Hooke, Robert

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) (→Career) |

(→Career) |

||

| (35 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Hooke, Robert}} |

| + | [[File:Inscription-to-Hooke-in-Westminster-Abbey.jpg|thumb|350px|Hooke memorial floor tile in [[Westminster Abbey]]]] | ||

| − | '''Robert Hooke''' | + | '''Robert Hooke''' (July 18, 1635 – March 3, 1703) was an [[England|English]] [[polymath]], a scientist, [[mathematics|mathematician]], and [[architecture|architect]], who played an important role in the scientific revolution, through both experimental and theoretical work. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Hooked coined the term "[[cell (biology)|cell]]" to refer to the structural and functional unit of living organisms and designed a number of well-known buildings in [[London]]. Labeled by historians as "London's [[Leonardo da Vinci|Leonardo]]" (da Vinci) (Bennett et al. 2003), "England's Leonardo" (Chapman 2004), and the "Forgotten Genius" (Inwood 2002), Hooke invented the iris diaphragm used in [[camera]]s, the balance wheel used in watches, and the universal joint used in motor vehicles (RHSC 2003); he also elucidated Hooke's law of [[elasticity]], investigated possible means to achieve [[flight]], made [[astronomy|astronomical observations]], and examined [[gravity|gravitation]], among other pursuits. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Hooke left a remarkably broad legacy, extending from his microscope design and drawing of cells in cork to major buildings he designed that are still standing in London. His legacy might have been broader still had he and Sir [[Isaac Newton]] been able to collaborate harmoniously in the work that led to Newton's ''[[Principia]]'', which opened new vistas of scientific investigation. Instead, whatever collaboration the two apparently did have concluded with Newton claiming full credit for the ideas, while Hooke protested strongly but futilely for some share of the credit. The acrimony between Hook and Newton was so strong that Newton, who outlived Hooke by more than twenty years and oversaw the move to new quarters by the [[Royal Society]] after Hooke died, is thought to have had some responsibility for Hooke's portrait being lost in the move. No portrait of Hooke exists today. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Early life== |

| − | + | Hooke was born in Freshwater on the [[Isle of Wight]], an island off the southern English coast. His father was John Hooke, curate of the Church of All Saints, in Freshwater. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | From early childhood, Hooke was fascinated by the sciences. Like his three brothers (all ministers), Robert was expected to succeed in his education and join his father's church. However, Hooke continually suffered from headaches while studying. His parents, fearing he would not reach adulthood, decided to give up on his [[education]] and leave him to his own devices. | |

| + | Hooke received his early education on the Isle of Wight and, from about the age of 13, at Westminster School under Dr. Busby. In 1653, Hooke secured a chorister's place at Christ Church, [[University of Oxford|Oxford]]. There he met the chemist (and physicist) [[Robert Boyle]] and gained employment as his assistant. It is possible that Hooke formally stated [[Boyle's Law]], as Boyle was not a mathematician. | ||

| + | ==Career== | ||

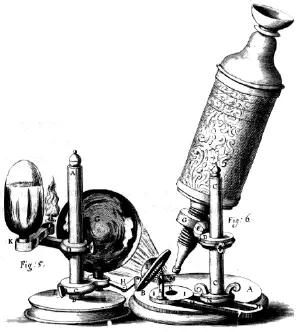

| + | [[Image:Microscope de HOOKE.png|300px|right|thumb|Robert Hooke's [[microscope]] (1665)—an [[engineering|engineered]] device used to study living systems]] | ||

| + | In 1660, Hooke elucidated [[Hooke's law|Hooke's Law]] of [[Elasticity (physics)|elasticity]], which describes the linear variation of [[tension (mechanics)|tension]] with extension in an [[elasticity (solid mechanics)|elastic]] spring. In 1662, Hooke gained appointment as curator of experiments to the newly founded [[Royal Society]], and took responsibility for experiments performed at its meetings. | ||

| + | In 1665, Hooke published an important work titled ''Micrographia''. This book contained a number of [[microscope|microscopic]] and [[telescope|telescopic]] observations, and some original observations in [[biology]]. In the book, Hooke coined the biological term ''[[cell (biology)|cell]]'', so called because his observations of [[plant]] cells reminded him of [[monk]]s' cells, which were called "cellula." Hooke is often credited with the discovery of the cell, and although his microscope was very basic, research by British scientist Brian J. Ford has now shown that Hooke could have observed [[cork]] cells with it. Ford furthermore shows that Hooke used more high-power single lenses to make many of his studies. He also has identified a section in the preface that contains a description of how to make a microscope, and Hooke's design was utilized by the Dutchman [[Anton van Leeuwenhoek]], described as the father of [[microbiology]]. | ||

