Jesuit China missions

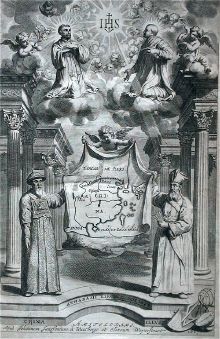

The history of the missions of the Jesuits in China in the early modern era stands as one of the notable events in the early history of relations between China and the Western world, as well as a prominent example of relations between two cultures and belief systems in the pre-modern age. The missionary efforts and other work of the Society of Jesus, or Jesuits between the sixteenth century and seventeenth century played a significant role in introducing Western knowledge, science, and culture to China. Their work laid much of the foundation for much of Christian culture in Chinese society today. Members of the Jesuit delegation to China were perhaps the most influential Christian missionaries in that country between the earliest period of the religion up until the nineteenth century, when significant numbers of Catholic and Protestant missions developed.

The first attempt by Jesuits to reach China was made in 1552 by Saint Francis Xavier, Spanish priest and missionary and founding member of the Society. Xavier, however, died the same year on the Chinese island of Shangchuan, without having reached the mainland. Three decades later, in 1582, led by several figures including the prominent Italian Matteo Ricci, Jesuits once again initiated mission work in China, ultimately introducing Western science, mathematics, astronomy, and visual arts to the imperial court, and carrying on significant inter-cultural and philosophical dialogue with Chinese scholars, particularly representatives of Confucianism. At the time of their peak influence, in the eighteenth-nineteenth centuries, members of the Jesuit delegation were considered some of the emperor's most valued and trusted advisors, holding numerous prestigious posts in the imperial government. Many Chinese, including notable former Confucian scholars, adopted Christianity and became priests and members of the Society of Jesus.

Between the eighteenth century and mid-nineteenth century, nearly all Western missionaries in China were forced to conduct their teaching and other activities covertly. Many Jesuit priests, both Western-born and Chinese, are buried in the cemetery located in what is now the School of the Beijing Municipal Committee.[1] [2]

The Jesuits in China in the sixteenth century

Very little was known about China by the Europeans during the ancient times and the Middle Ages despite some commercial exchange between China under the Han dynasty and the Roman Empire and the presence of Christian communities in China. It is especially puzzling how there was a Nestorian activity as early as 635 C.E. or even before with the proof of a monument erected in 781 C.E. during the Tang dynasty when China was essentially Buddhist. People belonging to the Assyrian church of the East who introduced Christianity were more traders than missionaries who settled near the silk road. However an interesting fact is that foreign Nestorians and Chinese cooperated for the translation into Chinese and that in 638 was published a book called Jesus the Messiah. The Chinese emperor even declared that there was nothing subversive to the Chinese traditions and allowed that the Gospel be preached in China.

Coming from Europe by ship was an extraordinary adventure during which many Christian missionaries lost their lives due to ship wreckage, sickness and attacks by pirates. It would be interesting to compare these adventures with those of Chinese like Xuanzang (602-664) who in the time of the Tang dynasty traveled to India to get the Buddhist scriptures. However there was no journey of Asians in early times for the quest of the origins of Christianity.

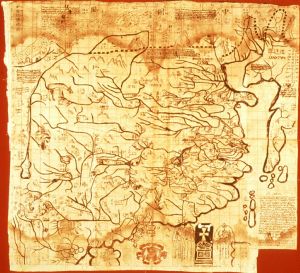

Several adventurers traveled to China or Cathay as it was said but the most famous ones were Niccolò Polo and his son Marco who went to China in 1271 and stayed 17 years because the emperor of the new Mongol dynasty Kublai Khan liked them. Marco Polo became famous by writing Il Milione in 1298 known as The Travels of Marco Polo, which made known China to the Europeans and inspired Christopher Columbus. Marco Polo is supposed to have brought back a map that became a model for Fra Mauro to draw his world map in 1453. Cartography was then reflecting the discovery of the time as today we explored the universe. The Jesuits excelled in improving cartography during their stay in China.

