Janissary

The Janissaries (derived from Ottoman Turkish ينيچرى (yeniçeri), meaning "new soldier") comprised infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops and bodyguard. The force originated in the fourteenth century and mainly comprised of non-Muslim boys often captured in war and mainly from the Balkans;[1] it was abolished by Sultan Mahmud II in 1826 due to its increased wealth, power and frequent revolts against the Sultan. The Ottoman Empire used Janissaries in all its major campaigns, including the 1453 capture of Constantinople, the defeat of the Egyptian Mamluks and wars against Hungary and Austria. Janissary troops were always led to the battle by the Sultan himself, and always had a share of the booty. The Janissary were the first full-time, trained standing army since the days of the Roman Empire. They are also credited with establishing the first military music bands. While initially well equipped and technologically innovative, towards the end of the corps it failed to modernize. On the other hand, the creation of standing armies in Europe may well have been inspired by the success of the Janissary corps. It has been suggested, too, that the revolts took place because the corps saw itself as guardian of good governance, and that the role of the military in the modern nation state of Turkey is a continuation of this legacy.[2] Whether this is or is not an acceptable role for an army, it was political expediency that ended the corps's existence. European rulers saw the advantage of regular armies and established their own, drawing on the Janissary model of organization although not of recruitment.

Origin of the Janissaries

Sultan Murad I of the fledgling Ottoman Empire founded the units around 1365. It was initially formed of Dhimmi (non-Muslims, originally exempted from the military service), especially Christian youth and prisoners of war, reminiscent of Mamelukes. Sultan Murad may have also used futuwa groups as a model. He may have distrusted the voluntary soldiers, and wanted to forge a corps of soldiers loyal to himself. According to Nicolle and Hook, conscription into the Janissary corps enabled minorities, "such as the Bogomils of Bposnia" who found themselves under Muslim rule to join the elite, something that under Christian rule they had "never been able to do" facing persecution instead. Some of those recruited already possessed military skill. Thus, "by giving existing Christian military classes a continuing role while offering the possibility of further advancement if they converted to Islam, the Ottomans absorbed much of the Byzantine Greek and Slav elites, who in turn soon had a clear influence on the development of Ottoman military traditions."[3]

Such Janissaries became the first Ottoman standing army, replacing forces that mostly comprised tribal ghazis, whose loyalty and morale could not always be trusted.

As corps other than the infantry were added, the totality of the Ottoman standing army corps was called Kapıkulu, however the term Janissary, which formally refers to one of the Kapıkulu corps is often used interchangeably (albeit incorrectly) for all of the Ottoman Kapıkulu Corps.

Significance of the Janissaries

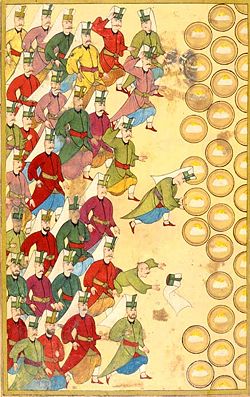

The Janissary corps were significant in a number of ways. The Janissaries wore uniforms, were paid in cash as regular soldiers, and marched to distinctive music, the Mehter, similar to a modern marching band. All of these features set the Janissaries apart from most soldiers of the time.

The Ottomans were the first state to maintain a standing army in Europe since the Roman Empire. The Janissaries have been likened to the Roman Praetorian Guard and they had no equivalent in the Christian armies of the time, where the feudal lords raised troops during wartime.[4] A janissary regiment was effectively the soldier's family. They lived in their barracks and served as policemen and firefighters during peacetime.[5]

Christian rulers such as John Hunyadi having fought against the Janissaries saw the advantage of a regular, well trained army and formed their own.

The Janissary corps was also distinctive in the regular payment of a cash salary to the troops, and differed from the contemporary practice of paying troops only during wartime. The Janissaries were paid quarterly and the Sultan himself, after authorizing the payment of the salaries, dressed as a Janissary, visited the barracks and received his salary as a regular trooper of the First Division.

The Janissary force became particularly significant when the foot soldier carrying firearms proved more effective than the cavalry equipped with sword and spear. Janissaries adopted firearms very early, starting in fifteenth century. By the sixteenth century, the main weapon of the Janissary was the musket. Janissaries also made extensive use of early grenades and hand cannon, such as the Abus gun.

The auxiliary support system of the Janissaries also set them apart from their contemporaries. The Janissaries waged war as one part of a well organized military machine. The Ottoman army had a corps to prepare the road, a corps to pitch the tents ahead, a corps to bake the bread. The cebeci corps carried and distributed weapons and ammunition. The Janissary corps had its own internal medical auxiliaries: Muslim and Jewish surgeons who would travel with the corps during campaigns and had organized methods of moving the wounded and the sick to traveling hospitals behind the lines.

These differences, along with a war-record that was impressive, made the Janissaries into a subject of interest and study by foreigners in their own time. Although eventually the concept of the modern army incorporated and surpassed most of the distinctions of the Janissary, and the Ottoman Empire dissolved the Janissary corps, the image of the Janissary has remained as one of the symbols of the Ottomans in the western psyche.

