Difference between revisions of "Messiah" - New World Encyclopedia

(various corrections) |

(approved) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Contracted}} | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Contracted}} |

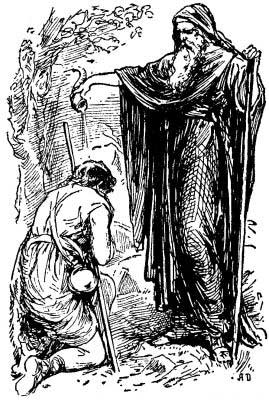

[[Image:Samuel-Anoints-David.jpg|thumb|400px|Samuel anoints David as Israel's future king.]] | [[Image:Samuel-Anoints-David.jpg|thumb|400px|Samuel anoints David as Israel's future king.]] | ||

The term '''Messiah''', literally "anointed one", refers to the belief in a religious (and often political) savior figure who inaugurates a new age and overthrows the old world order. In Judaism, a messiah (in Hebrew: {{unicode|Mašíach}}='''מָשִׁיחַ''') originally meant any person anointed by a prophet or priest of God, especially a [[David]]ic king. In English today, the word Messiah can denote any person who is regarded as a savior or liberator, although the term is most commonly used to refer to Jesus of Nazareth, who is considered by many to be the anticipated savior of the Jews and humankind. Indeed, the word ''[[Christ]]'' (Χριστός, ''Christos'', in Greek) is a literal translation of the Hebrew ''mashiach'', or "anointed one". | The term '''Messiah''', literally "anointed one", refers to the belief in a religious (and often political) savior figure who inaugurates a new age and overthrows the old world order. In Judaism, a messiah (in Hebrew: {{unicode|Mašíach}}='''מָשִׁיחַ''') originally meant any person anointed by a prophet or priest of God, especially a [[David]]ic king. In English today, the word Messiah can denote any person who is regarded as a savior or liberator, although the term is most commonly used to refer to Jesus of Nazareth, who is considered by many to be the anticipated savior of the Jews and humankind. Indeed, the word ''[[Christ]]'' (Χριστός, ''Christos'', in Greek) is a literal translation of the Hebrew ''mashiach'', or "anointed one". | ||

Revision as of 07:58, 29 July 2006

The term Messiah, literally "anointed one", refers to the belief in a religious (and often political) savior figure who inaugurates a new age and overthrows the old world order. In Judaism, a messiah (in Hebrew: Mašíach=מָשִׁיחַ) originally meant any person anointed by a prophet or priest of God, especially a Davidic king. In English today, the word Messiah can denote any person who is regarded as a savior or liberator, although the term is most commonly used to refer to Jesus of Nazareth, who is considered by many to be the anticipated savior of the Jews and humankind. Indeed, the word Christ (Χριστός, Christos, in Greek) is a literal translation of the Hebrew mashiach, or "anointed one".

The concept of Messiah is prevalent in several world religions as well as new religious movements. In Islam, Jesus (Isa) is considered to be the Masih, or Messiah, and his eventual return to the Earth is expected along with that of another messianic figure, the Mahdi. In many forms of Buddhism, Maitreya Buddha is expected to return as a Messiah figure. Bahá'u'lláh (1817-1892), claimed to be the promised one of all religions, and founded the Bahá'í Faith. In the Unification Church, Reverend Sun Myung Moon is considered to be the Messiah along with his wife. (This distinct coupling of the male and female aspects is unique in most conceptions of Messiah.)

History

Some scholars believe that the concept of the Messiah arose during the Babylonian exile (c. 597-538 or c. 586-538 B.C.E.) of the Jews when the Jewish concept of a Davidic deliverer was fused with the Zoroastrian idea of the Saoshyant — a teacher who would lead the righteous in the cosmic struggle against evil. The concept of the Messiah developed gradually from early Jewish prophetic times through their exile in Babylon, taking more definite form in the post-exilic period. By the first century B.C.E., Jews interpreted the their scriptures to refer specifically to someone appointed by God to deliver them from oppression under the Romans. Christians came to see the scriptures as referring to a spiritual savior, rather than a worldly political savior, specifically identifying Jesus as that Messiah.