The Jesuits were men whose vision, they were possessed by a dream - the creation of a Sino-Christian civilization that would match the Roman-Christian civilization of the West. The Jesuits have been often misunderstood in their grand projects ad majorem Dei Gloriam. Unfortunately some people even became jealous of their intelligence and successes and the mission in China is one famous example with the Jesuit reductions in South America.

At the end of the sixteenth century already a commercial war existed between the Portuguese holding Goa and Malacca and the Spanish holding Manila. The seas were not safe with many Japanese pirates. Therefore in order to achieve their dreams the Jesuits had to go through many tests. One of the first pioneers in the Chinese port city Canton was the Jesuit Francisco Peres in 1565. Franciscans, then Jesuits, got permission to reside in Macao in 1578. Several religious orders got involved in the missions of China and later in the seventeenth century it created major problems as the cultural approach of Matteo Ricci was not shared by some of them.

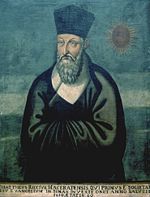

The most famous Jesuit missionary was of course Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) but his work had been prepared by two great Jesuits, Francis Xavier (1506-1552) and Alessandro Valignano. Xavier was one of the founders of the Jesuit order with Saint Ignatius of Loyola and was an extraordinary adventurer in India in 1543, in Indonesia (1546), Malacca (1547), India (1548), Japan (1549) then again India and Malacca. He determined to enter China but died in 1552 on the island of Shangchuan. In a letter that he wrote to Ignatius before dying he said: ‚ÄúChina is an extremely big country where people are very intelligent and who has many scholars‚Ķ/‚Ķ The Chinese are so dedicated to knowledge that the most educated is the most noble.‚ÄĚ [3] Alessandro Valignano made the connection between Francis Xavier and Matteo Ricci.

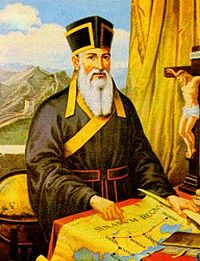

It is important in order to understand Matteo Ricci’s work in China to see the education he received in his native Italy. Commentators remarked that Ricci was a man of the European Renaissance. He in fact combined the Greco-Roman humanities rediscovered at that time and the Catholic spirituality, his culture being extremely vast. He joined the Jesuits when he was 18 and studied in the Roman college where he had two important masters, the German mathematician Christopher Clavius, mathematician and astronomer author of the Gregorian calendar accepted in 1582 and the Italian theologian Robert Bellarmine (1542-1621) who favored a tolerant Christianity. Having become an excellent mathematician Ricci quickly volunteered to go to China but he first had to spend three years in India from 1578 to 1583 before joining his colleague Michele Ruggieri (1543-1607) in Macao in August 1582. When Ricci arrived in Macao, Ruggieri was tired and despaired with the difficulty of the language and with the refusal of the Chinese authorities to allow him to enter the land.

Immediately Ricci studied the language and collected a lot of informations on China writing a "Description of China" in 1582 for Valignano who was in Japan. After numerous difficulties Ruggieri and Ricci entered China on September 10, 1583 at the invitation of the governor of Shiu-hing in the province of Kuan-tung. The great adventure of encounter East-West was starting with high expectations mainly due to the imposing stature of Matteo Ricci.

On one hand Ricci was bringing with him for the Chinese his knowledge in the sciences of Mathematics, Mechanics and Astronomy and the humanities like Philosophy, Literature and poetry. On another hand he quickly mastered the Chinese language, but what was unusual for the period, he absorbed all the Chinese classics and Confucian documents to the point that he was able to converse with the most educated scholars of China. He quickly forced the admiration of the Chinese not just for his intelligence and his memory‚ÄĒbeing able to remember a Chinese text after reading it only once‚ÄĒbut also for his noble character and his deep sense of morality and friendship.

