Michael the Brave

Michael the Brave (1558-1601) was the Prince of Wallachia (1593-1601), of Transylvania (1599-1600), and of Moldavia (1600) three principalities that he united under his rule. He was born under the family name of Pătraşcu. During his reign, which coincided with the Long War, these three principalities forming the territory of present-day Romania and Moldova were united for the first time under a single Romanian ruler, though the unification lasted for less than six months. He is regarded as one of Romania's greatest national heroes. His reign began in late 1593, two years before the war with the Ottomans started, a conflict in which the Prince fought the Battle of Călugăreni, considered the most important battle of his reign. Although the Wallachians emerged victorious from the battle, Michael was forced to retreat with his troops and wait for aid from his allies. The war continued until a peace finally emerged in January 1597, but this only lasted for a year and a half. Peace was again reached in late 1599, when Michael was unable to continue the war due to lack of support from his allies.

In 1600, Michael won the Battle of Şelimbăr and soon entered Alba Iulia, becoming the Prince of Transylvania. A few months later, Michael's troops invaded Moldavia and reached its capital, Suceava. The Moldavian leader Ieremia Movilă fled to Poland and Michael was declared Prince of Moldavia. Due to inadequate support from his allies, Michael could not keep the control of all three provinces and the nobles of Transylvania rose against him along with, to a lesser extent, the boyars(Nobles, or aristocrats) in Moldavia and Wallachia. Michael, allied with the Austrian General Giorgio Basta, defeated an uprising by the Hungarian nobility at Gurăslău. Immediately after this, Basta ordered the assassination of Michael, which took place on August 9, 1601. It would be another 250 years before Romania would again be united.[1] Wallachia and Moldavia fell to Ottoman rule while Transylvania became part of Austria-Hungary. In the nineteenth century, Michael's name was invoked to encourage a new awakening of national consciousness. Michael succeeded, briefly, in freeing the Romanian space from external domination, an achievement that properly served to inspire aspirations for freedom in a later era.

Early life

Very little is known about Michael's childhood and early years as an adult. He claimed to have been the illegitimate son of Wallachian Prince Pătraşcu cel Bun, but may invented his descent in order to justify his rule. His mother was named Teodora, of Oraşul de Floci, and was a member of the Cantacuzino family. (The Cantazino family claim descent from the Byzantine Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos and were Romanian boyars.)

Michael's political career was quite spectacular, as he became the Ban (Bans were usually subject to the over-lordship of another ruler. It can be translated as viceroy, although many Bans were more or less autonomous princes) of Mehedinţi in 1588, stolnic (a court official) at the court of Prince Mihnea Turcitul by the end of 1588, and Ban of Craiova in 1593—during the rule of Alexandru cel Rău. The latter had him swear before 12 boyars (nobles) that he was not of princely descent (according to the eighteenth century chronicle of Radu Popescu). Still, in May 1593, conflict did break out between Alexandru and the Ban and Michael was forced to flee to Transylvania. He was accompanied by his half-brother Radu Florescu, Radu Buzescu and several other supporters. After spending two weeks at the court of Sigismund Báthory he left for Constantinople, where with help from his cousin Andronic Cantacuzino and Patriarch Jeremiah II he negotiated Ottoman support for his accession to the Wallachian throne. He was invested Prince by the Sultan in September 1593, and started his effective rule on October 11.[2]

Wallachia

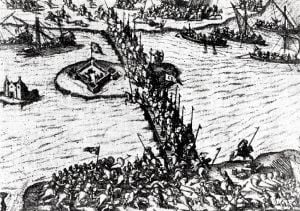

Not long after he became Prince of Wallachia, Michael began to fight his Ottoman overlord in a bid for independence. The next year he joined the Christian alliance of European powers formed by Pope Clement VIII, against the Turks, and signed treaties with Sigismund Báthory of Transylvania, Aron Vodă of Moldavia, and the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II. He started a campaign against the Turks in the autumn of 1594, conquering several citadels near the Danube, including Giurgiu, Brăila, Hârşova, and Silistra, while his Moldavian allies defeated the Turks in Iaşi and other parts of Moldova.[3] Mihai continued his attacks deep within the Ottoman Empire, taking the forts of Nicopolis, Ribnic, and Chilia and even reaching as far as Adrianople. At one point his forces were only 24 kilometers from Constantinople.

