| Sierra Nevada | |

| Range | |

Little Lakes Valley: Typical east side terrain

| |

| Country | United States |

|---|---|

| States | California, Nevada |

| Highest point | Mount Whitney |

| - elevation | 14,505 feet (4,421 meters) |

| - coordinates | |

| Length | 400 miles (644 km), North-South |

| Geology | batholith, igneous |

| Period | Triassic |

The Sierra Nevada (Spanish for "snowy mountain range") is a major mountain range of the western United States. It is also known informally as the Sierra, the High Sierra, and the Sierras. It runs along the eastern edge of California, overlapping into neighboring Nevada in some areas. The range stretches 400 miles (650 km) north to south and is part of the Cascade-Sierra Mountains province, and the even larger Pacific Mountain System. It is bounded on the west by California's Central Valley, and on the east by the Great Basin. The range varies from about 80 miles wide at Lake Tahoe to about 50 miles wide in the south.

The Sierra Nevada, home to the largest trees in the world—the Giant Sequoias—hosts four national parks, nine national forests, 32 state parks, and approximately 5,300 square miles (13,700 km²) of protected wilderness areas. It is also the location of Mount Whitney, the highest summit in the contiguous United States at 14,505 feet (4,421 m).

The range has had a major influence on the climate, agriculture, economics, population spread, and settlement patterns of the Western United States and has been a major facet of life for generations of Native Americans. Home to a great diversity of plant and animal life, its magnificent skyline and variety of landscapes lead it to be considered by many as one of the most beautiful natural features of the United States.

Geography

The Sierra Nevada stretches 400 miles (650 km), from Fredonyer Pass in the north to Tehachapi Pass in the south.[1] It is bounded on the west by California's Central Valley, and on the east by the Great Basin.

Physiographically, it is a section of the Cascade-Sierra Mountains province, which in turn is part of the larger Pacific Mountain System physiographic division.

In west-east cross section, the Sierra is shaped like a trapdoor: the elevation gradually increases on the west slope, while the east slope forms a steep escarpment.[1] Thus, the crest runs principally along the eastern edge of the Sierra Nevada range. Rivers flowing west from the Sierra Crest eventually drain into the Pacific Ocean, while rivers draining east flow into the Great Basin and do not reach any ocean.[2] However, water from several streams and the Owens River is redirected to the city of Los Angeles. Thus, by artificial means, some east-flowing river water does make it to the Pacific Ocean.

There are several notable geographical features in the Sierra Nevada:

- Lake Tahoe is a large, clear freshwater lake in the northern Sierra Nevada, with an elevation of 6,225 feet (1,897 m) and an area of 191 square miles (489 km²).[3] Lake Tahoe lies between the main Sierra and the Carson Range, a spur of the Sierra.[3]

- Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite Valley, Kings Canyon, Tehipite Valley and Kern Canyon are the most well-known of many beautiful, glacially-scoured canyons on the west side of the Sierra.

- Yosemite National Park is filled with stunning features, such as waterfalls and granite domes.

- Mount Whitney, at 14,505 feet (4,421 m),[4] is the highest point in the contiguous United States. Mt. Whitney is on the eastern border of Sequoia National Park.

- Groves of Giant Sequoias Sequoiadendron giganteum occur along a narrow band of altitude on the western side of the Sierra Nevada. Giant Sequoias are the most massive trees in the world.[5]

The height of the mountains in the Sierra Nevada gradually increases from north to south. Between Fredonyer Pass and Lake Tahoe, the peaks range from 5,000 feet (1,524 m) to 8,000 feet (2,438 m). The crest near Lake Tahoe is roughly 9,000 feet (2,700 m) high, with several peaks approaching the height of Freel Peak (10,881 feet, 3,316 m), including Mount Rose (10,776 feet, 3,285 m), which overlooks Reno from the north end of the Carson Range. The crest near Yosemite National Park is roughly 13,000 feet (4,000 m) high at Mount Dana and Mount Lyell, and the entire range attains its peak at Mount Whitney (14,505 feet, 4,421 m). South of Mount Whitney, the range diminishes in elevation, but there are still several high points like Florence Peak (12,405 feet, 3,781 m) and Olancha Peak (12,123 feet, 3,695 m). The range still climbs almost to 10,000 feet (3,048 m) near Lake Isabella, but south of the lake, the peaks reach only to a modest 8,000 feet (2,438 m).[6][7]

