Philosophy of mind

Philosophy of mind is the branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind, mental events, mental functions, mental properties and consciousness, and their relationship to the physical body. The mind-body problem, i.e. the question of how the mind relates to the body, is commonly seen as the central issue in philosophy of mind, although there are other issues concerning the nature of the mind that do not involve its relation to the physical body.

Dualism and monism are the two major schools of thought that attempt to resolve the mind-body problem. Dualism is the position that mind and body are in some way separate from each other. It can be traced back at least to Plato,[1] Aristotle[2][3][4] and the Sankhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy,[5] but received its most influential formulation by René Descartes in the 17th century.[6] Substance dualists argue that the mind is an independently existing substance, whereas Property dualists maintain that the mind is a group of independent properties that emerge from and cannot be reduced to the brain, though they are ontologically dependent on it.[7]

Monism rejects the dualist separation and maintains that mind and body are, at the most fundamental level, of the same kind. This view seems to have first been advocated in Western Philosophy by Parmenides in the 5th Century B.C.E. and was later espoused by the 17th Century rationalist Baruch Spinoza.[8] Rough parallels in Eastern Philosophy might be the Hindu concept of Brahman or the Tao of Lao Tzu. Physicalists argue that only the entities postulated by physical theory exist, and that mind is ultimately nothing more than such physical entities. Idealists maintain that minds (along with their perceptions and ideas) are all that exists and that the external world is either mental itself, or an illusion created by the mind. The most common monisms in the 20th and 21st centuries have all been variations of physicalism; these positions include behaviorism, the type identity theory, and anomalous monism.[9]

Many modern philosophers of mind adopt either a reductive or non-reductive physicalist position, maintaining in their different ways that only the mind is not something separate from the brain. [9] Reductivists assert that all mental states and properties can in principle be explained by neuroscientific accounts of brain processes and states.[10][11][12] Non-reductionists argue that although the brain is all there is to the mind, mental states and properties cannot ultimately be explained in the terms of the physical sciences (such a view is often expressed by focusing on predicates of a mental sort, such as 'is seeing red').[13][14] Continued neuroscientific progress has helped to clarify some of these issues. However, they are far from having been resolved, and modern philosophers of mind continue to ask how the subjective qualities and the intentionality (aboutness) of mental states and properties can be explained in the terms of the natural sciences.[15][16]

The mind-body problem

The mind-body problem concerns the explanation of the relationship, if any, that obtains between minds, or mental processes, and bodily states or processes. One way to get an intuitive grip on the problem is to consider the following line of thought:

Each of us spends much of our day dealing with ordinary physical objects, like tables, chairs, cars, computers, food, etc. Though some of these objects are much more complex than others, they seem to have a great deal in common. This commonality is brought out by our belief that every feature of these objects can be explained by physics. Each object is clearly just a bunch of particles arranged in a certain way, so that (with sufficient energy) each could in principle be turned into another. In other words, they all seem to be made out of the same sort of stuff, and their properties are just a function of how that stuff is arranged. Intuitively, our bodies are no exceptions to this. While they are much more complex than any machine we can currently make, we believe our bodies are made up of the same stuff as our simplest machines (e.g. protons, neutrons and electrons).

At the same time, we also believe that there are mental things in the universe. If you and a friend are looking at a statue from different sides, you might ask your friend what her experience of the statue was like. You might then compare your experiences - while the color of the statue might have been more prominent in your experience, the shape might have been more prominent in hers. This just shows that we think that there's a certain kind of thing, an 'experience' that makes up part of the world, and we attribute these experiences to minds.

Now we ask: are these minds and their experiences a sort of physical object? Not obviously. Experiences don't seem to be made up of particles. They certainly seem to have some important relation to a certain set of particles (those that make up our brains and bodies), but if (for instance) we were to divide a brain in half, we wouldn't think that experiences would somehow split in half. Moreover, while it's clear that experiences can be about objects, it's not at all clear how some bunch of particles could be 'about' anything at all.

To put the point slightly differently, imagine that someone were describing a possible universe to you, and gave you a very long list of particle locations. No matter how detailed that list, it would seem that there's a very reasonable question you could ask: are there any minds in this universe? A certain arrangement of particles is clearly sufficient for a book to exist, but the same isn't obviously true for minds and experiences.

There are both metaphysical and epistemological aspects to this problem. On the metaphysical side, we might wonder about whether minds and bodies are distinct substances, whether they could exist independently of each other, and whether they have different properties. On the epistemological side, we might wonder whether neuroscience will ever be able to fully explain the nature of minds and experiences.

Dualist solutions to the mind-body problem

Dualism is a family of views about the relationship between mind and physical matter. It begins with the claim that mental phenomena are, in some respects, non-physical. One of the earliest known formulations of mind-body dualism was expressed in the eastern Sankhya and Yoga schools of Hindu philosophy (c. 650 B.C.E.), which divided the world into purusha (mind/spirit) and prakrti (material substance).[5]

In Western Philosophy, some of the earliest discussions of dualist ideas are in the writings of Plato and Aristotle. Each of these maintained, but for different reasons, that man's "intelligence" (a faculty of the mind or soul) could not be identified with, or explained in terms of, his physical body.[1][2] However, the best-known version of dualism is due to René Descartes (expressed in his 1641 Meditations on First Philosophy), and holds that the mind is a non-extended, non-physical substance.[6] Descartes was the first to clearly identify the mind with consciousness and self-awareness, and to distinguish this from the brain, which was the seat of intelligence.