In the Hebrew Bible

The Jewish scriptures contain a number of prophecies concerning a future descendant of King David who will be anointed as the Jewish people's new leader. This section traces the development of the concept of the Messiah in the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament.

Pre-exilic references

One of the earliest of the messianic prophecies was written in the eighth century B.C.E. by the prophet Isaiah, who hoped for a more powerful and righteous ruler than the current occupant of David's throne. It refers to the coming of a new Davidic king who will unite Israel and Judah, conquer the surrounding nations, and enable the return of the Israelites taken into captivity in the Assyrian Empire:

- In that day the Root of Jesse [David's father] will stand as a banner for the peoples; the nations will rally to him, and his place of rest will be glorious. In that day the Lord will reach out his hand a second time to reclaim the remnant that is left of his people from Assyria... Ephraim's jealousy will vanish, and Judah's enemies will be cut off; Ephraim [Israel] will not be jealous of Judah, nor Judah hostile toward Ephraim. They will swoop down on the slopes of Philistia to the west; together they will plunder the people to the east. They will lay hands on Edom and Moab, and the Ammonites will be subject to them. (Isa. 11:10-14)

The prophet Jeremiah, who lived roughly a century later than Isaiah but still during a time when Davidic kings occupied the throne, echoed Isaiah's prediction:

- "The days are coming," declares the Lord, "when I will raise up to David a righteous Branch, a King who will reign wisely and do what is just and right in the land. In his days Judah will be saved and Israel will live in safety. This is the name by which he will be called: The Lord [is] Our Righteousness." (Jer. 23:5-6)

Thus, the earliest messianic references, written when Davidic kings still ruled in Judah, look forward to a wise and righteous king arising from David's lineage, a militarily powerful leader who will bring back the citizens of Israel taken captive by Assyria and unite the divided kingdoms of Israel and Judah in triumph over their regional enemies.

Exilic references

The prophet Ezekiel, originally a citizen of Judah but writing from exile in Babylon after the dissolution of the Davidic monarchy, was the first to speak of the Messiah in terms of the restoration of the Davidic line:

- I will save my flock, and they will no longer be plundered. I will judge between one sheep and another. I will place over them one shepherd, my servant David, and he will tend them; he will tend them and be their shepherd. I the Lord will be their God, and my servant David will be prince among them. I the Lord have spoken. (Ezek. 34:22-24)

Interestingly, one of the first uses of the actual term "Messiah" as the savior-liberator of Israel refers to a gentile king: Cyrus of Persia. This prophecy — belonging to "Second Isaiah" and thought have been included in the Book of Isaiah during the Babylonian exile — portrays Cyrus as a ruler anointed by God to bring the Jews back to their homeland and facilitate the rebuilding of the Temple of Jerusalem:

- I am the Lord... who says of Cyrus, "He is my shepherd and will accomplish all that I please; he will say of Jerusalem, 'Let it be rebuilt,' and of the temple, 'Let its foundations be laid.'" This is what the Lord says to his anointed [italics added], to Cyrus, whose right hand I take hold of..." (Isa. 44:24-45:1)

The Book of Isaiah's later prophecies envision a ruler of divine might and wisdom who would not only make Israel/Judah into a powerful regional empire, but even a world power:

- Nations will come to your light, and kings to the brightness of your dawn. Lift up your eyes and look about you: All assemble and come to you; your sons come from afar, and your daughters are carried on the arm. Then you will look and be radiant, your heart will throb and swell with joy; the wealth on the seas will be brought to you, to you the riches of the nations will come. (Isa. 60:3-5)

The reign of the Messiah would not only bring peace and properity to the Jews, but tremendous benefits to mankind, even restoring the original edenic nature in which humans live for centuries and animals are no longer predatory.

- "Never again will there be... an infant who lives but a few days, or an old man who does not live out his years; he who dies at a hundred will be thought a mere youth... The wolf and the lamb will feed together, and the lion will eat straw like the ox, but dust will be the serpent's food. They will neither harm nor destroy on all my holy mountain," says the Lord. (Isa. 65:20-25)

Thus, the concept of the Messiah developed from the idea of a righteous Davidic king who would unite Israel and Judah and conquer their enemies, to a cosmic Prince of Peace who would restore the world into a virtual Garden of Eden. Some scholars believe the Zoroastrian idea of the "Saoshyant" — a leader who will spread divine truth and lead humanity in the final battle against the forces of evil — influenced the messianic ideas of the Babylonian Jews returning from exile.

