Difference between revisions of "Robert Boyle" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

<div align="center">[[Image:boyle-hooke.jpg|300px]]</div> | <div align="center">[[Image:boyle-hooke.jpg|300px]]</div> | ||

| − | When Boyle read of [[Otto von Guericke]]*'s air pump in 1657, he began, with | + | When Boyle read of [[Otto von Guericke]]*'s air pump in 1657, he began, with his assistant [[Robert Hooke]] (1635–1703), to devise improvements in its construction. As a result, they produced the "machina Boyleana" or "Pneumatical Engine" in 1659. He then started a series of experiments on the properties of air. |

| − | In 1660, Boyle published a book titled ''New Experiments Physico- | + | In 1660, Boyle published a book titled ''New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and Its Effects'', in which he described his experiments with the air pump. He concluded, among other things, that air has elasticity and weight and exerts pressure. He also reported that sound cannot traverse a vacuum, and air is necessary for creatures to live and materials to burn. On a more fundamental level, his experimental results led him to think of matter as composed of minute particles that he called ''corpuscles''. He thus distanced himself from Aristotelian ideas about forms and qualities, choosing to think of matter in terms of particles. |

| − | Among the critics of the views put | + | Among the critics of the views put forth in that book was a [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]]*, Franciscus Linus (1595–1675). In the course of answering Linus' objections, Boyle enunciated the principle that the volume of a gas varies inversely as its pressure—a principle that is commonly known as Boyle's Law among English-speaking peoples, although on the European continent it is attributed to [[Edme Mariotte]]*, who did not publish it until 1676. |

In 1663, the Invisible College became the [[Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge]]*. The charter of incorporation granted by [[Charles II of England]]* named Boyle a member of the council. In 1680, he was elected president of the society, but he declined the honor based on a scruple about oaths. | In 1663, the Invisible College became the [[Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge]]*. The charter of incorporation granted by [[Charles II of England]]* named Boyle a member of the council. In 1680, he was elected president of the society, but he declined the honor based on a scruple about oaths. | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

[[Image:000a.jpg|250px|right|thumb|Title page of ''The Scepitcal Chymist'']] | [[Image:000a.jpg|250px|right|thumb|Title page of ''The Scepitcal Chymist'']] | ||

| − | In 1661, Boyle published ''The Sceptical Chymist'' as a dialog in which he argued against the blind acceptance of authority in matters of science and demanded that the question "why?" should be addressed in every inquiry into the truth of matters. In addition, he strongly advocated the "proof" of results that are claimed to demonstrate a particular principle. In this sense, he was a true exponent of [[Francis Bacon]] | + | In 1661, Boyle published ''The Sceptical Chymist'' as a dialog in which he argued against the blind acceptance of authority in matters of science and demanded that the question "why?" should be addressed in every inquiry into the truth of matters. In addition, he strongly advocated the "proof" of results that are claimed to demonstrate a particular principle. In this sense, he was a true exponent of the views of [[Francis Bacon]]. For Boyle, the so-called "new philosophy" was experimental science. His scientific investigations and the sheer volume of his experimental records put him well beyond the philosophical or speculative natural philosophers. |

| − | In "The Sceptical Chymist" and other works, | + | Boyle was an alchemist in the sense that he believed it possible to transmute matter from one form to another. Nonetheless, he was clearly motivated by the quest for truth rather than by the desire for gold. In "The Sceptical Chymist" and other works, he criticized ideas inherited from the ancient Greeks, including Aristotle, about the elements of matter being such things as air, earth, fire, and water. Moreover, he did not accept the views of [[Paracelsus]] (1493–1541), the alchemist who thought of mercury, sulfur, and salt as the fundamental principles of things. |

| − | |||

| − | + | For Boyle, the simplistic "principles" of the more modern Paracelsus, ie: mercury, sulfer and salt. were not in accord with his own discoveries. Unlike the popular alchemists, Boyle would not accept salt, sulfur, and mercury as the "true principle of things" he stated that matter is made up of corpuscles which can be grouped into chemical substances and compounds. Boyle defined the distinction between mixtures and compounds and can rightly be called the Father of modern Chemistry. | |

