Beauty

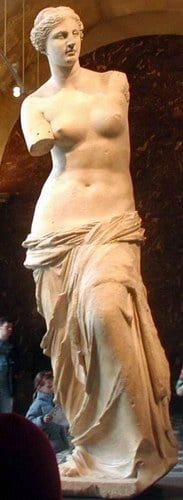

Beauty is commonly defined as a characteristic present in objects such as nature, art work, and a human person that provides a perceptual experience of pleasure, joy, and satisfaction to the observer, through sensory manifestations such as shape, color, and personality. Beauty thus manifested usually conveys some level of harmony amongst components of an object.

According to traditional Western thought from the antiquity until the Middle Ages, beauty is a constitutive element of the cosmos associated with order, harmony, and the mathematical there. Philosophers in that tradition treated and conceived beauty along with truth, goodness, love, being, and the divine. Thus the study of beauty was an integral part of the study of the whole cosmos.

The study of beauty made a major shift with modern philosophy. Modern philosophers shifted the study of beauty from the ontological sphere to that of human faculties. Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten (1714-1762) coined aesthetics which literary meant a study of human sensibility. With this turn, beauty was dissociated from other ontological components such as truth, goodness, love, being, and the divine. Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) was the first major philosopher who developed the study of beauty as an autonomous discipline. The philosophical study of beauty and arts is aesthetics, and it covers a wide range of subjects including concepts, values, and experiences of beauty in artistic activities.

With the aesthetic shift in modern philosophy, at least two new issues arose: 1) more appreciation of the contribution of the subject for a judgment of beauty than Greek and Medieval philosophers, and 2) less emphasis on moral beauty in the overall picture of beauty than Greek and Medieval philosophers. Perhaps, the first issue was a desirable trend because what we normally experience is that the determination of beauty is derived from some kind of interaction between subject and object, and not from the object of beauty alone. The second issue can remind us that perhaps the old metaphysical tradition of Greek and Medieval thinkers correctly understood the importance of moral beauty as the Far Eastern tradition basically converges with it in this matter.

History of the Philosophy of Beauty

Beauty has been recognized as one of the core values throughout history, and in diverse cultural traditions. While beauty has cross-historical and cross-cultural recognition, the sense and the standard of beauty differ from one period to another, also from one cultural tradition to another.

Ancient Greek philosophy

The Greek word kalos ("beautiful") was used in ancient Greek societies, not only for the descriptions of sensibly beautiful things but also morally admirable characters and conducts, noble birth, high social status, and technically useful things. The Greek word kalokagatia ("beauty-good"), combining two terms "beauty" and "good," was a natural combination in the Greek context. Greek philosophy was built upon the presupposition that happiness (eudaimonia) is the highest good. Eudaimonism formed the general contexts. Philosophers presented different views for the interpretation of what happiness is and the method of achieving it, but shared the same conviction for this ultimate goal of life. Accordingly, issues of beauty were also discussed, and how beauty could contribute to the highest good of human life. Beauty was naturally discussed in association with truth and goodness, which pointed to the divine. The study of beauty was not an autonomous discipline and it was not "aesthetics" in the sense of a "study of human sensibility" which emerged after Kant.

- Pythagoras and Pythagoreans

Pythagoras and Pythagoreans, Pre-Socratic philosophers understood that harmony is an objectively existing principle that constitutes the cosmos as a unified body. While harmony is built upon mathematical order and balance, beauty exists as the objective principle in beings which maintain harmony, order, and balance. They realized that aesthetic experiences in arts such as music are closely tied to mathematical ratios of tones and rhythms.

Pythagoras and Pythagoreans understood experiences of beauty and contemplations of the mathematical as central part of their religious exercises to purify the soul. Aesthetic experiences and exercises of reason were understood as an integral part of religious practices, a necessary process and training to cultivate the soul, which they understood as immortal. They built a theory of beauty within the framework of their religious thought. Their conviction of the immortality of the soul, the relationship between the mathematical and the beautiful, gave a strong impact on Plato.

- Plato

Plato (c.428–c.348 B.C.E.) conceived beauty along with "good," "justice," etc. as eternal, immutable, divine existence. As Ideas they are not mental images or psychological objects of mind, but are objectively existing, unchanging, permanent, and eternal beings. They belong to a divine realm. For Plato, the Idea of beauty exists in a perfect form for eternity in the realm of immortal gods. Ideas such as the Idea of beauty are manifested in imperfect forms in the material world we live in. Plato referred to the world we live in as a "shadow" of the perfect world of Ideas. The subject on beauty was built into Plato’s metaphysics.

