Mount Everest

| Mount Everest | |

|---|---|

Everest from Kala Patthar in Nepal | |

| Elevation | 29,029 feet (8,846 meters)[1] [Ranked 1st] |

| Location | Nepal and China (Tibet)[2] |

| Mountain range | Himalaya mountains |

| Prominence | 8,848 meters (29,029 feet) |

| Geographic coordinates | 27°59.17′N 86°55.31′E |

| First ascent | May 29, 1953, by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay |

| Easiest Climbing route | South Col (Nepal) |

Mount Everest—also known as Sagarmatha or Chomolungma—is the highest mountain on Earth, as measured by the height of its summit above sea level. The mountain, which is part of the Himalaya range in High Asia, is located on the border between Nepal and Tibet. Its summit was first reached in 1953 by Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Tenzing Norgay of Nepal. Its exact height is debated, but is approximately 29,000 feet above sea level. Climbing Everest has generated controversy in recent years as well over 200 people have died climbing the mountain.[3]

Challenging Everest

Several attempts to challenge Everest had failed before it was finally conquered in 1953.[4] The most famous of the previous challengers was the British adventurer George Mallory, who disappeared with his climbing partner Andrew Irvine, somewhere high on the northeast ridge during the first ascent of the mountain in June, 1924. The pair's last known sighting was only a few hundred meters from the summit. Mallory's ultimate fate was unknown for 75 years, until 1999 when his body was finally discovered.

In 1951, a British expedition led by Eric Shipton and including Edmund Hillary, traveled into Nepal to survey a new route via the southern face. Taking their cue from the British, in 1952 a Swiss expedition attempted to climb via the southern face, but the assault team of Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay turned back 600 feet short of the summit. The Swiss attempted another expedition in the autumn of 1952; this time a team including Lambert and Tenzing turned back at an earlier stage in the climb.

In 1953, a ninth British expedition, led by Baron of Llanfair Waterdine, John Hunt, returned to Nepal. Hunt selected two climbing pairs to attempt to reach the summit. The first pair turned back after becoming exhausted high on the mountain. The next day, the expedition made its second and final assault on the summit with its fittest and most determined climbing pair. The summit was eventually reached at 11:30 a.m. local time on May 29, 1953 by the New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa from Nepal, climbing the South Col Route. At the time, both acknowledged it as a team effort by the whole expedition, but Tenzing revealed a few years later that Hillary had put his foot on the summit first. They paused at the summit to take photographs and buried a few sweets and a small cross in the snow before descending. News of the expedition's success reached London on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation. Returning to Kathmandu a few days later, Hillary and Hunt discovered that they had been promptly knighted for their efforts.

Naming

The ancient Sanskrit names for the mountain are Devgiri for "Holy Mountain," and Devadurga. The Tibetan name is Chomolungma or Qomolangma, meaning "Mother of the Universe," and the related Chinese name is Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng or Shèngmǔ Fēng.

In 1865, the mountain was given its English name by Andrew Scott Waugh, the British surveyor-general of India. With both Nepal and Tibet closed to foreign travel, he wrote:

I was taught by my respected chief and predecessor, Colonel Sir [George] Everest to assign to every geographical object its true local or native appellation. But here is a mountain, most probably the highest in the world, without any local name that we can discover, whose native appellation, if it has any, will not very likely be ascertained before we are allowed to penetrate into Nepal. In the meantime the privilege as well as the duty devolves on me to assign…a name whereby it may be known among citizens and geographers and become a household word among civilized nations.

Waugh chose to name the mountain after Everest, first using the spelling "Mont Everest," and then "Mount Everest." However, the modern pronunciation of Everest is in fact different from Sir George's own pronunciation of his surname.

In the early 1960s, the Nepalese government realized that Mount Everest had no Nepalese name. This was because the mountain was not known and named in ethnic Nepal, that is, the Kathmandu valley and surrounding areas. The government set out to find a name for the mountain since the Sherpa/Tibetan name Chomolangma was not acceptable, as it would have been against the idea of unification, or Nepalization, of the country. The name Sagarmatha in Sanskrit for "Head of the Sky" was thus invented by Baburam Acharya.

