Arabic literature

| History of Literature |

|---|

| The Medieval and Renaissance Periods |

| Matter of Rome |

| Matter of France |

| Matter of Britain |

| Medieval literature |

| Arabic literature |

| 13th century in literature |

| 14th century in literature |

| European Renaissance Literature |

| 15th century in literature |

Arabic literature (Arabic ,الأدب العربي ) Al-Adab Al-Arabi, is the writing produced, both prose and poetry, by speakers (not necessarily native speakers) of the Arabic language. It does not usually include works written using the Arabic alphabet but not in the Arabic language such as Persian literature and Urdu literature. The Arabic word used for literature is adab which is derived from a word meaning "to invite someone for a meal" and implies politeness, culture and enrichment.

Arabic literature emerged in the sixth century with only fragments of the written language appearing before then. It was the Qur'an in the seventh century which would have the greatest lasting effect on Arabic culture and its literature. Arabic literature flourished during the Islamic Golden Age and continues to the present day.

Pre-Islamic literature

- Further information: Pre-Islamic poetry

The period before the writing of the Qur'an and the rise of Islam is known to Muslims as Jahiliyyah or period of ignorance. While this ignorance refers mainly to religious ignorance, there is little written literature before this time, although significant oral tradition is postulated. Tales like those about Sinbad and Antar bin Shaddad were probably current, but were recorded later. The final decades of the sixth century, however, begin to show the flowering of a lively written tradition. This tradition was captured over two centuries later with two important compilations of the Mu'allaqat and the Mufaddaliyat. These collections probably give us a biased picture of the writings of the time as only the best poems are preserved; some of the poems may represent only the best part of a long poem. However they can be stories and novels and even fairy tales as well.

The Qur'an and Islam

The Qur'an had a significant influence on the Arab language. The language used in the Qur'an is called classical Arabic and while modern Arabic has diverged slightly, the classical is still the style to be admired. Not only is the Qur'an the first work of any significant length written in the language it also has a far more complicated structure than the earlier literary works with its 114 suras (chapters) which contain 6,236 ayat (verses). It contains injunctions, narratives, homilies, parables, direct addresses from God, instructions and even comments on itself on how it will be received and understood. It is also, paradoxically, admired for its layers of metaphor as well as its clarity, a feature it mentions itself in sura 16:103.

Although it contains elements of both prose and poetry, and therefore is closest to Saj or rhymed prose, the Qur'an is regarded as entirely apart from these classifications. The text is believed to be divine revelation and is seen by some Muslims as eternal or 'uncreated'. This leads to the doctrine of i'jaz or inimitability of the Qur'an which implies that nobody can copy the work's style nor should anyone try.

This doctrine of i'jaz possibly had a slight limiting effect on Arabic literature; proscribing exactly what could be written. The Qur'an itself criticizes poets in the 26th sura, actually called Ash-Shu'ara or The Poets:

- And as to the poets, those who go astray follow them.

- 16:224

This may have exerted dominance over the pre-Islamic poets of the sixth century whose popularity may have vied with the Qur'an amongst the people. There was a marked lack of significant poets until the 8th century. One notable exception was Hassan ibn Thabit who wrote poems in praise of Muhammad and was known as the "prophet's poet." Just as the Bible has held an important place in the literature of other languages, The Qur'an is important to Arabic. It is the source of many ideas, allusions and quotes and its moral message informs many works.

Aside from the Qur'an the hadith or tradition of what Muhammad is supposed to have said and done are important literature. The entire body of these acts and words are called sunnah or way and the ones regarded as sahih or genuine of them are collected into hadith. Some of the most significant collections of hadith include those by Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj and Muhammad ibn Isma'il al-Bukhari.

The other important genre of work in Qur'anic study is the tafsir or commentaries on the Qur'an. Arab writings relating to religion also includes many sermons and devotional pieces as well as the sayings of Ali which were collected in the tenth century as Nahj al-Balaghah or The Peak of Eloquence.

