John Hunyadi

John Hunyadi (Medieval Latin: Ioannes Corvinus; Hungarian: Hunyadi JĂĄnos; Romanian: Iancu or Ioan de Hunedoara) (c. 1387 â August 11, 1456), nicknamed the White Knight, was a Voivode (Ruler) of Transylvania (from 1441), captain-general (1444â1446) and regent (1446â1453) of the Kingdom of Hungary, with a distinguished military career and one of the most renowned kings of the country. John Hunyadi is considered a defender of Christendom for inflicting several defeats on the Ottomans including at Nis (1443) and for halting their advance into Europe, at least until seventy years or so after his death. Pope Calixtus III declared him an 'Athlete of Christ'.

Facing what was at the time the only standing army in Europe, the Janissary corps, he established his own regular army, which served as a model for others in Europe. His emphasis on tactics and strategy instead of over-reliance on frontal assaults and mĂȘlĂ©es represented a significant contribution to military science. After a final victory against the Turks from July 21-22, 1456, during the Siege of Belgrade, he caught the plague and died. John Hunyadi has hero status in the national discourse of several statesâRomania, Moldavia and Hungary. Each in its own way has claimed him as their own. Hunyadi's role, significant for the whole of Europe, lifted him from the local and even from the regional into the context of the whole of European civilization, to which he belongs as much as he does to any single national tradition.

Origin

John was born into a noble family in 1387 (or 1400 according to some sources) as the son of Vojk (Voicu),[1] a boyar from Wallachia and Erzsébet Morzsinay the daughter of a Hungarian noble family. John's grandfather was named Sorb (also spelled as Serbu or Serbe), a Romanian Knyaz from the Banate of Szörény (Severin). An alternative theory states that John Hunyadi's parental line was of Cuman descent on his father's side. A theory issued at the end of the nineteenth century claims that Sorb, John's grandfather, was originally from Serbia,[2] an origin not attested by contemporary sources. Sorb had two other sons: Mogos and Radul. What is certain is that Vojk, John's father, took the family name of Hunyadi when he received the estate around the Hunyad Castle from King Sigismund, in 1409, ennobled as count of Hunyad.

John's mother was ErzsĂ©bet SzilĂĄgyi (Romanian: Elisabeta MÄrgean) of CinciĆ, the daughter of a small Hungarian noble family from Hunyad-Hunedoara.

John married ErzsĂ©bet SzilĂĄgyi (c. 1410-1483), a Hungarian noblewoman, also of high-rank (SzilĂĄgy being the name of a county overlapping with present-day SÄlaj).

The epithet Corvinus was first used by the biographer of his son Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, but is sometimes also applied to John. The epithet is also related to a legend: during a trip with his parents, as they slept, a six- or seven-years old John was said to have been playing with a precious medallion that the emperor Sigismund had given his father. According to legend, when a rook stole the medallion, young John used a bow and arrow to shoot the bird.

Another legend, thought to be discreetly distributed by John himself, was that he was the son of Sigismund of Luxembourg,[3] whose faithful soldier his father was for two decades. This tale helped him secure more legitimacy for his descendants to the throne of the Kingdom, to which John, despite all his services, could not accedeâhaving no royal origin. Widely respected in Europe, he still gathered rivals throughout his lifetime, and was the object of the Ottoman Empire's hatred. Hunyadi has sometimes been confused with an elder brother or cousin John, himself a Severin Ban (the elder John died about 1440).

Rise

With Sigismund and in the disputed elections

While still a youth, the younger John Hunyadi entered the retinue of Sigismund, who appreciated his qualities. (He also was the King's creditor on several occasions.) He accompanied the monarch to Frankfurt, in Sigismund's quest for the Imperial crown in 1410, took part in the Hussite Wars in 1420, and in 1437 drove the Ottomans from Semendria. For these services he received numerous estates and a seat in the royal council. In 1438 King Albert II made Hunyadi Ban[3] of Severin. Lying south of the defensible southern frontiers of Hungary, the Carpathians and the Drava/Sava/Danube complex, the province was subject to constant harassment by Ottoman forces.

