Darjeeling

|   Darjeeling West Bengal â¢Â India | |

| Coordinates: | |

| Time zone | IST (UTC+5:30) |

| Area ⢠Elevation |

10.57 km² (4 sq mi) ⢠2,050 m (6,726 ft)[1] |

| District(s) | Darjeeling |

| Population ⢠Density |

132,016 (2011) ⢠12,490 /km² (32,349 /sq mi) |

| Parliamentary constituency | Darjeeling |

| Assembly constituency | Darjeeling |

| Codes ⢠Pincode ⢠Telephone ⢠Vehicle |

⢠734101 ⢠+0354 ⢠WB-76 WB-77 |

Coordinates:

Darjeeling (Nepali: दारà¥à¤à¥à¤²à¤¿à¤à¥à¤, Bengali: দারà§à¦à¦¿à¦²à¦¿à¦) refers to a town in the Indian state of West Bengal, the headquarters of Darjeeling district. Situated in the Shiwalik Hills on the lower range of the Himalaya, the town sits at an average elevation of 2,134 m (6,982 ft). The name "Darjeeling" comes from a combination of the Tibetan words Dorje ("thunderbolt") and ling ("place"), translating to "the land of the thunderbolt." During the British Raj in India, Darjeeling's temperate climate led to its development as a hill station (hill town) for British residents to escape the heat of the plains during the summers.

Darjeeling has become internationally famous for its tea industry and the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The tea plantations date back to the mid nineteenth century as part of a British development of the area. The tea growers of the area developed distinctive hybrids of black tea and fermenting techniques, with many blends considered among the world's finest. UNESCO declared the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway, connecting the town with the plains, a World Heritage Site in 1999 and constitutes one of the few steam engines still in service in India.

Darjeeling has several British-style public schools, which attract students from many parts of India and neighboring countries. The town, along with neighboring Kalimpong, developed into a major center for the demand of a separate Gorkhaland state in the 1980s, though the separatist movement has gradually decreased over the past decade due to the setting up of an autonomous hill council. In the recent years the town's fragile ecology has been threatened by a rising demand for environmental resources, stemming from growing tourist traffic and poorly planned urbanization.

History

The history of Darjeeling has intertwined with the histories of Nepal, Bhutan, Sikkim, and Bengal. The kingdoms of Nepal and Sikkim ruled intermittently the area around Darjeeling until the early nineteenth century,[2] with settlement consisting of a few villages of Lepcha woodspeople. In 1828, a delegation of British East India Company officials on their way to Sikkim stayed in Darjeeling, deeming the region a suitable site for a sanitarium for British soldiers.[3] The Company negotiated a lease of the area from the Chogyal of Sikkim in 1835.[2] Arthur Campbell, a surgeon with the Company and Lieutenant Napier (later Lord Napier of Magdala) received the responsibility to found a hill station there.

The British established experimental tea plantations in Darjeeling in 1841. The success of those experiments led to the development of tea estates all around the town in the second half of the nineteenth century.[4]

The British Indian Empire annexed Darjeeling a few years after an incident of discord between Sikkim and the British East India Company in 1849. During that time immigrants, mainly from Nepal, arrived to work at construction sites, tea gardens, and on other agriculture-related projects.[3] Scottish missionaries undertook the construction of schools and welfare centers for the British residents, laying the foundation for Darjeeling's high reputation as a center of education. The opening of the Darjeeling Himalayan Railway in 1881 hastened the development of the region.[5] In 1898, a major earthquake rocked Darjeeling (known as the "Darjeeling disaster") causing severe damage to the town and the native population.[6]

The British initially decreed the Darjeeling area a "Non-Regulation District" (a scheme of administration applicable to economically less advanced districts in the British Raj[7])âacts and regulations of the British Raj needed special consideration before applying to the district in line with rest of the country. The British ruling class constituted Darjeeling's elite residents of the time, who visited Darjeeling every summer. An increasing number of well-to-do Indian residents of Kolkata (then Calcutta), affluent Maharajas of princely states and land-owning zamindars also began visiting Darjeeling.[8] The town continued to grow as a tourist destination, becoming known as the "Queen of the Hills."[9] The town saw little significant political activity during the freedom struggle of India owing to its remote location and small population. Revolutionaries failed in an assassination attempt on Sir John Anderson, the Governor of Bengal in the 1930s.

