Industrial Workers of the World

| Industrial Workers of the World | |

| Founded | 1905 |

|---|---|

| Members | 2,000/900 (2006) 100,000 (1923) |

| Country | International |

| Office location | Cincinnati, Ohio |

| Website | www.iww.org |

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or the Wobblies) is an international union currently headquartered in Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. At its peak in 1923, the organization claimed some 100,000 members in good standing, and could marshal the support of perhaps 300,000 workers. Its membership declined dramatically after a 1924 split brought on by internal conflict and government repression. Today it is actively organizing and numbers about 2,000 members worldwide, of whom roughly half (approximately 900) are in good standing (that is, have paid their dues for the past two months). IWW membership does not require that one work in a represented workplace, nor does it exclude membership in another labor union.

The IWW contends that all workers should be united within a single union as a class and that the wage system should be abolished. They may be best known for the Wobbly Shop model of workplace democracy, in which workers elect recallable delegates, and other norms of grassroots democracy (self-management) are implemented.

History of the IWW 1905-1950

| Part of a series on Organized Labor |

|

| The Labor Movement |

| New Unionism · Proletariat |

| Social Movement Unionism |

| Syndicalism · Socialism |

| Labor timeline |

| Labor Rights |

| Child labor · Eight-hour day |

| Occupational safety and health |

| Collective bargaining |

| Trade Unions |

| Trade unions by country |

| Trade union federations |

| International comparisons |

| ITUC · WFTU · IWA |

| Strike Actions |

| Chronological list of strikes |

| General strike · Sympathy strike |

| Sitdown strike · Work-to-rule |

| Trade Unionists |

| Sidney Hillman · I. C. Frimu |

| I. T. A. Wallace-Johnson |

| Tanong Po-arn |

| A. J. Cook · Shirley Carr |

| Academic Disciplines |

| Labor in economics |

| Labor history (discipline) |

| Industrial relations |

| Labor law |

Founding

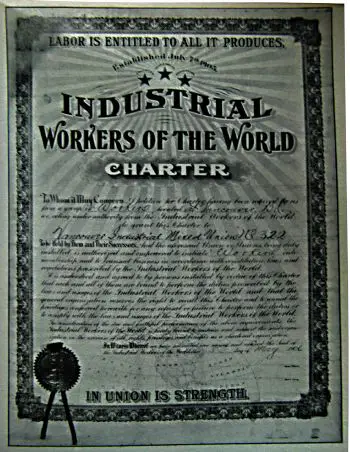

The IWW was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the Western Federation of Miners) who were opposed to the policies of the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

The convention, which took place on June 27, 1905, in Chicago, was then referred to as the "Industrial Congress" or the "Industrial Union Convention"—it would later be known as the First Annual Convention of the IWW. It is considered one of the most important events in the history of industrial unionism and of the American labor movement in general.

The IWW's first organizers included Big Bill Haywood, Daniel De Leon, Eugene V. Debs, Thomas J Hagerty, Lucy Parsons, Mary Harris Jones (commonly known as "Mother Jones"), William Trautmann, Vincent Saint John, Ralph Chaplin, and many others.

The IWW's goal was to promote worker solidarity in the revolutionary struggle to overthrow the employing class; its motto was "an injury to one is an injury to all," which expanded upon the 19th century Knights of Labor's creed, "an injury to one is the concern of all." In particular, the IWW was organized because of the belief among many unionists, socialists, anarchists and radicals that the American Federation of Labor not only had failed to effectively organize the U.S. working class, as only about 5 percent of all workers belonged to unions in 1905, but also was organizing according to narrow craft principles which divided groups of workers. The Wobblies believed that all workers should organize as a class, a philosophy which is still reflected in the Preamble to the current IWW Constitution:

The working class and the employing class have nothing in common. There can be no peace so long as hunger and want are found among millions of the working people and the few, who make up the employing class, have all the good things of life. Between these two classes a struggle must go on until the workers of the world organize as a class, take possession of the means of production, abolish the wage system, and live in harmony with the Earth. … Instead of the conservative motto, "A fair day's wage for a fair day's work," we must inscribe on our banner the revolutionary watchword, "Abolition of the wage system." It is the historic mission of the working class to do away with capitalism.[1]

The Wobblies differed from other union movements of the time by its promotion of industrial unionism, as opposed to the craft unionism of the American Federation of Labor. The IWW emphasized rank-and-file organization, as opposed to empowering leaders who would bargain with employers on behalf of workers. This manifested itself in the early IWW's consistent refusal to sign contracts, which they felt would restrict the only true power that workers possessed: The power to strike. Though never developed in any detail, Wobblies envisioned the general strike as the means by which the wage system would be overthrown and a new economic system ushered in, one which emphasized people over profit, cooperation over competition.