Islamic scholarship

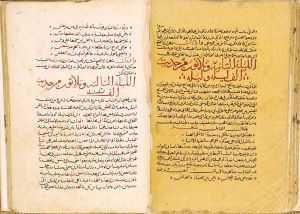

, Ikhwan Alsafa اخوان الصفا)

The research into the life and times of Muhammad, and determining the genuine parts of the sunnah, was an important early reason for scholarship in or about the Arabic language. It was also the reason for the collecting of pre-Islamic poetry; as some of these poets were close to the prophet—Labid actually meeting Muhammad and converting to Islam—and their writings illuminated the times when these event occurred. Muhammad also inspired the first Arabic biographies, known as al-sirah al-nabawiyyah; the earliest was by Wahb ibn Munabbih, but Muhammad ibn Ishaq wrote the best known. While covering the life of the prophet they also told of the battles and events of early Islam and have numerous digressions on older biblical traditions.

Some of the earliest work studying the Arabic language was started in the name of Islam. Tradition has it that the caliph Ali, after reading a Qur'an with errors in it, asked Abu al-Aswad al-Du'ali to write a work codifying Arabic grammar. Khalil ibn Ahmad would later write Kitab al-Ayn, the first dictionary of Arabic, along with works on prosody and music, and his pupil Sibawayh would produce the most respected work of Arabic grammar known simply as al-Kitab or The Book.

Other caliphs exerted their influence on Arabic with 'Abd al-Malik making it the official language for administration of the new empire, and al-Ma'mun setting up the Bayt al-Hikma or House of Wisdom in Baghdad for research and translations. Basrah and Kufah were two other important seats of learning in the early Arab world, between which there was a strong rivalry.

The institutions set up mainly to investigate more fully the Islamic religion were invaluable in studying many other subjects. Caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik was instrumental in enriching the literature by instructing scholars to translate works into Arabic. The first was probably Aristotle's correspondence with Alexander the Great, translated by Salm Abu al-'Ala'. From the east, and in a very different literary genre, Abdullah Ibn al-Muqaffa translated the animal fables of the Panchatantra. These translations would keep alive scholarship and learning, particularly that of ancient Greece, during the dark ages in Europe and the works would often be first re-introduced to Europe from the Arabic versions.

Arabic poetry

A large proportion of Arabic literature before the twentieth century is in the form of poetry, and even prose from this period is either filled with snippets of poetry or is in the form of saj or rhymed prose. The themes of the poetry range from high-flown hymns of praise to bitter personal attacks and from religious and mystical ideas to poems on sex and wine. An important feature of the poetry which would be applied to all of the literature was the idea that it must be pleasing to the ear. The poetry and much of the prose was written with the design that it would be spoken aloud and great care was taken to make all writing as mellifluous as possible. Indeed saj originally meant the cooing of a dove.

Non-fiction literature

Compilations and manuals

In the late ninth century Ibn al-Nadim, a Baghdadi bookseller, compiled a crucial work in the study of Arabic literature. Kitab al-Fihrist is a catalogue of all books available for sale in Baghdad and it gives a fascinating overview of the state of the literature at that time.

One of the most common forms of literature during the Abbasid period was the compilation. These were collections of facts, ideas, instructive stories and poems on a single topic and covers subjects as diverse as house and garden, women, gate-crashers, blind people, envy, animals and misers. These last three compilations were written by al-Jahiz, the acknowledged master of the form. These collections were important for any nadim, a companion to a ruler or noble whose role was often involved regaling the ruler with stories and information to entertain or advise.

A type of work closely allied to the collection was the manual in which writers like ibn Qutaybah offered instruction in subjects like etiquette, how to rule, how to be a bureaucrat and even how to write. Ibn Qutaybah also wrote one of the earliest histories of the Arabs, drawing together biblical stories, Arabic folk tales and more historical events.

The subject of sex was frequently investigated in Arabic literature. The ghazal or love poem had a long history being at times tender and chaste and at other times rather explicit. In the Sufi tradition the love poem would take on a wider, mystical and religious importance. Sex manuals were also written such as The Perfumed Garden, Tawq al-hamamah or The Dove's Neckring by ibn Hazm and Nuzhat al-albab fi-ma la yujad fi kitab or Delight of Hearts Concerning What will Never Be Found in a Book by Ahmad al-Tifashi. Countering such works are one like Rawdat al-muhibbin wa-nuzhat al-mushtaqin or Meadow of Lovers and Diversion of the Infatuated by ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah who advises on how to separate love and lust and avoid sin.

