Vagrancy

A vagrant is a person, usually poor, who wanders from place to place without a home or regular work. Urban vagrants are commonly called "street people." Some towns have shelters for vagrants, such as The Rescue Mission in Syracuse, New York.

Vagrancy is a crime in some European countries, but most of these laws have been abandoned. Laws against vagrancy in the United States have largely been invalidated as violative of the due process clauses of the U.S. Constitution. But the FBI report on crime in the United States for 2005 lists 33,227 vagrancy violations. In legal terminology, a person with a source of income is not a vagrant, even if he/she is homeless.

Homelessness refers to the condition and societal category of people who lack fixed housing, usually because they cannot afford a regular, safe, and adequate shelter. The term "homelessness" may also include people whose primary nighttime residence is in a homeless shelter, in an institution that provides a temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized, or in a public or private place not designed for use as a regular sleeping accommodation for human beings. [1][2] A small number of people choose to be homeless nomads, such as some Roma people (Gypsies) and members of some subcultures.

Definition of homeless

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines the term "homeless" or "homeless individual or homeless person" as — (1) an individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence; and (2) an individual who has a primary nighttime residence that is: A) supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations (including welfare hotels, congregate shelters, and transitional housing for the mentally ill); B) an institution that provides a temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized; or C) a public or private place not designed for, or ordinarily used as, a regular sleeping accommodations for human beings.

Other names for homelessness

The term used to describe homeless people in academic articles and government reports is "homeless people." Popular slang terms, some of which are considered derogatory, include: vagrant, tramp, hobo (U.S.), transient, bum (U.S.), bagman/bagwoman, or the wandering poor. The term '(of) No Fixed Abode' (NFA) is used in legal circumstances. Sometimes the term “houseless” is used to reflect a more accurate condition in some cases.[3] [4]

In different languages, the term for homelessness reveals the cultural and societal perception and classification of a homeless person:

- Britain: "rough sleeper" (person who sleeps "in the rough" i.e. outdoors)

- Spanish: "persona sin hogar," (person without a home) , "sin techo" o "sintecho" (person without roof above)

- French: "sans domicile fixe" (SDF, without a fixed domicile)

- German: "obdachlos" (without a shelter)

- Italian: "senzatetto" (without a roof)

- Portuguese: "sem-teto" (without a roof) or "Pessoa sem abrigo" (person without a shelter)

- Polish, Russian, Slovene: "bezdomny," "бездомный," or in more frequent use, "бомж," standing for without fixed place of living (без опрделенного место жительства), "brezdomec" respectively (without a house)

Voluntary homelessness

A small number of homeless people choose to be homeless, living as nomads. "Nomadism has been a way of life in many cultures for thousands of years" either due to the "...seasonal availability of plants and animals" or by "their ability to trade." A 2001 study on homelessness issues in Europe noted that "Urban transience [e.g., homelessness] is different from nomadism/rootlessness or travelling.." in that nomads and Gypsy travellers in caravans have "planned mobility" rather than forced mobility.[5] In Britain, most nomadic people are Roma (or Gypsy) people, Irish travellers, Kalé from North Wales, and Scottish travellers. Many of these people "... continue to maintain a semi-nomadic lifestyle and live in caravans"; however, "others have chosen to settle more permanently in houses." [6]Some European countries have developed policies that acknowledge the unique nomadic (or "travelling") life of Gypsy people[7][8]; similar work has also been done by the Australian government, regarding the subgroup of Aborigine people who are nomadic. In large Japanese cities such as Toyko, the "many manifestations of urban nomadism" include day laborers and subculture groups [9] (e.g., street punks).

Assistance and resources available to the homeless

Refuges for the homeless

There are many places where a homeless person might seek refuge.

- Outdoors: In a sleeping bag, tent, or improvised shelter, such as a large cardboard box, in a park or vacant lot.

- Hobo jungles: Ad hoc campsites of improvised shelters and shacks, usually near rail yards.

- Derelict structures: abandoned or condemned buildings, abandoned cars, and beached boats

- Vehicles: cars or trucks are used as a temporary living refuge, for example those recently evicted from a home. Some people live in vans, covered pick-up trucks, station wagons, or hatchbacks.

- Public places: parks, bus or train stations, airports, public transportation vehicles (by continual riding), hospital lobbies, college campuses, and 24-hour businesses such as coffee shops. Some public places use security guards or police to prevent people from loitering or sleeping at these locations.

