Chola Dynasty

- "Chola" redirects here.

| ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

The Chola Dynasty (Tamil: சோழர் குலம், IPA: ['ʧoːɻə]), a Tamil dynasty, ruled primarily in southern India until the thirteenth century. The dynasty originated in the fertile valley of the Kaveri River. Karikala Chola stands as the most famous among the early Chola kings, while Rajaraja Chola, Rajendra Chola and Kulothunga Chola I ruled as notable emperors of the medieval Cholas.

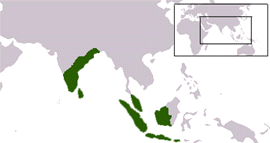

The Cholas reached the height of their power during the tenth, eleventh and twelfth centuries. Under Rajaraja Chola I (Rajaraja the Great) and his son Rajendra Chola, the dynasty became a military, economic and cultural power in Asia. The Chola territories stretched from the islands of the Maldives in the South to as far North as the banks of the Godavari River in Andhra Pradesh. Rajaraja Chola conquered peninsular South India, annexed parts of Sri Lanka and occupied the islands of the Maldives. Rajendra Chola sent a victorious expedition to North India that touched the river Ganga and defeated the Pala ruler of Pataliputra, Mahipala. He also successfully raided kingdoms of the Malay Archipelago. The power of the Cholas declined around the twelfth century with the rise of the Pandyas and the Hoysala, eventually coming to an end towards the end of the thirteenth century.

The Cholas left behind a lasting legacy. Their patronage of Tamil literature and their zeal in building temples have resulted in some great works of Tamil literature and architecture. The Chola kings avidly built temples, envisioned them in their kingdoms not only as places of worship but also as centers of economic activity. They pioneered a centralized form of government and established a disciplined bureaucracy.

Origins

Little information exists regarding the origin of the Chola Dynasty. Mention in ancient Tamil literature and in inscriptions provides evidence of the antiquity of this dynasty. Later medieval Cholas also claimed a long and ancient lineage to their dynasty.

Mentions in the early Sangam literature (c. 150) makes a correlation between the evidence on foreign trade found in the poems and the writings by ancient Greek and Romans such as Periplus established the age of Sangam.[2] indicate that the earliest kings of the dynasty antedated 100 C.E. Parimelalagar, the annotator of the Tamil classic Tirukkural, might represent the name of an ancient clan. Most scholars hold the view, like Cheras and Pandyas, that the name represents the ruling family or clan of immemorial antiquity.[3][4]

Scant authentic written evidence exists on the history of Cholas. Historians during the past 150 years have gleaned a lot of knowledge on the subject from a variety of sources such as ancient Tamil Sangam literature, oral traditions, religious texts, temple and copperplate inscriptions. The early Tamil literature of the Sangam Period constitutes the main source for the available information of the early Cholas.[5] The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (Periplus Maris Erythraei) present brief notices on the Chola country and its towns, ports and commerce.[6] Periplus represents a work by an anonymous Alexandrian merchant, written in the time of Domitian (81 – 96 C.E.) and contains minimal information of the Chola country. Writing half a century later, the geographer Ptolemy gives more detail about the Chola country, its port and its inland cities.[7] Mahavamsa, a Buddhist text, recounts a number of conflicts between the inhabitants of Ceylon and the Tamil immigrants.[8] The Pillars of Ashoka (inscribed 273 B.C.E. – 232 B.C.E.) inscriptions mention Cholas among the kingdoms which, although independent of Ashoka, existed on friendly terms with him.[9][10]

Etymology of Chola

Many historians and linguists have agreed upon the etymology of the word Chola as derived from the Tamil word Sora or Chora. Numerous inscriptions confirm the name of the Dynasty as Chora or Sora but pronounced as Chola.[11] The shift from 'r' to 'l' has also been validated and Sora or Chora in Tamil becomes Chola in Sanskrit and Chola or Choda in Telugu.[12][13]

History

The history of the Cholas falls naturally into four periods: the early Cholas of the Sangam literature, the interregnum between the fall of the Sangam Cholas and the rise of the medieval Cholas under Vijayalaya (c. 848), the dynasty of Vijayalaya, and finally the Chalukya Chola dynasty of Kulothunga Chola I from the third quarter of the eleventh century.[14]

Early Cholas

Sangam literature offers the first tangible evidence of the earliest Chola kings. Scholars generally agree that the literature belongs to the first few centuries of the common era although they still dispute the internal chronology of the literature, leaving us without a connected account of the history of the period. The Sangam literature offers an abundance of kings and princes names, and of the poets who extolled them. A rich literature depicts the life and work of those people, yet without a hint of time periods.

