Difference between revisions of "Ghetto" - New World Encyclopedia

| (144 intermediate revisions by 13 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Status}} | ||

[[Category: Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category: Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category: Sociology]] | [[Category: Sociology]] | ||

| + | [[Category: Submitted]] | ||

| + | [[File:Ghetto (Venice) Panorama.jpg|thumb|400px|The main square of the Venetian Ghetto, Italy]] | ||

| + | A '''ghetto''' is an area where people from a specific ethnic background, [[culture]], or [[religion]] live in seclusion, voluntarily or more commonly involuntarily with varying degrees of enforcement by the dominant social group. The first ghettos were established to confine [[Jewish]] populations in [[Europe]]. They were surrounded by walls, segregating and so-called "protecting them" from the rest of society. In the [[Nazi]] era these ghettos served to confine and subsequently exterminate Jews in massive numbers. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Today the term '''ghetto''' is used to describe a blighted area of a city containing a concentrated and segregated population of a despised minority group. These concentrations of population may be planned, as through government-sponsored housing projects, or the unplanned result of self-segregation and migration. Often municipalities will build highways and set up industrial districts around the ghetto to further isolate it from the rest of the city. The continued existence of ghettos in many parts of the world is a blight upon humanity that requires resolution. | ||

| − | + | ==Origin and definition of term== | |

| − | + | {{readout|Historically, the term "ghetto" referred to restricted housing zones where [[Jew]]s were required to live|right}}. The original ghetto was formed by the Jewish immigrants to [[Ghetto#Venetian_Ghetto|Venice]] in the fourteenth century, who settled in the place where a former iron foundry ''(getto)'' used to be. Other suggested etymologies include ''Ghetonia,'' the [[Greek]] word for "neighborhood," ''borghetto,'' [[Italian]] for "small neighborhood," or the [[Hebrew]] word ''get,'' literally meaning a "bill of divorce." | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Ghettos are characterized by four specific conditions present in varying degrees of severity: "social ostracism," "economic hardship," "legal arbitrariness from the side of authorities," and "security," which term has taken on different meanings in different historical eras and geographical locations. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The term "ghetto" has come to label any poverty-stricken or [[sociology|sociologically]] defined urban minority area whose population lives differently from the rest of the larger society due to the conditions that characterize ghettos. In the [[United States]], the word "ghetto" has also come to be used as an adjective to describe a certain way of dressing, speaking, and behaving. In this sense, "Ghetto" constitutes a subculture, especially among teenagers in urban centers, associated with hip-hop music and a rebellious attitude. As it has become a slang term of art among young people, the meaning of the term morphs constantly. | |

| − | + | ==Jewish Ghettos in Europe== | |

| − | + | ===Thirteenth–Nineteenth Centuries=== | |

| − | The character of ghettos | + | The first ghettos appeared in [[Italy]], [[Germany]], [[Spain]], and [[Portugal]] in the thirteenth century following the recommendation of [[Pope Pius V]] that all the bordering states should set up ghettos. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, all the main towns (with exception of Livorno and Pisa) had complied. In medieval Central [[Europe]], ghettos existed in [[Paris]], [[Frankfurt]], [[Mainz]], [[Prague]], and even further East, in [[Poland]] and [[Russia]]. The treatment of [[Judaism|Jews]] in those more easterly regions was more arbitrary and harsher, as the authorities often left the ghettos open and therefore vulnerable to attack by those, sometimes even more impoverished, who lived outside the ghettos. |

| + | |||

| + | The character of ghettos also varied. There were times in which a ghetto featured relative affluence (e.g. in sixteenth century [[Venice]] and in Prague in the fifteenth century). At other times, even a relatively affluent ghetto became impoverished, having lost [[politics|political]] concessions or (as in Prague) [[trade|trading]] privileges. Their character also depended on the circumstances in which the ghettos were established. While some ghettos (e.g. Venice) were established after negotiations between the city and the Jews, others (e.g. Frankfurt) obliged the Jews to move there by a city ordinance. | ||

| − | Since Jews could not acquire land outside the ghetto, | + | Since Jews could not acquire land outside the ghetto, the landscape was transformed into narrow streets and tall, crowded houses. Walls and gates stood around the ghetto and were closed and locked from the inside (during [[Easter]] week) and from the outside (during [[Christmas]]) to prevent [[anti-Semitic]] violence or [[pogrom]]s. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Social ostracism often resulted in residents being required to obtain passes to go outside the ghetto boundaries. They were socially isolated, although not necessarily [[culture|culturally]] and [[cognition|intellectually]], since they had their own [[school]] system based on [[synagogue]]s, and they set up their own communal authority to improve security. Thus, in some ways, the segregation sometimes benefited both sides. | ||

| + | Jewish ghettos were progressively abolished in the 19th century following the ideals of the [[French Revolution]]. This started in Western European countries when the establishment of tolerant governments, such as [[Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleon]]'s [[France]] and the [[United Kingdom]], encouraged industrious Jews to immigrate. In 1870, after the Papal States were overthrown, the last ghetto in Western Europe was abolished; the walls physically torn down in 1888. In [[Russia]], however, the Jewish Pale continued to exist until the [[Russian Revolution of 1917]]. | ||

| + | |||

====Venetian Ghetto==== | ====Venetian Ghetto==== | ||

| − | The '''Venetian Ghetto''' was the area | + | The '''Venetian Ghetto''' was the area in Venice in which [[Judaism|Jewish]] people were required to live under the [[government]] of the Venetian Republic. |

| − | + | Restrictions on their movement and permitted trades varied, but money-lending, running pawnshops, dealing in second hand goods, and tailoring were common occupations. In 1516, they were moved to the area known as the ''Ghetto Nuovo,'' Surrounded by [[canal]]s, this area was linked to the rest of the city by only two bridges, which were closed at night and during certain [[Christianity|Christian]] festivals, when all Jews were required to stay in the Ghetto. | |

| − | + | In 1541, the quarter was enlarged to cover the neighboring ''Ghetto Vecchio,'' and in 1633, the ''Ghetto Nuovissimo'' was also added. Due to population density, buildings rose to six or more stories. | |

| − | + | The area is still home to five synagogues connected by a secret corridor. They are known for their interiors, the oldest ''(Schola Grande Tedesca)'' dating from 1528. The ''Scola Spagnola'' now houses the Museum of Hebrew Art. | |