- Homeless shelters ranging from official city-run shelter facilities to emergency cold-weather shelters opened by churches or community agencies, which may consist of cots in a heated warehouse.

- Inexpensive Boarding houses called flophouses offer cheap, low-quality temporary lodging.

- Friends or family: Temporarily sleeping in dwellings of friends or family members ("couch surfing"). Couch surfers may be harder to recognize than street homeless people[10]

Health care for the homeless

Health care for the homeless is a major public health challenge, [11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]. Homeless people are more likely to suffer injuries and medical problems from their lifestyle on the street, which includes poor nutrition, substance abuse, exposure to the severe elements of weather, and a higher exposure to violence (robberies, beatings, and so on). Yet at the same time, they have little access to public medical services or clinics, in many cases because they lack health insurance[19] [20] or identification documents. [21] Free-care clinics, especially for the homeless do exist in major cities, but they are usually over-burdened with patients.[22]

The conditions affecting the homeless are somewhat specialized and has opened a new area of medicine catering to this population. Skin diseases and conditions abound, because homeless people are exposed to extreme cold in the winter and they have little access to bathing. Homeless people also have much more severe dental problems than the general population. Specialized medical textbooks have been written to address this for providers.[23]

There are many organizations providing free care all over the world for the homeless, but the services are in great demand given the limited number of medical practitioners helping. For example, it might take months to get a minimal dental appointment in a free-care clinic. Communicable diseases are of great concern, especially tuberculosis, which spreads in the crowded homeless shelters in high density urban settings.

Income Sources

Many non-profit organizations such as Goodwill Industries maintain a mission to "provide skill development and work opportunities to people with barriers to employment," though most of these organizations are not primarily geared toward homeless individuals. Many cities also have street newspapers or magazines: publications designed to provide employment opportunity to homeless people or others in need by street sale.

While some homeless have paying jobs, some must seek other methods to make money. Begging or panhandling is one option, but is becoming increasingly illegal in many cities. Despite the stereotype, not all homeless people panhandle, and not all panhandlers are homeless. Another option is busking: performing tricks, playing music, drawing on the sidewalk, or offering some other form of entertainment in exchange for donations. In cities where pharmaceutical companies still collect paid blood plasma, homeless people may generate income through frequent visits to these centers.

Homeless people have been known to commit crimes just to be sent to jail or prison for food and shelter. In police lingo, this is called "three hots and a cot" referring to the three hot daily meals and a cot to sleep on given to prisoners. Similarly a homeless person may approach a hospital's emergency department and fake a physical or mental illness in order to receive food and shelter.

Main causes of homelessness

The major reasons and causes for homelessness as documented by many reports and studies include:[24][25]

- Lack of affordable housing

- Low paying jobs

- Substance abuse and lack of needed services

- Mental illness and lack of needed services

- Domestic violence

- Unemployment

- Irresponsible life style

- Poverty

- Prison release and re-entry into society

- Change and cuts in public assistance

- Natural Disaster

The high cost of housing is a by-product of the general distribution of wealth and income. The rate of homelessness has also been impacted by the reduction of household size witnessed in the last half of the 20th century.

Individuals who are incapable of maintaining employment and managing their lives effectively due to prolonged and severe drug and/or alcohol abuse make up a substantial percentage of the U.S. homeless population.[26] The link between substance abuse and homelessness is partially caused by the fact that the behavioral patterns associated with addiction can alienate an addicted individual's family and friends who could otherwise provide a safety net against homelessness during difficult economic times.

Increased wealth and income inequality have caused distortions in the housing market that push rent burdens higher, thereby decreasing the availability of affordable housing.

Some homeless individuals choose not to have a permanent residence, including travelers and those who have personal spiritual/religious convictions (as yogis in India). Most researchers feel the population of individuals who choose not to have a permanent residence is negligible. Many people who respond that they "prefer" the homeless lifestyle suffer from mental illness, trauma or have adapted to the lifestyle and the response reflects a socially-desirable response or justification rather than having no real desire for stable shelter.[citation needed]

Pre-disposing factors to homelessness

Most researchers attempt to make a distinction between: 1) why homelessness exists, in general, and 2) who is at-risk of homelessness, in specific. Homelessness has always existed since urbanization and industrialization.

Factors placing an individual at high-risk of homelessness include:

- Poverty: People living in poverty are at a higher risk of becoming homeless.