Arguments for dualism

Two of the most famous arguments for dualism were given their classic formulations by Descartes. The first is often referred to as the Conceivability Argument. In broad outline, it runs as follows: though they presently exist together somehow, I am capable of forming a clear and distinct conception of my mind existing without my body, and an equally clear and distinct conception of my body existing without my mind. Unlike some other forms of imagining, clear and distinct perception is of an especially reliable sort (Descartes believed that that premise required an argument that God had given us our faculties and was not a deceiver), so we can conclude that the mind and body are indeed independent. The contemporary philosopher David Chalmers has recently provided detailed discussion and defense of this sort of argument.[17]

Descartes' second argument is often referred to as the Divisibility Argument. That outline proceeds roughly as follows: my body/brain and all its parts are divisible, yet my mind is utterly simple and indivisible, so my mind cannot be identical to my body/brain or any part thereof. This argument rests heavily on the notion of 'divisibility', and there is some challenge in finding an understanding of it that doesn't make the argument question-begging. A recent defense of a more sophisticated form of the Divisibility Argument can be found in Peter Unger's All the Power in the World.[18]

A popular contemporary line of argument in favor of dualism centers on the idea that the mental and the physical seem to have quite different, and perhaps irreconcilable, properties.[19] Mental events have a certain subjective quality to them, whereas physical events do not. So, for example, one can reasonably ask what a burnt finger feels like to a person, or what a blue sky looks like to a mind, or what nice music sounds like to the person hearing it. But it is meaningless, or at least odd, to ask what a surge in the uptake of glutamate in the dorsolateral portion of the hippocampus feels likes.

Philosophers of mind call the subjective aspects of mental events qualia (or raw feels).[19] There is something 'that it is like' to feel pain, to see a familiar shade of blue, and so on. There are qualia involved in these mental events that seem particularly difficult to reduce to or explain in terms of anything physical.[20]

Interactionist dualism

Interactionist dualism, or simply interactionism, is the particular form of dualism first espoused by Descartes in the Meditations.[6] In the 20th century, two of its major defenders have been Karl Popper and John Carew Eccles.[21]

This view makes a natural step beyond the basic claim that the mind and body are two distinct substances, and adds that they causally influence each other. One simple but clear case would be the following: something bites my arm, a signal is sent to my brain and then to my mind. My mind then makes the decision to brush the biting thing away, sending a message to my brain, which then sends a message to the arms to do the brushing.

The most difficult part of this story to make sense of concerns the communication between the (physical) brain and the (non-physical) mind. Descartes believed that the pineal glad in the center of the brain was the spot of communication, but could offer no further explanation. After all, while we have some grasp on the laws that govern communication of motion between physical bodies, and the psychological laws that describe how certain thoughts lead to other thoughts, no known set of laws seems fit to describe the way in which the physical and the mental (when conceived as non-physical) interact. Indeed, the sort of interaction in question seems to be inconceivable (an especially sensitive point for dualists who base their position on the Conceivability Argument).

Other forms of dualism

1) Psycho-physical parallelism, or simply parallelism, is the view that mind and body, while having distinct ontological statuses, do not causally influence one another. Instead, they run along parallel paths (mind events causally interact with mind events and brain events causally interact with brain events) and only seem to influence each other.[22] This view was most prominently defended by Gottfried Leibniz. Although Leibniz was an ontological monist who believed that only one fundamental substance, monads, exists in the universe and that everything (including physical matter) is reducible to it, he nonetheless maintained that there was an important distinction between "the mental" and "the physical" in terms of causation. He held that God had arranged things in advance so that minds and bodies would be in harmony with each other. This is known as the doctrine of pre-established harmony.[23]

2) Occasionalism is the view espoused most notably by Nicholas Malebranche which asserts that all supposedly causal relations between physical events, or between physical and mental events, are not really causal at all. While body and mind are still different substances, causes (whether mental or physical) are related to their effects by an act of God's intervention on each specific occasion.[24] For instance, my decision to raise my arm is merely the occasion on which God causes my arm to raise. Likewise, the motion of particles which constitute my finger's being pricked is the occasion on which God causes a sensation of pain to appear in my brain.

3) Epiphenomenalism is a doctrine first formulated by Shadworth Hodgson[25], but with precedents going back as far as Plato. Fundamentally, it consists in the view that mental phenomena are causally ineffectual. Physical events can cause other physical events and physical events can cause mental events, but mental events cannot cause anything, since they are just causally inert by-products (i.e. epiphenomena) of the physical world.[22] The view has been defended most strongly in recent times by Frank Jackson.[26]

4) Property dualism asserts that when matter is organized in the appropriate way (i.e. in the way that living human bodies are organized), mental properties emerge. Hence, it is a sub-branch of emergent materialism.[7] These emergent properties have an independent ontological status and cannot be reduced to, or explained in terms of, the physical substrate from which they emerge. This position is espoused by David Chalmers and has undergone something of a renaissance in recent years.[27] Unlike more traditional dualism, this view doesn't involve the claim that the mind is capable of existing independently of physical objects.