Legends about mythical Chola kings fill the Sangam literature. The Cholas considered themselves descended from the sun.[15] Those myths speak of the Chola king Kantaman, a supposed contemporary of the sage Agastya, whose devotion brought the river Kaveri into existence.[16] Two names stand out prominently from among those Chola kings known to have existed, who feature in Sangam literature: Karikala Chola and Kocengannan. Uncertainity about the order of succession, of fixing their relations with one another and with many other princelings of about the same period remains.[17] Urayur (now in part of Thiruchirapalli) served as their oldest capital.

Interregnum

Few records describe the transition period of around three centuries from the end of the Sangam age (c. 300) to the era Pandyas and Pallavas dominate the Tamil country. An obscure dynasty, the Kalabhras, invaded the Tamil country, displaced the existing kingdoms and ruled for around three centuries. The Pallavas and the Pandyas, in turn, had been displaced during the sixth century. The fate of the Cholas during the succeeding three centuries until the accession of Vijayalaya in the second quarter of the ninth century remains a mystery.

Epigraphy and literature provide a few faint glimpses of the transformations that came over that ancient line of kings during the long interval. Certainly the power of the Cholas fell to its lowest ebb and that of the Pandyas and Pallavas rose to the north and south of them.<re>Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 102.</ref> The dynasty sought refuge and patronage under their more successful rivals.[18] The Pallavas and Pandyas seem to have left the Cholas alone for the most part; possibly out of regard for their reputation. They accepted Chola princesses in marriage and employed in their service Chola princes willing to accept it.[19] The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang, who spent several months in Kanchipuram during 639 – 640 writes about the 'kingdom of Culi-ya'.[20] Numerous inscriptions of Pallavas, Pandyas and Chalukya of the period mention conquering 'the Chola country'.[21] Despite that loss in influence and power, the Cholas most likely kept control of some of the territory around Urayur, their old capital. Vijayalaya, when he rose to prominence, hailed from that geographical area.

Around the seventh century, a Chola kingdom flourished in present-day Andhra Pradesh. Those Telugu Cholas traced their descent to the early Sangam Cholas.[22] Nothing definite has been discovered of their connection to the early Cholas. Possibly a branch of the Tamil Cholas migrated north during the time of the Pallavas to establish a kingdom of their own, away from the dominating influences of the Pandyas and Pallavas.

Medieval Cholas

While scant reliable information on the Cholas during the period between the early Cholas and Vijayalaya dynasties exists, an abundance of materials from diverse sources on the Vijayalaya and the Chalukya Chola dynasties has been discovered. A large number of stone inscriptions by the Cholas themselves and by their rival kings, Pandyas and Chalukyas, and copper-plate grants, have been instrumental in constructing the history of Cholas of that period.[23]

Around 850, Vijayalaya rose from obscurity to take an opportunity arising out of a conflict between Pandyas and Pallavas,[24] captured Thanjavur and eventually established the imperial line of the medieval Cholas.[25]

The Chola dynasty reached the peak of its influence and power during the medieval period. Great kings such as Rajaraja Chola I and Rajendra Chola I occupied the throne, and through their leadership and vision extended the Chola kingdom beyond the traditional limits of a Tamil kingdom. At its peak, the Chola Empire stretched from the island of Sri Lanka in the south to the Godavari basin in the north.[26] The kingdoms along the east coast of India up to the river Ganges acknowledged Chola suzerainty. Chola navies invaded and conquered Srivijaya in the Malayan archipelago.[27] The report on the conquest of Srivijaya might be an exaggeration.[28]

Throughout that period, who attempted to overthrow the Chola occupation of Lanka, the ever-resilient Sinhalas constantly troubled the Cholas. In addition, the Pandya princes tried to win independence for their traditional territories, and the Chalukyas ambitions grew in the western Deccan. That period saw constant warfare between the Cholas and those antagonists. A balance of power existed between the Chalukyas and the Cholas with a tacit acceptance of the Tungabhadra River as the boundary between the two empires. The bone of contention between those two powers remained the growing Chola influence in the Vengi kingdom.

Chalukya Cholas

Marital and political alliances between the Eastern Chalukya kings based around Vengi located on the south banks of the River Godavari began during the reign of Rajaraja following his invasion of Vengi. Rajaraja Chola's daughter married prince Vimaladitya. Rajendra Chola's daughter married an Eastern Chalukya prince Rajaraja Narendra.