| + | The hand-crafted, leather, and gold-tooled microscope that Hooke used to make the observations for ''Micrographia'', originally made by Christopher Cock in [[London]], is on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in [[Washington, D.C.]] | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|The English [[polymath]] Robert Hooke, credited with numerous important discoveries and inventions, has been called "England's Leonardo" }} | ||

| + | In 1665, Hooke also gained appointment as professor of [[geometry]] at Gresham College. Hooke also achieved fame as surveyor to the City of London and chief assistant of [[Christopher Wren]], helping to rebuild London after the Great Fire in 1666. He worked on designing the monument, Royal Greenwich Observatory, and the infamous Bethlem Royal Hospital (which became known as 'Bedlam'). | ||

| + | Hooke's first confrontation with [[Isaac Newton]] was in 1672, when Newton's presentation on white light being a composite of other colors was rebuffed by Hooke (O'Connor and Robertson 2002). Indeed, Newton threatened to leave the Royal Society, but was convinced to stay. In 1684, the confrontation between Hooke and Newton was major, concerning Newton's work on ''Principia'' and the role that Hooke had in it, with Hooke claiming to be involved (and seemingly was), but Newton not willing to give him any credit (O'Connor and Robertson 2002). It was in the ''Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica'' (now known as the ''Principia''), published on July 5, 1687, where Newton stated the three universal laws of motion that were not to be improved upon for more than two hundred years. The ''Principia'' was published without any recognition of Hooke's contribution. | ||

| + | Hooke died in London on March 3, 1703. He amassed a sizable sum of money during his career in London, which was found in his room at Gresham College after his death. He never married. | ||

| − | + | == Architect == | |

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:MK WillenChurch01.JPG|thumb|300px|The church at Willen, Milton Keynes]] | [[Image:MK WillenChurch01.JPG|thumb|300px|The church at Willen, Milton Keynes]] | ||

| − | + | Hooke was also an important [[architect]]. He was the official London surveyor after the Great Fire of 1666, surveying about half the plots in the city. In addition to the Bethlem Royal Hospital, other buildings designed by Hooke include the Royal College of Physicians (1679); Ragley Hall in Warwickshire, and the parish church at Willen, [[Milton Keynes]] (historical Buckinghamshire). | |

| − | Hooke's collaboration with [[Christopher Wren]] was particularly fruitful and yielded The Royal Observatory at Greenwich, | + | Hooke's collaboration with [[Christopher Wren]] was particularly fruitful and yielded The Royal Observatory at [[Greenwich]], The Monument (to the Great Fire), and [[St. Paul's Cathedral]], whose dome uses a method of construction conceived by Hooke. Specifically, he determined that the ideal shape of an [[arch]] is an inverted catenary (the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field), and thence that a circular series of such arches makes an ideal shape for a dome: It is his principle that crowns the [[cathedral]] (Gribbin and Gribbin 2017). |

| − | In the reconstruction after the Great Fire, Hooke proposed redesigning London's streets on a grid pattern with wide boulevards and arteries along the lines of the [[Champs-Élysées]] | + | In the reconstruction after the Great Fire, Hooke also proposed redesigning London's streets on a grid pattern with wide boulevards and arteries along the lines of the [[Champs-Élysées]] (this pattern was subsequently used for [[Liverpool]] and many American cities), but was prevented by problems over property rights. Many property owners were surreptitiously shifting their boundaries and disputes were rife. (Hooke was in demand to use his competence as a surveyor and tact as an arbitrator to settle many of these disputes.) So London was rebuilt along the original mediaeval streets. It is interesting to note that much of the modern-day curse of congestion in London has its origin in these disputes of the seventeenth century. |

| − | == | + | ==Portrait?== |

| − | + | It seems that no authenticated portrait of Hooke survives (Newton instigated the removal of Hooke's portrait in the Royal Society) (Scott 2021). In 2003, the historian Lisa Jardine claimed a recently discovered portrait represents Hooke. However, Jardine's hypothesis was soon refuted by William Jensen (University of Cincinnati) and independently by the German researcher Andreas Pechtl (Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz). The portrait generally is held to represent Jan Baptist van Helmont. | |

| − | + | A seal used by Hooke displays an unusual profile portrait of a man's head, that some have argued portrays Hooke. This likewise remains in dispute, however. Moreover, the engraved frontispiece to the 1728 edition of ''Chambers' Cyclopedia'' shows as an interesting detail the bust of Hooke. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | *[[ | + | * Bennett, J., M. Cooper, M. Hunter, and L. Jardine. 2003. ''London's Leonardo: The Life and Work of Robert Hooke''. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198525796 |

| − | * | + | * Chapman, A. 2004. ''England's Leonardo: Robert Hooke and the Seventeenth-century Scientific Revolution''. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0750309873 |