In 1595, Sigismund Báthory staged an elaborate plot and had Aron of Moldavia removed from power. Ştefan Răzvan arrested Aron on alleged treason charges on the night of April 24, and sent him to Alba Iulia with his family and treasure. Aron would die by the end of May, after being poisoned in the castle of Vint. Báthory was forced to justify his actions before the European powers, since Aron had actively joined the anti-Ottoman coalition. Báthory replaced Aron with hatman Ştefan Răzvan, and Sigismund himself gave the latter both the investment act and the insignia of power, thus acting in overlord of Moldavia. On May 24 1595 at Alba Iulia, Ştefan Răzvan signed a binding treaty, formally placing Moldavia under Transylvanian sovereignty.[4] Only a month later in the same city of Alba Iulia, Wallachian boyars signed a similar treaty on Michael's behalf. Thus, by July 1595, Sigismund Báthory was de facto Prince of all the three countries: Transylvania, Wallachia and Moldavia.[5] From the point of view of Wallachian internal politics, the Treaty of Alba Iulia officialized what could be called a boyar regime, reinforcing the already important political power of the noble elite. According to the treaty, a council of 12 great boyars was to take part alongside the voivode in the executive rule of the country.

Boyars could no longer be executed without the knowledge and approval of the Transylvanian Prince and if convicted for treason their fortunes could no longer be confiscated. Apparently Michael was displeased with the final form of the treaty negotiated by his envoys but had to comply. He would try to avoid the obligations imposed on him for the rest of his reign.

During his reign, Michael relied heavily on the loyalty and support of a group of west-Wallachian lords of which the Buzescus were probably the most important, and on his own relatives on his mother's side, the Cantacuzinos. He consequently protected their interests throughout his reign; for example, he passed a law binding serfs to lands owned by aristocrats. From the standpoint of religious jurisdiction, the Treaty of Alba Iulia had another important consequence, as it placed all the Eastern Orthodox bishops in Transylvania under the jurisdiction of the Metropolitan Seat of Târgovişte.[4]

During this period the Ottoman army, based in Ruse, was preparing to cross the Danube and undertake a major attack. Michael was quickly forced to retreat and the Turk forces started to cross the Danube on August 4, 1595. As his army was overwhelmed by numbers, Michael was unable to carry a battle in open field, and he decided to fight in a swamp located near the village of Călugăreni, on the Neajlov river. The Battle of Călugăreni started on August 13, and Michael defeated the Ottoman army led by Sinan Pasha. Despite the victory, he retreated to his winter camp in Stoeneşti because he had too few troops to mount a full scale attack against the remaining Ottoman forces. He subsequently joined forces with Sigismund Báthory's 40,000-man army (led by István Bocskay) and counterattacked the Ottomans, freeing the towns of Târgovişte (October 8), Bucharest (October 12) and Brăila, temporarily removing Wallachia from Ottoman rule.

The fight against the Ottomans continued in 1596, when Michael made several incursions south of the Danube at Vidin, Pleven, Nicopolis, and Babadag, where he was assisted by the local Bulgarians during the First Tarnovo Uprising.[6]

During late 1596, Michael was faced with an unexpected attack from the Tatars, who had destroyed the towns of Bucharest and Buzău. By the time Michael gathered his army and to counterattack, the Tatars had speedily retreated and so no battle was fought. Michael was determined to continue the battle against the pagans, but he was prevented because he lacked support from Sigismund Báthory and Rudolf II. On January 7, 1597, Hasan Pasha declared the independence of Wallachia under Michael's rule,[7] but Michael knew that this was only an attempt to divert him from preparing for another future Ottoman attack. Michael again requested Rudolf II's support and Rudolf finally agreed to send financial assistance to the Wallachian ruler. On June 9 1598, a formal treaty was reached between Michael and Rudolf II. According to the treaty, the Austrian ruler would give Wallachia sufficient money to maintain a 5,000-man army, as well as armaments and supplies.[8] Shortly after the treaty was signed, the war with the Ottomans resumed and Michael besieged Nicopolis on September 10 1598 and took control of Vidin. The war with the Ottomans continued until June 26 1599, when Michael, lacking the resources and support to continue prosecuting the war, was again forced to sign a peace treaty.