In 2002, the Chinese People's Daily newspaper published an article making a case against the continued use of the English name for the mountain in the Western world, insisting that it should be referred to by its Tibetan name. The newspaper argued that the Chinese name preceded the English one, as Mount Qomolangma was marked on a Chinese map more than 280 years ago.

Measurement

Attempts to measure Everest have yielded results ranging from 29,000 to 29,035 feet. Radhanath Sikdar, an Indian mathematician and surveyor, was the first to identify Everest as the world's highest peak in 1852, using trigonometric calculations based on measurements of "Peak XV" (as it was then known) made with theodolites from 150 miles (240 kilometers) away in India. Measurement could not be made from closer due to a lack of access to Nepal. "Peak XV" was found to be exactly 29,000 feet (8,839 m) high, but was publicly declared to be 29,002 feet (8,840 m). The arbitrary addition of 2 feet (0.6 m) was to avoid the impression that an exact height of 29,000 feet was nothing more than a rounded estimate.

The mountain was found to be 29,029 feet (8,848 meters) high, although there is some variation in the measurements. The mountain K2 comes in second at 28,251 feet (8,611 meters) high. On May 22, 2005. the People's Republic of China's Everest Expedition Team ascended to the top of the mountain. After several months' complicated measurement and calculation, on October 9, 2005, the PRC's State Bureau of Surveying and Mapping officially announced the height of Everest as 29,017.16 ± 0.69 feet (8,844.43 ± 0.21 meters). They claimed it was the most accurate measurement to date. But this new height is based on the actual highest point of rock and not on the snow and ice that sits on top of that rock on the summit. So, in keeping with the practice used on Mont Blanc and Khan Tangiri Shyngy, it is not shown here.

In May 1999, an American Everest Expedition, directed by Bradford Washburn, anchored a GPS unit into the highest bedrock. A rock-head elevation of 29,035 feet (8,850 meters), and a snow/ice elevation 3 ft (i meter) higher, were obtained via this device. Nepal, however, did not officially recognize this survey, and the discrepancy with the above mentioned 2005 Chinese survey is significantly greater than the surveys' claimed accuracy. Meanwhile, it is thought that the plate tectonics of the area are adding to the height and moving the summit north-eastwards.

Everest is the mountain whose summit attains the greatest distance above sea level. Two other mountains are sometimes claimed as alternative "tallest mountains on Earth." Mauna Kea in Hawaii is tallest when measured from its base; it rises about 6.3 miles (over 10,203 meters) when measured from its base on the mid-Pacific ocean floor, but only attains 13,796 feet (4,205 meters) above sea level. The summit of Chimborazo, a volcano in Ecuador is 7,113 feet (2,168 meters) farther from the Earth's center than that of Everest, because the Earth bulges at the Equator. However, Chimborazo attains a height of 20,561 feet (6,267 meters), and by this criterion it is not even the highest peak of the Andes mountains.

The deepest spot in the ocean is deeper than Everest is high: the Challenger Deep, located in the Mariana Trench, is so deep that if Everest were to be placed into it there would be more than 1.25 miles (2 kilometers) of water covering it.

Additionally, the Mount Everest region, and the Himalaya mountains in general, are thought to be experiencing ice-melt due to global warming. In a warming study, the exceptionally heavy southwest summer monsoon of 2005 is consistent with continued warming and augmented convective uplift on the Tibetan plateau to the north.

Climbing Everest

Death zone

A death zone is typically any area classified as higher than 8,000 meters (or 24,000 feet), and while all death zones deserve their moniker, Everest's is particularly brutal. Temperatures can dip to very low levels, resulting in frostbite of any body part exposed to the air. Because temperatures are so low, snow is well-frozen in certain areas and death by slipping and falling can also occur. High winds at these altitudes on Everest are also a potential threat to climbers. The atmospheric pressure at the top of Everest is about a third of sea level pressure, meaning there is about a third as much oxygen available to breathe as at sea level.