An assassin killed Virarajendra Chola's son Athirajendra Chola in a civil disturbance in 1070 and Kulothunga Chola I ascended the Chola throne starting the Chalukya Chola dynasty. Kulothunga was a son of the Vengi king Rajaraja Narendra.

The Chalukya Chola dynasty saw capable rulers in Kulothunga Chola I and Vikrama Chola; although the decline of the Chola power practically started during that period. The Cholas lost control of the island of Lanka, driven out by the revival of Sinhala power. Around 1118 they lost the control of Vengi to Western Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI and Gangavadi (southern Mysore districts) to the growing power of Hoysala Vishnuvardhana, a Chalukya feudatory. In the Pandya territories, the lack of a controlling central administration prompted a number of claimants to the Pandya throne to cause a civil war, involving the Sinhalas and the Cholas by proxy. During the last century of the Cholas, a permanent Hoysala army stationed in Kanchipuram to protect them from the growing influence of the Pandyas.

The Cholas, under Rajendra Chola III, experienced continuous trouble. At the close of the twelfth century, the growing influence of the Hoysalas replaced the declining Chalukyas as the main player in the north. The local feudatories became sufficiently confident to challenge the central Chola authority. One feudatory, the Kadava chieftain Kopperunchinga I, even held the Chola king hostage for sometime. Assaults beseiged the Cholas from within and without. The Pandyas in the south had risen to the rank of a great power. The Hoysalas in the west threatened the existence of the Chola empire. Rajendra tried to survive by aligning with the two powers in turn. At the close of Rajendra’s reign, the Pandyan Empire reached its height of prosperity and had taken the place of the Chola empire in the eyes of the foreign observers. 1279 marked the last recorded date of Rajendra III. Evidence that another Chola prince immediately followed Rajendra has never been found. The Pandyan empire completely overshadowed the Chola empire, though many small chieftains continued to claim the title "Chola" well into the fifteenth century.

Government and society

Chola country

According to Tamil tradition, the old Chola country comprised the region that includes the modern-day Tiruchirapalli District, and the Thanjavur District in Tamil Nadu state. The river Kaveri and its tributaries dominate the landscape of generally flat country that gradually slopes towards the sea, unbroken by major hills or valleys. The river Kaveri, also known as Ponni (golden) river, had a special place in the culture of Cholas. The unfailing annual floods in the Kaveri marked an occasion for celebration, Adiperukku, in which the whole nation took part, from the king to the lowest peasant.

Kaverippattinam on the coast near the Kaveri delta constituted a major port town. Ptolemy knew of that and the other port town of Nagappattinam as the most important centres of Cholas.[29] Those two cosmopolitan towns became hubs of trade and commerce and attracted many religious faiths, including Buddhism.[30] Roman ships found their way in to those ports. Roman coins dating from the early centuries of the common era have been found near the Kaveri delta.[31]

Thanjavur, Urayur, and Kudanthai, now known as Kumbakonam, represent the other major towns. After Rajendra Chola moved his kingdom to Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Thanjavur lost its importance. The later Chola kings of the Chalukya Chola dynasty moved around their country frequently and made cities such as Chidambaram, Madurai and Kanchipuram their regional capitals.

Nature of government

In the age of the Cholas, the whole of South India came, for the first time, brought under a single government,[32] when a reform movement attempted to face and solve the problems of public administration. The Cholas system of practiced a monarchical government, as in the Sangam age, although little in common existed between the primitive and somewhat tribal chieftaincy of the earlier time and the almost Byzantine royalty—Rajaraja Chola—and his successors with its numerous palaces, and the pomp and circumstance associated with the royal court.

Between 980, and c. 1150, the Chola Empire embraced the entire south Indian peninsula, extending east to west from coast to coast, and bounded to the north by an irregular line along the Tungabhadra river and the Vengi frontier. Although Vengi had a separate political existence, its intimate connection to the Chola Empire extended, for all practical purposes, the Chola dominion to the banks of the Godavari river.[33]

Thanjavur and later Gangaikonda Cholapuram served as the imperial capitals, while both Kanchipuram and Madurai constituted regional capitals where courts occasionally convened. The king presided as the supreme commander and a benevolent dictator.[34] His administrative role consisted of issuing oral commands to responsible officers when receiving representations.[35] A powerful bureaucracy assisted the king in the tasks of administration and in executing his orders. Due to the lack of a legislature or a legislative system in the modern sense, the fairness of king’s orders dependent on the goodness of the man and in his belief in Dharma—a sense of fairness and justice. All Chola kings built temples and endowed great wealth to them. The temples acted not only as places of worship but as centres of economic activity, benefiting their entire community.[36]