Biography, history, and geography

Aside from the early biographies of Muhammad, the first major biographer to weigh character rather than just producing a hymn of praise was al-Baladhuri with his Kitab ansab al-ashraf or Book of the Genealogies of the Noble, a collection of biographies. Another important biographical dictionary was begun by ibn Khallikan and expanded by al-Safadi and one of the first significant autobiographies was Kitab al-I'tibar which told of Usamah ibn Munqidh and his experiences in fighting in the Crusades.

Ibn Khurdadhbih, apparently an official in the postal service wrote one of the first travel books and the form remained a popular one in Arabic literature with books by ibn Hawqal, ibn Fadlan, al-Istakhri, al-Muqaddasi, al-Idrisi and most famously the travels of ibn Battutah. These give a fascinating view of the many cultures of the wider Islamic world and also offer Muslim perspectives on the non-Muslim peoples on the edges of the empire. They also indicated just how great a trading power the Muslim peoples had become. These were often sprawling accounts that included details of both geography and history.

Some writers concentrated solely on history like al-Ya'qubi and al-Tabari, while others focused on a small portion of history such as ibn al-Azraq, with a history of Mecca, and ibn Abi Tahir Tayfur, writing a history of Baghdad. The historian regarded as the greatest of all Arabic historians though is ibn Khaldun whose history Muqaddimah focuses on society and is a founding text in sociology and economics.

Diaries

In the medieval Near East, Arabic diaries were first being written from before the tenth century, though the medieval diary which most resembles the modern diary was that of Ibn Banna in the eleventh century. His diary was the earliest to be arranged in order of date (ta'rikh in Arabic), very much like modern diaries.[1]

Fiction literature

In the Arab world, there was a great distinction between al-fusha (quality language) and al-ammiyyah (language of the common people). Not many writers would write works in this al-ammiyyah or common language and it was felt that literature had to be improving, educational and with purpose rather than just entertainment. This did not stop the common role of the hakawati or story-teller who would retell the entertaining parts of more educational works or one of the many Arabic fables or folk-tales, which were often not written down in many cases. Nevertheless, some of the earliest novels, including the first philosophical novels, were written by Arabic authors.

Epic literature

The most famous example of Arabic fiction is the The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights), easily the best known of all Arabic literature and which still affects many of the ideas non-Arabs have about Arabic culture. Although regarded as primarily Arabic it was in fact developed from a Persian work and the stories in turn may have their roots in India. A good example of the lack of popular Arabic prose fiction is that the stories of Aladdin and Ali Baba, usually regarded as part of the Tales from One Thousand and One Nights, were not actually part of the Tales. They were first included in French translation of the Tales by Antoine Galland who heard a traditional storyteller recounting some of the tales. They had only existed in incomplete Arabic manuscripts prior to that. The other great character from Arabic literature Sinbad is from the Tales.

The One Thousand and One Nights is usually placed in the genre of Arabic epic literature along with several other works. They are usually, like the Tales, collections of short stories or episodes strung together into a long tale. The extant versions were mostly written down relatively late on, after the fouteenth century, although many were undoubtedly collected earlier and many of the original stories are probably pre-Islamic. Types of stories in these collections include animal fables, proverbs, stories of jihad or propagation of the faith, humorous tales, moral tales, tales about the wily con-man Ali Zaybaq and tales about the prankster Juha.

Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, considered the greatest epic of Italian literature, derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on Islamic eschatology: the Hadith and the Kitab al-Miraj (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before[2] as Liber Scale Machometi, "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder") concerning Muhammad's ascension to Heaven, and the spiritual writings of Ibn Arabi.

Maqama

Maqama, a form of rhymed prose, not only straddles the divide between prose and poetry, but also between fiction and non-fiction. Over a series of short narratives, which are fictionalized versions of real life situations, different ideas are contemplated. A good example of this is a maqama on musk, which purports to compare the feature of different perfumes but is in fact a work of political satire comparing several competing rulers. Maqama also makes use of the doctrine of badi or deliberately adding complexity to display the writer's dexterity with language. Al-Hamadhani is regarded as the originator of the maqama and his work was taken up by Abu Muhammad al-Qasim al-Hariri with one of al-Hariri's maqama a study of al-Hamadhani own work. Maqama was an incredibly popular form of Arabic literature, being one of the few forms which continued to be written during the decline of Arabic in the seventeenth and eighteenth century.