Upon the sudden death of Albert in 1439, Hunyadi, arguably feeling Hungary needed a warrior king, lent his support to the candidature of young King of Poland WĆadysĆaw III of Varna in 1440, and thus came into collision with the powerful Ulrich II of Celje, the chief supporter of Albert's widow Elizabeth II of Bohemia and her infant son, Ladislaus Posthumus of Bohemia and Hungary. He took a prominent part in the ensuing civil war and was rewarded by WĆadysĆaw with the captaincy of the fortress of Belgrade and the governorship of Transylvania. He shared the latter dignity with MihĂĄly Ăjlaki.

First battles of the Balkans

The burden of the Ottoman War now rested with him. In 1441 he delivered Serbia by the victory of Semendria. In 1442, not far from Nagyszeben, on which he had been forced to retire, he annihilated an immense Ottoman presence, and recovered for Hungary the suzerainty of Wallachia. In February 1450, he signed an alliance treaty with Bogdan II of Moldavia.

In July, he vanquished a third Turkish army near the Iron Gates. These victories made Hunyadi a prominent enemy of the Ottomans and renowned throughout Christendom, and stimulated him in 1443 to undertake, along with King WĆadysĆaw, the famous expedition known as the long campaign. Hunyadi, at the head of the vanguard, crossed the Balkans through the Gate of Trajan, captured NiĆĄ, defeated three Turkish pashas, and, after taking Sofia, united with the royal army and defeated Sultan Murad II at Snaim. The impatience of the king and the severity of the winter then compelled him (February 1444) to return home, but not before he had utterly broken the Sultan's power in Bosnia, Herzegovina, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Albania.

No sooner had he regained Hungary than he received tempting offers from Pope Eugene IV, represented by the Legate Julian Cesarini, from ÄuraÄ BrankoviÄ, despot of Serbia, and Gjergj Kastrioti, prince of Albania, to resume the war and realize his ideal of driving the Ottomans from Europe. All the preparations had been made when Murad's envoys arrived in the royal camp at Szeged and offered a ten years' truce on advantageous terms. BrankoviÄ bribed Hunyadiâhe gave him his vast estates in Hungaryâto support the acceptance of the peace. Cardinal Julian Cesarini found a traitorous solution. The king swore that he would never give up the crusade, so all future peace and oath was automatically invalid. After this Hungary accepted the Sultan's offer and Hunyadi in WĆadysĆaw's name swore on the Gospels to observe them.

Battle of Varna

Two days later Cesarini received tidings that a fleet of Venetian galleys had set off for the Bosporus to prevent Murad (who, crushed by his recent disasters, had retired to Anatolia) from recrossing into Europe, and the cardinal reminded the King that he had sworn to cooperate by land if the western powers attacked the Ottomans by sea. In July the Hungarian army recrossed the frontier and advanced towards the Black Sea coast in order to march to Constantinople escorted by the galleys.

BrankoviÄ, however, fearful of the sultan's vengeance in case of disaster, privately informed Murad of the advance of the Christian host, and prevented Kastrioti from joining it. On reaching Varna, the Hungarians found that the Venetian galleys had failed to prevent the transit of the Sultan; indeed, the Venetians transported the Sultan's army (and received, according to legend, one gold for each soldier shipped over). Hunyadi, on November 10, 1444, confronted the Turks with four times the Hungarian forces. Nevertheless, victory was still possible in the Battle of Varna as Hunyadi with his superb military skills managed to route both flanks of the Sultan's army. At this point, however, king WĆadysĆaw, who up to that point had remained in the background and relinquished full leadership to Hunyadi, assumed command and with his bodyguards carried out an all-out attack on the elite troops of the Sultan, the Janissaries. The Janissaries readily massacred the king's men, also killing the king, exhibiting his head on a pole. The king's death caused disarray in the Hungarian army, which was subsequently routed by the Turks; Hunyadi himself narrowly escaped. On his way home, Vlad II Dracul of Wallachia imprisoned Hunyadi; only the threats of the palatine of Hungary brought the voivode, theoretically an ally of Hunyadi against the Turks, to release him.

