Artemis

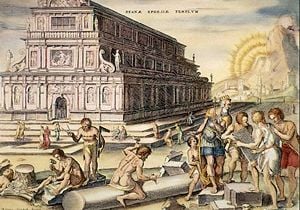

In Greek mythology, Artemis (Greek: Ἄρτεμις or Ἀρτέμιδος) was the daughter of Zeus and Leto and the twin sister of Apollo. She was usually depicted as the maiden goddess of the hunt, bearing a bow and arrows. Later she became associated with the Moon and both deer and cypress are sacred to her. She was seen to be the patron of women (in general) and childbirth (in specific), both of which helped to ensure her continued mythical and religious viability. Indeed, she was one of the most widely venerated of the Greek deities and manifestly one of the oldest deities in the Olympian pantheon.[1] The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (located in western part of Turkey) was one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

In later times, Artemis was associated and considered synonymous with the Roman goddess Diana. In Etruscan mythology, she took the form of Artume.

Name, Characterization and Etymology

Artemis, the virginal goddess of nature and hunting, was a ubiquitous presence in both the mythic tales and the religious observances of the ancient Greeks. Despite this, her provenance seems foreign, as attested to by the fact that no convincing Greek etymology exists for her name.[2] Her character is elegantly summarized in the Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite, which states:

Nor does laughter-loving Aphrodite ever tame in love Artemis, the huntress with shafts of gold; for she loves archery and the slaying of wild beasts in the mountains, the lyre also and dancing and thrilling cries and shady woods and the cities of upright men.[3]

Epithets

Artemis was known by various names throughout the Hellenic world, likely because her cult was a syncretic one that blended various deities and observances into a single united form.

Some of these epithets include:

- Agrotera - goddess of hunters

- Amarynthia - from a festival in her honor originally held at Amarynthus in Euboea

- Aphaea - an Athenian cultic form (related to the island of Aegina)

- Cynthia - another geographical reference, this time to her birthplace on Mount Cynthus on Delos

- Kourotrophos - the nurse of youths

- Limnaia - her name in the Acadian cult

- Locheia - goddess of childbirth and midwives

- Orthia - the name associated with her cult in Sparta

- Parthenia - "the maiden"

- Phoebe - the feminine form of her brother Apollo's epithet Phoebus

- Potnia Theron - the patron of wild animals[4][5]

Mythic Accounts

Birth

After one of Zeus's many extra-marital dalliances, Leto (a Titaness) finds herself pregnant with his divine offspring. Unfortunately for her, news of this predicament was borne to Hera (Zeus' justifiably jealous wife), who vengefully declared that the ailing mistress was barred from giving birth on terra firma (or, in another version, anywhere that the sun shone)[6] and ordered one of her handmaidens to ensure that Leto abided by this cruel decree. Already straining in her labor, the troubled maid chanced to find the rocky island of Delos, which happened not to be anchored to the mainland. As it provided a loophole to Hera's vindictive curse, it was there that the Titaness gave birth to her twins.[7] Intriguingly, some early accounts suggest that Artemis was born first and then assisted with the birth of Apollo, or that Artemis was born one day before Apollo on the island of Ortygia, and that she assisted her mother in crossing the sea to Delos the next day to birth her twin.[8] This postulation is notable as both attributions are consistent with the cultic role of the “Divine Huntress” as a helper in childbirth.

In a parallel account, it is suggested that Hera kidnapped Ilithyia (the goddess of childbirth) in order to prevent Leto from going into labor. The other gods, sympathetic to Leto's plight, coaxed Hera into releasing the birthing-goddess by offering her an enormous amber necklace.[9][10]

Childhood

Unlike her twin, whose youthful exploits are depicted in numerous sources, the childhood of Artemis is relatively under-represented (especially in older classical materials). However, one account depicting this period has survived in a poem by Callimachus (c. 305 B.C.E.–240 B.C.E.), who fancifully describes a conversation between the goddess (then "still a little maid") and Zeus, her benevolent pater:

She spake these words to her sire: “Give me to keep my maidenhood, Father, forever: and give me to be of many names, that Phoebus may not vie with me. And give me arrows and a bow [,] ... and give me to gird me in a tunic with embroidered border reaching to the knee, that I may slay wild beasts. And give me sixty daughters of Oceanus for my choir – all nine years old, all maidens yet ungirdled; and give me for handmaidens twenty nymphs of Amnisus who shall tend well my buskins, and, when I shoot no more at lynx or stag, shall tend my swift hounds. And give to me all mountains; and for city, assign me any, even whatsoever thou wilt: for seldom is it that Artemis goes down to the town. On the mountains will I dwell and the cities of men I will visit only when women vexed by the sharp pang of childbirth call me to their aid even in the hour when I was born the Fates ordained that I should be their helper, forasmuch as my mother suffered no pain either when she gave me birth or when she carried me win her womb, but without travail put me from her body.” So spake the child and would have touched her father’s beard, but many a hand did she reach forth in vain, that she might touch it.[11]

Given the etiological character of such a catalog of desires, it is perhaps not surprising that this listing echoes various elements of goddess's mythos (from her sexual abstinence and her association with virginal handmaidens, to her status as a nature deity (or huntress) and her role as a helper in childbirth).

The Spiteful Goddess

In many mythic accounts, Artemis is characterized as an utterly unforgiving and vengeful being, visiting death upon any mortal who offends her. However, it should be noted that many of these seemingly callous executions follow well-established patterns within the overall moral framework presented by the Greek hymns and texts. For instance, the crime of hubris, for which Artemis slays Actaeon and Chione, and grimly punishes Agamemnon and Niobe, was also the motive for Apollo's murder of Marsyas and Athena's contest with (and eventual transformation of) Arachne.

Actaeon

In some versions of the tale, the virgin goddess is bathing in a secluded spring upon Mount Cithaeron, when the Theban hunter Actaeon stumbles upon her. Enraged that a male had seen her nakedness, she transforms him into a stag, who then proceeds to be pursued and torn asunder by his own hounds.[12] In an earlier version of the story, the Theban's offense was caused by a boast that his hunting prowess rivaled the goddess's own.[13] In this version at well, the story culminates with the transformation and death of the unfortunate hunter.

Chione

In a similar manner, Ovid's Metamorphoses describes the death of Chione, a lover of both Hermes and Apollo, who dared to compare her own physical assets to those of Artemis:

But what is the benefit in having produced two sons, in having pleased two gods, in being the child of a powerful father, and grandchild of the shining one? Is glory not harmful also to many? It certainly harmed her! She set herself above Diana [Artemis], and criticized the goddess’s beauty. But, the goddess, moved by violent anger, said to her: “Then I must satisfy you with action.” Without hesitating, she bent her bow, sent an arrow from the string, and pierced the tongue that was at fault, with the shaft. The tongue was silent, neither sound nor attempts at words followed: and as she tried to speak, her life ended in blood.[14]

Iphigenia and the Taurian Artemis

In the months leading up to the Trojan War, Agamemnon managed to offend the Artemis, either by bragging about his own abilities as an archer[15] or by slaying an animal from a sacred grove.[16][17] Regardless of the cause, Artemis decided that she would confound the invading army's efforts to reach Troy by directing the winds against them, and thus rendering their massive fleet useless:

Calchas [a Greek seer] said that they could not sail unless Agamemnon's most beautiful daughter were offered to Artemis as a sacrifice. The goddess was angry with Agamemnon because when he had shot a deer he said that not even Artemis could have done it.... After he heard this prophecy Agamemnon sent Odysseus and Talthybius to Clytemnestra to ask for Iphigenia, saying that he had promised to give her to Achilles to be his wife as a reward for going on the expedition. Clytemnestra sent her, and Agamemnon, placing her beside the altar, was about to slaughter her when Artemis carried her off to Tauris. There she made her a priestess and substituted a deer for her at the altar. Some, however, say that Artemis made her immortal.[18]

While the Apollodorus version quoted above has Artemis relenting at the last minute, other versions (including the Agamemnon of Aeschylus) simply allow the king to slit his daughter's throat upon the sacrificial altar.[19]

Niobe

In another case of deadly hubris, Niobe, a queen of Thebes and wife to King Amphion, boasted that she was superior to Leto because she had 14 children, while Leto had only two. Upon hearing this impious gloating, the twin deities proceeded to murder all of her offspring, with Artemis cutting down her daughters with poisoned arrows and Apollo massacring her sons as they practiced athletics. At the grim sight of his deceased offspring, Amphion went mad and killed himself (or was killed by Apollo). Likewise, the devastated Queen Niobe committed suicide or was turned to stone by Artemis as she wept.[20]

