Christian symbolism

| Part of a series of articles on Christianity | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Foundations Bible Christian theology History and traditions

Topics in Christianity Important figures | ||||||

Christian symbolism is defined as the investing of outward things or actions with an inner meaning the expression of Christian ideas. In a greater or less degree symbolism is essential, to every kind of external worship. Christianity has borrowed, without hesitation, from the common stock of significant symbols known to all periods and to all regions of the world. Religious symbolism is effective precisely in the measure in which it is sufficiently natural and simple to appeal to the intelligence of the people. The choice of suitable acts and objects for this symbolism is not so wide that it would be easy to avoid the appearance of an imitation of other traditions even if there had been a deliberate attempt invent an entirely new ritual.[1]

The symbol of the Cross has been revered by Christians but controversial in Jewish and Muslim communities, as Jews were blamed for the crucifixion and the Crusaders fought under the symbol of the cross.

Symbols drawn from pre-Christian traditions

Common in most Christian religious symbolism are emblems, figures or ideas drawn from the cultures which fostered the origin of Christianity.[2] These symbols existed in those cultures and have been adopted and imbued with Christian meaning. The phoenix would come to stand for the Resurrection, the Egg represented rebirth. These are but two examples of the incorporation of pagan symbols for use in Christian art and customs.

Many Christian symbols were derived from specific allegories found in the Hebrew scriptures of the Old Testament.[3] Their use in Judaism predated the birth of Christ. Trees appear with symbolic meaning throughout Hebrew tradition. From the tree of knowledge of good and evil, through which the Fall of man and the curse of death came, to the tree of life—to which access has been cut off for mankind—to promises concerning the root of Jesse, the branch, the Messiah, who would be hung on a tree to bear the curse, and would be raised up again for the healing of the nations.[3]

Early Christian symbols

Elemental symbols

Elemental symbols were widely used by the early Christian church. Water has specific symbolic significance for Christians that derived from the ritual purity of Jewish tradition. Baptism, which represented a "new birth" derived from the ritual tradition of water cleansing representing purity. Fire, especially in the form of a candle flame, represents both the Holy Spirit and light. Tongues of fire are used to symbolize the Holy Spirit at Pentecost; Jesus' describes his followers as the light of the world; God is a consuming fire found in Hebrews 12.[3]

Ichthys

Among the symbols employed by the early Christians, that of the fish seems to have ranked first in importance. Ichthus (ΙΧΘΥΣ, Greek for fish) is an acronym, a word formed from the first letters of several words. It compiles to "Jesus Christ God's Son Saviour," in ancient Greek "Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ"

- Iota is the first letter of Iesous (Ἰησοῦς), Greek for Jesus.

- Chi is the first letter of Christos (Χριστóς), Greek for "anointed."

- Theta is the first letter of Theou (Θεοῦ), that means "God's," genitive case of Θεóς "God."

- Upsilon is the first letter of Huios (Υἱός), Greek for Son.

- Sigma is the first letter of Soter (Σωτήρ), Greek for Savior.

Origin

From monumental sources such as tombs we know that the symbolic fish was familiar to Christians from the earliest times. It can be seen in such Roman monuments as the Capella Greca and the Sacrament Chapels of the catacomb of Saint Callistus. The use of the Ichthys symbol by early Christians appears to date from the end of the first century C.E. to the first decades of the second century.[4] The symbol itself may have been suggested by the miraculous multiplication of the loaves and fishes or the repast of the seven Disciples, after the Resurrection, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee.[5]

Use

Societies of Christians in Hellenistic Greece and Roman Greece, prior to the Edict of Milan, protected their congregations by keeping their meetings secret. In order to point the way to ever-changing meeting places, they developed a symbol which adherents would readily recognize, and which they could scratch on rocks, walls and the like, in advance of a meeting. At the time, a similar symbol was used by Greeks to mark the location of a funeral, so using the ichthys also gave an apparent legitimate reason for Christians to gather.

…when a Christian met a stranger in the road, the Christian sometimes drew one arc of the simple fish outline in the dirt. If the stranger drew the other arc, both believers knew they were in good company. Current bumper-sticker and business-card uses of the fish hearken back to this practice. The symbol is still used today to show that the bearer is a practicing Christian.[6]

