Nanna

m (→Background) |

|||

| (48 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Khashkhamer seal moon worship.jpg|thumb| | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | + | {{epname|Nanna}} | |

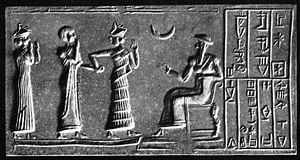

| + | [[Image:Khashkhamer seal moon worship.jpg|thumb|300px|Impression of the cylinder seal of Ḫašḫamer, a high priest of Sîn, ca. 2100 B.C.E. The seated figure is probably King [[Ur-Nammu]], who dedicated the great [[ziggurat]] of [[Ur]] in honor of Nanna/Sîn, who is present in the form of the crescent.]] | ||

| − | + | '''Nanna,''' also called '''Sîn''' (or '''Suen''') was a [[Sumer]]ian [[god]] who played a longstanding role in [[Mesopotamian religion]] and [[mythology]]. He was the [[lunar deity|god of the moon]], the son of the sky god [[Enlil]] and the grain goddess [[Ninlil]]. His sacred city was [[Ur]], and temples dedicated to him have been found throughout [[Mesopotamia]]. The daughters of Mesopotamian kings were often assigned to be his high priestess. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The worship of Nanna was associated with the breeding of cattle, which was a key part of the economy of the lower Euphrates valley. Known as Nanna in [[Sumer]], he was named '''Sîn''' (contracted from ''Su-en'') in the later civilizations of [[Babylonia]] and [[Assyria]], where he had a major temple in [[Harran]]. His wife was the reed goddess [[Ningal]] ("Great Lady"), who bore him [[Shamash]] (Sumerian: Utu, "Sun") and [[Ishtar]] ([[Inanna]]), the goddess of love and war. In later centuries, he became part of an astral triad consisting of himself and his two great children, representing the positions of sun and [[morning star]] ([[Venus]]). In art, his symbols are the crescent moon, the [[bull]], and the [[tripod]]. In his anthropomorphized form, Sîn had a beard made of [[lapis lazuli]] and rode on a winged [[Cattle|bull]]. | |

| − | "The | + | ==Mythology== |

| + | [[Image:Ninhursag1.jpg|thumb|left|Nanna's parents, [[Enlil]] and [[Ninlil]]]] | ||

| + | In Mesopotamian mythology, Nanna was the son of the sky god [[Enlil]] and and the grain goddess [[Ninlil]]. Nanna's origin myth is a story of his father's passion and his mother's sacrificial love. The [[virgin]] Ninlil bathes in the sacred river, where she is seen by the "bright eye" of Enlil, who falls in love with her and seduces (or rapes) her. The assembly of the gods then banishes Enlil to the [[underworld]] for this transgression. Ninlil, knowing she is pregnant with the "bright seed of Sîn," follows Enlil to the world of the dead, determined that "my master's seed can go up to the heavens!" Once the moon god is born in the underworld, three additional deities are born to his parents, allowing Nanna/Suen to take his place in the skies to light up the night. Nanna's own best-known offspring were the sun god [[Shamash]] and the great goddess of love and war, [[Inanna]], better known today as [[Ishtar]]. | ||

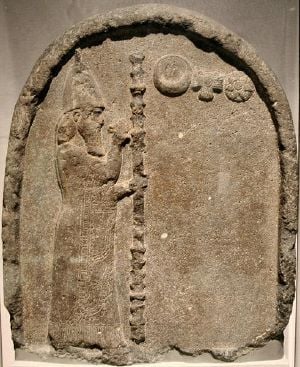

| − | + | [[Image:Kudurru Melishipak Louvre Sb23.jpg|thumb|200px|King Melishipak I (1186–1172 B.C.E.) presents his daughter. The crescent moon represents Sîn, while the sun and star represent [[Shamash]] and [[Ishtar]].]] | |

| + | |||

| + | The moon played a key role in Mesopotamian religious culture. As it moved through its phases, people learned to keep their calendars based on the lunar month. Nanna (or Suen/Sîn) was sometimes pictured as riding his crescent moon-boat as it made its monthly journey through the skies. Some sources indicate that the moon god was called by different names according to various phases of the moon. ''Sîn'' was especially associated with the crescent moon, while the older Sumerian name Nanna was connected either to the full or the new moon. The horns of a bull were also sometimes equated with the moon's crescent. | ||