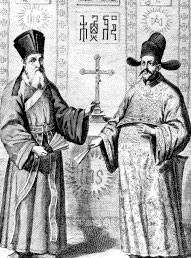

Until 1595 Ricci followed Ruggieri in wearing the robe of Buddhist monks but then decided to identify with the Confucian literati because he never appreciated Buddhism and Daoism, even refusing to study the scriptures. He had perceived the potential of the Chinese classics, seeing in them a resonance with Christian conceptions, and easily made friends with Confucians. The more he conversed with them, however, the more aware he became of the need for a special type of missionary to implement his approach. Furthermore, he saw that this would require a special dispensation from the pope. This was granted. Ricci then wrote to the Jesuit houses in Europe and called for priests - men who would not only be‚Äúgood,‚ÄĚbut also ‚Äúmen of talent, since we are dealing here with a people both intelligent and learned‚ÄĚ [4].

A few responded, and Ricci began to train them so that they might approach the Chinese authorities, offering the court scholarly and scientific assistance with the deliberate intention of making a Confucian adaptation of their style of life, patterns of thought, preaching and worship.They were determined to completely dewesternize themselves. Both Ricci and Ruggieri felt that it would be possible to ‚Äúprove that the Christian doctrines were already laid down in the classical works of the Chinese people, albeit in disguise.‚ÄĚ Indeed, they and their followers were convinced that ‚Äúthe day would come when with one accord all missionaries in China would look in the ancient texts for traces of primal revelation.‚ÄĚ[5]

But tension developed between Ricci and his followers and those of Ruggieri. This was inevitable, since both were exploring different segments of the Chinese intellectual tradition. Ricci's thoroughgoing adaptation to Confucianism and his radical rejection of Daoism could not but conflict with Ruggieri's thesis that there was a closer affinity between the Dao of Chinese thought and the incarnate Logos of the New Testament.

Actually, in their deliberate and arduous efforts to restate the Christian gospel in Chinese thought-forms, they were not innovators. They were merely adopting the same approach toward Chinese thought that the early church fathers had adopted toward Greek Philosophy. Their objective was to identify all the elements of truth which the Chinese literary heritage had contained, to supplement them with the insights of the Western understanding of the natural order, and then to introduce what they saw as the wholly distinctive truths of the Christian gospel.

The Lasting contribution of Matteo Ricci

The lasting success of Ricci in China may be due to some of his personal initiatives in a new cultural approach. He did not attempt like many other missionaries to force conversions. He studied deeply the culture of the other, arose the interest of his guests either humble or high people by offering gifts like clocks, musical instruments or precious clothes from Europe. He concentrated on friendship and discussed ideas. Then often the curiosity made his guests wanting to know more about Europe and Christianity.

Ricci really built a bridge between the Chinese and the Europeans. He introduced the Elements of geometry of Euclides‚ÄĒthat his friend Xu Guangqi translated in Chinese‚ÄĒ, the knowledge of European astronomy and the science of the calender. He made remarkable maps of the world and of China that fascinated the Chinese. On the reverse he translated the Chinese classics for the European readers.

Although Ricci was concerned by evangelization he remained humble and discreet and was far from a colonial attitude that some reproached him in the twenbtieth century. This is visible for example in his missionary directives:

The work of evangelization, of making Christians, should be carried on both in Peking and in the provinces … following the methods of pacific penetration and cultural adaptation. Europeanism is to be shunned. Contact with Europeans, specifically with the Portuguese in Macao, should be reduced to a minimum. Strive to make good Christians rather than multitudes of indifferent Christians … Eventually when we have a goodly number of Christians, then perhaps it would not be impossible to present some memorial to the Emperor asking that the right of Christians to practice their religion be accorded, inasmuch as is not contrary to the laws of China. Our Lord will make known and discover to us little by little the appropriate means for bringing about in this matter His holy will.[2]

Ricci's talent to write

Ricci was able to write on science, philosophy or literature. He wrote on substantial issues with a fine and moving accent that never left the readers indifferent although some criticized that he remained too close to the Medieval world and the thought of Aquinas and was not yet fully a man of the Renaissance. The extraordinary fact is that he is still read in Asia by the most distinguished scholars.

