Difference between revisions of "Patriarchy" - New World Encyclopedia

Lauren Davis (talk | contribs) (→Catholicism: moved "eastern orthodoxy") |

Lauren Davis (talk | contribs) (→In religion: ranked religions in order of size (descending)) |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

==In religion== | ==In religion== | ||

| − | === | + | ===Christianity=== |

| + | {{main|Christianity}} | ||

| − | + | In 1 Timothy 2:8-15, Paul outlines the role of women in the church, which includes dressing modestly and learning "in silence with all subjection" - not "to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man." In chapter 3, he delineates the roles and values of bishops and deacons, further discussing the supportive nature of their wives. | |

| − | + | ==== Catholicism ==== | |

| + | '''The Sacrament of Order''' is that which integrates men (and in some jurisdictions, also women) into the '''[[Holy Orders]]''' of bishops, priests (presbyters), and deacons, the threefold order of "administrators of the mysteries of God" (1 Corinthians 4:1), giving the person the mission to teach, sanctify, and govern, the three functions referred to in [[Latin (language)|Latin]] as the "tria munera". Only a bishop may administer this sacrament, as only a bishop holds the fullness of the Apostolic Ministry. Ordination as a bishop makes one a member of the body that has succeeded to that of the Apostles. Ordination as a priest configures a person to Christ the Head of the Church and the one essential Priest, empowering that person, as the bishops' assistant and vicar, to preside at the celebration of divine worship, and in particular to confect the sacrament of the Eucharist, acting "in persona Christi" (in the person of Christ). Ordination as a deacon configures the person to Christ the Servant of All, placing the deacon at the service of the Church, especially in the fields of the ministry of the Word, service in divine worship, pastoral guidance and charity. | ||

| − | + | ====Eastern Orthodoxy==== | |

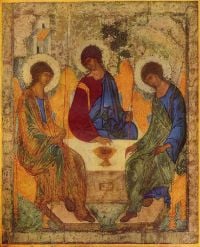

| − | + | [[Image:Andrej Rublëv 001.jpg|thumb|200px|right|The Holy Trinity/Hospitality of Abraham]] | |

| − | + | The Orthodox Church considers itself to be the original church started by Christ and his apostles. The life taught by Jesus to the apostles, invigorated by the [[Holy Spirit]] at [[Pentecost]], is known as ''Holy Tradition''. The [[Bible]], texts written by the apostles to record certain aspects of the life of the Church at the time, serves as the primary witness to Holy Tradition. Because of the Bible's apostolic origin, it is regarded as central to the life of the Church. | |

| − | [[ | + | Other witnesses to Holy Tradition include the liturgical services of the Church, its [[iconography]], the rulings of the [[Ecumenical council]]s, and the writings of the [[Church Fathers]]. From the consensus of the Fathers (''consensus patrum'') one may enter more deeply and understand more fully the Church's life. Individual Fathers are not looked upon as infallible, but, rather, the whole consensus of them together will give one a proper understanding of the Bible and Christian doctrine. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Eastern Orthodox]] churches follows a similar line of reasoning as the Roman Catholic Church with respect to ordination of priests. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Regarging deaconesses, Professor Evangelos Theodorou argued that female deacons were actually ordained in antiquity [http://www.stnina.org/journal/art/3.2.2]. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:<ref>"Man, Woman and the Priesthood of Christ", in ''Women and the Priesthood'', ed. T. Hopko (New York, 1982, reprinted 1999), 16, as quoted in ''Women Deacons in the Early Church'', by John Wijngaards, ISBN 0-8245-2393-8.</ref> | |

| + | <blockquote>The order of deaconesses seems definitely to have been considered an "ordained" ministry during early centures in at any rate the Christian East. [...] Some Orthodox writers regard deaconesses as having been a "lay" ministry. There are strong reasons for rejecting this view. In the Byzantine rite the liturgical office for the laying-on of hands for the deaconess is exactly parallel to that for the deacon; and so on the principle ''lex orandi, lex credendi'' — the Church's worshipping practice is a sure indication of its faith — it follows that the deaconesses receives, as does the deacon, a genuine sacramental ordination: not just a {{Polytonic|''χειροθεσια''}} but a {{Polytonic|''χειροτονια''}}.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | On [[October 8]], [[2004]], the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece voted [http://www.americamagazine.org/gettext.cfm?articleTypeID=1&textID=3997&issueID=517] to restore the female diaconate. | |

