Ojibwa

| This article contains Canadian Aboriginal syllabic characters. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of syllabics. |

| Ojibwa |

|---|

Crest of the Ojibwa people |

| Total population |

| 175,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States, Canada |

| Languages |

| English, Ojibwe |

| Religions |

| Catholicism, Methodism, Midewiwin |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Ottawa, Potawatomi and other Algonquian peoples |

The Ojibwa or Chippewa (also Ojibwe, Ojibway, Chippeway) is the largest group of Native Americans-First Nations north of Mexico, including Métis. They are the third largest in the United States, surpassed only by Cherokee and Navajo. They are equally divided between the United States and Canada. Because they were formerly located mainly around Sault Ste. Marie, at the outlet of Lake Superior, the French referred to them as Saulteurs. Ojibwa who subsequently moved to the prairie provinces of Canada have retained the name Saulteaux. Ojibwa who were originally located about the Mississagi River and made their way to southern Ontario are known as the Mississaugas.

As a major component group of the Anishinaabe peoples—which includes the Algonquin, Nipissing, Oji-Cree, Odawa and the Potawatomi—the Ojibwe peoples number over 100,000 in the U.S., living in an area stretching across the north from Michigan to Montana. Another 76,000, in 125 bands, live in Canada, stretching from western Québec to eastern British Columbia. They are known for their birch bark canoes, sacred birch bark scrolls, the use of cowrie shells, wild rice, copper points, and for their use of gun technology from the British to defeat and push back the Dakota nation of the Sioux (1745). The Ojibwe Nation was the first to set the agenda for signing more detailed treaties with Canada's leaders before many settlers were allowed too far west. The Midewiwin Society is well respected as the keeper of detailed and complex scrolls of events, history, songs, maps, memories, stories, geometry, and mathematics.

Names

The name Ojibwe (plural: Ojibweg) is commonly anglicized as "Ojibwa." The name "Chippewa" is an anglicized corruption of "Ojibwa." Although many variations exist in literature, "Chippewa" is more common in the United States and "Ojibwa" predominates in Canada, but both terms do exist in both countries. The exact meaning of the name "Ojibwe" is not known; the most common explanations on the name derivations are:

- from ojiibwabwe (/o/ + /jiibw/ + /abwe/), meaning "those who cook\roast until it puckers," referring to their fire-curing of moccasin seams to make them water-proof (Roy 2008), though some sources instead say this was a method of torture the Ojibwe implemented upon their enemies (Warren 1984).

- from ozhibii'iwe (/o/ + /zhibii'/ + /iwe/), meaning "those who keep records [of a Vision]," referring to their form of pictorial writing, and pictographs used in Midewiwin rites (Erdrich 2003).

- from ojiibwe (/o/ + /jiib/ + /we/), meaning "those who speak-stiffly"\"those who stammer," referring to how the Ojibwe sounded to the Cree (Johnston 2007).

The Saulteaux (also Salteaux pronounced [ˈsoʊtoʊ]) are a First Nation in Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia, Canada, a branch of the Ojibwa. Saulteaux is a French language term meaning "people of the rapids," referring to their former location about Sault Ste. Marie.

The Ojibwa/Chippewa are part of the Anishinaabe peoples, together with the Odawa and Algonkin peoples. Anishnaabeg (plural form) means "First- or Original-Peoples" or it may refer to "the good humans," or good people, that are on the right road/path given to them by the Creator or gitchi-manitou (Anishinaabeg term for God). In many Ojibwa communities throughout Canada and the U. S., the more generalized name Anishinaabe(-g) is becoming more commonly used as a self-description.

Language

The Ojibwe language is known as Anishinaabemowin or Ojibwemowin, and is still widely spoken. The language belongs to the Algonquian linguistic group, and is descended from Proto-Algonquian. Its sister languages include Blackfoot, Cheyenne, Cree, Fox, Menominee, Potawatomi, and Shawnee. Anishinaabemowin is frequently referred to as a "Central Algonquian" language; however, Central Algonquian is an areal grouping rather than a genetic one. Ojibwemowin is the fourth most spoken Native language in North America (after Navajo, Cree, and Inuktitut). Many decades of fur trading with the French established the language as one of the key trade languages of the Great Lakes and the northern Great Plains.

The Ojibwe presence was made highly visible among non-Native Americans and around the world by the popularity of the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha, written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in 1855. The epic contains many toponyms that originate from Ojibwa words.