| − | + | People speculated that perhaps the crescent moon-disk was Nanna's crown, and thus one of his titles was "Lord of the Diadem." As the mysterious [[deity]] of the night, he was also called "He whose deep heart no god can penetrate." His chief attribute, however, was [[wisdom]], which he dispensed not only to humans through his priests, but also to the gods themselves who came to consult him every month. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Sîn's status was very formidable, not only in terms of the temples dedicated to him, but also in terms of [[astrology]], which became a prominent feature of later [[Mesopotamian religion]], and even legal matters. For an entire millennium—from 1900 to 900 B.C.E.—Sîn's name is invoked as a witness to international treaties and covenants made by the Babylonian kings. His attribute of [[wisdom]] was particularly expressed in the [[science]] of astrology, in which the observation of the moon's phases was an important factor. The centralizing tendency in Mesopotamian religion led to his incorporation in the divine triad consisting of Sîn, [[Shamash]], and [[Ishtar]], respectively personifying the [[moon]], the [[sun]], and the planet [[Venus]]. In this trinity, the moon held the central position. However, it is likely that Ishtar came to play the more important cultural role as time went on, as she rose to the key position among the Mesopotamian goddesses, while younger deities like [[Marduk]] came to predominate on the male side of the [[pantheon]]. | |

| − | + | ==Worship and influence== | |

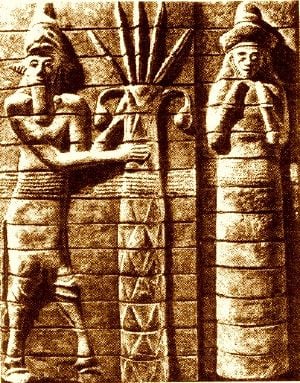

| − | + | [[Image:Nabonidus-moon.jpg|thumb|left|Nabonidus (sixth century B.C.E.) venerates the triad of Sin, [[Shamash]], and [[Ishtar]].]] | |

| − | the so-called "giparu" ( | + | The two chief seats of Sîn's worship were [[Ur]] in the south, and later [[Harran]] to the north. The so-called "giparu" (Sumerian: Gig-Par-Ku) at Ur, where Nanna's priestesses resided, was a major complex with multiple courtyards, a number of sanctuaries, burial chambers for dead priestesses, a ceremonial banquet hall, and other structures. From about 2600-2400 B.C.E.), when Ur was the leading city of the [[Euphrates]] valley, Sîn seems to have held the position of the head of the [[Pantheon (gods)|pantheon]]. It was during this period that he inherited such titles as "Father of the Gods," "Chief of the Gods," and "Creator of All Things," which were assigned to other deities in other periods. |

| − | + | The [[cult]] of Sîn spread to other centers, and temples of the moon god have been found in all the large cities of [[Babylonia]] and [[Assyria]]. Sîn's chief sanctuary at Ur was named ''E-gish-shir-gal'' ("house of the great light"). In spring, a procession from Ur, led by the priests of Nanna/Sîn, made a ritual journey, to [[Nippur]], the city of [[Enlil]], bringing the year's first dairy products. Sîn's sanctuary at [[Harran]] was named ''E-khul-khul'' ("house of joys"). [[Inanna]]/[[Ishtar]] often played an important role in these temples as well. | |

| − | + | On [[cylinder seal]]s, Sîn is represented as an old man with a flowing [[beard]], with the crescent as his symbol. In the later astral-theological system he is represented by the number 30 and the moon, often in crescent form. This number probably refers to the average number of days in a [[lunation|lunar month]], as measured between successive [[new moon]]s. Writings often refer to him as ''En-zu,'' meaning "Lord of Wisdom." | |

| − | |||

| − | + | One of Nanna/Sîn's most famous worshipers was [[Enheduanna]], his high priestess who lived in the twenty-third century B.C.E.. and is known today as the first named author in history, as well as the first to write in the [[first person]]. The daughter of King [[Sargon I]], her writings invoke [[Inanna]]'s aid as Sîn's daughter, far more than they dare to speak to the god directly. After Enheduanna, a long tradition continued whereby kings appointed their daughters as high priestesses of Sîn, as a means of solidifying their power. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Ancient ziggurat at Ali Air Base Iraq 2005.jpg|thumb|250px|The great [[ziggurat]] of [[Ur]].]] | |

| − | + | The great [[ziggurat]] of [[Ur]] was dedicated to Nanna and Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur (in present-day southern Iraq) in the twenty-first century B.C.E. A huge stepped platform, in Sumerian times it was called ''E-temen-nigur.'' Today, after more than 4,000 years, the ziggurat is still well preserved in large parts and has been partially reconstructed. Its upper stage is over 100 feet (30 m) high and the base is 210 feet (64 m) by 150 feet (46 m). | |

