Alfred de Musset

| Alfred de Musset | |

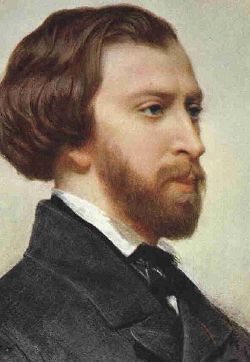

Musset painted by Charles Landelle

| |

| Born | Alfred Louis Charles de Musset-Pathay December 11 1810 Paris, France |

|---|---|

| Died | May 2 1857 (aged 46) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Poet, dramatist |

| Signature | |

Alfred Louis Charles de Musset-Pathay (French pronunciation: [al.fÊÉd dÉ my.sÉ]; December 11, 1810 â May 2, 1857) was a French dramatist, poet, and novelist. Along with his poetry, he is known for writing the autobiographical novel La Confession d'un enfant du siècle (The Confession of a Child of the Century). The novel was based on his celebrated affair with the writer George Sand.

De Musset was a republican. He opposed the July Revolution of 1830 due to its violence. His play "Lorenzaccio" uses the events in sixteenth century Florence as political commentary on the events of the July 1830 Revolution and the July Monarchy.

Biography

Musset was born in Paris. His family was upper-class but poor. His father worked in various key government positions, but never gave his son any money. Musset's mother came from similar circumstances, and her role as a society hostess â for example her drawing-room parties, luncheons and dinners held in the Musset residence â left a lasting impression on young Alfred.[1]

An early indication of his boyhood talents was his fondness for acting impromptu mini-plays based upon episodes from old romance stories he had read. Years later, elder brother Paul de Musset would preserve these and many other details, for posterity, in a biography of his famous younger brother.[1]

Alfred de Musset entered the lycée Henri-IV at the age of nine, where in 1827 he won the Latin essay prize in the Concours général. With the help of Paul Foucher, Victor Hugo's brother-in-law, he began to attend, at the age of 17, the Cénacle, the literary salon of Charles Nodier at the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal. After attempts at careers in medicine (which he gave up owing to a distaste for dissections), law,[2] drawing, English and piano, he became one of the first Romantic writers. His first collection of poems was Contes d'Espagne et d'Italie (1829, Tales of Spain and Italy).[2] By the time he reached the age of 20, his rising literary fame was already accompanied by a sulphurous reputation fed by his dandy side.

He was the librarian of the French Ministry of the Interior under the July Monarchy. His politics were liberal. He was on good terms with the family of King Louis Philippe.[3] During this time he also involved himself in polemics during the Rhine crisis of 1840, caused by the French prime minister Adolphe Thiers, who as Minister of the Interior had been Musset's superior. Thiers had demanded that France should own the left bank of the Rhine (described as France's "natural boundary"), as it had under Napoleon, despite the territory's German population. These demands were rejected by German songs and poems, including Nikolaus Becker's Rheinlied, which contained the verse: "Sie sollen ihn nicht haben, den freien, deutschen Rhein ..." (They shall not have it, the free, German Rhine). Musset answered to this with a poem of his own: "Nous l'avons eu, votre Rhin allemand" (We've had it, your German Rhine).

Relationship with Georges Sand

The tale of his celebrated love affair with George Sand in 1833â1835[2] is told from his point of view in his autobiographical novel La Confession d'un Enfant du Siècle (The Confession of a Child of the Century) (1836),[2] which was made into a 1999 film, Children of the Century, and a 2012 film, Confession of a Child of the Century, and is told from her point of view in her Elle et lui (1859). Musset's Nuits (Nights) (1835â1837) traces the emotional upheaval of his love for Sand from early despair to final resignation.[2] He is also believed to be the anonymous author of Gamiani, or Two Nights of Excess (1833), a lesbian erotic novel also believed to be modeled on Sand.[4]

Outside of his relationship with Sand he was a well-known figure in brothels, and is widely accepted to be the anonymous author-client who beat and humiliated the author and courtesan Céleste de Chabrillan, also known as La Mogador.

Musset was dismissed from his post as librarian by the new minister Ledru-Rollin after the revolution of 1848. He was, however, appointed librarian of the Ministry of Public Instruction in 1853.

On April 24, 1845, Musset received the Légion d'honneur at the same time as Balzac, and was elected to the Académie Française in 1852 after two failed attempts in 1848 and 1850.