- Drug or alcohol misuse: It is not uncommon for homeless to suffer from a substance abuse problem. Debate exists about whether drug use is a cause or consequence of homelessness. However, regardless when it arises, an untreated addiction "makes moving beyond homelessness extremely difficult."[27] Substance abuse is quite prevalent in the homeless population.[28]

- Serious Mental Illness and Disability: It has been estimated that approximately one-third of all adult homeless persons have some form of mental illness and/or disability. In previous eras, these individuals were institutionalized in state mental hospitals. According to the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill (NAMI), there were 50,000 mentally ill homeless people in California alone because of deinstitutionalization between 1957 and 1988 and a lack of adequate local service systems.[29] Various assertive outreach approaches, including a mental health treatment approach known as Assertive Community Treatment and the Path Program, have shown promise in the prevention of homelessness among people with serious mental illness.[30][31][32]

- Foster Care background: This population experienced rates of homelessness nearly 8 times higher than the non-foster care population.

- Escaping domestic abuse, including sexual, physical and mental abuse: Victims who flee from abuse often find themselves without a home. Abused children also have a higher chance of succumbing to a drug addiction, which contributes to difficulties in establishing a residence.[33] In 1990 a study found that half of homeless women and children were fleeing abuse.[34]

- Prison discharge: Often the formerly incarcerated are socially isolated from friends and family and have few resources. Employment is often difficult for those with a criminal record. Untreated substance abuse and mental illness also may put them at high risk for homelessness once discharged.[35]

- Civilian during war: Civilians during war or any armed conflict are also are at a higher risk for homelessness, because of possible military attacks on their property, and even after the war rebuilding their homes is often costly, and most commonly the government is overthrown or defeated which is then unable to help its citzens.[36]

Homelessness in specific countries

Statistics for developed countries

The following statistics indicate the approximate average number of homeless people at any one time. Each country has a different approach to counting homeless people, and estimates of homelessness made by different organisations vary wildly, so comparisons should be made with caution.

- European Union: 3,000,000 (UN-HABITAT 2004)

- England: 10,459 rough sleepers, 98,750 households in temporary accommodation (Department for Communities and Local Government 2005)

- Canada: 150,000 (National Homelessness Initiative - Government of Canada)[37]

- Australia: 99,000 (ABS: 2001 Census)[38]

- United States: Chronically homeless people (those with repeated episodes or who have been homeless for long periods) 150,000-200,000 (some sources say 847,000-3,470,000)[39] though a report in January 2006 said 744,000.[40]

- Japan: 20,000-100,000 (some figures put it at 200,000-400,000)[41]

Developing and undeveloped countries

The number of homeless people worldwide has grown steadily in recent years. In some Third World nations such as Brazil, India, Nigeria, and South Africa, homelessness is rampant, with millions of children living and working on the streets. Homelessness has become a problem in the cities of China, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines despite their growing prosperity, mainly due to migrant workers who have trouble finding permanent homes and to rising income inequality between social classes. The Borgen Project estimates that $19 billion a year is needed to end hunger associated with homelessness.

History of homelessness

In the sixteenth century in England, the state first tried to give housing to vagrants instead of punishing them, by introducing bridewells to take vagrants and train them for a profession. In the eighteenth century, these were replaced by workhouses but these were intended to discourage too much reliance on state help. These were later replaced by dormitory housing ("spikes") provided by local boroughs, and these were researched by the writer George Orwell. By the 1930s in England, there were 30,000 people living in these facilities. In the 1960s, the nature and growing problem of homelessness changed for the worse in England, with public concern growing. The number of people living "rough" in the streets had increased dramatically. However, beginning with the Conservative administration's Rough Sleeper Initiative, the number of people sleeping rough in London has fallen from over 1,000 in 1990 to less than 200 in 2006.[citation needed] This initiative was supported further by the incoming Labour administration from 1997 onwards with the publication of the 'Coming in from the Cold' strategy published by the Rough Sleepers Unit, which proposed and delivered a massive increase in the number of hostel bed spaces in the capital and an increase in funding for street outreach teams, who work with rough sleepers to enable them to access services.