Transylvania

In April 1598, Sigismund resigned as Prince of Transylvania in favor of the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II (who was also the King of Hungary), reversed his decision in October 1598, and then resigned again in favor of Cardinal Andrew Báthory, his cousin.[9] Báthory was close to the Polish chancellor and hetman Jan Zamoyski and placed Transylvania under the influence of the King of Poland, Sigismund III Vasa. He was also a trusted ally of the new Moldavian Prince Ieremia Movilă, one of Michael's greatest enemies.[10] Movilă had deposed Ştefan Rǎzvan with the help of Polish hetman Jan Zamoyski in August 1595.[10]

Having to face this new threat, Michael asked Emperor Rudolf to become the sovereign of Wallachia. Báthory issued an ultimatum demanding that Michael abandon his throne.[11] Michael decided to attack Báthory immediately to prevent invasion. He would later describe the events: "I rose with my country, my children, taking my wife and everything I had and with my army [marched into Transylvania] so that the foe should not crush me here." He left Târgovişte on October 2 and by October 9 ,he reached Prejmer in Southern Transylvania, where he met envoys from the city of Braşov. Sparing the city, he moved on to Cârţa where he joined forces with the Szekelys (Hungarian speaking Romanians).

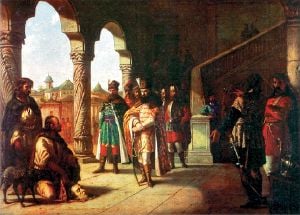

On October 18, Michael won a victory against Andrew Báthory at the Battle of Şelimbăr, giving him control of Transylvania. Báthory was killed shortly after the battle, dying at the age of 28, and Michael gave him a princely burial in the Catholic Cathedral of Alba Iulia.[12] With his enemy dead, Michael entered the Transylvanian capital at Alba Iulia, and received the keys to the fortress from Bishop Demeter Napragy, later depicted as a seminal event in Romanian historiography. Stephen Szamosközy, keeper of the Archives at the time, recorded the event in great detail. He also wrote that two days before the Diet met on October 10, Transylvanian nobles "elected Michael the voivode as Prince of Transylvania." As the Diet was assembled, Michael demanded that the estates swear loyalty to Emperor Rudolf, then to himself and thirdly to his son.[13]

Michael then began negotiating with the Emperor over his official position in Transylvania. The latter wanted the principality under direct Imperial rule with Michael acting as governor. The Wallachian voivode, on the other hand, wanted the title of Prince of Transylvania for himself and equally claimed the Partium region. Michael was, nevertheless, willing to acknowledge Habsburg overlordship.[14]

Moldavia

The Moldavian Prince Ieremia Movilă had been an old enemy of Michael, having incited Andrew Báthory to send Michael the ultimatum demanding his abdication.[15] His brother, Simion Movilă, claimed the Wallachian throne for himself and had used the title of Voivode (commander of the army) since 1595. Aware of the threat the Movilas represented, Michael had created the Banat of Buzău and Brăila in July 1598, and the new Ban was charged of keeping an alert eye on Moldavian, Tatar and Cossack moves, although Michael had been planning a Moldavian campaign for several years.[15]

On February 28, Michael met with Polish envoys in Braşov. He was willing to recognize the Polish King as his sovereign in exchange for the crown of Moldavia and the recognition of his male heirs' hereditary right over the three principalities, Transylvania, Moldavia, and Wallachia. This did not significantly delay his attack however, on April 14, 1600, Michael's troops entered Moldavia on multiple routes, the Prince himself leading the main thrust to Trotuş and Roman.[16] He reached the capital of Suceava on May 6. The garrison surrendered the citadel the next day and Michael's forces caught up with the fleeing Ieremia Movilă, who was only saved from being captured by the sacrifice of his rear-guard. Movilă took refuge in the castle of Khotyn together with his family, a handful of faithful boyars and the former Transylvanian Prince, Sigismund Báthory.[15] The Moldavian soldiers in the castle deserted, leaving a small Polish contingent as sole defenders. Under the cover of dark, sometime before June 11, Movilă managed to sneak out of the walls and across the Dniester to hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski's camp.[16]

Neighboring states were alarmed by this upsetting of the balance of power, especially the Hungarian nobility in Transylvania, who rose against Michael in rebellion. With the help of Basta, they defeated Michael at the Battle of Mirăslău, forcing the prince to leave Transylvania together with his remaining loyal troops.[17] A Polish army led by Jan Zamoyski drove the Wallachians from Moldavia and defeated Michael at Năieni, Ceptura, and Bucov (Battle of the Teleajăn River). The Polish army also entered eastern Wallachia and established Simion Movilă as ruler. Forces loyal to Michael remained only in Oltenia.[18]

Defeat and death

Michael asked again for assistance from Rudolf during a visit in Prague between February 23 and March 5, 1601, which was granted when the emperor heard that General Giorgio Basta had lost control of Transylvania to the Hungarian nobility led by Sigismund Báthory. Meanwhile, forces loyal to Michael in Wallachia led by his son, Nicolae Pătraşcu, after a first unsuccessful attempt, drove out Simion Movilă and prepared to reenter Transylvania. Michael, allied with Basta, defeated the Hungarian nobility at Gurăslău (Goroszló), but Basta then ordered the assassination of Michael, which took place near Câmpia Turzii on August 9, 1601. His head was severed from his body.