In 1584 Ricci published his famous book in Chinese: Tien Zhu Shi-lu (Ś§©šłĽŚĮ¶ťĆĄ The True Account of God) which was also much read in Korea. In it he discussed the existence and attributes of God, as well as his providence. He explained how a man might know God through the natural law, the Mosaic law, and the Christian law. He wrote of the incarnation of Christ the Word and discussed the sacraments. Through this dialogue between a Chinese scholar and a Western scholar Ricci guides the reader toward his original conscience that is similar in the East and in the West. He said in the introduction:

- One day several friends told me that even If I could not speak perfectly I could not be silent if I saw a thief …/… .

- Therefore I wrote down these dialogues and collected them into a book. A foolish man who thinks that

- What his eyes cannot see does not exist, is like a blind man who does not believe there is a sun in the sky

- because he does not see the sky … . Even if your eyes cannot see it, is the sun not there?

- The truth about the Lord OF HEAVEN is already in the hearts of men. But human beings do not immediately realize this and

- furthermore they are not prone to reflect about such a matter. [6]

- One day several friends told me that even If I could not speak perfectly I could not be silent if I saw a thief …/… .

Ricci is remembered for his capacity of listening to the Chinese and tuning to their culture, making numerous friends. It is no wonder that in 1595 he wrote the famous essay De amicitia, On Friendship. Having been welcome by the duke Kien Ngan the latter expressed that he never failed to invite people of virtue and establish friendship with them and that he was curious to know about friendship in the West. Ricci immediately took his pen to express the best that he knew about friendship. In the introduction he said:

- I, Li Ma-T'eou, came from the Far West to China by ship with a deep respect for the wonderful virtues

- of the Son of Heaven of the Ming and for the instructions given by the former emperors of antiquity.../...

- In the spring of this year I arrived in Nankin after having crossed mountains and rivers. I admired

- the light of China with a secret admiration in thinking that I benefited much from this travel. [7]

- I, Li Ma-T'eou, came from the Far West to China by ship with a deep respect for the wonderful virtues

When Ricci died (1610) more than 2,000 Chinese from all levels of society had confessed their faith in Jesus Christ. Unfortunately, however, Ricci's Jesuits were largely men of their times, firmly convinced that they should also promote Western objectives while planting the Roman Catholic Church in China. As a result, they became involved with the colonial and imperialistic designs of Portugal.

The Jesuits in China in the seventeenth-eighteenth centuries

Ricci achieved his work at the end of the declining Ming dynasty. Only 34 years after he died came to power the Jurchen who created the Qing Dynasty. At first many important Chinese intellectuals resisted this change and even committed suicide. However the new Manchu leaders were able to harmonize their action with the Han Chinese culture and to open China to new ideas coming from the West particularly in terms of sciences.

The foundation that Ricci made gave many fruits for the Jesuit missions in a second glorious moment before a tragic ending. What was needed for a fruitful exchange East-West was the friendship and the confidence, the sharing and the helping in creative projects. The Jesuit successors of Ricci applied what Ricci's wished, combining scientific competence and Christian values.

Scientific achievement

In the seventeenth century two Chinese emperors gave their full confidence and admirations to the Jesuits, living close to them, learning directly from them and even giving them the highest responsibilities such as director of the astronomy observatory or diplomatic missions.

Two Jesuits of that period have been notorious, the German Adam Schall von Bell (1582-1666) and the Belgian Ferdinand Verbiest (1623-1688) excellent mathematicians and astronomers who stimulated the Chinese researches in the scientific fields. The emperor asked Adam Schall to sum up the Western system of astronomy and the science of the calendar, Ch'ung Chen Li Shu. Verbiest was named president of the Mathematics bureau. He reformed the Chinese calendar, made a draft on solar and lunar eclipses, and even worked at the invention of a steam engine for ships.