| − | + | The ziggurat was only part of the temple complex, which was Nanna's dwelling place as the patron [[deity]] of Ur. The ziggurat served to bridge the distance between the sky and the earth, and it—or another like it—served as the basis for the famous story of the [[Tower of Babel]] in the [[Bible]]. It later fell into disrepair but was restored by the Assyrian King [[Shalmaneser]] in the ninth century B.C.E.., and once again by [[Ashurbanipal]] in the seventh century B.C.E.. | |

| − | + | About 550 B.C.E., [[Nabonidus]], the last of the neo-Babylonian kings, showed particular devotion to Sîn. His mother had been Sîn's high priestess at [[Harran]], and he placed his daughter in the same position at Ur. Some scholars believe that Nabonidus promoted Sîn as the national god of Babylon, superior even to [[Marduk]], who had been promoted to the king of the gods since the time of [[Hammurabi]]. The inscription from one of Nabonidus' cylinders typifies his piety: | |

| − | + | [[Image:Weight Shulgi Louvre AO22187.jpg|thumb|Measuring weight with the symbol of Nanna used by his priests at Ur and dedicated by King Shulgi in the twenty-first century B.C.E..]] | |

| − | + | <blockquote>O Sîn, King of the Gods of Heaven and the Netherworld, without whom no city or country can be founded, nor be restored, when you enter (your temple) E-khul-khul, the dwelling of your plenitude, may good recommendations for that city and that temple be set on your lips. May the gods who dwell in heaven and the netherworld constantly praise the temple of E-khul-khul, the father, their creator. As for me, Nabonidus, King of Babylon, who completed that temple, may Sîn, King of the Gods of Heaven and the Netherworld, joyfully cast his favorable look upon me and every month, in rising and setting, make my ominous signs favorable.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | In any case, Nabodinus' support for the temples of Sîn seems to have alienated the priests at the capital of Babylon, who were devoted to [[Marduk]] and consequently denigrated Nabonidus for his lack of attention to his religious duties in the capital. They later welcomed [[Cyrus the Great]] of Persia when he overthrew Nabonidus. | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Legacy=== | ||

| + | After this, Sîn continued to play a role in [[Mesopotamian]] religion, but a waning one. In [[Canannite mythology]], he was known as Yarikh. His daughter [[Ishtar]], meanwhile, came to play a major role among the [[Canaan]]ites as [[Astarte]]. The Hebrew patriarch [[Abraham]] had connections both to Ur and Harran, where he certainly must have encountered the moon god as a major presence. His descendants, the [[Israelites]], rejected all deities but [[Yawheh]], but they apparently retained the [[new moon]] festivals of their Mesopotamian ancestors. Numbers 10:10 thus instructs that: "At your times of rejoicing—your appointed feasts and New Moon festivals—you are to sound the trumpets over your burnt offerings and fellowship offerings, and they will be a memorial for you before your God." Christian writers have sometimes seen a connection between Sîn and the Muslim god [[Allah]], noting that before his conversion to [[Islam]], [[Muhammad]] himself worshiped several deities, including the moon, and that Islam adopted Nanna's crescent as its symbol. | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Mesopotamian religion]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Ishtar]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Nabonidus]] |

==References== | ==References== | ||

| + | * Black, Jeremy A., Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, and Gabor Zolyomi (eds.). ''The literature of ancient Sumer''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780199296330. | ||

| + | * Finkel, Irving L., and Markham J. Geller. ''Sumerian Gods and Their Representations''. Cuneiform monographs, 7. Groningen: STYX Publications, 1997. ISBN 9789056930059. | ||

| + | * Green, Tamara M. ''The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran''. E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1992. ISBN 9004095136. | ||

| + | * Lambert, W. G. ''The Historical Development of the Mesopotamian Pantheon: A Study in Sophisticated Polytheism''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. {{OCLC|270102751}} | ||

| + | |||

*{{1911}} | *{{1911}} | ||

| − | + | [[category:Philosophy and religion]] | |

| + | [[category:religion]] | ||

| + | [[category:history]] | ||

| + | [[category:History of the Middle East]] | ||

| + | [[Category:mythology]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|236182159}} | {{credit|236182159}} | ||

Latest revision as of 08:45, 9 October 2022

Nanna, also called Sîn (or Suen) was a Sumerian god who played a longstanding role in Mesopotamian religion and mythology. He was the god of the moon, the son of the sky god Enlil and the grain goddess Ninlil. His sacred city was Ur, and temples dedicated to him have been found throughout Mesopotamia. The daughters of Mesopotamian kings were often assigned to be his high priestess.

