Niagara Falls

Niagara Falls is a set of massive waterfalls located on the Niagara River in eastern North America, on the border between the United States and Canada. Three separate waterfalls constitute Niagara Falls: the Horseshoe Falls (Canadian Falls), the American Falls, and the smaller, adjacent Bridal Veil Falls. The falls are located 16 miles from the U.S. city of Buffalo and 43 miles from the Canadian city of Toronto. The falls formed after the receding of the glaciers of the most recent Ice Age, as water from the newly formed Great Lakes carved a path through the Niagara Escarpment en route to the Atlantic Ocean. While not exceptionally high, the Niagara Falls are very wide. With more than six-million cubic feet of water falling over the crestline every minute in high flow, and almost four million cubic feet on average, they constitute the most powerful waterfall in North America.[1]

Not renowned only for their beauty, the falls are a valuable source of hydroelectric power for both Ontario and New York. Preserving this natural wonder from commercial overdevelopment while allowing for the needs of the area's people has been a challenging project for environmental preservationists since the nineteenth century. A popular tourist site for over a century, the falls are shared by the twin cities of Niagara Falls, Ontario and Niagara Falls, New York. Some 20 million visitors are expected to visit the falls in 2007, with the annual rate increasing in 2009 to over 28 million tourists a year.

Formation

The historical roots of Niagara Falls lie in the Wisconsin glaciation, which ended around tren thousand years ago. The North American Great Lakes and the Niagara River are effects of this last continental ice sheet, an enormous glacier that crept across the area from eastern Canada. The glacier drove through the area like a giant bulldozer, grinding up rocks and soil, moving them around, and deepening some river channels to make lakes. It dammed others with debris, forcing these rivers to make new channels.[2] It is thought that there is an old valley, buried by glacial drift, at the approximate location of the present Welland Canal.

After the ice melted, drainage from the upper Great Lakes became the present-day Niagara River, which could not follow the old filled valley, so it found the lowest outlet on the rearranged topography. In time the river cut a gorge across the Niagara Escarpment, the north facing cliff or cuesta formed by erosion of the southwardly dipping (tilted) and resistant Lockport formation between Lake Erie and Lake Ontario. In doing so it exposed old marine rocks that are much older than the geologically recent glaciation. Three major formations are exposed in the gorge that was cut by the Niagara River.

When the newly established river encountered the erosion-resistant Lockport dolostone, the hard layer eroded much more slowly than the underlying softer rocks. The aerial photo clearly shows the hard caprock, the Lockport Formation (Middle Silurian), which underlies the rapids above the falls and approximately the upper third of the high gorge wall. It is composed of very dense, hard, and very strong limestone and dolostone.

Immediately below, comprising about two thirds of the cliff, is the weaker, softer, and more crumbly and sloping Rochester Formation (Lower Silurian). It is mainly shale, though it has some thin limestone layers, and contains large quantities of fossils. Because it erodes more easily, the river has undercut the hard cap rock and created the falls.

Submerged in the river in the lower valley, hidden from view, is the Queenston Formation (Upper Ordovician), which is composed of shales and fine sandstones. All three formations were laid down in an ancient sea, and their differences of character derive from changing conditions within that sea.

The original Niagara Falls were near the sites of present-day [[Queenston, Ontario, Canada, and Lewiston, New York, but erosion of their crest has caused the waterfalls to retreat several miles southward. Just upstream from the Falls' current location, Goat Island splits the course of the Niagara River, resulting in the separation of the Canadian Horseshoe Falls to the west from the American and Bridal Veil Falls to the east. Although erosion and recession have been slowed in this century by engineering, the falls will eventually recede far enough to drain most of Lake Erie, the bottom of which is higher than the bottom of the falls. Engineers are working to reduce the rate of erosion to retard this event as long as possible.

The Canadian Horseshoe Falls drop about 170 feet, although the American Falls have a clear drop of only 70 feet before reaching a jumble of fallen rocks which were deposited by a massive rock slide in 1954. The larger Canadian Horseshoe Falls are about 2,600 feet wide, while the American Falls are 1,060 feet wide. The volume of water approaching the Falls during peak flow season is 202,000 cubic feet per second.[3] By comparison Africa's spectacular Victoria Falls has over 19 million cubic feet of water falling over its crestline each minute in the wet season, and spray from this rises several hundreds of feet into the air because of the incredible force of the falling water.