| − | + | ====Roman Ghetto==== | |

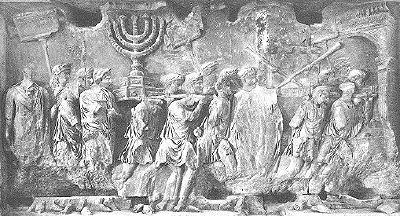

| + | [[Image:Sack of jerusalem.JPG|thumb|400px|Detail from the Arch of Titus showing spoils from the Sack of Jerusalem]] | ||

| + | The '''Roman Ghetto''' was located in the area close to the river [[Tiber]] and the Theater of Marcellus in [[Rome]], [[Italy]]. | ||

| − | + | Papal decree ''Cum nimis absurdum,'' promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1555, segregated the [[Judaism|Jews]] in a walled quarter with gates that were locked at night, and subjected them to various restrictions (e.g. limits on permitted professions) and degradations (e.g. compulsory [[Catholic]] sermons on the Jewish ''[[shabbat]]''), although to a lesser degree than in other European countries. The district lacked a well and flooded every winter. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | When [[Napoleon Bonaparte|Napoleonic]] forces occupied Rome, the Ghetto was legally abolished, in 1808, but it was reinstated as soon as the Papacy regained control. In 1848, during the brief revolution, the ghetto was abolished once more, again temporarily. The Jews had to petition annually for permission to live there, and were restricted from owning any [[property]], even within the ghetto. They paid an annual [[taxation|tax]] for the privilege of living there and annually had to swear loyalty to the [[Pope]] by the Arch of Titus, which celebrates the [[Roman]] sack of [[Jerusalem]]. | |

| − | + | Pope Leo XIII was less intransigent than Pius IX. The city of Rome was able to tear down the ghetto's walls in 1888 and demolish some houses before the area was reconstructed around the new [[synagogue]]. | |

| − | + | ===World War II=== | |

| + | [[Image:Getto pomnik.jpeg|thumb|right|400px|The Ghetto Heroes' Memorial]] | ||

| + | The [[Nazi]]s re-instituted [[Judaism|Jewish]] ghettos in Eastern Europe before and during [[World War II]]. However, the nature of these ghettos was dramatically different. Explicit [[anti-Semitism]] in Nazi ideology developed into an official state policy requiring Jews to be confined in the ghettos and later shipped to [[concentration camp]]s. The same policy was instituted in all countries under the [[Third Reich]]'s control, with most of the Jews confined into tightly packed areas in the cities of Eastern Europe. Some of the more notorious ghettos were in [[Ghetto#Warsaw Ghetto|Warsaw]], Lublin, [[Ghetto#Lodz Ghetto|Lodz]], Tuliszhkow, Radom, Opole, Kielce, Bialystok, and [[Ghetto:Krakow|Krakow]] in [[Poland]], Riga, Vilno, Vitebsk, Pinsk, Lvov, and Smolensk in [[Russia]], and Budapest in [[Hungary]]. All social, [[economics|economic]], and [[law|legal]] privileges ceased to exist there and were supplanted by state control. | ||

| − | Nazi | + | Starting in 1939, the Nazi regime began moving Polish Jews into designated ghettos in Tuliszkow (in December, 1939), in Lodz (in April, 1940), in Warsaw (in October, 1940), and into many other ghettos throughout 1940 and 1941. The ghettos were walled off, just like in [[medieval]] times, except that any Jew found leaving was shot. |

| − | + | The situation in the ghettos was brutal. As the Jews were not allowed out of the ghetto, they had to rely on food supplied by the Nazis. With crowded living conditions, starvation diets, and little sanitation (in the Lodz Ghetto a full 95 percent of the apartments had no sanitation or running water), hundreds of thousands of Jews died of [[disease]] and starvation. In 1942, the Nazi government began "Operation Reinhard," which was the systematic deportation of Jews to extermination camps. During the [[Holocaust]], the authorities deported Jews from everywhere in Europe to these ghettos, or directly to the camps. In some ghettos local resistance organizations started uprisings. However, none were successful, and the Jewish population of the ghettos was almost entirely annihilated. | |

| + | ====Warsaw Ghetto==== | ||

| − | The '''Warsaw Ghetto''' was the largest of the [[ | + | The '''Warsaw Ghetto''' was the largest of the [[Judaism|Jewish]] ghettos in [[World War II]]. In the three years of its existence, starvation, disease, and deportations to concentration camps dropped the population of this ghetto from an estimated 450,000 to 37,000. |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The Warsaw Ghetto was opened on October 16, 1940 to receive about 380,000 people, approximately 30 percent of the population of Warsaw despite being only 2.4 percent of its area. The [[Nazi]]s then built a wall, effectively closing off the Warsaw ghetto from the outside world on November 16, 1940. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In early 1942, the Nazis began to exterminate the Jews of Europe. The first phase was to eliminate the Jews in [[Poland]]. After the construction of extermination camps was completed in July 1942, the wholesale liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto was set to begin. | |

| − | + | On January 18, 1943, armed resistance started. There was some initial success, which was followed by three months of fighting. The final battle started on the eve of [[Passover]], April 19, 1943. During the fighting approximately 7,000 Jewish partisans were killed and 6,000 were burned alive or gassed in bunkers. The remaining 50,000 people were sent to German concentration camps. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Lodz Ghetto==== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Ghetto bridge.JPG|right|thumb|400 px|Jews using a wooden bridge to cross from one section of the Lódz Ghetto to the other. Entering the non-ghetto thoroughfare was forbidden to Jews.]] | |

| + | [[Image:Children headed for deportation.JPG|right|350px|thumbnail|Children being marched to the trains that will take them to their death]] | ||

| + | The '''Lodz Ghetto''' was the second-largest ghetto (after the Warsaw Ghetto) established for Jews in [[Nazi]]-occupied [[Poland]]. Situated in the town of Lódz, with 672,000 inhabitants and originally intended as a temporary gathering point for Jews, the ghetto was transformed into a major industrial center, providing much needed supplies for Nazi Germany and especially for the [[Wehrmacht|German Army]]. It transformed the Jewish population (reduced from 233,000 to about 164,000) into a [[slave labor]] force. Over the years, Jews from Central Europe and as far away as [[Luxembourg]] were deported to the ghetto. A small [[Rom]]a population was also resettled there. | ||

| − | + | Even though the work was essential to the ghetto's survival, and despite the [[Third Reich]]'s Armaments Minister Albert Speer advocating the ghetto's continued existence as a source of cheap labor, in the summer of 1944 the final order came to start gradual liquidation of the remaining population. By late August of that year, the last ghetto in Europe was eliminated. | |