One of the IWW's most important contributions to the labor movement and broader push towards social justice was that, when founded, it was the only American union to welcome all workers including women, immigrants, and African Americans into the same organization. Indeed, many of its early members were immigrants, and some, like Carlo Tresca, Joe Hill, and Mary Jones, rose to prominence in the leadership. Finns formed a sizable portion of the immigrant IWW membership. "Conceivably, the number of Finns belonging to the I.W.W. was somewhere between five and ten thousand."[2] The Finnish-language newspaper of the IWW, Industrialisti, published out of Duluth, Minnesota, was the union's only daily paper. At its peak, it ran 10,000 copies per issue. Another Finnish-language Wobbly publication was the monthly Tie Vapauteen ("Road to Freedom"). Also of note was the Finnish IWW educational institute, the Work People's College in Duluth, and the Finnish Labour Temple in Port Arthur, Ontario which served as the IWW Canadian administration for several years. One example of the union's commitment to equality was Local 8, a longshoremen's branch in Philadelphia, one of the largest ports in the nation in the WWI era. Led by the African American Ben Fletcher, Local 8 had over 5,000 members, the majority of whom were African American, along with more than a thousand immigrants (primarily Lithuanians and Poles), Irish Americans, and numerous others.

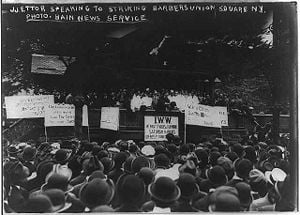

The IWW was condemned by politicians and the press, who saw them as a threat to the status quo. Factory owners would employ means both non-violent (sending in Salvation Army bands to drown out speakers) and violent to disrupt their meetings. Members were often arrested and sometimes killed for making public speeches, but this persecution only inspired further militancy.

Political action or direct action?

Like many leftist organizations of the era, the IWW soon split over policy. In 1908, a group led by Daniel DeLeon argued that political action through DeLeon's Socialist Labor Party was the best way to attain the IWW's goals. The other faction, led by Vincent Saint John, William Trautmann, and Big Bill Haywood, believed that direct action in the form of strikes, propaganda, and boycotts was more likely to accomplish sustainable gains for working people; they were opposed to arbitration and to political affiliation. Haywood's faction prevailed, and De Leon and his supporters left the organization.

Organizing

The IWW first attracted attention in Goldfield, Nevada in 1906 and during the strike of the Pressed Steel Car Company[3] at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, in 1909. Further fame was gained later that year, when they took their stand on free speech. The town of Spokane, Washington, had outlawed street meetings, and arrested Elizabeth Gurley Flynn,[4] a Wobbly organizer, for breaking the ordinance. The response was simple but effective: When a fellow member was arrested for speaking, large numbers of people descended on the location and invited the authorities to arrest all of them, until it became too expensive for the town. In Spokane, over 500 people went to jail and four people died. The tactic of fighting for free speech to popularize the cause and preserve the right to organize openly was used effectively in Fresno, Aberdeen, and other locations. In San Diego, although there was no particular organizing campaign at stake, vigilantes supported by local officials and powerful businessmen mounted a particularly brutal counter-offensive.

By 1912, the organization had around 50,000 members, concentrated in the Northwest, among dock workers, agricultural workers in the central states, and in textile and mining areas. The IWW was involved in over 150 strikes, including those in the Lawrence textile strike (1912), the Paterson silk strike (1913), and the Mesabi range (1916). They were also involved in what came to be known as the Wheatland Hop Riot August 3, 1913

Between 1915 and 1917, the IWW's Agricultural Workers Organization (AWO) organized hundreds of thousands of migratory farm workers throughout the midwest and western United States, often signing up and organizing members in the field, in railyards and in hobo jungles. During this time, the IWW became synonymous with the hobo; migratory farmworkers could scarcely afford any other means of transportation to get to the next job site. Railroad boxcars, called "side door coaches" by the hobos, were frequently plastered with silent agitators from the IWW. The IWW red card was considered the ticket necessary to ride the rails. Workers often won better working conditions by using direct action at the point of production, and striking "on the job" (consciously and collectively slowing their work). As a result of Wobbly organizing, conditions for migratory farm workers improved enormously.