Romantic poetry

A famous example of Arabic poetry on romance (love) is Layla and Majnun, dating back to the Umayyad era in the seventh century. It is a tragic story of undying love much like the later Romeo and Juliet, which was itself said to have been inspired by a Latin version of Layla and Majnun to an extent.[3]

There were several elements of courtly love which were developed in Arabic literature, namely the notions of "love for love's sake" and "exaltation of the beloved lady," which have been traced back to Arabic literature of the ninth and tenth centuries. The notion of the "ennobling power" of love was developed in the early eleventh century by the Persian psychologist and philosopher, Ibn Sina (known as "Avicenna" in Europe), in his Arabic treatise Risala fi'l-Ishq (Treatise on Love). The final element of courtly love, the concept of "love as desire never to be fulfilled," was also at times implicit in Arabic poetry.[4]

Plays

Theater and drama has only been a visible part of Arabic literature in the modern era. There may have been a much longer theatrical tradition but it was probably not regarded as legitimate literature and mostly went unrecorded. There is an ancient tradition of public performance among Shi'i Muslims of a play depicting the life and death of al-Husayn at the battle of Karbala in 680 C.E. There are also several plays composed by Shams al-din Muhammad ibn Daniyal in the thirteenth century when he mentions that older plays are getting stale and offers his new works as fresh material.

The Moors had a noticeable influence on the works of George Peele and William Shakespeare. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's The Battle of Alcazar and Shakespeare's The Merchant of Venice, Titus Andronicus and Othello, which featured a Moorish Othello as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish delegations from Morocco to Elizabethan England at the beginning of the seventeenth century.[5]

Philosophical novels

The Arab Islamic philosophers, Ibn Tufail (Abubacer)[6] and Ibn al-Nafis,[7] were pioneers of the philosophical novel as they wrote the earliest novels dealing with philosophical fiction. Ibn Tufail wrote the first Arabic fictional novel Philosophus Autodidactus as a response to al-Ghazali's The Incoherence of the Philosophers. This was followed by Ibn al-Nafis who wrote a fictional narrative Theologus Autodidactus as a response to Ibn Tufail's Philosophus Autodidactus. Both of these narratives had protagonists (Hayy in Philosophus Autodidactus and Kamil in Theologus Autodidactus) who were autodidactic individuals spontaneously generated in a cave and living in seclusion on a desert island–the earliest examples of a desert island story. However, while Hayy lives alone on the desert island for most of the story in Philosophus Autodidactus (until he meets a castaway named Absal), the story of Kamil extends beyond the desert island setting in Theologus Autodidactus (when castaways take him back to civilization with them), developing into the earliest known coming of age plot and eventually becoming the first example of a science fiction novel.[8][9]

Ibn al-Nafis described his book Theologus Autodidactus as a defense of "the system of Islam and the Muslims' doctrines on the missions of Prophets, the religious laws, the resurrection of the body, and the transitoriness of the world." He presents rational arguments for bodily resurrection and the immortality of the human soul, using both demonstrative reasoning and material from the hadith corpus to prove his case. Later Islamic scholars viewed this work as a response to the metaphysical claim of Avicenna and Ibn Tufail that bodily resurrection cannot be proven through reason, a view that was earlier criticized by al-Ghazali.[10] Ibn al-Nafis' work was later translated into Latin and English as Theologus Autodidactus in the early twentieth century.

A Latin translation of Ibn Tufail's work, entitled Philosophus Autodidactus, first appeared in 1671, prepared by Edward Pococke the Younger. The first English translation by Simon Ockley was published in 1708, and German and Dutch translations were also published at the time. These translations later inspired Daniel Defoe to write Robinson Crusoe, which also featured a desert island narrative and was regarded as the first novel in English. [11][12][13][14] Philosophus Autodidactus also inspired Robert Boyle, an acquaintance of Pococke, to write his own philosophical novel set on an island, The Aspiring Naturalist, in the late seventeenth century.[15] The story also anticipated Rousseau's Émile in some ways, and is also similar to the later story of Mowgli in Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book as well the character of Tarzan, in that a baby is abandoned in a deserted tropical island where he is taken care of and fed by a mother wolf. Other European writers influenced by Philosophus Autodidactus include John Locke,[16] Gottfried Leibniz,[14] Melchisédech Thévenot, John Wallis, Christiaan Huygens,[17] George Keith, Robert Barclay, the Quakers,[18] and Samuel Hartlib.[15]