Well over 200 people have died on the mountain. The conditions on the mountain are so difficult that most of the corpses have been left where they fell; some of them are easily visible from the standard climbing routes. In 2016 at least 200 corpses were still on the mountain, some of them even serving as landmarks.[5]

A 2008 study revealed that most deaths on Everest occur in the "death zone" above 8,000 meters. They also noted that the majority occurred during descents from the summit. [6]

Climbing routes

Mt. Everest has two main climbing routes, the southeast ridge from Nepal and the northeast ridge from Tibet, as well as other less frequently climbed routes. Of the two main routes, the southeast ridge is technically easier and is the more frequently used route. It was the route used by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay in 1953, and the first recognized of fifteen routes to the top by 1996. This was, however, a route decision dictated more by politics than by design, as the Chinese border was closed to foreigners in 1949. Reinhold Messner of Italy summited the mountain solo for the first time, without supplementary oxygen or support, on the more difficult Northwest route via the North Col, a high mountain pass, to the North Face and the Great Couloir, on August 20, 1980. He climbed for three days entirely alone from his base camp at 19,500 feet (6500 meters). This route has been noted as the eighth climbing route to the summit.

Most attempts are made during April and May, before the summer monsoon season. A change in the jet stream at this time of year reduces the average wind speeds high on the mountain. While attempts are sometimes made after the monsoons in September and October, the additional snow deposited by the monsoons and the less stable weather patterns make climbing more difficult.

Southeast ridge

The ascent via the southeast ridge begins with a trek to Base Camp on the Khumbu Glacier at 17,600 feet (5,380 meters) on the south side of Everest, in Nepal. Expeditions usually fly into Lukla from Kathmandu. Climbers then hike to Base Camp, which usually takes six to eight days, allowing for proper altitude acclimatization in order to prevent altitude sickness. Climbing equipment and supplies are carried to Base Camp by yaks, yak hybrids, and porters. When Hillary and Tenzing climbed Everest in 1953, they started from Kathmandu Valley, as there were no roads further east at that time.

Climbers spend a couple of weeks in Base Camp, acclimatizing to the altitude. During that time, Sherpas and some expedition climbers set up ropes and ladders in the treacherous Khumbu Icefall. Seracs (ice pinacles), crevasses, and shifting blocks of ice make the ice-fall one of the most dangerous sections of the route. Many climbers and Sherpas have been killed in this section. To reduce the hazard, climbers usually begin their ascent well before dawn when the freezing temperatures glue ice blocks in place. Above the ice-fall is Camp I, or Advanced Base Camp, at 19,900 feet (6,065 meters).

From Camp I, climbers make their way up the Western Cwm to the base of the Lhotse face, where Camp II is established at 21,300 feet (6,500 meters). The Western Cwm is a relatively flat, gently rising glacial valley, marked by huge lateral crevasses in the center that prevent direct access to the upper reaches of the Cwm. Climbers are forced to cross on the far right near the base of Nuptse to a small passageway known as the "Nuptse corner." The Western Cwm is also called the "Valley of Silence" as the topography of the area generally cuts off wind from the climbing route. The high altitude and a clear, windless day can make the Western Cwm unbearably hot for climbers.

From Camp II, climbers ascend the Lhotse face on fixed ropes up to Camp III, located on a small ledge at 24,500 feet (7,740 meters). From there, it is another 1500 feet (500 meters) to Camp IV on the South Col at 26,000 feet (7,920 meters). From Camp III to Camp IV, climbers are faced with two additional challenges: The Geneva Spur and The Yellow Band. The Geneva Spur is an anvil-shaped rib of black rock named by a 1952 Swiss expedition. Fixed ropes assist climbers in scrambling over this snow-covered rock band. The Yellow Band is a section of sedimentary sandstone which also requires about 300 feet of rope for traversing it.

On the South Col climbers enter the death zone. Climbers typically only have a maximum of two or three days they can endure at this altitude for making summit bids. Clear weather and low winds are critical factors in deciding whether to make a summit attempt. If weather does not cooperate within these short few days, climbers are forced to descend, many all the way back down to Base Camp.

From Camp IV, climbers will begin their summit push around midnight with hopes of reaching the summit (still another 3,000 feet above) within 10 to 12 hours. Climbers will first reach "The Balcony" at 27,700 feet (8400 meters), a small platform where they can rest and gaze at peaks to the south and east in the early dawn light. Continuing up the ridge, climbers are then faced with a series of imposing rock steps which usually forces them to the east into waist deep snow, a serious avalanche hazard. At 28,700 feet (8,750 meters), a small, table-sized dome of ice and snow marks the South Summit.