| − | + | There is a strong monastic tradition, pursued by both men and women in the Orthodox churches, where monks and nuns lead identical spiritual lives. Unlike Roman Catholic religious life, which has myriad traditions, both contemplative and active (see [[Benedictine monks]], [[Franciscan|Franciscan friars]], [[Jesuits]]), that of Eastern Orthodoxy has remained exclusively [[ascetic]] and [[monasticism|monastic]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Islam=== | |

| + | {{main|Islam}} | ||

| − | + | Although Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders, the [[imam]] serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. There is a current controversy among Muslims on the circumstances in which [[women]] may act as imams — that is, lead a congregation in [[salah|salat]] (prayer). Three of the four [[Sunni]] schools, as well as many [[Shia]], agree that a woman may lead a congregation consisting of women alone in prayer, although the [[Maliki]] school does not allow this. According to all currently existing traditional schools of [[Islam]], a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in [[salat]] (prayer). Some schools make exceptions for [[Tarawih]] (optional [[Ramadan]] prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars — including [[Al-Tabari]] (838–932), [[Abu Thawr]] (764–854), [[Al-Muzani]] (791–878), and [[Ibn Arabi]] (1165–1240) — considered the practice permissible at least for optional ([[nafila]]) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group. | |

| − | + | Some Muslims in recent years have reactivated the debate, arguing that the spirit of the [[Qur'an]] and the letter of a disputed [[hadith]] indicate that women should be able to lead mixed congregations as well as single-sex ones, and that the prohibition of this developed as a result of [[sexism]] in the medieval environment, not as a part of true Islam. | |

| − | |||

| − | ===== | + | ===Buddhism=== |

| − | |||

| − | + | The ordination of women is currently and historically practiced in some Buddhist regions, such East Asia and Taiwan, and not in others, such as [[India]] and [[Sri Lanka]]. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | The tradition of the ordained monastic community ([[sangha]]) began with [[Buddha]], who established orders of [[Bhikkhu]] (monks) and later, after an initial reluctance, of Bhikkuni (nuns). The stories, sayings and deeds of some of the distinguished Bhikkhuni of early Buddhism are recorded in many places in the [[Pali Canon]], most notably in the [[Therigatha]]. However, not only did the Buddha lay down more rules of discipline for the bhikkhuni (311 compared to the bhikkhu's 227), he also made it more difficult for them to be ordained. | |

| − | + | The tradition flourished for centuries throughout South and East Asia, but appears to have died out in the [[Theravada]] traditions of India and Sri Lanka in the [[11th century]] C.E. However, the [[Mahayana]] tradition, particularly in [[Taiwan]] and [[Hong Kong]], has retained the practice, where nuns are called 'Bhikṣuṇī' (the [[Sanskrit]] equivalent of the [[Pāli|Pali]] 'Bhikkhuni'). Nuns are also found in [[Korea]] and [[Vietnam]]. | |

| − | + | There have been some attempts in recent years to revive the tradition of women in the sangha within Theravada Buddhism in [[Thailand]], [[India]] and [[Sri Lanka]], with many women ordained in Sri Lanka since the late [[1990s]]. | |

| − | === | + | ===Judaism=== |

| − | + | {{main|Judaism}} | |

| − | + | While the patriarchs - Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob - formed what we know as Judaism, many considered the matriarchs - Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah - superior in prophesy.<ref>http://www.jewfaq.org/origins.htm The Patriarchs and the Origins of Judaism</ref> In ''Beyond Patriarchy: Jewish Fathers and Families'', Brandeis University professor Lawrence H. Fuchs discusses the modern role of fatherhood by outlining the evolution of the Jewish patriarchy. The first rabbis accorded women a relatively large amount of sexual and economic power in hopes of tempering the abuse of male power. Following this trajectory, fatherhood, religion, and dominance no longer have to be mutually inclusive. Fuchs goes as far to identify modern society as a post-patrarichy. | |