Death

Alfred de Musset died in his sleep in Paris in 1857. The cause was heart failure, the combination of alcoholism and a longstanding aortic insufficiency. One symptom that had been noticed by his brother was a bobbing of the head as a result of the amplification of the pulse. This was later called de Musset's sign.[5] He was buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

Plays

"Lorenzaccio" (1833) is set in sixteenth-century Florence. It depicts Lorenzino de' Medici, who killed Florence's tyrant, Alessandro de' Medici, his cousin.[6] Having engaged in debaucheries to gain the Duke's confidence, he loses the trust of Florence's citizens, earning the insulting surname "Lorenzaccio". Though he kills Alessandro, he knows he will never return to his former state. Since opponents to the tyrant's regime fail to use Alessandro's death as a way to overthrow the dukedom and establish a republic, Lorenzo's action does not appear to aid the people's welfare.

Written soon after the July revolution of 1830, at the start of the July Monarchy, when King Louis Philippe I overthrew King Charles X of France, the play contains many cynical comments on the lack of true republican sentiments in the face of violent overthrow.

The play was inspired by George Sand's Une conspiration en 1537, in turn inspired by Varchi's chronicles. As much of Romantic tragedy, including plays by Victor Hugo, it was influenced by William Shakespeare's Hamlet.

Un caprice (1837) was the first theatrical success for de Musset. It was first performed in 1843 at the French theater in Saint Petersburg, the Mikhaylovsky Theater, then in France at the Comédie-Française on November 27, 1847. The play deals with the story of Mathilde, a beautiful and innocent young girl married to a libertine, Mr. de Chavigny. [[It focuses on their marital struggles. Jules Janin praised the play in Le Journal des débats and Théophile Gautier stated in La Presse that the play was "a great literary achievement".

Legacy

Literary

The French poet Arthur Rimbaud was highly critical of Musset's work. Rimbaud wrote in his Letters of a Seer (Lettres du Voyant) that Musset did not accomplish anything because he "closed his eyes" before the visions (letter to Paul Demeny, May 1871).

Director Jean Renoir's La règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game) was inspired by Musset's play Les Caprices de Marianne.

Henri Gervex's 1878 painting Rolla was based on a poem by de Musset. It was rejected by the jury of the Salon de Paris for immorality, since it features suggestive metaphors in a scene from the poem, with a naked prostitute shown after having sex with her client, but the controversy helped Gervex's career.

Jean Anouilh's Eurydice (1941) employs an intertextually salient quote of Musset's play On ne badine pas avec l'amour (You don't mess with love) II.5 (1834), "The Tirade of Perdican" â Vincent and Eurydice's Mother rekindle the glorious days of their earlier acting careers and their own amours, when once his on-stage performance of Perdican's tirade instigated their first dressing-room love scene.

Music

Numerous (often French) composers wrote works using Musset's poetry during the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

- Opera

Georges Bizet's opera Djamileh (1871, with a libretto by Louis Gallet) is based on Musset's story Namouna.[7] In 1872 Offenbach composed an opéra comique Fantasio with a libretto by Paul de Musset closely based on the 1834 play of the same name by his brother Alfred.[8] Dame Ethel Smyth composed an opera based on the same work, that premiered in Weimar in 1898. The play La Coupe et les lèvres was the basis of Giacomo Puccini's opera Edgar (1889). Fortunio, a four-act opera by André Messager is based on Musset's 1835 comedy Le Chandelier. Les caprices de Marianne, a two-act opéra comique by Henri Sauguet (1954) is based on the play by Musset.[9] The opera Andrea del Sarto (1968) by French composer Daniel-Lesur was based on Musset's play André del Sarto. Lorenzaccio, which takes place in Medici's Florence, was set to music by the musician Sylvano Bussotti in 1972.

- Song

Bizet set Musset's poems "à une fleur" and "Adieux à Suzon" for voice and piano in 1866; the latter had previously been set by Chabrier in 1862. Pauline Viardot set Musset's poem "Madrid" for voice and piano as part of her 6 Mélodies (1884). The Welsh composer Morfydd Llwyn Owen wrote song settings for Musset's "La Tristesse" and "Chanson de Fortunio". Lili Boulanger's Pour les funérailles d'un soldat for baritone, mixed chorus and orchestra is a setting of several lines from Act IV of Musset's play La Coupe et les lèvres.