| − | + | The peculiar situation of the Lódz Ghetto, namely conviction that productivity would ensure survival, coupled with brutal Nazi administration, prevented any manifestations of armed resistance such as in the Warsaw ghetto uprising. However, defensive resistance in the ghetto saved many Jews from final transportation. | |

| − | + | ====Krakow Ghetto==== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Krakow Ghetto 06694.jpg|thumb|400px|right|Deportation of Jews from the Kraków Ghetto, March 1943]] | |

| − | + | The [[Jew]]ish ghetto in [[Kraków]] (Cracow) was one of the five main ghettos created by the [[Nazi]]s during their occupation of [[Poland]] during [[World War II]]. Before the war, Kraków was an influential cultural center for the 60,000-80,000 Jews that resided there. However, in May 1940, the Nazis announced that Kraków should become the "cleanest" city in the General Government and ordered a massive deportation of Jews from the city. Of the more than 68,000 Jews in Kraków, only 15,000 workers and their families, all crammed into 30 streets, 320 residential buildings, and 3,167 rooms, were permitted to remain due to the policy of separating "able workers" from those who would later be exterminated. | |

| − | + | The armed underground resistance in the ghetto had some success, but, unlike in Warsaw, their efforts did not lead to a general uprising before the ghetto was liquidated. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | From May 30, 1942 onward, the Nazis implemented systematic deportations from the ghetto to surrounding [[concentration camp]]s. Thousands of Jews were transported over the succeeding months. The final 'liquidation' of the ghetto came in March 13 - March 14, 1943 when 8,000 Jews, deemed able to work, were transported to the Kraków-Płaszów labor camp. Any remaining were killed or sent to die in [[Auschwitz]]. | |

| − | + | ==Post-War Ghettos in the World== | |

| − | + | ===South African and African ghettos=== | |

| − | + | [[Image:Joburg.iss.400pix.jpg|thumb|400px|Johannesburg, including Soweto, from the [[International Space Station]]]] | |

| + | In [[South Africa]] under the apartheid policies, The Group Areas Act of April 27, 1950 barred people of particular races from residing in various urban areas. One of the most notorious “black ghettos” was Soweto, a mostly black urban area to the south west of [[Johannesburg]]. During [[apartheid]] regime, Soweto was constructed for the specific purpose of housing African people who were then living in areas designated by the government for white settlement, such as the multi-racial area called Sophiatown. Today, Soweto is among the poorest parts of Johannesburg. However, there have been signs of economic improvement, and Soweto has become a center of nightlife. | ||

| − | [[ | + | There are other "ghettos" in South Africa, such as KwaMashu in Durban in the KZN province. Resettlements, comparable to forced deportations in [[Poland]], into specific, ghetto-like areas were quite common elsewhere in [[Africa]], especially along the [[Zambezi River]]. Before the [[Kariba Dam]] was constructed in 1956, whole tribes were forcibly moved into economically inhospitable inland areas. |

| − | + | ===Ghettos in the United States=== | |

| − | + | In the [[United States]], during the period between the abolition of [[slavery]] and the passing of the civil rights laws in the 1960s, discriminatory notions, sometimes codified in law, forced many urban African Americans to live in specific neighborhoods, such as Bronzeville in Chicago and Harlem in [[New York City]], which became known as "ghettos." The [[Civil Rights Act]] allowed wealthier African Americans to move to formerly all-white areas. The result of this was that the economic bases of many ghettos collapsed, leaving them as zones of below-average income, poorly-maintained housing, and high [[crime]]. For example, by the 1970s, the Robert Taylor Homes, located in Chicago's Bronzeville, was home to the poorest and third-poorest [[census]] tracts in the United States. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The formation of the ghettos and the black underclass forms one of most controversial issues in [[sociology]]. One of the earliest studies of the modern phenomenon of ghetto formation was Daniel Patrick Moynihan's 1965 work ''The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,'' often referred to as the "Moynihan Report." This report noted that the number of black welfare cases was rising, while employment was falling. It also pointed out that a quarter of all black children were born to unmarried women, and that this percentage was rising. The ghetto was described as a "tangle of pathologies," and Moynihan predicted that conditions would only worsen. | |

| − | + | In the 1980s, a revival of all "ghetto-encompassing" questions occurred, as well as the development of new theories on why these ghettos emerged. Charles Murray argued in ''Losing Ground'' that "Great Society" [[liberalism]] created the hopeless poor. Murray claimed that the eligibility of single women for welfare encouraged women to have babies out of wedlock, and that welfare discouraged all from working. Murray concluded his book with a call for the abolition of welfare. On the other hand, William Julius Wilson argued in ''The Truly Disadvantaged'' that easy access to welfare had little effect on women's decisions on childbearing. Wilson claimed, instead, that the flight of low-skilled manufacturing jobs to the suburbs and the Southern states left blacks economically isolated in the ghettos due to their "spatial mismatch." Wilson thus explained the high percentage of out-of-wedlock births by the lack of "marriageable" (i.e. employed and single) men. | |

| − | [[ | + | Yet another theory of ghetto formation was offered by Roger Waldinger in ''Still the Promised City?'', which detailed a mismatch between the wages that blacks desire and the wages which low-skilled jobs actually pay. In looking at New York City, Waldinger pointed out that new immigrants living in similar “ghettos” ([[Korea]]ns, [[China|Chinese]], [[Pakistan]]is, [[Dominican Republic|Dominicans]], etc.) often fared better than American-born blacks. Waldinger also noticed that southern-born and [[Caribbean]]-born blacks had higher incomes than northern-born blacks. Waldinger argued that immigrant groups benefited by establishing nepotistic niches for themselves, and used niches for mutual help, something blacks in most cases were unable to do. Waldinger also noted that even though hotels and restaurants may offer very low wages, they still outclass wages in [[Mexico]], rural China, or [[Africa]]. Thus, immigrants readily accept them. By contrast, unskilled northern-born blacks, who hope to do something better than their parents, disdain these jobs and may often wind up working outside the legitimate economy. |

| − | + | Thus, despite various attempts to improve social and economic conditions, although the legal arbitrariness practically disappeared in post-1964 American ghettos, the ghetto attributes of social ostracism and economic hardship are still generally held. In terms of the security aspect, apart from addressing the alarmingly high [[crime]] rate, there has not been any state intrusion into life in these ghettos whatsoever, meaning that residents are not legally or physically restricted from leaving. This constitutes the specifically "American way" of ghetto life, which differs from that found in other parts of the world. | |