Monist solutions to the mind-body problem

In contrast to dualism, monism states that there is only one fundamental substance or type of substance. Today, the most common forms of monism in Western philosophy are physicalist.[9] Physicalistic monism asserts that the only existing substance is physical, in some sense of that term to be clarified by our best science.[28] Physicalism has been formulated in a wide variety of ways (see below).

Another form of monism, idealism, states that the only existing substance is mental. The most prominent defenders of that view in the Western tradition are Leibniz and the Irish Bishop George Berkeley.

Another possibility is to accept the existence of a basic substance which is neither exclusively physical nor exclusively mental. One version of such a position was adopted by the Dutch Jewish philosopher Baruch Spinoza[8], who held that God was the only substance in the world, and that all particular things (including minds and bodies) were merely affections of God. A rather different version was popularized by Ernst Mach[29] in the 19th century. This neutral monism, as it is called, bears some resemblence to property dualism.

Varieties of Physicalism

Prior to the 17th and 18th centuries, physics had accomplished relatively little, and theology set many of the starting points for science, making it easier for thinkers to assume that there was more to the universe than described in the language of physics. Today, the claim that physics is the most fundamental science, and that the truths of other sciences can in principle be reduced to the truths of physics, is seen by many as almost self-evident. Because of this, many philosophers have seen physicalism monism as irresistable, so that more intellectual energy has been devoted to developing varieties of this view of the mind than any other.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism dominated philosophy of mind for much of the 20th century, especially the first half.[9] In psychology, behaviorism developed as a reaction to the inadequacies of introspectionism.[28] Introspective reports on one's own interior mental life are not subject to careful examination for accuracy and can not be used to form predictive generalizations. Without generalizability and the possibility of third-person examination, the behaviorists argued, psychology cannot be scientific.[28] The way out, therefore, was to eliminate or ignore the idea of an interior mental life (and hence an ontologically independent mind) altogether and focus instead on the description of observable behavior.[30]

Parallel to these developments in psychology, a philosophical behaviorism (sometimes called logical behaviorism) was developed.[28] This was characterized by a strong verificationism, which generally considers unverifiable statements about interior mental life senseless. For the behaviorist, mental states are not interior states on which one can make introspective reports. They are just descriptions of behavior or dispositions to behave in certain ways, primarily made by third parties to explain and predict others' behavior.[31]

Philosophical behaviorism, has fallen out of favor since the latter half of the 20th century, coinciding with the rise of cognitive psychology.[32] Nearly all contemporary philosophers reject behaviorism, and it's not difficult to appreciate why. When I state that I'm having a headache, the behaviorist must deny that I'm referring to any sort of experience, and am merely making some claim about my dispositions. This would mean that "I have a headache" might be equivalent to saying "I currently have a disposition to close my eyes, rub my head, and consume some pain medicine." Yet those claims are clearly not equivalent - what it is to have a headache is just to be experiecing a certain pain. If anything, it seems that the dispositions in question are the result of that experience, not constitutive of it.

Identity theory

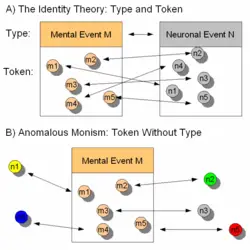

As the difficulties with behaviorism became increasingly apparent, physicalist-minded philosophers looked for other ways to claim that the mental was nothing beyond the physical that didn't require ignoring or denying the 'internal' aspect of mentality. Many of the post-behaviorist theories can be divided in terms of a distinction made by C. S. Pierce between 'tokens' and 'types.' Roughly speaking, 'token's are individual instances of 'types.' A token cat, then, is a particular cat, where as the type: cat is a category including a variety of tokens. This distinction allows for some subtlty in formulating claims about the relation of the mental to the physical.

Type physicalism (or type-identity theory) was developed in large part by John Smart[12] as a direct reaction to the failure of behaviorism. Smart and other philosophers reasoned that, if mental states are something material, but not simple behavioral dispositions, then types of mental states are probably identical to types of internal states of the brain. In very simplified terms: a mental state M is nothing other than brain state B. The mental state "desire for a cup of coffee" would thus be nothing more than the "firing of certain neurons in certain brain regions".[12] On such a view, it would turn out that any two people with a desire for a cup of coffee would have a similar type of neuronal firing pattern in similar regions of the brain.

Despite initial plausibility, the identity theory faces at least one challenge in the form of the multiple realizability thesis , as first formulated by Hilary Putnam.[14] It seems clear that not only humans, but also amphibians, for example, can experience pain. On the other hand, it seems very improbable that all of these diverse organisms with the same pain are in the same identical brain state. If this is not the case however, then pain (as a type) cannot be identical to a certain type of brain state. The ty[e identity theory thus appears to be empirically unfounded.[14] Despite these problems, there is a renewed interest in the type identity theory today, primarily due to the influence of Jaegwon Kim.[12]

But, even if this is the case, it does not follow that identity theories of all forms must be abandoned. According to token identity theories, the fact that a certain brain state is connected with only one "mental" state of a person does not have to mean that there is an absolute correlation between types of mental states and types of brain state. The idea of token identity is that only particular occurrences of mental events are identical with particular occurrences or tokenings of physical events.[33] Anomalous monism (see below) and most other non-reductive physicalisms are token-identity theories.[34] It is worth noting that that type identity entails token identity, but not vice-versa.