- Instrumental music

Ruggero Leoncavallo's symphonic poem La Nuit de Mai (1886) was based on Musset's poetry. Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco's Cielo di settembre, op. 1 for solo piano (1910) takes its name from a line of Musset's poem "A quoi rêvent les jeunes filles". The score, in the original publication, is preceded by that line, "Mais vois donc quel beau ciel de septembreâ¦" Rebecca Clarke's Viola Sonata (1919) is prefaced by two lines from Musset's La Nuit de Mai.[10]

Quotations

- "How glorious it is â and also how painful â to be an exception."[11]

- "Man is a pupil, pain is his teacher."[12]

- "Verity is nudity."[13]

- Romanticism is the abuse of adjectives. [14]

Works

Poetry

- à Mademoiselle Zoé le Douairin (1826)

- Un rêve (1828)

- Contes d'Espagne et d'Italie (1830)

- La Quittance du diable (1830)

- La Coupe et les lèvres (1831)

- Namouna (1831)

- Rolla (1833)

- Perdican (1834)

- Camille et Rosette (1834)

- L'Espoir en Dieu (1838)

- La Nuit de mai (1835)

- La Nuit de décembre (1835)

- La Nuit d'août (1836)

- La Nuit d'octobre (1837)

- La Nuit d'avril (1838)

- Chanson de Barberine (1836)

- Ã la Malibran (1837)

- Tristesse (1840)

- Une Soirée perdue (1840)

- Souvenir (1841)

- Le Voyage où il vous plaira (1842)

- Sur la paresse (1842)

- Après une lecture (1842)

- Les Filles de Loth (1849)

- Carmosine (1850)

- Bettine (1851)

- Faustine (1851)

- Åuvres posthumes (1860)

Plays

- La Quittance du diable (1830)

- La Nuit vénitienne (1830)

- a failure; from this time until 1847, his plays were published but not performed

- La Coupe et les lèvres (1831)

- à quoi rêvent les jeunes filles (1832)

- André del Sarto (1833)

- Les Caprices de Marianne (1833)

- Lorenzaccio (1833)

- Fantasio (1834)

- On ne badine pas avec l'amour (1834)

- La Quenouille de Barberine (1835)

- Le Chandelier (1835)

- Il ne faut jurer de rien (1836)

- Faire sans dire (1836)

- Un Caprice (1837)

- first performed in 1847, and a huge success, leading to the performance of other plays

- Il faut qu'une porte soit ouverte ou fermée (1845)

- L'Habit vert (1849)

- Louison (1849)

- On ne saurait penser à tout (1849)

- L'Ãne et le Ruisseau (1855)

Novels

- La Confession d'un enfant du siècle (The Confession of a Child of the Century, 1836)[1]

- Histoire d'un merle blanc (The White Blackbird, 1842)

Short stories and novellas

- Emmeline (1837)

- Le Fils du Titien (1838)

- Frédéric et Bernerette (1838)

- Margot (1838)

- Croisilles (1839)

- Les Deux Maîtresses (1840)

- Histoire d'un merle blanc (1842)

- Pierre et Camille (1844)

- Le Secret de Javotte (1844)

- Les Frères Van Buck (1844)

- Mimi Pinson (1845)

- La Mouche (1853)

In English translation

- A Good Little Wife (1847)

- Selections from the Prose and Poetry of Alfred de Musset (1870)

- Tales from Alfred de Musset (1888)

- The Beauty Spot (1888)

- Old and New (1890)

- The Confession of a Child of the Century (1892)

- Barberine (1892)

- The Complete Writings of Alfred de Musset (1907)

- The Green Coat (1914)

- Fantasio (1929)

- Camille and Perdican (1961)

- Historical Dramas (1997)

- Lorenzaccio (1998)

- Twelve Plays (2001)

Selected filmography

- On ne badine pas avec l'amour, directed by Gaston Ravel and Tony Lekain (France, 1924, based on the play On ne badine pas avec l'amour)

- Mimi Pinson, directed by Théo Bergerat (France, 1924, based on the poem Mimi Pinson)

- Hon, den enda, directed by Gustaf Molander (Sweden, 1926, based on the play Il ne faut jurer de rien)

- One Does Not Play with Love, directed by G. W. Pabst (Germany, 1926, based on the play On ne badine pas avec l'amour)

- The Rules of the Game, directed by Jean Renoir (France, 1939, inspired by the play Les Caprices de Marianne)

- Lorenzaccio, directed by Raffaello Pacini (Italy, 1951, based on the play Lorenzaccio)

- Mimi Pinson, directed by Robert Darène (France, 1958, based on the poem Mimi Pinson)

- No Trifling with Love, directed by Caroline Huppert (France, 1977, TV film, based on the play On ne badine pas avec l'amour)

- La Confession d'un enfant du siècle, directed by Claude Santelli (France, 1974, TV film, based on the novel Confession d'un enfant du siècle)

- Le Chandelier, directed by Claude Santelli (France, 1977, TV film, based on the play Le Chandelier)

- Il ne faut jurer de rien, directed by Ãric Civanyan (France, 2005, based on the play Il ne faut jurer de rien)

- Confession of a Child of the Century, directed by Sylvie Verheyde (France, 2012, based on the novel Confession d'un enfant du siècle)

- Two Friends, directed by Louis Garrel (France, 2015, loosely based on the play Les Caprices de Marianne)

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 Robert T. Tuohey, "Chessville â Alfred de Musset: Romantic Player", Chessville, 2006. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 His names are often reversed as "Louis Charles Alfred de Musset."