History

Pre-contact

According to their tradition, and from recordings in birch bark scrolls, many Ojibwe came from the eastern areas of North America, or Turtle Island, and from along the east coast. They traded widely across the continent for thousands of years and knew of the canoe routes west and a land route to the west coast. According to the oral history, seven great miigis (radiant/iridescent) beings appeared to the peoples in the Waabanakiing (Land of the Dawn, i.e. Eastern Land) to teach the peoples of the mide way of life. However, one of the seven great miigis beings was too spiritually powerful and killed the peoples in the Waabanakiing when the people were in its presence. The six great miigis beings remained to teach while the one returned into the ocean. The six great miigis beings then established doodem (clans) for the peoples in the east. Of these doodem, the five original Anishinaabe doodem were the Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi (Echo-maker, i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke (Tender, i.e., Bear) and Moozoonsii (Little Moose), then these six miigis beings returned into the ocean as well. If the seventh miigis being stayed, it would have established the Thunderbird doodem.

At a later time, one of these miigis beings appeared in a vision to relate a prophecy. The prophecy stated that if more of the Anishinaabeg did not move further west, they would not be able to keep their traditional ways alive because of the many new settlements and European immigrants that would arrive soon in the east. Their migration path would be symbolized by a series of smaller Turtle Islands, which was confirmed with miigis shells (i.e., cowry shells). After receiving assurance from the their "Allied Brothers" (i.e., Mi'kmaq) and "Father" (i.e., Abnaki) of their safety in having many more of the Anishinaabeg move inland, they advanced along the St. Lawrence River to the Ottawa River to Lake Nipissing, and then to the Great Lakes. First of these smaller Turtle Islands was Mooniyaa, which Mooniyaang (Montreal, Quebec) now stands. The "second stopping place" was in the vicinity of the Wayaanag-gakaabikaa (Concave Waterfalls, i.e. Niagara Falls). At their "third stopping place" near the present-day city of Detroit, Michigan, the Anishinaabeg divided into six divisions, of which the Ojibwa was one of these six. The first significant new Ojibwa culture-centre was their "fourth stopping place" on Manidoo Minising (Manitoulin Island). Their first new political-centre was referred as their "fifth stopping place," in their present country at Baawiting (Sault Ste. Marie).

Continuing their westward expansion, the Ojibwa divided into the "northern branch" following the north shore of Lake Superior, and "southern branch" following the south shore of the same lake. In their expansion westward, the "northern branch" divided into a "westerly group" and a "southerly group." The "southern branch" and the "southerly group" of the "northern branch" came together at their "sixth stopping place" on Spirit Island () located in the St. Louis River estuary of Duluth/Superior region where the people were directed by the miigis being in a vision to go to the "place where there is food (i.e. wild rice) upon the waters." Their second major settlement, referred as their "seventh stopping place," was at Shaugawaumikong (or Zhaagawaamikong, French, Chequamegon) on the southern shore of Lake Superior, near the present La Pointe near Bayfield, Wisconsin. The "westerly group" of the "northern branch" continued their westward expansion along the Rainy River, Red River of the North, and across the northern Great Plains until reaching the Pacific Northwest. Along their migration to the west they came across many miigis, or cowry shells, as told in the prophecy.

Post-contact with Europeans

The first historical mention of the Ojibwe occurs in the Jesuit Relation of 1640. Through their friendship with the French traders, they were able to obtain guns and thus successfully end their hereditary wars with the Sioux and Fox on their west and south. The Sioux were driven out from the Upper Mississippi region, and the Fox were forced down from northern Wisconsin and compelled to ally with the Sauk. By the end of the 18th century, the Ojibwa were the nearly unchallenged owners of almost all of present-day Michigan, northern Wisconsin, and Minnesota, including most of the Red River area, together with the entire northern shores of Lakes Huron and Superior on the Canadian side and extending westward to the Turtle Mountains of North Dakota, where they became known as the Plains Ojibwa or Saulteaux.

The Ojibwa were part of a long term alliance with the Ottawa and Potawatomi peoples, called the Council of Three Fires and which fought with the Iroquois Confederacy and the Sioux. The Ojibwa expanded eastward, taking over the lands alongside the eastern shores of Lake Huron and Georgian Bay. The Ojibwa allied with the French in the French and Indian War, and with the British in the War of 1812.

In the U.S., the government attempted to remove all the Ojibwa to Minnesota west of Mississippi River, culminating in the Sandy Lake Tragedy and several hundred deaths. Through the efforts of Chief Buffalo and popular opinion against Ojibwa removal, the bands east of the Mississippi were allowed to return to permanent reservations on ceded territory. A few families were removed to Kansas as part of the Potawatomi removal.