Boyle's writing show that he defined the fundamental elements of matter as "primitive and simple, perfectly unmingled bodies." For Boyle an element must be a real material substance identifiable only by | Boyle's writing show that he defined the fundamental elements of matter as "primitive and simple, perfectly unmingled bodies." For Boyle an element must be a real material substance identifiable only by | ||

He made a clear distinction between mixtures, compounds and elements. The revolution in chemistry advocated by Boyle was a call for a systematic organization of experiments and the knowledge gained thereby. His advocacy must have deeply impressed his student Nicholas Lemery, who published a systematic chemistry text, ''Cours de Chemie''. This book was widely used in the study of chemistry for the next 50 years. | He made a clear distinction between mixtures, compounds and elements. The revolution in chemistry advocated by Boyle was a call for a systematic organization of experiments and the knowledge gained thereby. His advocacy must have deeply impressed his student Nicholas Lemery, who published a systematic chemistry text, ''Cours de Chemie''. This book was widely used in the study of chemistry for the next 50 years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | * His call for a "healthy skepticism," however, was not an original idea. It followed similar developments in the history of astromomy and medicine (Leonard Bruno, 1989). | ||

Revision as of 20:37, 16 September 2006

The Honorable Robert Boyle (January 25, 1627 – December 30, 1691) was an Irish natural philosopher (chemist, physicist, and inventor), noted for his work in physics and chemistry. He was an elder contemporary of Isaac Newton. Although his research and personal philosophy clearly has its roots in the alchemical tradition, he is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist. Among his works, The Sceptical Chymist is seen as a cornerstone book in the field of chemistry.

Early years

Born at Lismore Castle in the province of Munster, Ireland, Robert was the seventh son and fourteenth child of Richard Boyle, the "Great Earl of Cork." While still a child, he learned to speak Latin, Greek, and French, and he was only eight years old when he was sent to Eton College, of which his father's friend, Sir Henry Wotton, was then provost. After studying at the college for more than three years, he traveled abroad with a French tutor and spent nearly two years in Geneva.

During his stay in Geneva, Boyle had a sudden, "rebirth" experience through which he made a deeper commitment to his Christian faith than mere acceptance of a religious doctrine. A severe thunderstorm on a summer's night led him to commit himself to a sincere and devoted religious life. In keeping with his character, he renewed the commitment on a cloudless, serene day, with the understanding that a promise made in fear was not as serious as one made with calm intention.

This promise to God may have led to Boyle's later commitment to the advancement of science for the benefit of mankind. In addition, he later emphasized the need for each individual to have an examined faith rather than accepting a faith on the basis of what one is taught as a child in a believing home.

While in Geneva, Boyle seems to have engaged in conversations with the philosopher Francois Perreaud, who later wrote about interactions between the spiritual and physical realms. Perreaud wrote a book that Boyle translated into English, dealing with philosophical and religious matters. Those philosophical ideas certainly influenced young Boyle's thoughts about the existence of invisible forces in nature. Such speculations naturally led him to consider the manner in which invisible forces might inteact with material objects in the visible world.

Middle years

Boyle remained on the continent until the summer of 1644. Apparently, politics and war made it difficult for him to receive his allowance. Back in England, he rejoined his sister Katherine, who had been a maternal figure for him. Their father soon died, leaving him the manor of Stalbridge in Dorset, together with estates in Ireland.

In 1649 at Stalbridge, Boyle dedicated his life to scientific study and research. He soon took a prominent place in the band of inquirers known as the "Invisible College," who devoted themselves to cultivation of the "new philosophy." They met frequently in London, often at Gresham College. Some of the members also had meetings at Oxford, and Boyle took up residence in that city in 1654.

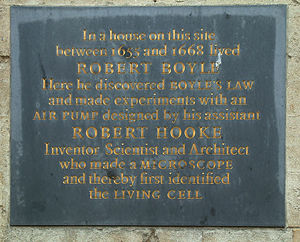

An inscription can be found on the wall of University College on High Street at Oxford, marking the spot where Cross Hall stood until the early 1800s. At this site, Boyle rented rooms from the wealthy apothecary who owned the Hall.

When Boyle read of Otto von Guericke's air pump in 1657, he began, with his assistant Robert Hooke (1635–1703), to devise improvements in its construction. As a result, they produced the "machina Boyleana" or "Pneumatical Engine" in 1659. He then started a series of experiments on the properties of air.