During the summer months, when maximum diversion of water for hydroelectric power occurs, 100,000 cubic feet per second of water actually traverses the falls, some ninety percent of which goes over the Horseshoe Falls. This volume is further halved at night, when most of the diversion to hydroelectric facilities occurs.

Historical background

Native American legend

The region's original inhabitants were the Ongiara, an Iroquois tribe named the Neutrals by French settlers, who found them helpful in mediating disputes with other tribes. The name "Niagara" is said to originate from an Iroquois word "Onguiaahra" meaning "The Strait."

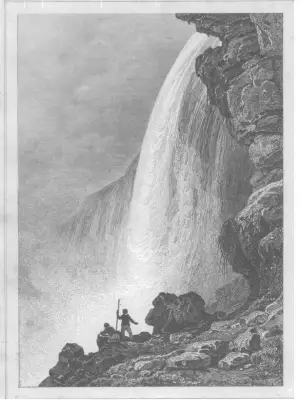

Native American legend tells of Lelawala, a beautiful maid betrothed by her father to a brave she despised. Rather than marry, Lelawala chose to sacrifice herself to her true love He-No, the Thunder God, who dwelt in a cave behind the Horseshoe Falls. She paddled her canoe into the swift current of the Niagara River and was swept over the brink. He-No caught her as she plummeted, and together their spirits are said to live forever in the Thunder God's sanctuary behind the Falls.

European discovery

Some controversy exists over which European first gave a written, eyewitness description of the falls. The area was visited by French explorer Samuel de Champlain as early as 1604 during his exploration of Canada. Members of his party reported to him on the spectacular waterfalls, which he wrote of in his journals but may never have actually visited. Some credit Finnish-Swedish naturalist Pehr Kalm with the original firsthand description, penned during an expedition to the area early in the eighteenth century. Most historians however agree that Belgian Father Louis Hennepin observed and described the falls much earlier, in 1677, after traveling in the region with explorer René Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, thus bringing them to the world's attention. Hennepin also first described the Saint Anthony Falls in Minnesota. His subsequently discredited claim that he also traveled the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico cast some doubt on the validity of his writings and sketches of Niagara Falls.

There is credible evidence, however, that Reverend Paul Ragueneau (1608–1680) visited the falls prior to Hennepin's claim. Ragueneau was a French Jesuit who was working among the Huron First Nation in Canada. Born in Paris, Father Ragueneau entered the Society of Jesus about 1626 at the age of 18 and wrote more about his work than any other Jesuit in Canada. Ragueneau described the natural wonder in his writings some 35 years before Hennepin's visit.

Early tourism

During the eighteenth century, tourism became popular; it was the area's main industry by mid-century. Napoleon Bonaparte's brother Jérôme visited with his bride in the early nineteenth century.[4]

Demand for passage over the Niagara River led in 1848 to the building of a footbridge and then Charles Ellet's Niagara Suspension Bridge. This was supplanted by German-born John Augustus Roebling's Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge in 1855.

After the American Civil War, the New York Central railroad publicized Niagara Falls as a focus of pleasure and honeymoon visits. With increased railroad traffic, in 1886 Leffert Buck replaced Roebling's wood and stone bridge with the predominantly steel bridge that still carries trains over the Niagara River today. The first steel archway bridge near the falls was completed in 1897. Known today as the Whirlpool Rapids Bridge, it carries vehicles, trains, and pedestrians between Canada (through Canadian Customs Border Control) and the U.S. just below the falls. In 1941 the Niagara Falls Bridge Commission completed the third current crossing in the immediate area of Niagara Falls with the Rainbow Bridge, carrying both pedestrian and vehicular traffic between the two countries and Canadian and U.S. customs for each country.

Especially after the First World War, tourism boomed again as automobiles made getting to the falls much easier. The story of Niagara Falls in the twentieth century is largely that of efforts to harness the energy of the falls for hydroelectric power and to control the rampant development on both the American and Canadian sides which threatened the area's natural beauty.

