼×erban was maintained by Transylvania's George II R├ík├│czi, but their designs for independence from Ottoman rule were crushed by the troops of Mehmed IV in 1658-1659. The reigns of Gheorghe Ghica and Grigore I Ghica, the sultan's favorites, signified attempts to prevent such incidents; however, they were also the onset of a violent clash between the B─âleanu and Cantacuzino boyar families, which was to mark Wallachia's history until the 1680s. The Cantacuzinos, threatened by the alliance between the B─âleanus and the |Ghicas, backed their own choice of princes (Antonie Vod─â din Pope┼čti and George Ducas) before promoting themselvesÔÇöwith the ascension of ┼×erban Cantacuzino (1678-1688).

Russo-Turkish Wars and the Phanariotes

Wallachia became a target for Habsburg incursions during the last stages of the Great Turkish War c. 1690, when the ruler Constantin Br├óncoveanu secretly and unsuccessfully negotiated an anti-Ottoman coalition. Br├óncoveanu's reign (1688-1714), noted for its late Renaissance cultural achievements, also coincided with the rise of Imperial Russia under |Emperor Peter the GreatÔÇöhe was approached by the latter during the Russo-Turkish War of 1710-1711, and lost his throne and life sometime after sultan Ahmed III caught news of the negotiations. Despite his denunciation of Br├óncoveanu's policies, ┼×tefan Cantacuzino attached himself to Habsburg projects and opened the country to the armies of Prince Eugene of Savoy; he was himself deposed and executed in 1716.

Immediately following the deposition of Prince ┼×tefan, the Ottomans renounced the purely nominal elective system (which had by then already witnessed the decrease in importance of the Boyar Divan (council) over the sultan's decision), and princes of the two Danubian Principalities were appointed from the Phanariotes of Istanbul. (Wealthy Greek merchants.) Inaugurated by Nicholas Mavrocordatos in Moldavia after Dimitrie Cantemir, Phanariote rule was brought to Wallachia in 1715 by the very same ruler. The tense relations between boyars and princes brought a decrease in the number of taxed people (as a privilege gained by the former), a subsequent increase in total taxes, and the enlarged powers of a boyar circle in the Divan.

In parallel, Wallachia became the battleground in a succession of wars between the Ottomans on one side and Russia or the Habsburg Monarchy on the other. Mavrocordatos himself was deposed by a boyar rebellion, and arrested by Habsburg troops during the Austro-Turkish War of 1716-18, as the Ottomans had to concede Oltenia to Charles VI of Austria (the Treaty of Passarowitz). The region, subject to an enlightened absolutist rule that soon disenchanted local boyars, was returned to Wallachia in 1739 (the Treaty of Belgrade, upon the close of the Austro-Turkish War of 1737-39). Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos, who oversaw the new change in borders, was also responsible for the effective abolition of serfdom in 1746 (which put a stop to the exodus of peasants into Transylvania); during this period, the ban of Oltenia moved his residence from Craiova to Bucharest, signaling, alongside Mavrocordatos' order to merge his personal treasury with that of the country, a move towards centralized government.

In 1768, during the Fifth Russo-Turkish War, Wallachia was placed under its first Russian occupation (helped along by the rebellion of P├órvu Cantacuzino). The Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca (1774) allowed Russia to intervene in favor of Eastern Orthodox Ottoman subjects, curtailing Ottoman pressuresÔÇöincluding the decrease in sums owed as tributeÔÇöand, in time, relatively increasing internal stability while opening Wallachia to more Russian interventions.

Habsburg troops, under Prince Josias of Coburg, again entered the country during the Russo-Turkish-Austrian War, deposing Nicholas Mavrogenis in 1789. A period of crisis followed the Ottoman recovery: Oltenia was devastated by the expeditions of Osman Pazvanto─člu, a powerful rebellious pasha (A non-hereditary title awarded to senior governors) whose raids even caused prince Constantine Hangerli to lose his life on suspicion of treason (1799), and Alexander Mourousis to renounce his throne (1801). In 1806, the Russo-Turkish War of 1806-1812 was partly instigated by the Porte's deposition of Constantine Ypsilantis in BucharestÔÇöin tune with the Napoleonic Wars, it was instigated by the French Empire, and also showed the impact of the Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca (with its permissive attitude towards Russian political influence in the Danubian Principalities); the war brought the invasion of Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich.