Science fiction

Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah (The Treatise of Kamil on the Prophet's Biography), known in English as Theologus Autodidactus, written by the Arabian polymath Ibn al-Nafis (1213-1288), is the earliest known science fiction novel. While also being an early desert island story and coming of age story, the novel deals with various science fiction elements such as spontaneous generation, futurology, the end of the world and doomsday, resurrection, and the afterlife. Rather than giving supernatural or mythological explanations for these events, Ibn al-Nafis attempted to explain these plot elements using the scientific knowledge of biology, astronomy, cosmology and geology known in his time. His main purpose behind this science fiction work was to explain Islamic religious teachings in terms of science and philosophy.[19]

Other examples of early Arabic proto-science fiction include the "The City of Brass" and "The Ebony Horse" stories within The Book of One Thousand and One Nights (Arabian Nights),[20] al-Farabi's Opinions of the residents of a splendid city about a utopian society, and al-Qazwini's futuristic tale of Awaj bin 'Unaq about a giant who travelled to Earth from a distant planet.[21]

The decline of Arabic literature

The expansion of the Arab people in the seventh and eighth century brought them into contact with a variety of different peoples who would affect their culture. Most significant for literature was the ancient civilization of Persia. Shu'ubiyya is the name of the conflict between the Arabs and Non-Arabs. Although producing heated debate among scholars and varying styles of literature, this was not a damaging conflict and had more to do with forging a single Islamic cultural identity. Bashshar ibn Burd, of Persian heritage, summed up his own stance in a few lines of poetry:

- Never did he sing camel songs behind a scabby beast,

- nor pierce the bitter colocynth out of sheer hunger

- nor dig a lizard out of the ground and eat it...

The cultural heritage of the desert dwelling Arabs continued to show its influence even though many scholars and writers were living in the large Arab cities. When Khalil ibn Ahmad enumerated the parts of poetry he called the line of verse a bayt or tent and sabah or tent-rope for a foot. Even during the twentieth century this nostalgia for the simple desert life would appear or at least be consciously revived.

A slow resurgence of the Persian language and a re-location of the government and main seat of learning to Baghdad, reduced the production of Arabic literature. Many Arabic themes and styles were taken up in Persian with Omar Khayyam, Attar and Rumi all clearly influenced by the earlier work. The Arabic language still initially retained its importance in politics and administration, although the rise of the Ottoman Empire confined it solely to religion. Alongside Persian, the many variants of the Turkic languages would dominate the literature of the Arab region until the twentieth century. Nevertheless, some Arabic influences remained visible.

Modern literature

| History of modern literature |

|---|

| Modern Asian literature |

|

Arabic literature |

A revival took place in Arabic literature during the nineteenth century along with much of Arabic culture and it is referred to in Arabic as al-Nahda (النهضة), or Renaissance. This resurgence of writing in Arabic was confined mainly to Egypt until the twentieth century when it spread to other countries in the region. This Renaissance was not only felt within the Arab world but also beyond with a great interest in the translating of Arabic works into European languages. Although the use of the Arabic language was revived, many of the tropes of the previous literature which served to make it so ornate and complicated were dropped. Also the western forms of the short story and the novel were preferred over the traditional Arabic forms.

Just as in the eighth century when a movement to translate ancient Greek and other literature helped vitalize Arabic literature, another translation movement would offer new ideas and material for Arabic. An early popular success was The Count of Monte Cristo which spurred a host of historical novels on Arabic subjects. Two important translators were Rifa'ah al -Tahtawi and Jabra Ibrahim Jabra.

Major political change in the region during the mid-twentieth century caused problems for writers. Many suffered censorship and some, such as Sun'allah Ibrahim and Abdul Rahman Munif, were imprisoned. At the same time, others who had written works supporting or praiseworthy of governments were promoted to positions of authority within cultural bodies. Non-fiction writers and academics have also produced political polemics and criticisms aiming to re-shape Arabic politics. Some of the best known are Taha Hussein's The Future of Culture in Egypt which was an important work of Egyptian nationalism and the works of Nawal el-Saadawi who campaigns for women's rights.