| + | * Chapman, A., and P. Kent (eds.). 2005. ''Robert Hooke and the English Renaissance''. Gracewing. ISBN 0852445873 | ||

| + | * Gribbin, John, and Mary Gribbin, Mary. 2017. ''Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley and the birth of British science''. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0008220594 | ||

| + | * 'Espinasse, M. 1956. ''Robert Hooke''. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. | ||

| + | * Hooke, R. 1961 [1665]. ''Micrographia; or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon''. New York: Dover Publications. | ||

| + | * Inwood, S. 2002. ''The Man Who Knew Too Much''. Pan Books. ISBN 0330488295 | ||

| + | * O'Connor, J.J., and E.F. Robertson. 2002. [https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Hooke/ Robert Hooke] ''MacTutor''. Retrieved March 15, 2024. | ||

| + | * Jardine, L. 2003. ''The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man who Measured London''. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0007149441 | ||

| + | * Robert Hooke Science Centre (RHSC 2003). [http://roberthooke.org.uk/ Robert Hooke Science Centre.] Retrieved March 15, 2024. | ||

| + | * Scott, Michon. 2021. [http://www.strangescience.net/hooke.htm Robert Hooke] ''Strange Science''. Retrieved March 15, 2024. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|126562950}} | {{credit|126562950}} | ||

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Biographies_of_Scientists_and_Mathematicians]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Biologists]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Cell biology]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Microbiology]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:09, 15 March 2024

Robert Hooke (July 18, 1635 – March 3, 1703) was an English polymath, a scientist, mathematician, and architect, who played an important role in the scientific revolution, through both experimental and theoretical work.

Hooked coined the term "cell" to refer to the structural and functional unit of living organisms and designed a number of well-known buildings in London. Labeled by historians as "London's Leonardo" (da Vinci) (Bennett et al. 2003), "England's Leonardo" (Chapman 2004), and the "Forgotten Genius" (Inwood 2002), Hooke invented the iris diaphragm used in cameras, the balance wheel used in watches, and the universal joint used in motor vehicles (RHSC 2003); he also elucidated Hooke's law of elasticity, investigated possible means to achieve flight, made astronomical observations, and examined gravitation, among other pursuits.

Hooke left a remarkably broad legacy, extending from his microscope design and drawing of cells in cork to major buildings he designed that are still standing in London. His legacy might have been broader still had he and Sir Isaac Newton been able to collaborate harmoniously in the work that led to Newton's Principia, which opened new vistas of scientific investigation. Instead, whatever collaboration the two apparently did have concluded with Newton claiming full credit for the ideas, while Hooke protested strongly but futilely for some share of the credit. The acrimony between Hook and Newton was so strong that Newton, who outlived Hooke by more than twenty years and oversaw the move to new quarters by the Royal Society after Hooke died, is thought to have had some responsibility for Hooke's portrait being lost in the move. No portrait of Hooke exists today.

Early life

Hooke was born in Freshwater on the Isle of Wight, an island off the southern English coast. His father was John Hooke, curate of the Church of All Saints, in Freshwater.

From early childhood, Hooke was fascinated by the sciences. Like his three brothers (all ministers), Robert was expected to succeed in his education and join his father's church. However, Hooke continually suffered from headaches while studying. His parents, fearing he would not reach adulthood, decided to give up on his education and leave him to his own devices.

Hooke received his early education on the Isle of Wight and, from about the age of 13, at Westminster School under Dr. Busby. In 1653, Hooke secured a chorister's place at Christ Church, Oxford. There he met the chemist (and physicist) Robert Boyle and gained employment as his assistant. It is possible that Hooke formally stated Boyle's Law, as Boyle was not a mathematician.

Career

In 1660, Hooke elucidated Hooke's Law of elasticity, which describes the linear variation of tension with extension in an elastic spring. In 1662, Hooke gained appointment as curator of experiments to the newly founded Royal Society, and took responsibility for experiments performed at its meetings.

In 1665, Hooke published an important work titled Micrographia. This book contained a number of microscopic and telescopic observations, and some original observations in biology. In the book, Hooke coined the biological term cell, so called because his observations of plant cells reminded him of monks' cells, which were called "cellula." Hooke is often credited with the discovery of the cell, and although his microscope was very basic, research by British scientist Brian J. Ford has now shown that Hooke could have observed cork cells with it. Ford furthermore shows that Hooke used more high-power single lenses to make many of his studies. He also has identified a section in the preface that contains a description of how to make a microscope, and Hooke's design was utilized by the Dutchman Anton van Leeuwenhoek, described as the father of microbiology.

The hand-crafted, leather, and gold-tooled microscope that Hooke used to make the observations for Micrographia, originally made by Christopher Cock in London, is on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C.