Local government

Every village made a self-governing unit. A number of villages constituted a larger entity known as a Kurram, Nadu, or Kottram,, depending on the area. A number of Kurrams constituted a valanadu. Those structures underwent constant change and refinement throughout the Chola period.[37]

Justice represented mostly a local matter in the Chola Empire with minor disputes settled at the village level. Punishment for minor crimes came in the form of fines or a direction for the offender to donate to some charitable endowment. Even crimes such as manslaughter or murder received fines as punishment. The king himself heard and decided crimes of the state, such as treason with the typical punishment either execution or the confiscation of property.[38]

Foreign trade

The Cholas excelled in foreign trade and maritime activity, extending their influence overseas to China and Southeast Asia. Towards the end of the ninth century, southern India had developed extensive maritime and commercial activity. The Cholas, possessing parts of both the west and the east coasts of peninsular India, stood at the forefront of those ventures. The Tang Dynasty of China, the Srivijaya empire in the Malayan archipelago under the Saliendras, and the Abbasid Kalifat at Baghdad emerged as the main trading partners.[40]

Chinese Song Dynasty reports record that an embassy from Chulian (Chola) reached the Chinese court in the year 1077, the king of the Chulien at the time called Ti-hua-kia-lo.[41] Those syllables might denote "Deva Kulo[tunga]" (Kulothunga Chola I). That embassy embodied a trading venture, highly profitable to the visitors, who returned with 81,800 strings of copper coins in exchange for articles of tributes, including glass articles and spices.[42]

A fragmentary Tamil inscription found in Sumatra cites the name of a merchant guild Nanadesa Tisaiyayirattu Ainnutruvar (literally, "the five hundred from the four countries and the thousand directions"), a famous merchant guild in the Chola country.[43] The inscription dated 1088, indicating an active overseas trade during the Chola period.

Chola society

Scant information exists on the size and the density of the population during the Chola reign. The overwhelming stability in the core Chola region enabled the people to lead productive and contented lives. Only one recorded instance of civil disturbance exists during the entire period of Chola reign,[44] although reports of widespread famine caused by natural calamities.

The quality of the inscriptions of the regime indicates a presence of high level of literacy and education in the society. Court poets wrote, and talented artisans engraved, the text in those inscriptions. People considered education in the contemporary sense unimportant. Circumstantial evidence suggests that some village councils organized schools to teach the basics of reading and writing to children, although evidence of systematic educational system for the masses has never been found.[45] Vocational education took the form of apprenticeship, with the father passing on his skills to his sons. Tamil served as the medium of education for the masses; the Brahmins alone had Sanskrit education. Religious monasteries (matha or gatika), supported by the government, emerged as centers of learning.[46][47]

Cultural contributions

Under the Cholas, the Tamil country reached new heights of excellence in art, religion and literature. In all of those spheres, the Chola period marked the culmination of movements that had begun in an earlier age under the Pallavas. Monumental architecture in the form of majestic temples and sculpture in stone and bronze reached a finesse never before achieved in India.

The Cholas excelled in maritime activity in both military and the mercantile fields. Their conquest of Kadaram (Kedah) and the Srivijaya, and their continued commercial contacts with the Chinese Empire, enabled them to influence the local cultures. Many of the surviving examples of the Hindu cultural influence found today throughout the Southeast Asia owe much to the legacy of the Cholas.[48]

Art

The Cholas continued the temple-building traditions of the Pallava dynasty and contributed significantly to the Dravidian temple design. They built numerous temples throughout their kingdom such as the Brihadeshvara Temple. Aditya I built a number of Siva temples along the banks of the river Kaveri. Those temples ranged from small to medium scale until the end of the tenth century.[49]

Temple building received great impetus from the conquests and the genius of Rajaraja Chola and his son Rajendra Chola I (r. 1014 C.E.). The maturity and grandeur to which the Chola architecture had evolved found expression in the two temples of Tanjavur and Gangaikondacholapuram. The magnificent Siva temple of Thanjavur, completed around 1009, stands as a fitting memorial to the material achievements of the time of Rajaraja. The largest and tallest of all Indian temples of its time, the temple sits at the apex of South Indian architecture.[50]