| − | + | Jewish tradition and law does not presume that women have more or less of an aptitude or moral standing required of [[rabbi]]s. However, it has been the longstanding practice that only men become rabbis. This practice continues to this day within the [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] and Hasidic communities but has been revised within non-Orthodox organizations. [[Reform Judaism]] created its first woman rabbi in [[1972]], [[Reconstructionist Judaism]] in [[1974]], and [[Conservative Judaism]] in [[1985]], and women in these movements are now routinely granted [[semicha]] on an equal basis with men. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | The issue of allowing women to become rabbis is not under active debate within the Orthodox community, though there is widespread agreement that women may often be consulted on matters of Jewish religious law. There are reports that a small number of Orthodox [[yeshiva]]s have unofficially granted semicha to women, but the prevailing consensus among Orthodox leaders (as well as a small number of Conservative Jewish communities) is that it is not appropriate for women to become rabbis. | ||

| + | The idea that women could eventually be ordained as rabbis sparks widespread opposition among the Orthodox rabbinate. Norman Lamm, one of the leaders of Modern Orthodoxy and Rosh Yeshiva of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological [[Seminary]], totally opposes giving semicha to women. "It shakes the boundaries of tradition, and I would never allow it." (Helmreich, 1997) Writing in an article in the ''Jewish Observer'', Moshe Y'chiail Friedman states that Orthodox Judaism prohibits women from being given semicha and serving as rabbis. He holds that the trend towards this goal is driven by [[sociology]], and not [[halakha]]. | ||

==In gender studies== | ==In gender studies== | ||

| Line 166: | Line 146: | ||

*[http://www.beliefnet.com/features/abrahamicfaiths.html The Abrahamic Faiths: A Comparison] How do Judaism, Christianity, and Islam differ? More from [[Beliefnet]] | *[http://www.beliefnet.com/features/abrahamicfaiths.html The Abrahamic Faiths: A Comparison] How do Judaism, Christianity, and Islam differ? More from [[Beliefnet]] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Credit7|Patriarchy|63289667|Chinese_patriarchy|52567812|Patrilineality|63499522|Patrilocal_residence|52584947|Paternalism|65153291|Eastern_Orthodox_Church|72268192|Ordination_of_women|74294140}} |

Revision as of 12:38, 7 September 2006

Patriarchy (from Greek: patria meaning father and arché meaning rule) is the anthropological term used to define the sociological condition where male members of a society tend to predominate in positions of power; the more powerful the position, the more likely it is that a male will hold that position. The term "patriarchy" is also used in systems of ranking male leadership in certain hierarchical churches or religious bodies (see patriarch and Patriarchate). Examples include the Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox churches. "Patriarchy" is also used pejoratively to describe a seemingly immobile and sclerotic political order.

Definition

The term "patriarchy" is distinct from patrilineality and patrilocality. "Patrilineal" defines societies where the derivation of inheritance (financial or otherwise) originates from the father's line; for example, a society with matrilineal traits such as Judaism provides that in order to be considered a Jew, a person must be born of a Jewish mother. "Patrilocal" defines a locus of control coming from the father's geographic/cultural community. In a matrilineal/matrilocal society, a woman lives with her mother and siblings, even after marriage; she does not leave her maternal home. Her brothers act as 'social fathers' and hold a higher influence on the woman's offspring to the detriment of the children's biological father. Most societies are predominantly patrilineal and patrilocal (see: matriarchy).

Patrilineality

Patrilineality (a.k.a agnatic kinship) is a system in which one belongs to one's father's lineage; it generally involves the inheritance of property, names, or titles through the male line.

A patriline is a line of descent from a male ancestor to a descendant (of either sex) in which the individuals in all intervening generations are male. In a patrilineal descent system (also called agnatic descent), an individual is considered to belong to the same descent group as his or her father. This directly contrasts the less common pattern of matrilineal descent.

The agnatic ancestry of an individual is his or her male ancestry. An agnate is one's (male) relative in an unbroken male line: a kinsman with whom one has a common ancestor by descent in an unbroken male line. The fact that the Y chromosome is paternally inherited enables geneticists to trace patrilines and agnatic kinships of men.