Orion

Orion, another legendary hunter, also bore the brunt of Artemis's rage, though in this case it seems to have been justified. Though the exact cause for the goddess's wrath varies. In some sources, Orion begins a romance with Eos (the goddess of dawn), in others, he attempts to rape one of her handmaidens or even the goddess herself.[21] In a later version, the poet Istros suggests that Artemis actually fell in love with the hunter. This prompted Apollo, who did not want his sister to break her vow of chastity, to trick her into shooting Orion accidentally.[22] In response, Eos is slain by Artemis, who either perforates him with arrows or (more creatively) summons a scorpion[23] that injects him with poison.[24] The latter version provides an etiological explanation for the particular layout of the cosmos, as Orion (now catasterized into a constellation) still attempts to stay as far as possible from Scorpio.

Artemis at Brauron

A final depiction of the goddess's fickle temper is provided by an account of the sacred bear that dwelt near her shrine at Brauron (a rural community near Athens):

<blcokquote>A she-bear once was given to the sanctuary of Artemis and was tamed. Once a maiden was playing with the bear, and the bear scratched out her eyes. The girl's brother(s), in grief for her, killed the bear. And then a famine befell the Athenians. The Athenians inquired at the Oracle of Delphi as to its cause, and Apollo revealed that Artemis was angry at them for the killing of the bear, and as punishment and to appease her every Athenian girl, before marriage, must "play the bear" for Artemis.[25]

While the events of this myth may seem somewhat unremarkable, especially compared to some of the other ruthless acts performed by the goddess, it provides an important backdrop for a common Athenian rite of passage. This ritual, which was actually required of all young Athenian women, is described below.

Other Important Accounts

Callisto

One of the most famed tales featuring Artemis (one that is reproduced in both literature and visual art) is the story of Callisto, the unfortunate daughter of Lycaon, king of Arcadia. This young woman, who served as one of the divine huntress's attendants, was entirely devoted to the goddess and thus found it necessary to take a vow of chastity. Unfortunately for her, she was a desirable and comely young maid, and she caught the eye of the lascivious Zeus. Not wanting his young quarry to flee, the crafty god appeared to her disguised as Artemis, gained her confidence, then took advantage of her.[26] Months later, when Artemis discovered that one of her maidens was pregnant, she was became apoplectic and banished the offender from their company. Further, the long-suffering Callisto was then transformed into a bear, either by Artemis[27] or by Hera, who responds with characteristic ire to her husband's most recent infidelity.[28]

Regardless, the young woman (now in her ursine form) proceeded to give birth to a son, Arcas, who, years later, almost accidentally killed his own mother while hunting. Fortunately, Zeus witnessed this grim scene and intervened in time. Out of pity, the Sky God placed Callisto into the heavens, which explains the origin of the Ursa Major constellation.

Trojan War

Artemis favored the Trojans during their ten-year war with the Greeks. As a result of her patronage, she came to blows with Hera, who was a staunch supporter of the Hellenes. In this conflict, Artemis was shamefully trounced, as Hera struck her on the ears with her own quiver, which caused the arrows to fall out (and rendered her defenseless in the process). As Artemis fled crying to Zeus, Leto gathered up the bow and arrows which had fallen out of the quiver.[29] Noting the impudent depiction of the goddess in this account, Rose comments: "this contrasts so sharply with the respectful treatment accorded to her mother Leto as to suggest that there is more than a trace of odium theologicum behind it; Artemis is a goddess of the conquered race, not yet fully naturalized a Greek, as Hera is."[30]

Cult of Artemis

Artemis, in one of various forms, was worshiped throughout the Hellenic world, in a cult whose geographical expansiveness was only rivaled by its great antiquity. Likewise, her areas of patronage were equally varied: she was the goddess of the hunt and the wild; of chastity; of unexpected mortality (especially of women);[31] of the moon (a position that she gradually usurped from Selene); and of childbirth. Part of this can be explained by the syncretic nature of her cult, which united various (and largely disparate) local observances under her name.[32] The best known of these were located in her birthplace, the island of Delos; in Brauron (outside of Athens); at Mounikhia (located on a hill near the port Piraeus); and in Sparta. In addition to the cultic observances associated with specific temples, the goddess was also celebrated at numerous festivals throughout the empire.[33][34] Further, the range of beliefs associated with Artemis expanded during the Classical period, as she came to be identified with Hecate, Caryatis (Carya) and Ilithyia.