Modern Arabic novels

Characteristic of the nahda period of revival were two distinct trends. The Neo-Classical movement sought to rediscover the literary traditions of the past, and was influenced by traditional literary genres such as the maqama and the Thousand and One Nights. In contrast, the Modernist movement began by translating Western works, primarily novels, into Arabic.

Individual authors in Syria, Lebanon, and Egypt created original works by imitating the classical maqama. The most prominent of these was al-Muwaylihi, whose book, The Hadith of Issa ibn Hisham (حديث عيسى بن هشام), critiqued Egyptian society in the period of Ismail. This work constitutes the first stage in the development of the modern Arabic novel. This trend was furthered by Georgy Zeidan, a Lebanese Christian writer who immigrated with his family to Egypt following the Damascus riots of 1860. In the early twentieth century, Zeidan serialized his historical novels in the Egyptian newspaper al-Hilal. These novels were extremely popular because of their clarity of language, simple structure, and the author's vivid imagination. Two other important writers from this period were Khalil Gibran and Mikha'il Na'ima, both of whom incorporated philosophical musings into their works.

Nevertheless, literary critics do not consider the works of these four authors to be true novels, but rather indications of the form that the modern novel would assume. Many of these critics point to Zaynab, a novel by Muhammad Husayn Haykal as the first true Arabic-language novel, while others point to Adraa Denshawi by Muhammad Tahir Haqqi.

A common theme in the modern Arabic novel is the study of family life with obvious resonances with the wider family of the Arabic world. Many of the novels have been unable to avoid the politics and conflicts of the region with war often acting as background to small scale family dramas. The works of Naguib Mahfouz depict life in Cairo, and his Cairo Trilogy, describing the struggles of a modern Cairene family across three generations, won him a Nobel prize for literature in 1988. He was the first Arabic writer to win the prize.

Modern plays

Modern Arabic drama began to be written in the nineteenth century chiefly in Egypt and mainly influenced and in imitation of French works. It was not until the twentieth century that it began to develop a distinctly Arab flavor and be seen elsewhere. The most important Arab playwright was Tawfiq al-Hakim whose first play was a re-telling of the Qur'anic story of the Seven sleepers and the second an epilogue for the Thousand and One Nights. Other important dramatists of the region include Yusuf al'Ani of Iraq and Saadallah Wannous of Syria.

Women in Arabic literature

While not playing a major part in Arabic literature, women have had a continuing role. The earliest poetesses were al-Khansa and Layla al-Akhyaliyyah of the seventh century. Their concentration on the ritha' or elegy suggests that this was a form designated for women to use. A later poetess Walladah, Umawi princess of al-Andulus wrote Sufi poetry and was the lover of fellow poet ibn Zaydun. These and other minor women writers suggest a hidden world of female literature. Women still played an important part as characters in Arabic literature with Sirat al-amirah Dhat al-Himmah an Arabic epic with a female warrior as the chief protagonist and Scheherazade cunningly telling stories in the Thousand and One Nights to save her life.

Modern Arabic literature has allowed a greater number of female writers' works to be published: May Ziade, Fadwa Touqan, Suhayr al-Qalamawi, Ulfat Idlibi, Layla Ba'albakki and Alifa Rifaat are just some of the novelists and short story writers. There has also be a number of significant female academics such as Zaynab al-Ghazali, Nawal el-Saadawi and Fatema Mernissi who among other subject wrote of the place of women in Muslim society. Women writers also courted controversy with Layla Ba'albakki charged with insulting public decency with her short story Spaceships of Tenderness to the Moon.

Literary criticism

Criticism has been inherent in Arabic literature from the start. The poetry festivals of the pre-Islamic period often pitched two poets against each other in a war of verse in which one would be deemed to have won by the audience. The subject adopted a more official status with Islamic study of the Qur'an. Although nothing as crass as literary criticism could be applied to a work which was i'jaz or inimitable and divinely inspired, analysis was permitted. This study allowed for better understanding of the message and facilitated interpretation for practical use, all of which help the development of a critical method important for later work on other literature. A clear distinction regularly drawn between works in literary language and popular works has meant that only part of the literature in Arabic was usually considered worthy of study and criticism.