Geology

The well-known granite that makes up most of the southern Sierra started to form in the Triassic period. At that time, an island arc collided with the West coast of North America and raised a set of mountains, in an event called the Nevadan orogeny.[8] This event produced metamorphic rock. At roughly the same time, a subduction zone began to form at the edge of the continent. This means that an oceanic plate started to dive beneath the North American plate. Magma from the melting oceanic plate rose in plumes (plutons) deep underground, their combined mass forming what is called the Sierra Nevada batholith. These plutons formed at various times, from 115 million to 87 million years ago.[9] By 65 million years ago, the proto-Sierra Nevada was worn down to a range of rolling low mountains, a few thousand feet high.

Twenty million years ago, crustal extension associated with the Basin and Range Province caused extensive volcanism in the Sierra.[10] About 4 million years ago, the Sierra Nevada started to form and tilt to the west. Rivers started cutting deep canyons on both sides of the range. The Earth's climate cooled, and ice ages began about 2.5 million years ago. Glaciers carved out characteristic U-shaped canyons throughout the Sierra. The combination of river and glacier erosion exposed the uppermost portions of the plutons emplaced millions of years before, leaving only a remnant of metamorphic rock on top of some Sierra peaks.

Uplift of the Sierra Nevada continues today, especially along its eastern side. This uplift causes large earthquakes, such as the Lone Pine earthquake of 1872.

Ecology

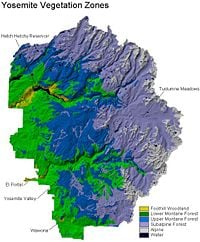

The Ecology of the Sierra Nevada is diverse and complex: the plants and animals are a significant part of the scenic beauty of the mountain range.The combination of climate, topography, moisture, and soils influence the distribution of ecological communities across an elevation gradient from 1,000 feet (300 m) to over 14,000 feet (4,300 m). Biotic zones range from scrub and chaparral communities at lower elevations, to subalpine forests and alpine meadows at the higher elevations. There are numerous hiking trails in the Sierra Nevada, which provide access for exploring the different vegetation zones.[11]

The western and eastern Sierra Nevada have substantially different species of plants and animals, because the east lies in the rain shadow of the crest. The plants and animals in the east are thus adapted to much drier conditions.[9]

Biotic zones

The Sierra Nevada is divided into a number of biotic zones. The climate across the north-south axis of the range varies somewhat: The boundary elevations of the biotic zones move by as much as 1000' from the north end to the south end of the range.[9] While the zones are the same for the eastern and western sides, the range varies due in large part to precipitation.

- The Pinyon pine-Juniper woodland, 5,000-7,000 ft (1,500-2,100 m) east side only

- Notable species: Pinyon Jay, Desert Bighorn Sheep

- The lower montane forest, 3,000-7,000 ft (1,000-2,100 m) west side, 7,000-8,500 ft (2,100-2,600 m) east side

- Notable species: Ponderosa pine and Jeffrey pine, California black oak, Incense-cedar, Giant Sequoia, Dark-eyed Junco, Mountain Chickadee, Western gray squirrel, Mule deer, American black bear

- The upper montane forest, 7,000-9,000 ft (2,100-2,700 m) west side, 8,500-10,500 ft (2,600-3,100 m) east side

- Notable species: Lodgepole pine, Red Fir, Mountain Hemlock, Sierra Juniper, Hermit Thrush, Sage Grouse, Great Grey Owl, Golden-mantled Ground Squirrel, Marten

- The subalpine forest, 9,000-10,500 ft (2,700-3,100 m) west side, 10,500-11,500 ft (3,100-3,500 m) east side

- Notable species: Whitebark pine and Foxtail pine, Clark's Nutcracker

- The alpine region >10,500 ft (>3,100 m) west side, >11,500 ft (>3,500 m) east side