The Salic Law in medieval and later Europe purportedly served as the grounds for only males being eligible for hereditary succession to monarchies and fiefs, i.e in patrilineal or agnatic succession. The line of descent for monarchs and main personalities is almost exclusively through the main male personalities. (see Davidic line.)

Patrilocality

Patrilocality is a term used by social anthropologists to describe a socially instituted practice whereupon a married couple lives with or near the family of the husband.

A patrilocal residence is based on a rule that a man remains in his father's home after maturity. When he becomes married, his wife joins him in his father's home where the couple will raise their children. These children will follow the same pattern: Sons will stay, and daughters will move in with their husbands' families. Household sizes grow quickly as this process continues. Families living in a patrilocal residence generally assume joint ownership of domestic sources. A senior member leads the household and directs the labor of all other members.

Roughly 69% of the world's societies practice patrilocality.

Paternalism

Paternalism usually refers to an attitude or a policy stemming from the hierarchical pattern of a family based on patriarchy; a figurehead (the "father") makes decisions on behalf of others (the "children") for their own good, even if this is contrary to their opinions.

It is implied that the fatherly figure is wiser than and acts in the best interest of those he protects. The term is used derogatorily to characterize attitudes or political systems that are thought to deprive individuals of freedom - only nominally serving their interests while, in fact, pursuing another agenda.

In anthropology

Human societies - whether ancient, indigenous or modern industrial - have been described in anthropology as either patriarchal or matriarchal systems. Between these polarities lie a number of social structures which include elements of both systems (see above under Patriarchy a discussion of the terms patrilinial and patrilocal ).

Anthropologist Donald Brown has listed patriarchy as one of the "human universals" (Brown 1991, p. 137), which includes characteristics such as age gradation, personal hygiene, aesthetics, food sharing, and other sociological aspects, implying that patriarchy is innate to the human condition. Margaret Mead has observed that "... all the claims so glibly made about societies ruled by women are nonsense. We have no reason to believe that they ever existed....Men have always been the leaders in public affairs and the final authorities at home."[1]

Societies have developed out of patriarchal cultures. Institutions of religion, education, and commerce retain patriarchal practices. Patriarchy in the form of divided roles between women and men into domestic and social spheres is distinctly visible in modern Muslim countries. In Europe and America, whose cultures are based on a Christian model, political and religious power continues to exert a strong influence.

The ideas of Age of Enlightenment philosophy, and Revolutionary movements including Feminism have brought about changes creating wider possibilities for both women and men. Marxist ideals support the advocacy of egalitarianism between the sexes, but these aspirations have been overtaken by authoritarian forms of political organization in communist states. In China, for example, the law requires that an equal number of women and men compose the National People's Congress. There are, however, no women within the Politburo of the Communist Party of China, the agency that actually rules China. Prior to its dissolution, the Soviet Union's Congress of People's Deputies likewise consisted of equal numbers of men and women. Its successor, the Duma, which has governing authority, at present has only 35 female deputies among the 450 members.[2]

The longstanding thesis that societies are innately patriarchal has raised political opposition. The Modern Matriarchal Studies organization has held two conferences in Luxembourg (2004) and San Marcos, Texas (2005) in efforts to redefine the term "matriarchy." www.hagia.de/ (hagia being derived from the Greek hagios or "holy"}. Various chairs, called "priestesses" in the group's literature, conducted workshops and at the end of the conference declared that “International Matriarchal Politics stands against white supremacist patriarchal capitalist homogenization and the globalization of misery. It stands for egalitarianism, diversity and the economics of the heart. Many matriarchal societies still exist around the world and they propose an alternative, life affirming model to patriarchal raptor capitalism."Societies of Peace Declaration (2005), 2-3

Chinese Patriarchy

Chinese philosopher Mencius outlined the Three Subordinations: A woman was to be subordinate to her father in youth, her husband in maturity, and her son in old age.

Repeated throughout ancient Chinese tradition, the familiar notion that men govern the outer world, while women govern the home serves as a cliche of classical texts.