The temple of Gangaikondacholapuram, the creation of Rajendra Chola, sought to exceed its predecessor in every way. Completed around 1030, only two decades after the temple at Thanjavur and in much the same style, the greater elaboration in its appearance attests the more affluent state of the Chola Empire under Rajendra.[51] The temple complex is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Its remarkable sculptures and bronzes sets the Chola period apart. Among the existing specimens in museums around the world and in the temples of South India may be seen many fine figures of Siva in various forms, such as Vishnu and his consort Lakshmi, and the Siva saints. Though conforming generally to the iconographic conventions established by long tradition, the sculptors worked with great freedom in the eleventh and twelfth centuries to achieve a classic grace and grandeur. The best example of that appears in the form of Nataraja the Divine Dancer.[52][53]

Literature

The age of the Imperial Cholas (850–1200) represented the golden age of Tamil culture, marked by the importance of literature. Chola inscriptions cite many works, although trageically most of them have been lost, including Rajarajesvara Natakam- a work on drama, Viranukkaviyam by one Virasola Anukkar, and Kannivana Puranam, a work of popular nature.[54]

The revival of Hinduism from its nadir during the Kalabhras spurred the construction of numerous temples and those in turn generated Saiva and Vaishnava devotional literature. Jain and Buddhist authors flourished as well, although in fewer numbers than in previous centuries. Jivaka-chintamani by Tirutakkadevar and Sulamani by Tolamoli numbered among notable by non-Hindu authors. The art of Tirutakkadevar embodies the qualities of great poetry.[55] has been considered as the model for Kamban for his masterpiece Ramavatharam.

Kamban flourished during the reign of Kulothunga Chola III.[56] His Ramavatharam representes the greatest epic in Tamil Literature, and although the author states that he followed Valmiki, his work trancends a mere translation or simple adaptation of the Sanskrit epic: Kamban imports into his narration the color and landscape of his own time; his description of Kosala presents an idealized account of the features of the Chola country.

Jayamkondar’s masterpiece Kalingattuparani provides an example of narrative poetry that draws a clear boundary between history and fictitious conventions. That describes the events during Kulothunga Chola I’s war in Kalinga and depicts not only the pomp and circumstance of war, but the gruesome details of the field. The famous Tamil poet Ottakuttan lived as a contemporary of Kulothunga Chola I. Ottakuttan wrote Kulothunga Solan Ula a poem extolling the virtues of the Chola king. He served at the courts of three of his successors.

The impulse to produce devotional religious literature continued into the Chola period and the arrangement of the Saiva canon into eleven books represented the work of Nambi Andar Nambi, who lived close to the end of 10th century. Relatively few works on Vaishnavite religion had been composed during the Chola period, possibly because of the apparent animosity towards the Vaishnavites by the Chaluka Chola monarchs.[57]

Religion

In general, Cholas professed Hinduism. Throughout their history, the rise of Buddhism and Jainism left them unswayed, as also the kings of the Pallava and Pandya dynasties. Even the early Cholas followed a version of the classical Hindu faith. Evidence in Purananuru points to Karikala Chola’s faith in the Vedic Hinduism in the Tamil country.[58] Kocengannan, another early Chola, had been celebrated in both Sangam literature and in the Saiva canon as a saint.

Later Cholas also stood staunchly as Saivites, although they displayed a sense of toleration towards other sects and religions. Parantaka I and Sundara Chola endowed and built temples for both Siva and Vishnu. Rajaraja Chola I even patronised Buddhists, and built the Chudamani Vihara (a Buddhist monastery) in Nagapattinam at the request of the Srivijaya Sailendra king.[59]

During the period of Chalukya Cholas, instances of intolerance towards Vaishnavites—especially towards Ramanuja, the leader of the Vaishnavites had been recorded. That intolerance led to persecution and Ramanuja went into exile in the Chalukya country. He led a popular uprising that resulted in the assassination of Athirajendra Chola. Kulothunga Chola II reportedly removed a statue of Vishnu from the Siva temple at Chidambaram. Ample evidence, from the inscriptions, indicates that Kulothunga II lived as a religious fanatic who wanted to upset the camaraderie between Hindu faiths in the Chola country.[60]

In popular culture

The history of the Chola dynasty has inspired many Tamil authors to produce literary and artistic creations during the last several decades. Those works of popular literature have helped continue the memory of the great Cholas in the minds of the Tamil people. The popular Ponniyin Selvan (The son of Ponni), a historical novel in Tamil written by Kalki Krishnamurthy (September 9, 1899 – December 5, 1954), represents the most important work of that genre. Written in five volumes, the books narrate the story of Rajaraja Chola. Ponniyin Selvan deals with the events leading up to the ascension of Uttama Chola on the Chola throne. Kalki had cleverly utilised the confusion in the succession to the Chola throne after the demise of Sundara Chola. The Tamil periodical Kalki serialized the book in the mid-1950s. The serialization lasted for nearly five years and every week multitudes awaited its publication with great interest.