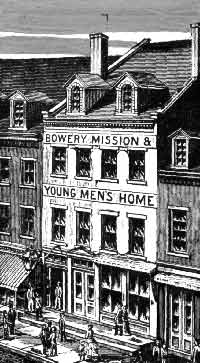

In general, in most countries, many towns and cities had an area which contained the poor, transients, and afflicted, such as a "skid row." In New York City, for example, there was an area known as "The Bowery," traditionally, where alcoholics were to be found sleeping on the streets, bottle in hand. This resulted in rescue missions, such as the oldest homeless shelter in New York City, The Bowery Mission, founded in 1879 by the Rev. and Mrs. A.G. Ruliffson.[42]

In smaller towns, there were hobos, who temporarily lived near train tracks and hopped onto trains to various destinations. Especially following the American Civil War, a large number of homeless men formed part of a counterculture known as "hobohemia" all over America.[43]

Although not specifically about the homeless, Jacob Riis wrote about, documented, and photographed the poor and destitute in New York City tenements in the late 1800s. He wrote a ground-breaking book including such material in "How the Other Half Lives" in 1890, which inspired Jack London's The People of the Abyss (1903). Public awareness was raised by this, causing some changes in building codes and some social conditions.

However, modern homelessness as we know it, started as a result of the economic stresses in society, reduction in the availability of affordable housing, such as SROs, for poorer people. In the United States, in the late 1970s, the deinstitutionalisation of patients from state psychiatric hospitals was a precipitating factor which seeded the homeless population, especially in urban areas such as New York City.[44]

The Community Mental Health Act of 1963 was a pre-disposing factor in setting the stage for homelessness in the United States.[45] Long term psychiatric patients were released from state hospitals into SROs and sent to community health centers for treatment and follow-up. It never quite worked out properly and this population largely was found living in the streets soon thereafter with no sustainable support system.[46][47]

Also, as real estate prices and neighborhood pressure increased to move these people out of their areas, the SROs diminished in number, putting most of their residents in the streets.

Other populations were mixed in later, such as people losing their homes for economic reasons, and those with addictions, the elderly, and others.

Many places where people were once allowed freely to loiter, or purposefully be present, such as churches, public libraries and public atriums, became more strict as the homeless population grew larger and congregated in these places more than ever. As a result, many churches closed their doors when services were not being held, libraries enforced a "no eyes shut" and sometimes a dress policy, and most places hired private security guards to carry out these policies, creating a social tension. Many public toilets were closed.

This banished the homeless population to sidewalks, parks, under bridges, and the like. They also lived in the subway and railroad tunnels in New York City. They seemingly became socially invisible, which was the intention of many of the enforcement policies.

The homeless shelters, which were generally night shelters, made the homeless leave in the morning to whatever they could manage and return in the evening when the beds in the shelters opened up again for sleeping. There were some daytime shelters where the homeless could go, instead of being stranded on the streets, and they could be helped, get counseling, avail themselves of resources, meals, and otherwise spend their day until returning to their overnight sleeping arrangements. An example of such a day center shelter model is Saint Francis House in Boston, Massachusetts, founded in the early 1980s, which opens for the homeless all year long during the daytime hours and was originally based on the settlement house model. [48]

There was also the reality of the "bag" people, the shopping cart people, and the soda can collectors. These people carried around all their possessions with them all the time since they had no place to store them. If they had no access to or capability to get to a shelter and possible bathing, or access to toilets and laundry facilities, their hygiene was lacking. This again created social tensions in public places.

These conditions created an upsurge in tuberculosis and other diseases in urban areas.

In 1979, a New York City lawyer, Robert Hayes, brought a class action suit before the courts, Callahan v. Carey, against the City and State, arguing for a person's state constitutional "right to shelter." It was settled as a consent decree in August 1981. The City and State agreed to provide board and shelter to all homeless men who met the need standard for welfare or who were homeless by certain other standards. By 1983 this right was extended to homeless women.

By the mid-1980s, there was also a dramatic increase in family homelessness. Tied into this was an increasing number of impoverished and runaway children, teenagers, and young adults, which created a new sub-stratum of the homeless population.

Also, in the 1980s, in the United States, some federal legislation was introduced for the homeless as a result of the work of Congressman Stewart B. McKinney. In 1987, the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act was enacted.

Several organisations in some cities, such as New York and Boston, tried to be inventive about help to the swelling number of homeless people. In New York City, for example, in 1989, the first street newspaper was created called "Street News" which put some homeless to work, some writing, producing, and mostly selling the paper on streets and trains.[49] It was written pro bono by a combination of homeless, celebrities, and established writers. In 1991, in England, a street newspaper, following on the New York model was established, called "The Big Issue" and was published weekly.[50] Its circulation grew to 300,000. Chicago has "StreetWise" which has the largest circulation of its kind in the United States, thirty thousand. Boston has a "Spare Change" newspaper built on the same model as the others: homeless helping themselves. More recently, Street Sense, in Washington, D.C. has gained a lot of popularity and helped many make the move out of homelessness. Students in Baltimore, M.D. have opened a satellite office for that street paper as well (www.streetsense.org).