Wetlands

Wetlands in the Sierra Nevada occur in valley bottoms throughout the range, and are often hydrologically linked to nearby lakes and rivers through seasonal flooding and groundwater movement. Meadow habitats, distributed at elevations from 3,000 feet to 11,000 feet, are generally wetlands, as are the riparian habitats found on the banks of numerous streams and rivers.[12]

The Sierra contain three major types of wetland:

- Riverine

- Lacustrine

- Palustrine

Each of these types of wetlands varies in geographic distribution, duration of saturation, vegetation community, and overall ecosystem function. All three types of wetlands provide rich habitat for plant and animal species, delay and store seasonal floodwaters, minimize downstream erosion, and improve water quality.[12]

Climate and meteorology

During the fall, winter, and spring, precipitation in the Sierra ranges from 20 to 80 in (510 to 2,000 mm) where it occurs mostly as snow above 6,000 ft (1,800 m). Rain on snow is common. Summers are dry with low humidity, however afternoon thunderstorms are not uncommon. Summer temperature averages 42 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit (5.5 to 15.5 degrees Celsius). The growing season lasts 20 to 230 days, strongly dependent on elevation.[13]

A unique peculiarity of the Sierra Nevada is that, under certain wind conditions, a large round tube of air begins to roll on the southeast side. This is known as the "Sierra Nevada Rotor" or a "Sierra Wave."[14] This "mountain wave" forms when dry continental winds from the east cause the formation of a stacked set of counter-revolving cylinders of air reaching into the stratosphere. As of 2004, no sailplane has found its top. Similar features occur on many mountain ranges, but it is often observed and utilized in the Sierra. The phenomenon was the subject of an Air Force-funded study in the early 1950s called the Sierra Wave Project.[15] Many recent world altitude records set in unpowered aircraft were set in the Sierra Nevada Wave, most flown from Mojave Airport.

The Sierra Nevada casts the valleys east of the Sierra in a rain shadow, which makes Death Valley and Owens Valley "the land of little rain."[16]

History

Archaeological evidence suggests that petroglyphs found in the region of the Sierra Nevada were created by people of the Martis Complex. Inhabiting the area from 3000 B.C.E. to 500 C.E., the Martis spent their summers at higher elevations and their winters in the lower elevations, reoccupying winter villages and base camps over long periods of time.

The Martis disappeared some 1,500 years ago. Some archaeologists believe that they concentrated their population to the eastern end of their earlier territory, and became the ancestors of the Washo Indians. Others believe they became the ancestors of the Maidu, Washo and Miwok Indians.[17]

By the time of non-Native exploration, the inhabitants of the Sierra Nevada were the Paiute tribe on the east side and the Mono and Sierra Miwok tribe on the western side. Today, passes such as Duck Pass are littered with discarded obsidian arrowheads that date back to trade between tribes. There is also evidence of territorial disputes between the Paiute and Sierra Miwok tribes[18]

History of exploration

European-American exploration of the mountain range began in the 1840s. In the winter of 1844, Lieutenant John C. Fremont, accompanied by Kit Carson, was the first white man to see Lake Tahoe.

By 1860, even though the California Gold Rush populated the flanks of the Sierra Nevada, most of the Sierra remained unexplored. Therefore, the state legislature authorized the California Geological Survey to officially explore the Sierra (and survey the rest of the state). Josiah Whitney was appointed to head the survey.

Men of the survey, including William H. Brewer, Charles F. Hoffmann, and Clarence King, explored the backcountry of what would become Yosemite National Park in 1863.[19] In 1864, they explored the area around Kings Canyon. King later recounted his adventures over the Kings-Kern divide in his book Mountaineering in the Sierra Nevada. In 1871, King mistakenly thought that Mount Langley was the highest peak in the Sierra and climbed it. However, before he could climb the true highest peak (Mount Whitney), fishermen from Lone Pine ascended it.

Between 1892 and 1897, Theodore Solomons was the first explorer to attempt to map a route along the crest of the Sierra. On his 1894 expedition, he took along Leigh Bierce, son of writer Ambrose Bierce.

Other noted early mountaineers included:[19]

- John Muir

- Bolton Coit Brown

- Joseph N. LeConte

- James S. Hutchinson

- Norman Clyde

- Walter Starr, Sr.

- Walter A. Starr, Jr.