Building on the success of the AWO, the IWW's Lumber Workers Industrial Union (LWIU) used similar tactics to organize lumberjacks and other timber workers, both in the Deep South and the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada, between 1917 and 1924. The IWW lumber strike of 1917 led to the eight-hour day and vastly improved working conditions in the Pacific Northwest. Even though mid-century historians would give credit to the U.S. Government and "forward thinking lumber magnates" for agreeing to such reforms, an IWW strike forced these concessions[5]

From 1913 through the mid-1930s, the IWW's Marine Transport Workers Industrial Union, proved a force to be reckoned with and competed with AFL unions for ascendance in the industry. Given the union's commitment to international solidarity, its efforts and success in the field come as no surprise. As mentioned above, Local 8 was led by Ben Fletcher, who organized predominantly African-American longshoremen on the Philadelphia and Baltimore waterfronts, but other leaders included the Swiss immigrant Waler Nef, Jack Walsh, E.F. Doree, and the Spanish sailor Manuel Rey. The IWW also had a presence among waterfront workers in Boston, New York City, New Orleans, Houston, San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Eureka, Portland, Tacoma, Seattle, Vancouver, as well as in ports in the Caribbean, Mexico, South America, Australia, New Zealand, Germany, and other nations. IWW members played a role in the 1934 San Francisco general strike and the other organizing efforts by rank-and-filers within the International Longshoremen's Association up and down the West Coast.

Wobblies also played a role in the sit-down strikes and other organizing efforts by the United Auto Workers in the 1930s, particularly in Detroit, though they never established a strong union presence there.

Where the IWW did win strikes, such as at Lawrence, they often found it hard to hold onto their gains. The IWW of 1912 disdained collective bargaining agreements and preached instead the need for constant struggle against the boss on the shop floor. It proved difficult, however, to maintain that sort of revolutionary elán against employers; In Lawrence, the IWW lost nearly all of its membership in the years after the strike, as the employers wore down their employees' resistance and eliminated many of the strongest union supporters.

Government repression

The IWW's efforts were met with violent reactions from all levels of government, from company management and their agents, and groups of citizens functioning as vigilantes. In 1914, Joe Hill (Joel Hägglund) was accused of murder and, despite only circumstantial evidence, was executed by the state of Utah in 1915. On November 5, 1916, at Everett, Washington a group of deputized businessmen led by Sheriff Donald McRae attacked Wobblies on the steamer VERONA, killing at least five union members (six more were never accounted for and probably were lost in Puget Sound). Two members of the police force—one a regular officer and another a deputized citizen from the National Guard Reserve—were killed, probably by "friendly fire."[6][7] There were reports that the deputies had fortified their courage with alcohol.

Many IWW members opposed United States participation in World War I. The organization passed a resolution against the war at its convention in November of 1916.[8] This echoed the view, expressed at the IWW's founding convention, that war represents struggles among capitalists in which the rich become richer, and the working poor all too often die at the hands of other workers.

An IWW newspaper, the Industrial Worker, wrote just before the U.S. declaration of war: "Capitalists of America, we will fight against you, not for you! There is not a power in the world that can make the working class fight if they refuse." Yet when a declaration of war was passed by the U.S. Congress in April of 1917, the IWW's general secretary-treasurer Bill Haywood became determined that the organization should adopt a low profile in order to avoid perceived threats to its existence. The printing of anti-war stickers was discontinued, stockpiles of existing anti-war documents were put into storage, and anti-war propagandizing ceased as official union policy. After much debate on the General Executive Board, with Haywood advocating a low profile and GEB member Frank Little championing continued agitation, Ralph Chaplin brokered a compromise agreement. A statement was issued that denounced the war, but IWW members were advised to channel their opposition through the legal mechanisms of conscription. They were advised to register for the draft, marking their claims for exemption "IWW, opposed to war."[9]

In spite of the IWW moderating its vocal opposition, the mainstream press and the U.S. Government were able to turn public opinion against the IWW. Frank Little, the IWW's most outspoken war opponent, was lynched in Butte, Montana in August of 1917, just four months after war had been declared.