Impact on industry and commerce

Hydoelectric power

The enormous energy of the falls was long recognized as a potential source of power. The first known effort to harness the waters was in 1759, when Daniel Joncairs built a small canal above the Falls to power his sawmill. Augustus and Peter Porter purchased this area and all of American Falls in 1805 from the New York state government, and enlarged the original canal to provide hydraulic power for their gristmill and tannery. In 1853, the Niagara Falls Hydraulic Power and Mining Company was chartered, which eventually constructed the canals which would be used to generate electricity. In 1881, under the leadership of Jacob Schoellkopf, enough power was produced to send direct current to illuminate both the Falls themselves and nearby Niagara Falls village.

When Nikola Tesla, for whom a memorial was later built at Niagara Falls, N.Y., invented the three-phase system of alternating current power transmission, distant transfer of electricity became possible. In 1883, the Niagara Falls Power Company, a descendant of Schoellkopf's firm, hired George Westinghouse to design a system to generate alternating current. By 1896, with financing from moguls like J. P. Morgan, John Jacob Astor IV, and the Vanderbilts, they had constructed giant underground conduits leading to turbines generating upwards of 100,000 horsepower, and were sending power as far as Buffalo, twenty miles away.

Private companies on the Canadian side also began to harness the energy of the falls. The Government of the province of Ontario, Canada eventually brought power transmission operations under public control in 1906, distributing Niagara's energy to various parts of the Canadian province. Currently between 50 percent and 75 percent of the Niagara River's flow is diverted via four huge tunnels that arise far upstream from the waterfalls. The water then passes through hydroelectric turbines that supply power to nearby areas of the Canada and the U.S. before returning to the river well past the falls.

The most powerful hydroelectric stations on the Niagara River are Sir Adam Beck 1 and 2 on the Canadian side, and the Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant and the Lewiston Pump Generating Plant on the American side. All together, Niagara's generating stations can produce about 4.4 GW of power.

In August 2005, Ontario Power Generation, which is now responsible for the Sir Adam Beck stations, announced plans to build a new six and a half-mile tunnel to tap water from farther up the Niagara River than is possible with the existing arrangement. The project is expected to be completed in 2009, and will increase Sir Adam Beck's output by about 182 megawatts (4.2 percent).

Commerce

Ships can bypass Niagara Falls by means of the Welland Canal, which in the 1960s was improved and incorporated into the Saint Lawrence Seaway. While the seaway diverted water traffic from nearby Buffalo and led to the demise of its steel and grain mills, other industries in the Niagara River valley flourished until the 1970s with the help of the electric power produced by the river. Since then the region has declined economically.

The cities of Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada and Niagara Falls, New York, USA are connected by three bridges, including the Rainbow Bridge, just downriver from the falls, which affords the closest view of the falls and is open to non-commercial vehicle traffic and pedestrians. The Whirlpool Rapids Bridge, one mile down from the Rainbow bridge and the oldest bridge over the Niagara River is open only to NEXUS Pass holders a limited amount of hours. The newest bridge, the Lewiston-Queenston Bridge, is located near the escarpment.

Preservation efforts

For the first two centuries after European settlement of the area, land on both sides of Niagara Falls was privately owned. Development and commercial ventures threatened the natural beauty of the area, and visitors sometimes had to pay entrepreneurs a fee to view the falls through holes in a fence. Public dissatisfaction led to the Free Niagara movement, which included the artist Frederick Church, the landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, New York Assemblyman Thomas Vincent Welch, and the journalist Jonathan Baxter Harrison. A series of Harrison's letters to newspapers in Boston and New York (collected in the 1882 pamphlet The Condition of Niagara Falls, and the Measures Needed to Preserve Them) were particularly influential in turning public opinion in favor of preservation.[5]

In 1885, the state of New York began to purchase land from developers, under the charter of the Niagara Reservation State Park. In the same year, the province of Ontario in Canada established the Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Park for the same purpose. Both organizations have proved remarkably successful operations that have restricted development on both sides of the Falls and the Niagara River. On the Canadian side, the Niagara Parks Commission governs land usage along the entire course of the Niagara River, from Lake Erie to Lake Ontario.