In 1660, Boyle published a book titled New Experiments Physico-Mechanical, Touching the Spring of the Air, and Its Effects, in which he described his experiments with the air pump. He concluded, among other things, that air has elasticity and weight and exerts pressure. He also reported that sound cannot traverse a vacuum, and air is necessary for creatures to live and materials to burn. On a more fundamental level, his experimental results led him to think of matter as composed of minute particles that he called corpuscles. He thus distanced himself from Aristotelian ideas about forms and qualities, choosing to think of matter in terms of particles.

Among the critics of the views put forth in that book was a Jesuit, Franciscus Linus (1595–1675). In the course of answering Linus' objections, Boyle enunciated the principle that the volume of a gas varies inversely as its pressure—a principle that is commonly known as Boyle's Law among English-speaking peoples, although on the European continent it is attributed to Edme Mariotte, who did not publish it until 1676.

In 1663, the Invisible College became the Royal Society of London for the Improvement of Natural Knowledge. The charter of incorporation granted by Charles II of England named Boyle a member of the council. In 1680, he was elected president of the society, but he declined the honor based on a scruple about oaths.

In 1661, Boyle published The Sceptical Chymist as a dialog in which he argued against the blind acceptance of authority in matters of science and demanded that the question "why?" should be addressed in every inquiry into the truth of matters. In addition, he strongly advocated the "proof" of results that are claimed to demonstrate a particular principle. In this sense, he was a true exponent of the views of Francis Bacon. For Boyle, the so-called "new philosophy" was experimental science. His scientific investigations and the sheer volume of his experimental records put him well beyond the philosophical or speculative natural philosophers.

Boyle was an alchemist in the sense that he believed it possible to transmute matter from one form to another. Nonetheless, he was clearly motivated by the quest for truth rather than by the desire for gold. In "The Sceptical Chymist" and other works, he criticized ideas inherited from the ancient Greeks, including Aristotle, about the elements of matter being such things as air, earth, fire, and water. Moreover, he did not accept the views of Paracelsus (1493–1541), the alchemist who thought of mercury, sulfur, and salt as the fundamental principles of things.

For Boyle, the simplistic "principles" of the more modern Paracelsus, ie: mercury, sulfer and salt. were not in accord with his own discoveries. Unlike the popular alchemists, Boyle would not accept salt, sulfur, and mercury as the "true principle of things" he stated that matter is made up of corpuscles which can be grouped into chemical substances and compounds. Boyle defined the distinction between mixtures and compounds and can rightly be called the Father of modern Chemistry.

Boyle's writing show that he defined the fundamental elements of matter as "primitive and simple, perfectly unmingled bodies." For Boyle an element must be a real material substance identifiable only by

He made a clear distinction between mixtures, compounds and elements. The revolution in chemistry advocated by Boyle was a call for a systematic organization of experiments and the knowledge gained thereby. His advocacy must have deeply impressed his student Nicholas Lemery, who published a systematic chemistry text, Cours de Chemie. This book was widely used in the study of chemistry for the next 50 years.

- His call for a "healthy skepticism," however, was not an original idea. It followed similar developments in the history of astromomy and medicine (Leonard Bruno, 1989).

smg++ Collaborating with his student, Robert Hooke, Boyle investigated the chemistry of combustion and observed many of the properties of what Lavoisier would later call "Oxygen".smg++

In 1668, he left Oxford for London, where he resided at the house of his sister, Lady Ranelagh, in Pall Mall.

Later years

About 1689, his health, never very strong, began to fail seriously and he gradually withdrew from his public engagements, ceasing his communications to the Royal Society, and advertising his desire to be excused from receiving guests, "unless upon occasions very extraordinary," on Tuesday and Friday forenoon, and Wednesday and Saturday afternoon. In the leisure thus gained he wished to "recruit his spirits, range his papers," and prepare some important chemical investigations which he proposed to leave "as a kind of Hermetic legacy to the studious disciples of that art," but of which he did not make known the nature. His health became still worse in 1691, and his death occurred on December 30 of that year, just a week after that of the sister with whom he had lived for more than twenty years. He was buried in the churchyard of St Martin's in the Fields, his funeral sermon being preached by his friend Bishop Burnet. In his will, Boyle endowed a series of Lectures which came to be known as the Boyle Lectures.