The government used World War I as an opportunity to crush the IWW. In September 1917, U.S. Department of Justice agents made simultaneous raids on forty-eight IWW meeting halls across the country. In 1917, one hundred and sixty-five IWW leaders were arrested for conspiring to hinder the draft, encourage desertion, and intimidate others in connection with labor disputes, under the new Espionage Act; one hundred and one went on trial before Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis (the future Commissioner of Major League Baseball) in 1918.

They were all convicted—even those who had not been members of the union for years—and given prison terms of up to twenty years. Sentenced to prison by Judge Landis and released on bail, Haywood fled to the Soviet Union where he remained until his death.

In his 1918 book, The Land That Time Forgot, Edgar Rice Burroughs presented an IWW member as a particularly despicable villain and traitor. A wave of such incitement led to vigilante mobs attacking the IWW in many places, and after the war the repression continued. In Centralia, Washington, on November 11, 1919, IWW member and army veteran Wesley Everest was turned over to the lynch mob by jail guards, had his teeth smashed with a rifle butt, was castrated, lynched three times in three separate locations, and then his corpse was riddled with bullets before it was disposed of in an unmarked grave.[10] The official coroner's report listed the victim's cause of death as "suicide."

Members of the IWW were prosecuted under various State and federal laws and the 1920 Palmer Raids singled out the foreign-born members of the organization. By the mid-1920s membership was already declining due to government repression and it decreased again substantially during a contentious organizational schism in 1924 when the organization split between the "Westerners" and the "Easterners" over a number of issues, including the role of the General Administration (often oversimplified as a struggle between "centralists" and "decentralists") and attempts by the Communist Party to dominate the organization. By 1930, membership was down to around 10,000.

One result of the Palmer Raids was the confiscation of Joe Hill's ashes, among other items taken from IWW offices. These ashes were recovered under the Freedom of Information Act in the late 1980s.

Activity after World War II

The Wobblies continued to organize workers and were a major presence in the metal shops of Cleveland, Ohio until the 1950s. After the passage of the Taft-Hartley Act in 1950 by the U.S. Government, which called for the removal of communist union leadership, the IWW experienced a loss of membership as differences of opinion occurred over how to respond to the challenge. The Cleveland IWW metal and machine workers wound up leaving the union, resulting in a major decline in membership once again.

The IWW membership fell to its lowest level in the 1950s, but the 1960s Civil Rights Movement, anti-war protests, and various university student movements brought new life to the IWW, although with many fewer new members than the great organizing drives of the early part of the twentieth century.

From the 1960s to the 1980s, the IWW had various small organizing drives. Membership included a number of cooperatively owned and collectively run enterprises especially in the printing industry: Red & Black (Detroit), Lakeside (Madison, Wisconsin), and Harbinger (Columbia, South Carolina). The University Cellar, a non-profit campus bookstore formed by University of Michigan students, was for several years the largest organized IWW shop with about 100 workers. In the 1960s, Rebel Worker was published in Chicago by the surrealists Franklin and Penelope Rosemont. One edition was published in London with Charles Radcliffe who went on to become involved with the Situationist International. By the 1980s, the "Rebel Worker" was being published as an official organ again, from the IWW's headquarters in Chicago, and the New York area was publishing a newsletter as well; a record album of Wobbly music, "Rebel Voices," was also released.

In the 1990s, the IWW was involved in many labor struggles and free speech fights, including Redwood Summer, and the picketing of the Neptune Jade in the port of Oakland in late 1997.

IWW organizing drives in recent years have included a major campaign to organize Borders Books in 1996, a strike at the Lincoln Park Mini Mall in Seattle that same year, organizing drives at Wherehouse Music, Keystone Job Corps, the community organization ACORN, various homeless and youth centers in Portland, Oregon, sex industry workers, and recycling shops in Berkeley, California. IWW members have been active in the building trades, marine transport, ship yards, high tech industries, hotels and restaurants, public interest organizations, schools and universities, recycling centers, railroads, bike messengers, and lumber yards.

The IWW has stepped in several times to help the rank and file in mainstream unions, including saw mill workers in Fort Bragg in California in 1989, concession stand workers in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1990s, and most recently at shipyards along the Mississippi River.

In the early 2000s the IWW organized Stonemountain and Daughter Fabrics, a fabric/seamstress shop in Berkeley. The shop has remained under contract with the IWW to this day.