After the Peace of Bucharest (1812), the rule of Jean Georges Caradja, although remembered for a major plague epidemic, was notable for its cultural and industrial ventures. During the period, Wallachia increased its strategic importance for most European states interested in supervising Russian expansion; consulates were opened in Bucharest, having an indirect but major impact on Wallachian economy through the protection they extended to sudiţi (fabric) traders (who soon competed successfully against local guilds).

From Wallachia to Romania

Early 1800s

The death of prince Alexander Soutzos in 1821, coinciding with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, established a boyar regency which attempted to block the arrival of Scarlat Callimachi to his throne in Bucharest. The parallel uprising in Oltenia, carried out by the Pandur leader Tudor Vladimirescu, although aimed at overthrowing the ascendancy of Greeks, compromised with the Greek revolutionaries in the Filiki Eteria and allied itself with the regents, while seeking Russian support.

On March 21, 1821, Vladimirescu entered Bucharest. For the following weeks, relations between him and his allies worsened, especially after he sought an agreement with the Ottomans; Eteria's leader Alexander Ypsilantis, who had established himself in Moldavia and, after May, in northern Wallachia, viewed the alliance as brokenÔÇöhe had Vladimirescu executed, and faced the Ottoman intervention without Pandur or Russian backing, suffering major defeats in Bucharest and Dr─âg─â┼čani (before retreating Austrian custody in Transylvania). These violent events, which had seen the majority of Phanariotes siding with Ypsilantis, made Sultan Mahmud II place the Principalities under its occupation (evicted by a request of several European powers), and sanction the end of Phanariote rules: in Wallachia, the first prince to be considered a local one after 1715 was Grigore IV Ghica. Although the new system was confirmed for the rest of Wallachia's existence as a state, Ghica's rule was abruptly ended by the devastating Russo-Turkish War of 1828-1829.

The 1829 Treaty of Adrianople, without overturning Ottoman suzerainty, placed Wallachia and Moldavia under Russian military rule, awarding them the first common institutions and the semblance of a constitution. Wallachia was returned ownership of Br─âila, Giurgiu (both of which soon developed into major trading cities on the Danube), and Turnu M─âgurele. The treaty also allowed Moldavia and Wallachia to freely trade with countries other than the Ottoman Empire, which signaled substantial economic and urban growth, as well as improving the peasant situation. Princes were now elected for life ÔÇťrather than for short periods ÔÇŽfrom among the boyars.ÔÇŁ[2] Many of the provisions had been specified by the 1826 Akkerman Convention between Russia and the Ottomans (it had never been fully implemented in the three-year interval). The duty of overseeing of the Principalities was left to Russian general Pavel Kiselyov; this interval was marked by a series of major changes, including the reestablishment of a Wallachian Army (1831), a tax reform (which nonetheless confirmed tax exemptions for the privileged), as well as major urban works in Bucharest and other cities. In 1834, Wallachia's throne was occupied by Alexandru II GhicaÔÇöa move in contradiction with the Adrianople treaty, as he had not been elected by the new Legislative Assembly; removed by the suzerains in 1842, he was replaced with an elected prince, Gheorghe Bibescu.

1840s-1850s

Opposition to Ghica's arbitrary and highly conservative rule, together with the rise of liberal and radical currents, was first felt with the protests voiced by Ion Câmpineanu (quickly repressed); subsequently, it became increasingly conspiratorial, and centered on those secret societies created by young officers such as Nicolae Bălcescu and Mitică Filipescu.

Fr─â┼úia, a clandestine movement created in 1843, began planning a revolution to overthrow Bibescu and repeal Regulamentul Organic in 1848 (inspired by the European rebellions of the same year, by new notions of state-hood and nationalism). Their pan-Wallachian coup d'├ętat was initially successful only near Turnu M─âgurele, where crowds cheered the Islaz Proclamation (June 21); among others, the document called for political freedoms, independence, land reform, and the creation of a national guard. On June 11-12, the movement was successful in deposing Bibescu and establishing a Provisional Government. Although sympathetic to the anti-Russian goals of the revolution, the Ottomans were pressured by Russia into repressing it: Ottoman troops entered Bucharest on September 13. Russian and Turkish troops, present until 1851, brought Barbu Dimitrie ┼×tirbei to the throne, during which interval most participants in the revolution were sent into exile.