The worship of Nanna was associated with the breeding of cattle, which was a key part of the economy of the lower Euphrates valley. Known as Nanna in Sumer, he was named Sîn (contracted from Su-en) in the later civilizations of Babylonia and Assyria, where he had a major temple in Harran. His wife was the reed goddess Ningal ("Great Lady"), who bore him Shamash (Sumerian: Utu, "Sun") and Ishtar (Inanna), the goddess of love and war. In later centuries, he became part of an astral triad consisting of himself and his two great children, representing the positions of sun and morning star (Venus). In art, his symbols are the crescent moon, the bull, and the tripod. In his anthropomorphized form, Sîn had a beard made of lapis lazuli and rode on a winged bull.

Mythology

In Mesopotamian mythology, Nanna was the son of the sky god Enlil and and the grain goddess Ninlil. Nanna's origin myth is a story of his father's passion and his mother's sacrificial love. The virgin Ninlil bathes in the sacred river, where she is seen by the "bright eye" of Enlil, who falls in love with her and seduces (or rapes) her. The assembly of the gods then banishes Enlil to the underworld for this transgression. Ninlil, knowing she is pregnant with the "bright seed of Sîn," follows Enlil to the world of the dead, determined that "my master's seed can go up to the heavens!" Once the moon god is born in the underworld, three additional deities are born to his parents, allowing Nanna/Suen to take his place in the skies to light up the night. Nanna's own best-known offspring were the sun god Shamash and the great goddess of love and war, Inanna, better known today as Ishtar.

The moon played a key role in Mesopotamian religious culture. As it moved through its phases, people learned to keep their calendars based on the lunar month. Nanna (or Suen/Sîn) was sometimes pictured as riding his crescent moon-boat as it made its monthly journey through the skies. Some sources indicate that the moon god was called by different names according to various phases of the moon. Sîn was especially associated with the crescent moon, while the older Sumerian name Nanna was connected either to the full or the new moon. The horns of a bull were also sometimes equated with the moon's crescent.

People speculated that perhaps the crescent moon-disk was Nanna's crown, and thus one of his titles was "Lord of the Diadem." As the mysterious deity of the night, he was also called "He whose deep heart no god can penetrate." His chief attribute, however, was wisdom, which he dispensed not only to humans through his priests, but also to the gods themselves who came to consult him every month.

Sîn's status was very formidable, not only in terms of the temples dedicated to him, but also in terms of astrology, which became a prominent feature of later Mesopotamian religion, and even legal matters. For an entire millennium—from 1900 to 900 B.C.E.—Sîn's name is invoked as a witness to international treaties and covenants made by the Babylonian kings. His attribute of wisdom was particularly expressed in the science of astrology, in which the observation of the moon's phases was an important factor. The centralizing tendency in Mesopotamian religion led to his incorporation in the divine triad consisting of Sîn, Shamash, and Ishtar, respectively personifying the moon, the sun, and the planet Venus. In this trinity, the moon held the central position. However, it is likely that Ishtar came to play the more important cultural role as time went on, as she rose to the key position among the Mesopotamian goddesses, while younger deities like Marduk came to predominate on the male side of the pantheon.

Worship and influence

The two chief seats of Sîn's worship were Ur in the south, and later Harran to the north. The so-called "giparu" (Sumerian: Gig-Par-Ku) at Ur, where Nanna's priestesses resided, was a major complex with multiple courtyards, a number of sanctuaries, burial chambers for dead priestesses, a ceremonial banquet hall, and other structures. From about 2600-2400 B.C.E.), when Ur was the leading city of the Euphrates valley, Sîn seems to have held the position of the head of the pantheon. It was during this period that he inherited such titles as "Father of the Gods," "Chief of the Gods," and "Creator of All Things," which were assigned to other deities in other periods.

The cult of Sîn spread to other centers, and temples of the moon god have been found in all the large cities of Babylonia and Assyria. Sîn's chief sanctuary at Ur was named E-gish-shir-gal ("house of the great light"). In spring, a procession from Ur, led by the priests of Nanna/Sîn, made a ritual journey, to Nippur, the city of Enlil, bringing the year's first dairy products. Sîn's sanctuary at Harran was named E-khul-khul ("house of joys"). Inanna/Ishtar often played an important role in these temples as well.