It is not possible to say with certainty how widespread or intense the messianic hope had become among the Jews in this period (please give dates). Generally, those who were taken into exile were the urban elites, while those who made the return trip back to Jerusalem two generations later were likely to be those who had been most deeply influenced by the hope of restoring Jerusalem and its Temple to their former glory. Those residents of Judah and Israel and their descendants who did not make the trip to Babylon probably remained largely unaffected by the above developments in messianic thought until later, as the mature form the the Jewish religion took deeper roots among the populace.

Post-exilic references

Like the Book of Isaiah, the post-exilic prophets Haggai and Zechariah name a specific messianic candidate. They indicate that Jerusalem's governor, Zerubbabel, a grandson of King Jehoiachin who returned to Jerusalem under Cyrus' sponsorship, may in fact be the Davidic "branch":

- "I will take you, my servant Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel," declares the Lord, "and I will make you like my signet ring, for I have chosen you." (Hag. 2:23)... "What are you, O mighty mountain? Before Zerubbabel you will become level ground. Then he will bring out the capstone to shouts of 'God bless it! God bless it!'" (Zech. 4:7)

These prophets' expectations in Zerubbabel apparently were not completely realized, for although the Temple itself was rebuilt, the dream of his ruling with God's royal authority did not come true. Indeed, no Davidic descendant was ever to occupy the throne again. Several of Zechariah's messianic predictions, however, became important in later years. It was his prophecy which Jesus attempted to fulfill in his "triumphal entry" into Jerusalem (see below). Zechariah also predicted the coming of two "anointed ones," interpreted by the Essenes and others to be a priestly Messiah (a son of Aaron) and a kingly Messiah (son of David):

- Then I asked the angel, "What are these two olive trees on the right and the left of the lampstand?"... So he said, "These are the two who are anointed to serve the Lord of all the earth." (Zech. 4:11-14)

Zechariah and other prophets also reported a number of apocalyptic visions, continuing a trend begun by Ezekiel that increasingly excited the imagination of the people during this period in connection with the coming of the messianic "Day of the Lord." The Book of Daniel, with its vision of a supernatural "son of man" — though not included among the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible and considered by most scholars to have been written considerably later — became an important influence on second and first century B.C.E. Jews:

- In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all peoples, nations and men of every language worshiped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom is one that will never be destroyed. (Dan. 7:13-14)

Inter-testamental developments

In the period between the writing of the last of the prophetic books and the first century B.C.E., the concept of the Messiah developed considerably, as did the Jewish people's hope in the coming of an anointed deliverer.

The ideals of the books of Isaiah, emphasizing the Messiah as a Prince of Peace and a deliverer of Israel from oppression, represented one strain of thought. Apocalyptic promises of supernatural intervention by prophets such as Zechariah, Joel, and others represented a more other-worldly trend. The apocryphal Book of Enoch, though of disputed authorship and never accepted into the Jewish canon, further demonstrates the apocalyptic trend in Jewish messianic thought. At the same time, it should be remembered that in this period, the scriptures were still read as individual books, not as a collection. The idea of the Messiah does not exist in many of the Biblical books, and faith in the coming of a Messiah was neither uniform nor universal. In terms of intertestamental literature (the Old Testament Apocrypha), the Jewish Encyclopedia points out that "Ecclesiasticus, Judith, Tobit, Baruch, II Maccabees, and the Wisdom of Solomon contain no mention of the Davidic hope."

Reportedly, some Jews saw the Greek ruler Alexander the Great as a messianic figure. The Book of Daniel, on the other hand, has been interpreted by scholars as an anti-Greek tract encouraging Jews to resist the desecration of the Temple by the later Greek ruler Anitiochus Epiphanes. In that context, the successful rebellion of Judah Maccabee was a quasi-messianic event, but hope in the restoration of a glorious Jewish kingdom faded as Judah's Hasmonean successors fell into corruption and collaboration with Roman gentile rulers.