| − | + | While the American “melting pot” lessened the importance of ethnic origin, [[culture]], and [[religion]]—although some of it returned as “ethnic profiling” after [[9/11]]—quite different situations developed in [[Europe]]. | |

| − | + | ===European Ghettos=== | |

| − | + | Based on the four definitional attributes, ghettos exist in most, if not all, of the [[industry|industrialized]] [[Europe]]an countries even in the twenty-first century. There are, of course, no more Jewish ghettos. Contemporary European problems involve visible minorities, namely recent, and second, if not third, generation immigrants. | |

| − | + | In [[France]], the poorer ''banlieues,'' or suburbs, especially those of [[Paris]], house an impoverished population, largely of [[North Africa]]n [[Muslim]] and black [[Africa]]n origin, in large high-rise building developments known as ''Cités.'' These were built in the 1960s and 1970s in the industrial suburbs to the north and east of Paris, especially in the Seine-St-Denis area, as well as in other French cities like Villeurbanne near Lyon. They are similar in style to the large, inner-city, urban renewal projects in the [[United States]], such as the former Cabrini Green in Chicago, and have similar problems. Though most of the young people were born in France, and are citizens, this North-African and African population has suffered routine discrimination in the job market as well as by the [[police]]. The 2005 riots in France originated within these ghettos as a reaction to legal discrimination and the attitude of French society that the minorities in ghettos threaten their secularism. Thus, although the generally poor economic situation aggravated social hardship, it was mostly the legal and security attributes that incited the unrest. On the other hand, most of the recent African immigrants, from places such as [[Cote d'Ivoire]] and [[Dakar, Senegal]], prefer the biased, but functioning, legal system in the French ghettos over the complete breakdown and chaos in their home countries. | |

| − | + | In [[Germany]], the “post-war economic miracle” happened with considerable help from [[Turkey|Turkish]] immigrants. They came, officially invited in, to boost a much-needed [[labor]] force in the heavy machinery sectors and, as in France, they settled in ghettos. They did not seem to mind, and certainly their social, economic and overall way of life dramatically improved, as long as the “economic miracle” lasted. With increasing unemployment in the machinery sector and other [[industry|industries]], the state had to step in and, to preempt [[riot]]s, offered the Turkish families reasonable settlements if they returned to their homeland. | |

| − | + | ===Roma Problem: Czech Republic and Slovakia=== | |

| + | [[Rom]]a, or Gypsies—with their basically [[nomad]]ic way of life, their reluctance to stay and try to become assimilated into any one country, their absence of a common [[language]], and their lack of marketable skills—have caused problems for Eastern and Central European governments for centuries. Their nomadic way of life saved them from being put into ghettos (or worse still, [[concentration camp]]s) until after the [[World War II|Second World War]]. Then, the Eastern European states were forced to act. They categorized the Roma as a "social group" or "problem" and thus legitimized intrusive state intervention to deal with them. | ||

| − | + | Another aspect of this redefinition of Roma [[identity]] was the transformation of their ethnic and [[culture|cultural]] difference into social deviance. Roma children who did not speak the host language very well were treated as mentally deficient and put into special classes within which they could advance only to the fourth grade. Young Roma thus became increasingly alienated and isolated from the host society, experiencing an enforced "social retardation," which led to withdrawal, [[aggression]], and other forms of antisocial behavior. Perhaps the most radical instance of such intervention was the policy of [[sterilization]] adopted by the [[Slovak]] government between 1980 and 1990 to curb what it called "unhealthy high fertility rates" among the Roma. | |

| − | '' | + | After the [[Communism|Communist]] regimes ended in Eastern Europe, prejudice towards the Roma increased. For example, a 1991 ''Times Mirror'' survey found that Europeans in overwhelming numbers expressed contempt for Roma: 59 percent of [[German]]s, 91 percent of [[Czechoslovakia|Czechoslovaks]], 71 percent of [[Bulgaria]]ns, 79 percent of [[Hungary|Hungarians]], and 50 percent of [[Spain|Spaniards]]. Other polls showed similar negative views of Roma. |

| − | + | By the end of the twentieth century, Roma ghettos had appeared in the [[Czech Republic]]. The Roma moved there, both voluntarily and involuntarily, when municipalities forcibly relocated them from other areas. The majority of those living there are unemployed and uneducated, and the [[crime]] rate is high. As the ghetto develops, non-Roma people move away. The most infamous ghetto in the Czech Republic is Chánov, in the city of Most. | |

| − | + | In the case of the Roma, all four ghetto attributes are in evidence: they have a tentative legal status, social and economic hardships are on the rise, and they are relocated into ghettos by the state, allegedly to protect them from the prejudice and harassment of the society, but in reality to deal with a problem to which they have no other solution. | |

| − | + | ==Cultural Life and the Ghetto== | |

| − | + | It is often said that great [[art]] is born out of suffering, and so it is not necessarily a coincidence that great artists lived, and still live, in ghettos. Ghettos often became known as vibrant cultural centers, for example Harlem in New York in the 1920s and 1930s. Artists such as [[Bob Marley]], [[Ice Cube]], [[John Lee Hooker]], [[Cab Calloway]], and [[Tupac Shakur]] were born and raised in ghettos, and much of their music comes from their own suffering, experiences, and life in the ghetto. | |

| − | :'' | + | Even in [[Nazi]]-run ghettos during the [[World War II|Second World War]] cultural events did take place: lectures, concerts, theater, and art exhibits. In many cases, the artists and performers were prominent figures in Polish cultural life. Movie director [[Roman Polanski]], a survivor of the ghetto, recalled his experience in his memoirs, ''Roman.'' In the [[Theresienstadt]] ghetto, in the fortress of [[Terezín]] in former [[Czechoslovakia]], the inhabitants formed [[orchestra]]s as well as chamber groups and [[jazz]] ensembles. Several stage performances were produced and attended by camp inmates, although they were often coerced into performing by the Nazis for [[propaganda]] purposes. Many of the composers and other artists were subsequently sent to [[Auschwitz]] where they died in the [[gas chamber]]s. [[Karel Ancerl]] escaped this fate, although his family did not, becoming a world-renowned conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and later the Toronto Symphony Orchestra. |