Some of the first studies of the poetry are Qawa'id al-shi'r or The Rules of Poetry by Tha'lab and Naqd al-shi'r Poetic Criticism by Qudamah ibn Ja'far. Other works tended to continue the tradition of contrasting two poets in order to determine which one best follows the rule of classical poetic structure. Plagiarism also became a significant idea exercising the critcs' concerns. The works of al-Mutanabbi were particularly studied with this concern. He was considered by many the greatest of all Arab poets but his own arrogant self-regard for his abilities did not endear him to other writers and they looked for a source for his verse. Just as there were collections of facts written about many different subjects, numerous collections detailing every possible rhetorical figure used in literature emerged as well as how to write guides.

Modern criticism at first compared the new works unfavorably with the classical ideals of the past but these standards were soon rejected as too artificial. The adoption of the forms of European romantic poetry dictated the introduction of corresponding critical standards. Taha Hussayn, himself keen on European thought, would even dare to challenge the Qur'an with modern critical analysis in which he pointed out the ideas and stories borrowed from pre-Islamic poetry.

Outside views of Arabic literature

Literature in Arabic has been largely unknown outside the Islamic world. Arabic has frequently acted as a time capsule, preserving literature form ancient civilizations to be re-discovered in Renaissance Europe and as a conduit for transmitting literature from distant regions. In this role though it is rarely read but simply re-translated into another standard language like Latin. One of the first important translations of Arabic literature was Robert of Ketton's translation of the Qur'an in the twelfth century but it would not be until the early eighteenth century that much of Arabic's diverse literature would be recognized, largely due to Arabists such as Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot and his books such as Arabic Authors: A Manual of Arabian History and Literature.[22]

Antoine Galland's translation of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights was the first major work in Arabic which found great success outside the Muslim world. Other significant translators were Friedrich Rückert and Richard Burton, along with many working at Fort William, India. The Arabic works and many more in other eastern languages fuelled a fascination in Orientalism within Europe. Works of dubious 'foreign' morals were particularly popular but even these were censored for content, such as homosexual references, which were not permitted in Victorian society. Most of the works chosen for translation helped confirm the stereotypes of the audiences with many more still untranslated. Few modern Arabic works have been translated into other languages.

Noted authors

Poetry

- Ahmad ibn-al-Husayn al-Mutanabbi, (915–965)

- Abu Tammam

- Abu Nuwas, (756–815)

- Al-Khansa(7th century female poet)

- Al-Farazdaq

- Asma bint Marwan

- Jarir ibn Atiyah

- Ibn Zaydun

- Taghribat Bani Hilal forms part of the epic tradition.

- See also: List of Arabic language poets

Prose

Historical

- Antara Ibn Shaddad al-'Absi, pre-Islamic Arab hero and poet (fl. 580 C.E.).

- Muhammad alqasim al-Hariri (1054–1122)

- Al-Jahiz (776–869)

- Muhammad al-Nawaji bin Hasan bin Ali bin Othman, Cairene mystic, Sufi and poet (1383?–1455)

- Ibn Tufail (also a philosopher).

Modern

- Naguib Mahfouz, (1911-2006) Nobel Prize for Literature (1988), famous for the Cairo Trilogy about life in the sprawling inner city

- 'Abbas Mahmud Al-Aqqad, notable Egyptian author and thinker

- Zakaria Tamer, Syrian writer, noted for his short stories

- Tayeb Salih, Sudanese writer

- Abdul Rahman Munif

- Hanna Mina, Syria's foremost novelist

- May Ziadeh, pioneer female writer

- Ahlam Mosteghanemi, notable for being the first Algerian woman published in English

- Hanan al-Shaykh, controversial female Lebanese writer. Author of "The Story of Zahra"

- Ghassan Kanafani, Palestinian writer and political activist

- Elias Khoury, Lebanese novelist

- Sonallah Ibrahim, leftist Egyptian novelist

- Gibran Khalil Gibran, (1883-1931) Lebanese poet and philosopher

Notes

- ↑ Makdisi, George (May 1986), "The Diary in Islamic Historiography: Some Notes", History and Theory 25 (2): 173-185

- ↑ I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet, Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection Lettres Gothiques, (Le Livre de Poche, 1991.) 22 with note 37.