In the first century B.C.E., the Qumran sect reacted against the corruption of both priestly and political authorities, foreseeing the imminent coming of the Day of the Lord in which both an Aaronic and a Davidic Messiah should arise to lead the "children of light" in battle against the gentiles and other "children of darkness." Some among the emerging sect of the Pharisees, meanwhile, hoped in the Messiah as a deliverer along the lines of the Book of Isaiah. Others expected cataclysmic events such as described in the Book of Daniel, I Enoch, and other apocalyptic literature. The Zealots, meanwhile, thought of the Messiah in more strictly military/political terms, believing that whatever God's role in his coming might be, it was incumbent on human beings to resist evil rulers, with violence if necessary.

Such were the messianic hopes that flourished just prior to, during, and after the reign of Herod the Great (37-4 B.C.E.). Ever vigilant against possible threats to his throne, Herod slaughtered 45 members of the Sanhedrin — mostly Sadducees — that had supported the Hasmonean rebel Antigonus, seen by many Jews as a messianic forerunner. Later, Herod put to death several leading Pharisees who declared that the imminent birth of the Messiah would signal the end of Herod's reign. In Christian tradition, Herod also slaughtered the infant boys of Bethlehem in fear that one of them was the Messiah.

The most famous of the several known messianic candidates of the era (see list below), of course, was Jesus of Nazareth. Early rabbinic Judaism continued to develop its ideas of the Messiah in a dialectical and often bitter relationship with the Christians, who sought to prove that the resurrected Jesus was in fact God's anointed one.

After the first century Jewish rebellion against Rome, which led to the destruction of the Temple and the expulsion of the Jews from Jerusalem in 70 C.E., Jewish messianism lived on as Jews hoped desperately, if in vain, for a deliverer from Roman oppression. Another famous messianic claimant was Simon Bar Kochba, who gained the support of the famous Talmudic rabbi Akiva and succeeded in establishing a state independent of Roman rule from approximately 132-135 c.e.. His rebellion was eventually crushed at a cost estimated to be as high as half a million Jewish lives. From then on, rabbinic Judaism looked with suspicion on any specific messianic candidate, while still promoting general hope in the future coming of the Messiah.

Jesus as the Messiah

Christianity emerged in the first century C.E. as a movement among Jews who believed Jesus of Nazareth to be the Messiah. The very name, "Christian," refers to the Greek word for "Messiah" (Kristos). Although Christians commonly refer to Jesus as "Christ" rather than "Messiah," the two words are synonymous. According to the New Testament, the disciples believed that Jesus was the very Messiah that Jews were expecting. John 1:41-42 says:

- The first thing Andrew did was to find his brother Simon and tell him, "We have found the Messiah" (that is, the Christ). And he brought him to Jesus.

Scholars today debate whether Jesus actually considered himself to be the Messiah. He did not use the title as such, but referred to himself as the "son of man," a title that was also used by prophets such as Ezekiel, but could also refer to the apocalyptic figure of Daniel, or simply mean a human being, literally a "son of Adam." In the synoptic Gospels his identity as Messiah is kept secret from the public until his triumphal entry into Jerusalem a few days prior to his death. In that scene, Jesus rides into the city on a donkey to shouts of "Hosanna! Son of David!" (Mt. 21:1-9) in a purposeful fulfillment of Zechariah's messianic prophecy:

- Rejoice greatly, O Daughter of Zion! Shout, Daughter of Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you, righteous and having salvation, gentle and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey. (Zech. 9:9)

Although the Gospels reflect a later theology in which Jesus' rejection and death on the Cross are predestined by God, it is likely that during Jesus' life, his disciples thought of his mission in terms similar to the Jewish messianic concept of a political deliver and teacher of righteousness. Luke's gospel shows that after Jesus' crucifixion, the disciples were shocked and disillusioned, having no inkling that Jesus' death was part of his plan, and deeply saddened the he turned out not to be the promised deliverer:

- He asked them, "What are you discussing together as you walk along?" They stood still, their faces downcast... "About Jesus of Nazareth," they replied. "He was a prophet, powerful in word and deed before God and all the people. The chief priests and our rulers handed him over to be sentenced to death, and they crucified him; but we had hoped that he was the one who was going to redeem Israel." (Luke 24:13-21)