Functionalism

Functionalism was formulated by the American philosophers Hilary Putnam and Jerry Fodor as a reaction to the inadequacies of the type identity theory.[14] Putnam and Fodor saw mental states in terms of an empirical computational theory of the mind.[35] At about the same time or slightly after, D.M. Armstrong and David Kellogg Lewis formulated a version of functionalism which analyzed the mental concepts of folk psychology in terms of functional roles.[36] Finally, Wittgenstein's idea of meaning as use led to a version of functionalism as a theory of meaning, further developed by Wilfrid Sellars and Gilbert Harman. Functionalists have claimed to find a precedent for their view in Aristotle's De Anima.[37]

What all these different varieties of functionalism share in common is the thesis that mental states are essentially characterized by their causal relations with other mental states and with sensory inputs and behavioral outputs. That is, functionalism abstracts away from the details of the physical implementation of a mental state by characterizing it in terms of non-mental functional properties. For example, a kidney is characterized scientifically by its functional role in filtering blood and maintaining certain chemical balances. From this point of view, it does not really matter whether the kidney be made up of organic tissue, plastic nanotubes or silicon chips: it is the role that it plays and its relations to other organs that define it as a kidney.[35] This allows a fairly straightforward answer to the multiple realizability problem - while different organisms that experience the same mental state may differ in 'low-level' properties (such as specific arrangement of neurons, or even chemical composition), the functionalist claim merely requires that they share some more abstract property. Just as one can make a mousetrap out of any variety of materials and in any number of configurations, the functionalist view allows that a mind with mental states like ours could in principle be realized in a wide variety of ways.

Nonreductive physicalism

Many philosophers hold firmly to two essential convictions with regard to mind-body relations: 1) Physicalism is true and mental states must be physical states, and 2) All reductionist proposals are unsatisfactory: mental states cannot be reduced to behavior, brain states or functional states.[28] Hence, the question arises whether there can still be a non-reductive physicalism. Donald Davidson's anomalous monism[13] is an attempt to formulate such a physicalism.

The idea is often formulated in terms of the thesis of supervenience: mental states supervene on physical states, but are not reducible to them. "Supervenience" therefore describes a functional dependence: there can be no change in the mental without some change in the physical.[38]

Eliminative materialism

If one is a materialist but believes that all reductive efforts have failed and that a non-reductive materialism is incoherent, then one can adopt a final, more radical position: eliminative materialism. Eliminative materialists maintain that mental states are fictitious entities introduced by everyday "folk psychology".[10] Should "folk psychology", which eliminativists view as a quasi-scientific theory, be proven wrong in the course of scientific development, then we must also abolish all of the entities postulated by it.

Eliminativists such as Patricia and Paul Churchland often invoke the fate of other, erroneous popular theories and ontologies which have arisen in the course of history.[10][11] For example, the belief in witchcraft as a cause of people's problems turned out to be wrong and the consequence is that most people no longer believe in the existence of witches. Witchcraft is not explained in terms of some other phenomenon, but rather eliminated from the discourse.[11]

Linguistic criticism of the mind-body problem

Each attempt to answer the mind-body problem encounters substantial problems. Some philosophers argue that this is because there is an underlying conceptual confusion.[39] Such philosophers reject the mind-body problem as an illusory problem. Such a position is represented in analytic philosophy these days, for the most part, by the followers of Ludwig Wittgenstein and the Wittgensteinian tradition of linguistic criticism.[40] The exponents of this position explain that it is an error to ask how mental and biological states fit together. Rather it should simply be accepted that humans can be described in different ways - for instance, in a mental and in a biological vocabulary. Illusory problems arise if one tries to describe the one in terms of the other's vocabulary or if the mental vocabulary is used in the wrong contexts.[40] This is the case for instance, if one searches for mental states of the brain. The brain is simply the wrong context for the use of mental vocabulary - the search for mental states of the brain is therefore a category error or a pure conceptual confusion.[40]

Today, such a position is often adopted by interpreters of Wittgenstein such as Peter Hacker.[39] However, Hilary Putnam, the inventor of functionalism, has also adopted the position that the mind-body problem is an illusory problem which should be dissolved according to the manner of Wittgenstein.[41]

Naturalism and its problems

The thesis of physicalism is that the mind is part of the material (or physical) world. Such a position faces the fundamental problem that the mind has certain properties that no material thing possesses. Physicalism must therefore explain how it is possible that these properties can emerge from a material thing nevertheless. The project of providing such an explanation is often referred to as the "naturalization of the mental."[28] What are the crucial problems that this project must attempt to resolve? The most well-known are probably the following two:[28]

Qualia

Many mental states have the property of being experienced subjectively in different ways by different individuals.[20] For example, it is obviously characteristic of the mental state of pain that it hurts. Moreover, your sensation of pain may not be identical to mine, since we have no way of measuring how much something hurts nor of describing exactly how it feels to hurt. Where does such an experience (quale) come from? Nothing indicates that a neural or functional state can be accompanied by such a pain experience. Often the point is formulated as follows: the existence of cerebral events, in and of themselves, cannot explain why they are accompanied by these corresponding qualitative experiences. Why do many cerebral processes occur with an accompanying experiential aspect in consciousness? It seems impossible to explain.[19]

Yet it also seems to many that science will eventually have to explain such experiences.[28] This follows from the logic of reductive explanations. If I try to explain a phenomenon reductively (e.g., water), I also have to explain why the phenomenon has all of the properties that it has (e.g., fluidity, transparency).[28]In the case of mental states, this means that there needs to be an explanation of why they have the property of being experienced in a certain way.