After the independence of India in 1947, Darjeeling merged with the state of West Bengal. The separate district of Darjeeling emerged as an established region consisting of the hill towns of Darjeeling, Kurseong, Kalimpong and some parts of the Terai region. When the People's Republic of China annexed Tibet in 1950, thousands of Tibetan refugees settled across Darjeeling district. A diverse ethnic population gave rise to socio-economic tensions, and the demand for the creation of the separate states of Gorkhaland and Kamtapur along ethnic lines grew popular in the 1980s. The issues came to a head after a 40-day strike called by the Gorkha National Liberation Front, during which violence gripped the city, causing the state government to call in the Indian Army to restore order. Political tensions largely declined with the establishment of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council under the chairmanship of Subash Gishing. The DGHC received semi-autonomous powers to govern the district. Later its name changed to "Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council" (DGAHC). Although peaceful now, the issue of a separate state still lingers in Darjeeling.

Geography

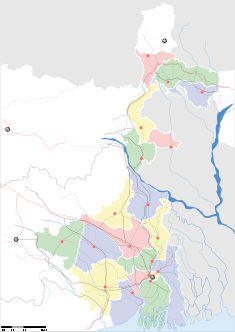

Darjeeling stands at an average elevation of 2,050 m or 6,725 ft in the Darjeeling Himalayan hill region on the Darjeeling-Jalapahar range that originates in the south from Ghum.[10] The range has a Y shape with the base resting at Katapahar and Jalapahar and two arms diverging north of Observatory Hill. The north-eastern arm dips suddenly and ends in the Lebong spur, while the north-western arm passes through North Point and ends in the valley near Tukver Tea Estate.[2]

Darjeeling serves as the main town of the Sadar subdivision and also the headquarters of the district. Most of the district, including the town of Darjeeling lies in the Shiwalik Hills (or Lower Himalaya). Sandstone and conglomerate formations chiefly make up the soil composition, the solidified and upheaved detritus of the great range of Himalaya. The soil, often consolidating poorly (the permeable sediments of the region fail to retain water between rains), has proven unsuitable for agriculture. The area has steep slopes and loose topsoil, leading to frequent landslides during the monsoons. According to the Bureau of Indian Standards, the town falls under seismic zone-IV, (on a scale of I to V, in order of increasing proneness to earthquakes) near the convergent boundary of the Indian and the Eurasian tectonic plates, subject to frequent quakes. The hills nestle within higher peaks and the snow-clad Himalayan ranges tower over the town in the distance. Mount Kanchenjunga (8,591 m or 28,185 ft)âthe world's third-highest peakârepresents the most prominent peak visible. In days clear of clouds, Nepal's Mount Everest (8,848Â meters (29,029Â ft)) stands majestically in view.

Several tea plantations operate in the area. The town of Darjeeling and surrounding region face deforestation due to increasing demand for wood fuel and timber, as well as air pollution from increasing vehicular traffic.[11] Flora around Darjeeling includes temperate, deciduous forests of poplar, birch, oak, and elm as well as evergreen, coniferous trees of wet alpine. Dense evergreen forests lie around the town, where a wide variety of rare orchids grow. Lloyd's Botanical Garden preserves common and rare species of flora, while the Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park represents the only specialized zoo in the country conserving and breeding endangered Himalayan species.[12]