Until the modern era, the falls were receding southward owing to erosion from two to ten feet per year. This process was slowed initially by diversion of increasing amounts of flow from the Niagara River into hydroelectric plants in both the United States and Canada. On January 2, 1929, Canada and the United States reached an agreement on an action plan to preserve the falls. In 1950, the two countries signed the Niagara River Water Diversion Treaty, which more specifically addressed the issue of water diversion.

In addition to the effects of diversion of water to the power stations, erosion control efforts have included underwater weirs to redirect the most damaging currents, and actual mechanical strengthening of the top of the Falls. The most dramatic such work was performed in 1969. In June of that year, the Niagara River was completely diverted away from the American Falls for several months through the building of a temporary rock and earth dam (clearly visible in the photo at right), effectively shutting off the American Falls.[6]

While the Horseshoe Falls absorbed the extra flow, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers studied the riverbed and mechanically bolted faults which would otherwise have hastened the retreat of the American Falls. A plan to remove the huge mound of talus deposited in 1954 was abandoned owing to cost, and in November 1969, the temporary dam was dynamited, restoring flow to the American Falls. Even after these undertakings, Luna Island, the small piece of land between the main waterfall and the Bridal Veil, remained off limits to the public for years owing to fears that it was unstable and could collapse into the gorge at any time.

Preservation efforts have extended beyond and above the falls themselves. Recent construction of several tall buildings (most of them hotels) on the Canadian side has caused the airflow over the falls to change direction. Students at the University of Guelph demonstrated, using scale models, that the air passes over the top of the new hotels, causing a breeze to roll down the south sides of the buildings and spill into the gorge below the falls, where it feeds into a whirlpool of moisture and air. The result is that the viewing areas on the Canadian side are now often obscured by a layer of mist.[7]

Over The Falls

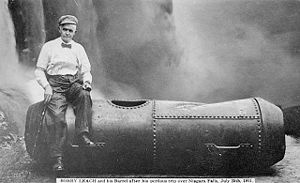

In October 1829, Sam Patch, who called himself The Yankee Leaper, jumped over the Horseshoe Falls and became the first known person to survive the plunge. This began a long tradition of daredevils trying to go over the falls and survive. In 1901 63-year-old Annie Edson Taylor was the first person to go over the falls in a barrel; she survived virtually unharmed. Soon after exiting the barrel, she said, "No one should ever try that again." Since Taylor's historic ride, 14 other people have intentionally gone over the falls in or on a device, despite her advice. Some have survived unharmed, but others have drowned or been severely injured. Survivors of such stunts face charges and stiff fines, as it is illegal, on both sides of the border, to attempt to go over the falls.

Other daredevils have made crossing the falls their goal, starting with the successful passage by Jean François "Blondin" Gravelet in 1859. These tightrope walkers drew huge crowds to witness their exploits. Their wires ran across the gorge, near the current Rainbow Bridge, not over the waterfall itself. Among the many was Ontario's William Hunt, who billed himself as "Signor Fanini" and competed with Blondin in performing outrageous stunts over the gorge. Englishman Captain Matthew Webb, the first man to swim the English Channel, drowned in 1883 after unsuccessfully trying to swim across the whirlpools and rapids downriver from the falls with nine other people. Two others drowned with him, and the other seven gave up before finishing their course.

In what some called the "Miracle at Niagara," Roger Woodward, a seven-year-old American boy, was swept over the Horseshoe Falls protected only by a life vest on July 9, 1960, as two tourists pulled his 17-year-old sister Deanne from the river only 20 feet from the lip of the Horseshoe Falls at Goat Island. Minutes later, Roger was plucked from the roiling plunge pool beneath the Horseshoe Falls after grabbing a life ring thrown to him by the crew of the Maid of the Mist boat. His survival, which no one thought possible, made news throughout the world.

On July 2, 1984, Canadian Karel Soucek from Hamilton, Ontario successfully plunged over the Horseshoe Falls in a barrel with only minor injuries. Soucek was fined $500 for performing the stunt without a license. In 1985, he was killed while attempting to re-create the stunt at the Houston Astrodome by climbing into a barrel and dropping 180 feet into a water tank in front of 45,000 people; his barrel hit the side of the tank.