The problem of explaining the introspective, first-person experiential aspects of mental states, and consciousness in general, in terms of third-person quantitative neuroscience is called the explanatory gap.[42] There are several different views of the nature of this gap among contemporary philosophers of mind. David Chalmers and the early Frank Jackson interpret the gap as ontological in nature; that is, they maintain that qualia can never be explained by science because physicalism is false. There are two separate categories involved and one cannot be reduced to the other.[43] An alternative view is taken by philosophers such as Thomas Nagel and Colin McGinn. According to them, the gap is epistemological in nature. For Nagel, science is not yet able to explain subjective experience because it has not yet arrived at the level or kind of knowledge that is required. We are not even able to formulate the problem coherently.[20] For McGinn, on other hand, the problem is one of permanent and inherent biological limitations. We are not able to resolve the explanatory gap because the realm of subjective experiences is cognitively closed to us in the same manner that quantum physics is cognitively closed to elephants.[44] Other philosophers liquidate the gap as purely a semantic problem.

Intentionality

Intentionality is the capacity of mental states to be directed towards (about) or be in relation with something in the external world.[16] This property of mental states entails that they have contents and semantic referents and can therefore be assigned truth values. When one tries to reduce these states to natural processes there arises a problem: natural processes are not true or false, they simply happen.[45] It would not make any sense to say that a natural process is true or false. But mental ideas or judgments are true or false, so how then can mental states (ideas or judgments) be natural processes? The possibility of assigning semantic value to ideas must mean that such ideas are about facts. Thus, for example, the idea that Herodotus was a historian refers to Herodotus and to the fact that he was an historian. If the fact is true, then the idea is true; otherwise, it is false. But where does this relation come from? In the brain, there are only electrochemical processes and these seem not to have anything to do with Herodotus.[15]

Philosophy of mind and science

Humans are corporeal beings and, as such, they are subject to examination and description by the natural sciences. Since mental processes are not independent of bodily processes, the descriptions that the natural sciences furnish of human beings play an important role in the philosophy of mind.[32] There are many scientific disciplines that study processes related to the mental. The list of such sciences includes: biology, computer science, cognitive science, cybernetics, linguistics, medicine, pharmacology, psychology, etc.[46]

Neurobiology

The theoretical background of biology, as is the case with modern natural sciences in general, is fundamentally materialistic. The objects of study are, in the first place, physical processes, which are considered to be the foundations of mental activity and behavior.[47] The increasing success of biology in the explanation of mental phenomena can be seen by the absence of any empirical refutation of its fundamental presupposition: "there can be no change in the mental states of a person without a change in brain states."[46]

Within the field of neurobiology, there are many subdisciplines which are concerned with the relations between mental and physical states and processes:[47] Sensory neurophysiology investigates the relation between the processes of perception and stimulation.[48] Cognitive neuroscience studies the correlations between mental processes and neural processes.[48] Neuropsychology describes the dependence of mental faculties on specific anatomical regions of the brain.[48] Lastly, evolutionary biology studies the origins and development of the human nervous system and, in as much as this is the basis of the mind, also describes the ontogenetic and phylogenetic development of mental phenomena beginning from their most primitive stages.[46]

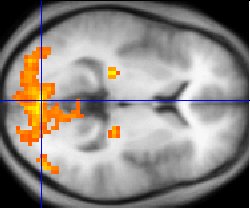

The methodological breakthroughs of the neurosciences, in particular the introduction of high-tech neuroimaging procedures, has propelled scientists toward the elaboration of increasingly ambitious research programs: one of the main goals is to describe and comprehend the neural processes which correspond to mental functions (see: neural correlate).[47] A very small number of neurobiologists, such as Emil du Bois-Reymond and John Carew Eccles have denied the possibility of a "reduction" of mental phenomena to cerebral processes, partly for religious reasons.[21] However, the contemporary neurobiologist and philosopher Gerhard Roth continues to defend a form of "non-reductive materialism."[49]

Computer science

Computer science concerns itself with the automatic processing of information (or at least with physical systems of symbols to which information is assigned) by means of such things as computers.[50] From the beginning, computer programmers have been able to develop programs which permit computers to carry out tasks for which organic beings need a mind. A simple example is multiplication. But it is clear that computers do not use a mind to multiply. Could they, someday, come to have what we call a mind? This question has been propelled into the forefront of much philosophical debate because of investigations in the field of artificial intelligence ("AI").