In 2002, research showed that children and families were the largest growing segment of the homeless in America,[51][52] and this has presented new challenges, especially in services, to agencies. Back in the 1990s, a teenager from New York, Liz Murray, was homeless at fifteen years old, and overcame that and went on to study at Harvard University. Her story was made into an Emmy-winning film in 2003, "Homeless to Harvard."

Some trends involving the plight of the homeless have provoked some thought, reflection and debate. One such phenomenon is paid physical advertising, colloquially known as "sandwich board men"[53][54] and another specific type as "Bumvertising." Another trend is the side effect of unpaid free advertising of companies and organisations on shirts, clothing and bags, to be worn by the homeless and poor, given out and donated by companies to homeless shelters and charitable organisations for otherwise altruistic purposes. These trends are reminiscent of the "sandwich board signs" carried by poor people in the time of Charles Dickens in the Victorian 1800s in England[55] and later during the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s.

Violent crimes against the homeless

There have been many violent crimes committed against the homeless. A recent study in 2007 found that this number is increasing. [56] [57]

Homelessness in the popular media

Popular films

- 1966. Cathy Come Home at the Internet Movie Database - An influential film by Ken Loach which raised the profile of homelessness in the UK and led indirectly to the formation of several charities and changes in legislation.

- 1986. Down and Out in Beverly Hills at the Internet Movie Database

- 1991. Life Stinks at the Internet Movie Database

- 1994. With Honors at the Internet Movie Database

- 1997. La Vendedora de Rosas at the Internet Movie Database

- 2003. Homeless to Harvard: the Liz Murray Story at the Internet Movie Database — see Liz Murray

- 2006. The Pursuit of Happyness at the Internet Movie Database - the story of Chris Gardner

Books

- 2005 Without a Net: Middle Class and Homeless (With Kids) in America by Michelle Kennedy

Documentary films

- 1985. Streetwise at the Internet Movie Database — follows homeless Seattle youth.

- 1997. The Street: A Film with the Homeless at the Internet Movie Database — about the Canadian homeless in Montreal. New York Times Review,

- 2000 Dark Days at the Internet Movie Database — A film following the lifes of homeless adults living in the Amtrak tunnels in New York.

- 2001 Children Underground at the Internet Movie Database — Following the lifes of homeless children in Bucharest, Romania.

- 2003. À Margem da Imagem at the Internet Movie Database — about the homeless in São Paulo, Brazil. Its English title is "On the Fringes of São Paulo: Homeless."

- 2004. Homeless in America at the Internet Movie Database

- 2005 Children of Leningradsky at the Internet Movie Database — About homeless children in Moscow.

- 2005 Reversal of Fortune at the Internet Movie Database — Explores what a homeless who is given $100,000 and is free to do with it whatever he wishes.

- 2007 Easy Street — about the homeless in Florida.

TV documentaries

- 1988. Home Sweet Homeless at the Internet Movie Database

Visual Arts

- 2005. Photographic expose by Michel Mersereau entitled "Between The Cracks"

Homeless shelters

Homeless shelters are temporary residences for homeless people. Usually located in urban neighborhoods, they are similar to emergency shelters. The primary difference is that homeless shelters are usually open to anyone, without regard to the reason for need. Some shelters limit their clientele by gender or age.

Most homeless shelters expect clients to stay elsewhere during the day, returning only to sleep, or if the shelter also provides meals, to eat; people in emergency shelters are more likely to stay all day, except for work, school, or errands. Some homeless shelters, however, are open 24 hours a day.

There are daytime-only homeless shelters, where the homeless can go when they cannot stay inside at their night-time sleeping shelter during the day. Such an early model of a daytime homeless shelter providing multi-faceted services is Saint Francis House in Boston, Massachusetts.

Homeless shelters are usually operated by a non-profit agency, a municipal agency, or associated with a church. Many get at least part of their funding from local government entities. Shelters can sometimes be referred to as "human warehouses."

Homeless shelters sometimes also provide other services, such as a soup kitchen, job seeking skills training, job training, job placement, support groups, and/or substance (i.e., drugs and/or alcohol) abuse treatment. If they do not offer any of these services, they can usually refer their clients to agencies that do.