In the Book of Acts, Luke indicates that the disciples continued to hope that the risen Jesus would perform the role Israel's political redeemer rather than primarily a spiritual savior: "So when they met together, they asked him, 'Lord, are you at this time going to restore the kingdom to Israel?'" (Acts 1:6)

In the book of Matthew, Jesus asked Peter who he thought Jesus was, and Peter answered, "You are the Christ, the Son of the Living God." And Jesus answered, "Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jona! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven." He continued to say about Peter, "On this rock I will build my church" (Matt: 14-18). While scholars debate whether this was a later addition to the text, it is taken by Western Christianity as the source of Peter's authority of the Church that became headquartered at Vatican City in Rome.

Eventually the Christian concept of the Messiah grew into something fundamentally different from the Jewish concept. Rather than being primarily a deliverer of the people of Israel from political oppression, in Christian theology, the Christ/Messiah serves four main functions:

- He suffers and dies to make atonement before God for the sins of all humanity, without which no one can share in the resurrection.

- He serves as a living example of how God expects people to act.

- At his Second Coming, he will establish peace and rule the world for a long time.

- He is an incarnation of God, who pre-existed his human birth as the Second Person of the Holy Trinity.

(Ankerberg & Weldon, pp. 218-223)

In developing these doctrines, Christians came to interpret several passages of the Old Testament very differently from Jews. For example:

- The Servant Songs of Isaiah were interpreted not as descriptions of Israel's suffering and redemption, but as predictions of the suffering of Jesus as the Messiah.

- Isaiah's prediction of the birth of the child Immanuel as a specific sign to King Ahaz in the eighth century B.C.E. (Isa. 7), was interpreted to refer to Jesus' Virgin Birth and Incarnation.

- The "son of man" passages in the Book of Daniel were interpreted as referring to Jesus' Second Coming on the clouds of heaven.

- Similarly, the expectation that the Messiah, as the Prince of Peace, would re-establish David's Kingdom on earth was postponed to the Second Coming.

The debate between Christians and Jews about the nature of the Messiah in the first two centuries C.E. created a sharp division in the theology of these two groups, so much so that many synagogues expelled Jews who affirmed Jesus, and Christian bishops forbade their congregations to have anything to do with Jews. Christians exalted their Messiah to the status of a divinity, while Jews considered such ideas blasphemous, rejecting messianic apocalypticism to affirm that Messiah, though an agent of God, was in essence no different from other humans.

Later Jewish Views

Rabbinic thought about the Messiah as expressed in the Talmud varies significantly, as the Talmud presents numerous debates and conflicting opinions of the early rabbis. The most authoritative Jewish understanding of the Messiah can be found in the writings of medieval Jewish sage Maimonides. In the Mishneh Torah, his 14-volume compendium of Jewish law, Maimonides writes:

- "The anointed King is destined to stand up and restore the Davidic Kingdom to its antiquity, to the first sovereignty. He will build the Temple in Jerusalem and gather the strayed ones of Israel together... Whoever does not believe in him, or whoever does not wait for his coming, not only does he defy the other prophets, but also the Torah and Moses our teacher."

Maimonides stressed that signs and miracles were not necessarily part of the Messiah's task. Rather, it is by the accomplishment of the messianic mission that he shall be known:

- "Do not imagine that the anointed King must perform miracles and signs and create new things in the world or resurrect the dead and so on. The matter is not so: For Rabbi Akiva was a great scholar of the sages of the Mishnah, and he was the assistant-warrior of the king Bar Kokhba, and claimed that he was the anointed king. He and all the Sages of his generation deemed him the anointed king, until he was killed by sins; only since he was killed, they knew that he was not. The Sages asked him neither a miracle nor a sign... And if a king shall stand up from among the House of David... [and] if he succeeded and built a Holy Temple in its proper place and gathered the strayed ones of Israel together, this is indeed the anointed one for certain..."