In the Han dynasty, the female historian Ban Zhao wrote the Lessons for Women to advise women how to behave. She outlined the Four Virtues women must abide by: proper virtue, proper speech, proper countenance, and proper merit. The "three subordinations and the four virtues" became a common four-character phrase throughout the imperial period.

As for the historical development of Chinese patriarchy, women's status was highest in the Tang dynasty, when women played sports (polo) and were generally freer in fashion and conduct. Between the Tang and Song dynasties, a fad for little feet arose, and from the Song dynasty forward footbinding became more and more common for the elite. In the Ming dynasty, a tradition of virtuous widowhood developed. Widows, even if widowed at a young age, were expected to not remarry. If they remained widows, their virtuous names might be displayed on the arch at the entrance of the village.

Examples of patriarchy in 20th and 21st century China include the immense pressure on women to get married before the age of 30 and the incidence of female infanticide associated with China's one child policy. However, footbinding has been eradicated and trafficking in women in China has greatly reduced.

In religion

Christianity

In 1 Timothy 2:8-15, Paul outlines the role of women in the church, which includes dressing modestly and learning "in silence with all subjection" - not "to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man." In chapter 3, he delineates the roles and values of bishops and deacons, further discussing the supportive nature of their wives.

Catholicism

The Sacrament of Order is that which integrates men (and in some jurisdictions, also women) into the Holy Orders of bishops, priests (presbyters), and deacons, the threefold order of "administrators of the mysteries of God" (1 Corinthians 4:1), giving the person the mission to teach, sanctify, and govern, the three functions referred to in Latin as the "tria munera". Only a bishop may administer this sacrament, as only a bishop holds the fullness of the Apostolic Ministry. Ordination as a bishop makes one a member of the body that has succeeded to that of the Apostles. Ordination as a priest configures a person to Christ the Head of the Church and the one essential Priest, empowering that person, as the bishops' assistant and vicar, to preside at the celebration of divine worship, and in particular to confect the sacrament of the Eucharist, acting "in persona Christi" (in the person of Christ). Ordination as a deacon configures the person to Christ the Servant of All, placing the deacon at the service of the Church, especially in the fields of the ministry of the Word, service in divine worship, pastoral guidance and charity.

Eastern Orthodoxy

The Orthodox Church considers itself to be the original church started by Christ and his apostles. The life taught by Jesus to the apostles, invigorated by the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, is known as Holy Tradition. The Bible, texts written by the apostles to record certain aspects of the life of the Church at the time, serves as the primary witness to Holy Tradition. Because of the Bible's apostolic origin, it is regarded as central to the life of the Church.

Other witnesses to Holy Tradition include the liturgical services of the Church, its iconography, the rulings of the Ecumenical councils, and the writings of the Church Fathers. From the consensus of the Fathers (consensus patrum) one may enter more deeply and understand more fully the Church's life. Individual Fathers are not looked upon as infallible, but, rather, the whole consensus of them together will give one a proper understanding of the Bible and Christian doctrine.

The Eastern Orthodox churches follows a similar line of reasoning as the Roman Catholic Church with respect to ordination of priests.

Regarging deaconesses, Professor Evangelos Theodorou argued that female deacons were actually ordained in antiquity [1]. Bishop Kallistos Ware wrote:[3]

The order of deaconesses seems definitely to have been considered an "ordained" ministry during early centures in at any rate the Christian East. [...] Some Orthodox writers regard deaconesses as having been a "lay" ministry. There are strong reasons for rejecting this view. In the Byzantine rite the liturgical office for the laying-on of hands for the deaconess is exactly parallel to that for the deacon; and so on the principle lex orandi, lex credendi — the Church's worshipping practice is a sure indication of its faith — it follows that the deaconesses receives, as does the deacon, a genuine sacramental ordination: not just a χειροθεσια but a χειροτονια.

On October 8, 2004, the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece voted [2] to restore the female diaconate.

There is a strong monastic tradition, pursued by both men and women in the Orthodox churches, where monks and nuns lead identical spiritual lives. Unlike Roman Catholic religious life, which has myriad traditions, both contemplative and active (see Benedictine monks, Franciscan friars, Jesuits), that of Eastern Orthodoxy has remained exclusively ascetic and monastic.