Kalki perhaps laid the foundations for that novel in his earlier historical romance Parthiban Kanavu, which dealt with the fortunes of an imaginary Chola prince Vikraman supposed to have lived as a feudatory of the Pallava king Narasimhavarman I during the seventh century. The period of the story lies within the interregnum during which the Cholas declined before Vijayalaya Chola revived their fortune. The Kalki weekly serialized Parthiban Kanavu in the early 1950s.

Sandilyan, another popular Tamil novelist, wrote Kadal Pura, serialized in the Tamil weekly Kumudam in the 1960s. Kadal Pura takes place during the period when Kulothunga Chola I suffered exile from the Vengi kingdom, after denied the throne rightfully his. Kadal Pura speculates the whereabouts of Kulothunga during that period. Sandilyan's earlier work Yavana Rani, written in the early 1960s, uses the life of Karikala Chola as inspiration. More recently, Balakumaran wrote the opus Udaiyar based on the event surrounding Rajaraja Chola's construction of the Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur. In January 2007, Anusha Venkatesh wrote Kaviri mainthan, a novel set in the Chola period and a sequel to Ponniyin Selvan, published by The Avenue Press.

Stage productions based on the life of Rajaraja Chola appeared during the 1950s and in 1973, Shivaji Ganesan acting in a screen adaptation of that play.

The History of the World board game, produced by Avalon Hill, features the Chola.

Notes

- ↑ None of the numerous references that appear in Tamil literature tells us anything of its origin. The Telugu Cholas who claimed to have descended from the early Cholas adapted the lion crest.

- ↑ K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar (Madras: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press, 1955), 106.

- ↑ See Tirukkural poem 955 (வழங்குவ துள்வீழ்ந்தக் கண்ணும் பழங்குடி/பண்பில் தலைப்பிரிதல் இன்று. The annotator Parimelazhagar writes "The charity of people with ancient lineage (such as the Cholas, the Pandyas and the Cheras) are forever generous in spite of their reduced means".

- ↑ Killi (கிள்ளி), Valavan (வளவன்) and Sembiyan (சேம்பியன்) represent other names in common use for the Cholas. Killi perhaps comes from the Tamil kil (கிள்) meaning dig or cleave and conveys the idea of a digger or a worker of the land. That word often forms an integral part of early Chola names like Nedunkilli, Nalankilli and so on, but almost drops out of use in later times. Valavan most probably connects with 'valam' (வளம்) - (fertility) and means owner or ruler of a fertile country. Sembiyan may mean a descendant of Shibi – a legendary hero whose self-sacrifice in saving a dove from the pursuit of a falcon figures among the early Chola legends and forms the subject matter of the Sibi Jataka among the Jataka stories of Buddhism. See: K. A. Nilakanta Sastri, The CōĻas (Madras University historical series, no. 9.) (Madras: University of Madras, 1935), 19–20.

- ↑ The period covered by the Sangam poetry most likely extended only five or six generations - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 3

- ↑ The Periplus refers to the region of the eastern seaboard of South India as Damirica - The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea Ancient History sourcebook (Fordham University). Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Ptolemy mentions the town of Kaveripattinam (under the form Khaberis) - Proceedings, American Philosophical Society 122(6) (1978).

- ↑ Wilhelm Geiger, THE MAHAVAMSA 6th Century B.C.E. to 4th Century AD, translated from the Pali. lakdiva.org. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ The Asokan inscriptions speak of the Cholas in plural, implying that, in his time, more than one Chola existed - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 20.

- ↑ The Edicts of Ashoka, issued around 250 B.C.E. by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, mention the Cholas as recipients of his Buddhist prozelytism: "The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas (5,400–9,600 km) away, where the Greek king Antiochos rules, beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy, Antigonos, Magas and Alexander rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni (Sri Lanka). (Edicts of Ashoka, 13th Rock Edict, S. Dhammika)."