Maimonides' pragmatism gave way in the later middle ages to a wave of mystical thought based on the Kabbalah, combined with various medieval superstitions and magical thinking. This together with intense persecution of Jews in Europe provided a fertile ground for active messianic expectations. One particular messianic figure deserves special mention: Shabbetai Zevi, for he won the allegiance of a very large proportion of European and near Eastern Jewry. Even his eventual apostasy to Islam did not put an end to messianic hopes in him, as his followers rationalized it as a sacrificial act of tikkun, or restorational healing. Later Shabbataeans were accused of moral outrages born of this doctrine, under which the worst sins allegedly became acts of purification. This phenomenon produced a reaction in normative Judaism against messianic tendencies that persists to this day.

Modern Jews' attitude toward the Messiah can be divided into roughly four categories:

Orthodox Judaism today maintains that Jews are obligated to accept Maimonides' 13 Principles of Faith, including an unwavering belief in the coming of the Messiah as traditionally defined.

Conservative Judaism takes a more flexible stand. Its statement of principles declares:

- "Since no one can say for certain what will happen in the Messianic era each of us is free to fashion personal speculation. Some of us accept these speculations are literally true, while others understand them as elaborate metaphors... We echo the words of Maimonides based on the prophet Habakkuk (2:3) that though he may tarry, yet do we wait for him each day."

Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism generally do not accept the idea that there will be a personal Messiah. Many, however, believe in the ideal of a messianic age, the realization of which is the obligation of all Jews. In 1976, the Central Conference of American Rabbis, the official body of American Reform rabbis, sated:

- We affirm that with God's help people are not powerless to affect their destiny. We dedicate ourselves, as did the generations of Jews who went before us, to work and wait for that day when "They shall not hurt or destroy in all My holy mountain for the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord as the waters cover the sea."

Many Secular Jews also remain committed to the ideal of the Messiah in their way. Even those who have abandoned formal religion altogether often work for utopian social causes that can be thought of as messianic: socialism, Zionism, the Green movement, New Age groups, etc.

Jewish messiah claimants

This list features people who are said, either by themselves or their followers, to be the Jewish Messiah.

- Cyrus of Persia (sixth century B.C.E.)

- Zerubbabel, governor of Jerusalem (sixth century B.C.E.)

- Judas of Galilee (Ezekias)(c. 4 B.C.E.)

- Simon (c. 4 B.C.E.)

- Athronges (c. 4-2? b.c.e.)

- Jesus of Nazareth (c. 4 B.C.E. - c. 30 C.E.)

- Theudas (44-46]) in the Roman province of Judea

- Menahem ben Judah, partook in a revolt against Agrippa II in Judea

- Simon bar Kokhba (died c. 135), ruled an independent state for three years.

- Moses of Crete (5th century)

- Abu 'Isa al-Isfahani of Ispahan lived in Persia during the reign of the Umayyad Caliph 'Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (684-705).

- Yudghan, lived and taught in Persia in the early eighth century

- Serene (Sherini, Sheria, Serenus, Zonoria, Saüra) (c. 720)

- David Alroy or Alrui (c. 1160)

- Abraham Abulafia (b. 1240)

- Nissim ben Abraham (c. 1295)

- Moses Botarel of Cisneros (c. 1413)

- Asher Lemmlein (1502) a German near Venice.

- David Reuveni and Solomon Molko early sixteenth century.

- Sabbatai Zevi (alternative spellings: Shabbetai, Sabbetai; Tvi, Tzvi) (1626-1676}

- Barukhia Russo (Osman Baba), successor of Sabbatai Zevi.

- Miguel (Abraham) Cardoso (b. 1630)

- Mordecai Mokia ("the Rebuker") of Eisenstadt (active 1678-1683)

- Jacob Querido]), said to be the reincarnation of Shabbetai Zevi.

- Löbele Prossnitz (Joseph ben Jacob), early eighteenth centur.y

- Jacob Joseph Frank (1726-1791), founder of the Frankist movement.

- Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rabbi, (1902-1944).

Islamic Views

In the Holy Qur'an, the scripture of Islam, Isa (Jesus) is recognized as the Messiah as well as a prophet or Messenger of God. However, Muslims staunchly deny that Jesus is the Son of God or that he pre-existed his birth, as the Second Person of the Trinty. On the other hand, they affirm that he was born of the virgin Mary, that he was raised to heaven, and that he will return at the end of days to live out the rest of his natural life. Muslims believe that true prophets are protected by God, who will not allow them to be killed by their enemies or executed. They therefore reject the doctrine that Jesus was crucified and that his death was an atonement for mankind's sins.