Scientific investigator

Boyle's great merit as a scientific investigator is that he carried out the principles which Francis Bacon preached in the Novum Organum. Yet he would not avow himself a follower of Bacon, or indeed of any other teacher. On several occasions he mentions that in order to keep his judgment as unprepossessed as might be with any of the modern theories of philosophy, till he was "provided of experiments" to help him judge of them, he refrained from any study of the Atomical and the Cartesian systems, and even of the Novum Organum itself, though he admits to "transiently consulting" them about a few particulars. Nothing was more alien to his mental temperament than the spinning of hypotheses. He regarded the acquisition of knowledge as an end in itself, and in consequence he gained a wider outlook on the aims of scientific inquiry than had been enjoyed by his predecessors for many centuries. This, however, did not mean that he paid no attention to the practical application of science nor that he despised knowledge which tended to use.

++goldberg++Boyle had a lot to say about experimenting. He seems to have been the first natural philosopher to establish that the suppositions employed in setting up an experiment must be validated before proceding with the experiment itself. There is something in Boyle's approach akin to a mathematician's insistance on fundamental truths (such as the establishment of geometrical theorems before proofs can be shown for example).

According to Rose-Mary Sargent there is the meeting of practical and philosophical elements in Boyle's written works. Boyle demanded that the experimenter think about what he is trying to understand and clarify his methods before he can start experimentation. He must devise instruments with which to make trials (for example the vacuum pump he made famous in his exploration of pressure and compression of air). end added section by ++ Goldberg++

He himself was an alchemist; and believing the transmutation of metals to be a possibility, he carried out experiments in the hope of effecting it; and he was instrumental in obtaining the repeal, in 1689, of the statute of Henry IV against multiplying gold and silver. With all the important work he accomplished in physics - the enunciation of Boyle's law, the discovery of the part taken by air in the propagation of sound, and investigations on the expansive force of freezing water, on specific gravities and refractive powers, on crystals, on electricity, on colour, on hydrostatics, etc.- chemistry was his peculiar and favourite study. His first book on the subject was The Sceptical Chemist, published in 1661, in which he criticized the "experiments whereby vulgar Spagyrists are wont to endeavour to evince their Salt, Sulphur and Mercury (element) to be the true Principles of Things." For him chemistry was the science of the composition of substances, not merely an adjunct to the arts of the alchemist or the physician. He advanced towards the modern view of elements as the undecomposable constituents of material bodies; and understanding the distinction between mixtures and compounds, he made considerable progress in the technique of detecting their ingredients, a process which he designated by the term "analysis." He further supposed that the elements were ultimately composed of particles of various sorts and sizes, into which, however, they were not to be resolved in any known way. Applied chemistry had to thank him for improved methods and for an extended knowledge of individual substances. He also studied the chemistry of combustion and of respiration, and conducted experiments in physiology, where, however, he was hampered by the "tenderness of his nature" which kept him from anatomical dissections, especially of living animals, though he knew them to be "most instructing."

Besides being a busy natural philosopher, Boyle devoted much time to theology, showing a very decided leaning to the practical side and an indifference to controversial polemics. ==Goldberg==Boyle saw the study of nature and of science as an act of worship or of religion because through these studies man could gain an understanding of the Divine Attributes.

Some religionists feared the study of nature would lead to nature worship and away from God. Boyle thought otherwise and published a book titled, "The Usefulness of Natural Philosophy" in which he arged that reason alone leads to the conclusion that study of God's work will not lead to atheism. Instead he saw the book of nature as worthy of glorifiying God by study. In fact to neglect the study of nature would be an insult to the Creator. ++END GOLDBERG ADD++

At the Restoration he was favourably received at court, and in 1665 would have received the provostship of Eton, if he would have taken orders; but this he refused to do on the ground that his writings on religious subjects would have greater weight coming from a layman than a paid minister of the Church. As a director of the East India Company he spent large sums in promoting the spread of Christianity in the East, contributing liberally to missionary societies, and to the expenses of translating the Bible or portions of it into various languages. He founded the Boyle lectures, intended to defend the Christian religion against those he considered "notorious infidels, namely atheists, theists, pagans, Jews and Muslims," with the proviso that controversies between Christians were not to be mentioned.