In British North America, the cession of land by treaty or purchase was governed by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, and subsequently most of the land in Upper Canada was ceded to Great Britain. Even with the Jay Treaty signed between the Great Britain and the United States, the newly formed United States did not fully uphold the treaty, causing illegal immigration into Ojibwa and other Native American lands, which culminated in the Northwest Indian War. Subsequently, much of the lands in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, parts of Illinois and Wisconsin, and northern Minnesota and North Dakota were ceded to the United States. However, provisions were made in many of the land cession treaties to allow for continued hunting, fishing and gathering of natural resources by the Ojibwe even after the land sales. In northwestern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta, the numbered treaties were signed. British Columbia had no signed treaties until the late 20th century, and most areas have no treaties yet. There are ongoing treaty land entitlements to settle and negotiate. The treaties are constantly being reinterpreted by the courts because many of them are vague and difficult to apply in modern times. However, the numbered treaties were some of the most detailed treaties signed for their time. The Ojibwa Nation set the agenda and negotiated the first numbered treaties before they would allow safe passage of many more settlers to the prairies.

Often, earlier treaties were known as "Peace and Friendship Treaties" to establish community bonds between the Ojibwa and the European settlers. These earlier treaties established the groundwork for cooperative resource sharing between the Ojibwa and the settlers. However, later treaties involving land cessions were seen as territorial advantages for both the United States and Canada, but the land cession terms were often not fully understood by the Ojibwa because of the cultural differences in understanding of the land. For the governments of the US and Canada, land was considered a commodity of value that could be freely bought, owned and sold. For the Ojibwa, land was considered a fully-shared resource, along with air, water and sunlight; concept of land sales or exclusive ownership of land was a foreign concept not known to the Ojibwa at the time of the treaty councils. Consequently, today in both Canada and the US, legal arguments in treaty-rights and treaty interpretations often bring to light the differences in cultural understanding of these treaty terms in order to come to legal understanding of the treaty obligations.

During Indian Removal, US government attempted to relocate tribes from to west of the Mississippi River as the white pioneers colonized the areas. But in the late 19th century, the government instead moved the tribes onto reservations. The government attempted to do this to the Anishinabe in the Keweenaw Peninsula in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan.

Salteaux

Because of their location, they farmed little and were mainly hunters and fishers.

The Saulteaux were originally settled around Lake Superior and Lake Winnipeg, principally in the Sault Ste. Marie and northern Michigan areas. White Canadians and Americans gradually pushed the tribe westwards to Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, with one community in British Columbia. Today most of them live in the Interlake, southern part of Manitoba, and in Saskatchewan; because they lived on land ill-suited for European crops, they were able to keep much of their land. Generally, the Saulteaux are divided into three major divisions.

Ontario Saulteaux

Eastern Saulteaux, bettern known as the Ontario Saulteaux, are located about Rainy Lake, and about Lake of the Woods in Northwestern Ontario and southeastern Manitoba. Many of the Ontario Saulteaux First Nations are signatories to Treaty 3. Their form of Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language) is sometimes called Northwestern Ojibwa language (ISO 639-3: OJB) or simply as Ojibwemowin (Ojibwe language), though English is the first language of many members. The Ontario Saulteaux culture is that of the Eastern Woodlands culture.

Manitoba Saulteaux

Central Saulteaux, bettern known as Manitoba Saulteaux, are found primarily in eastern and southern Manitoba, extending west into southern Saskatchewan. During the late 18th century and early 19th centurty, as partners with the Cree in the fur trade, resulted in the Saulteaux extending themselves from southern Manitoba, northwest into the Swan River and Cumberland districts of west-central Manitoba, and into Saskatchewan along the Assiniboine River as far its confluence with the Souris River. Once established in the area, the Saulteaux adapted some of the cultural traits of their allies, the Plains Cree and Assiniboine. Consequently, together with the Western Saulteaux, the Manitoba Saulteaux are sometimes called Plains Ojibwe. Many of the Manitoba Saulteaux First Nations are signatories to Treaty 1 and Treaty 2. The Manitoba Saulteaux culture is a transitional one from Eastern Woodlands culture of their Ontario Saulteaux neighbours and Plains culture of the Western Saulteaux neighbours. Often, the term "Bungee" (from bangii meaning "a little bit") is used to describe either the Manitoba Saulteaux (who are a little bit like the Cree) or their Métis population (who are a little bit Anishinaabe), with the language used by their Métis population described as the Bungee language.

Western Saulteaux

Western Saulteaux are found primarily in central Saskatchewan, but extend east into southwestern Manitoba and west into central Alberta and eastern British Columbia. These Saulteaux call themselves Nakawē (ᓇᐦᑲᐌ)—a general term for the Saulteaux. To the neighbouring Plains Cree, they are known as the Nahkawiyiniw (ᓇᐦᑲᐏᔨᓂᐤ), a word of related etymology. Their form of Anishinaabemowin (Anishinaabe language), known as Nakawēmowin (ᓇᐦᑲᐌᒧᐎᓐ) or Western Ojibwa language (ISO 639-3: OJW), is an Algonquian language, although like most First Nations, English is the first language of most members. Many of the Western Saulteaux First Nations are signatories to Treaty 4 and Treaty 6. The Western Saulteaux culture is that of the Plains culture.