In 1665, Hooke also gained appointment as professor of geometry at Gresham College. Hooke also achieved fame as surveyor to the City of London and chief assistant of Christopher Wren, helping to rebuild London after the Great Fire in 1666. He worked on designing the monument, Royal Greenwich Observatory, and the infamous Bethlem Royal Hospital (which became known as 'Bedlam').

Hooke's first confrontation with Isaac Newton was in 1672, when Newton's presentation on white light being a composite of other colors was rebuffed by Hooke (O'Connor and Robertson 2002). Indeed, Newton threatened to leave the Royal Society, but was convinced to stay. In 1684, the confrontation between Hooke and Newton was major, concerning Newton's work on Principia and the role that Hooke had in it, with Hooke claiming to be involved (and seemingly was), but Newton not willing to give him any credit (O'Connor and Robertson 2002). It was in the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (now known as the Principia), published on July 5, 1687, where Newton stated the three universal laws of motion that were not to be improved upon for more than two hundred years. The Principia was published without any recognition of Hooke's contribution.

Hooke died in London on March 3, 1703. He amassed a sizable sum of money during his career in London, which was found in his room at Gresham College after his death. He never married.

Architect

Hooke was also an important architect. He was the official London surveyor after the Great Fire of 1666, surveying about half the plots in the city. In addition to the Bethlem Royal Hospital, other buildings designed by Hooke include the Royal College of Physicians (1679); Ragley Hall in Warwickshire, and the parish church at Willen, Milton Keynes (historical Buckinghamshire).

Hooke's collaboration with Christopher Wren was particularly fruitful and yielded The Royal Observatory at Greenwich, The Monument (to the Great Fire), and St. Paul's Cathedral, whose dome uses a method of construction conceived by Hooke. Specifically, he determined that the ideal shape of an arch is an inverted catenary (the curve that an idealized hanging chain or cable assumes under its own weight when supported only at its ends in a uniform gravitational field), and thence that a circular series of such arches makes an ideal shape for a dome: It is his principle that crowns the cathedral (Gribbin and Gribbin 2017).

In the reconstruction after the Great Fire, Hooke also proposed redesigning London's streets on a grid pattern with wide boulevards and arteries along the lines of the Champs-Élysées (this pattern was subsequently used for Liverpool and many American cities), but was prevented by problems over property rights. Many property owners were surreptitiously shifting their boundaries and disputes were rife. (Hooke was in demand to use his competence as a surveyor and tact as an arbitrator to settle many of these disputes.) So London was rebuilt along the original mediaeval streets. It is interesting to note that much of the modern-day curse of congestion in London has its origin in these disputes of the seventeenth century.

Portrait?

It seems that no authenticated portrait of Hooke survives (Newton instigated the removal of Hooke's portrait in the Royal Society) (Scott 2021). In 2003, the historian Lisa Jardine claimed a recently discovered portrait represents Hooke. However, Jardine's hypothesis was soon refuted by William Jensen (University of Cincinnati) and independently by the German researcher Andreas Pechtl (Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz). The portrait generally is held to represent Jan Baptist van Helmont.

A seal used by Hooke displays an unusual profile portrait of a man's head, that some have argued portrays Hooke. This likewise remains in dispute, however. Moreover, the engraved frontispiece to the 1728 edition of Chambers' Cyclopedia shows as an interesting detail the bust of Hooke.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bennett, J., M. Cooper, M. Hunter, and L. Jardine. 2003. London's Leonardo: The Life and Work of Robert Hooke. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198525796

- Chapman, A. 2004. England's Leonardo: Robert Hooke and the Seventeenth-century Scientific Revolution. Institute of Physics Publishing. ISBN 0750309873

- Chapman, A., and P. Kent (eds.). 2005. Robert Hooke and the English Renaissance. Gracewing. ISBN 0852445873

- Gribbin, John, and Mary Gribbin, Mary. 2017. Out of the Shadow of a Giant: Hooke, Halley and the birth of British science. London: William Collins. ISBN 978-0008220594

- 'Espinasse, M. 1956. Robert Hooke. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Hooke, R. 1961 [1665]. Micrographia; or, Some Physiological Descriptions of Minute Bodies Made by Magnifying Glasses, With Observations and Inquiries Thereupon. New York: Dover Publications.

- Inwood, S. 2002. The Man Who Knew Too Much. Pan Books. ISBN 0330488295

- O'Connor, J.J., and E.F. Robertson. 2002. Robert Hooke MacTutor. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- Jardine, L. 2003. The Curious Life of Robert Hooke: The Man who Measured London. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0007149441

- Robert Hooke Science Centre (RHSC 2003). Robert Hooke Science Centre. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- Scott, Michon. 2021. Robert Hooke Strange Science. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.