In modern times, although the Janissary corps no longer exists as a professional fighting force, the tradition of Mehter music is carried on as a cultural and tourist attraction.

Reputation in Europe

The image of the "Terrible Turk," suggest Nicolle and Hook, has hindered objective European accounts of the Janissaries. However, a writer in the late sixteenth century suggested a number of reasons for their success, including their "devotion to war, taking the offensive, a lack of interest in fixed fortifications, well trained soldiers, strong discipline, use of ruses as well as direct attack, good commanders and no wasting time on amusements." Another commentator "added the cleanliness of their camps, where there was neither gambling, drinking nor swearing, and where there were proper latrines and an efficient corps of water-carriers who followed the army into battle and helped the wounded."[6]

Recruitment, training and status

The first Janissary units comprised war captives and slaves, selecting one in five for enrollment in the ranks (Pencik rule). After the 1380s Sultan Mehmet I filled their ranks with the results of taxation in human form called devshirmeh: the Sultan's men conscripted a number of non-Muslim, usually Christian Balkan boys, taken at birth at first at random, later, by strict selection—to be converted to Islam and trained.

Nicolle and Hook point out that while at this time most Christians would "simply kill their Turkish prisoners" the Ottomans "adopted the traditional Muslim practice of not harming POWs under the age of 20, but enslaving them as booty."[3]

Initially they favored Greeks (who formed the largest part of the first units) and Albanians (who besides supplied with gendarmes), usually selecting about one boy from forty houses, but the numbers could be changed to correspond with the need for soldiers. Boys aged 14-18 were preferred, though ages 8-20 could be taken.

As the Turks expanded their borders, the devshirmeh was extended to also include Bulgarians, Romanians, Armenians and Serbs at first, but later even Poles, Ukrainians and southern Russians.

The Janissaries started accepting enrollment from outside the devshirmeh system first during the reign of Sultan Murad III (1546-1595) and completely stopped enrolling devshirmeh in the seventeenth century. After this period, volunteers were enrolled, mostly of Muslim origin.

Janissaries trained under strict discipline with hard labor and in practically monastic conditions in acemi oğlan ("rookie" or "cadet") schools, where they were expected to remain celibate. They were also expected to convert to Islam. All did, as Christians were not allowed to bear arms in the Ottoman Empire until the nineteenth century. Unlike other Muslims, they were expressly forbidden to wear beards (a Muslim custom), only a moustache. These rules were obeyed by Janissaries, at least until eighteenth century when they also began to engage in other crafts and trades, breaking another of the original rules.

For all practical purposes, Janissaries belonged to the Sultan, carrying the title kapıkulu ("door slave") indicating their collective bond with the Sultan. Janissaries were taught to consider the corps as their home and family, and the Sultan as their de facto father. Only those who proved strong enough earned the rank of true Janissary at the age of twenty-four or twenty-five. The regiment inherited the property of dead Janissaries, thus amassing wealth (like religious orders and foundations enjoying the 'dead hand').

Janissaries also learned to follow the dictates of the dervish saint Hajji Bektash Wali, disciples of whom had blessed the first troops. Bektashi served as a kind of chaplain for Janissaries. In this and in their secluded life, Janissaries resembled Christian military orders like the Johannites of Rhodes.

In return for their loyalty and their fervor in war, Janissaries gained privileges and benefits. They received a cash salary, received booty during wartime and enjoyed a high living standard and respected social status. At first they had to live in barracks and could not marry until retirement, or engage in any other trade but by the mid-eighteenth century they had taken up many trades and gained the right to marry and enroll their children in the corps and very few continued to live in the barracks.[5] Many of them became administrators and scholars. Retired or discharged Janissaries received pensions and their children were also looked after. This evolution away from their original military vocation was the essence of the system's demise.

Janissary corps

The full strength of the Janissary troops varied from maybe 100 to more than 200,000. According to David Nicolle, the number of Janissaries in the fourteenth century was 1,000, and estimated to be 6,000 in 1475, whereas the same source estimates 40,000 as the number of Timariot, the provincial soldiers. After the defeat in 1699, the number was reduced, but it was increased in the eighteenth century to 113,400 soldiers according to Ottoman, but most were not actual soldiers and were accepted into the army through corrupt means and were only taking salary.

The corps was organized in ortas (equivalent to regiment) An orta was headed by çorbaci. All ortas together would comprise the proper Janissary corps and its organization named ocak (literally "hearth"). Suleiman I had 165 ortas but the number over time increased to 196. The Sultan was the supreme commander of the Army and the Janissaries in particular, but the corps was organized and led by their supreme ağa (commander). The corps was divided into three sub-corps:

- the cemaat (frontier troops; also spelled jemaat), with 101 ortas

- the beyliks or beuluks (the Sultan's own bodyguard), with 61 ortas

- the sekban or seirnen, with 34 ortas

In addition there was also 34 ortas of the ajemi (cadets).

Originally Janissaries could be promoted only through seniority and within their own orta. They would leave the unit only to assume command of another. Only Janissaries' own commanding officers could punish them. The rank names were based on positions in a kitchen staff or troop of hunters, perhaps to emphasize that Janissaries were servants of the Sultan.