From the South Summit, climbers follow the knife-edge southeast ridge along what is known as the "Cornice traverse" where snow clings to intermittent rock. This is the most exposed section of the climb as a misstep to the left would send one 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) down the southwest face while to the immediate right is the 10,000-foot (3,050 meters) Kangshung face. At the end of this traverse is an imposing 40-foot (12-meter) rock wall called the "Hillary Step" at 28,750 feet (8,760 meters).

Hillary and Tenzing were the first climbers to ascend this step and they did it with primitive, ice-climbing equipment and without fixed ropes. Nowadays, climbers ascend this step using fixed ropes previously set up by Sherpas. Once above the step, it is a comparatively easy climb to the top on moderately angled snow slopes—though the exposure on the ridge is extreme especially while traversing very large cornices of snow. After the Hillary Step, climbers also must traverse a very loose and rocky section that has a very large entanglement of fixed ropes that can be troublesome in bad weather. Climbers typically spend less than a half-hour on "top of the world" as they realize the need to descend to Camp IV before darkness sets in, afternoon weather becomes a serious problem, or supplemental oxygen tanks run out.

Northeast ridge

The northeast ridge route begins from the north side of Everest in Tibet. Expeditions trek to the Rongbuk Glacier, setting up Base Camp at 17,000 feet (5,180 meters) on a gravel plain just below the glacier. To reach Camp II, climbers ascend the medial moraine of the east Rongbuk Glacier up to the base of Changtse at around 20,000 feet (6,100 meters). Camp III (ABC—Advanced Base Camp) is situated below the North Col at 21,300 feet (6,500 meters). To reach Camp IV on the North Col, climbers ascend the glacier to the foot of the Col where fixed ropes are used to reach the North Col at 23,000 feet (7,010 meters). From the North Col, climbers ascend the rocky north ridge to set up Camp V at around 25,500 feet (7,775 meters).

The route goes up the north face through a series of gullies and steepens into downsloping, slabbed terrain before reaching the site of Camp VI at 27,000 feet (8,230 meters). From Camp VI, climbers will make their final summit push. Climbers must first make their way through three rock bands known as First Step, Second Step, and the Third Step, which end at 28,870 feet. Once above these steps, the final summit slopes (50 to 60 degrees) to the top.

Permits Required

Mountain climbers are a significant source of tourist revenue for Nepal; they range from experienced mountaineers to relative novices who count on their paid guides to get them to the top. The Nepalese government also requires a permit from all prospective climbers; this carries a heavy fee, often more than $25,000 per person.

Recent events and controversies

During the 1996 climbing season, fifteen people died trying to reach the summit. On May 10, a storm stranded several climbers between the summit and the safety of Camp IV, killing five on the south side. Two of the climbers were highly experienced climbers who were leading paid expeditions to the summit. The disaster gained wide publicity and raised questions about the commercialization of Everest.

Journalist Jon Krakauer, on assignment from Outside magazine, was also in the doomed party, and afterward published the bestseller Into Thin Air, which related his experience. Anatoli Boukreev, a guide who felt impugned by Krakauer's book, co-authored a rebuttal book called The Climb. The dispute sparked a large debate within the climbing community. In May 2004, Kent Moore, a physicist, and John L. Semple, a surgeon, both researchers from the University of Toronto, told New Scientist magazine that an analysis of weather conditions on that day suggested that freak weather caused oxygen levels to plunge by around 14 percent.

During the same season, climber and filmmaker David Breashears and his team filmed the IMAX feature Everest on the mountain. The 70-mm IMAX camera was specially modified to be lightweight enough to carry up the mountain, and to function in the extreme cold with the use of particular greases on the mechanical parts, plastic bearings, and special batteries. Production was halted as Breashears and his team assisted the survivors of the May 10 disaster, but the team eventually reached the top on May 23, and filmed the first large format footage of the summit. On Breashears' team was Jamling Tenzing Norgay, the son of Tenzing Norgay, following in his father's footsteps for the first time. Also on his team was Ed Viesturs of Seattle, Washington, who summited without the use of supplemental oxygen, and Araceli Seqarra, who became the first woman from Spain to summit Everest.