- ↑ A. L. Frothingham, Jr., "Archaeological News." The American Journal of Archaeology and of the History of the Fine Arts 4 (1) (Mar., 1888): 69-125.

- ↑ Baij Nath Puri, India in Classical Greek Writings (Ahmedabad: New Order Book Co., 1963).

- ↑ "The name Coromandel is used for the east coast of India from Cape Comorin to Nellore, or from point Calimere to the mouth of Krihsna. The word is a corrupt form of Choramandala or the Realm of Chora, which is the Tamil form of the title of the Chola dynasty." - A. N. Gupta, Satish Gupta. Sarojini Naidu's Select Poems, with an Introduction, Notes, and Bibliography for Further Study (Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot, 1976).

- ↑ The direct line of Cholas of the Vijayalaya dynasty came to a bloody end with the assassination of Virarajendra Chola. Kulothunga Chola I a distant relation to the main Chola line through marriage ascended the throne in 1070.

- ↑ "செங்கதிர்ச் செல்வன் திருக் குலம் விளக்கும்" - Manimekalai ("Girdle of Gems") (poem 00-10)

- ↑ Seethalai Saathanar, "Manimekalai" ("Girdle of Gems") (22-030).

- ↑ The Sangam Literature and the synchronization with the history of Sri Lanka as given in the Mahavamsa constitute the only evidence for the approximate period of those early kings. Gajabahu I, considered the contemporary of the Chera Senguttuvan, has been placed in the second century. That leads us to date the poems mentioning Senguttuvan and his contemporaries to belong to that period.

- ↑ Pandya Kadungon and Pallava Simhavishnu overthrew the Kalabhras. Acchchutakalaba likely reigned as the last Kalabhra king - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 102.

- ↑ Periyapuranam, a Saiva religious work of twelfth century, tells us of the Pandya contemporary of the saint Tirugnanasambandar who had for his queen a Chola princess.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 102.

- ↑ Copperplate grants of the Pallava Buddhavarman (late fourth century) mention that the king as the 'underwater fire that destroyed the ocean of the Chola army' - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 104–105. Simhavishnu (575–600) seized the Chola country. His Mahendravarman I's inscriptions name him the 'crown of the Chola country'. The Chalukya Pulakesin II, in his inscriptions in Aihole, states that he defeated the Pallavas and brought relief to the Cholas. - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 105.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri postulates that a live connection between the early Cholas and the Renandu Cholas of the Andhra country existed. The northward migration probably took place during the Pallava domination of Simhavishnu. Sastri also categorically rejects the claims that they descended from Karikala Chola - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 107.

- ↑ The Chola inscriptions followed the practice of prefacing the intended text with a historical recounting, in a poetic and ornate style of Tamil, of the main achievements of the reign and the decent of the king and of his ancestors - See South Indian Inscriptions

- ↑ The opportunity for Vijayalaya arose during the battle of Sripurambayam between the Pallava ally Ganga Pritvipati and the Pandya Varaguna.

- ↑ Vijayalaya invaded Thanjavur and defeated the Muttarayar king, feudatory of the Pandyas.

- ↑ Rajendra Chola I completed the conquest of the island of Sri Lanka and captured the Sinhala king Mahinda V prisoner. See Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 194–210.

- ↑ Rajendra's inscriptions first mentioned the kadaram campaign, dating from his fourteenth year. The name of the Srivijaya king was Sangrama Vijayatungavarman -Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 211–220.

- ↑ Stuart Munro-Hay. Nakhon Sri Thammarat: The Archaeology, History and Legends of a Southern Thai Town. (ISBN 9747534738), 18.

- ↑ Ptolomy mentions the markets of Kaverippattinam as Chabaris Emporium in his Geographica.

- ↑ The Buddhist work Milinda Panha, dated to the early Christian era, mentions Kolapttna among the best-known sea ports on the Chola coast - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 23.

- ↑ R. Nagaswamy, Tamil Coins - a study (Madras: Institute of Epigraphy, Tamilnadu State Dept. of Archaeology, 1981]. Tamil Arts Academy. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ The only other time when peninsular India would be brought under one umbrella before the Independence occurred during the Vijayanagara Empire (1336–1614)

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 448.

- ↑ The executive ruled from from legislature or controls. The king ruled by edicts, which generally followed dharma a culturally mediated concept of 'fair and proper' practice. See Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 451, 460–461.

- ↑ For example, the Layden copperplate grant mentioned that Rajaraja issued an oral order for a gift to a Buddhist vihara at Nagapattinam, which a clerk wrote out (… நாம் சொல்ல நம் ஓலை எழுதும்…) - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 461.