Within AI, it is common to distinguish between a modest research program and a more ambitious one: this distinction was coined by John Searle in terms of a weak AI and a strong AI. The exclusive objective of "weak AI", according to Searle, is the successful simulation of mental states, with no attempt to make computers become conscious or aware, etc. The objective of strong AI, on the contrary, is a computer with consciousness similar to that of human beings.[51] The program of strong AI goes back to one of the pioneers of computation Alan Turing. As an answer to the question "Can computers think?", he formulated the famous Turing test.[52] Turing believed that a computer could be said to "think" when, if placed in a room by itself next to another room which contained a human being and with the same questions being asked of both the computer and the human being by a third party human being, the computer's responses turned out to be indistinguishable from those of the human. Essentially, Turing's view of machine intelligence followed the behaviourist model of the mind - intelligence is as intelligence does. The Turing test has received many criticisms, among which the most famous is probably the Chinese room thought experiment formulated by Searle.[51]

The question about the possible sensitivity (qualia) of computers or robots still remains open. Some computer scientists believe that the specialty of AI can still make new contributions to the resolution of the "mind body problem". They suggest that based on the reciprocal influences between software and hardware that takes place in all computers, it is possible that someday theories can be discovered that help us to understand the reciprocal influences between the human mind and the brain (wetware).[53]

Psychology

Psychology is the science that investigates mental states directly. It uses generally empirical methods to investigate concrete mental states like joy, fear or obsessions. Psychology investigates the laws that bind these mental states to each other or with inputs and outputs to the human organism.[54]

An example of this is the psychology of perception. Scientists working in this field have discovered general principles of the perception of forms. A law of the psychology of forms says that objects that move in the same direction are perceived as related to each other.[46] This law describes a relation between visual input and mental perceptual states. However, it does not suggest anything about the nature of perceptual states. The laws discovered by psychology are compatible with all the answers to the mind-body problem already described.

Philosophy of mind in the continental tradition

Most of the discussion in this article has focused on the predominant school (or style) of philosophy in modern Western culture, usually called analytic philosophy (sometimes also inaccurately described as Anglo-American philosophy).[55] Other schools of thought exist, however, which are sometimes (also misleadingly) subsumed under the broad label of continental philosophy.[55] In any case, the various schools that fall under this label (phenomenology, existentialism, etc.) tend to differ from the analytic school in that they focus less on language and logical analysis and more on directly understanding human existence and experience. With reference specifically to the discussion of the mind, this tends to translate into attempts to grasp the concepts of thought and perceptual experience in some direct sense that does not involve the analysis of linguistic forms.[55]

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's Phenomenology of Mind, Hegel discusses three distinct types of mind: the subjective mind, the mind of an individual; the objective mind, the mind of society and of the State; and the Absolute mind, a unity of all concepts. See also Hegel's Philosophy of Mind from his Encyclopedia.[56]

In modern times, the two main schools that have developed in response or opposition to this Hegelian tradition are Phenomenology and Existentialism. Phenomenology, founded by Edmund Husserl, focuses on the contents of the human mind (see noema) and how phenomenological processes shape our experiences.[57] Existentialism, a school of thought founded upon the work of Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, focuses on the content of experiences and how the mind deals with such experiences.[58]

An important, though not very well known, example of a philosopher of mind and cognitive scientist who tries to synthesize ideas from both traditions is Ron McClamrock. Borrowing from Herbert Simon and also influenced by the ideas of existential phenomenologists such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Martin Heidegger, McClamrock suggests that man's condition of being-in-the-world ("Dasein", "In-der-welt-sein") makes it impossible for him to understand himself by abstracting away from it and examining it as if it were a detached experimental object of which he himself is not an integral part.[59]

Consequences of philosophy of mind

There are countless subjects that are affected by the ideas developed in the philosophy of mind. Clear examples of this are the nature of death and its definitive character, the nature of emotion, of perception and of memory. Questions about what a person is and what his or her identity consists of also have much to do with the philosophy of mind. There are two subjects that, in connection with the philosophy of the mind, have aroused special attention: free will and the self.[32]

Free will

In the context of the philosophy of mind, the question about the freedom of the will takes on a renewed intensity. This is certainly the case, at least, for materialistic determinists.[32] According to this position, natural laws completely determine the course of the material world. Mental states, and therefore the will as well, would be material states which means human behavior and decisions would be completely determined by natural laws. Some take this argumentation a step further: people cannot determine by themselves what they want and what they do. Consequently, they are not free.[60]

This argumentation is rejected, on the one hand, by the compatibilists. Those who adopt this position suggest that the question "Are we free?" can only be answered once we have determined what the term "free" means. The opposite of "free" is not "caused" but "compelled" or "coerced". It is not appropriate to identify freedom with indetermination. A free act is one where the agent could have done otherwise if it had chosen otherwise. In this sense a person can be free even though determinism is true.[60] The most important compatibilist in the history of the philosophy was David Hume.[61]Nowadays, this position is defended, for example, by Daniel Dennett,[62] and, from a dual-aspect perspective, by Max Velmans.[63]

On the other hand, there are also many incompatibilists who reject the argument because they believe that the will is free in a stronger sense called originationism.[60] These philosophers affirm that the course of the world is not completely determined by natural laws: the will at least does not have to be and, therefore, it is potentially free. The most prominent incompatibilist in the history of philosophy was Immanuel Kant.[64] Critics of this position accuse the incompatibilists of using an incoherent concept of freedom. They argue as follows: if our will is not determined by anything, then we desire what we desire by pure chance. And if what we desire is purely accidental, we are not free. So if our will is not determined by anything, we are not free.[60]