In August 1985, Steve Trotter, age 22, an aspiring stuntman from Rhode Island, became the youngest person ever and the first American in 25 years to go over the falls in a barrel. Ten years later, Trotter went over the falls again, becoming the second person to go over the falls twice and survive. It was also the second-ever "duo;" Lori Martin joined Trotter for the barrel ride over the falls. The first two-person trip over the brink goes to Jeffrey Petkovich, 25, and Peter Debernardi, 42, on September 27, 1989.

Kirk Jones of Canton, Michigan, became the first known person to survive a plunge over the Horseshoe Falls without a flotation device on October 20, 2003. While it is still not known whether Jones was determined to commit suicide, he survived the 16-story fall with only battered ribs, scrapes, and bruises.

No human has ever survived a plunge over the American Falls, owing to the many boulders and the relatively weak current. All survivors and daredevils have passed over the Horseshoe Falls, where there are fewer boulders and the current can "throw" a person farther away from the brink and (hopefully) avoid the boulders.

Tourism

Peak numbers of visitors occur in the summertime, when Niagara Falls are both a daytime and evening attraction. From the Canadian side, floodlights illuminate both sides of the falls for several hours after dark (until midnight). The number of visitors in 2007 is expected to total 20 million and by 2009, the annual rate is expected to top 28 million tourists a year.

From the American side, the American Falls can be viewed from walkways along Prospect Park, which also features an observation tower. Nearby, the Cave of the Winds trail leads hikers down some three hundred steps to a point beneath Bridal Veil Falls. The Niagara Scenic Trolley offers guided trips along the American Falls. On the American side, stunning panoramic and aerial views of the falls can be viewed from the top floor of Frank Parlato Jr.'s One Niagara/Niagara Center (called "The greatest view in the world"), "The Flight of Angels" hot air balloon ride or by helicopter.

On the Canadian side, Queen Victoria Park features manicured gardens, platforms offering spectacular views of both the American and Horseshoe Falls, and underground walkways leading into observation rooms which yield the illusion of being within the falling waters. The observation deck of the nearby Skylon Tower offers the highest overhead view of the falls, and in the opposite direction gives views as far as distant Toronto.[8] Along with the Minolta Tower (formerly the Konica Minolta Tower), it is one of two towers in Canada with a view of the falls.

Along the Niagara River, the Niagara River Recreational Trail runs the 35 miles from Fort Erie to Fort George, and includes many historical sites from the War of 1812.

The Maid of the Mist cruises, named for an ancient Ongiara Indian mythical character, have carried passengers into the whirlpools beneath the Falls since 1846. The Whirlpool Aero Car, built in 1916 from a design by Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo, is a cable car which takes passengers over the whirlpool on the Canadian side. The Journey Behind the Falls—accessible by elevators from the street level entrance—consists of an observation platform and series of tunnels near the bottom of the Horseshoe Falls on the Canadian side.

Notes

- ↑ Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada. Niagaraparks.com.

- ↑ Niagara Falls Geological History. Info Niagara: Niagara Falls Tourist Information Guide. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Berketa, Rick. Niagara Falls History of Power. Niagara Falls Thunder Alley. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Izon, Lucy. Niagara Falls was where Napoleon's brother chose to honeymoon. www.canadacool.com. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ↑ Chronology of the American Conservation Movement, 1847-1920. Library of Congress. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ↑ This effect also obtained once as a result of natural forces, as an upstream ice jam stopped almost all water flow over Niagara Falls on March 29, 1848.

- ↑ Discovery Channel Video Player. DiscoverChannel.ca. Retrieved April 19, 2007.

- ↑ Let's Go Travel Guide, 2004.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grant, John. Niagara Falls: An Intimate Portrait. Pequot, 2006. ISBN 978-0762740253

- Mason, Charles. Anthology and Bibliography of Niagara Falls (2 volumes). J.B. Lyons Corp., 1921. ASIN B000ELOL5U

- Tammemagi, Hans. Exploring Niagara: The Complete Guide to Niagara Falls and Vicinity. Fitzhenry and Whiteside, 2007. ISBN 978-1550418330

- Wilt, Dirk Vander. Niagara Falls: A Guide for Tourists. Parkscape Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0976706410

External links

All links retrieved November 14, 2022.

- Niagara Falls State Park. www.niagarafallsstatepark.com.

- Niagara Falls—History of Power. www.niagarafrontier.com.

- Niagara’s Fury. www.niagaraparks.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.