In 2004, an IWW union was organized in a New York City Starbucks. And in 2006, the IWW continued efforts at Starbucks by organizing several Chicago area shops.[11] In September of 2004, IWW-organized short haul truck drivers in Stockton, California walked off their jobs and went on a strike. Nearly all demands were met. Despite early victories in Stockton, the truck drivers union ceased to exist in mid-2005. In Chicago the IWW began an effort to organize bicycle messengers with some success. Between 2003 and 2006, the IWW organized unions at food co-operatives in Seattle, Washington and Pittsburgh, PA. The IWW represents administrative and maintenance workers under contract in Seattle, while the union in Pittsburgh lost 22-21 in an NLRB election, only to have the results invalidated in late 2006, based on management's behavior before the election. Recent activity includes a sizeable industrial campaign among immigrant foodstuffs workers in New York City, and building a presence in Los Angeles by organizing short-haul truckers and taxi drivers.

The city of Berkeley's recycling is picked up, sorted, processed, and sent out all through two different IWW organized enterprises.

Besides IWW's traditional practice of organizing industrially, the Union has been open to new methods such as organizing geographically, for instance, seeking to organize retail workers in a certain business district, as in Philadelphia.

The union has also participated in such worker-related issues as protesting involvement in the war in Iraq, opposing sweatshops and supporting a boycott of Coca Cola for that company's alleged support of the suppression of workers rights in Colombia.

In 2006, the IWW moved its headquarters to Cincinnati, Ohio.

Also in 2006, the IWW Bay Area Branch organized the Landmark Shattuck Cinemas. The Union has been negotiating for a contract and hopes to gain one through workplace democracy and organizing directly and taking action when necessary.

Current membership is about 2000 (about 900 in good standing), with most members in the United States, but many also located in Australia, Canada, Ireland, and the United Kingdom.

The IWW outside the U.S.

The IWW in Australia

Australia encountered the IWW tradition early. In part this was due to the local De Leonist SLP following the industrial turn of the US SLP. The SLP formed an IWW Club in Sydney in October 1907. Members of other socialist groups also joined it, and the special relationship with the SLP soon proved to be a problem. The 1908 split between the Chicago and Detroit factions in the United States was echoed by internal unrest in the Australian IWW from late 1908, resulting in the formation of a pro-Chicago local in Adelaide in May 1911 and another in Sydney six months later. By mid 1913 the "Chicago" IWW was flourishing and the SLP-associated pro-Detroit IWW Club in decline.[12] In 1916, the "Detroit" IWW in Australia followed the lead of the U.S. body and renamed itself the Workers' International Industrial Union.[13]

The early Australian IWW used a number of tactics from the US, including free speech fights. However there early appeared significant differences of practice between the Australian IWW and its US parent; the Australian IWW tended to co-operate where possible with existing unions rather than forming its own, and in contrast with the US body took an extremely open and forthright stand against involvement in World War I. The IWW cooperated with many other unions, encouraging industrial unionism and militancy. In particular, the IWW's strategies had a large effect on the Australasian Meat Industry Employees Union. The AMIEU established closed shops and workers councils and effectively regulated management behavior towards the end of the 1910s.

The IWW was well known for opposing the First World War from 1914 onwards, and in many ways was at the front of the anti-conscription fight. A narrow majority Australians voted against conscription in a very bitter hard-fought referendum in October 1916, and then again in December 1917, Australia being the only belligerent in World War One without conscription. In very significant part this was due to the agitation of the IWW, a group which probably never had as many as 500 members in Australia at its peak. The IWW founded the Anti-Conscription League (ACL) in which IWW members worked with the broader labor and peace movement, and also carried on an aggressive propaganda campaign in its own name; leading to the imprisonment of Tom Barker (1887-1970) the editor of the IWW paper Direct Action, sentenced to twelve months in March 1916. A series of arson attacks on commercial properties in Sydney was widely attributed to the IWW campaign to have Tom Barker released. He was indeed released in August 1916, but twelve mostly prominent IWW activists, the so-called Sydney Twelve were arrested in NSW in September 1916 for arson and other offences. (Their trial and eventual imprisonment would become a cause celebre of the Australian labor movement on the basis that there was no convincing evidence that any of them had been involved in the arson attacks.) A number of other scandals were associated with the IWW, a five pound note forgery scandal, the so-called Tottenham tragedy in which the murder of a police officer was blamed on the IWW, and above all the IWW was blamed for the defeat of the October 1916 conscription referendum. In December 1916 the Commonwealth government lead by Labour Party renegade Billy Hughes declared the IWW an illegal organization under the Unlawful Associations Act. Eighty six IWW members immediately defied the law and were sentenced to six months imprisonment, this was certainly a high percentage of the Australian IWW's active membership but it is not known how high. Direct Action was suppressed, its circulation was at its peak of something over 12,000.[14] During the war over 100 IWW members Australia-wide were sentenced to imprisonment on political charges,[15] including the veteran activist and icon of the labor, socialist and anarchist movements Monty Miller.