The self

The philosophy of mind also has important consequences for the concept of self. If by "self" or "I" one refers to an essential, immutable nucleus of the person, most modern philosophers of mind will affirm that no such thing exists.[65] The idea of a self as an immutable essential nucleus derives from the Christian idea of an immaterial soul. Such an idea is unacceptable to most contemporary philosophers, due to their physicalistic orientations, and due to a general acceptance among philosophers of the scepticism of the concept of 'self' by David Hume, who could never catch himself doing, thinking or feeling anything.[66] However, in the light of empirical results from developmental psychology, developmental biology and the neurosciences, the idea of an essential inconstant, material nucleus - an integrated representational system distributed over changing patterns of synaptic connections - seems reasonable.[67]

In view of this problem, some philosophers affirm that we should abandon the idea of a self.[65] For example, Thomas Metzinger and Susan Blackmore both practice meditation, claiming that this gives us reliable conscious experience of selflessness.[68] Philosophers and scientists holding this view frequently talk of the self, "I", agency and related concepts as 'illusory', a view with parallels in some Eastern religious traditions, such as anatta in Buddhism.[69] But this is a minority position. More common is the view that we should redefine the concept: by "self" we would not be referring to some immutable and essential nucleus, but to something that is in permanent change. A contemporary defender of this position is Daniel Dennett.[65]

See also

- For more information and links about topics discussed in the article, see: Portal:Mind and Brain

- For more information about scientific research related to topics discussed in the article, see: Cognitive science

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Plato (1995). in E.A. Duke, W.F. Hicken, W.S.M. Nicoll, D.B. Robinson, J.C.G. Strachan: Phaedo. Clarendon Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Robinson, H. (1983): ‘Aristotelian dualism’, Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy 1, 123-44.

- ↑ Nussbaum, M. C. (1984): ‘Aristotelian dualism’, Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, 2, 197-207.

- ↑ Nussbaum, M. C. and Rorty, A. O. (1992): Essays on Aristotle's De Anima, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sri Swami Sivananda. Sankhya:Hindu philosophy: The Sankhya.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Descartes, René. Discourse on Method and Meditations on First Philosophy. Hacket Publishing Company. ISBN 0-87220-421-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hart, W.D. (1996) "Dualism", in Samuel Guttenplan (org) A Companion to the Philosophy of Mind, Blackwell, Oxford, 265-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Spinoza, Baruch (1670) Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (A Theologico-Political Treatise).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Kim, J., "Mind-Body Problem", Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Ted Honderich (ed.). Oxford:Oxford University Press. 1995.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Churchland, Patricia (1986). Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain.. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03116-7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Churchland, Paul (1981). Eliminative Materialism and the Propositional Attitudes. Journal of Philosophy: 67-90.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Smart, J.J.C. (1956). Sensations and Brain Processes. Philosophical Review.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Donald Davidson (1980). Essays on Actions and Events. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924627-0.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 Putnam, Hilary (1967). "Psychological Predicates", in W. H. Capitan and D. D. Merrill, eds., Art, Mind and Religion (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dennett, Daniel (1998). The intentional stance. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54053-3.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Searle, John (2001). Intentionality. A Paper on the Philosophy of Mind. Frankfurt a. M.: Nachdr. Suhrkamp. ISBN 3-518-28556-4.

- ↑ Chalmers, D. (1996) The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Unger, P. (2006) All the Power in the World. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Jackson, F. (1982) “Epiphenomenal Qualia.” Reprinted in Chalmers, David ed. :2002. Philosophy of Mind: Classical and Contemporary Readings. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Nagel, T. (1974.). What is it like to be a bat?. Philosophical Review (83): 435-456.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Popper, Karl and Eccles, John (2002). The Self and Its Brain. Springer Verlag. ISBN 3-492-21096-1.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Robinson, Howard (2003-08-19). Dualism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2003 Edition). Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ Leibniz, Gottfried Wilhelm [1714]. Monadology.

- ↑ Schmaltz, Tad (2002). Nicolas Malebranche. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2002 Edition). Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Retrieved 2006-09-25.

- ↑ Hodgson, S. ((1865) Time and Space

- ↑ Jackson, Frank (1986,). What Mary didn't know. Journal of Philosophy.: 291-295.

- ↑ Chalmers, David (1997). The Conscious Mind. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511789-1.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 28.7 28.8 Stoljar, Daniel (2005). Physicalism. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 Edition). Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford University. Retrieved 2006-09-24.

- ↑ Mach, E. (1886) Die Analyse der Empfindungen und das Verhältnis des Physischen zum Psychischen. Fifth edition translated as The Analysis of Sensations and the Relation of Physical to the Psychical, New York: Dover. 1959

- ↑ Skinner,B.F. (1972). Beyond Freedom & Dignity. New York: Bantam/Vintage Books.

- ↑ Ryle, Gilbert (1949). The Concept of Mind. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 0-226-73295-9.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKim1 - ↑ Smart, J.J.C, "Identity Theory", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2002 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL=<http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2002/entries/malebranche/>

- ↑ Davidson, D. (2001). Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 88-7078-832-6.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Block, Ned. "What is functionalism" in Readings in Philosophy of Psychology, 2 vols. Vol 1. (Cambridge: Harvard, 1980).

- ↑ Armstrong, D., 1968, A Materialist Theory of the Mind, Routledge.