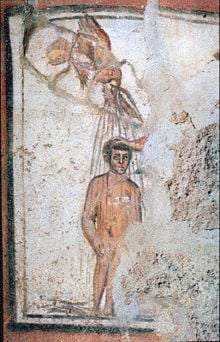

Tomb paintings

Christians from the very beginning adorned their catacombs with paintings of Christ, of the saints, of scenes from the Bible and allegorical groups. The catacombs are the cradle of all Christian art. The first Christians had no prejudice against images, pictures, or statues. That idea has been dispelled by Christian archaeology. The idea that they must have feared the danger of idolatry among their new converts is disproved in the simplest way by the pictures even statues, that remain from the first centuries.[7] Early Christians accepted the art of their time and used it, as well as a poor and persecuted community could, to express their religious ideas. From the second half of the first century to the time of Constantine the Great they buried their dead and celebrated their rites in these underground chambers. The Christian tombs were ornamented with indifferent or symbolic designs—palms, peacocks, with the chi-rho monogram, with bas-reliefs of Christ as the Good Shepherd, or seated between figures of saints, and sometimes with elaborate scenes from the New Testament.[7] Other Christian symbols include the dove (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (symbolic of Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolising the necessary connectedness of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from the writings found the New Testament.[3]Other decorations that were common included garlands, ribands, stars landscapes, which had symbolic meanings, as well.[7]

Cross and crucifix

The cross, which is today one of the most widely recognized symbols in the world, was used as a symbol from the earliest times. This is indicated in the anti-Christian arguments cited in the Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapters IX and XXIX, written at the end of that century or the beginning of the next,[8][9] and by the fact that by the early third century the cross had become so closely associated with Christ that Clement of Alexandria, who died between 211 and 216, could without fear of ambiguity use the phrase τὸ κυριακὸν σημεῖον (the Lord's sign) to mean the cross, when he repeated the idea, current as early as the Epistle of Barnabas, that the number 318 (in Greek numerals, ΤΙΗ) in Genesis 14:14 was a foreshadowing (a "type") of the cross (T, an upright with crossbar, standing for 300) and of Jesus (ΙΗ, the first two letter of his name ΙΗΣΟΥΣ, standing for 18),[10] and his contemporary Tertullian could designate the body of Christian believers as crucis religiosi, i.e. "devotees of the Cross".[11] In his book De Corona, written in 204, Tertullian tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace repeatedly on their foreheads the sign of the cross.[12]

The Jewish Encyclopedia states:

The cross as a Christian symbol or "seal" came into use at least as early as the second century (see "Apost. Const." iii. 17; Epistle of Barnabas, xi.-xii.; Justin, "Apologia," i. 55-60; "Dial. cum Tryph." 85-97); and the marking of a cross upon the forehead and the chest was regarded as a talisman against the powers of demons (Tertullian, "De Corona," iii.; Cyprian, "Testimonies," xi. 21-22; Lactantius, "Divinæ Institutiones," iv. 27, and elsewhere). Accordingly the Christian Fathers had to defend themselves, as early as the second century, against the charge of being worshipers of the cross, as may be learned from Tertullian, "Apologia," xii., xvii., and Minucius Felix, "Octavius," xxix. Christians used to swear by the power of the cross.[13][14]

Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix, did not appear in use until the fifth century.[3]

Peacock

Ancient people believed that the flesh of peafowl did not decay after death, and it so became an immortality symbol. This symbolism was adopted by early Christianity, and thus many early Christian paintings and mosaics show the peacock. The peacock is still used in the Easter season especially in the East.[15]

Symbols of Christian Churches

Sacraments

Some of the oldest symbols in the Christian church are the sacraments, the number of which vary between denominations. Always included are Eucharist and baptism. The others which may or may not be included are ordination, unction, confirmation, penance and marriage. They are together commonly described as an outward and visible sign of an inward and spiritual grace or, as in the Roman Catholic system, "outward signs and media of grace."[16] At the very least, the rite is seen as a symbol of the spiritual change or event that takes place. In the Eucharist, the bread and wine are, at the least, symbolic of the broken body and shed blood of Jesus, and in Roman Catholicism, believed to be the actual Body and Blood of Jesus which in turn are representative of the death of Jesus which brings salvation to the recipient. The rite of baptism is, at the least, symbolic of the cleansing of the sinner by God, and, especially where baptism is by immersion, of the spiritual death and resurrection of the baptized person. Opinion differs as to the symbolic nature of the sacraments, with some Protestant denominations considering them entirely symbolic, and Roman Catholics, Orthodox, some Anglicans, and some Lutherans believing that the outward rites truly do, by the power of God, act as media of grace.[16]

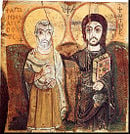

Icons

The tomb paintings of the early Christians led to the development of icons. An icon is an image, picture, or representation; it is likeness that has symbolic meaning for an object by signifying or representing it, or by analogy, as in semiotics. The use of icons, however, was never without opposition. It was recorded that, "there is no century between the fourth and the eighth in which there is not some evidence of opposition to images even within the Church.[17] Nonetheless, popular favor for icons guaranteed their continued existence, while no systematic apologia for or against icons, or doctrinal authorization or condemnation of icons yet existed.