Culture

The Ojibwa live in groups (otherwise known as "bands"). Most Ojibwa, except for the Plains bands, lived a sedentary lifestyle, engaging in fishing, hunting, the farming of maize and squash, and the harvesting of Manoomin (wild rice). Their typical dwelling was the wiigiwaam (wigwam), built either as a waaginogaan (domed-lodge) or as a nasawa'ogaan (pointed-lodge), made of birch bark, juniper bark and willow saplings. They also developed a form of pictorial writing used in religious rites of the Midewiwin and recorded on birch bark scrolls and possibly on rock. The many complex pictures on the sacred scrolls communicate a lot of historical, geometrical, and mathematical knowledge. Ceremonies also used the miigis shell (cowry shell), which is naturally found in far away coastal areas; this fact suggests that there was a vast trade network across the continent at some time. The use and trade of copper across the continent is also proof of a very large area of trading that took place thousands of years ago, as far back as the Hopewell culture. Certain types of rock used for spear and arrow heads were also traded over large distances. The use of petroforms, petroglyphs, and pictographs was common throughout their traditional territories. Petroforms and medicine wheels were a way to teach the important concepts of four directions, astronomical observations about the seasons, and as a memorizing tool for certain stories and beliefs.

During the summer months, the people attend jiingotamog for the spiritual and niimi'idimaa for a social gathering (pow-wows or "pau waus") at various reservations in the Anishinaabe-Aki (Anishinaabe Country). Many people still follow the traditional ways of harvesting wild rice, picking berries, hunting, making medicines, and making maple sugar. Many of the Ojibwa take part in sun dance ceremonies across the continent. The sacred scrolls are kept hidden away until those that are worthy and respect them are given permission to see them and interpret them properly.

The Ojibwa would bury their dead in a burial mound; many erect a jiibegamig or a "spirit-house" over each mound. Instead of a headstone with the deceased's name inscribed upon it, a traditional burial mound would typically have a wooden marker, inscribed with the deceased's doodem. Because of the distinct features of these burials, Ojibwa graves have been often looted by grave robbers. In the United States, many Ojibwa communities safe-guard their burial mounds through the enforcement of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act.

The Ojibwa viewed the world in two types: animate and inanimate, rather than male and female genders. As an animate a person could serve the society as a male-role or a female-role. John Tanner, who spent 30 years living as an Ojibwa after having been kidnapped, documented in his Narrative that Ojibwa peoples do not fall into the European ideas of gender and its gender-roles, having people who fulfill mixed gender roles, two-spirits or egwakwe (Anglicised to "agokwa"). A well-known egwakwe warrior and guide in Minnesota history was Ozaawindib. Tanner described Ozaawindib as "This man was one of those who make themselves women, and are called women by the Indians" (Tanner 2007).

Kinship and clan system

Ojibwa understanding of kinship is complex, and includes not only the immediate family but also the extended family. It is considered a modified bifurcate merging kinship system. As with any bifurcate merging kinship system, siblings generally share the same term with parallel-cousins, because they are all part of the same clan. But the modified system allows for younger siblings to share the same kinship term with younger cross-cousins. Complexity wanes further from the speaker's immediate generation, but some complexity is retained with female relatives. For example, ninooshenh is "my mother's sister" or "my father's sister-in-law"—i.e., my parallel-aunt—but also "my parent's female cross-cousin." Great-grandparents and older generations, as well as great-grandchildren and younger generations are collectively called aanikoobijigan. This system of kinship speaks of the nature of the Anishinaabe's philosophy and lifestyle, that is of interconnectedness and balance between all living generations and all generations of the past and of the future.

The Ojibwe people were divided into a number of odoodeman (clans; singular: odoodem) named primarily for animal totems (pronounced doodem). The five original totems were Wawaazisii (Bullhead), Baswenaazhi ("Echo-maker," i.e., Crane), Aan'aawenh (Pintail Duck), Nooke ("Tender," i.e., Bear) and Moozwaanowe ("Little" Moose-tail). The Crane totem was the most vocal among the Ojibwa, and the Bear was the largest—so large, in fact, that it was sub-divided into body parts such as the head, the ribs and the feet.

Traditionally, each band had a self-regulating council consisting of leaders of the communities' clans or odoodeman, with the band often identified by the principle doodem. In meeting others, the traditional greeting among the Ojibwe peoples is "What is your doodem?" (Aaniin odoodemaayan?) in order to establish a social conduct between the two meeting parties as family, friends or enemies. Today, the greeting has been shortened to "Aaniin."