Briefly under renewed Russian occupation during the Crimean War, Wallachia and Moldavia were given a new status with a neutral Austrian administration (1854-1856) and the Treaty of Paris (1856): A tutelage shared by Ottomans and a Congress of Great Powers (the Great Britain, the Second French Empire, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the Austrian Empire, Prussia, and, albeit never again fully, Russia), with a kaymakam'ÔÇÖ (governor) led internal administration. An emerging movement for union of the two Danubian Principalities was advocated by the French and by their Sardinian allies, supported by Russia and Prussia but was rejectedÔÇöor regarded with suspicionÔÇöby all other overseers. The prince of Wallachia supported union, ÔÇťsince it would give his province supremacy because of its size, while the Prince of Moldavia opposed it from the same consideration.ÔÇŁ The plan, as it originally developed, left the two principalities separate but with a joint commission ÔÇťto draw up common law codes and other legislation needed by both.ÔÇŁ[3]

After an intense campaign, a formal union was ultimately granted: nevertheless, elections for the ad-hoc divans (councils) of 1859 profited from a legal ambiguity (the text of the final agreement specified two thrones, but did not prevent any single person from simultaneously taking part in and winning elections in both Bucharest and Ia┼či). Alexander John Cuza, who ran for the unionist Partida Na┼úional─â, won the elections in Moldavia on January 5; Wallachia, which was expected by the unionists to carry the same vote, returned a majority of anti-unionists to its divan.

Those elected changed their allegiance after a mass protest of Bucharest crowds, and Cuza was voted prince of Wallachia on February 5 (January 24 Old Style and New Style dates), consequently confirmed as Domnitor of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia (of Romania from 1861). Internationally recognized only for the duration of his reign, the union was irreversible after the ascension of Carol I in 1866 (coinciding with the Austro-Prussian War, it came at a time when Austria, the main opponent of the decision, was not in a position to intervene). Romania proclaimed its independence in 1877 and in 1881, became a Kingdom.

Legacy

Situated at a cultural and civilizational crossroads, Wallachian culture, like that of the rest of Romania, is a blend of different influences, including Slav, Saxon, Ukrainian, Roman, Gypsy and Turkish. While hostility towards the powers and cultures that conquered the region over the years fed a strong desire for self-determination, animosity did not always characterize relationships. In many respects, Wallachia also bridged-cultures and created a space where exchange took place between different peoples. Conflict was often at the level of the princes and leaders, while life at the local level went on regardless of who was winning or losing on the battlefield. At the local level, people valued what they saw as useful or as beautiful in the different cultures that impacted their lives. Thus,

Romania has its unique culture, which is the product of its geography and of its distinct historical evolution. Romanians are the sole Christian Orthodox among the Latin peoples and the sole Latin people in the Eastern Orthodox area. The Romanians sense of identity has always been deeply related to their Roman roots, in conjunction with their Orthodoxy. A sense of their ethnic insularity in the area has kept Romanians available for a fruitful communication with other peoples and cultures.[4]

When the story of inter-civilizations relations is told, periods of fruitful exchange and even of peaceful coexistence (not infrequently under some form of imperial rule, must not be neglected. The people of Wallachia maintained their sense of identity through centuries of political domination by others. They are no less proud of their culture than if it had developed in isolation, regarding it as a unique product of their geo-political circumstances.

Notes

- ÔćĹ Petre Dan, Hotarele rom├ónismului ├«n date (Bucharest, HU: Editura, Litera International, 2005, ISBN 973675278X), 32-34.

- ÔćĹ Shaw and Shaw (1977), 135.

- ÔćĹ Shaw and Shaw (1977), 142.

- ÔćĹ Romana Folklore Festival, Romania: Culture. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- East, W. Gordon. 1973. The Union of Moldavia and Wallachia, 1859; an Episode in Diplomatic History. New York, NY: Octagon Books. ISBN 9780374924508.

- Florescu, Radu, and Raymond T. McNally. 1974. Dracula: A Biography of Vlad the Impaler, 1431-1476. London, UK: Hale. ISBN 9780709146148.

- Hentea, C─âlin. 2007. Brief Romanian Military History. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810858206.

- Panaite, Viorel. 2000. The Ottoman Law of War and Peace: The Ottoman Empire and Tribute Payers. East European monographs, no. 562. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs. ISBN 9780880334617.

- Shaw, Stanford J and Shaw, Ezel Kural. 1977. History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291668.

- Stoker, Bram. 1897. 2008. Dracula. Richmond, VA: Oneoworld Classics. ISBN 9781847490261.

- Wilkinson, William. 1971. An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. New York, NY: Arno Press. ISBN 9780405027796.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclop├Ždia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.