In the first centuries, Janissaries were expert archers, but they adopted firearms as soon as such became available during the 1440s. The siege of Vienna in 1529 confirmed the reputation of their engineers, e.g. sapping and mining. In melee combat they used axes and sabers. Originally in peacetime they could carry only clubs or cutlasses, unless they served in border troops. Local Janissaries, stationed in a town or city for a long time, were known as yerliyyas.

The Ottoman empire used Janissaries in all its major campaigns, including the 1453 capture of Constantinople, the defeat of the Egyptian Mamluks and wars against Hungary and Austria. Janissary troops were always led to the battle by the Sultan himself, and always had a share of the booty.

Janissaries’ reputation increased to the point that by 1683, Sultan Mehmet IV abolished the devshirmeh as increasing numbers of originally Muslim Turkish families had already enrolled their own sons into the force hoping for a lucrative career. Every governor wanted to have his own Janissary troops.

Equipment: Supplied by Protestant Europe

While the Pope tried to prevent the sale of arms to the Janissary, from the sixteenth century on it was the Protestant Dutch and the English who were their main suppliers. There were some sales in the opposite direction, as "there was demand for high-quality Turkish gun barrells" in Europe.[7]

Janissary revolts

As Janissaries became aware of their own importance they began to desire a better life. In 1449 they revolted for the first time, demanding higher wages, which they obtained. Similar scenarios took place a number of times during the following centuries. As the Janissaries were amassing more power and wealth, they gradually turned into a corrupt and largely useless caste, wielding an influence akin to that of the Roman Praetorian Guard. Finally, Mahmud II succeeded in forcibly disbanding them in 1826. The Ottomans then established a new army on European lines, employing European instructors to train their troops. Ironically, perhaps, the Europeans may well have learnt the value of possessing a professional, trained army from the success of the Janissary corps.

An alternative view of the Janissary revolts argue that the Corp "acted as a pressure group to force the Sultans (only those who were preoccupied with the Harem, neglecting the State Duties, or were under the dictates of the Queen Mother-Valide Sultan) to behave and act in the interest of the Turkish nation."[8] In this view, the way in which the army of the modern nation state of Turkey has regarded itself as the guardian both of the state's secular constitution and of democracy, derives in part from the legacy of the corps, thus:

- The Turkish Army is unique in many ways. It traces a part of its legacy from the Ottoman period. The period, when the Janissary corps existed during the latter half of the fourteenth century until 1826. It has not changed much of its character of the role it has contemplated in assigning for itself. That is, GUARDIAN OF THE TURKISH NATION BOTH IN TIMES OF PEACE AND WAR, AND AGAINST INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL DANGER.[8]

According to Yildiz, this role is assigned to the military under the constitution.

Janissary music

The Janissaries pioneered military bands. Their military march music is characteristic because of its powerful, often shrill sound combining davul (bass drum), zurna (a loud oboe), naffir (trumpet), bells, triangle, and cymbals (zil), among others. Janissary music influenced European classical musicians like Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Ludwig van Beethoven, both of whom composed marches in the Turkish style (Mozart's Piano Sonata in A major, K. 331 (c. 1783), and Beethoven's incidental music for The Ruins of Athens, Op. 113 (1811), and the final movement of Symphony no. 9).

In 1952, the Janissary military band, Mehter, was organized again under the auspices of the Istanbul Military Museum. They have performances during some national holidays as well as in some parades during days of historical importance.

Notes

- ↑ Willocks (2006). Tim Willocks fictional character, Mattias Tannhauser was captured as a child and trained as a janissary.

- ↑ Çakmak (2008). History of Turkish Political Life Assyrian International News Agency. Retrieved July 18, 2008. "In the year 1961, the army left behind the most democratic constitution of Turkish political life which allowed the rise of new views in the left and right wings," says Çakmak who describes the army's role as safeguarding "Kemalist principles."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nicolle and Hook (1995), p. 4.

- ↑ Kinross (1977), p. 52.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Goodwin (1997), pp. 59, 179-181.

- ↑ Nicolle and Hook (1995), p. 3.

- ↑ Nicolle and Hook (1995), p. 20.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Halit Yildiz (1998), Turkish Army, Democracy and Islam The Globe.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- 1994. Soldiers of the East. Bethesda, MD: Discovery Enterprises Group. ISBN 9781563311871

- Goodwin, Godfrey. 1997. The Janissaries. London, UK: Saqi Book Depot. ISBN 9780863560552

- Hickok, Michael Robert. 1997. Ottoman military administration in eighteenth-century Bosnia. Ottoman Empire and its heritage. v. 13. Leiden, NL: Brill. ISBN 9789004106895

- Kinross, Patrick Balfour. 1977. The Ottoman centuries: the rise and fall of the Turkish empire. New York, NY: Morrow. ISBN 9780688030933

- Nicolle, David, and Christa Hook. 1995. The Janissaries. Elite series, 58. London, UK: Osprey. ISBN 9781855324138

- Willocks, Tim. 2006. The Religion. New York, NY: Sarah Crichton Books. ISBN 9780374248659

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.