The IWW continued illegally operating with the aim of freeing its class war prisoners and briefly fused with two other radical tendencies—from the old Socialist parties and Trades Halls—to form a larval communist party at the suggestion of the militant revolutionist and Council Communist Adela Pankhurst. The IWW however left the CPA shortly after its formation, taking with it the bulk of militant industrial worker members.

By the 1930s, the IWW in Australia had declined significantly, and took part in unemployed workers movements which were led largely by the now Stalinized CPA. The poet Harry Hooton became involved with it around this time. In 1939, the Australian IWW had four members, according to surveillance by government authorities, and these members were consistently opposed to the second world war. After the Second World War the IWW would become one of the influences on the Sydney Libertarians who were in turn a significant cultural and political influence.

Today, the IWW still exists in Australia, in larger numbers than the 1940s, but due to the nature of the Australian industrial relations system, it is unlikely to win union representation in any workplaces in the immediate future. More significant is its continuing place in the mythology of the militant end of the Australian labor movement.[16] One example of the integration of ex-IWW militants into the mainstream labor movement is the career of Donald Grant, one of the Sydney Twelve sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment for conspiracy to commit arson and other crimes. Released unbowed from prison in August 1920, he would soon break with the IWW over its anti-political stand, standing for the NSW Parliament for the Industrial Socialist Labour Party unsuccessfully in 1922 and then in 1925 for the mainstream Australian Labor Party (ALP) also unsuccessfully. But this reconciliation with the ALP and the electoral system did not prevent him being imprisoned again in 1927 for street demonstrations supporting Sacco and Vanzetti. He would eventually represent the ALP in the NSW Legislative Council in 1931-1940 and the Australian Senate 1943-1956 [17] No other member of the Australian IWW actually entered Parliament but Grants career is emblematic in the sense that the ex-IWW militants by and large remained in the broader labour movement, bringing some greater or lesser part of their heritage with them.

"Bump Me Into Parliament" is the most notable Australian IWW song, and is still current. It was written by ship's fireman William "Bill" Casey, later Secretary of the Seaman's Union in Queensland.[18]

The IWW in the UK

Syndicalists and radical unionists, such as James Connolly in the UK and Ireland have remained close to the IWW in the U.S. Although much smaller than their North American counterparts, the BIROC (British Isles Regional Organising Committee) reported in 2006 that there were nearly 200 members in the UK and Ireland. Numbers have been steadily increasing since the 1990s, and in the year 2005-2006 numbers leapt up by around 25 percent.

Having been present in the UK in various guises since 1906, the IWW was present to varying extents in many of the struggles in the early decades of the twentieth century, including the UK General Strike of 1926 and the dockers' strike of 1947. More recently, IWW members were involved in the Liverpool dockers' strike that took place between 1995 and 1998, and numerous other events and struggles throughout the 1990s and 2000s, including the successful unionizing of several workplaces, including support workers for the Scottish Socialist Party. In 2005, the IWW's centenary year, a stone was laid in a forest in Wales, commemorating the centenary, as well as the death of U.S. IWW and Earth First! activist Judi Bari.

The IWW has launched a Website and has eight general branches and several organizing groups around the UK alongside two budding industrial networks for health workers and education workers and a job branch for support workers at the Scottish Parliament. The IWW publishes a magazine aimed at the British and Irish members, Bread and Roses, and an industrial newsletter for health workers.