- â The Spectator, Volume 50 (F.C. Westley, 1877), 983.

- â Barbara Kendall-Davies, The Life and Work of Pauline Viardot Garcia (Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2003, ISBN 1904303277), 45-46. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- â Tsung O. Cheng M.D., "Twelve eponymous signs of aortic regurgitation, one of which was named after a patient instead of a physician," The American Journal of Cardiology 93(10) (May 15, 2004): 1332â3.

- â Alfred de Musset, English text of Lorenzaccio," The Complete Writings of Alfred de Musset, (New York, Privately published, 1906). Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- â Hugh Macdonald, "Djamileh," The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- â Andrew Lamb, "Jacques Offenbach," The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London, U.K. and New York, NY: Macmillan, 1997, ISBN 978-0935859928).

- â A. Hoérée & Langham Smith R. Henri Sauguet, Les caprices de Marianne in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera (London and New York, Macmillian, 1997, ISBN 978-0935859928).

- â Liane Curtis, "Clarke, Rebecca," Oxford Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- â W. H. Auden and Louis Kronenberger, The Viking Book of Aphorisms (New York, NY: Viking Press, 1966).

- â "A quote by Alfred de Musset," Goodreads. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- â Maturin Murray Ballou, "Pearls of Thought," (Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1881), 266. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- â [1] They Said So. Retrieved May 4, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Affron, Charles. A Stage For Poets: Studies in the Theatre of Hugo and Musset. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1971. ISBN 978-0691062013

- Auden, W.H., and Louis Kronenberger. The Viking Book of Aphorisms. New York, NY: Viking Press, 1966.

- Ballou, Maturin Murray. "Pearls of Thought,". Boston, MA: Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1881. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Bishop, Lloyd. The Poetry of Alfred de Musset. Styles and Genres. New York, NY: Peter Lang, 1987. ISBN 978-0820403571

- Croce, Benedetto. "De Musset," in European Literature in the Nineteenth Century. London, U.K.: Chapman & Hall, 1924, Â 252â266. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- de Musset, Alfred. English text of Lorenzaccio," The Complete Writings of Alfred de Musset. New York, Privately published, 1906. Retrieved April 19, 2023.

- Gochberg, Herbert S. Stage of Dreams: The Dramatic Art of Alfred de Musset (1828-1834). Geneva, SZ: Librairie Droz, 1967.

- Hoérée, A., and Langham Smith R. Henri Sauguet. Les caprices de Marianne in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. London and New York, Macmillian, 1997. ISBN 978-0935859928

- Kendall-Davies, Barbara. The Life and Work of Pauline Viardot Garcia. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2003. ISBN 1904303277

- Kamb, Andrew. "Jacques Offenbach," The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. London, U.K. and New York, NY: Macmillan, 1997. ISBN 978-0935859928

- Majewski, Henry F. Paradigm & Parody: Images of Creativity in French Romanticism - Vigny, Hugo, Balzac, Gautier, Musset. Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1989. ISBN 978-0813911779

- Rees, Margaret A. Alfred de Musset. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers, 1971. ISBN 978-0805726466

- Sedgewick, Henry D. Alfred de Musset, 1810â1857. Indianapolis, IN: BobbsâMerrill Company, 1931.

- Sices, David. The Theatre of Solitude. The Drama of Alfred de Musset. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1974. ISBN 978-0874510836

Further reading

- "Alfred de Musset, Poet", The Edinburgh Review (CCIV) (1906): Â 103â132. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Barine, Arvède, The Life of Alfred de Musset. New York, N.Y.: Edwin C. Hill Company, 1906. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Besant, Walter, "Alfred de Musset," in Essays and Historiettes. London, U.K.: Chatto & Windus, 1893, Â 144â169. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Beus, Yifen "Alfred de Musset's Romantic Irony," Nineteenth-Century French Studies XXXI(3/4) (2003): Â 197â209.

- Bishop, Lloyd, "Romantic Irony in Musset's 'Namouna'," Nineteenth-Century French Studies VII(3/4) (1979): Â 181â191.