- ↑ NIZAMI: LAYLA AND MAJNUN - English Version by Paul Smith, Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ G. E. von Grunebaum, 1952, "Avicenna's Risâla fî 'l-'išq and Courtly Love," Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 11(4): 233-8 [233-4].

- ↑ Professor Nabil Matar (April 2004), Shakespeare and the Elizabethan Stage Moor, Sam Wanamaker Fellowship Lecture, Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre (cf. Mayor of London (2006), Muslims in London, Greater London Authority.

- ↑ Jon Mcginnis, Classical Arabic Philosophy: An Anthology of Sources, Hackett Publishing Company, ISBN 0872208710. 284

- ↑ Muhsin Mahdi (1974), "The Theologus Autodidactus of Ibn at-Nafis by Max Meyerhof, Joseph Schacht," Journal of the American Oriental Society, 94(2): 232-234.

- ↑ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi, 1982, "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher," Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibn al-Nafis As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World.

- ↑ Nahyan A. G. Fancy, 2006, "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)," 95-101, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame.

- ↑ Nahyan A. G. Fancy, 2006, "Pulmonary Transit and Bodily Resurrection: The Interaction of Medicine, Philosophy and Religion in the Works of Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 1288)," 42, 60, Electronic Theses and Dissertations, University of Notre Dame.

- ↑ Nawal Muhammad Hassan, 1980, Hayy bin Yaqzan and Robinson Crusoe: A study of an early Arabic impact on English literature, Al-Rashid House for Publication.

- ↑ Cyril Glasse, 2001, New Encyclopedia of Islam, 202, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 0759101906.

- ↑ Amber Haque, 2004, "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists," Journal of Religion and Health 43(4): 357-377 [369].

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Martin Wainwright, Desert island scripts, The Guardian, March 22, 2003.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 G. J. Toomer, 1996, Eastern Wisedome and Learning: The Study of Arabic in Seventeenth-Century England, 222, (Oxford University Press, ISBN 0198202911).

- ↑ G. A. Russell, 1994, The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, 224-239, (Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004094598).

- ↑ G. A. Russell, 1994, The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, 227, (Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004094598).

- ↑ G. A. Russell, 1994, The 'Arabick' Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, 247, (Brill Publishers, ISBN 9004094598).

- ↑ Dr. Abu Shadi Al-Roubi, 1982, "Ibn Al-Nafis as a philosopher," Symposium on Ibn al-Nafis, Second International Conference on Islamic Medicine: Islamic Medical Organization, Kuwait (cf. Ibnul-Nafees As a Philosopher, Encyclopedia of Islamic World. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ [http://www.islamscifi.com/?Academic_Literature Academic Literature Islam and Science Fiction] Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ Achmed A. W. Khammas, Science Fiction in Arabic Literature Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- ↑ F.F. Arbuthnot, Arabic Authors: A Manual of Arabian History and Literature, originally published London: William Heinemann (1890). Full text online at project Gutenberg.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, Roger. The Arabic Novel: An Historical and Critical Introduction. Syracuse University Press, 1982. ISBN 0950788503.

- Ashitany, Julia et al. 'Abbasid Belles Lettres. Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521240166

- Badawi, M. M. Modern Arabic Literature Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0521331978

- Badawi, M. M. Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Beeston, A. F. L., T. M. Johnstone, R. B. Serjeant, and G. R. Smith. Arabic Literature to the End of the Umayyad Period Cambridge University Press, 1983. ISBN 0521240158

- El-Enany, Rasheed. Naguib Mahfouz: The Pursuit of Meaning. Routledge, 1993. ISBN 0415073952

- Hashmi, Alamgir. The Worlds of Muslim Imagination. Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, 1986. ISBN 0005004071

- Menocal, María Rosa. The Literature of Al-Andalus. Cambridge University Press, 2000. ISBN 0521471591

- Young, M. J. L. (ed). Religion, Learning and Science in the 'Abbasid Period. Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0521327636

External links

All links retrieved August 11, 2023.

- Arabic Literature Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.