Before he died Verbiest educated another Belgian Jesuit Antoine Thomas (1644-1709) who gained the same confidence from the emperor. At the request of the emperor Thomas established before Europe the base of the metric system. He also did works of geography establishing a new itinerary between China and Europe. But he was saddened at the end of his life to see the evolution of events.

Philosophical achievement

The Jesuits did not limit their work to science. They were able to explore at the same time the various fields of the humanities. They continued in the 17-18th centuries to translate at the beginning often in Latin difficult classics like the Yijing, the Analects, the Book of Rites…. Although there were various problems due to a projection of Christian ideas on the Chinese texts the Europeans could read for the first time original Chinese philosophical texts.

European readers got enthusiastic, among them the great philosophers of the Enlightenment Leibniz (1646-1716) and Voltaire (1694-1778). Malebranche remained critical of Neo-Confucianism but it was an exception. Louis the XIV asked the French Jesuits to bring back Chinese books. Father Bouvet did bring in 1697 49 books as a gift from the emperor.

It is even difficult to imagine the extraordinary exchange between China and Europe at a time when communications were still so poor. Travels took months; people had to wait for letters, and still Leibniz could correspond with Jesuits in China; he could study the I Ching Book of Changes and get inspiration for his own philosophy, his binary system in Mathematics and his reflection on a world language. It has been said that Chinese Thought has influenced the development of the European enlightenment in preparing the political changes of the American and French Revolutions.

Chinese Rites Controversy

The dynamic work initiated by the Jesuits was a promising beginning if people on both sides had maintained the same friendship and wisdom. However as often in history narrow-mindedness and mistakes were the cause of a tragedy from which East-West relations still suffer.

In the early eighteenth century, a dispute within the Catholic Church arose over whether Chinese folk religion rituals and offerings to the emperor constituted paganism or idolatry. This tension led to what became known as the "Rites Controversy," a bitter struggle that broke out after Ricci's death and lasted for over a hundred years.

At first the focal point of dissension was Ricci's contention that the ceremonial rites of Confucianism and ancestor worship were primarily social and political in nature and could be practiced by converts. The Dominicans charged that they were idolatrous; all acts of respect to the sage and one's ancestors were nothing less than the worship of demons. A Dominican carried the case to Rome, where the controversy dragged on and on, largely because there was no one in the Vatican who knew Chinese culture sufficiently to provide the pope with a ruling. Naturally, the Jesuits appealed to the Chinese emperor, who endorsed Ricci's position. Understandably, he was confused: missionaries attacked missionaries in the Chinese capital. The Chinese reaction was to consider expelling all forgeign Christians.

The timely discovery of the Nestorian monument in 1623 enabled the Jesuits to strengthen their position with the court by meeting an objection the Chinese often expressed - that Christianity was a new religion. They could now point to concrete evidence that a thousand years earlier the Christian gospel had been proclaimed in China; it was not a new but an old faith. The emperor then decided to expel all missionaries who failed to support Ricci's position.

Spanish Inquisition

The Spanish Franciscans, however, did not retreat without further struggle. This was the age of inquisition, when the charge of heresy meant the dungeon and the sword. Eventually they persuaded Pope Clement XI that the Jesuits were making dangerous accommodations to Chinese sensibilities. In 1704 they proscribed against the ancient use of the words Shang Di (supreme emperor) and Tien (heaven) for God. Naturally the Jesuits appealed this decision.