| − | [[ | + | It is acknowledged that the "renaissance," and even the "golden era," of Czech and Slovak [[literature]] of the post-war period occurred during the 1970s and 1980s in [[Czechoslovakia]] under the [[Communism|Communist]] regime. There, several hundred intellectuals (writers, scientists and artists), who signed the anti-communist proclamation “Chartist Movement,” suffered at the hands of the Czech State Security Police. They lost their jobs, were forbidden to publish or exhibit their work, were shadowed by agents constantly, and, hence, ostracized by the general public because of the police presence. All the definitional properties of the classic ghetto were in force, and they even used the term themselves to describe their situation. And yet, the best works by writer [[Ludvik Vaculik]], by playwrights [[Pavel Kohout]] and former Czech president, [[Vaclav Havel]], by scientist [[Vaclav Cerny]], and many others, were done during this “ghetto period.” |

| − | + | ==Conclusion== | |

| − | + | The occasional eruption of [[art]]istic flourishing notwithstanding, the most significant feature of ghettos is the cold and inhuman logic that led to their creation. In each case, the purpose was to move a minority, deemed troublesome to the authorities, within protective walls, real or virtual, without any legal recourse. Those authorities used all means—killing included—to prevent residents inside the ghetto from emerging back into the general society. The magnitude of [[moral]] reprehensibility for such intolerant policies, that led to inhumane and eventually [[murder]]ous acts, was not evident to the those responsible for the creation and enforcement of ghettos. The realization of a peaceful world of prosperity for all can only happen when the establishment, and continued presence, of ghettos are no longer deemed justifiable. | |

| − | + | ==References== | |

| − | + | *Murray, Charles. 1984. ''Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980.'' New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465042317 | |

| − | + | *Polanski, Roman. 1984. ''Roman.'' New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0688026214 | |

| − | + | *Silverman, Carol. 1995. [https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/persecution-and-politicization-roma-gypsies-eastern-europe "Persecution and Politicization: Roma (Gypsies) of Eastern Europe."] ''Nationalism in Eastern Europe'' 19.2. Retrieved April1 14, 2023. | |

| − | + | *Waldinger, Roger. 1996. ''Still the Promised City? : African-Americans and New Immigrants in Postindustrial New York.'' Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674838610 | |

| − | + | *Wilson, William Julius. 1990. ''The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy.'' Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226901319 | |

| − | '' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | : | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved April 14, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | * [http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/krakow%20ghetto.html Kraków Ghetto history] ''Death Camps'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-l-oacute-dz-ghetto Ghettos: The Lódz Ghetto] ''Jewish virtual library'' | ||

| + | * [http://www.deathcamps.org/occupation/warsaw%20ghetto%20liquidation.html Warsaw Ghetto Liquidation] ''Death Camps'' | ||

| + | * [https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-warsaw-ghetto Holocaust Ghettos: The Warsaw Ghetto] ''Jewish virtual library'' | ||

| + | * [http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/places/theresienstadt/ Theresienstadt] ''Music and the Holocaust'' | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credits|Ghetto|37543289|Roman_Ghetto|34553665|Venetian_Ghetto|36203521|Warsaw_Ghetto|37575495|Lodz_Ghetto|30603809|Krakow_Ghetto|37277064|}} |

Latest revision as of 23:27, 21 October 2023

A ghetto is an area where people from a specific ethnic background, culture, or religion live in seclusion, voluntarily or more commonly involuntarily with varying degrees of enforcement by the dominant social group. The first ghettos were established to confine Jewish populations in Europe. They were surrounded by walls, segregating and so-called "protecting them" from the rest of society. In the Nazi era these ghettos served to confine and subsequently exterminate Jews in massive numbers.

Today the term ghetto is used to describe a blighted area of a city containing a concentrated and segregated population of a despised minority group. These concentrations of population may be planned, as through government-sponsored housing projects, or the unplanned result of self-segregation and migration. Often municipalities will build highways and set up industrial districts around the ghetto to further isolate it from the rest of the city. The continued existence of ghettos in many parts of the world is a blight upon humanity that requires resolution.

Origin and definition of term

Historically, the term "ghetto" referred to restricted housing zones where Jews were required to live. The original ghetto was formed by the Jewish immigrants to Venice in the fourteenth century, who settled in the place where a former iron foundry (getto) used to be. Other suggested etymologies include Ghetonia, the Greek word for "neighborhood," borghetto, Italian for "small neighborhood," or the Hebrew word get, literally meaning a "bill of divorce."

Ghettos are characterized by four specific conditions present in varying degrees of severity: "social ostracism," "economic hardship," "legal arbitrariness from the side of authorities," and "security," which term has taken on different meanings in different historical eras and geographical locations.

The term "ghetto" has come to label any poverty-stricken or sociologically defined urban minority area whose population lives differently from the rest of the larger society due to the conditions that characterize ghettos. In the United States, the word "ghetto" has also come to be used as an adjective to describe a certain way of dressing, speaking, and behaving. In this sense, "Ghetto" constitutes a subculture, especially among teenagers in urban centers, associated with hip-hop music and a rebellious attitude. As it has become a slang term of art among young people, the meaning of the term morphs constantly.

Jewish Ghettos in Europe

Thirteenth–Nineteenth Centuries

The first ghettos appeared in Italy, Germany, Spain, and Portugal in the thirteenth century following the recommendation of Pope Pius V that all the bordering states should set up ghettos. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, all the main towns (with exception of Livorno and Pisa) had complied. In medieval Central Europe, ghettos existed in Paris, Frankfurt, Mainz, Prague, and even further East, in Poland and Russia. The treatment of Jews in those more easterly regions was more arbitrary and harsher, as the authorities often left the ghettos open and therefore vulnerable to attack by those, sometimes even more impoverished, who lived outside the ghettos.

The character of ghettos also varied. There were times in which a ghetto featured relative affluence (e.g. in sixteenth century Venice and in Prague in the fifteenth century). At other times, even a relatively affluent ghetto became impoverished, having lost political concessions or (as in Prague) trading privileges. Their character also depended on the circumstances in which the ghettos were established. While some ghettos (e.g. Venice) were established after negotiations between the city and the Jews, others (e.g. Frankfurt) obliged the Jews to move there by a city ordinance.

Since Jews could not acquire land outside the ghetto, the landscape was transformed into narrow streets and tall, crowded houses. Walls and gates stood around the ghetto and were closed and locked from the inside (during Easter week) and from the outside (during Christmas) to prevent anti-Semitic violence or pogroms.