Human souls are immortal. Every human being is born with implicit understanding of the Idea of beauty and all other Ideas. Upon entering into the body at birth, a human being temporarily "forgets" these Ideas. Throughout his/her life course, he/she seeks to familiarize himself/herself with these Ideas. This process is a recollection of Ideas the soul has temporarily forgotten.

The process of ascent through the experience of beauty begins with beauty manifested in human bodies. It is gradually elevated to the beauty in the soul, characters, and other incorporeal realms. Beauty manifested in bodies and physical materials is less perfect for Plato, and the soul is naturally led to seek permanent and perfect beauty. For Plato, the power of eros is the driving force for the quest of perfect Ideas in humans.

Plato conceived the Idea of good as the supreme one, and all other Ideas including that of beauty exist under it. In his ontology, beauty, good, truth, and other virtues and being are all tied together. Accordingly, "to be beautiful," "to be virtuous," and "to have true knowledge" are inseparable.

Plotinus (205-270 C.E.), who developed the Neo-Platonic tradition, also held that good and beauty are one in the realm of thought, and that the soul must be cultivated to see good and beauty. In both Platonic and Neo-Platonic traditions, concepts of "being," "good," and "beauty" are always understood to be inseparable. The experience of beauty is therefore also inseparable from that of being and good.

- Aristotle

Unlike Plato, Aristotle (384-322 B.C.E.) conceived beauty not as an immutable, permanent being existing above the world we live in, but as a property of nature and the works of art. While tying beauty with the good, Aristotle also made a conceptual distinction between them.

Aristotle developed a theory of art and presented it as part in his Poetics, but his ideas and discussions on beauty and arts are scattered in diverse works including Metaphysics, Nichomachean Ethics, Physics, and Rhetoric. He focused more on examining existing forms of arts and developing art theories.

Medieval philosophy

As a Christian thinker, St. Augustine (354-430) ascribed the origin of beauty, good, and being to the Creator God. Beauty as well as goodness and existence come from the Creator alone. The Platonic unity of beauty, goodness, being, perfection, and other virtues is found in Augustine. Rational understanding of the order and harmony of the cosmos, recognizing the beauty, was the soul's process of purification and path of ascent to the divine realm.

Thomas Aquinas (c.1225-1274) distinguished beauty and good in terms of meaning (ratio), but he identified them as the same being (subjectum), indistinguishable in reality. Since God is the only source of beauty, good, and being, they are said to be in oneness. He enumerated elements of beauty: perfection (integritas sive perfectio), harmony (debita proportion sive consonantia), and clarity (claritas).

Modern and contemporary philosophy

After Christian thought receded from the mainstream of philosophy, the discussion of beauty also shifted from its metaphysical treatment to the studies of our perception of beauty. With and after the Renaissance, arts flourished and beauty was discussed in relation to our capacities in the arts. Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten in the eighteenth century coined "aesthetics" for the studies of human sensibility (aesthesis). The concept of "sublime" was also discussed in relation to morality.

Prior to the publication of the Critique of Pure Reason (1781), his major work on epistemology, Kant wrote Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and The Sublime (1764). However, it was by writing the Critique of Judgment (1790) that he established the philosophy of art as an independent genre. The Critique of Pure Reason, the Critique of Practical Reason (1788), and the Critique of Judgment, respectively, discussed the three domains of nature, freedom, and art through the analyses of three faculties of the mind: cognition, desire, and feeling. The analysis of beauty now became one of the major independent branches of philosophy comparable to epistemology and ethics, although for both Greeks and Medievalists, the area of beauty and art was not an independent or autonomous area of study.

The focus of the studies of beauty made a shift from the beauty of nature to that of the arts after Kant. German Romantics such as Goethe, Schiller, and Holderlin and German philosophers such as Schelling and Hegel further developed philosophies of arts. Studies of beauty in German Idealism reached a peak with Schelling, and Hegel approached arts from a historical perspective.

After Hegel, studies of beauty were further dissociated from metaphysics, and arts were also separated from the traditional concept of beauty. In the twentieth century, however, metaphysical discussions of beauty were revived by Heidegger and Gadamer. The philosophy of beauty and arts today is one of important branches of philosophy.

Far Eastern Thought

Far Eastern thought has three major traditions: Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. These traditions were intertwined, forming a general background within which their experiences and concepts of beauty were formed.