The general character of these worship practices is attested to in a surviving temple inscription credited to Xenophon, which states: "This place is sacred to Artemis. He who owns it and enjoys its produce must offer in sacrifice a tenth each year, and from he remainder must keep the temple in good condition. If someone fails to do these things, the goddess will take care of it." This text implies a particular relationship with the goddess, in that she is credited with the temple patron's material success—worldly fortune that she seems equally able to revoke. The importance of placating Artemis is also attested to in the Athenian festival of Brauronia, a rite of passage where local girls were required to "play the bear" in order to repay the goddess for a past offense. However, these observances were also tied to the overall associations that the goddess had for the Hellenes:

The simples explanation may be that through the rituals of the Arteia ["playing the bear"] these girls, as they approaches puberty and marriage, were being formally initiated into the cult of the goddess who would be of major importance to their lives as women of the future. Artemis is the goddess most invoked by women in casual conversation ("By Artemis,..."), and as Lochia (Of the Child-Bearing Bed) she assisted women in childbirth – a critical new role facing these girls."[35]

In general, virginal Artemis was worshiped as a fertility/childbirth goddess throughout the ancient Greek world, a fact that was explained through the etiological myth that she aided her mother in delivering her twin.

The Lady of Ephesus

In Ionia the "Lady of Ephesus," a goddess that the Hellenes identified with Artemis, was a principal deity. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (located in western part of Turkey), one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, was probably the best known center of her worship apart from Delos. Here the lady whom Greeks associated with Artemis through interpretatio Graecae was worshipped primarily as a mother goddess, akin to the Phrygian goddess Cybele. In this ancient sanctuary, her cult image depicted the goddess adorned with multiple rounded breast-like protuberances on her chest.[36][37][38]

These devotions continued into the Common Era, and are, in fact, attested to in the Christian Gospels. Specifically, when Paul visits the town of Ephasus, the local metalsmiths, who feel threatened by his preaching of a new faith, jealously riot in the goddess's defense, shouting "Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!" (Acts 19:28). The vigor of this crowd was so notable that Paul feared for his life, and fled the town under cover of darkness.[39]

Artemis in art

The oldest representations of Artemis in Greek Archaic art portray her as Potnia Theron ("Queen of the Beasts"): a winged goddess holding a stag and leopard in her hands, or sometimes a leopard and a lion. This winged Artemis lingered in ex-votos as Artemis Orthia, with a sanctuary close by Sparta.[40]

In Greek classical art she is usually portrayed as a maiden huntress clothed in a girl's short skirt,[41] with hunting boots, a quiver, a silver bow and arrows. Often she is shown in the shooting pose, and is accompanied by a hunting dog or stag. Her darker side is revealed in some vase paintings, where she is shown as the death-bringing goddess whose arrows fell young maidens and women, such as the daughters of Niobe.

Only in post-Classical art do we find representations of Artemis-Diana with the crown of the crescent moon, as Luna. In the ancient world, although she was occasionally associated with the moon, she was never portrayed as the moon itself.[42]

Notes

- ↑ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical, trans. John Raffan (Oxford: Blackwell, 1985, ISBN 0631112413), 149.

- ↑ Lewis Richard Farnell, The Cults of the Greek States, vol. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907), 426.

- ↑ "Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite" (16-21) in Hesiod, The Homeric Hymns, and Homerica, ed. and trans. Hugh G. Evelyn-White (Cambridge, MA: Loeb Classical Library, 1914). Available online from the Online Medieval and Classical Library. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ↑ Jessica Amanda Salmonson. The Encyclopedia of Amazons (New York: Paragon House, 1991, ISBN 1557784205), 5.

- ↑ Farnell (vol. 2); see also Theoi.com: “Titles of Artemis” for an extensive listing of every epithet used for the goddess in the surviving mythic corpus. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ↑ H. J. Rose, A Handbook of Greek Mythology (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959, ISBN 0525470417), 114-115. In this version, Leto's birthing place (the island of Delos) is kept from the sun's rays by Poseidon, who agrees to help her for reasons unknown.

- ↑ Timothy Gantz, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993, ISBN 080184410X), 86.

- ↑ H. W. Parke, Festivals of the Athenians (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977, ISBN 0801410541), 146-149.