Social ostracism often resulted in residents being required to obtain passes to go outside the ghetto boundaries. They were socially isolated, although not necessarily culturally and intellectually, since they had their own school system based on synagogues, and they set up their own communal authority to improve security. Thus, in some ways, the segregation sometimes benefited both sides.

Jewish ghettos were progressively abolished in the 19th century following the ideals of the French Revolution. This started in Western European countries when the establishment of tolerant governments, such as Napoleon's France and the United Kingdom, encouraged industrious Jews to immigrate. In 1870, after the Papal States were overthrown, the last ghetto in Western Europe was abolished; the walls physically torn down in 1888. In Russia, however, the Jewish Pale continued to exist until the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Venetian Ghetto

The Venetian Ghetto was the area in Venice in which Jewish people were required to live under the government of the Venetian Republic.

Restrictions on their movement and permitted trades varied, but money-lending, running pawnshops, dealing in second hand goods, and tailoring were common occupations. In 1516, they were moved to the area known as the Ghetto Nuovo, Surrounded by canals, this area was linked to the rest of the city by only two bridges, which were closed at night and during certain Christian festivals, when all Jews were required to stay in the Ghetto.

In 1541, the quarter was enlarged to cover the neighboring Ghetto Vecchio, and in 1633, the Ghetto Nuovissimo was also added. Due to population density, buildings rose to six or more stories.

The area is still home to five synagogues connected by a secret corridor. They are known for their interiors, the oldest (Schola Grande Tedesca) dating from 1528. The Scola Spagnola now houses the Museum of Hebrew Art.

Roman Ghetto

The Roman Ghetto was located in the area close to the river Tiber and the Theater of Marcellus in Rome, Italy.

Papal decree Cum nimis absurdum, promulgated by Pope Paul IV in 1555, segregated the Jews in a walled quarter with gates that were locked at night, and subjected them to various restrictions (e.g. limits on permitted professions) and degradations (e.g. compulsory Catholic sermons on the Jewish shabbat), although to a lesser degree than in other European countries. The district lacked a well and flooded every winter.

When Napoleonic forces occupied Rome, the Ghetto was legally abolished, in 1808, but it was reinstated as soon as the Papacy regained control. In 1848, during the brief revolution, the ghetto was abolished once more, again temporarily. The Jews had to petition annually for permission to live there, and were restricted from owning any property, even within the ghetto. They paid an annual tax for the privilege of living there and annually had to swear loyalty to the Pope by the Arch of Titus, which celebrates the Roman sack of Jerusalem.

Pope Leo XIII was less intransigent than Pius IX. The city of Rome was able to tear down the ghetto's walls in 1888 and demolish some houses before the area was reconstructed around the new synagogue.

World War II

The Nazis re-instituted Jewish ghettos in Eastern Europe before and during World War II. However, the nature of these ghettos was dramatically different. Explicit anti-Semitism in Nazi ideology developed into an official state policy requiring Jews to be confined in the ghettos and later shipped to concentration camps. The same policy was instituted in all countries under the Third Reich's control, with most of the Jews confined into tightly packed areas in the cities of Eastern Europe. Some of the more notorious ghettos were in Warsaw, Lublin, Lodz, Tuliszhkow, Radom, Opole, Kielce, Bialystok, and Krakow in Poland, Riga, Vilno, Vitebsk, Pinsk, Lvov, and Smolensk in Russia, and Budapest in Hungary. All social, economic, and legal privileges ceased to exist there and were supplanted by state control.

Starting in 1939, the Nazi regime began moving Polish Jews into designated ghettos in Tuliszkow (in December, 1939), in Lodz (in April, 1940), in Warsaw (in October, 1940), and into many other ghettos throughout 1940 and 1941. The ghettos were walled off, just like in medieval times, except that any Jew found leaving was shot.

The situation in the ghettos was brutal. As the Jews were not allowed out of the ghetto, they had to rely on food supplied by the Nazis. With crowded living conditions, starvation diets, and little sanitation (in the Lodz Ghetto a full 95 percent of the apartments had no sanitation or running water), hundreds of thousands of Jews died of disease and starvation. In 1942, the Nazi government began "Operation Reinhard," which was the systematic deportation of Jews to extermination camps. During the Holocaust, the authorities deported Jews from everywhere in Europe to these ghettos, or directly to the camps. In some ghettos local resistance organizations started uprisings. However, none were successful, and the Jewish population of the ghettos was almost entirely annihilated.

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto was the largest of the Jewish ghettos in World War II. In the three years of its existence, starvation, disease, and deportations to concentration camps dropped the population of this ghetto from an estimated 450,000 to 37,000.

The Warsaw Ghetto was opened on October 16, 1940 to receive about 380,000 people, approximately 30 percent of the population of Warsaw despite being only 2.4 percent of its area. The Nazis then built a wall, effectively closing off the Warsaw ghetto from the outside world on November 16, 1940.

In early 1942, the Nazis began to exterminate the Jews of Europe. The first phase was to eliminate the Jews in Poland. After the construction of extermination camps was completed in July 1942, the wholesale liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto was set to begin.

On January 18, 1943, armed resistance started. There was some initial success, which was followed by three months of fighting. The final battle started on the eve of Passover, April 19, 1943. During the fighting approximately 7,000 Jewish partisans were killed and 6,000 were burned alive or gassed in bunkers. The remaining 50,000 people were sent to German concentration camps.

Lodz Ghetto

The Lodz Ghetto was the second-largest ghetto (after the Warsaw Ghetto) established for Jews in Nazi-occupied Poland. Situated in the town of Lódz, with 672,000 inhabitants and originally intended as a temporary gathering point for Jews, the ghetto was transformed into a major industrial center, providing much needed supplies for Nazi Germany and especially for the German Army. It transformed the Jewish population (reduced from 233,000 to about 164,000) into a slave labor force. Over the years, Jews from Central Europe and as far away as Luxembourg were deported to the ghetto. A small Roma population was also resettled there.

Even though the work was essential to the ghetto's survival, and despite the Third Reich's Armaments Minister Albert Speer advocating the ghetto's continued existence as a source of cheap labor, in the summer of 1944 the final order came to start gradual liquidation of the remaining population. By late August of that year, the last ghetto in Europe was eliminated.

The peculiar situation of the Lódz Ghetto, namely conviction that productivity would ensure survival, coupled with brutal Nazi administration, prevented any manifestations of armed resistance such as in the Warsaw ghetto uprising. However, defensive resistance in the ghetto saved many Jews from final transportation.