Spiritual beliefs

The Ojibwa have a number of spiritual beliefs passed down by oral tradition under the Midewiwin teachings. These include a creation myth and a recounting of the origins of ceremonies and rituals. Spiritual beliefs and rituals were very important to the Ojibwa because spirits guided them through life. Birch bark scrolls and petroforms were used to pass along knowledge and information, as well as used for ceremonies. Pictographs were also used for ceremonies. The sweatlodge is still used during important ceremonies about the four directions and to pass along the oral history of the people. Teaching lodges are still common today to teach the next generations about the language and ancient ways of the past. These old ways, ideas, and teachings are still preserved today with these living ceremonies.

In Anishinaabe mythology, particularly among the Ojibwa, Nanabozho is a spirit, and figures prominently in their storytelling, including the story of the world's creation. Nanabozho is the Ojibwe trickster figure and culture hero (these two archetypes are often combined into a single figure in First Nations mythologies). He was the son of Wiininwaa ("Nourishment"), a human mother, and E-bangishimog ("In the West"), a spirit father. Nanabozho most often appears in the shape of a rabbit and is characterized as a trickster. In his rabbit form, he is called Mishaabooz ("Great rabbit" or "Hare") or Chi-waabooz ("Big rabbit"). He was sent to Earth by Gitchi Manitou to teach the Ojibwe, and one of his first tasks was to name all the plants and animals. Nanabozho is considered to be the founder of Midewiwin.

Migration story

According to the oral history of the Anishinaabeg, they originally lived on the shores of the "Great Salt Water" (presumably the Atlantic Ocean near the Gulf of St. Lawrence). They were instructed by seven prophets to follow a sacred miigis shell (whiteshell) toward the west, until they reached a place where food grew upon the water. They began their migration some time around 950, stopping at various points several times along the way, most significantly at Baawitigong, Sault Ste. Marie, where they stayed for a long time, and where two subgroups decided to stay (these became the Potawatomi and Ottawa). Eventually they arrived at the wild ricing lands of Minnesota and Wisconsin (wild rice being the food that grew upon the water) and made Mooningwanekaaning minis (Madeline Island: "Island of the yellow-shafted flicker") their new capital. In total, the migration took around five centuries.

Following the migration there was a cultural divergence separating the Potawatomi from the Ojibway and Ottawa. Particularly, the Potawatomi did not adopt the agricultural innovations discovered or adopted by the Ojibway, such as the Three Sisters crop complex, copper tools, conjugal collaborative farming, and the use of canoes in rice harvest (Waldman 2006). The Potawatomi also divided labor according to gender, much more than the Ojibway and Ottawa did.

Common medicinal plants and their uses

- Asemaa (Tobacco) - Ceremonially, tobacco represents east. Though pure tobacco is commonly used today, traditionally "kinnikinnick"—a giniginige ("mixture") of primarily red osier dogwood with bearberry and tobacco, and occasionally with other additional medicinal plants—was used. The tobacco or its mixture is used in the offering of prayer, acting as a medium for communication. It is either offered through the fire so the smoke can lift the prayers to the Gichi-manidoo, or it is set on the ground in a nice, clean place as an offering. This is done on a daily basis as each new day is greeted with prayers of thankfulness. Tobacco is also the customary offering when seeking knowledge or advice from an Elder or when a Pipe is present.

- Nookwezigan (Smudge stick)

- Mashkodewashk (White sage) - Ceremonially, the sage represents west. It is burned as a purifier.

- Giizhik (White cedar) - Ceremonially, the cedar represents south. The leaves are cleaned from the stems and separated into small pieces which are used in many ways, but when burned, cedar acts as a purifier, cleansing the area in which it is burned.

- Wiingashk (Sweet grass), Hierochloe odorata - Ceremonially, the sweet grass represents north. This, too, is a purifier. When sweet grass is harvested, it is cut rather than pulled and then is often braided because it signifies the hair of Ogashiinan ("Mother Earth"). Sweet grass purifies by replacing negative with positive. Sweet grass does not smell much until it is dried.

Other ceremonial acts and beliefs

- Jiingotamog and Niimi'idimaa (Ceremonial and Secular Pow-wows)

- Sun Dance

- Jingle dress

- Sweat lodge

- madoodiswan (or madoodoo'igan) (sweat lodge)

- madoodoowasin (sweat stone)

- Seven fires prophecy

- Seven Grandfathers

- Nibwaakaawin (wisdom)

- Zaagi'idiwin (mutual love)

- Minaadendamowin (respect)

- Aakode'ewin (bravery)

- Gwayakwaadiziwin (honesty)

- Dabaadendiziwin (humility)

- Debwewin (truth)

- Oshkaabewis - A ceremonial assistant to the Midewinini.