Regent of the Kingdom of Hungary

Brief personal rule

At the diet which met in February 1445 a provisional government consisting of five Captain Generals was formed, with Hunyadi receiving Transylvania and four counties bordering on the Tisza, called the Partium or Körösvidék, to rule. As the anarchy resulting from the division became unmanageable, Hunyadi was elected regent of Hungary (Regni Gubernator) on June 5, 1446, in the name of Ladislaus V and given the powers of a regent. His first act as regent was to proceed against the German king Frederick III, who refused to release Ladislaus V. After ravaging Styria, Carinthia, and Carniola and threatening Vienna, Hunyadi's difficulties elsewhere compelled him to make a truce with Frederick for two years.

In 1448 he received a golden chain and the title of Prince from Pope Nicholas V, and immediately afterwards resumed the war with the Ottomans. He lost the two-day Second Battle of Kosovo (October 7-10, 1448), owing to the treachery of Dan II of Wallachia, then pretender to the throne, and of his old rival BrankoviÄ, who intercepted Hunyadi's planned Albanian reinforcements led by Gjergj Kastrioti, preventing them from ever reaching the battle. BrankoviÄ also imprisoned Hunyadi for a time in the dungeons of the fortress of Smederevo, but he was ransomed by his countrymen and, after resolving his differences with his powerful and numerous political enemies in Hungary, led a punitive expedition against the Serbian prince, who was forced to accept harsh terms of peace.

In 1450 Hunyadi went to the Hungarian capital of Pozsony to negotiate with Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III the terms of the surrender of Ladislaus V, but no agreement could be reached. Several of John Hunyadi's enemies, including Ulrich II of Celje, accused him of conspiracy to overthrow the King. In order to defuse the increasingly volatile domestic situation, he relinquished his regency and the title of regent.

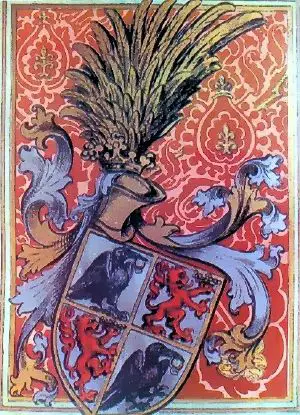

On his return to Hungary at the beginning of 1453, Ladislaus named him count of Beszterce and Captain General of the kingdom. The king also expanded his coat-of-arms with the so-called Beszterce Lions.

Belgrade campaign and death

Meanwhile, the Ottoman issue had again become acute, and, after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, it seemed natural that Sultan Mehmed II was rallying his resources in order to subjugate Hungary.[4] His immediate objective was Belgrade. Hunyadi arrived at the siege of Belgrade at the end of 1455, after settling differences with his domestic enemies. At his own expense, he restocked the supplies and arms of the fortress, leaving in it a strong garrison under the command of his brother-in-law MihĂĄly SzilĂĄgyi and his own eldest son LĂĄszlĂł Hunyadi. He proceeded to form a relief army, and assembled a fleet of two hundred ships. His main ally was the Franciscan friar, Giovanni da Capistrano, whose fiery oratory drew a large crusade made up mostly of peasants. Although relatively ill-armed (most were armed with farm equipment, such as scythes and pitchforks) they flocked to Hunyadi and his small corps of seasoned mercenaries and cavalry.