Krakow Ghetto

The Jewish ghetto in Kraków (Cracow) was one of the five main ghettos created by the Nazis during their occupation of Poland during World War II. Before the war, Kraków was an influential cultural center for the 60,000-80,000 Jews that resided there. However, in May 1940, the Nazis announced that Kraków should become the "cleanest" city in the General Government and ordered a massive deportation of Jews from the city. Of the more than 68,000 Jews in Kraków, only 15,000 workers and their families, all crammed into 30 streets, 320 residential buildings, and 3,167 rooms, were permitted to remain due to the policy of separating "able workers" from those who would later be exterminated.

The armed underground resistance in the ghetto had some success, but, unlike in Warsaw, their efforts did not lead to a general uprising before the ghetto was liquidated.

From May 30, 1942 onward, the Nazis implemented systematic deportations from the ghetto to surrounding concentration camps. Thousands of Jews were transported over the succeeding months. The final 'liquidation' of the ghetto came in March 13 - March 14, 1943 when 8,000 Jews, deemed able to work, were transported to the Kraków-Płaszów labor camp. Any remaining were killed or sent to die in Auschwitz.

Post-War Ghettos in the World

South African and African ghettos

In South Africa under the apartheid policies, The Group Areas Act of April 27, 1950 barred people of particular races from residing in various urban areas. One of the most notorious “black ghettos” was Soweto, a mostly black urban area to the south west of Johannesburg. During apartheid regime, Soweto was constructed for the specific purpose of housing African people who were then living in areas designated by the government for white settlement, such as the multi-racial area called Sophiatown. Today, Soweto is among the poorest parts of Johannesburg. However, there have been signs of economic improvement, and Soweto has become a center of nightlife.

There are other "ghettos" in South Africa, such as KwaMashu in Durban in the KZN province. Resettlements, comparable to forced deportations in Poland, into specific, ghetto-like areas were quite common elsewhere in Africa, especially along the Zambezi River. Before the Kariba Dam was constructed in 1956, whole tribes were forcibly moved into economically inhospitable inland areas.

Ghettos in the United States

In the United States, during the period between the abolition of slavery and the passing of the civil rights laws in the 1960s, discriminatory notions, sometimes codified in law, forced many urban African Americans to live in specific neighborhoods, such as Bronzeville in Chicago and Harlem in New York City, which became known as "ghettos." The Civil Rights Act allowed wealthier African Americans to move to formerly all-white areas. The result of this was that the economic bases of many ghettos collapsed, leaving them as zones of below-average income, poorly-maintained housing, and high crime. For example, by the 1970s, the Robert Taylor Homes, located in Chicago's Bronzeville, was home to the poorest and third-poorest census tracts in the United States.

The formation of the ghettos and the black underclass forms one of most controversial issues in sociology. One of the earliest studies of the modern phenomenon of ghetto formation was Daniel Patrick Moynihan's 1965 work The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, often referred to as the "Moynihan Report." This report noted that the number of black welfare cases was rising, while employment was falling. It also pointed out that a quarter of all black children were born to unmarried women, and that this percentage was rising. The ghetto was described as a "tangle of pathologies," and Moynihan predicted that conditions would only worsen.

In the 1980s, a revival of all "ghetto-encompassing" questions occurred, as well as the development of new theories on why these ghettos emerged. Charles Murray argued in Losing Ground that "Great Society" liberalism created the hopeless poor. Murray claimed that the eligibility of single women for welfare encouraged women to have babies out of wedlock, and that welfare discouraged all from working. Murray concluded his book with a call for the abolition of welfare. On the other hand, William Julius Wilson argued in The Truly Disadvantaged that easy access to welfare had little effect on women's decisions on childbearing. Wilson claimed, instead, that the flight of low-skilled manufacturing jobs to the suburbs and the Southern states left blacks economically isolated in the ghettos due to their "spatial mismatch." Wilson thus explained the high percentage of out-of-wedlock births by the lack of "marriageable" (i.e. employed and single) men.

Yet another theory of ghetto formation was offered by Roger Waldinger in Still the Promised City?, which detailed a mismatch between the wages that blacks desire and the wages which low-skilled jobs actually pay. In looking at New York City, Waldinger pointed out that new immigrants living in similar “ghettos” (Koreans, Chinese, Pakistanis, Dominicans, etc.) often fared better than American-born blacks. Waldinger also noticed that southern-born and Caribbean-born blacks had higher incomes than northern-born blacks. Waldinger argued that immigrant groups benefited by establishing nepotistic niches for themselves, and used niches for mutual help, something blacks in most cases were unable to do. Waldinger also noted that even though hotels and restaurants may offer very low wages, they still outclass wages in Mexico, rural China, or Africa. Thus, immigrants readily accept them. By contrast, unskilled northern-born blacks, who hope to do something better than their parents, disdain these jobs and may often wind up working outside the legitimate economy.

Thus, despite various attempts to improve social and economic conditions, although the legal arbitrariness practically disappeared in post-1964 American ghettos, the ghetto attributes of social ostracism and economic hardship are still generally held. In terms of the security aspect, apart from addressing the alarmingly high crime rate, there has not been any state intrusion into life in these ghettos whatsoever, meaning that residents are not legally or physically restricted from leaving. This constitutes the specifically "American way" of ghetto life, which differs from that found in other parts of the world.

While the American “melting pot” lessened the importance of ethnic origin, culture, and religion—although some of it returned as “ethnic profiling” after 9/11—quite different situations developed in Europe.

European Ghettos

Based on the four definitional attributes, ghettos exist in most, if not all, of the industrialized European countries even in the twenty-first century. There are, of course, no more Jewish ghettos. Contemporary European problems involve visible minorities, namely recent, and second, if not third, generation immigrants.

In France, the poorer banlieues, or suburbs, especially those of Paris, house an impoverished population, largely of North African Muslim and black African origin, in large high-rise building developments known as Cités. These were built in the 1960s and 1970s in the industrial suburbs to the north and east of Paris, especially in the Seine-St-Denis area, as well as in other French cities like Villeurbanne near Lyon. They are similar in style to the large, inner-city, urban renewal projects in the United States, such as the former Cabrini Green in Chicago, and have similar problems. Though most of the young people were born in France, and are citizens, this North-African and African population has suffered routine discrimination in the job market as well as by the police. The 2005 riots in France originated within these ghettos as a reaction to legal discrimination and the attitude of French society that the minorities in ghettos threaten their secularism. Thus, although the generally poor economic situation aggravated social hardship, it was mostly the legal and security attributes that incited the unrest. On the other hand, most of the recent African immigrants, from places such as Cote d'Ivoire and Dakar, Senegal, prefer the biased, but functioning, legal system in the French ghettos over the complete breakdown and chaos in their home countries.