- ↑ Some of the output of villages throughout the kingdom went to temples that reinvested some of the wealth accumulated as loans to the settlements. The temple served as a center for redistribution of wealth and contributed towards the integrity of the kingdom - John Keays, India: A History (New York: Grove Press, 2001, ISBN 0802137970), 217–218.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 465.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 477.

- ↑ K.A. Nilakanta Sastri, A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar: from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar (Oxford University Press, 1955), 424–426.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 604.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 316.

- ↑ The Tamil merchants took glassware, camphor, sandalwood, rhinoceros horns, ivory, rose water, asafoetida, spices such as pepper, cloves, etc. See Nilakanta Sastri, 1955, 173.

- ↑ Tamil: நானாதேச திசையாயிரத்து ஐந்நூற்றுவர்

- ↑ —during the short reign of Virarajendra Chola, which possibly had some sectarian roots.

- ↑ Seventeenth century Italian traveler Pietro Della Valle (1623) has given a vivid account of the village schools in South India. Those accounts reflect the system of primary education in existence until the modern times in Tamil Nadu.

- ↑ Rajendra Chola I endowed a large college in which more than 280 students learnt from 14 teachers - Nilakanta Sastri, 1955, 293.

- ↑ The students studied a number of subjects in those colleges, including philosophy (anvikshiki), Vedas (trayi – the threefold Vedas of Rigveda, Yajurveda and Samaveda; the fourth Atharvaveda considered a non-religious text.), economics (vartta), government (dandaniti), grammar, prosody, etymology, astronomy, logic (tarka), medicine (ayurveda), politics (arthasastra), and music. - Nilakanta Sastri, 1955, 292.

- ↑ The great temple complex at Prambanan in Indonesia exhibits a number of similarities with the South Indian architecture. See: Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 709.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1955, 418.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1955, 421.

- ↑ R. Nagaswamy, Gangaikondacholapuram (State Department of Archaeology, Government of Tamilnadu, 1970). Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- ↑ Shiva as Nataraja - Dance and Destruction In Indian Art Exotic India. Retrieved September 3, 2021..

- ↑ The bronze image of Nataraja at the Nagesvara Temple in Kumbakonam represents the largest image known.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 663–664.

- ↑ Sindamani, based on Uttarapurana of Gunabhadra composed in 898,

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 672.

- ↑ Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 681.

- ↑ Purananuru (poem 224) movingly expresses his faith and the grief caused by his passing away.

- ↑ The name of the Sailendra king was Sri Chulamanivarman. The Vihara was named 'Chudamani vihara' in his honor - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 214.

- ↑ An inscription from 1160 states that the custodians of Siva temples who had social intercourse with Vaishnavites would forfeit their property. - Nilakanta Sastri, 1935, 645.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dehejia, Vidya. Art of the imperial Cholas. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990 ISBN 0231071884

- Geiger, Wilhelm, THE MAHAVAMSA 6th Century B.C.E. to 4th Century AD, translated from the Pali by Wilhelm Geiger. lakdiva.org. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Gupta, N., and Satish Gupta. Sarojini Naidu's Select Poems, with an Introduction, Notes, and Bibliography for Further Study. Bareilly: Prakash Book Depot, 1976.

- Keay, John. India: A History. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2000. ISBN 9780871138002.

- Munro-Hay, Stuart. Nakhon Sri Thammarat - The Archaeology, History and Legends of a Southern Thai Town. White Lotus Co Ltd, 2002. ISBN 9747534738 (in English)

- Nagaswamy, R. Introduction Tamil Coins: A Study. Madras: Institute of Epigraphy, 1981. Tamil Arts Academy. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. The Cōlas. (Madras University historical series, no. 9.) Madras: University of Madras, 1955. OCLC 2025491

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. A History of South India from Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar. Madras: Indian Branch, Oxford University Press, 1955. OCLC 1280239

- Puri, Baij Nath. India in Classical Greek Writings. Ahmedabad: New Order Book Co., 1963.

- Sen, Sailendra Nath. Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International, 1999. ISBN 8122411983

External Links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- The Chola Empire.

- Great Living Chola Temples. UNESCO.

| Middle kingdoms of India | ||||||||||||

| Timeline: | Northern Empires | Southern Dynasties | Northwestern Kingdoms | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

6th century B.C.E. |

|

|

(Persian rule)

(Islamic empires) | |||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.