The controversy raged on. In 1742 Pope Benedict XIV officially opposed the Jesuits, forbade all worship of ancestors, and terminated further discussion of the issue. This decree was repealed in 1938. But the methodology of Matteo Ricci remained suspect until 1958, when Pope John XXIII, by decree in his encyclical Princeps Pastorum, proposed that Ricci become ‚Äúthe model of missionaries.‚ÄĚ

In the intervening years the Ming Dynasty collapsed (1644), to be replaced by the ‚Äúnon-scholarly‚ÄĚ and foreign Manchus. The influence of various Catholic missionary orders began to wane. Pope Clement XIV dissolved the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in 1733. The withdrawal from China of this dynamic segment of the missionary force exposed the church to successive waves of persecution. Although many Chinese Christians were put to death and the congregation scattered, the church continued to manifest a ‚Äútough inward vitality‚ÄĚ and kept growing. Clark has well summarized:

When all is said and done, one must recognize gladly that the Jesuits made a shining contribution to mission outreach and policy in China. They made no fatal compromises, and where they skirted this in their guarded accommodation to the Chinese reverence for ancestors, their major thrust was both Christian and wise. They succeeded in rendering Christianity at least respectable and even credible to the sophisticated Chinese, no mean accomplishment.[8]

The Jesuits succeeded in planting a Chinese church that has stood the test of time. However, one should not overlook the fact that the Jesuit financial policy grievously aggravated the difficulties of that church. Their missionaries involved themselves in business ventures of various sorts; they became the landlords of income-producing properties, developed the silk industry for Western trade, and organized money-lending operations on a large scale. All these eventually generated misunderstanding and tension between the foreign community and the Chinese people. The Communists held this against them as late as the mid-twentieth century.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Ron Gluckman, China's Grave Memories. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 George H. Dunne, Generation of Giants: the story of the Jesuits in China in the last decades of the Ming dynasty (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press).

- ‚ÜĎ Jean Lacouture, Jesuits: A Multibiography (Harvill Press, 1996, ISBN 978-1860460234).

- ‚ÜĎ Leonard M. Outerbride, The Lost Churches of China (Nashville: Westminster Press, 1952), 85.

- ‚ÜĎ Johannes Beckmann, A Theological Dialogue between the Christian Faith and Chinese Belief (1962), 124-130.

- ‚ÜĎ Matteo Ricci, The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, translated by Douglas Lancashire and Peter Hu Kuo-chen (Institute of Jesuit Sources, Boston College, 2016).

- ‚ÜĎ After the French translation of Father Stanislas Yen, University of Shanghai, 1947.

- ‚ÜĎ Kenneth Scott Latourette, A History of Christian Missions in China (Gorgias Press, 2009).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beckmann, Johannes. A Theological Dialogue between the Christian Faith and Chinese Belief. 1962.

- Brockey, Liam Matthew. Journey to the East: the Jesuit mission to China, 1579-1724. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0674024489

- Dunne, George H. Generation of giants; the story of the Jesuits in China in the last decades of the Ming dynasty. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1962. OCLC 664728

- Lacouture, Jean. Jesuits: A Multibiography. Harvill Press, 1996. in English. ISBN 978-1860460234

- Lancashire, Douglas, and Peter Hu Kuo-chen (trans.). The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven. Taiwan: The Ricci Institute, 1985.

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. A History of Christian Missions in China. Gorgias Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1593337865

- Outerbridge, Lawrence M. Lost Churches of China. Nashville: Westminster Press, 1952. ASIN B0007DUH80

- Ricci, Matteo. The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven, translated by Douglas Lancashire and Peter Hu Kuo-chen. Institute of Jesuit Sources, Boston College, 2016.

- Rowbotham, Arnold H. Missionary and mandarin; the Jesuits at the court of China. New York: Russell & Russell, 1966. OCLC 545104

- Spence, Jonathan D. The memory palace of Matteo Ricci. New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 1984. ISBN 978-0670468300

- Tremblay, Mark Alan. Jesuit scientist-missionaries in China: the Jesuit use of European science as a means of propagating the faith. Thesis (A.B., Honors in History and Science)‚ÄĒHarvard University, 1994. OCLC 31070504

External links

All links retrieved January 2, 2025.

- China's Grave Memories by journalist Ron Gluckman.

- Vatican: Jesuits in China.

- Vatican: How Rome went to China.

- St. Ignatius Loyola New Advent.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.