On cylinder seals, Sîn is represented as an old man with a flowing beard, with the crescent as his symbol. In the later astral-theological system he is represented by the number 30 and the moon, often in crescent form. This number probably refers to the average number of days in a lunar month, as measured between successive new moons. Writings often refer to him as En-zu, meaning "Lord of Wisdom."

One of Nanna/Sîn's most famous worshipers was Enheduanna, his high priestess who lived in the twenty-third century B.C.E. and is known today as the first named author in history, as well as the first to write in the first person. The daughter of King Sargon I, her writings invoke Inanna's aid as Sîn's daughter, far more than they dare to speak to the god directly. After Enheduanna, a long tradition continued whereby kings appointed their daughters as high priestesses of Sîn, as a means of solidifying their power.

The great ziggurat of Ur was dedicated to Nanna and Inanna in the Sumerian city of Ur (in present-day southern Iraq) in the twenty-first century B.C.E. A huge stepped platform, in Sumerian times it was called E-temen-nigur. Today, after more than 4,000 years, the ziggurat is still well preserved in large parts and has been partially reconstructed. Its upper stage is over 100 feet (30 m) high and the base is 210 feet (64 m) by 150 feet (46 m).

The ziggurat was only part of the temple complex, which was Nanna's dwelling place as the patron deity of Ur. The ziggurat served to bridge the distance between the sky and the earth, and it—or another like it—served as the basis for the famous story of the Tower of Babel in the Bible. It later fell into disrepair but was restored by the Assyrian King Shalmaneser in the ninth century B.C.E., and once again by Ashurbanipal in the seventh century B.C.E.

About 550 B.C.E., Nabonidus, the last of the neo-Babylonian kings, showed particular devotion to Sîn. His mother had been Sîn's high priestess at Harran, and he placed his daughter in the same position at Ur. Some scholars believe that Nabonidus promoted Sîn as the national god of Babylon, superior even to Marduk, who had been promoted to the king of the gods since the time of Hammurabi. The inscription from one of Nabonidus' cylinders typifies his piety:

O Sîn, King of the Gods of Heaven and the Netherworld, without whom no city or country can be founded, nor be restored, when you enter (your temple) E-khul-khul, the dwelling of your plenitude, may good recommendations for that city and that temple be set on your lips. May the gods who dwell in heaven and the netherworld constantly praise the temple of E-khul-khul, the father, their creator. As for me, Nabonidus, King of Babylon, who completed that temple, may Sîn, King of the Gods of Heaven and the Netherworld, joyfully cast his favorable look upon me and every month, in rising and setting, make my ominous signs favorable.

In any case, Nabodinus' support for the temples of Sîn seems to have alienated the priests at the capital of Babylon, who were devoted to Marduk and consequently denigrated Nabonidus for his lack of attention to his religious duties in the capital. They later welcomed Cyrus the Great of Persia when he overthrew Nabonidus.

Legacy

After this, Sîn continued to play a role in Mesopotamian religion, but a waning one. In Canannite mythology, he was known as Yarikh. His daughter Ishtar, meanwhile, came to play a major role among the Canaanites as Astarte. The Hebrew patriarch Abraham had connections both to Ur and Harran, where he certainly must have encountered the moon god as a major presence. His descendants, the Israelites, rejected all deities but Yawheh, but they apparently retained the new moon festivals of their Mesopotamian ancestors. Numbers 10:10 thus instructs that: "At your times of rejoicing—your appointed feasts and New Moon festivals—you are to sound the trumpets over your burnt offerings and fellowship offerings, and they will be a memorial for you before your God." Christian writers have sometimes seen a connection between Sîn and the Muslim god Allah, noting that before his conversion to Islam, Muhammad himself worshiped several deities, including the moon, and that Islam adopted Nanna's crescent as its symbol.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Black, Jeremy A., Graham Cunningham, Eleanor Robson, and Gabor Zolyomi (eds.). The literature of ancient Sumer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780199296330.

- Finkel, Irving L., and Markham J. Geller. Sumerian Gods and Their Representations. Cuneiform monographs, 7. Groningen: STYX Publications, 1997. ISBN 9789056930059.

- Green, Tamara M. The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran. E.J. Brill, Leiden, 1992. ISBN 9004095136.

- Lambert, W. G. The Historical Development of the Mesopotamian Pantheon: A Study in Sophisticated Polytheism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975. OCLC 270102751

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.