Climate

Darjeeling's temperate climate has five distinct seasons: spring, summer, autumn, winter, and the monsoons. Summers (lasting from May to June) have mild temperatures, rarely crossing 25 °C (77 °F). Intense torrential rains characterize the monsoon season from June to September, often causing landslides that block Darjeeling's land access to the rest of the country. In winter temperature averages 5â7 °C (41â44 °F). Occasionally the temperatures drop below freezing; snow rarely falls. During the monsoon and winter seasons, mist and fog often shroud Darjeeling. The annual mean temperature measures 12 °C (53 °F); monthly mean temperatures range from 5â17 °C (41â62 °F). 26.7 °C (80.1 °F) on 23 August 1957 marked the highest temperature ever recorded in the district; the lowest-ever temperature recorded fell to -6.7°C (20 °F).[13] The average annual precipitation totals 281.8 cm (110.9 in), with the highest incidence occurring in July (75.3 cm or 29.6 in).

Civic administration

The Darjeeling urban agglomeration consists of Darjeeling Municipality and the Pattabong Tea Garden. Established in 1850, the Darjeeling municipality maintains the civic administration of the town, covering an area of 10.57 km² (4.08 mi²). The municipality consists of a board of councillors elected from each of the 32 wards of Darjeeling town as well as a few members nominated by the state government. The board of councillors elects a chairman from among its elected members; the chairman serves as the executive head of the municipality. The Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF) at present holds power in the municipality. The Gorkha-dominated hill areas of the whole Darjeeling district falls under the jurisdiction of the Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council since its formation in 1988. The DGHC's elected councillors have the authorization to manage certain affairs of the hills, including education, health and tourism. The town lay within the Darjeeling Lok Sabha constituency and elects one member to the Lok Sabha (Lower House) of the Indian Parliament. It elects one member in the West Bengal state legislative assembly, the Vidhan Sabha. The Indian National Congress won the parliamentary election in 2004, while GNLF won the state assembly seat in the 2006 polls. Darjeeling town comes under the jurisdiction of the district police (a part of the state police); a Deputy Superintendent of Police oversees the town's security and law affairs. Darjeeling municipality area has two police stations at Darjeeling and Jorebungalow.

Utility services

Natural springs provide most of Darjeeling's water supplyâcollected water routes to Senchal Lake (10 km or 6.2 miles southeast of town), then flows by pipe to the town. During the dry season, when spring-supplied water proves insufficient, the city pumps water from Khong Khola, a nearby small perennial stream. A steadily widening gap between water supply and demand has been growing; just over 50 percent of the town's households connect to the municipal water supply system.[2] The town has an underground sewage system that collects domestic waste from residences and about 50 community toilets. Waste then conveys by pipes to six central septic tanks, ultimately disposed in natural jhoras (waterways); roadside drains also collect sewage and storm water. Municipal Darjeeling produces about 50 tonnes (110,200 lb) of solid waste every day, disposing of in nearby disposal sites.[2]

The West Bengal State Electricity Board supplies electricity, and the West Bengal Fire Service provides emergency services for the town. The town often suffers from power outages while the electrical supply voltage has proven unstable, making voltage stabilisers popular with many households. Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council maintain almost all of the primary schools. The total length of all types of roadsâincluding stepped paths within the municipalityâmeasures around 90 km (56 miles); the municipality maintains them.[2]

Economy

Tourism and the tea industry constitute the two most significant contributors to Darjeeling's economy. Many consider Darjeeling tea, widely popular, especially in the UK and the countries making up the former British Empire, the best of black teas. The tea industry has faced competition in recent years from tea produced in other parts of India as well as other countries like Nepal.[14] Widespread concerns about labor disputes, worker layoffs and closing of estates have affected investment and production.[15] A workers' cooperative model has been used on several tea estates, while developers have been planning to convert others into tourist resorts.[15] Women make up more than 60 per cent of workers in the tea gardens. Workers normally receive compensation half in cash and half in other benefits like accommodation, subsidized rations, free medical benefits etc.[16]

The district's forests and other natural wealth have been adversely affected by an ever-growing population. The years since independence have seen substantial advances in the area's education, communication and agricultureâthe latter including the production of diverse cash crops like potato, cardamom, ginger, and oranges. Farming on terraced slopes has proven a major source of livelihood for the rural populace around the town and it supplies the town with fruits and vegetables.