On July 14, 1456, the flotilla of corvettes assembled by Hunyadi destroyed the Ottoman fleet. On July 21, Szilågyi's forces in the fortress repulsed a fierce assault by the Rumelian army, and Hunyadi pursued the retreating forces into their camp, taking advantage of the Turkish army's confused flight from the city. After fierce but brief fighting, the camp was captured, and Mehmet raised the siege and returned to Istanbul. With his flight began a 70 year period of relative peace on Hungary's southeastern border. However, plague broke out in Hunyadi's camp three weeks after the lifting of the siege, and he died on August 11. He was buried inside the (Roman Catholic) Cathedral of Alba Iulia (Gyulafehérvår), next to his elder brother John.

Legacy

The rise of nationalism has led to hero images of John Hunyadi in the discourse of several local nationalitiesâeach in its own way has claimed him as their own. Along with his son Matthias Corvinus, John has acquired a presence in modern Romania's political culture (images that focus on the Vlach origin rather than their careers within Hungary or on their presence as outsiders in the politics of Wallachia and Moldavia, although Hunyadi was responsible for establishing the careers of both Stephen III of Moldavia and the controversial Vlad III of Wallachia). John Hunyadi is traditionally considered a national hero in Hungary.

Among John's noted qualities, is his regional primacy in recognizing the insufficiency and unreliability of the feudal levies, instead regularly employing large professional armies. His notable contribution to the development of the science of European warfare included the emphasis on tactics and strategy in place of over-reliance on frontal assaults and mĂȘlĂ©es. France says that Hunyadi's tactics "infantry ...anchored their positions with carts and canon, and used handguns to fight off cavalry attack" and that subsequently the Janissaries "soon became heavily armed with the new gunpowder weapons" since "the Ottoman war machine" was at the time "as flexible as that of any Western state."[5]

Although he remained illiterate until late in life (something not uncommon during the age he lived in), his diplomatic, strategic, and tactical skills allowed him to serve his country well. After his death, Pope Callixtus III stated that "the light of the world has passed away," considering his defense of Christendom against the Ottoman threat.

Popular Culture

- John Hunyadi features in the game Legendary Warriors, where he is portrayed as a father to his two sons Matthias Corvinus and LĂĄszlĂł Hunyadi, and is also a father figure to his niece Diana. He is also shown to be one of the greatest and most respected commanders of the western forces. He also has a tendency to become detached from battles by grief or joy, and another general has to remind him of the battle. He wields claymore.

Notes

- â Vojk is alternatively spelled as Voyk or Vajk in English, Voicu in Romanian, Vajk in Hungarian.

- â Borovszky Samu, MagyarorszĂĄg vĂĄrmegyĂ©i Ă©s vĂĄrosai (Budapest, HU: Dovin, 1989, ISBN 9630265664).

- â 3.0 3.1 A. AldĂĄsy, JĂĄnos Hunyady The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- â Hunyadi may have aided the capture of Constantinople by sending military advisors to assist Mehmed II. He regarded the Orthodox Church as heretical and thought that the Turkish victory might hasten its demise.

- â France, p. 282.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Engel, PĂĄl. 2001. The realm of St. Stephen: a history of medieval Hungary, 895-1526. London, UK: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781860640612

- France, John. 2005. The Crusades and the expansion of Catholic Christendom, 1000-1714. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 9780415371285

- Held, Joseph. 1985. Hunyadi: legend and reality. East European monographs, no. 178. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs. ISBN 9780880330701

- MureĆanu, Camil. 2001. John Hunyadi: defender of Christendom. IaĆi, RO: Center for Romanian Studies. ISBN 9789739432184

- Nicolle, David, and Angus McBride. 2004. Hungary and the fall of Eastern Europe 1000-1568. Men-at-arms series, 195. Oxford, UK: Osprey. ISBN 9780850458336

- Varga, Domokos. 1982. Hungary in greatness and decline: the 14th and 15th centuries. Atlanta, GA: Hungarian Cultural Foundation. ISBN 9780914648116

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.