Though significant in the history of religious doctrine, the Byzantine controversy over images is not seen as of primary importance in Byzantine history. "Few historians still hold it to have been the greatest issue of the period… "[18]

The Iconoclastic Period began when images were banned by Emperor Leo III the Isaurian sometime between 726 and 730. Under his son Constantine V, a council forbidding image veneration was held at Hieria[19] near Constantinople in 754. Image veneration was later reinstated by the Empress Regent Irene, under whom another council was held reversing the decisions of the previous iconoclast council and taking its title as Seventh Ecumenical Council. The council anathemized all who hold to iconoclasm, i.e. those who held that veneration of images constitutes idolatry. Then the ban was enforced again by Leo V in 815. And finally icon veneration was decisively restored by Empress Regent Theodora.

Today icons are used particularly among Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Coptic and Eastern Catholic Churches.

Examples of other symbols

- Alpha and omega

- Anchor

- Apple

- Bestiaries

- Borromean rings

- Burning Bush

- Candles

- Christian flag

- Cross and Crown

- IHS (monogram)

- INRI

- Lamb

- Mitre

- Pentagram

- Pelican

- Rose Cross

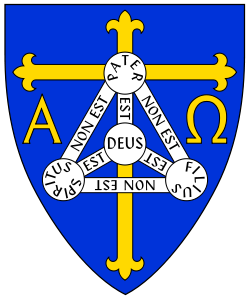

- Shield of the Trinity (or Scutum Fidei)

- Vesica Piscis

Notes

All links Retrieved July 20, 2008.

- ↑ Herbert Thurston, "Symbolism" Catholic Encyclopedia (Robert Appleton Company, 1912) [1]. accessdate 2008-07-20

- ↑ Bill Moyers, and Joseph Campbell. The Power of Myth, Betty Sue Flowers, (ed.) (New York: Doubleday, 1988. ISBN 0385247737)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Maurice Dilasser. The Symbols of the Church. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1999 ISBN 081462538x)

- ↑ Maurice Hassett, "Symbolism of the Fish" Catholic Encyclopedia 1912 [2]. accessdate 2008-07-20

- ↑ John 21:9

- ↑ Elesha Coffman, "Ask the Editors" Christianity Today, October 26, 2001. What is the origin of the Christian fish symbol?.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Adrian Fortescue, "Veneration of Images" Catholic Encyclopedia 1912. [3]. accessdate 2008-07-20

- ↑ ANF04. Fathers of the Third Century: Tertullian, Part Fourth; Minucius Felix; Commodian; Origen, Parts First and Second. Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

- ↑ Minucius Felix speaks of the cross of Jesus in its familiar form, likening it to objects with a crossbeam or to a man with arms outstretched in prayer (Octavius of Minucius Felix, chapter XXIX).

- ↑ Stromata, book VI, chapter XI.earlychristianwritings.

- ↑ Apology, chapter xvi. In this chapter and elsewhere in the same book, Tertullian clearly distinguishes between a cross and a stake.

- ↑ "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign" (De Corona, chapter 3)

- ↑ see Apocalypse of Mary, viii., in James, "Texts and Studies," iii. 118

- ↑ JewishEncyclopedia.com - CROSS:

- ↑ Peter and Linda Murray, "Birds, symbolic." Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art. (2004).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 D.J. Kennedy, "Sacraments" Catholic Encyclopedia 1912. [4].accessdate 2008-07-20

- ↑ Ernst Kitzinger. The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm. (Dumbarton Oaks, 1954), quoted by Jaroslav Pelikan. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600-1700. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.)

- ↑ Patricia Karlin-Hayter. Oxford History of Byzantium. (Oxford University Press, 2002.)

- ↑ See Council of Hieria.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dilasser, Maurice. The Symbols of the Church. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1999. ISBN 081462538x

- Karlin-Hayter, Patricia. Oxford History of Byzantium. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780198140986

- Kitzinger, Ernst. The Cult of Images in the Age before Iconoclasm. Dumbarton Oaks, 1954, quoted by Jaroslav Pelikan, in The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600-1700. University of Chicago Press, 1974. ISSN 0070-7546

- Moyers, Bill and Joseph Campbell. The Power of Myth. ed. Betty Sue Flowers, New York: Doubleday, 1988. ISBN 0385247737

- Murray, Peter and Linda. "Birds, symbolic." Oxford Dictionary of Christian Art. 2004. ISBN 0198609663

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. The Spirit of Eastern Christendom 600-1700. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Christian Symbols and Glossary (keyword searchable, includes symbols of saints)

- Color Symbolism in The Bible An in depth study on symbolic color occurrence in The Bible.

- Old Christian Symbols from book by Rudolf Koch

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.