Tourists enjoy the summer and spring seasons most, keeping many of Darjeeling's residents employed directly and indirectly, with many residents owning and working in hotels and restaurants. Many people earn a living working for tourism companies and as guides. Darjeeling has become a popular filming destination for Bollywood and Bengali cinema; films such as Aradhana, Main Hoon Na, Kanchenjungha have been filmed there. As the district headquarters, Darjeeling employs many in government offices. Small contributions to the economy come from the sale of traditional arts and crafts of Sikkim and Tibet.

Transport

The town of Darjeeling can be reached by the 80 km (50 miles) long Darjeeling Himalayan Railway (nicknamed the "Toy Train") from Siliguri, or by the Hill Cart Road (National Highway 55) that follows the railway line. The Darjeeling Himalayan Railway uses 60 cm (2 ft) narrow-gauge rails. UNESCO declared the railroad a World Heritage Site in 1999, making it only the second railway in the world to receive that honor.[5] Regular bus services and hired vehicles connect Darjeeling with Siliguri and the neighboring towns of Kurseong, Kalimpong and Gangtok. Four wheel drives, including Land Rovers, prove the most popular means of transport, as they can easily navigate the steep slopes in the region. Landslides often disrupt road and rail communications during monsoons due. Bagdogra near Siliguri, located about 93 km (58 miles) from Darjeeling constitutes the nearest airport. Indian Airlines, Jet Airways and Air Deccan represent the three major carriers that connect the area to Delhi, Kolkata and Guwahati. The railway station in New Jalpaiguri constitutes the closest connection with almost all major cities of the country. Within the town, people usually get around by walking. Residents also use bicycle, two-wheelers and hired taxis for traveling short distances. The Darjeeling Ropeway, functional from 1968 to 2003, was closed for eight years after an accident killed four tourists.[17] The ropeway (cable car) goes up to Tukvar, returning to Singamari base station at Darjeeling.[18]

Demographics

According to the 2011 census of India, Darjeeling urban agglomeration has a population of 132,016, out of which 65,839 were males and 66,177 were females. The sex ratio is 1,005 females per 1,000 males. The 0â6 years population is 7,382. Effective literacy rate for the population older than 6 years is 93.17 per cent.[19]

The women make a significant contribution as earning members of households and the workforce. The town houses approximately 31 percent of its population in the slums and shanty buildingsâa consequence of heavy immigration.[2] Hinduism constitutes the major religion, followed by Buddhism. Christians and Muslims form sizable minorities. The population's ethnic composition closely links with Bhutan, Nepal, Sikkim and Bengal. The majority of the populace has ethnic Nepali background, having migrated to Darjeeling in search of jobs during the British rule. Indigenous ethnic groups include the Lepchas, Bhutias, Sherpas, Rais, Yamloos, Damais, Kamais, Newars and Limbus. Other communities that inhabit Darjeeling include the Bengalis, Marwaris, Anglo-Indians, Chinese, Biharis and Tibetans. Nepali (Gorkhali) represents the most commonly spoken language; people also use Hindi, Bengali and English.

Darjeeling has seen significant growth in its population during the last century, especially since the 1970s. Annual growth rates reached as high as 45 percent in the 1990s, far above the national, state, and district averages.[2] The colonial town had been designed for a mere population of 10,000, and subsequent growth has created extensive infrastructural and environmental problems. In geological terms, the region has formed relatively recently; unstable in nature, the region suffers from a host of environmental problems.[2] Environmental degradation, including denudation of the surrounding hills has adversely affected Darjeeling's appeal as a tourist destination.[11]