There has been concern about the transmission of diseases in the homeless population housed in shelters, and the people who work there, especially with Tuberculosis. [58]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Office of Applied Studies, United States Department of Health and Human Services,"Terminology"

- ↑ United States Code, Title 42, Chapter 119, Subchapter I, § 11302. United States Code: General definition of a homeless individual.

- ↑ HUD, "Not Homeless-Just Houseless", March 12, 2007.

- ↑ Persall, Steve, "A Focus on the 'houseless'", St. Petersburg Times, February 9, 2007

- ↑ BENCHMARK STUDIESLes formes urbaines de l'errance: lieux, circuits et parcours Florence Bouillon, Gilles Suzanne, Marine Vassort Scientific supervisors: Jean-Samuel Bordreuil and Michel Peraldi LAMES September 2001. Available at: http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:YynUn5ibkj0J:www.feantsa.org/files/national_reports/france/france2003_research_update.pdf+nomadism+homelessness&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=53

- ↑ http://www.connectinghistories.org.uk/Learning%20Packages/Migration/migration_settlement_20c_lp_04.asp

- ↑ Molloy, (1998) Accommodating Nomadism, Belfast: Traveller Movement Northern Ireland Morris, R and Clements, L (2002) At what cost? The economics of Gypsy and Traveller Encampments Bristol: The Policy Press

- ↑ http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:En_4oIBUQwEJ:www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200304/cmselect/cmodpm/633/633we18.htm+nomadism+homelessness&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=49

- ↑ http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:XNKXRa7LHmwJ:www.tradingplaces.org/2001/program.html+nomadism+homelessness&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=7

- ↑ "Homeless advocates urge council to remember 'couch surfers'," Susan O'Neill, Inside Toronto, Canada, 7 July 2006 [1]

- ↑ Aday, Lu Ann [2], "Health status of vulnerable populations," Annual Review of Public Health, 1994;15:487-509. [3]

- ↑ Bibliography on Healthcare for the Homeless [4]

- ↑ United States Department of Health and Human Services, "Healthcare for the Homeless." [5]

- ↑ Ferguson, M., "Shelter for the Homeless," American Journal of Nursing, 1989, pp.1061-2.

- ↑ Lenehan, G., McInnis, B., O'Donnell, and M. Hennessey, "A Nurses' Clinic for the Homeless," American Journal of Nursing, 1985, pp.1237-40.

- ↑ Martin-Ashley, J., "In Celebration of Thirty Years of Caring: Pine Street Inn Nurses Clinic," Unpublished.

- ↑ Homeless Health Concerns - National Library of Medicine

- ↑ Wood, David, (editor), "Delivering Health Care to Homeless Persons: The Diagnosis and Management of Medical and Mental Health Conditions," Springer Publishing Company, March 1992, ISBN 0-8261-7780-8

- ↑ "Each year, millions of people in the United States experience homelessness and are in desperate need of health care services. Most do not have health insurance of any sort, and none have cash to pay for medical care." More information available at: http://www.nhchc.org/Publications/basics_of_homelessness.html

- ↑ "Homeless people's access to appropriate treatment and care is hindered dramatically by a lack of health insurance coverage." Available at: http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:VhB4NFCkd4YJ:www.nationalhomeless.org/health/index.html+homelessness+lack+of+health+care+insurance&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=4

- ↑ "Homeless persons often find it difficult to document their date of birth or their address. Because homeless people usually have no place to store possessions, they often lose their belongings, including their identification and other documents, or find them destroyed by police or others. Without a photo ID, homeless persons cannot get a job or access many social services. They can be denied access to even the most basic assistance: clothing closets, food pantries, certain public benefits, and in some cases, emergency shelters. Obtaining replacement identification is difficult. Without an address, birth certificates cannot be mailed. Fees may be cost-prohibitive for impoverished persons. And some states will not issue birth certificates unless the person has photo identification, creating a Catch-22." Available at: http://72.14.205.104/search?q=cache:ICqOm9_J01cJ:www.nlchp.org/Press/detail.cfm%3FPRID%3D40+homelessness+lack+of+identification+documents&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=2

- ↑

PDF, by Grace Elizabeth Moore, Harvard Divinity School, Center for the Study of World Religions

PDF, by Grace Elizabeth Moore, Harvard Divinity School, Center for the Study of World Religions

- ↑ O'Connell, James, J, M.D., editor, et al. "The Health Care of Homeless Persons: a Manual of Communicable Diseases & Common Problems in Shelters & On the Streets," Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, 2004. [6]

- ↑ United States Conference of Mayors, "A Status Report on Hunger and Homelessness in America's Cities: a 27-city survey," December 2001.