- ↑ ArmstrongNussbaum, M. C. & Putnam, H. (1992). Changing Aristotle's mind. In Nussbaum, M. C. & Rorty, A. O. (Eds.), Essays on Aristotle's De anima (pp. 27-56). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Stanton, W.L. (1983) "Supervenience and Psychological Law in Anomalous Monism", Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 64: 72-9

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Hacker, Peter (2003). Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience. Blackwel Pub.. ISBN 1-4051-0838-X.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Wittgenstein, Ludwig (1954). Philosophical Investigations. New York: Macmillan.

- ↑ Putnam, Hilary (2000). The Threefold Cord: Mind, Body, and World. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10286-0.

- ↑ Joseph Levine, Materialism and Qualia: The Explanatory Gap, in: Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 4, October, 1983, 354 - 361

- ↑ Jackson, F. (1986) "What Mary didn't Know", Journal of Philosophy, 83, 5, pp. 291-295.

- ↑ McGinn, C. "Can the Mind-Body Problem Be Solved", Mind, New Series, Volume 98, Issue 391, pp. 349-366. a[(online)]

- ↑ Fodor,Jerry (1993). Psychosemantics. The problem of meaning in the philosophy of mind. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06106-6.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Pinker, S. (1997) How the Mind Works. tr. It: Come Funziona la Mente. Milan:Mondadori, 2000. ISBN 88-04-49908-7

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Bear, M. F. et. al. Eds. (1995). Neuroscience: Exploring The Brain. Baltimore, Maryland, Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-3944-6

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Pinel, J.P.J (1997). Psychobiology. Prentice Hall. ISBN 88-15-07174-1.

- ↑ Roth, Gerhard (2001). The brain and its reality. Cognitive Neurobiology and its philosophical consequences. Frankfurt a.M.: Aufl. Suhrkamp. ISBN 3-518-58183-X.

- ↑ Sipser, M.. Introduction to the Theory of Computation. Boston, Mass.: PWS Publishing Co.. ISBN 0-534-94728-X.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Searle, John (1980). Minds, Brains and Programs. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences: 417-424.

- ↑ Turing, Alan (1950). Computing machinery and intelligence.

- ↑ Russell, S. and Norvig, R. (1995). Artificial Intelligence:A Modern Approach. New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc.. ISBN 0-13-103805-2.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Psychology.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Dummett, M. (2001). Origini della Filosofia Analitica. Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-15286-6.

- ↑ Hegel,G.W.F. Phenomenology of Spirit. , translated by A.V. Miller with analysis of the text and foreword by J. N. Findlay (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977) ISBN 0-19-824597-1 .

- ↑ Husserl,Edmund. Logische Untersuchungen. trans.: Giovanni Piana. Milan: EST. ISBN 88-428-0949-7

- ↑ Flynn, Thomas, "Jean-Paul Sartre", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2004 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ↑ McClamrock, Ron (1995). Existential Cognition: Computational Minds in the World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 Philosopher Ted Honderich's Determinism web resource.

- ↑ Russell, Paul, Freedom and Moral Sentiment: Hume's Way of Naturalizing Responsibility Oxford University Press: New York & Oxford, 1995.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (1984). The Varieties of Free Will Worth Wanting. Cambridge MA: Bradford Books-MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-54042-8.

- ↑ Velmans, Max (2003). How could conscious experiences affect brains?. Exeter: Imprint Academic. ISBN 0907845-39-8.

- ↑ Kant, Immanuel (1781). Critique of Pure Reason. translation: F. Max Muller, Dolphin Books, Doubleday & Co. Garden City, New York. 1961.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Dennett, C. and Hofstadter, D.R. (1981). The Mind's I. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-01412-9.

- ↑ Searle, John (Jan 2005). Mind: A Brief Introduction. Oxford University Press Inc, USA. ISBN 0-19-515733-8.

- ↑ LeDoux,Joseph (2002). The Synaptic Self. New York: Viking Penguin. ISBN 88-7078-795-8.

- ↑ Blackmore, Susan (Nov 2005). Conversations on Consciousness: Interviews with Twenty Minds. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280622-X.

- ↑ Lopez Jr., Donald S. (1995). Buddhism in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04441-4.

Further reading

- Rousseau, George S. (2004). Nervous Acts: Essays on Literature, Culture and Sensibility. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire (NY): Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3454-1.

- Sternberg, Eliezer J. (2007). Are You a Machine?: The Brain, the Mind, And What It Means to Be Human. Humanity Books. ISBN 1-59102-483-8.

External links

- Guide to Philosophy of Mind, compiled by David Chalmers.

- Contemporary Philosophy of Mind: An Annotated Bibliography, compiled by David Chalmers.

- Dictionary of Philosophy of Mind, edited by Chris Eliasmith.

- An Introduction to the Philosophy of Mind, by Paul Newall, aimed at beginners.

- A list of online papers on consciousness and philosophy of mind, compiled by David Chalmers

- Field guide to the Philosophy of Mind

ar:فلسفة العقل de:Philosophie des Geistes et:Vaimufilosoofia es:Filosofía de la mente fa:فلسفه ذهن fr:Philosophie de l'esprit is:Hugspeki it:Filosofia della mente he:הבעיה הפסיכופיזית nl:filosofie van geest en cognitie ja:心身問題の哲学 pl:Filozofia umysłu pt:Filosofia da mente ro:Filozofia minţii ru:Философия сознания sr:Филозофија ума fi:Mielenfilosofia zh:精神哲学

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.