The Mahdi is a different person from Jesus/Isa and is separate messianic figure in Islam. The Mahdi will usher in a new age of peace, and restore a perfect Islamic society. Shia and Sunni opinions on al-Mahdi differ somewhat, but both sects agree that Jesus was the Messiah, as they understand the term.

Muslim messiah claimants

Islamic tradition has a prophecy of the Mahdi, who will come alongside the return of Jesus. The following people claimed to be the Mahdi.

- Syed Mohammad Jaunpuri (1443 - 1505) of Northeastern India.

- The Báb in 1844 declared to be the promised Mahdi in Shiraz, Iran.

- Bahá'u'lláh (1817-1892): He was born Shiite and relates to both Islam as well as Christianity. He claimed to be the promised one of all religions, and founded the Bahá'í Faith.

- Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835 - 1908) of Qadian, India, considered to be 'the Promised Messiah' return of Jesus, founder of the Ahmadiyya religious movement in Islam.

- [Muhammad Ahmad in the late 19th century founded a short-lived empire in Sudan.

- Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan of Somaliland engaged in military conflicts from 1900 to 1920.

- Juhayman al-Otaibi seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca in November of 1979.

- Ayatollah Seyyed Ruhollah Khomeini of Iran (1900-1989) was believed by a number of followers to be the Mahdi.

Other Messiahs

There have been many other messiah claimants over the millennia. In the religions of Asia, the idea of Messiah has also been present. For example, the bodhisattva Maitreya plays a similar function as a Messiah in Buddhism. Maitreya is said to be the future Buddha in Buddhist eschatology whom some Buddhists believe will eventually appear on earth, achieve complete enlightenment, and teach the pure dharma. He is predicted to be a “world-ruler.” The prophecy of the arrival of Maitreya is found in the canonical literature of all Buddhist sects (Theravāda, Mahāyāna, Tantrayana, Navayana, Purnayana, Triyana and Vajrayāna) and is accepted by most Buddhists as a statement about an actual event that will take place in the distant future.

It is said that Maitreya’s coming will occur after the teachings of the current Buddha Gautama, the Dharma, are no longer taught and are completely forgotten. In order for the world to realize the coming of Maitreya, a number of conditions must be fulfilled. Gifts should be given to Buddhist monks, moral precepts must be followed, and offerings must be made at shrines. Some of the events foretold at the coming of the second Buddha include an end to death, warfare, famine, and disease, as well as the ushering in of a new society of tolerance and love.

While a number of persons have proclaimed themselves to be Maitreya over the years, none have been officially recognized by the Buddhist sanghas (communities). A particular difficulty faced by any would-be claimant to Maitreya's title is the fact that the Buddha is considered to have made a number of fairly specific predictions regarding the circumstances that would occur prior to Maitreya's coming- such as that the teachings of the Buddha would be completely forgotten, and all of the remaining relics of Sakyamuni Buddha would be gathered in Bodh Gaya and cremated.

The Bahá'ís believe that Bahá'u'lláh is the fullfillment of the prophecy of appearance of Maitreya.[1] Bahá'ís believe that the prophecy that Maitreya will usher in a new society of tolerance and love has been fulfilled by Bahá'u'lláh's teachings on world peace.[1]

Very often Christian or Muslim missionaries in predominantly Buddhist countries link the prophecy of Maitreya to their saviors, such as Christ or Muhammad.

The Unificationist View

Scholarly reflections on Unificationism would tend to see in it a type of middle ground between the Jewish and Christian concepts of the Messiah. It shares with Judaism a belief that the Messiah is not God (or a god) but a normal human being with a divine mission. It also affirms, as Judaism does, that Jesus of Nazareth was obstructed from completing fully his Messianic Task. However, with Christianity, Unificationism affirms that Jesus was indeed chosen by God to be the Messiah and that his death on the Cross was used by God as a condition for mankind's atonement. Therefore by believing in Jesus, people can gain spiritual salvation or rebirth. Unificationists also affirm a belief in the Trinity, but not in the traditional sense. Rather, they see Jesus and the Holy Spirit as a second Adam and Eve, who give rebirth to Christians.