Unlike in the traditions of Western philosophy, any abstract theory of beauty was not sufficiently developed in these traditions. Beauty was often discussed within ethical (Confucianism) and cosmological (Taoism) contexts.

The Chinese character of beauty (美) consists of the components of "sheep" (羊) and "big" or "great" (大). As Confucius described in Analects, a sheep is an animal offered at religious rituals as an offering to Heaven. Beauty thus means "great sacrifice" which connotes "self-sacrifice." Traditional virtues such as filial piety and loyalty involve this self-sacrifice and therefore were considered to be noble and beautiful. Beauty is therefore often ascribed to virtuous actions, characters, and life style. By the way, the Chinese characters of good (善) and justice (義) similarly contain the component of "sheep" (羊).

Beauty was also understood as a part of nature. Nature is the totality of the cosmos which encompasses human life as well. "To be natural" means "to be authentic." In Taoism in particular, ethics and cosmology were fused into naturalism. Beauty was understood as a natural part of the cosmos and the norm of human behavior.

Theories of beauty in Far Eastern traditions were not a general theory of beauty but particular theories in each form of arts. The practical orientation of Chinese tradition probably led studies of beauty not into speculative metaphysics but into practical theories in each form of arts.

Issues on Beauty

Subjective and Objective Elements in Beauty

Greeks and Medieval Christians understood beauty to be primarily what exists objectively in the world, tracing it in the divine realm. It is in this context that Thomas Aquinas' celebrated arguments for God's existence "from degrees of perfection" and "from design" can be understood. With the emergence of aesthetics in modern philosophy, however, the role of the subject in perceiving beauty became an important matter. Aesthetics was meant to discuss about how an individual's sensuous perception as a subject occurs in judging beauty. Kant discussed aesthetic judgments of beauty in terms of an individual's subjective feelings, although they are not purely subjective as Kant had them claim universal validity. One reason why Kant wanted to avoid the Greek and Medieval objectivist approach was that he was critical towards the Thomistic arguments for God's existence. Far more subjectivist than Kant were his contemporaries such as David Hume (1711-1776) and Edmund Burke (1729-1797), according to whom beauty is subjective in that it largely depends on the attitude of the observer. Baumgarten and G. E. Lessing (1729-1781), by contrast, tended to be objectivist.

While it is true that the object does contain physical elements of beauty that are in harmony, it is also true that the object alone cannot determine the value of beauty. The determination of beauty involves also the subject who has a certain attitude and pre-understanding. Kant is considered to have mediated between the objectivist and subjectivist positions mentioned above. His Critique of Judgment explains this in terms of the "free play" or "free harmony" between imagination and understanding. This free play constitutes a feeling of "disinterested" pleasure in a non-conceptual, if empirical, state of mind. Although Kant's use of the term "disinterested" may invite some questions, his realization that a judgment of beauty results from both subject and object "is probably the most distinctive aspect of his aesthetic theory."[1]

Moral Beauty

Although it is true that objectivism alone cannot work well as a theory of beauty, its classical version amongst Greeks and Medieval Christian thinkers seems to have had one strength among others: an encompassing view of objective beauty that covers beauty in nature and art and moral beauty together. In this sense, classical objectivism interestingly converges with Far Eastern thought. Of course, classical Western objectivism in referring to moral beauty as individual virtues such as prudence, fortitude, and temperance, may differ from Far Eastern thought that primarily focuses on relationships in a family or society such as filial piety (moral beauty shown by a child to its parents), fidelity/chastity (moral beauty from wife towards husband), and loyalty (moral beauty displayed by an individual to a superior). But, these individual virtues and family/group virtues overlap without any gap. Various kinds of moral beauty or goodness seem to be even more important than beauty in nature and art because they lead us to come closer to the divine realm than natural beauty and beauty in art (Greek and Medieval) or more directly reflect heaven (Far Eastern). According to French philosopher Victor Cousin (1792-1867), who inherited the tradition of ancient Greek philosophy, "Moral beauty is the basis of all true beauty."[2]

Notes

- ↑ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Kant's Aesthetics and Teleology." Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ↑ Giga Quotes, "Victor Cousin". Retrieved August 22.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Eco, Umberto. History of Beauty Rizzoli Aesthetics, 2004

- --------, Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages Yale University Press, 2002

- Feagin, Susan L. and Patrick Maynard, Aesthetics Oxford University Press, 1998

- Hofstadter, Albert. and Richard Kuhns Philosophies of Art & Beauty, The University of Chicago Press, 1964

- Navone, John. Enjoying God's Beauty, The Liturgical Press, 2003