- ↑ Barry B. Powell, Classical Myth, 2nd ed. (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998, ISBN 0137167148), 167.

- ↑ See also the Homeric Hymn to Apollo: "But Leto was racked nine days and nine nights with pangs beyond wont. And there were with her all the chiefest of the goddesses, Dione and Rhea and Ichnaea and Themis and loud-moaning Amphitrite and the other deathless goddesses save white-armed Hera, who sat in the halls of cloud-gathering Zeus. Only Eilithyia, goddess of sore travail, had not heard of Leto's trouble, for she sat on the top of Olympus beneath golden clouds by white-armed Hera's contriving, who kept her close through envy" (ll. 89-99).

- ↑ Callimachus, "Hymn III: To Artemis" (2-28) in Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams, trans. A. W. Mair and G. R. Mair (London: William Heinemann, 1921). Available online from theoi.com. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses (3.138-239).

- ↑ Powell, 181.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses (11:339). Available online from tkilne.com. Retrieved September 6, 2007.

- ↑ The Kypria, quoted in Gantz, 98.

- ↑ Sophocles, Electra, 566-572.

- ↑ Gantz, 98-99.

- ↑ Apollodorus (11.3.21-22).

- ↑ Powell, 514-515.

- ↑ Apollodoros (3.5.6); Rose, 144.

- ↑ Rose, 115.

- ↑ Quoted in Gantz, 273.

- ↑ In some versions, it is Gaia that sends the creature—usually in response to the hunter's vain boast that he is more powerful than any creature (Gantz, 272).

- ↑ Powell, 180-181; Rose, 115.

- ↑ Jon D. Mikalson, Ancient Greek Religion (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005, ISBN 0631232222), 62.

- ↑ This encounter is definitively characterized as a rape in Ovid (2:417-440).

- ↑ Gantz, 98.

- ↑ Rose, 118.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad (21:470-513).

- ↑ Rose, 113.

- ↑ Gantz provides an impressive catalog of mythic sources to support this non-standard religious role (97).

- ↑ Farnell (vol. 2), 425-428. See also Theoi.com: Artemis for an excellent introduction to four different cults of Artemis that were eventually blended together through myth.

- ↑ See Matthew Dillon, Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece (London and New York: Routledge, 1997, ISBN 0415127750).

- ↑ Parke.

- ↑ Mikalson, 151.

- ↑ Farnell (vol. 2), 480-482.

- ↑ Powell notes that these bulbous forms could also signify bull testes, which would have been a logical offering to a fertility goddess (178).

- ↑ See also Vicki Goldberg, "In Search of Diana of Ephesus," New York Times (August 21, 1994).

- ↑ Powell, 178.

- ↑ See Burkert for a depiction of this form: 154, 172.

- ↑ Homer portrayed Artemis as girlish in the Iliad.

- ↑ Farnell (vol. 2), 456-460, 531.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion: Archaic and Classical. Translated by John Raffan. Oxford: Blackwell, 1985. ISBN 0631112413

- Dillon, Matthew. Pilgrims and Pilgrimage in Ancient Greece. London and New York: Routledge, 1997. ISBN 0415127750

- Farnell, Lewis Richard. The Cults of the Greek States (5 vols.). Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1907.

- Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993. ISBN 080184410X

- Graves, Robert. The Greek Myths (Complete Edition). London: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0140171991

- Harrison, Jane Ellen. Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1908.

- Kerenyi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. London and New York: Thames and Hudson, 1951. ISBN 0500270481

- Mikalson, Jon D. Ancient Greek Religion. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005. ISBN 0631232222

- Parke, H. W. Festivals of the Athenians. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1977. ISBN 0801410541

- Powell, Barry B. Classical Myth, 2nd ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1998. ISBN 0137167148

- Rose, H. J. A Handbook of Greek Mythology. New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1959. ISBN 0525470417

- Salmonson, Jessica Amanda. The Encyclopedia of Amazons. New York: Paragon House, 1991. ISBN 1557784205

- Vol, Mary. "Athene (Athena) and Artemis" in Seppo Sakari Telenius, Athena-Artemis. Helsinki: Kirja Kerrallaan, 2006. ISBN 9529205600

- Ventris, Michael and John Chadwick. Documents in Mycenaean Greek, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973. ISBN 0521085586

External links

All links retrieved August 16, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.