The storm's impact on climbers on the mountain's other side, the North Ridge, where several climbers also died, was detailed in a first-hand account by British filmmaker and writer, Matt Dickinson, in his book The Other Side of Everest.

2003—50th anniversary of first ascent

The year 2003 marked the 50th anniversary of the first ascent, and a record number of teams, and some very distinguished climbers, attempted to climb the mountain this year. Several record attempts were attempted, and achieved:

Dick Bass—the first person to climb the seven summits, and who first stood atop Everest in 1985 at 55 years old (making him the oldest person at that time to do so) returned in 2003 to attempt to reclaim his title. At 73, he would have reclaimed this honor, but he made it to ABC only. Dick's team mates included the renowned American climbers Jim Wickwire and John Roskelley.

Outdoor Life Network Expendition—OLN staged a high-profile, survivor-style television series where the winners got the chance to climb Everest. Conrad Anker and David Breashears were commentators on this expedition.

Adventure Peaks Expedition—Walid Abuhaidar and Philip James attempted to become the youngest American and British climbers to climb the North Face, but their expeditions were cut short when one of their team mates fell and broke his leg on the summit ridge at a height of approximately 25,800 feet (8,600 meters). The ensuing rescue was claimed to be the highest-altitude rescue. A documentary is currently being produced on this expedition.

2005—Helicopter landing

On May 14, 2005, pilot Didier Delsalle of France landed a Eurocopter AS 350 B3 Helicopter on the summit of Mount Everest and remained there for two minutes (his rotors were continually engaged; this is known as a "hover landing"). His subsequent take-off set the world record for highest take-off of a rotorcraft—a record that, of course, cannot be beaten. Delsalle had also performed a take-off two days earlier from the South Col, leading to some confusion in the press about the validity of the summit claim. This event does not count as an "ascent" in the usual fashion.

David Sharp controversy

Double-amputee climber Mark Inglis revealed in an interview with the press on May 23, 2006, that his climbing party, and many others, had passed a distressed climber, David Sharp, on May 15, sheltering under a rock overhang 1350 feet (450 meters) below the summit, without attempting a rescue. The revelation sparked wide debate on climbing ethics, especially as applied to Everest. The climbers who left him said that the rescue efforts would be useless and only cause more deaths because of how many people it would have taken to pull him off. Much of this controversy was captured by the Discovery Channel while filming the television program Everest: Beyond the Limit. The issue of theft also became part of the controversy. Vitor Negrete, the first Brazilian to climb Everest without oxygen and part of David Sharp's party, died during his descent, and theft from his high-altitude camp may have contributed.

As this debate raged, on May 26, Australian climber Lincoln Hall was found alive, after being declared dead the day before. He was found by a party of four climbers who, giving up their own summit attempt, stayed with Hall and descended with him and a party of 11 Sherpas sent up to carry him down. Hall later fully recovered.

Bottled oxygen controversy

Most expeditions use oxygen masks and tanks above 26,246 feet (8,000 meters), with this region known as the death zone. Everest can be climbed without supplementary oxygen, but this increases the risk to the climber. Humans do not think clearly with low oxygen, and the combination of severe weather, low temperatures, and steep slopes often require quick, accurate decisions.

The use of bottled oxygen to ascend Mount Everest has been controversial. British climber George Mallory described the use of such oxygen as unsportsmanlike, but he later concluded that it would be impossible to reach the summit and consequently used it. Mallory, who attempted the peak three times in the 1920s, is perhaps best known for his response to a journalist as to why he was climbing Everest. "Because it is there," was his answer. When Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary made the first successful summit in 1953, they used bottled oxygen. For the next twenty-five years, bottled oxygen was considered standard for any successful summit.

Reinhold Messner was the first climber to break the bottled oxygen tradition and in 1978, with Peter Habeler, made the first successful climb without it. Although critics alleged that he sucked mini-bottles of oxygen—a claim that Messner denied—Messner silenced them when he summited the mountain, without supplemental oxygen or support, on the more difficult northwest route, in 1980. In the aftermath of Messner's two successful ascents, the debate on bottled oxygen usage continued.