Islam

Although Muslims do not formally ordain religious leaders, the imam serves as a spiritual leader and religious authority. There is a current controversy among Muslims on the circumstances in which women may act as imams — that is, lead a congregation in salat (prayer). Three of the four Sunni schools, as well as many Shia, agree that a woman may lead a congregation consisting of women alone in prayer, although the Maliki school does not allow this. According to all currently existing traditional schools of Islam, a woman cannot lead a mixed gender congregation in salat (prayer). Some schools make exceptions for Tarawih (optional Ramadan prayers) or for a congregation consisting only of close relatives. Certain medieval scholars — including Al-Tabari (838–932), Abu Thawr (764–854), Al-Muzani (791–878), and Ibn Arabi (1165–1240) — considered the practice permissible at least for optional (nafila) prayers; however, their views are not accepted by any major surviving group.

Some Muslims in recent years have reactivated the debate, arguing that the spirit of the Qur'an and the letter of a disputed hadith indicate that women should be able to lead mixed congregations as well as single-sex ones, and that the prohibition of this developed as a result of sexism in the medieval environment, not as a part of true Islam.

Buddhism

The ordination of women is currently and historically practiced in some Buddhist regions, such East Asia and Taiwan, and not in others, such as India and Sri Lanka.

The tradition of the ordained monastic community (sangha) began with Buddha, who established orders of Bhikkhu (monks) and later, after an initial reluctance, of Bhikkuni (nuns). The stories, sayings and deeds of some of the distinguished Bhikkhuni of early Buddhism are recorded in many places in the Pali Canon, most notably in the Therigatha. However, not only did the Buddha lay down more rules of discipline for the bhikkhuni (311 compared to the bhikkhu's 227), he also made it more difficult for them to be ordained.

The tradition flourished for centuries throughout South and East Asia, but appears to have died out in the Theravada traditions of India and Sri Lanka in the 11th century C.E. However, the Mahayana tradition, particularly in Taiwan and Hong Kong, has retained the practice, where nuns are called 'Bhikṣuṇī' (the Sanskrit equivalent of the Pali 'Bhikkhuni'). Nuns are also found in Korea and Vietnam.

There have been some attempts in recent years to revive the tradition of women in the sangha within Theravada Buddhism in Thailand, India and Sri Lanka, with many women ordained in Sri Lanka since the late 1990s.

Judaism

While the patriarchs - Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob - formed what we know as Judaism, many considered the matriarchs - Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah - superior in prophesy.[4] In Beyond Patriarchy: Jewish Fathers and Families, Brandeis University professor Lawrence H. Fuchs discusses the modern role of fatherhood by outlining the evolution of the Jewish patriarchy. The first rabbis accorded women a relatively large amount of sexual and economic power in hopes of tempering the abuse of male power. Following this trajectory, fatherhood, religion, and dominance no longer have to be mutually inclusive. Fuchs goes as far to identify modern society as a post-patrarichy.

Jewish tradition and law does not presume that women have more or less of an aptitude or moral standing required of rabbis. However, it has been the longstanding practice that only men become rabbis. This practice continues to this day within the Orthodox and Hasidic communities but has been revised within non-Orthodox organizations. Reform Judaism created its first woman rabbi in 1972, Reconstructionist Judaism in 1974, and Conservative Judaism in 1985, and women in these movements are now routinely granted semicha on an equal basis with men.

The issue of allowing women to become rabbis is not under active debate within the Orthodox community, though there is widespread agreement that women may often be consulted on matters of Jewish religious law. There are reports that a small number of Orthodox yeshivas have unofficially granted semicha to women, but the prevailing consensus among Orthodox leaders (as well as a small number of Conservative Jewish communities) is that it is not appropriate for women to become rabbis.

The idea that women could eventually be ordained as rabbis sparks widespread opposition among the Orthodox rabbinate. Norman Lamm, one of the leaders of Modern Orthodoxy and Rosh Yeshiva of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, totally opposes giving semicha to women. "It shakes the boundaries of tradition, and I would never allow it." (Helmreich, 1997) Writing in an article in the Jewish Observer, Moshe Y'chiail Friedman states that Orthodox Judaism prohibits women from being given semicha and serving as rabbis. He holds that the trend towards this goal is driven by sociology, and not halakha.