- Bourcier, Richard J., "Alfred de Musset: Poetry and Music" The American Benedictine Review (XXXV) (1984): Â 17â24.

- Brandes, Georg, Main Currents in Nineteenth Century Literature, Vol. V. New York, N.Y.: The Macmillan Company, 1904, Â 90â131. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Denommé, Robert Thomas, Nineteenth-century French Romantic Poets. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 1969, ISBN 978-0809303434.

- Gamble, D.R., "Alfred de Musset and the Uses of Experience" Nineteenth-Century French Studies XVIII(1/2) (1989-1990): Â 78â84.

- Gooder, Jean, "Alive or Dead? Alfred de Musset's Supper with Rachel" The Cambridge Quarterly XV(2) (1986): Â 173â187.

- Grayson Jane, "The French Connection: Nabokov and Alfred de Musset: Ideas and Practices of Translation" The Slavonic and East European Review LXXIII(4) (1996): Â 613â658.

- Greet, Anne Hyde, "Humor in the Poetry of Alfred de Musset" Studies in Romanticism VI(3) (1967): Â 175â192.

- James, Henry, "Alfred de Musset," in French Poets and Novelists. London, U.K.: Macmillan & Co., 1878), Â 1â38. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Lefebvre, Henri, Musset: Essai. Paris, FR: L'Arche, 1970.

- Levin, Susan, The Romantic Art of Confession. Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1998, ISBN 978-1571131898.

- Mauris, Maurice, "Alfred de Musset," in French Men of Letters. New York, N.Y.: D. Appleton and Company, 1880, Â 35â65. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Mossman, Carol, Writing with a Vengeance: The Countess de Chabrillan's Rise from Prostitution. Toronto, CA: University of Toronto Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1442697775.

- Musset, Paul de, The Biography of Alfred de Musset. Boston, MA: Roberts Brothers, 1877. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Oliphant, Cyril Francis, Alfred de Musset. Edinburgh, U.K.: William Blackwood and Sons, 1890. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Padgett, Graham, "Bad Faith in Alfred de Musset: A Problem of Interpretation" Dalhousie French Studies (III) (1981) Â 65â82.

- Palgrave, Francis T., "The Works of Alfred de Musset," in Oxford Essays. London, U.K.: John W. Parker, 1855, Â 80â104. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Pitwood, Michael, "Musset," in Dante and the French Romantics. Genève, SZ: Librairie Droz, 1985, ISBN 978-2600036153,  209â217.

- Pollock, Walter Herries, "Alfred de Musset," in Lectures on French Poets. London, U.K.: C. Kegan Paul & Co., 1879, Â 43â96. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Rees, Margaret A., "Imagery in the Plays of Alfred de Musset," The French Review XXXVI(3) (1963): Â 245â254.

- Sainte-Beuve, C.A., "Alfred de Musset" in Portraits of Men. London, U.K.: David Scott, 1891, Â 23â35. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Stothert, James, "Alfred de Musset" The Gentleman's Magazine, (CCXLIII) (1878): Â 215â234. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Thomas, Merlin, "Alfred de Musset: Don Juan on the Boulevard de Gand" in Myths and its Making in the French Theatre: Studies Presented to W. D. Howarth. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0521321884, Â 158â165.

- Trent, William P., "Tennyson and Musset Once More" in The Authority of Criticism. New York, N.Y.: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1899, Â 269â291. Retrieved April 29, 2023.

- Wright, Rachel L., "Male Reflectors in the Drama of Alfred de Musset" The French Review LXV(3) (1992): Â 393â401.

External links

Links retrieved April 19, 2023.

- Works by Alfred de Musset. Project Gutenberg

| Romanticism | |

|---|---|

| Eighteenth century - Nineteenth century | |

| Romantic music: Beethoven - Berlioz - Brahms - Chopin - Grieg - Liszt - Puccini - Schumann - Tchaikovsky - The Five - Verdi - Wagner | |

|   Romantic poetry: Blake - Burns - Byron - Coleridge - Goethe - Hölderlin - Hugo - Keats - Lamartine - Leopardi - Lermontov - Mickiewicz - Nerval - Novalis - Pushkin - Shelley - SÅowacki - Wordsworth   | |

| Visual art and architecture: Brullov - Constable - Corot - Delacroix - Friedrich - Géricault - Gothic Revival architecture - Goya - Hudson River school - Leutze - Nazarene movement - Palmer - Turner | |

| Romantic culture: Bohemianism - Romantic nationalism | |

| << Age of Enlightenment | Victorianism >> Realism >> |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.