The IWW in Canada

The IWW was active in Canada from a very early point in the organization's history, especially in Western Canada, primarily in British Columbia. The union was active in organizing large swaths of the lumber and mining industry along the coast of BC, and Vancouver Island. At times the union was perhaps better known in certain circles under their organizing motto rather than the name of the union itself, that being the "One Big Union." The Wobblies also had relatively close links with the Socialist Party of Canada.[19]

Arthur "Slim" Evans, organizer in the Relief Camp Workers' Union and the On-to-Ottawa Trek was a wobbly.

Today the IWW remains active in the country with numerous branches active in Vancouver, Edmonton, Winnipeg, Ottawa, and Toronto. The largest branch is currently in Edmonton.

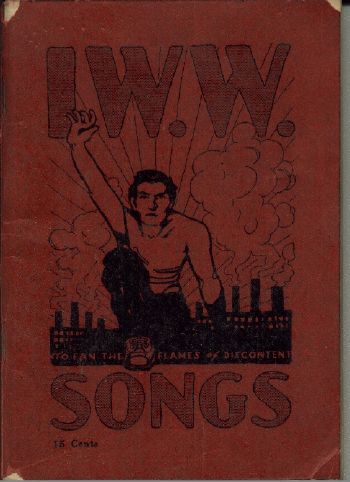

Folk music and protest songs

One feature of IWW followers from their inception is song. To counteract management sending in the Salvation Army band to cover up the Wobbly speakers, Joe Hill wrote parodies of Christian hymns so that union members could sing along with the Salvation Army band, but with their own purposes (for example, "In the Sweet By and By" became "There'll Be Pie in the Sky When You Die (That's a Lie)"). From that start in exigency, Wobbly song writing became legendary. The IWW collected its official songs in the Little Red Songbook and continues to update this book to the present time. In the 1960s, the American folk music revival in the United States brought a renewed interest in the songs of Joe Hill and other Wobblies, and seminal folk revival figures such as Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie had a pro-Wobbly tone, while some were members of the IWW. Among the protest songs in the book are "Hallelujah, I'm a Bum" (This song was never popular among members, and removed after appearing in only the first edition), "Union Maid," and "I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night." Perhaps the best known IWW song is "Solidarity Forever." The songs have been performed by dozens of artists, and Utah Phillips has performed the songs in concert and on recordings for decades. Other prominent I.W.W. song writers include Ralph Chaplin who authored "Solidarity Forever," and Leslie Fish.

The Finnish I.W.W. community produced several folk singers, poets and song writers, the most famous being Matti Valentine Huhta (better known as T-Bone Slim), who penned "The Popular Wobbly" and "The Mysteries of a Hobo's Life." Hiski Salomaa, whose songs were composed entirely in Finnish (and Finglish), remains a widely recognized early folk musician in his native Finland as well as in sections of the Midwest United States, Northern Ontario, and other areas of North America with high concentrations of Finns. Salomaa, who was a tailor by trade, has been referred to as the Finnish Woody Guthrie. Arthur Kylander, who worked as a lumberjack, is a lesser known, but important Finnish I.W.W. folk musician. Kylander's lyrics range from the difficulties of the immigrant laborer's experience to more humorous themes. Arguably, the wanderer, a recurring theme in Finnish folklore dating back to pre-Christian oral tradition (as with Lemminkäinen in the Kalevala), translated quite easily to the music of Huhta, Salomaa, and Kylander; all of whom have songs about the trials and tribulations of the hobo.

IWW lingo

The origin of the name "Wobbly" is uncertain. Many believe it refers to a tool known as a "wobble saw." One often repeated anecdote suggests that a Chinese restaurant owner in Vancouver would extend credit to IWW members and, unable to pronounce the "W," would ask if they were a member of the "I Wobble Wobble,"[20][21] although this is likely apochryphal.

Notable members

Notable members of the Industrial Workers of the World have included Lucy Parsons, Helen Keller,[22] Joe Hill, Ralph Chaplin, Ricardo Flores Magon, James P. Cannon, James Connolly, Jim Larkin, Paul Mattick, Big Bill Haywood, Eugene Debs, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, Sam Dolgoff, Monty Miller, Indian Nationalist Lala Hardayal, Frank Little, ACLU founder Roger Nash Baldwin, Harry Bridges, Buddhist beat poet Gary Snyder, Australian poets Harry Hooton and Lesbia Harford, anthropologist David Graeber, graphic artist Carlos Cortez, counterculture icon Kenneth Rexroth, Surrealist Franklin Rosemont, Rosie Kane and Carolyn Leckie, former Members of the Scottish Parliament, Judi Bari, folk musicians Utah Phillips and David Rovics, mixed martial arts fighter Jeff Monson, Finnish folk music legend Hiski Salomaa, U.S. Green Party politician James M. Branum, Catholic Workers Dorothy Day and Ammon Hennacy, and nuclear engineer Susanna Johnson. The former lieutenant governor of Colorado, David C. Coates was a labor militant, and was present at the founding convention,[23] although it is unknown if he became a member. It has long been rumored, but not yet proven, that baseball legend Honus Wagner was also a Wobbly. Senator Joe McCarthy accused journalist Edward R. Murrow of having been an IWW member. The organization's most famous current member is Noam Chomsky.