- ↑ United States Conference of Mayors,

PDF, December 2005, "Main Causes of Homelessness," p.63-64.

PDF, December 2005, "Main Causes of Homelessness," p.63-64.  PDF [7]

PDF [7]

- ↑ Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio (2006-09-17). Homelessness: The Causes and Facts. Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- ↑ Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio (2006-09-17). Homelessness: The Causes and Facts. Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- ↑ cf. Booth, Koegel, et al. "Vulnerability Factors for Homelessness Associated with Substance Dependence in a Community Sample of Homeless Adults," 2002.

- ↑ http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/content/full/hlthaff.w5.212/DC1

- ↑ Robert A. Rosenheck, MD; Deborah Dennis, MA, "Time-Limited Assertive Community Treatment for Homeless Persons With Severe Mental Illness," Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:1073-1080. [8]

- ↑ Dixon L, Weiden P, Torres M, Lehman A., "Assertive community treatment and medication compliance in the homeless mentally ill," American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997 Sep;154(9):1302-4. [9]

- ↑ Meisler N, Blankertz L, Santos AB, McKay C., "Impact of assertive community treatment on homeless persons with co-occurring severe psychiatric and substance use disorders," Community Mental Health Journal, 1997 Apr;33(2):113-22. [10]

- ↑ Homeless Agency. Facts about Homelessness: Causes of Homelessness. Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- ↑ National Coalition for the Homeless (June 2005). Often, more local resources are available to fleeing women and children as this group is easier to identify and improve their situation.

PDF. Retrieved 2006-05-11.

PDF. Retrieved 2006-05-11.

- ↑ Chicago Coalition for the Homeless. Homelessness—Causes and Facts. Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- ↑

PDF

PDF

- ↑ Government of Canada, "National Homelessness Initiative: Working Together"

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics, "Housing Arrangements: Homelessness," 2004. [11]

- ↑ [12]National Alliance to End Homelessness

- ↑ "Study: 744,000 homeless people in U.S.". Associated Press. 10 January 2006. Article is here, too.

- ↑ "In pictures: Japan's homeless," BBC News.

- ↑ The Bowery Mission [13] For a history see [14]

- ↑ Depastino, Todd, "Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America" [15]

- ↑ Scherl D.J., Macht L.B., "Deinstitutionalization in the absence of consensus," Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 1979 Sep;30(9):599-604 [16]

- ↑ Rochefort, D.A., "Origins of the 'Third psychiatric revolution': the Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963," Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 1984 Spring;9(1):1-30. [17]

- ↑ Feldman, S., "Out of the hospital, onto the streets: the overselling of benevolence," Hastings Center Report, 1983 Jun;13(3):5-7. [18]

- ↑ Borus J.F., "Sounding Board. Deinstitutionalization of the chronically mentally ill," New England Journal of Medicine, 1981 6 August;305(6):339-42. [19]

- ↑ Keane, Thomas, Jr., "Greiff's activism isn't just a good act", Friday, July 4, 2003

- ↑ Harman, Dana, "Read all about it: street papers flourish across the US," The Christian Science Monitor, November 17, 2003. [20]

- ↑ http://www.bigissue.com/

- ↑ FACS, "Homeless Children, Poverty, Faith and Community: Understanding and Reporting the Local Story," March 26 2002 Akron, Ohio. [21]

- ↑ National Coalition for the Homeless, "Homeless Youth" 2005

PDF

PDF

- ↑ Schreiber Cindy, "Sandwich men bring in the bread and butter," Columbia (University) News Service, May 8 2002. [22]

- ↑ Associated Press and CNN, "Pizza company hires homeless to hold ads," Tuesday, June 17 2003. [23]

- ↑ Victorian London site, "Sandwich Men" [24]

- ↑ Lewan, Todd, "Unprovoked Beatings of Homeless Soaring", Associated Press, April 8, 2007.

- ↑ National Coalition for the Homeless, Hate, "Violence, and Death on Main Street USA: A report on Hate Crimes and Violence Against People Experiencing Homelessness, 2006", February 2007.

- ↑ "Occupational Exposure to Tuberculosis" - OSHA notice, 1997.

Bibliography

- Baumohl, Jim [25], (editor), "Homelessness in America," Oryx Press, Phoenix, 1996.