In person Boyle was tall, slender and of a pale countenance. His constitution was far from robust, and throughout his life he suffered from feeble health and low spirits. While his scientific work procured him an extraordinary reputation among his contemporaries, his private character and virtues, the charm of his social manners, his wit and powers of conversation, endeared him to a large circle of personal friends. He was never married. His writings are exceedingly voluminous, and his style is clear and straightforward, though undeniably prolix.

In 2004 The Robert Boyle Science Room was opened in the Lismore Heritage Centre, near his birthplace, dedicated to his life and works where students have the opportunity of studying science and participating in scientific experiments.

Important works

The following are the more important of Boyle's works:

- 1660 - New Experiments Physico-Mechanical: Touching the Spring of the Air and their Effects

- 1661 - The Sceptical Chymist

- 1663 - Considerations touching the Usefulness of Experimental Natural Philosophy (followed by a second part in 1671)

- 1663 - Experiments and Considerations upon Colours, with Observations on a Diamond that Shines in the Dark

- 1665 - New Experiments and Observations upon Cold

- 1666 - Hydrostatical Paradoxes

- 1666 - Origin of Forms and Qualities according to the Corpuscular Philosophy

- 1669 - a continuation of his work on the spring of air

- 1670 - tracts about the Cosmical Qualities of Things, the Temperature of the Subterraneal and Submarine Regions, the Bottom of the Sea, &c. with an Introduction to the History of Particular Qualities

- 1672 - Origin and Virtues of Gems

- 1673 - Essays of the strange Subtilty, great Efficacy, determinate Nature of l3ffiuvi urns

- 1674 - two volumes of tracts on the Saitness of the Sea, the Hidden Qualities of the Air, Cold, Celestial Magnets, Animadversions on Ijobbes's Problemata de Vacuo

- 1676 - Experiments and Notes about the Mechanical Origin or Production of Particular Qualities, including some notes on electricity and magnetism

- 1678 - Observations upon an artificial Substance that Shines without any Preceding Illustration

- 1680 - the Aerial Noctiluca

- 1682 - New Experiments and Observations upon the Icy Noctiluca

- 1682 - a further continuation of his work on the air

- 1684 - Memoirs for the Natural History of the Human Blood

- 1685 - Short Memoirs for the Natural Experimental History of Mineral Waters

- 1690 - Medic-ma Hydrostatica

- 1691 - Experimentae et Observationes Physicae

Among his religious and philosophical writings were:

- 1648/1660 - Seraphic Love, written in 1648, but not published till 1660

- 1663 - an Essay upon the Style of the Holy Scriptures

- 1664 - Excellence of Theology compared with Natural Philosophy

- 1665 - Occasional Reflections upon Several Subjects, which was ridiculed by Swift in A Pious Meditation upon a Broom Stick, and by Butler in An Occasional Reflection on Dr Charlton's Feeling a Dog's Pulse at Gresham College

- 1675 - Some Considerations about the Reconcileableness of Reason and Religion, with a Discourse about the Possibility of the Resurrection

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Leonard C. Bruno (1989), The Landmarks of Science. ISBN 0-8160-2137-6

- Rose-Mary Sargent (1995), The Diffident Naturalist: Robert Boyle and the Philosophy of Experiment, University of Chicago Press.

- Thomas Birch (1772; reprinted 1996) The Works of the Honorable Robert Boyle.

- Stephen Shapin and Simon Schaffer, Leviathan and the Air-Pump

- Lawrence Principe, The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest

- Boyle was an alchemist and as such was looking for the "Philosopher's Stone, an object which would transmute base metals into gold and attract angels.

As a lifelong student of alchemy, Robert Boyle appears to have been very much on the cusp of the development of modern science on a foundation of earlier philosophies which dealt with the phenomena of changing states and essences of matter.

- Notes

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Template:A Short Biographical Dictionary of English Literature

See also

External links

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke

- Works by Robert Boyle. Project Gutenberg

- The Sceptical Chymist University of Pennsylvania Library e-text

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.