Seal of Michael the Brave

The seal comprises the coats of arms of the three Romanian principalities: In the middle, on a shield the Moldavian urus, above Wallachian eagle between sun and moon holding cross in beak, below Transylvanian coat of arms: Two meeting, standing lions supporting a sword, treading on seven mountains. The Moldavian shield is held by two crowned figures.

There are two inscriptions on the seal. First, circular, in Cyrillic "IO MIHAILI UGROVLAHISCOI VOEVOD ARDILSCOI MOLD ZEMLI," meaning "Io Michael Voivode of Wallachia, Transylvania and Moldavia Land." Second, placed along a circular arc separating the Wallachian coat from the rest of the heraldic composition, "NML BJE MLRDIE," could be translated "Through The Very Grace of God."

Legacy

Michael the Brave's rule, with its break with Ottoman rule, tense relations with other European powers and the union of the three states, was considered in later periods as the precursor of a modern Romania, a thesis which was argued with noted intensity by Nicolae Bălcescu who led the 1848 revolution in Wallachia. In 1849, Bălcescu wrote a book about Michael called Românii supt Mihai-Voievod Viteazul ("Romanians under the Rule of Michael the Brave"), published in 1860.[19] Memory of Michael's unifying achievement became a point of reference for nationalists, as well as a catalysis of various Romanian forces in order to achieve a single Romanian state. When the spirit of nationalism spread through the Balkans in the nineteenth century, Romanians started to dream of reunifying the three states, which meant gaining freedom from Austrian and Ottoman rule. Neither empire found Romanian nationalism at all to their liking. Wallachia and Moldavia gained their independence in 1856, then united as the Kingdom of Romania in 1859. After fighting with the Allies in World War I, Romania gained Transylvania following the collapse of Austria-Hungary. Finally, the three states were once more unified. Nicolae Ceauşescu, the former communist dictator, in power from 1969 until communism fell in 1989, would frequently refer to Michael the Brave and other national heroes to promote his image of Romania.[20] For centuries, the Balkans was both the border zone between competing imperial polities and a place where proxy battles were waged. Michael succeeded, briefly, in freeing the Romanian space from external domination, an achievement that properly served to inspire aspirations of freedom in a later era.

Mihai Viteazul, a commune in Cluj County, was named after Michael the Brave. Michael is also commemorated by the monks of the Athonite Simonopetra Monastery for his great contributions in the form of land and money to rebuilding the monastery which had been destroyed by a fire. Mihai Viteazul, a film by Sergiu Nicolaescu, a famous Romanian film director, is a representation of the life of the Wallachian ruler, and his will to unite the three Romanian principalities (Wallachia, Moldavia, and Transylvania) in one country.[21]

His head was buried under a slab in Dealu Monastery, "topped by a bronze crown … the inscription reads, 'To he who first united our homeland, eternal glory'".[1]

The Order of Michael the Brave, Romania's highest military decoration, was named after Michael.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Burford (2001), 115.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 182.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 183.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Giurescu (2007), 186.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 185.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 189.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 190.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 191.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 192.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Giurescu, 193.

- ↑ Giurescu, 194.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 195.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 196.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 196–97.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Giurescu (2007), 198.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Giurescu (2007), 199.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 201.

- ↑ Giurescu (2007), 200.

- ↑ Nicolae Bălcescu and Paul Cornea, Românii supt Mihai-Voievod Viteazul (Bucharest, RO: Editura Tineretului, 1967).

- ↑ Roper (2000), 47.

- ↑ Internet Movie Database, Mihai Viteazul (1970). Retrieved August 21, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burford, Tim, and Dan Richardson. 2001. The Rough Guide to Romania. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858287027.

- Giurescu, Constantin C. 1937. Istoria românilor 2. Bucureşti, RO: ALL. ISBN 9789736841699.

- Hentea, Călin. 2007. Brief Romanian Military History. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810858206.

- Klepper, Nicolae. 2002. Romania: An Illustrated History. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 9780781809351.

- Roper, Steven D. 2000. Romania: The Unfinished Revolution. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic. ISBN 9789058230287.

- Treeptow, Kurt W. 1997. A History of Romania. Iași, RO: Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 9789739809108.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.