- Drumkeeper

- Firekeeper

- Pipekeeper

- Mizhinawe - A sexton to the Midewiwin ceremony.

Aadizookaan

Traditional stories told by the Anishinaabeg are the basis for the oral legends. Known as the aadizookaanan ("traditional stories," singular aadizookaan), they are told by the debaajimojig ("story-tellers," singular debaajimod) only in winter in order to preserve their transformative powers.

Nanabozho (also known by a variety of other names and spellings, including Wenabozho, Menabozho, and Nanabush) is a trickster figure and culture hero who features as the protagonist of a cycle of stories that serve as the Anishinaabe origin myth. The cycle, which varies somewhat from community to community, tells the story of Nanabozho's conception, birth, and his ensuing adventures, which involve interactions with spirit and animal beings, the creation of the Earth, and the establishment of the Midewiwin. The myth cycle explains the origin of several traditions, including mourning customs, beliefs about the afterlife, and the creation of the sacred plant asemaa (tobacco).

In the aadizookaan many manidoog ("spiritual beings") are encountered. They include, but not limited, to the following.

- Aadizookaanag (singular Aadizookaan) - Manifestation of the traditional teachings, often seen as being the Muses.

- Animikiig ("thunderers," singular animikii) also called "thunderbirds" (binesiwag, singular binesi)

- Aniwye is a skunk spirit and was the first skunk to be given the smell by Nanabozho when he was starving.

- Bagwajiwininiwag - Anishinaabe for Bigfoot or Sasquatch, literally meaning "Wildmen" or "Wildernessmen." In the aadizookaan, they represent honesty.

- Bakaak is a flying skeleton. He is in this form for committing an act of murder and this is form of punishment for that act.

- Earth-Mother, aka Nookomis - "Algonquin legend says that "[b]eneath the clouds [lives] the Earth-Mother from whom is derived the Water of Life, who at her bosom feeds plants, animals and men" (Larousse 428). (8) She is known as Nokomis, the Grandmother." Also known as Ogashiinan ("Dearest Mother"), Omizakamigokwe ("Throughout the Earth Woman") or Giizhigookwe ("Sky Woman").

- E-bangishimog - The west wind, manidoo of ultimate destiny. E-bangishimog is considered to be the father of Majiikiwis, Bapakiwis, Jiibayaabooz and Nanabozho.

- Elbow Witch

- Gaa-biboonikaan - Bringer of winter.

- Gichi-manidoo is the father of life, "The Great Spirit, the Supreme Being"

- Jiibayaabooz - "Spirit Rabbit" who taught methods of communication with the manidoog through dreams, vision quests and purification ceremonies. He is the "Chief of the Underworld."

- Majiikiwis - Eldest son of E-bangishimog and brother of Nanabozho in the aadizookaan but was casted as the father of Hiawatha in The Song of Hiawatha by Longfellow.

- Mandaamin - Maize manidoo

- Memegwesi (or variously as Omemengweshii, Memengwesi, Memegweshi, etc.) - usually described as a hairy-faced river bank-dwelling dwarfs, often travelling in small groups, appearing only to those of "pure mind" and often to children.

- Mishibizhiw (meaning "Great Lynx"; also known as Mishipeshu) is a horned panther living in the waters, often associated with copper. While not strictly evil, Mishibizhiw was greatly feared, and often said to cause drowning deaths.

- Mishi-ginebig (also known as Mishikinebik) is a great horned snake, a powerful underground manidoo that was the guardian spirit brings that brings wisdom and healing.

- Mizaawaabikamoo/Ozaawaabikamoo - Rock manidoo

- Nibiinaabewag/niibinaabekwewag ("Watermen"/"Waterman-women," singular nibiinaabe/nibiinaabekwe) are mermen and mermaids

- Wemicus is a trickster spirit.

- Wiindigoog (singular wiindigoo) are giant, powerful, malevolent cannibalistic spirits associated with the Winter and the North. If a human ever resorts to cannibalism to survive, they are said to become possessed by the spirit of a wiindigoo, and develop an overpowering desire for more human flesh.

- Wiisagejaak - Crane manidoo, also known as "Whiskey Jack"

- Wiininwaa - A woman entitled as "Norishment" who became immortal through manidoowiziwin (the process of taking on qualities of a Manitou); daughter of Nookomis and mother of Nanabozho.

Dreamcatchers

In Ojibwa (Chippewa) culture, a dreamcatcher (or dream catcher; Ojibwe asabikeshiinh, is a handmade object based on a willow hoop, on which is woven a loose net or web. The dreamcatcher is then decorated with personal and sacred items such as feathers and beads.