In Germany, the “post-war economic miracle” happened with considerable help from Turkish immigrants. They came, officially invited in, to boost a much-needed labor force in the heavy machinery sectors and, as in France, they settled in ghettos. They did not seem to mind, and certainly their social, economic and overall way of life dramatically improved, as long as the “economic miracle” lasted. With increasing unemployment in the machinery sector and other industries, the state had to step in and, to preempt riots, offered the Turkish families reasonable settlements if they returned to their homeland.

Roma Problem: Czech Republic and Slovakia

Roma, or Gypsies—with their basically nomadic way of life, their reluctance to stay and try to become assimilated into any one country, their absence of a common language, and their lack of marketable skills—have caused problems for Eastern and Central European governments for centuries. Their nomadic way of life saved them from being put into ghettos (or worse still, concentration camps) until after the Second World War. Then, the Eastern European states were forced to act. They categorized the Roma as a "social group" or "problem" and thus legitimized intrusive state intervention to deal with them.

Another aspect of this redefinition of Roma identity was the transformation of their ethnic and cultural difference into social deviance. Roma children who did not speak the host language very well were treated as mentally deficient and put into special classes within which they could advance only to the fourth grade. Young Roma thus became increasingly alienated and isolated from the host society, experiencing an enforced "social retardation," which led to withdrawal, aggression, and other forms of antisocial behavior. Perhaps the most radical instance of such intervention was the policy of sterilization adopted by the Slovak government between 1980 and 1990 to curb what it called "unhealthy high fertility rates" among the Roma.

After the Communist regimes ended in Eastern Europe, prejudice towards the Roma increased. For example, a 1991 Times Mirror survey found that Europeans in overwhelming numbers expressed contempt for Roma: 59 percent of Germans, 91 percent of Czechoslovaks, 71 percent of Bulgarians, 79 percent of Hungarians, and 50 percent of Spaniards. Other polls showed similar negative views of Roma.

By the end of the twentieth century, Roma ghettos had appeared in the Czech Republic. The Roma moved there, both voluntarily and involuntarily, when municipalities forcibly relocated them from other areas. The majority of those living there are unemployed and uneducated, and the crime rate is high. As the ghetto develops, non-Roma people move away. The most infamous ghetto in the Czech Republic is Chánov, in the city of Most.

In the case of the Roma, all four ghetto attributes are in evidence: they have a tentative legal status, social and economic hardships are on the rise, and they are relocated into ghettos by the state, allegedly to protect them from the prejudice and harassment of the society, but in reality to deal with a problem to which they have no other solution.

Cultural Life and the Ghetto

It is often said that great art is born out of suffering, and so it is not necessarily a coincidence that great artists lived, and still live, in ghettos. Ghettos often became known as vibrant cultural centers, for example Harlem in New York in the 1920s and 1930s. Artists such as Bob Marley, Ice Cube, John Lee Hooker, Cab Calloway, and Tupac Shakur were born and raised in ghettos, and much of their music comes from their own suffering, experiences, and life in the ghetto.

Even in Nazi-run ghettos during the Second World War cultural events did take place: lectures, concerts, theater, and art exhibits. In many cases, the artists and performers were prominent figures in Polish cultural life. Movie director Roman Polanski, a survivor of the ghetto, recalled his experience in his memoirs, Roman. In the Theresienstadt ghetto, in the fortress of Terezín in former Czechoslovakia, the inhabitants formed orchestras as well as chamber groups and jazz ensembles. Several stage performances were produced and attended by camp inmates, although they were often coerced into performing by the Nazis for propaganda purposes. Many of the composers and other artists were subsequently sent to Auschwitz where they died in the gas chambers. Karel Ancerl escaped this fate, although his family did not, becoming a world-renowned conductor of the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra and later the Toronto Symphony Orchestra.

It is acknowledged that the "renaissance," and even the "golden era," of Czech and Slovak literature of the post-war period occurred during the 1970s and 1980s in Czechoslovakia under the Communist regime. There, several hundred intellectuals (writers, scientists and artists), who signed the anti-communist proclamation “Chartist Movement,” suffered at the hands of the Czech State Security Police. They lost their jobs, were forbidden to publish or exhibit their work, were shadowed by agents constantly, and, hence, ostracized by the general public because of the police presence. All the definitional properties of the classic ghetto were in force, and they even used the term themselves to describe their situation. And yet, the best works by writer Ludvik Vaculik, by playwrights Pavel Kohout and former Czech president, Vaclav Havel, by scientist Vaclav Cerny, and many others, were done during this “ghetto period.”

Conclusion

The occasional eruption of artistic flourishing notwithstanding, the most significant feature of ghettos is the cold and inhuman logic that led to their creation. In each case, the purpose was to move a minority, deemed troublesome to the authorities, within protective walls, real or virtual, without any legal recourse. Those authorities used all means—killing included—to prevent residents inside the ghetto from emerging back into the general society. The magnitude of moral reprehensibility for such intolerant policies, that led to inhumane and eventually murderous acts, was not evident to the those responsible for the creation and enforcement of ghettos. The realization of a peaceful world of prosperity for all can only happen when the establishment, and continued presence, of ghettos are no longer deemed justifiable.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Murray, Charles. 1984. Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950-1980. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0465042317

- Polanski, Roman. 1984. Roman. New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0688026214

- Silverman, Carol. 1995. "Persecution and Politicization: Roma (Gypsies) of Eastern Europe." Nationalism in Eastern Europe 19.2. Retrieved April1 14, 2023.

- Waldinger, Roger. 1996. Still the Promised City? : African-Americans and New Immigrants in Postindustrial New York. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674838610

- Wilson, William Julius. 1990. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226901319

External links

All links retrieved April 14, 2023.

- Kraków Ghetto history Death Camps

- Ghettos: The Lódz Ghetto Jewish virtual library

- Warsaw Ghetto Liquidation Death Camps

- Holocaust Ghettos: The Warsaw Ghetto Jewish virtual library

- Theresienstadt Music and the Holocaust

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ghetto history

- Roman_Ghetto history

- Venetian_Ghetto history

- Warsaw_Ghetto history

- Lodz_Ghetto history

- Krakow_Ghetto history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.