See also

- General strike

- Socialism

Notes

- ↑ IWW, Preamble & Constitution of the Industrial Workers of the World. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Genealogia, Finnish-American Workmen's Associations Auvo Kostiainen.

- ↑ NEIU, Short history of Pressed Steel Car Company. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ History Link, Spokane—Thumbnail History at SpokaneHistory.org. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ One Big Union, 1986.

- ↑ ODMP, Deputy Sheriff Jefferson F. Beard.at the Officer Down Memorial Page.

- ↑ ODMP, Deputy Sheriff Charles O. Curtiss.

- ↑ Peter Carlson, Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood (1983), 241.

- ↑ Peter Carlson, Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood (1983), 242-244.

- ↑ Find a Grave, Wesley Everest. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Philip Dawdy, A Union Shop on Every Block, Seattle Weekly. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Turner, Industrial Labour and Politics: The Dynamics of the Labour Movement in Eastern Australia 1900-1921 (Canberra: Australian National University Press, 1965).

- ↑ Turner, 150.

- ↑ Turner.

- ↑ Bobbie Oliver, War and Peace in Western Australia: The Social and Political Impact of the Great War 1914-1926 (University of Western Australia Press, 1995, ISBN 1-875560-57-2), 81.

- ↑ Workers' Online, "Flowers For the Rebels Faded." Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Australian National Dictionary of Biography Grant, Donald McLennan (1888 - 1970). Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Turner.

- ↑ Social History, Canadian Socialist History Project. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Mark Leier, Where the Fraser River Flows: The Industrial Workers of the World in British Columbia (Vancouver: New Star Books, 1990).

- ↑ Stewart Bird and Deborah Shaffer (directors), The Wobblies (1979).

- ↑ Marxists.org, Helen Keller. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Peter Carlson, Roughneck: The Life and Times of Big Bill Haywood, 78.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brissenden, Paul F. 1919. The IWW: A Study of American Syndicalism, 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press. OCLC 39558534.

- Buhle, Paul, and Nicole Schulman (eds.). Wobblies: A Graphic History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Verso. ISBN 1-84467-525-4.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn. 2000. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-06905-6.

- Flank, Lenny. 2007. IWW: A Documentary History. St Petersburg, FL: Red and Black Publishers. ISBN 979-0-9781813-5-1.

- Green, Archie, and David Roediger, Franklin Rosemont, and Salvatore Salerno (eds.). 2007. The Big Red Songbook. Charles H. Kerr. ISBN 0-88286-277-4.

- Kornbluh, Joyce L. (ed.). Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-88286-237-5.

- Marxists Internet Archive. Documents, Essays and Analysis for a History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Retrieved April 16, 2005.

- McClelland, John, Jr. 1987. Wobbly War: The Centralia Story. (Washington State Historical Society. ISBN 0-917048-62-8.

- Moran, William. 2002. Belles of New England: The Women of the Textile Mills and the Families Whose Wealth They Wove. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30183-9.

- Rosemont, Franklin, and Charles Radcliffe. 2005. Dancin' in the Streets: Anarchists, IWWs, Surrealists, Situationists and Provos in the 1960s as Recorded in the Pages of Rebel Worker and Heatwave. Charles H. Kerr. ISBN 0-88286-301-0.

- Rosen, Ellen Doree. 2004. A Wobbly Life: IWW Organizer E. F. Doree. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3203-X.

- Thompson, Fred. 1955. The I. W. W.: Its First Fifty Years. Chicago: IWW. OCLC 2907835.

- Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs. Industrial Workers of the World Collection. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Official Web sites: Global Headquarters—British Isles

- Paul Buhle, "The Legacy of the IWW," Monthly Review.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.