Culture

Apart from the major religious festivals of Diwali, Christmas, Dussera, and Holi, the diverse ethnic populace of the town celebrates several local festivals. The Lepchas and Bhutias celebrate new year in January, while Tibetans celebrate the new year (Losar) with "Devil Dance" in FebruaryâMarch. The Maghe sankranti, Ram Navami, Chotrul Duchen, Buddha Jayanti, the birthday of the Dalai Lama and Tendong Lho Rumfaat represent some other festivals, some distinct to local culture and others shared with the rest of India, Nepal, Bhutan and Tibet. Darjeeling Carnival, initiated by a civil society movement known as The Darjeeling Initiative, lasts for ten days every year, held during the winter. The carnival quickly became famous for its high quality portrayal of the rich musical and cultural heritage of Darjeeling Hills.

The momo, a steamed dumpling containing pork, beef and vegetables cooked in a doughy wrapping and served with watery soup represents a popular food in Darjeeling. Wai-Wai, a favorite with people, comes as a packaged snack consisting of noodles eaten either dry or in soup form. In Darjeeling, people frequently eat, and sometimes chew, Churpee, a kind of hard cheese made from cow's or yak's milk. A form of noodle called thukpa, served in soup form represents another food popular in Darjeeling. A large number of restaurants offer a wide variety of traditional Indian, continental and Chinese cuisines to cater to the tourists. Tea, procured from the famed Darjeeling tea gardens, as well as coffee, constitute the most popular beverages. Chhang designates a local beer made from millet.

Colonial architecture characterizes many buildings in Darjeeling; several mock Tudor residences, Gothic churches, the Raj Bhawan (Governor House), Planters' Club and various educational institutions provide examples. Buddhist monasteries showcase the pagoda style architecture. Darjeeling has established itself as a center of music and a niche for musicians and music admirers. Singing and playing musical instruments represents a common pastime among the resident population, who take pride in the traditions and role of music in cultural life.[20] Western music has become popular among the younger generation while Darjeeling also constitutes a major center of Nepali rock music. Cricket and football stand as the most popular sports in Darjeeling. Locals improvised form of ball made of rubber garters (called chungi) for playing in the steep streets.

Some notable places to visit include the Tiger Hill, the zoo, monasteries and the tea gardens. The town attracts trekkers and sportsmen seeking to explore the Himalayas, serving as the starting point for climbing attempts on some Indian and Nepali peaks. Tenzing Norgay, one of the two men to first climb Mount Everest, spent most of his adult life in the Sherpa community in Darjeeling. His success provided the impetus to establish the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute in Darjeeling in 1954. In the Tibetan Refugee Self Help Center, Tibetans display their crafts like carpets, wood and leather work. Several monasteries like Ghum Monastery (8 km or 5 miles from the town), Bhutia Busty monastery, Mag-Dhog Yolmowa preserve ancient Buddhist scripts.

Education

The state government, private, and religious organizations, run Darjeeling's schools. They mainly use English and Nepali as their medium of instruction, although also stressing the national language Hindi and the official state language Bengali. The schools affiliate either with the ICSE, the CBSE, or the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education. Having been a summer retreat for the British in India, Darjeeling soon became the place of choice for the establishment of public schools on the model of Eton, Harrow and Rugby, allowing the children of British officials to obtain an exclusive education.[21] Institutions such as St. Joseph's College (School Dept.), Loreto Convent, St. Paul's School and Mount Hermon School attract students from all over India and South Asia. Many schools (some more than a hundred years old) still adhere to the traditions from its British and colonial heritage. Darjeeling hosts three collegesâSt. Joseph's College, Loreto College and Darjeeling Government Collegeâall affiliated to University of North Bengal in Siliguri.