Unificationists teach that the mission of the Messiah is carried out, not by one man but a couple, a restored Adam and Eve who become True Parents and create a lineage of goodness. True Parents pioneer the original purpose of creation, and from this position engraft all humankind to embark on our responsbility to meet our own destiny to become true sons and daughters of God and grow to become a true parents ourselves. They believe that the founders of the Unification movement, the Reverend and Mrs. Sun Myung Moon, have inherited the mission of Messiah from Jesus and the Holy Spirit to continue with the original mission to found the Kingdom of God on Earth and in Heaven. In so doing, Rev. and Mrs. Moon simultaneously fulfill the missions of all the messiah-figures of all the world's religions. The formal title given to the messianic couple in Unificationism is the "True Parents."

Notes

- 1. Momen, Moojan (2002-03-02). Buddhism and the Baha'i Faith. bahai-library.org. Retrieved on 2006-06-28.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ali, Shaukat: Millenarian and Messianic Tendencies In Islamic Thought: Lahore: Publishers United: 1993

- Ankerberg, John; Weldon, John: “Chap. 11. Biblical Prophecy—Part One”, Ready With an Answer for the Tough Questions About God. Eugene, OR: Harvest House Publishers. ISBN 1-56507-618-4.

- Hogue, John Messiahs: The Visions and Prophecies for the Second Coming (1999) Elements Books ISBN 1862045496

- Furnish, Timothy: Holiest Wars: Islamic Mahdis, Jihads and Osama Bin Laden: Westport: Praeger: 2005: ISBN: 02759833838

- Maimonides, Moses: Mishneh Torah, Chapter on Hilkhot Melakhim Umilchamoteihem (Laws of Kings and Wars)

- Sachedina, Abdulaziz Abdulhassan: Islamic Messianism: The Idea of the Mahdi in Twelver Shi'ism: Albany: State University of New York Press: 1981: ISBN: 0873954580

- Emet Ve-Emunah: Statement of Principles of Conservative Judaism, Ed. Robert Gordis, Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1988

- Reform Judaism: A Centenary Perspective, Central Conference of American Rabbis

External links

- The Maitreya Project is building a 500ft/152m bronze statue of Maitreya Buddha near Kushinagar (previously planned in Bodhgaya).

- The Coming Buddha (Ariya Metteyya), Research Papers by Sayagyi U Chit Tin

- The Bodhisattva Ideal - Buddhism and the Aesthetics of Selflessness.

- A Contemplation on Maitreya - The Coming Buddha

External links

- Principles of Moshiach and the Messianic Era in Jewish Law

- Moshiach: an Anthology

- Moshiach Ben Yosef

- Moshiach: A Torah Perspective (Chabad Meshichist)

- Who is the Messiah? by Jeffrey A. Spitzer

- Expectations in 1st Century Judaism—Documentation From Non-Christian Sources

- Characteristics of Islam’s Messianic Figure: The Mahdi

- Mashiach Rabbi Jacob Immanuel Schochet, published by S.I.E., Brooklyn, NY, 1992

- The Messianic Hope

- Shabbetai Zevi

- Rev. Sun Myung Moon

Non-specific religious

- Introduction to Messianism Large website

- Messiah in the 1911 Encyclopedia Brittanica

- Rabbi Chaim Vital Calabrese

- Moshiach According to Torah Sources

- Moshiach Online

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Messiah

Christian

- Christian view of the Messiah

- Fulfilled Bible prophecies: Messianic

- Jesus and the Messianic cycle

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Messiah

Moslem

- The Concept of Messiah in Islam

- The Canadian Society of Muslims On-line library project and resource center.

- Islamic Perspectives

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

See also

- Anointing of Jesus

- Chosen one, a person who was chosen, usually by fate or God (or a godlike being), to save a group of people.

- God complex

- Jewish Messiah

- Kalki

- Mahdi

- Maitreya

- Messianic prophecy

- Millennialism

- Muhammad al-Mahdi

- Messiahs in fiction and fantasy

- Sun Myung Moon

- Saoshyant

- Second Coming

- Shambhala

- List of people considered to be avatars

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Momen, Moojan (2002-03-02). Buddhism and the Baha'i Faith. bahai-library.org. Retrieved 2006-06-28.