Features in the Sierra are named after these men.

Etymology

In 1542, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo, sighting the Santa Cruz Mountains while off the peninsula of San Francisco, gave them the name Sierra Nevada meaning "snowy mountain range" in Spanish. As more specific names were given to California's coastal ranges, the name was used in a general way to designate less familiar ranges towards the interior.[20] In April of 1776 Padre Pedro Font on the second de Anza expedition, looking northeast across the Tulare Lake, described the mountains seen beyond:

Looking northeast we saw an immense plain without any trees, through which the water extends for a long distance, having in it several little islands of lowland. And finally, on the other side of the immense plain, and at a distance of about forty leagues, we saw a great Sierra Nevada whose trend appeared to me to be from south-southeast to north-northwest.[21]

Its most common nickname is the Range of Light. This nickname comes from John Muir,[22] which is a description of the unusually light-colored granite exposed by glacial action.

Protected status

In much of the Sierra Nevada, development is restricted or highly regulated. A complex system of National Forests, National Parks, Wilderness Areas and Zoological Areas designates permitted land uses within the 400-mile (640 km) stretch of the Sierra. These areas are jointly administered by the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, and the National Park Service. There are also 32 state parks.

National Parks and Monuments within the Sierra Nevada include Yosemite National Park, Kings Canyon National Park, Sequoia National Park, Giant Sequoia National Monument, and Devils Postpile National Monument.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 U.S. Forest Service, Ecological Subregions of California: Sierra Nevada. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ National Park Service, The Great Basin. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 U.S. Geological Survey, Facts about Lake Tahoe. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ National Geodetic Survey, Current Survey Control GT1811. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ National Park Service, The General Sherman Tree. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Google Earth images.

- ↑ California State map, 2007.

- ↑ Jeffrey P. Schaffer, Evolution of the Yosemite Landscape—The Nevadan Orogeny, GORP. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Allan A. Schoenherr, A Natural History of California (University of California Press, 1992, ISBN 0-520-06922-6).

- ↑ Joel Michaelsen, Geologic History of California, UC Santa Barbara Department of Geography. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ National Park Service, Vegetation Overview. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 National Park Service, Vegetation—Wetlands. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ US Forest Service, Ecological Subregions of the US: Sierran Steppe—Mixed Forest—Coniferous Forest. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Beth Pratt, The Sierra Wave, Yosemite Association, Nature Notes. Retrieved December 12, 2008. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Bertha Ryan, A Brief History of Soaring at Inyokern Airport, Inyokern Airport Album. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Mary Austin, The Land of Little Rain (University of New Mexico Press, 1974, ISBN 0826303587).

- ↑ Bill Drake, Ancient Petroglyph Makers of the Northern Sierra, Friends of Sierra Rock Art. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Charles Frederick Hoffmann, "Notes on Hetch-Hetchy Valley," Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (San Francisco: CAS, 1868), series 1, 3:5, pp. 368-370. Digitized by Dan Anderson, July 2005. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Roper (1997).

- ↑ Francis P. Farquhar, Exploration of the Sierra Nevada, California Historical Society Quarterly. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ↑ Center for Advanced Technology in Education, University of Oregon, April 2, 1776, Expanded Diary of Pedro Font.

- ↑ John Muir, Mountains of California, Sierra Club. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hill, Mary. 2006. Geology of the Sierra Nevada. California natural history guides, 80. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23696-3.

- Jameson, E. W., Hans J. Peeters, and E. W. Jameson. 2004. Mammals of California. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23582-7.

- Roper, Steve. 1997. Sierra High Route: Traversing Timberline Country. The Mountaineers Press. ISBN 0-89886-506-9.

- Smith, Genny, Diana F. Tomback, and Flora Pomeroy Smith. 2003. Sierra East: Edge of the Great Basin. California natural history guides, 60. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23914-8.

- Storer, Tracy Irwin, Robert L. Usinger, and David Lukas. 2004. Sierra Nevada Natural History. California natural history guides, 73. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24096-0.

- SummitPost.org. Sierra Nevada. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- Weeden, Norman. 1996. A Sierra Nevada Flora. Berkeley, CA: Wilderness Press. ISBN 0-899-97204-7.

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.