In gender studies

In gender studies, the word patriarchy often refers to a social organization marked by the supremacy of a male figure, group of male figures, or men in general. It is depicted as subordinating women, children, and those whose genders or bodies defy traditional male/female categorization.

In such a context, qualifying something as "paternalistic" or "patriarchical" implies a pejorative meaning, having similar associations as "chauvinistic." However, a man or woman can behave in a paternalistic manner. For instance, many activists during the Women's Health Movement criticized doctors for their paternalistic actions. While most doctors were male, many female doctors encountered the same accusations because they also engaged in behavior that subordinated women.

Feminist view

Many feminist writers considered patriarchy the basis on which most modern societies have been formed. They argue that it is necessary and desirable to get away from this model in order to achieve gender equality.

Feminist writer Marilyn French, in her polemic Beyond Power, defines patriarchy as a system that values power over life, control over pleasure, and dominance over happiness. She argues that:

- It is therefore extremely ironic that patriarchy has upheld power as a good that is permanent and dependable, opposing it to the fluid, transitory goods of matricentry. Power has been exalted as the bulwark against pain, against the ephemerality of pleasure, but it is no bulwark, and is as ephemeral as any other part of life [...] Yet so strong is the mythology of power that we continue to believe, in the face of all evidence to the contrary, that it is substantial, that if we possessed enough of it we could be happy, that if some "great man" possessed enough of it, he could make the world come right.

According to French:

- It is not enough either to devise a morality that will allow the human race simply to survive. Survival is an evil when it entails existing in a state of wretchedness. Intrinsic to survival and continuation is felicity, pleasure [...] But pleasure does not exclude serious pursuits or intentions, indeed, it is found in them, and it is the only real reason for staying alive.[5]

The latter philosophy is what French offers as a replacement to the current structure where, she says, power has the highest value.

Gender-issues writer Cathy Young, by contrast, dismisses reference to "patriarchy" as a semantic device intended to shield the speaker from accountability when making misandrist slurs, since "patriarchy" means all of Western society.[6] She cites Andrea Dworkin's criticism, "Under patriarchy, every woman's son is her potential betrayer and also the inevitable rapist or exploiter of another woman."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Why Men Rule: A Theory of Male Dominance

- ↑ Women in Russian Politics

- ↑ "Man, Woman and the Priesthood of Christ", in Women and the Priesthood, ed. T. Hopko (New York, 1982, reprinted 1999), 16, as quoted in Women Deacons in the Early Church, by John Wijngaards, ISBN 0-8245-2393-8.

- ↑ http://www.jewfaq.org/origins.htm The Patriarchs and the Origins of Judaism

- ↑ Beyond Power: On Women, Men and Morals

- ↑ www.reason.com/cy/cy041905.shtml "Woman's Hating: The misdirected passion of Andrea Dworkin"

Bibliography

- Pierre Bourdieu, Masculine Domination, Polity Press 2001

- Robert Brown, Human Universals. Philadelphia: Temple University Press 1991

- Margaret Mead, Male and Female, London: Penguin 1950

- Maria Mies, Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour, Palgrave MacMillan 1999

- Sandra Morgen, Into Our Own Hands: The Women's Health Movement in the United States, 1969-1990, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press 2002

External links

- Cattle ownership makes it a man's world New Scientist (1. October 2003): Early matrilineal societies became patrilineal when they started herding cattle, a new study demonstrates

- Debate Between Mark Ridley and Stephen Goldberg on the Inevitability of Patriarchy

- The Return of Patriarchy by By Phillip Longman

- Chart and explanation of patrilocal residence

- What's Next? Heaven, hell, and salvation in major world religions A side-by-side comparison of different religion's views from Beliefnet.

- The Abrahamic Faiths: A Comparison How do Judaism, Christianity, and Islam differ? More from Beliefnet

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Patriarchy history

- Chinese_patriarchy history

- Patrilineality history

- Patrilocal_residence history

- Paternalism history

- Eastern_Orthodox_Church history

- Ordination_of_women history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.