Traditionally, the Ojibwa construct dreamcatchers by tying sinew strands in a web around a small round or tear-shaped frame (in a way roughly similar to their method for making snowshoe webbing). The resulting "dream-catcher," hung above the bed, is then used as a charm to protect sleeping children from nightmares.

The Ojibwa believe that a dreamcatcher filters a person's dreams: Only good dreams would be allowed to filter through; bad dreams would stay in the net, disappearing with the light of day (Andrews 1997).

Bands

Warren, in his History of the Ojibway People, records 10 major divisions of the Ojibwa in the United States, omitting the Ojibwa located in Michigan, western Minnesota and westward, and all of Canada; if major historical bands located in Michigan and Ontario are added, the count becomes 14:

These 10 major divisions and other major groups that Warren did not record developed into these Ojibwa Bands and First Nations of today.

Contemporary Ojibwa

Several Ojibwa bands in the United States cooperate in the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission, which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Lake Superior-Lake Michigan areas. The commission follows the directives of U.S. agencies to run several wilderness areas. Some Minnesota Ojibwa tribal councils cooperate in the 1854 Treaty Authority, which manages their treaty hunting and fishing rights in the Arrowhead Region. In Michigan, the Chippewa-Ottawa Resource Authority manages the hunting, fishing and gathering rights about Sault Ste. Marie, and the waters of Lake Michigan and Lake Huron. In Canada, the Grand Council of Treaty #3 manages the Treaty 3 hunting and fishing rights around Lake of the Woods.

Notable Ojibwa

Ojibwa people have achieved much in many walks of life—from the chiefs of old to more recent artists, scholars, sportsmen, and activists. The following are a few examples.

- Novelist Louise Erdrich, writer, has written about characters from her culture in Tracks, Love Medicine, and The Bingo Palace.

- Keewaydinoquay Pakawakuk Peschel was a scholar, ethnobotanist, herbalist, medicine woman, teacher, and author. She was an Anishinaabeg Elder of the Crane Clan, born in Michigan around 1919 and spent time on Garden Island, a traditional Anishinaabeg homeland.

- Keith Secola, an award-winning figure in contemporary Native American music, is an Ojibwa originally from Minnesota and holds a degree in American Indian Studies from the University of Minnesota.

- Gerald Vizenor, an enrolled member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, White Earth Reservation, one of the most prolific Native American writers, with over 25 books to his name, he also taught for many years at the University of California, Berkeley, where he was Director of Native American Studies.

- Hanging Cloud (Ojibwa name Ah-shah-way-gee-she-go-qua (Aazhawigiizhigokwe in the contemporary spelling), meaning "Goes Across the Sky Woman") was an Ojibwa woman who was a full warrior (ogichidaakwe in Ojibwe) among her people.

- Ted Nolan, born on the Garden River Ojibwa First Nation Reserve outside of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, Canada served as Head Coach of the Buffalo Sabres and New York Islanders after retirement as a Canadian professional hockey Left Winger. He played three seasons in the National Hockey League for the Detroit Red Wings and Pittsburgh Penguins.

- Jim Northrup, newspaper columnist, poet, performer and political commentator, was born in 1943 on the Fond du Lac Indian Reservation in Minnesota. His Anishinaabe name is "Chibenashi" (from Chi-bineshiinh "Big little-bird").

- O-zaw-wen-dib or Ozaawindib, "Yellow Head" in English) was an Ojibwa warrior who lived in the early nineteenth century and was described as an egwakwe ("agokwa" in literature) or two-spirit—a man who dressed and acted as a woman.

- Dennis Banks a Native American leader, teacher, lecturer, activist and author, was born on Leech Lake Indian Reservation in northern Minnesota. His Ojibwe name, Naawakamig, means "In the Center of the Ground."

- James Bartleman, KStJ, O.Ont grew up in the Muskoka town of Port Carling, a member of the Chippewas of Mnjikaning First Nation. A Canadian diplomat and author, he served as the 27th Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario from 2002 to 2007.

- Chief Buffalo (Ojibwe: Ke-che-waish-ke/Gichi-weshkiinh – "Great-renewer" or Peezhickee/Bizhiki – "Buffalo"; also French, Le Beouf) was an Ojibwa leader born at La Pointe in the Apostle Islands group of Lake Superior, in what is now northern Wisconsin. Recognized as the principal chief of the Lake Superior Chippewa for nearly a half-century until his death in 1855, he led his nation into a treaty relationship with the United States Government signing treaties in 1825, 1826, 1837, 1842, 1847, and 1854. He was also instrumental in resisting the efforts of the United States to remove the Chippewa and in securing permanent reservations for his people near Lake Superior.