Media

Newspapers in Darjeeling include English language dailies, The Statesman and The Telegraph, printed in Siliguri, and The Hindustan Times and the Times of India printed in Kolkata; they arrive after a day's delay. In addition to those one can also find Nepali, Hindi and Bengali publications. Nepali newspapers include "Sunchari," "Himali Darpan". The public radio station, All India Radio alone has reception in Darjeeling. Darjeeling receives almost all the television channels that broadcast throughout the nation. Apart from the state-owned terrestrial network Doordarshan, cable television serves most of the homes in the town, while satellite television commonly serves the outlying areas and in wealthier households. Besides mainstream Indian channels, the town also receives local Nepali language channels. Internet cafés abound in the main market area, served through dial-up access. BSNL provides a limited form of broadband connectivity of up to 128 kbit/s with DIAS (Direct Internet Access System) connections. Local cellular companies such as BSNL, Reliance Infocomm, Hutch and Airtel service the area.

Notes

- â District Profile Darjeeling district.

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Vimal Khawas, Urban Management in Darjeeling Himalaya - A Case Study of Darjeeling Municipality 2003. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â 3.0 3.1 History of Darjeeling. Darjeeling Government website. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Niraj Lama, History of Darjeeling tea Happy Earth Tea Company, May 17, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â 5.0 5.1 Mountain Railways of India UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Bob Hopkins, Patrick Mackay, A Pride of Panners (Prestoungrange University Press, 2004), 43. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Sanjoy Borbara, Experiences on Autonomy in East and North East: A Report on the Third Civil Society Dialogue on Human Rights and Peace (Kolkata: Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group, 2003). Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â T.T. Shringla, Toy Train to Darjeeling. India Travelogue, 2003. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Darjeeling â The queen of Hills Himalayan Tourism. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Top 10 Places To Visit In Darjeeling Trans India Travels. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â 11.0 11.1 Report of the Evaluation Study on Hill Area Development Programme in Assam and West Bengal, Programme Evaluation Organisation Planning Commission Government of India New Delhi-110001, July 2010. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Padmaja Naidu Himalayan Zoological Park Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Temperature in Darjeeling, Gangtok, Kalimpong. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Darjeeling tea growers at risk BBC News, July 27, 2001. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â 15.0 15.1 Daniel B. Haber, Economy-India: Famed Darjeeling Tea Growers Eye Tourism for Survival. Inter Press Service News Agency, January 13, 2004. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Tarit Kumar Datta, V. Darjeeling tea, India Indian Institute of Management Calcutta. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Darjeeling ropeway reopens after more than 8 yrs Hindustani Times, February 2, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Darjeeling Ropeway: Rangeet Valley Passenger Cable Car. Darjeeling Tourism. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â Provisional Population Totals, Census of India 2011 Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- â D.S Rasaily and R.P. Lama, The Nature-centric Culture of the Nepalese. Retrieved May 3, 2018. In Baidyanath Saraswati (ed.), The Cultural Dimension of Ecology (New Delhi: Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, 1998).

- â Vinay Lal, "Hill Stations: Pinnacles of the Raj.". Review article on Dale Kennedy, The Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. The Book Review (Delhi) 17(9) (Sept. 1993):8-9. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bradnock, Robert, and Roma Bradnock. Footprint India Handbook, 13th ed. Footprint Handbooks, 2004. ISBN 1904777007

- Brown, Percy. Tours in Sikhim and the Darjeeling District. Calcutta: W. Newman & Co., 1934. ASIN B0008B2MIY

- Kennedy, Dane Keith. Magic Mountains: Hill Stations and the British Raj. University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520201884

- Lee, Ada. The Darjeeling Disaster: Triumph through Sorrow: The Triumph of the six Lee Children. Lee Memorial Mission, 1971.

- Ronaldshay, Earl of. Lands of the Thunderbolt: Sikhim, Chumbi and Bhutan. Reprint SLG Books; 3rd ed., 1993. ISBN 978-0961706661

- Saraswati, Baidyanath (ed.). Cultural Dimension of Ecology. India: DK Print World, Ltd., 1998. ISBN 812460102X

- Singh, S. Lonely Planet India, 11th ed., Lonely Planet Publications, 2005.

- Waddell, L. Austine. Among the Himalayas. Kessinger Publishing, 2004. ISBN 076618918X

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.