The aftermath of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster further intensified the debate. Jon Krakauer's Into Thin Air (1997) expressed the author's personal criticisms of the use of bottled oxygen. Krakauer wrote that the use of bottled oxygen allowed otherwise unqualified climbers to attempt to summit, leading to dangerous situations and more deaths. The May 10 disaster was partially caused by the sheer number of climbers (33 on that day) attempting to ascend, causing bottlenecks at Hillary Step and delaying many climbers, most of whom summited after the usual 2:00 p.m. turnaround time. Krakauer proposed banning bottled oxygen except for emergency cases, arguing that this would both decrease the growing pollution on Everest, and keep marginally qualified climbers off the mountain. The 1996 disaster also introduced the issue of the guide's role in using bottled oxygen.

While most climbers in the mountaineering community support Krakauer's point of view, others feel that there is only a small set of climbers, such as Anatoli Boukreev and Ed Viesturs, who can climb without supplementary oxygen and still function well. Most climbers agree that a guide cannot directly help clients if he or she cannot concentrate or think clearly, and thus should use bottled oxygen.

2014 avalanche and Sherpa strike

On April 18, 2014, in one of the worst disasters to ever hit the Everest climbing community up to that time, 16 Sherpas died in Nepal due to the avalanche that swept them off Mount Everest. Thirteen bodies were recovered within two days, while the remaining three were never recovered due to the great danger of performing such an expedition. Sherpa guides were angered by what they saw as the Nepalese government's meager offer of compensation to victims' families, initially only the equivalent of $400 to pay funeral costs, and threatened a "strong protest" or strike. One of the issues that was triggered was pre-existing resentment that had been building over unreasonable client requests during climbs.

On April 22, the Sherpas announced they would not work on Everest for the remainder of 2014 as a mark of respect for the victims. Most climbing companies pulled out in respect for the Sherpa people mourning the loss.

Life forms on the mountain

Euophrys omnisuperstes, a minute, black jumping spider, has been found at elevations as high as 20,100 feet (6,700 meters), possibly making it the highest altitude, confirmed, permanent resident on earth. They lurk in crevices and possibly feed on frozen insects that have been blown there by the wind. It should be noted that there is a high likelihood of microscopic life at even higher altitudes.

Birds, such as the bar-headed goose have been seen flying at the higher altitudes of the mountain, while others such as the Chough have been spotted at high levels on the mountain itself, scavenging on food, or even corpses, left over by climbing expeditions.

Notes

- ↑ Based on elevation of snow cap, not rock head. For more details, see Measurement.

- ↑ The position of the summit of Everest on the international border is clearly shown on detailed topographic mapping, including official Nepalese mapping.

- ↑ Borgna Brunner, Mortals on Mount Olympus A history of climbing Mount Everest. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ↑ Time Line EverestHistory.com. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ↑ Rachel Nuwer, Death in the Clouds: The Problem with Everest's 200+ Bodies BBC, October 9, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- ↑ Massachusetts General Hospital, Why Climbers Die On Mount Everest Science Daily, December 15, 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gillman, Leni. Everest: Eighty Years of Triumph and Tragedy. Mountaineers Books, 2001. ISBN 978-0898867800

- Krakauer, John. Into Thin Air: A Personal Account of the Mt. Everest Disaster. Anchor, 1999. ISBN 978-0385494786

- Messner, Reinhold. Everest. Baton Wicks Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-1898573456

- Ortner, Sherry. Life and Death on Mt. Everest: Sherpas and Himalayan Mountaineering. Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0691074481

External Links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Brunner, Borgna. "A history of climbing Mount Everest" Everest Almanac

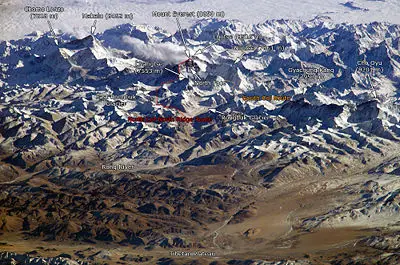

- "Zoomable satellite image of Everest" Google Maps

- "Everest online" NOVA Online Adventure

- "Everest" Summitpost.org

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.