- Carl Beam R.C.A., (1943-2005), (born Carl Edward Migwans) made Canadian art history as the first artist of Native ancestry to have his work purchased by the National Gallery of Canada as Contemporary Art. His mother, Barbara Migwans was the Ojibwe daughter of Dominic Migwans who was then the Chief of the Ojibways of West Bay and his father, Edward Cooper, was an American soldier. He worked in various photographic mediums, mixed media, oil, acrylic, spontaneously scripted text on canvas, works on paper, Plexiglas, stone, cement, wood, and found objects, in addition to etching, lithography, and screen process.

Gallery

- Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay.jpg

Bust of Aysh-ke-bah-ke-ko-zhay (Eshkibagikoonzhe or "Flat Mouth"), a Leech Lake Ojibwa chief

- Nanongabe.jpg

Chief Beautifying Bird (Nenaa'angebi), by Benjamin Armstrong, 1891

- Be sheekee.jpg

Bust of Beshekee, war chief, modeled 1855, carved 1856

- Squawandchild.jpg

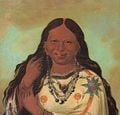

Ojibwa woman and child, painted by Charles Bird King

- Tshusick.jpg

Tshusick, an Ojibwa woman, painted by Charles Bird King

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Danziger, E. J., Jr. 1978. The Chippewa of Lake Superior. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Grim, J. A. 1983. The shaman: Patterns of religious healing among the Ojibway Indians. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Gross, L. W. 2002. The comic vision of Anishinaabe culture and religion. American Indian Quarterly 26: 436-459.

- Blessing, Fred K., Jr. 1977. The Ojibway Indians Observed. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Archaeological Society.

- Barnouw, Victor. 1977. Wisconsin Chippewa Myths and Tales and Their Relation to Chippewa Life. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Hoffman, Walter James. 2005. The Mide'wiwin: Grand Medicine Society of the Ojibway. University Press of the Pacific. ISBN 1410222969

- Vizenor, Gerald. 1984. The People Named the Chippewa: Narrative Histories. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0816613052

- Johnston, Basil. [1987] 1990. Ojibway Ceremonies. Bison Books. ISBN 0803275730

- Johnston, Basil. [1976] 1990.Ojibway Heritage. Bison Books. ISBN 0803275722

- Johnston, Basil. [1995] 2001. The Manitous: The Spiritual World of the Ojibway. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0873514114

- Andrews, Terri J. 1997. Living By The Dream. The Turquoise Butterfly Press. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- William Jones. [1917] 2007. Ojibwa Texts. Retrieved October 30, 2008. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0548575925

- Densmore, Frances. [1929, 1979] 2008. Chippewa Customs. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1436683241

- Densmore, Frances. 2006. Chippewa Music. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1425499563

- Johnston, Basil. 1990. Ojibway Ceremonies. Bison Books. ISBN 0803275730

- Warren, William W. [1851] 1984. History of the Ojibway People. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 087351162X

- Roy, Loriene. 2008. Ojibwa. Multicultural America. Retrieved October 29, 2008.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Johnston, Basil H. 2007. Anishinaubae Thesaurus. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 978-0870137532

- Erdrich, Louise. 2003. Books and Islands in Ojibwe Country. National Geographic. ISBN 0792257197

- Tanner, John. [1830] 2007. A Narrative Of The Captivity And Adventures Of John Tanner, U. S. Interpreter At The Saut De Ste. Marie During Thirty Years Residence Among The Indians In The Interior Of North America. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0548213131

- Cubie, Doreen. 2007. Restoring a Lost Legacy. National Wildlife 45(4): 39-45. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- BBC News. 2005. Teenage gunman kills nine in US BBC. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- Schneider, Karoline. 2003. The Culture and Language of the Minnesota Ojibwe: An Introduction. Kee's Ojibwe page. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- Sultzman, Lee. 2000. Ojibwe History. First Nations Histories. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- Hodge, Frederick Webb. [1912] 2003. Chippewa. Handbook of American Indians North of Mexico. Digital Scanning Inc. Retrieved October 30, 2008. ISBN 1582187487

- Hlady, Walter M. 1961. Indian Migrations in Manitoba and the West. Manitoba Historical Society Transactions, Series 3. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

External links

- Text to the "Ojibwe Prayer to a Slain Deer"

- Freelang Ojibwe Dictionary, an extensive electronic Ojibwe-English/English-Ojibwe language dictionary

- An Introduction to Ojibway Culture and History

- Ojibwe Song Pictures, recorded by Frances Desmore

- The Making of an Ojibwe Hand Drum video

- First Nations of Minnesota: Anishinabe Minnesota State University, Mankato.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.