- BBC News, "Warning over homelessness figures: Government claims that homelessness numbers have fallen by a fifth since last year should be taken with a health warning, says housing charity Shelter", Monday, 13 June 2005.

- BBC Radio 4, "No Home, a season of television and radio programmes that introduce the new homeless.", 2006.

- Booth, Brenda M., Sullivan, J. Greer, Koegel, Paul, Burnam, M. Audrey, "Vulnerability Factors for Homelessness Associated with Substance Dependence in a Community Sample of Homeless Adults", RAND Research Report. Originally published in: American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, v. 28, no. 3, 2002, pp. 429-452.

- Charlton, Emma, "France to create 'legal right' to housing", Agence France-Presse news, January 3 2006.

- Coalition for the Homeless (New York), "A History of Modern Homelessness in New York City."

PDF

PDF - Cooper, Yvette, MP, "Effective Homelessness Prevention", April 12 2006.

- Crimaldi, Laura,"Homeless getting new lease on life," Boston Herald, December 11 2006

- Culhane, Dennis [26], "Responding to Homelessness: Policies and Politics," 2001. [27]

- deMause, Neil, "Out of the Shelter, Into the Fire: New city program for homeless: Keep your job or keep your apartment," The Village Voice, New York, June 20 2006. [28]

- DePastino, Todd, "Citizen Hobo: How a Century of Homelessness Shaped America," 2003. ISBN 0-226-14378-3

- Duffy, Gary, "Brazil's homeless and landless unite", BBC News, Sao Paulo, April 17, 2007.

- Institute for Governmental Studies, Berkeley, "Urban Homelessness & Public Policy Solutions: A One-Day Conference," January 22 2001[29]

- Kahn, Ric,"Buried in Obscurity", Boston Globe, December 17 2006.

- Kusmer, Kenneth L. [30], "Down and Out, On the Road: The Homeless in American History," Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-19-504778-8

- Morton, Margaret, "The Tunnel: The Underground Homeless Of New York City," Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-300-06559-0

- Riis, Jacob, "How the Other Half Lives," 1890. [31]

- Rossi, Peter H., "Down and Out in America: The Origins of Homelessness," University Of Chicago Press, 1990.

- Schutt, Russell K., Ph.D., Professor, University of Massachusetts Boston.

- Schutt, Russell K., et al., "Boston's Homeless, 1986-87: Change and Continuity", 1987.

- Schutt, Russell K., Working with the Homeless: the Backgrounds, Activities and Beliefs of Shelter Staff, 1988.

- Schutt, Russell, K., "Homeless Adults in Boston in 1990: A Two-Shelter Profile", 1990.

- Schutt, Russell K., Garrett, Gerald R., "Responding to the Homeless: Policy and Practice", Topics in Social Psychiatry, 1992. ISBN 0-306-44076-8

- Schutt, Russell K., Byrne, Francine, et al., "City of Boston Homeless Services: Employment & Training for Homeless Persons", 1995.

- Schutt, Russell K., Feldman, James, et al., "Homeless Persons’ Residential Preferences and Needs: A Pilot Survey of Persons with Severe Mental Illness in Boston Mental Health and Generic Shelters", 2004.

- Sommer, Heidi, "Homelessness in Urban America: a Review of the Literature," 2001.

PDF

PDF - St. Mungo's organisation (UK), "A Brief History of Homelessness." [32]

- Sweeney, Richard.,"Out of Place: Homelessness in America," HarperCollins College Publishers, 1992.

- Vissing, Yvonne [33], "Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Homeless Children and Families in Small-Town America," 1996.

- Vissing, Yvonne, "The $ubtle War Against Children," Fellowship, March/April 2003. [34]

- Vladeck, Bruce, R., and the Committee on Health Care for Homeless People, Institute of Medicine, "Homelessness, Health, and Human needs," National Academies Press, 1988. [35]

- Toth, Jennifer, "The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City," 1993. ISBN 1-55652-190-1

- United States Conference of Mayors, "Hunger and Homelessness Survery," December 2005.

PDF [36]

PDF [36]

External links

- The Borgen Project

- Homeless Statistics

- Salvation Army

- David Shankbone's "Street Sleepers" photograph series

- Les Enfants de Don Quichotte, French NGO which organized illegal camping-sites on the Canal Saint-Martin in Paris end of December 2006-January 2007 in order to enforce the right to lodging (droit au logement).

- Toxic Playground: Growing Up In Skid Row

- Interview with a young Japanese homeless man

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.